Phenotypic Diversity and Ornamental Evaluation Between Introduced and Domestically Bred Crabapple Germplasm

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Site Description

2.2. Plant Materials

2.3. Methods

2.3.1. Trait Selection and Measurement

2.3.2. Phenotypic Diversity and Homogeneity Analyses

2.3.3. Comprehensive Ornamental Value Evaluation

- (1)

- Hierarchical model construction: A three-level model was constructed, including goal layer (A, superior germplasm evaluation and selection), criteria layer (C, flower, foliar, fruit, and tree architectural traits), and alternatives layer (P, 15 specific traits, e.g., flower type, petal color outside, flower diameter, and exocarp color) (Figure 1).

- (2)

- Establishment of evaluation criteria: The assessment criteria were formulated based on pooled responses from expert consultations and structured questionnaires involving 20 breeders and 10 taxonomists. According to the ornamental value and scarcity [17], the related assessment traits were selected, and then graded on a five-point scale. A simple majority rule was applied to converge individual evaluations (Table S13).

- (3)

- Construction of judgment matrices: Five judgment matrices (A-C, C1-P, C2-P, C3-P, and C4-P) were constructed. The pairwise comparison judgment matrices were constructed using the 1–9 scale proposed by Saaty. The maximum eigenvalue (λmax) and weight coefficients (Wi) were calculated, followed by a consistency check (C.R. < 0.1).

- (4)

- Calculation of comprehensive score: The comprehensive score (Y) was calculated as:where Y is the score of the i-th indicator and Wi is the corresponding weight. The larger the Y value, the higher the ornamental value.Y = ∑(YiWi)

2.4. Data Processing

3. Results

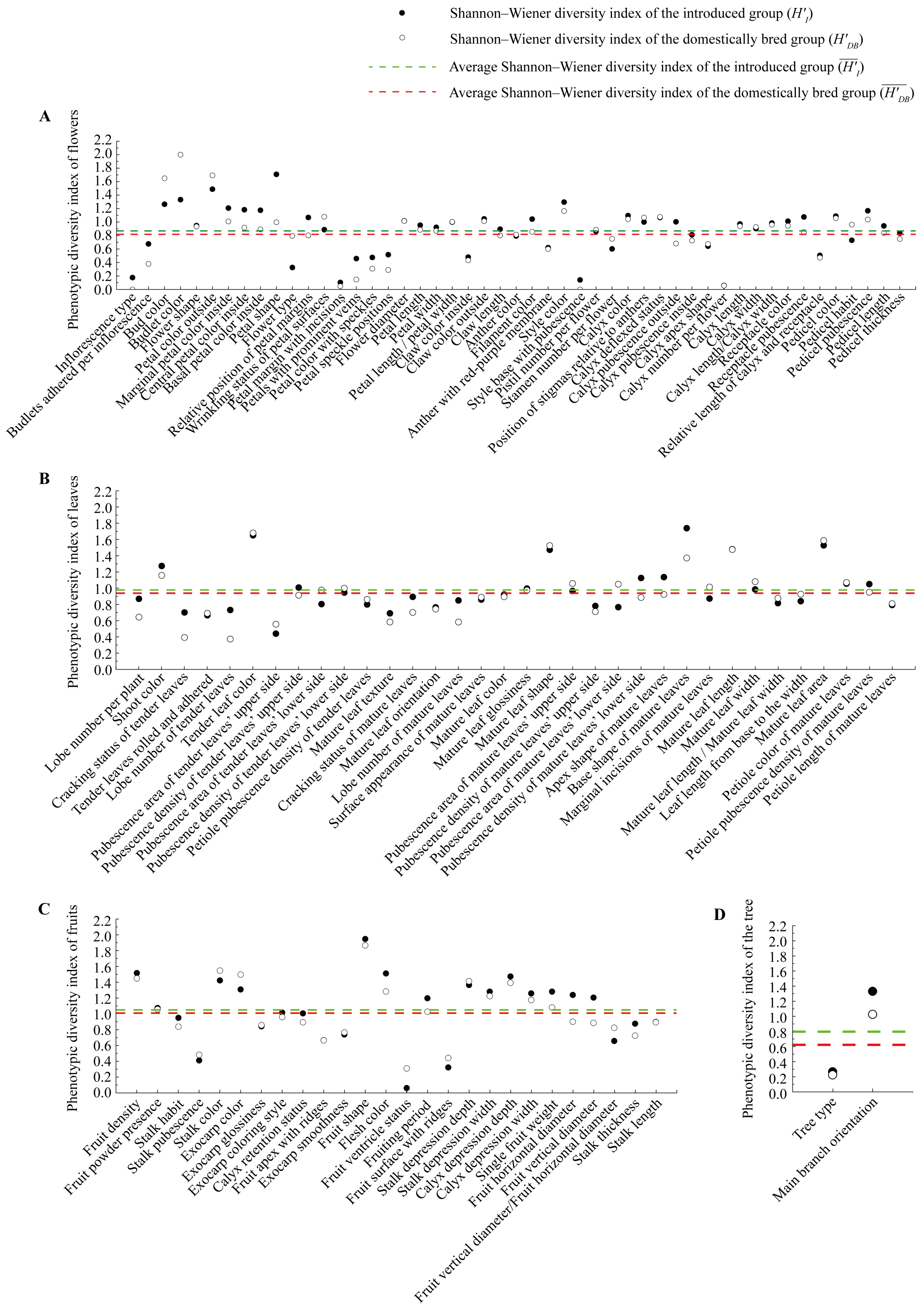

3.1. Phenotypic Diversity and Homogeneity in 211 Crabapple Cultivars/Lines

3.2. Phenotypic Diversity Comparison Between Different Crabapple Groups

3.3. Comprehensive Evaluation of Ornamental Characteristics for Crabapples

3.3.1. Consistency Check for Judgment Matrices

3.3.2. Weight Assignment Analysis for Indicators

3.3.3. Comprehensive Evaluation for Ornamental Crabapples

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications of Phenotypic Investigations for Revising Crabapple DUS Test Guideline

