Genome-Wide Characterization of the YTH Proteins in Salix suchowensis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials and Treatments

2.2. Identification of SsYTH Genes in S. suchowensis

2.3. Phylogenetic Analysis, Chromosome Mapping and Synteny Analysis

2.4. Gene Structure, Conserved Motifs and Conserved Domains Analysis

2.5. Identification of Prion Structural Sequence

2.6. Analysis of Cis-Regulatory Elements of SsYTH Gene Promoters

2.7. Total RNA Extraction and qRT-PCR Analysis of SsYTH Gene Expression

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

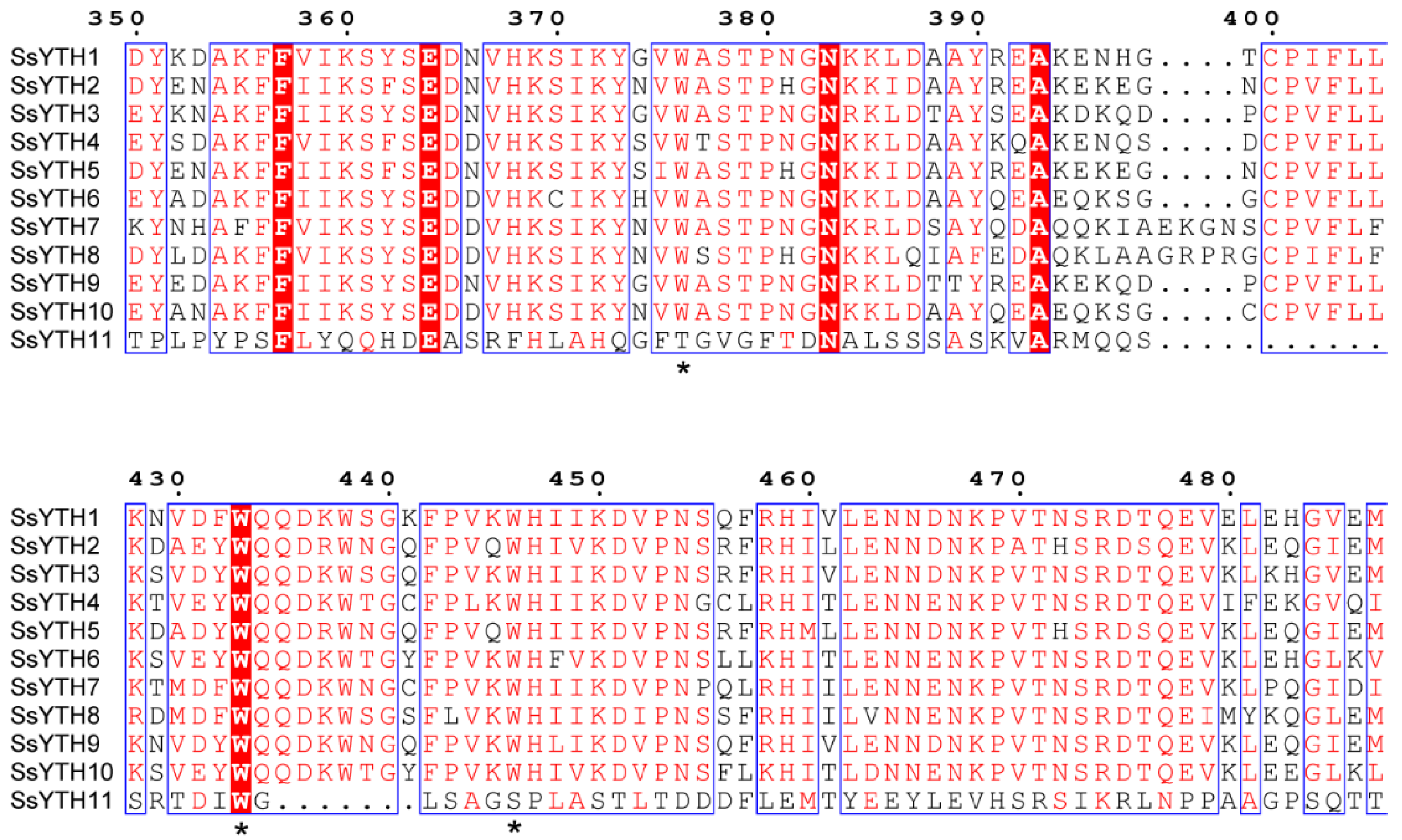

