A Scheme for Speed Breeding of Tomato Through Modification of the Light Environment

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material and Growth Conditions

2.2. Growth and Morphology Assessment

2.3. Sampling and Germination Ability Test

2.4. Statistical Analysis

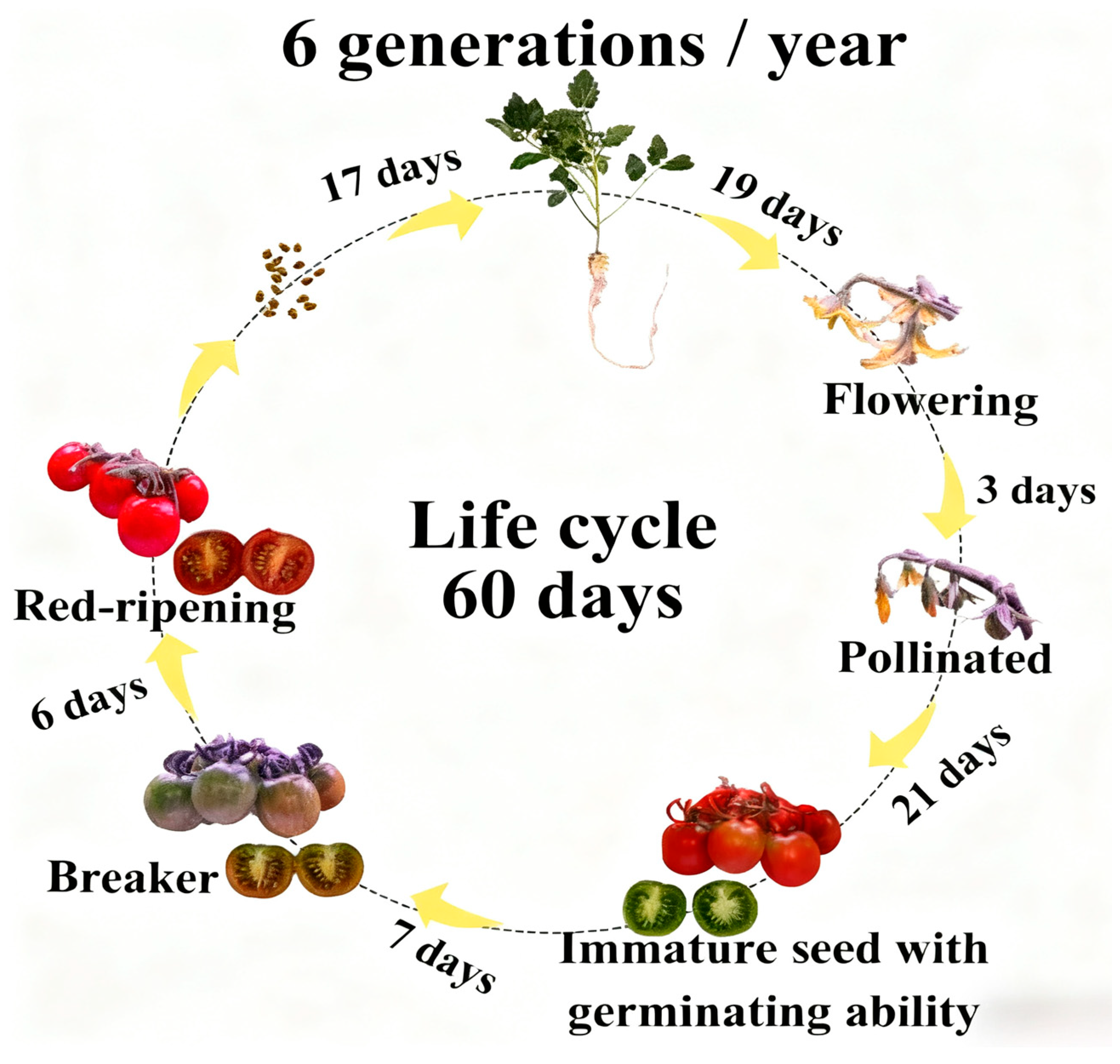

3. Results

3.1. Effects of Light Intensity on the Growth and Development of Tomato

3.2. Effects of Photoperiod on the Growth and Development of Tomato

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Henriques, d.S.D.J.; Abreu, F.B.; Caliman, F.R.B.; Antonio, A.C.; Patel, V.B. Tomatoes: Origin, Cultivation Techniques and Germplasm Resources. In Tomatoes and Tomato Products; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatta, M.; Sandro, P.; Smith, M.R.; Delaney, O.; Voss-Fels, K.P.; Gutierrez, L.; Hickey, L.T. Need for Speed: Manipulating Plant Growth to Accelerate Breeding Cycles. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2021, 60, 101986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samineni, S.; Sen, M.; Sajja, S.B.; Gaur, P.M. Rapid Generation Advance (RGA) in Chickpea to Produce up to Seven Generations per Year and Enable Speed Breeding. Crop J. 2020, 8, 164–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdan, M.F.; Karlson, C.K.S.; Teoh, E.Y.; Lau, S.