4.2. Exploration of Multiple Breeding Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Howard, E. Trees for American Gardens. Donald Wyman. Q. Rev. Biol. 1953, 28, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mratinić, E.; Akšić, M.F. Phenotypic diversity of apple (Malus sp.) germplasm in South Serbia. Braz. Arch. Biol. Technol. 2012, 55, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzher, B.M.; Younis, R.A.A.; El-Halabi, O.; Ismail, O.M. Genetic identification of some Syrian local apple (Malus sp.) cultivars using molecular markers. Res. J. Agric. Biol. Sci. 2007, 3, 704–713. [Google Scholar]

- Ulukan, H. The evolution of cultivated plant species: Classical plant breeding versus genetic engineering. Plant Syst. Evol. 2009, 280, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.K. Apple (Malus × Domestica); Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiala, J.L. Flowering Crabapples: The Genus Malus; Timber Press: Portland, OR, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Lobos, G.A.; Camargo, A.V.; Del Pozo, A.; Araus, J.L.; Ortiz, R.; Doonan, J.H. Editorial: Plant phenotyping and phenomics for plant breeding. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denaeghel, H.E.; Van Laere, K.; Leus, L.; Lootens, P.; Van Huylenbroeck, J.; Van Labeke, M.C. The variable effect of polyploidization on the phenotype in Escallonia. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, A.; Liebisch, F.; Hund, A. Plant phenotyping: From bean weighing to image analysis. Plant Methods 2015, 11, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhondt, S.; Wuyts, N.; Inzé, D. Cell to whole-plant phenotyping: The best is yet to come. Trends Plant Sci. 2013, 18, 428–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimoyama, N.; Johnson, M.; Beaumont, A.; Schlappi, M. Multiple cold tolerance trait phenotyping reveals shared quantitative trait loci in Oryza sativa. Rice 2020, 13, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Billot, C.; Ramu, P.; Bouchet, S.; Chantereau, J.; Deu, M.; Gardes, L.; Noyer, J.L.; Rami, J.F.; Rivallan, R.; Li, Y.; et al. Massive Sorghum collection genotyped with SSR markers to enhance use of global genetic resources. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e59714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, F.; Li, H.R.; Wang, J.Y.; Peng, H.X.; Chen, H.B.; Hu, F.C.; Lai, B.; Wei, Y.Z.; Ma, W.Q.; Li, H.L.; et al. Development of molecular markers based on the promoter difference of LcFT1 to discriminate easy- and difficult-flowering litchi germplasm resources and its application in crossbreeding. BMC Plant Biol. 2021, 21, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Q.; Zhao, S.; Guan, C.; Fu, G.; Yu, S.; Lin, S.; Wang, Z.; Fu, H.; Lu, X.; Cheng, S. Construction and evaluation of pepper core collection based on phenotypic traits and SSR markers. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 7473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höfer, M.; Eldin Ali, M.A.M.S.; Sellmann, J.; Peil, A. Phenotypic evaluation and characterization of a collection of Malus species. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2014, 61, 943–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.X.; Zhao, T.T.; Song, T.T.; Yao, Y.C.; Gao, J.P. Genetic diversity analysis in natural hybrid progeny of ornamental crabapple, Malus ‘Royalty’. Acta Hortic. Sin. 2011, 38, 2157–2168. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.X.; Fan, J.J.; Yang, P.; Zhou, T.; Pu, J.; Cao, F.L. Analysis of phenotypic characteristics of the Malus ‘Purple Prince’ half-sib progenies at the seedling stage. J. Nanjing For. Univ. Nat. Sci. Ed. 2017, 41, 33–40. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.F.; Zhang, W.X.; Zhu, L.L.; Jiang, H.; Sun, T.T.; Yu, W.W. Phenotypic diversity analysis of fruit traits of 78 north American crabapple cultivars. J. Nanjing For. Univ. Nat. Sci. Ed. 2025, 49, 165–173. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, T.; Fan, J.J.; Zhao, M.M.; Zhang, D.L.; Li, Q.H.; Wang, G.B.; Cao, F.L. Phenotypic variation of floral organs in Malus using frequency distribution functions. BMC Plant Biol. 2019, 19, 574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, T.; Ning, K.; Zhang, W.X.; Chen, H.; Lu, X.Q.; Zhang, D.L.; Yousry, A.E.K.; Bian, J. Phenotypic variation of floral organs in flowering crabapples and its taxonomic significance. BMC Plant Biol. 2021, 21, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, E.M. The flowering crabapple—A tree for all seasons. J. Arboric. 1981, 7, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.N.; Peng, J.; Wang, R.B.; Wang, H.W.; Li, Y.H.; Zhang, K.M. Phenotypic diversity analysis and comprehensive appreciation evaluation of 30 north American crabapples. Mol. Plant Breed. 2025, 23, 4440–4449. [Google Scholar]

- Azadeh, A.; Ghaderi, S.F.; Mirjalili, M.; Moghaddam, M. Integration of analytic hierarchy process and data envelopment analysis for assessment and optimization of personnel productivity in a large industrial bank. Expert Syst. Appl. 2011, 38, 5212–5225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semsri, A.; Suksukont, A. Sustainable energy conservation of reflow oven process on PCB manufacturing using AHP techniques. Int. J. Sustain. Energy 2024, 43, 2372567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seniv, M.M.; Kovtoniuk, A.M.; Yakovyna, V.S. Tools for selecting a software development methodology taking into account project characteristics. Radio Electron. Comput. 2022, 2, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.R. The Breeding and Cultivating of 33 Europe Malus Species or Cultivars and Their Ornamental Appraisal. Master’s Thesis, Nanjing Forestry University, Nanjing, China, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, X.; Feng, Y.; Chen, D.L.; Luo, C.; Yu, X.F.; Huang, C.L. Evaluation of Rosa germplasm resources and analysis of floral fragrance components in R. rugosa. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1026763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.L.; Wang, Y.W. The sustainable development research of wild plant tourism resources based on the entropy-AHP evaluation method. Adv. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 10, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, L.X.; Ni, Y.A.; Wang, J.W.; Chen, Y.; Gao, H.S. Characteristic-aroma-component-based evaluation and classification of strawberry varieties by aroma type. Molecules 2021, 26, 6219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- TG/192/1; Guidelines for the Conduct of Tests for Distinctness, Uniformity and Stability [Ornamental Apple (Malus Mill.)]. UPOV: Geneva, Switzerland, 2003.