3.1. Genome-Wide Identification, Physicochemical Properties and Phylogenetic Analysis of SsYTH Proteins

3.2. Chromosome Localization of SsYTH Genes

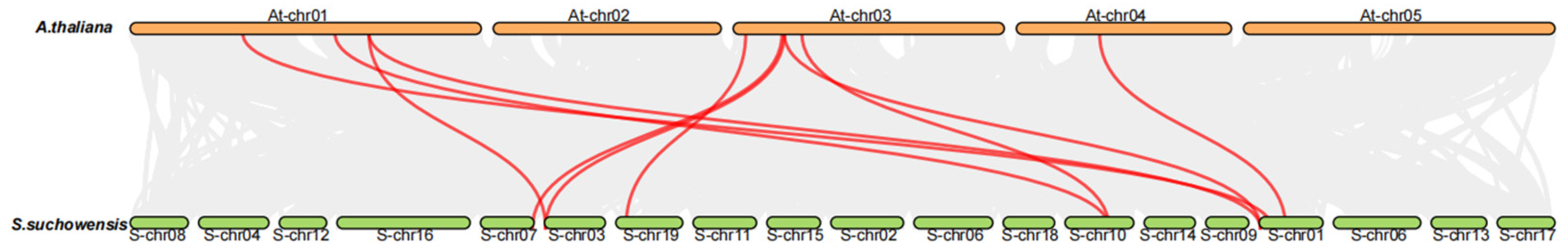

3.3. Collinearity Analysis of SsYTH Family

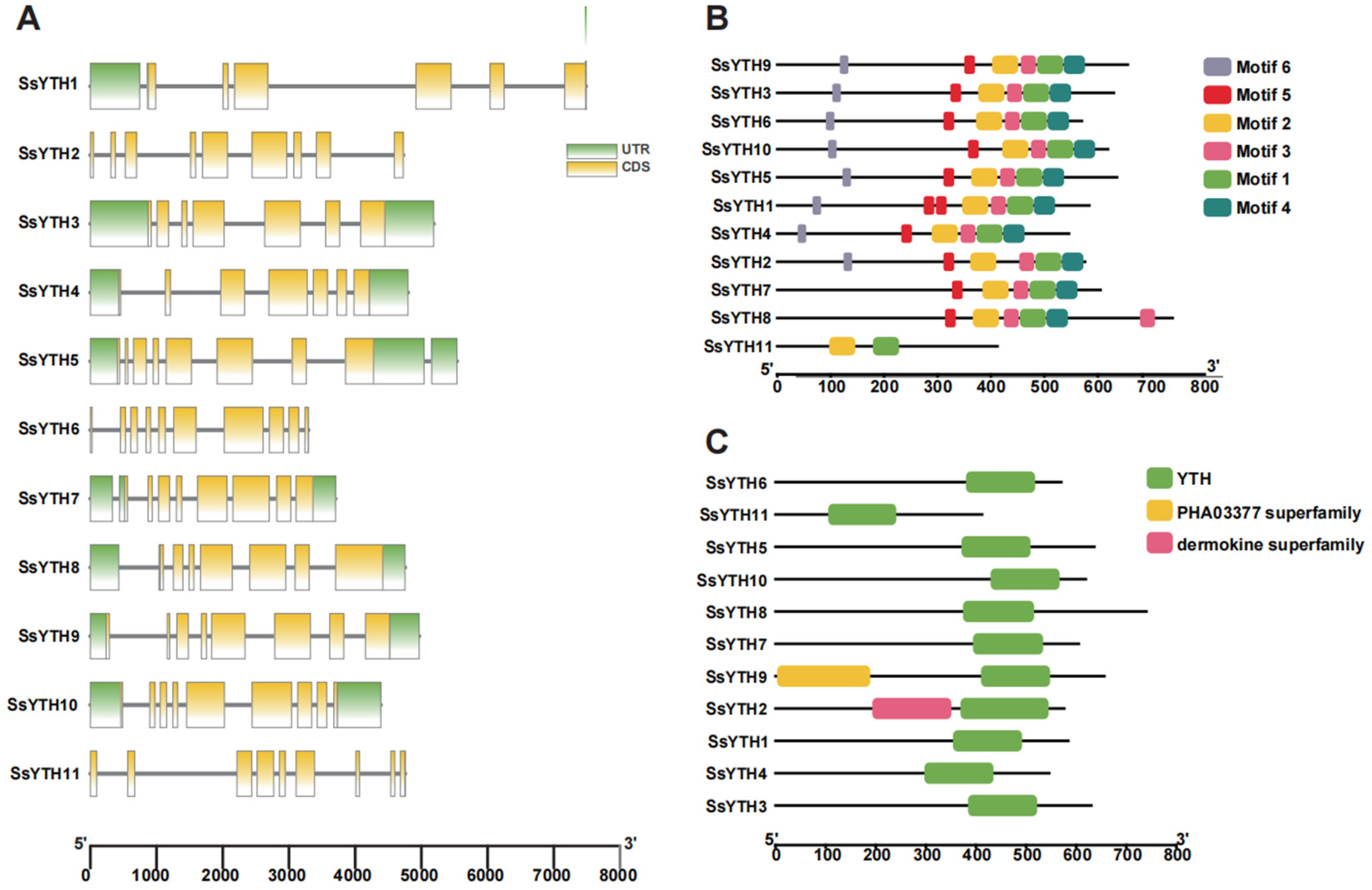

