Effects of Pre-Harvest Hexanal and Post-Harvest 1-Methylcyclopropene Treatments on Bitter Pit Incidence and Fruit Quality in ‘Arisoo’ Apples

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

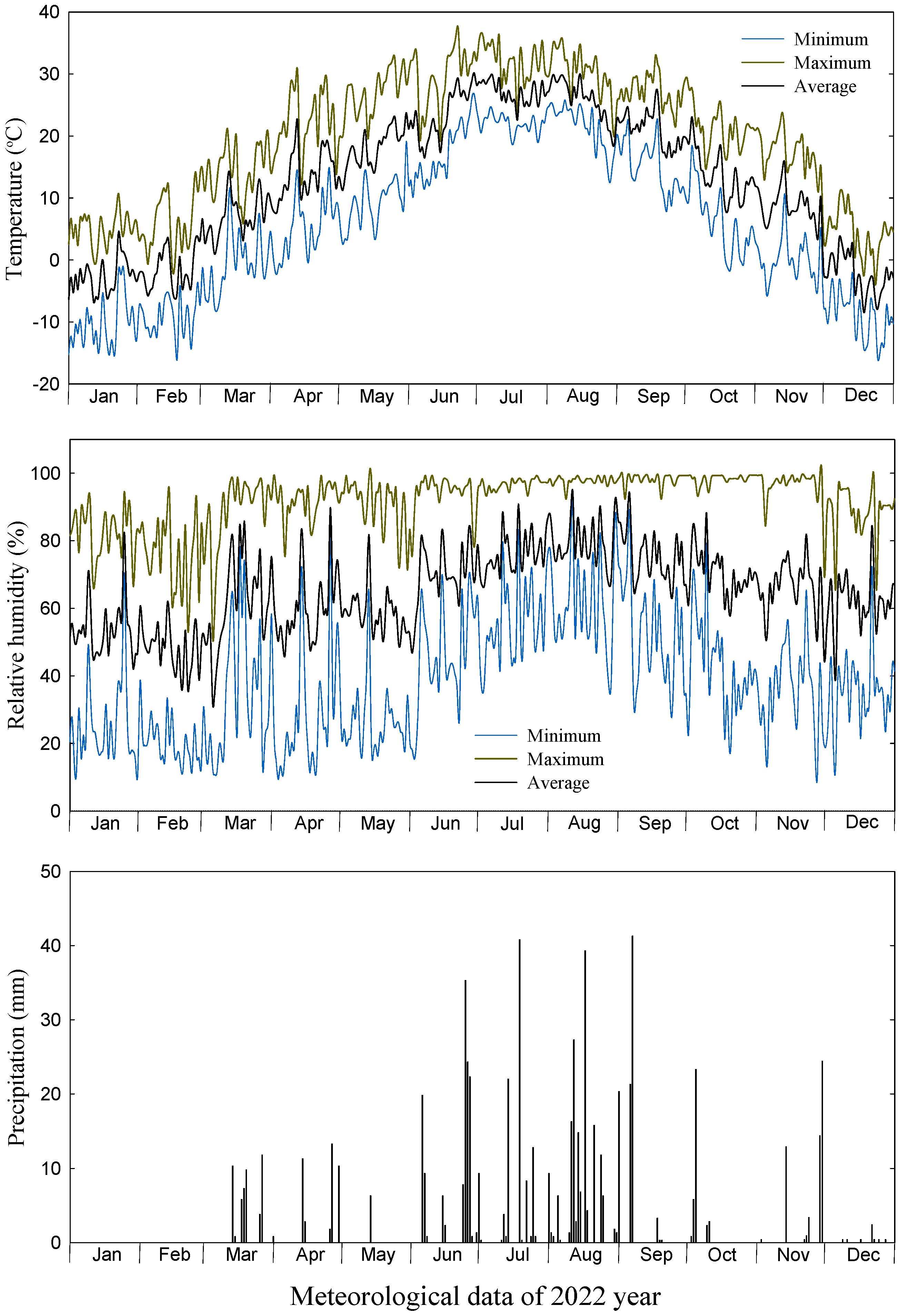

2.1. Plant Materials, Treatments, and Storage Conditions

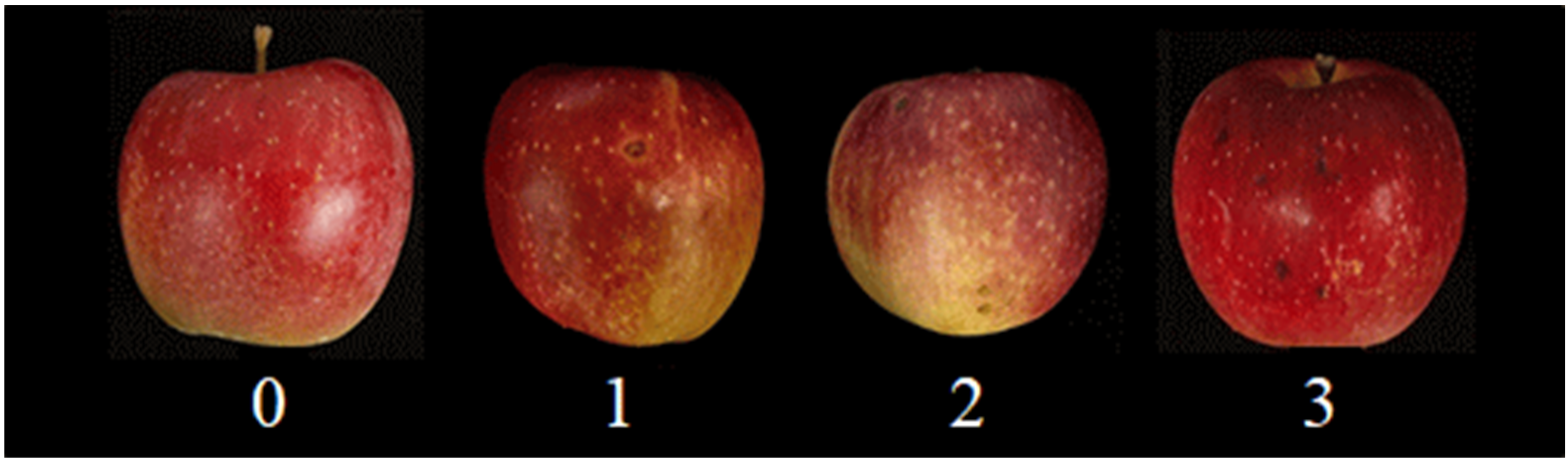

2.2. Bitter Pit Incidence Evaluations

2.3. Evaluation of Fruit Quality Attributes

2.4. Polyphenol Oxidase (PPO) Activity

2.5. Extraction of Cell Wall Materials

2.6. Determination of Total Sugar and Uronic Acid Contents

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Effects of Hexanal Treatment on Bitter Pit Incidence and Fruit Quality of ‘Arisoo’ Apples at Harvest