- LY/T 3393-2024; Guidelines for the Conduct of Tests for Distinctness, Uniformity and Stability—Ornamental Apple (Malus Mill. except Malus domestica Borkh.). Code of China: Beijing, China, 2024.

- GB/T 19557.26-2022; Testing of New Varieties of Plants. Guidelines for the Conduct of Tests for Distinctness, Uniformity and Stability—Apple (Malus domestica Borkh.). Code of China: Beijing, China, 2022.

- Liu, Y.N. Studies of Standard Description and Database Construction of Malus Cultivars. Master’s Thesis, Beijing Forestry University, Beijing, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.J.; Wang, K.; Gao, Y.; Zhao, J.R.; Liu, L.J.; Gong, X.; Li, L.W. Preliminary investigation of modern distribution of Malus resources in China. J. Plant Genet. Resour. 2017, 18, 1116–1124. [Google Scholar]

- Fenster, C.B.; Cheely, G.; Dudash, M.R.; Reynolds, R.J. Nectar reward and advertisement in hummingbird-pollinated Silene virginica (Caryophyllaceae). Am. J. Bot. 2006, 93, 1800–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nattero, J.; Cocucci, A.A.; Medel, R. Pollinator-mediated selection in a specialized pollination system: Matches and mismatches across populations. J. Evolution. Biol. 2010, 23, 1957–1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.Q.; Tao, J. Recent advances on the development and regulation of flower color in ornamental plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.X.; Zhang, D.D.; Liu, D.; Li, F.L.; Lu, H. Exon skipping of AGAMOUS homolog PrseAG in developing double flowers of Prunus lannesiana (Rosaceae). Plant Cell Rep. 2013, 32, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noor, S.H.; Ushijima, K.; Murata, A.; Yoshida, K.; Tanabe, M.; Tanigawa, T.; Kubo, Y.; Nakano, R. Double flower formation induced by silencing of C-class MADS-box genes and its variation among petunia cultivars. Sci. Hortic. 2014, 178, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkio, M.; Jonas, U.; Declercq, M.; Nocker, S.V.; Knoche, M. Transcriptional dynamics of the developing sweet cherry (Prunus avium L.) fruit: Sequencing, annotation and expression profiling of exocarp-associated genes. Hortic. Res. 2014, 1, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majdi, C.; Pereira, C.; Dias, M.I.; Calhelha, R.C.; Alves, M.J.; Rhourri-Frih, B.; Charrouf, Z.; Barros, L.; Amaral, J.S.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R. Phytochemical characterization and bioactive properties of cinnamon basil (Ocimum basilicum cv. ‘Cinnamon’) and lemon basil (Ocimum × citriodorum). Antioxidants 2020, 9, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitzer-Rimon, B.; Duchin, S.; Bernstein, N.; Kamenetsky, R. Architecture and florogenesis in female Cannabis sativa plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.X.; Gao, J.; Wei, Y.L.; Ren, R.; Zhang, G.Q.; Lu, C.Q.; Jin, J.P.; Ai, Y.; Wang, Y.Q.; Chen, L.J.; et al. The genome of Cymbidium sinense revealed the evolution of orchid traits. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2021, 19, 2501–2516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Hierarchical Model | Judgment Matrix | Weight | Consistency Check | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A-C | A | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | λmax = 4.000 C.I. = 0.000 C.R. = 0.000 | ||

| C1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 0.3529 | |||

| C2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 0.3529 | |||

| C3 | 1/2 | 1/2 | 1 | 3/2 | 0.1764 | |||

| C4 | 1/3 | 1/3 | 2/3 | 1 | 0.1176 | |||

| C1-P1–4 | C1 | P1 | P2 | P3 | P4 | λmax = 4.006 C.I. = 0.002 C.R. = 0.002 | ||

| P1 | 1 | 1 | 5/4 | 5/3 | 0.2923 | |||

| P2 | 1 | 1 | 5/4 | 2 | 0.3064 | |||

| P3 | 4/5 | 4/5 | 1 | 5/4 | 0.2303 | |||

| P4 | 3/5 | 1/2 | 4/5 | 1 | 0.1707 | |||

| C2-P5–9 | C2 | P5 | P6 | P7 | P8 | P9 | λmax = 5.151 C.I. = 0.038 C.R. = 0.034 | |

| P5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 5/3 | 0.2674 | ||

| P6 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 5/3 | 0.2674 | ||

| P7 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 5/3 | 0.2674 | ||

| P8 | 1/6 | 1/6 | 1/6 | 1 | 6/5 | 0.0608 | ||

| P9 | 3/5 | 3/5 | 3/5 | 6/5 | 1 | 0.1367 | ||

| C3-P10–14 | C3 | P10 | P11 | P12 | P13 | P14 | λmax = 5.094 C.I. = 0.024 C.R. = 0.021 | |

| P10 | 1 | 2 | 5/4 | 5 | 2 | 0.3293 | ||

| P11 | 1/2 | 1 | 5/8 | 2 | 1 | 0.1584 | ||

| P12 | 4/5 | 8/5 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 0.2666 | ||

| P13 | 1/5 | 1/2 | 1/6 | 1 | 1/2 | 0.0686 | ||

| P14 | 1/2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0.1769 | ||

| C4-P15 | C4 | P15 | ||||||

| P15 | 1 | 0.1176 | ||||||

| Goal Layer (A) | Criteria Layer (C) | (A-Ci) Weight (Wi) | Alternatives Layer (P) | (C-Pi) Weight (Wi) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Selection of excellent cultivars/lines | Floral traits C1 | 0.3529 | Petal color outside P1 | 0.1031 |