3.4. Gene Structure, Conserved Domain and Motif Analysis of SsYTH Genes

3.5. Prion-Like Domain Prediction and Phase Separation Potential

3.6. Tissue-Specific Expression Pattern of SsYTH Genes

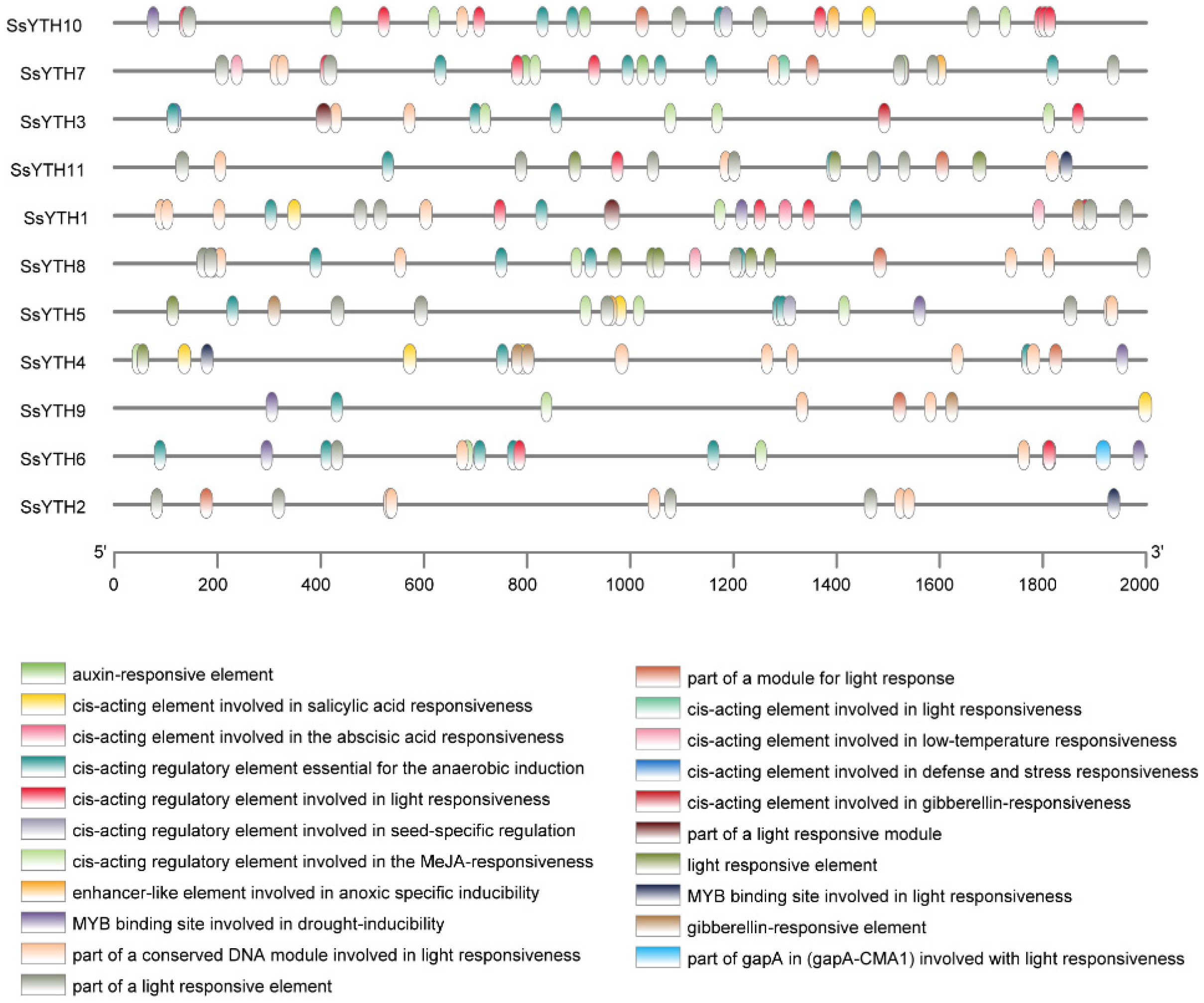

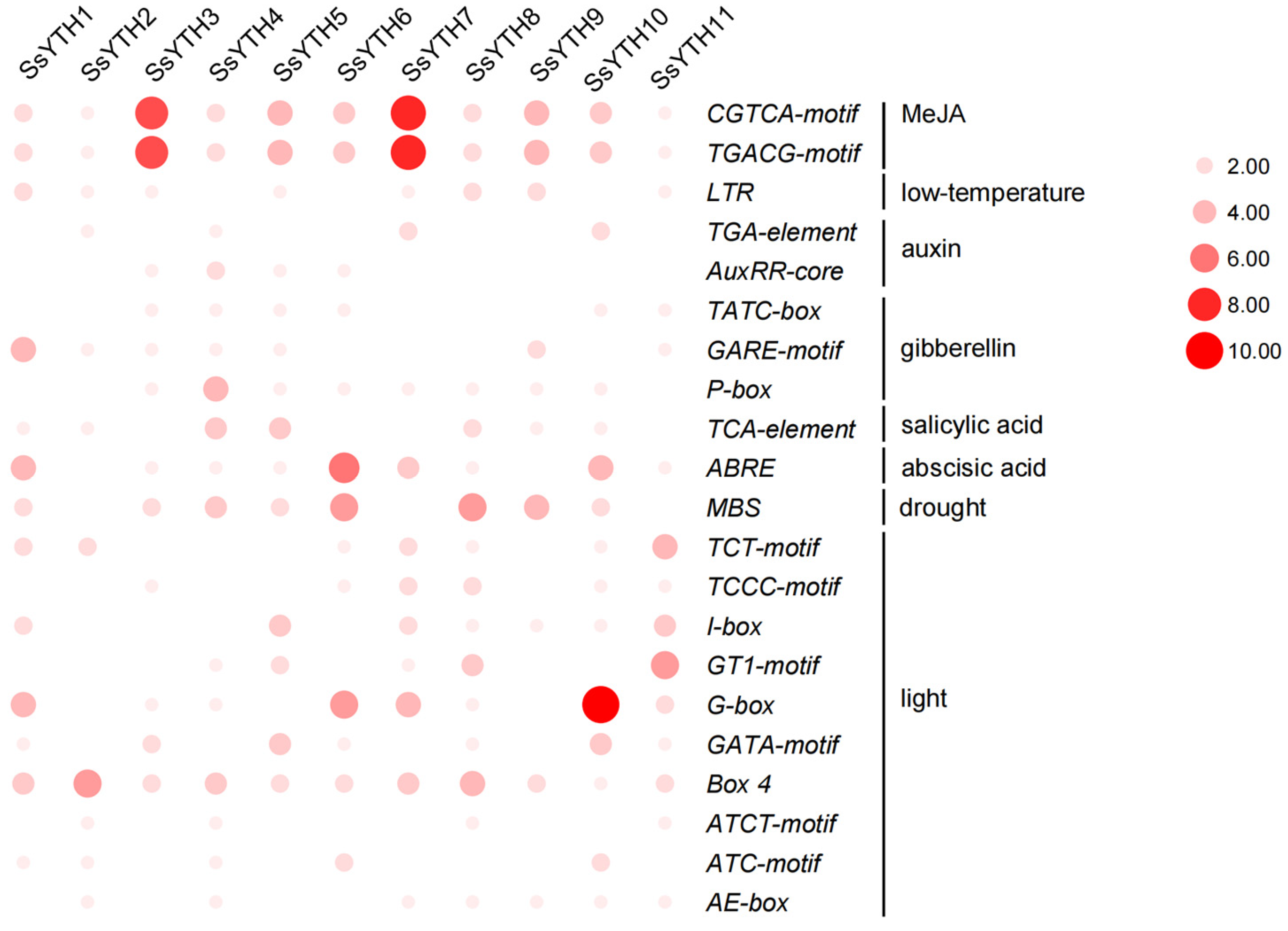