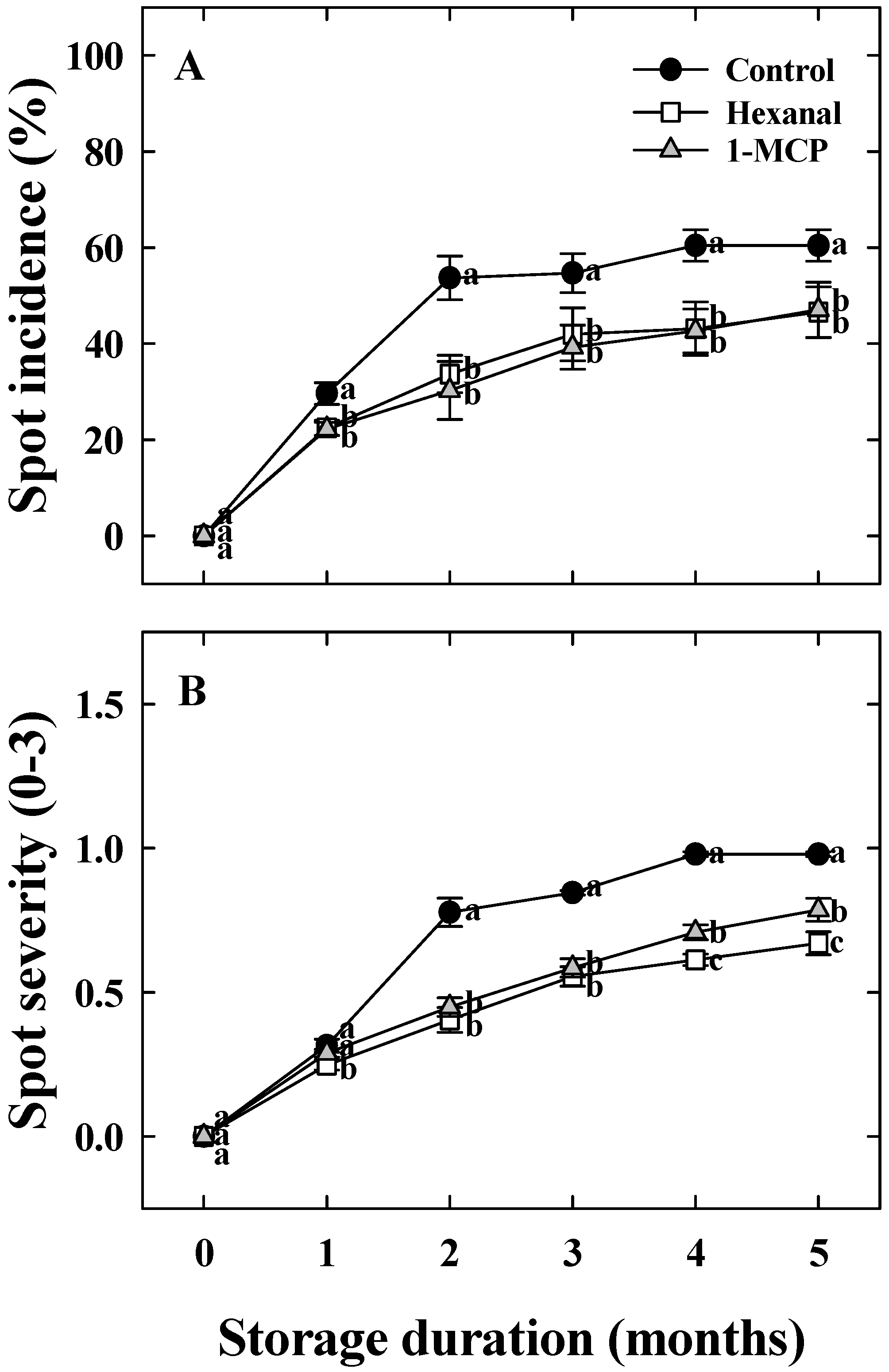

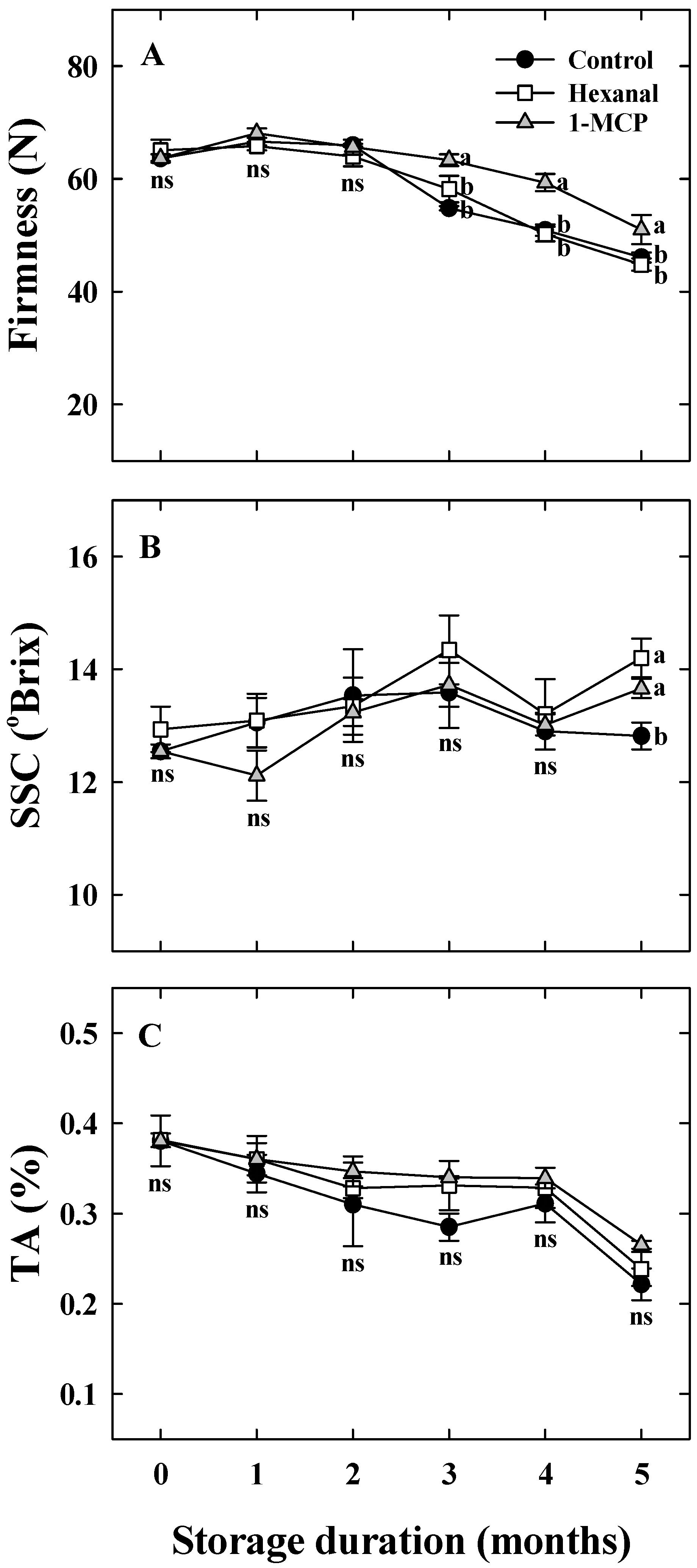