| Flower density P2 | 0.1081 | |||

| Flower type P3 | 0.0813 | |||

| Flower diameter P4 | 0.0602 | |||

| Foliar traits C2 | 0.1764 | Tender leaf color P5 | 0.0581 | |

| Mature leaf color P6 | 0.0279 | |||

| Lobe number per plant P7 | 0.0470 | |||

| Mature leaf area P8 | 0.0121 | |||

| Mature leaf glossiness P9 | 0.0312 | |||

| Fruit traits C3 | 0.3529 | Exocarp color P10 | 0.0944 | |

| Fruiting period P11 | 0.0944 | |||

| Fruit density P12 | 0.0944 | |||

| Single fruit weight P13 | 0.0214 | |||

| Exocarp glossiness and smoothness P14 | 0.0482 | |||

| Tree architectural traits C4 | 0.1176 | Tree type P15 | 0.1176 |

| Grade | No. | Germplasm Name | Score | Flower | Fruit | Leaf | Tree Architecture |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | 1 | * M. ‘Indian Summer’ | 4.303 | 1.439 | 1.700 | 0.694 | 0.471 |

| I | 2 | * M. ‘Mary Potter’ | 4.168 | 1.400 | 1.679 | 0.619 | 0.471 |

| I | 3 | M. ‘Rainbow’ | 4.166 | 1.400 | 1.700 | 0.595 | 0.471 |

| I | 4 | * M. ‘Snowdrift’ | 4.133 | 1.400 | 1.679 | 0.584 | 0.471 |

| I | 5 | M. ‘Hong Ting’ | 4.121 | 1.400 | 1.700 | 0.550 | 0.471 |

| I | 6 | M. ‘Hong Baili’ | 4.118 | 1.482 | 1.652 | 0.514 | 0.471 |

| I | 7 | * M. ‘Royal Raindrop’ | 4.103 | 1.297 | 1.679 | 0.657 | 0.471 |

| I | 8 | * M. ‘Sweet SugartyMe’ | 4.091 | 1.400 | 1.679 | 0.541 | 0.471 |

| I | 9 | * M. ‘Red Jewel’ | 4.091 | 1.400 | 1.679 | 0.541 | 0.471 |

| I | 10 | M. ‘Zi Lian’ | 4.087 | 1.644 | 1.228 | 0.627 | 0.588 |

| I | 11 | M. ‘Xiang Yun’ | 4.085 | 1.704 | 1.323 | 0.587 | 0.471 |

| I | 12 | M. ‘Gou Huo’ | 4.074 | 1.421 | 1.584 | 0.598 | 0.471 |

| I | 13 | M. ‘Yuhua Shi’ | 4.073 | 1.460 | 1.511 | 0.514 | 0.588 |

| I | 14 | M. ‘Xia Wa’ | 4.069 | 1.482 | 1.558 | 0.560 | 0.471 |

| I | 15 | * M. ×zumi ‘Calocarpa’ | 4.062 | 1.340 | 1.679 | 0.573 | 0.471 |

| I | 16 | M. ‘Zise Xuanlv’ | 4.061 | 1.421 | 1.652 | 0.517 | 0.471 |

| I | 17 | * M. ‘Donald WyMan’ | 4.041 | 1.400 | 1.606 | 0.565 | 0.471 |

| I | 18 | M. ‘Luokeke Nvshi’ | 4.041 | 1.662 | 1.369 | 0.540 | 0.471 |

| I | 19 | M. ‘Melaleuca Bracteata’ | 4.031 | 1.340 | 1.679 | 0.542 | 0.471 |

| I | 20 | M. ‘Rui Qin’ | 4.030 | 1.541 | 1.490 | 0.528 | 0.471 |

| I | 21 | * M. ‘Tina’ | 4.028 | 1.280 | 1.679 | 0.599 | 0.471 |

| I | 22 | * M. ‘Golden Raindrop’ | 4.019 | 1.259 | 1.679 | 0.611 | 0.471 |

| I | 23 | * M. ‘Prairifire’ | 4.018 | 1.340 | 1.679 | 0.528 | 0.471 |

| I | 24 | M. ‘Hong Denglong’ | 4.006 | 1.259 | 1.700 | 0.577 | 0.471 |

| I | 25 | *M. ‘Fairytail Gold’ | 4.004 | 1.259 | 1.679 | 0.596 | 0.471 |

| I | 26 | M. ‘Chahua Nv’ | 4.002 | 1.704 | 1.369 | 0.458 | 0.471 |

| II | 1 | * M. ‘Winter Red’ | 3.993 | 1.400 | 1.627 | 0.494 | 0.471 |

| II | 2 | M. ‘Beiguo Zhichun’ | 3.988 | 1.541 | 1.463 | 0.514 | 0.471 |

| II | 3 | * M. ‘Molten Lava’ | 3.987 | 1.319 | 1.679 | 0.519 | 0.471 |

| II | 4 | M. ‘Er Qiao’ | 3.969 | 1.541 | 1.417 | 0.540 | 0.471 |

| II | 5 | * M. ‘Adirondack’ | 3.969 | 1.400 | 1.558 | 0.540 | 0.471 |

| II | 6 | * M. ‘Harvest Gold’ | 3.968 | 1.340 | 1.558 | 0.600 | 0.471 |

| II | 7 | * M. ‘Lancelot’ | 3.953 | 1.340 | 1.679 | 0.463 | 0.471 |

| II | 8 | * M. ‘King Arthur’ | 3.947 | 1.259 | 1.652 | 0.566 | 0.471 |

| II | 9 | * M. ‘Indian Magic’ | 3.937 | 1.482 | 1.396 | 0.590 | 0.471 |

| II | 10 | M. ‘Yangzhi Yu’ | 3.925 | 1.601 | 1.369 | 0.485 | 0.471 |

| II | 11 | * M. ‘Black Jade’ | 3.923 | 1.542 | 1.201 | 0.592 | 0.588 |