3.7. Analysis of Cis-Regulatory Elements in SsYTH Gene Promoter Region

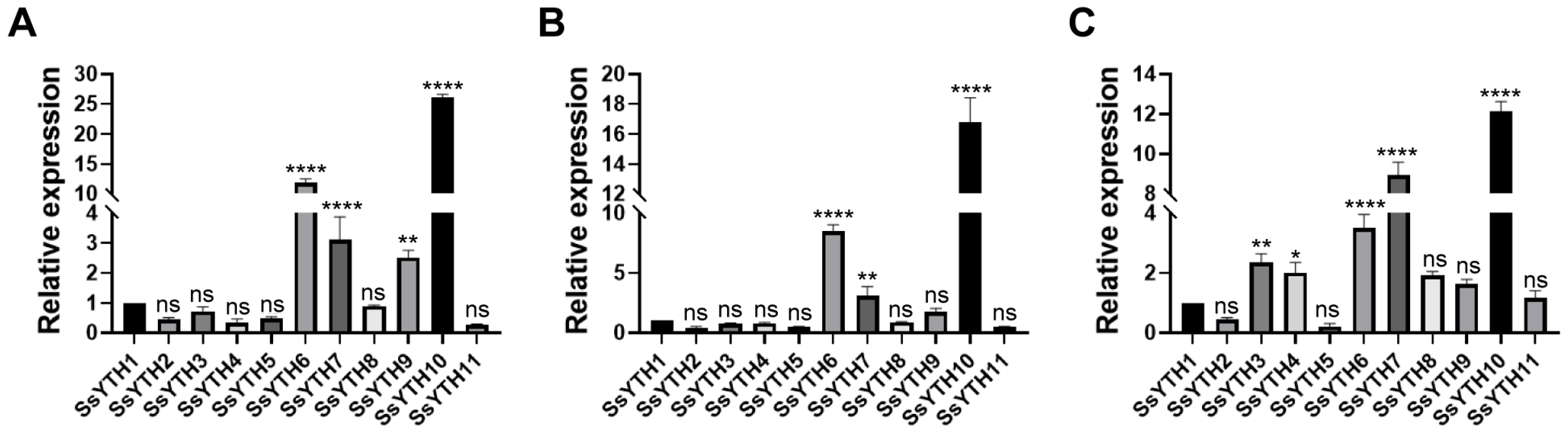

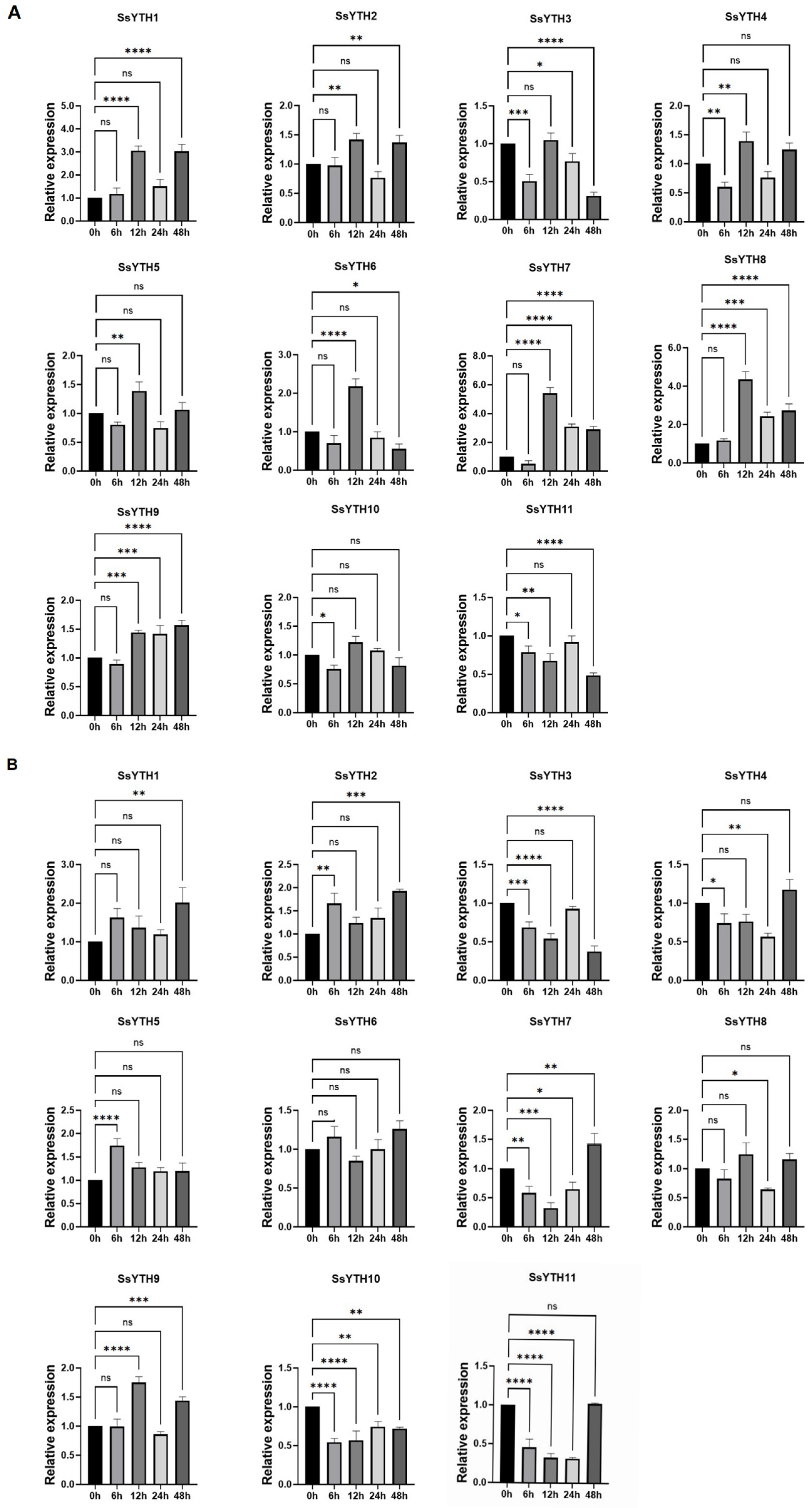

3.8. Expression Pattern of SSYTH Gene Under Hormone Treatment

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| qRT-PCR | Quantitative reverse transcription PCR |