-E.; Tan, B.C. Genome Editing for Sustainable Crop Improvement and Mitigation of Biotic and Abiotic Stresses. Plants 2022, 11, 2625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Lei, Y.; Huang, X.; Su, W.; Chen, R.; Hao, Y. Crosstalk of Cold and Gibberellin Effects on Bolting and Flowering in Flowering Chinese Cabbage. J. Integr. Agric. 2019, 18, 992–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Watson, A.; Gonzalez-Navarro, O.E.; Ramirez-Gonzalez, R.H.; Yanes, L.; Mendoza-Suárez, M.; Simmonds, J.; Wells, R.; Rayner, T.; Green, P.; et al. Speed Breeding in Growth Chambers and Glasshouses for Crop Breeding and Model Plant Research. Nat. Protoc. 2018, 13, 2944–2963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Globus, R.; Qimron, U. A Technological and Regulatory Outlook on CRISPR Crop Editing. J. Cell. Biochem. 2018, 119, 1291–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, A.; Ghosh, S.; Williams, M.J.; Cuddy, W.S.; Simmonds, J.; Rey, M.-D.; Asyraf Md Hatta, M.; Hinchliffe, A.; Steed, A.; Reynolds, D. Speed Breeding Is a Powerful Tool to Accelerate Crop Research and Breeding. Nat. Plants 2018, 4, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozai, T.; Niu, G. Role of the Plant Factory with Artificial Lighting (PFAL) in Urban Areas. In Plant Factory; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 7–34. [Google Scholar]