| II | 12 | M. ‘Chu Dong’ | 3.916 | 1.460 | 1.490 | 0.494 | 0.471 |

| II | 13 | * M. ‘Strawberry Jelly’ | 3.915 | 1.216 | 1.606 | 0.623 | 0.471 |

| II | 14 | M. ‘Hongse Yilian’ | 3.913 | 1.400 | 1.490 | 0.553 | 0.471 |

| II | 15 | M. ‘Hong Beile’ | 3.913 | 1.292 | 1.584 | 0.566 | 0.471 |

| II | 16 | M. ‘Red Coral’ | 3.912 | 1.211 | 1.679 | 0.552 | 0.471 |

| II | 17 | M. ‘Shanhu Hua’ | 3.907 | 1.482 | 1.396 | 0.560 | 0.471 |

| II | 18 | M. ‘Ying Hongxiu’ | 3.904 | 1.563 | 1.369 | 0.501 | 0.471 |

| II | 19 | * M. ‘Red Splendor’ | 3.903 | 1.378 | 1.511 | 0.543 | 0.471 |

| II | 20 | * M. ‘Cardinal’ | 3.901 | 1.297 | 1.606 | 0.528 | 0.471 |

| II | 21 | * M. ‘Cinderella’ | 3.901 | 1.259 | 1.631 | 0.542 | 0.471 |

| II | 22 | * M. ‘Red Baron’ | 3.889 | 1.352 | 1.511 | 0.555 | 0.471 |

| II | 23 | * M. ‘AdaM’ | 3.887 | 1.400 | 1.463 | 0.553 | 0.471 |

| II | 24 | * M. ‘Lisa’ | 3.885 | 1.482 | 1.417 | 0.516 | 0.471 |

| II | 25 | M. ‘Zi Dieer’ | 3.883 | 1.644 | 1.228 | 0.540 | 0.471 |

| II | 26 | * M. ‘Sugar TyMe’ | 3.873 | 1.319 | 1.558 | 0.526 | 0.471 |

| II | 27 | M. ‘Xingchen’ | 3.873 | 1.400 | 1.417 | 0.585 | 0.471 |

| II | 28 | M. ‘Lian Yi’ | 3.870 | 1.254 | 1.463 | 0.682 | 0.471 |

| II | 29 | * M. ‘Winter Gold’ | 3.869 | 1.319 | 1.536 | 0.544 | 0.471 |

| II | 30 | M. ‘Duo Jiao’ | 3.869 | 1.433 | 1.296 | 0.670 | 0.471 |

| II | 31 | M. ‘Feicui’ | 3.860 | 1.184 | 1.700 | 0.505 | 0.471 |

| II | 32 | M. ‘Hong Qingting’ | 3.855 | 1.184 | 1.604 | 0.597 | 0.471 |

| II | 33 | * M. ‘Rudolph’ | 3.853 | 1.297 | 1.511 | 0.574 | 0.471 |

| II | 34 | M. ‘Xiao Lian’ | 3.851 | 1.340 | 1.536 | 0.505 | 0.471 |

| II | 35 | M. ‘Jinxiang Yu’ | 3.850 | 1.340 | 1.558 | 0.482 | 0.471 |

| II | 36 | * M. ‘David’ | 3.849 | 1.400 | 1.511 | 0.467 | 0.471 |

| II | 37 | * M. ‘Professor Sprenger’ | 3.848 | 1.400 | 1.463 | 0.514 | 0.471 |

| II | 38 | M. ‘Zi Ju’ | 3.845 | 1.644 | 1.155 | 0.575 | 0.471 |

| II | 39 | M. ‘Hong Yunxuan’ | 3.841 | 1.340 | 1.442 | 0.589 | 0.471 |

| II | 40 | M. ‘Anni’ | 3.840 | 1.601 | 1.274 | 0.494 | 0.471 |

| II | 41 | M. ‘Fenhong Nichang’ | 3.838 | 1.541 | 1.323 | 0.504 | 0.471 |

| II | 42 | * M. ‘Show TiMe’ | 3.834 | 1.357 | 1.490 | 0.516 | 0.471 |

| II | 43 | M. ‘Chang Hong’ | 3.831 | 1.596 | 1.224 | 0.540 | 0.471 |

| II | 44 | *M. ‘Liset’ | 3.830 | 1.292 | 1.463 | 0.604 | 0.471 |

| II | 45 | M. ‘Xia He’ | 3.829 | 1.541 | 1.274 | 0.543 | 0.471 |

| II | 46 | M. ‘Hua Mulan’ | 3.827 | 1.340 | 1.442 | 0.575 | 0.471 |

| II | 47 | M. ‘Xiao Jiumei’ | 3.826 | 1.318 | 1.511 | 0.526 | 0.471 |

| II | 48 | M. ‘Qingyu An’ | 3.823 | 1.292 | 1.417 | 0.526 | 0.588 |

| II | 49 | * M. ‘Centurion’ | 3.821 | 1.330 | 1.511 | 0.509 | 0.471 |

| II | 50 | M. ‘Yellow Jade’ | 3.821 | 1.319 | 1.490 | 0.542 | 0.471 |

| II | 51 | M. ‘Haojue’ | 3.819 | 1.460 | 1.367 | 0.521 | 0.471 |

| II | 52 | M. ‘Yi Ren’ | 3.811 | 1.313 | 1.533 | 0.494 | 0.471 |

| II | 53 | * M. ‘Ballet’ | 3.810 | 1.493 | 1.274 | 0.572 | 0.471 |

| II | 54 | M. ‘Caoyuan Guniang’ | 3.810 | 1.297 | 1.463 | 0.579 | 0.471 |

| II | 55 | * M. ‘Robinson’ | 3.809 | 1.400 | 1.442 | 0.497 | 0.471 |

| II | 56 | M. ‘Leng Jing’ | 3.808 | 1.297 | 1.558 | 0.482 | 0.471 |

| II | 57 | M. ‘Zimei Hua’ | 3.805 | 1.340 | 1.442 | 0.553 | 0.471 |

| II | 58 | * M. ‘Van Eseltine’ | 3.802 | 1.493 | 1.369 | 0.470 | 0.471 |