| YTHDF | YTH domain family proteins |

| ECT | Evolutionarily conserved C-terminal |

| CPSF30 | Cleavage and Polyadenylation Specificity Factor 30 |

| CIPK1 | CBL-INTERACTING PROTEIN KINASE 1 |

| PrLDs | Prion-like domains |

| ANOVA | Analysis of variance |

References

- Boccaletto, P.; Stefaniak, F.; Ray, A.; Cappannini, A.; Mukherjee, S.; Purta, E.; Kurkowska, M.; Shirvanizadeh, N.; Destefanis, E.; Groza, P. MODOMICS: A database of RNA modification pathways. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, 231–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oerum, S.; Meynier, V.; Catala, M.; Tisné, C. A comprehensive review of m6A/m6Am RNA methyltransferase structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, 7239–7255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Hsu, P.J.; Chen, Y.; Yang, Y. Dynamic transcriptomic m6A decoration: Writers, erasers, readers and functions in RNA metabolism. Cell Res. 2018, 28, 616–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, B.; Li, L.; Huang, Y.; Ma, J.; Min, J. Readers, writers and erasers of N6-methylated adenosine modification. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2017, 47, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, S.; Sun, H.; Xu, C. YTH Domain: A Family of N6-methyladenosine (m6A) Readers. Genom. Proteom. Bioinform. 2018, 16, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Yin, P. Structural Insights into N6-methyladenosine (m6A) Modification in the Transcriptome. Genom. Proteom. Bioinform. 2018, 16, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, W.; Adhikari, S.; Dahal, U.; Chen, Y.; Hao, Y.; Sun, B.; Sun, H.; Li, A.; Ping, X.; Lai, W.; et al. Nuclear m6A Reader YTHDC1 Regulates mRNA Splicing. Mol. Cell 2016, 61, 507–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roundtree, I.A.; Luo, G.Z.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, X.; Zhou, T.; Cui, Y.; Sha, J.; Huang, X.; Guerrero, L.; Xie, P.; et al. YTHDC1 mediates nuclear export of N6-methyladenosine methylated mRNAs. eLife 2017, 6, e31311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; Zhao, Y.; He, J.; Zhang, Y.; Xi, H.; Liu, M.; Ma, J.; Wu, L. YTHDF2 destabilizes m(6)A-containing RNA through direct recruitment of the CCR4-NOT deadenylase complex. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 12626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arribas-Hernández, L.; Bressendorff, S.; Mathias, H.H.; Poulsen, C.; Erdmann, S.; Brodersen, P. An m6A-YTH Module Controls Developmental Timing and Morphogenesis in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2018, 30, 952–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, L.; Cui, S.; Jin, T.; Huang, X.; Hou, H.; Hao, B.; Xu, Z.; Cai, L.; Hu, Y.; Yang, X.; et al. The N6-methyladenosine binding proteins YTH03/05/10 coordinately regulate rice plant height. Plant Sci. 2023, 329, 111546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ao, Q.; Qiu, T.; Liao, F.; Hu, Z.; Yang, Y. Knockout of SlYTH2, encoding a YTH domain-containing protein, caused plant dwarfing, delayed fruit internal ripening, and increased seed abortion rate in tomato. Plant Sci. 2023, 335, 111807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, T.; Wang, N.; Xue, Y.; Guan, Q.; Steven, V.N.; Liu, C.; Ma, F. Overexpression of the RNA binding protein MhYTP1 in transgenic apple enhances drought tolerance and WUE by improving ABA level under drought condition. Plant Sci. 2019, 280, 397–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, L.; Song, P.; Wang, Y.; Lu, Z.; Tang, Q.; Yu, Q.; Xiao, Y.; Zhang, X.; Duan, H.; Jia, G. The m6A Reader ECT2 Controls Trichome Morphology by Affecting mRNA Stability in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2018, 30, 968–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arribas-Hernández, L.; Brodersen, P. Occurrence and Functions of m(6)A and Other Covalent Modifications in Plant mRNA. Plant Physiol. 2020, 182, 79–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ok, S.; Jeong, H.; Bae, J.; Shin, J.; Luan, S.; Kim, K. Novel CIPK1-associated proteins in Arabidopsis contain an evolutionarily conserved C-terminal region that mediates nuclear localization. Plant Physiol. 2005, 139, 138–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Sun, J.; Wu, B.; Gao, Y.; Nie, H.; Nie, Z.; Quan, S.; Wang, Y.; Cao, X.; Li, S. CPSF30-L-mediated recognition of mRNA m6A modification controls alternative polyadenylation of nitrate signaling-related gene transcripts in Arabidopsis. Mol. Plant 2021, 14, 688–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Cui, S.; Lu, Z.; Yan, X.; Cai, L.; Lu, Y.; Cai, K.; Zhou, H.; Ma, R.; Zhou, S.; et al. YTH Domain Proteins Play an Essential Role in Rice Growth and Stress Response. Plants 2022, 11, 2206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, S.; Ao, Q.; Qiu, T.; Tan, C.; Tu, Y.; Kuang, T.; Yang, Y. Tomato SlYTH1 encoding a putative RNA m6A reader affects plant growth and fruit shape. Plant Sci. 2022, 323, 111417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.; Tang, Y.; Li, S.; Zhang, L.