- Kapolas, G.; Beris, D.; Katsareli, E.; Livanos, P.; Zografidis, A.; Roussis, A.; Milioni, D.; Haralampidis, K. APRF1 Promotes Flowering under Long Days in Arabidopsis Thaliana. Plant Sci. 2016, 253, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, K.; He, R.; He, X.; Tan, J.; Chen, Y.; Li, Y.; Liu, R.; Huang, Y.; Liu, H. Speed Breeding Scheme of Hot Pepper through Light Environment Modification. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezazadeh, A.; Harkess, R.L.; Telmadarrehei, T. The Effect of Light Intensity and Temperature on Flowering and Morphology of Potted Red Firespike. Horticulturae 2018, 4, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalil, A.A.; Basilio, J.E.D.; Ellomer, G.A.; Alejandro, R.L.; Natividad, R.L.M. The Effect of Different Light Intensities on the Growth and Yield of Tomato (Lycopersicon Esculentum Mill.). IJMRA 2023, 6, 2550–2556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimeno-Páez, E.; Prohens, J.; Moreno-Cerveró, M.; de Luis-Margarit, A.; Díez, M.J.; Gramazio, P. Agronomic Treatments Combined with Embryo Rescue for Rapid Generation Advancement in Tomato Speed Breeding. Hortic. Plant J. 2025, 11, 239–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Shou, W.; Huang, K.; Zhou, S.; Li, G.; Tang, G.; Xiu, X.; Xu, G.; Jin, B. The Current Situation and Trend of Tomato Cultivation in China. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2000, 22, 379–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, R.W.; Hisamatsu, T.; Goldschmidt, E.E.; Blundell, C. The Nature of Floral Signals in Arabidopsis. I. Photosynthesis and a Far-Red Photoresponse Independently Regulate Flowering by Increasing Expression of FLOWERING LOCUS T (FT). J. Exp. Bot. 2008, 59, 3811–3820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davarzani, M.; Aliniaeifard, S.; Mehrjerdi, M.Z.; Roozban, M.R.; Saeedi, S.A.; Gruda, N.S. Optimizing Supplemental Light Spectrum Improves Growth and Yield of Cut Roses. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 21381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, W. Effects of Temperature, Photoperiod and Light Intensity on Growth and Flowering in Eustoma grandiflorum. HST 2015, 33, 349–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Eguchi, M.; Gui, Y.; Iwasaki, Y. Evaluating the Effect of Light Intensity on Flower Development Uniformity in Strawberry (Fragaria× Ananassa) under Early Induction Conditions in Forcing Culture. HortScience 2020, 55, 670–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanoue, J.; Leonardos, E.D.; Grodzinski, B. Effects of Light Quality and Intensity on Diurnal Patterns and Rates of Photo-Assimilate Translocation and Transpiration in Tomato Leaves. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.-X.; Xu, Z.-G.; Liu, X.-Y.; Tang, C.-M.; Wang, L.-W.; Han, X. Effects of Light Intensity on the Growth and Leaf Development of Young Tomato Plants Grown under a Combination of Red and Blue Light. Sci. Hortic. 2013, 153, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizal, G.; Karki, S.; Alcasid, M.; Montecillo, F.; Acebron, K.; Larazo, N.; Garcia, R.; Slamet-Loedin, I.H.; Quick, W.P. Shortening the Breeding Cycle of Sorghum, a Model Crop for Research. Crop Sci. 2014, 54, 520–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Barrios, P.; Bhatta, M.; Halley, M.; Sandro, P.; Gutiérrez, L. Speed Breeding and Early Panicle Harvest Accelerates Oat (Avena Sativa L.) Breeding Cycles. Crop Sci. 2021, 61, 320–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Wu, Q.; Zeng, X.; Li, F.; Zhang, B.; Jiang, Y.; Hui, J. Effect of Photoperiod Duration on Flower Bud Differentiation and Related Gene Expression in Bougainvillea Glabra “Sao Paulo”. Front. Biosci. 2024, 29, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Li, R.; Bu, C.; Zhu, C.; Miao, C.; Zhang, Y.; Cui, J.; Jiang, Y.; Ding, X. Photoperiodic Effect on Growth, Photosynthesis, Mineral Elements, and Metabolome of Tomato Seedlings in a Plant Factory. Plants 2024, 13, 3119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhu, K.; Wang, X.; Yan, J.; Zhu, H.; Zhang, N.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Liu, Y.; Bu, X.; et al. Manipulation of Artificial Light Environment Improves Plant Biomass and Fruit Nutritional Quality in Tomato. J. Adv. Res. 2025, 75, 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hu, Y.; He, X.; Ju, J.; Zhang, M.; Yang, X.; Song, J.; Liu, H. A Scheme for Speed Breeding of Tomato Through Modification of the Light Environment. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 1488. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121488

Hu Y, He X, Ju J, Zhang M, Yang X, Song J, Liu H. A Scheme for Speed Breeding of Tomato Through Modification of the Light Environment. Horticulturae. 2025; 11(12):1488. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121488

Chicago/Turabian StyleHu, Youzhi, Xinyang He, Jun Ju, Minggui Zhang, Xiaolong Yang, Jiali Song, and Houcheng Liu. 2025. "A Scheme for Speed Breeding of Tomato Through Modification of the Light Environment" Horticulturae 11, no. 12: 1488. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121488

APA StyleHu, Y., He, X., Ju, J., Zhang, M., Yang, X., Song, J., & Liu, H. (2025). A Scheme for Speed Breeding of Tomato Through Modification of the Light Environment. Horticulturae, 11(12), 1488. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121488