| II | 59 | M. ‘Xiang Shanhu’ | 3.801 | 1.081 | 1.652 | 0.598 | 0.471 |

| II | 60 | * M. ‘Profusion’ | 3.799 | 1.373 | 1.369 | 0.586 | 0.471 |

| II | 61 | M. ‘Hong Zhuge’ | 3.797 | 1.292 | 1.536 | 0.498 | 0.471 |

| II | 62 | * M. ‘Gorgeous’ | 3.793 | 1.319 | 1.485 | 0.519 | 0.471 |

| II | 63 | * M. ‘Sparkler’ | 3.792 | 1.541 | 1.228 | 0.553 | 0.471 |

| II | 64 | * M. ‘Purple Prince’ | 3.779 | 1.340 | 1.323 | 0.646 | 0.471 |

| II | 65 | M. ‘Xin Tianyou’ | 3.772 | 1.400 | 1.301 | 0.482 | 0.588 |

| II | 66 | M. ‘Yun Xiangrong’ | 3.769 | 1.438 | 1.274 | 0.586 | 0.471 |

| II | 67 | M. ‘Hong Yun’ | 3.767 | 1.297 | 1.490 | 0.509 | 0.471 |

| II | 68 | * M. ‘Royal Beauty’ | 3.767 | 1.434 | 1.180 | 0.565 | 0.588 |

| II | 69 | * M. ‘Red Sentinel’ | 3.765 | 1.292 | 1.533 | 0.470 | 0.471 |

| II | 70 | M. ‘Zhu Rong’ | 3.764 | 1.563 | 1.199 | 0.532 | 0.471 |

| II | 71 | * M. ‘Sentinel’ | 3.764 | 1.194 | 1.606 | 0.494 | 0.471 |

| II | 72 | M. ‘Yanzhi Yu’ | 3.757 | 1.460 | 1.369 | 0.458 | 0.471 |

| II | 73 | M. ‘Dishui Guanyin’ | 3.757 | 1.227 | 1.533 | 0.526 | 0.471 |

| II | 74 | M. ‘Hu Po’ | 3.756 | 1.379 | 1.511 | 0.395 | 0.471 |

| II | 75 | * M. ‘Lollipop’ | 3.755 | 1.259 | 1.396 | 0.630 | 0.471 |

| III | 1 | M. ‘Gouqi Hong’ | 3.748 | 1.373 | 1.347 | 0.556 | 0.471 |

| III | 2 | M. ‘Yanzhi Zui’ | 3.744 | 1.340 | 1.461 | 0.472 | 0.471 |

| III | 3 | M. ‘Chang Hui’ | 3.744 | 1.536 | 1.228 | 0.509 | 0.471 |

| III | 4 | M. ‘Jinxiu Jiangnan’ | 3.744 | 1.439 | 1.301 | 0.533 | 0.471 |

| III | 5 | M. ‘Ruo Lian’ | 3.740 | 1.433 | 1.201 | 0.635 | 0.471 |

| III | 6 | M. ‘Xiaocun Zhilian’ | 3.740 | 1.378 | 1.417 | 0.474 | 0.471 |

| III | 7 | M. ‘Fen Balei’ | 3.739 | 1.553 | 1.201 | 0.514 | 0.471 |

| III | 8 | * M. ‘Radiant’ | 3.735 | 1.297 | 1.369 | 0.599 | 0.471 |

| III | 9 | M. ‘Hong Jun’ | 3.732 | 1.352 | 1.369 | 0.540 | 0.471 |

| III | 10 | M. ‘Yu Xiuqiu’ | 3.727 | 1.575 | 1.129 | 0.552 | 0.471 |

| III | 11 | M. ‘Orange DreaM’ | 3.723 | 1.292 | 1.396 | 0.565 | 0.471 |

| III | 12 | M. ‘Shu Hongzhuang’ | 3.722 | 1.340 | 1.396 | 0.516 | 0.471 |

| III | 13 | * M. ‘Roger’s Selection’ | 3.721 | 1.280 | 1.301 | 0.670 | 0.471 |

| III | 14 | * M. ‘Kelsey’ | 3.717 | 1.541 | 1.107 | 0.599 | 0.471 |

| III | 15 | M. ‘Ruo Ju’ | 3.714 | 1.325 | 1.296 | 0.623 | 0.471 |

| III | 16 | M. ‘Lvse Fengbao’ | 3.709 | 1.357 | 1.390 | 0.491 | 0.471 |

| III | 17 | *M. ‘Weeping Madonna’ | 3.708 | 1.434 | 1.180 | 0.624 | 0.471 |

| III | 18 | M. ‘Zi Lu’ | 3.705 | 1.108 | 1.511 | 0.498 | 0.588 |

| III | 19 | M. ‘Dafen Kongque’ | 3.705 | 1.216 | 1.536 | 0.482 | 0.471 |

| III | 20 | * M. ‘Golden Hornet’ | 3.700 | 1.113 | 1.579 | 0.538 | 0.471 |

| III | 21 | * M. ‘CandyMint’ | 3.690 | 1.237 | 1.396 | 0.587 | 0.471 |

| III | 22 | M. ‘Zi Ning’ | 3.689 | 1.292 | 1.417 | 0.509 | 0.471 |

| III | 23 | * M. ‘May’s Delight’ | 3.684 | 1.155 | 1.490 | 0.568 | 0.471 |

| III | 24 | M. ‘Pink Pillar’ | 3.678 | 1.378 | 1.301 | 0.528 | 0.471 |

| III | 25 | M. ‘Ziwei Xing’ | 3.676 | 1.237 | 1.463 | 0.506 | 0.471 |

| III | 26 | * M. ‘Red Jade’ | 3.676 | 1.211 | 1.417 | 0.460 | 0.588 |

| III | 27 | M. ‘Jin Sheng’ | 3.663 | 1.373 | 1.323 | 0.497 | 0.471 |

| III | 28 | M. ‘Zi Tang’ | 3.662 | 1.211 | 1.413 | 0.568 | 0.471 |

| III | 29 | M. ‘Meiren Xiao’ | 3.660 | 1.194 | 1.511 | 0.485 | 0.471 |

| III | 30 | M. ‘Lizi Haitang’ | 3.660 | 1.319 | 1.274 | 0.596 | 0.471 |