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, R.; Diao, X.; Yu, J. The m6A reader SiYTH1 enhances drought tolerance by affecting the messenger RNA stability of genes related to stomatal closure and reactive oxygen species scavenging in Setaria italica. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2023, 65, 2569–2586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, J.; Chen, L.; Yan, X.; Yu, C.; Jiang, B. Genome-Wide Identification, Characterization, and Expression Analysis of VQ Gene Family in Salix suchowensis Under Abiotic Stresses and Hormone Treatments. Plants 2025, 14, 1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, P.; Li, Y. Prion–like Proteins in Plants: Key Regulators of Development and Environmental Adaptation via Phase Separation. Plants 2024, 13, 2666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, P.; Banjade, S.; Cheng, H.C.; Kim, S.; Chen, B.; Guo, L.; Llaguno, M.; Hollingsworth, J.V.; King, D.S.; Banani, S.F.; et al. Phase transitions in the assembly of multivalent signalling proteins. Nature 2012, 483, 336–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farag, M.; Borcherds, W.M.; Bremer, A.; Mittag, T.; Pappu, R.V. Phase separation of protein mixtures is driven by the interplay of homotypic and heterotypic interactions. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 5527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, Z.G.; Ang, W.S.L.; Poh, C.W.; Lai, S.K.; Sze, S.K.; Li, H.Y.; Bhushan, S.; Wunder, T.; Mueller-Cajar, O. A linker protein from a red–type pyrenoid phase separates with Rubisco via oligomerizing sticker motifs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2304833120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Zhuang, X. m6A-binding YTHDF proteins promote stress granule formation. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2020, 16, 955–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberti, S.; Gladfelter, A.; Mittag, T. Considerations and Challenges in Studying Liquid-Liquid Phase Separation and Biomolecular Condensates. Cell 2019, 176, 419–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banani, S.F.; Lee, H.O.; Hyman, A.A.; Rosen, M.K. Biomolecular condensates: Organizers of cellular biochemistry. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2017, 18, 285–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.; Lee, H.O.; Jawerth, L.; Maharana, S.; Jahnel, M.; Hein, M.Y.; Stoynov, S.; Mahamid, J.; Saha, S.; Franzmann, T.M.; et al. A Liquid-to-Solid Phase Transition of the ALS Protein FUS Accelerated by Disease Mutation. Cell 2015, 162, 1066–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, M.; Han, T.W.; Xie, S.; Shi, K.; Du, X.; Wu, L.C.; Mirzaei, H.; Goldsmith, E.J.; Longgood, J.; Pei, J.; et al. Cell-free Formation of RNA Granules: Low Complexity Sequence Domains Form Dynamic Fibers within Hydrogels. Cell 2012, 149, 753–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Kang, Y.; Li, S.; Yang, B.; Xia, X.; Wang, Z.; Qian, L.; Xiong, X.; Kang, L.; He, X. Identification and expression analysis of N6-methyltransferase and demethylase in rapeseed (Brassica napus L.). BMC Genom. 2025, 26, 526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, W.; Wang, W.; Xiao, X.; Sun, J.; Wu, B.; Zhao, Y.; Pei, S.; Fan, W.; Xu, D.; Qin, T. Genome-Wide Identification and Evolutionary Analysis of Gossypium YTH Domain-Containing RNA-Binding Protein Family and the Role of GhYTH8 in Response to Drought Stress. Plants 2023, 12, 1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yao, S.; Cheng, X.; Zhao, Y.; Yu, W.; Ren, X.; Ji, K.; Yu, Q. Genome-Wide Identification and Expression Analysis of the YTH Domain-Containing RNA-Binding Protein Family in Cinnamomum camphora. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 5960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Yao, S.; Zhang, J.; Wang, D.; Xu, S.; Yu, Q.; Ji, K. Genome-Wide Identification and Expression Analysis of YTH Gene Family for Abiotic Stress Regulation in Camellia chekiangoleosa. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 3996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Liu, F.; Wang, Y.; Chen, H.; Liu, T.; Li, M.; Chen, S.; Wang, D. Deciphering crucial salt-responsive genes in Brassica napus via statistical modeling and network analysis on dynamic transcriptomic data. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2025, 220, 109568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sequence ID | Gene ID | Number of Amino Acid | Molecular Weight (kDa) | Theoretical pI | Instability Index | Prediction of Subcellular Localization |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SsYTH1 | OIU78_009470 | 584 | 64.934 | 6.77 | 42.34 | nucleus |