| III | 31 | M. ‘Fen Baihe’ | 3.657 | 1.400 | 1.267 | 0.519 | 0.471 |

| III | 32 | M. ‘Zuijin Xiang’ | 3.656 | 1.047 | 1.601 | 0.538 | 0.471 |

| III | 33 | * M. ‘Dolgo’ | 3.656 | 1.352 | 1.339 | 0.494 | 0.471 |

| III | 34 | M. ‘Yong Shi’ | 3.648 | 1.297 | 1.417 | 0.463 | 0.471 |

| III | 35 | * M. ‘Firebird’ | 3.642 | 1.259 | 1.396 | 0.517 | 0.471 |

| III | 36 | * M. ‘AlMey’ | 3.634 | 1.249 | 1.323 | 0.592 | 0.471 |

| III | 37 | M. ‘Jiu Er’ | 3.629 | 1.168 | 1.439 | 0.552 | 0.471 |

| III | 38 | M. ‘Chushui Furong’ | 3.629 | 1.167 | 1.463 | 0.528 | 0.471 |

| III | 39 | M. ‘Doukou Nianhua’ | 3.626 | 1.297 | 1.274 | 0.584 | 0.471 |

| III | 40 | M. ‘Haixing’ | 3.625 | 1.150 | 1.463 | 0.540 | 0.471 |

| III | 41 | M. ‘Zi Ting’ | 3.625 | 1.644 | 0.991 | 0.519 | 0.471 |

| III | 42 | M. ‘Xingxing Suo’ | 3.624 | 1.399 | 1.253 | 0.501 | 0.471 |

| III | 43 | * M. ‘Spring Glory’ | 3.624 | 1.249 | 1.250 | 0.654 | 0.471 |

| III | 44 | M. ‘Hong Ri’ | 3.620 | 1.211 | 1.417 | 0.521 | 0.471 |

| III | 45 | M. ‘Hudie Quan’ | 3.612 | 1.237 | 1.274 | 0.513 | 0.588 |

| III | 46 | M. ‘Da Hongying’ | 3.608 | 1.352 | 1.323 | 0.463 | 0.471 |

| III | 47 | M. ‘Lingbo Xianzi’ | 3.606 | 1.134 | 1.442 | 0.560 | 0.471 |

| III | 48 | M. ‘Li Hui’ | 3.604 | 1.373 | 1.267 | 0.493 | 0.471 |

| III | 49 | * M. ‘Brandywine’ | 3.602 | 1.433 | 1.100 | 0.599 | 0.471 |

| III | 50 | * M. ‘Everest’ | 3.595 | 1.400 | 1.151 | 0.573 | 0.471 |

| III | 51 | * M. ‘Guard’ | 3.589 | 1.400 | 1.224 | 0.494 | 0.471 |

| III | 52 | M. ‘Hong Chen’ | 3.582 | 1.297 | 1.274 | 0.540 | 0.471 |

| III | 53 | M. ‘Li Zan’ | 3.568 | 1.232 | 1.396 | 0.470 | 0.471 |

| III | 54 | * M. ‘Selkirk’ | 3.568 | 1.249 | 1.250 | 0.598 | 0.471 |

| III | 55 | M. ‘Yue Guang’ | 3.567 | 1.563 | 1.064 | 0.469 | 0.471 |

| III | 56 | M. ‘Wunv’ | 3.565 | 1.297 | 1.253 | 0.544 | 0.471 |

| III | 57 | M. ‘Tingshang Jiangyue’ | 3.559 | 1.390 | 1.180 | 0.519 | 0.471 |

| III | 58 | * M. ‘Spring Sensation’ | 3.558 | 1.259 | 1.301 | 0.528 | 0.471 |

| III | 59 | * M. ‘White Cascade’ | 3.557 | 1.340 | 1.159 | 0.470 | 0.588 |

| III | 60 | M. ‘Shen Ziwei’ | 3.553 | 1.292 | 1.274 | 0.516 | 0.471 |

| III | 61 | M. ‘Xiao Wei’ | 3.538 | 1.237 | 1.369 | 0.461 | 0.471 |

| III | 62 | M. ‘Xiao Qingxin’ | 3.531 | 1.248 | 1.228 | 0.584 | 0.471 |

| III | 63 | M. ‘Xiangfei’ | 3.528 | 1.194 | 1.369 | 0.494 | 0.471 |

| III | 64 | * M. ‘Abundance’ | 3.515 | 1.216 | 1.344 | 0.485 | 0.471 |

| III | 65 | M. ‘Mo Yu’ | 3.509 | 1.400 | 1.180 | 0.458 | 0.471 |

| III | 66 | M. ‘Kang Qiao’ | 3.499 | 0.999 | 1.511 | 0.519 | 0.471 |

| III | 67 | M. ‘Lianhua Xiu’ | 3.494 | 1.264 | 1.296 | 0.463 | 0.471 |

| III | 68 | M. ‘Zi Linglong’ | 3.477 | 1.318 | 1.159 | 0.529 | 0.471 |

| III | 69 | * M. ‘Shelley’ | 3.473 | 1.319 | 1.201 | 0.482 | 0.471 |

| III | 70 | * M. ‘Irene’ | 3.457 | 1.163 | 1.317 | 0.507 | 0.471 |

| III | 71 | * M. ‘Hopa’ | 3.457 | 1.276 | 1.201 | 0.509 | 0.471 |

| III | 72 | * M. ‘Pink Princess’ | 3.452 | 1.155 | 1.180 | 0.646 | 0.471 |

| III | 73 | * M. ‘Velvet Pillar’ | 3.450 | 1.184 | 1.323 | 0.472 | 0.471 |

| III | 74 | M. ‘Lei Xiu’ | 3.449 | 1.237 | 1.130 | 0.494 | 0.588 |

| III | 75 | * M. ‘Neville CopeMan’ | 3.446 | 1.237 | 1.242 | 0.497 | 0.471 |

| III | 76 | * M. ‘Butterball’ | 3.443 | 1.052 | 1.485 | 0.435 | 0.471 |

| III | 77 | * M. ‘KlehM’s IMproved Bechtel’ | 3.437 | 1.433 | 0.795 | 0.738 | 0.471 |

| III | 78 | M. ‘Dongfang Hong’ | 3.436 | 1.378 | 1.083 | 0.504 | 0.471 |

| III | 79 | M. ‘Bride’ | 3.411 | 1.004 | 1.490 | 0.446 | 0.471 |

| III | 80 | * M. ‘Eleyi’ | 3.409 | 1.189 | 1.296 | 0.453 | 0.471 |

| III | 81 | M. ‘Hong Yuhei’ | 3.405 | 1.400 | 1.018 | 0.516 | 0.471 |

| III | 82 | M. ‘Qianban Lian’ | 3.403 | 1.330 | 1.130 | 0.474 | 0.471 |

| III | 83 | * M. ‘MakaMik’ | 3.402 | 1.249 | 1.105 | 0.577 | 0.471 |

| IV | 1 | * M. ‘John Downie’ | 3.395 | 1.216 | 1.180 | 0.528 | 0.471 |

| IV | 2 | M. ‘Bai Lian’ | 3.392 | 1.330 | 1.086 | 0.507 | 0.471 |

| IV | 3 | M. ‘Lankou’ | 3.391 | 0.999 | 1.369 | 0.553 | 0.471 |

| IV | 4 | * M. ‘Louisa Contort’ | 3.386 | 1.004 | 1.253 | 0.540 | 0.588 |

| IV | 5 | * M. ‘Louisa’ | 3.384 | 1.113 | 1.159 | 0.525 | 0.588 |

| IV | 6 | * M. ×purpurea ‘LeMoinei’ | 3.376 | 1.244 | 1.130 | 0.532 | 0.471 |

| IV | 7 | M. ‘Lan Ting’ | 3.371 | 1.108 | 1.323 | 0.470 | 0.471 |

| IV | 8 | M. ‘Niu Dun’ | 3.351 | 1.243 | 1.104 | 0.533 | 0.471 |

| IV | 9 | M. ‘Xiao Chunfeng’ | 3.347 | 1.140 | 1.274 | 0.461 | 0.471 |

| IV | 10 | * M. ‘Regal’ | 3.346 | 1.146 | 1.223 | 0.507 | 0.471 |

| IV | 11 | * M. ‘Darwin’ | 3.346 | 1.189 | 1.201 | 0.485 | 0.471 |

| IV | 12 | * M. ‘Coralburst’ | 3.345 | 1.296 | 1.108 | 0.470 | 0.471 |

| IV | 13 | * M. ‘Ai Ruike ’ | 3.341 | 1.081 | 1.296 | 0.493 | 0.471 |

| IV | 14 | * M. ‘Pink Spires’ | 3.340 | 1.163 | 1.207 | 0.499 | 0.471 |

| IV | 15 | * M. ‘Perfect Purple’ | 3.333 | 1.189 | 1.134 | 0.540 | 0.471 |

| IV | 16 | * M. ‘Hillier’ | 3.331 | 1.237 | 1.064 | 0.442 | 0.588 |

| IV | 17 | M. ‘Jin Yu’ | 3.323 | 1.065 | 1.250 | 0.538 | 0.471 |

| IV | 18 | * M. ‘Show Girl’ | 3.317 | 1.124 | 1.228 | 0.494 | 0.471 |

| IV | 19 | M. ‘Mulan Xiu’ | 3.317 | 1.184 | 1.112 | 0.550 | 0.471 |

| IV | 20 | * M. ‘Red Great’ | 3.279 | 1.168 | 1.107 | 0.533 | 0.471 |

| IV | 21 | * M. ‘Royal GeM’ | 3.278 | 1.184 | 1.013 | 0.611 | 0.471 |

| IV | 22 | M. ‘Hong Manao’ | 3.257 | 1.042 | 1.274 | 0.470 | 0.471 |

| IV | 23 | * M. ‘Coccinella’ | 3.180 | 1.108 | 1.086 | 0.516 | 0.471 |

| IV | 24 | M. ‘Xiao Pingguo’ | 3.119 | 0.978 | 1.150 | 0.521 | 0.471 |

| IV | 25 | * M. ‘Royalty’ | 2.808 | 0.982 | 0.802 | 0.552 | 0.471 |

| IV | 26 | * M. ‘Praire Rose’ | 2.774 | 1.601 | 0.000 | 0.702 | 0.471 |

| IV | 27 | * M. ‘Spring Snow’ | 2.448 | 1.542 | 0.000 | 0.435 | 0.471 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ning, K.; Li, B.; Nie, H.; Liao, S.; Chen, X.; Yang, X.; Zhang, W.; El-Kassaby, Y.A.; Zhou, T. Phenotypic Diversity and Ornamental Evaluation Between Introduced and Domestically Bred Crabapple Germplasm. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 1527. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121527

Ning K, Li B, Nie H, Liao S, Chen X, Yang X, Zhang W, El-Kassaby YA, Zhou T. Phenotypic Diversity and Ornamental Evaluation Between Introduced and Domestically Bred Crabapple Germplasm. Horticulturae. 2025; 11(12):1527. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121527

Chicago/Turabian StyleNing, Kun, Bowen Li, Hongming Nie, Shuqi Liao, Xinrui Chen, Xiaoqian Yang, Wangxiang Zhang, Yousry A. El-Kassaby, and Ting Zhou. 2025. "Phenotypic Diversity and Ornamental Evaluation Between Introduced and Domestically Bred Crabapple Germplasm" Horticulturae 11, no. 12: 1527. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121527

APA StyleNing, K., Li, B., Nie, H., Liao, S., Chen, X., Yang, X., Zhang, W., El-Kassaby, Y. A., & Zhou, T. (2025). Phenotypic Diversity and Ornamental Evaluation Between Introduced and Domestically Bred Crabapple Germplasm. Horticulturae, 11(12), 1527. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121527