| SsYTH2 | OIU78_003308 | 576 | 63.482 | 5.58 | 51.95 | nucleus |

| SsYTH3 | OIU78_016330 | 630 | 69.169 | 5.67 | 50.41 | nucleus |

| SsYTH4 | OIU78_022426 | 546 | 60.055 | 6.35 | 33.47 | cell wall or nucleus |

| SsYTH5 | OIU78_024349 | 636 | 69.788 | 5.11 | 49.42 | nucleus |

| SsYTH6 | OIU78_009064 | 570 | 63.608 | 7.59 | 30.39 | nucleus |

| SsYTH7 | OIU78_006626 | 605 | 66.605 | 6.73 | 45.94 | cell membrane or nucleus |

| SsYTH8 | OIU78_005119 | 740 | 81.547 | 6.57 | 36.93 | nucleus |

| SsYTH9 | OIU78_029138 | 656 | 72.136 | 5.43 | 52.43 | nucleus |

| SsYTH10 | OIU78_013017 | 619 | 68.799 | 6.45 | 36.66 | nucleus |

| SsYTH11 | OIU78_009943 | 412 | 46.27 | 7.69 | 48.09 | nucleus |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, Y.; Ma, Y.; Li, B.; Yin, H.; Guo, W.; Zhang, J.; Ji, K.; Yu, Q. Genome-Wide Characterization of the YTH Proteins in Salix suchowensis. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 1532. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121532

Chen Y, Ma Y, Li B, Yin H, Guo W, Zhang J, Ji K, Yu Q. Genome-Wide Characterization of the YTH Proteins in Salix suchowensis. Horticulturae. 2025; 11(12):1532. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121532

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Yu, Yuke Ma, Bao Li, Huijuan Yin, Wenhui Guo, Jingjing Zhang, Kongshu Ji, and Qiong Yu. 2025. "Genome-Wide Characterization of the YTH Proteins in Salix suchowensis" Horticulturae 11, no. 12: 1532. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121532

APA StyleChen, Y., Ma, Y., Li, B., Yin, H., Guo, W., Zhang, J., Ji, K., & Yu, Q. (2025). Genome-Wide Characterization of the YTH Proteins in Salix suchowensis. Horticulturae, 11(12), 1532. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121532