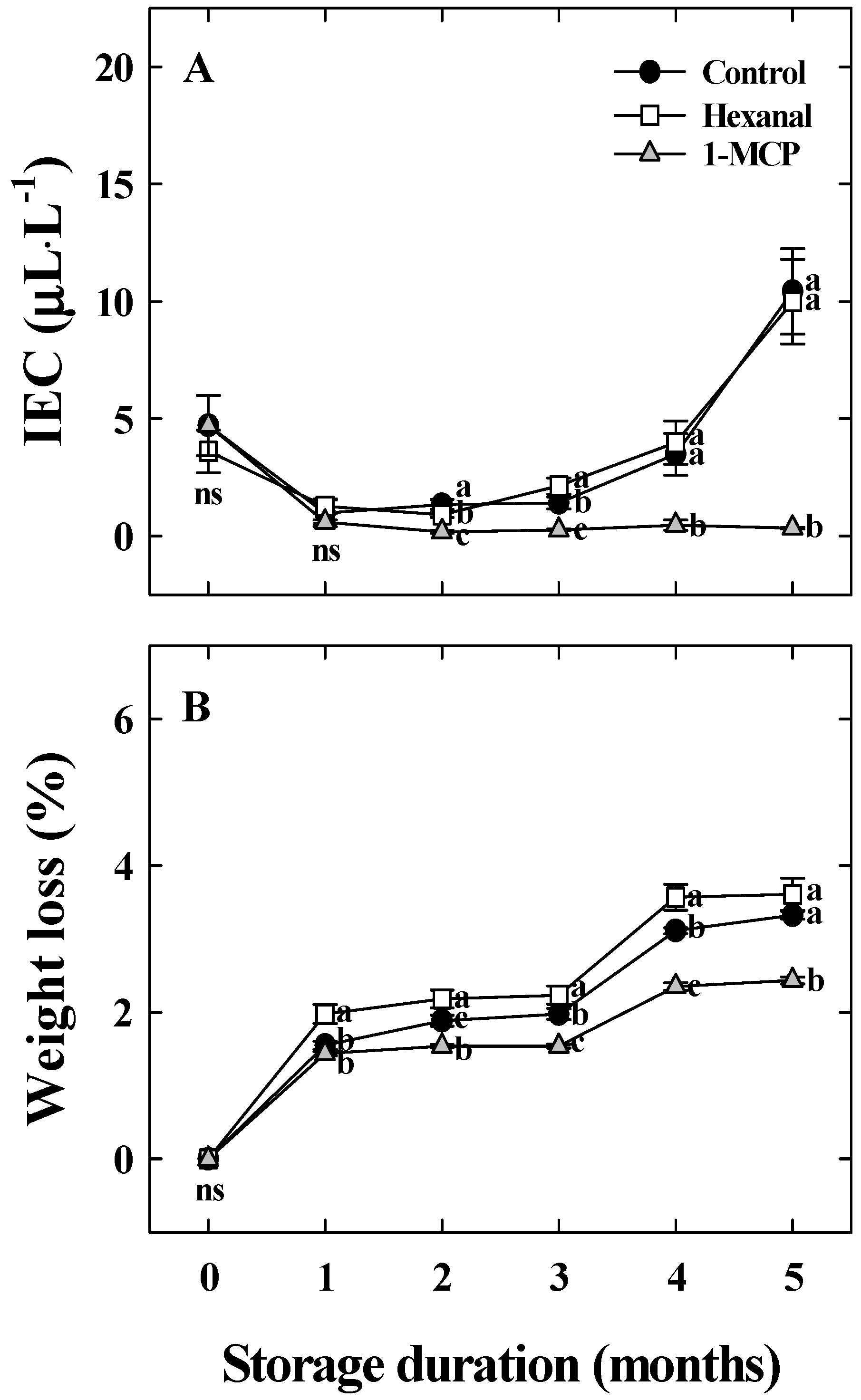

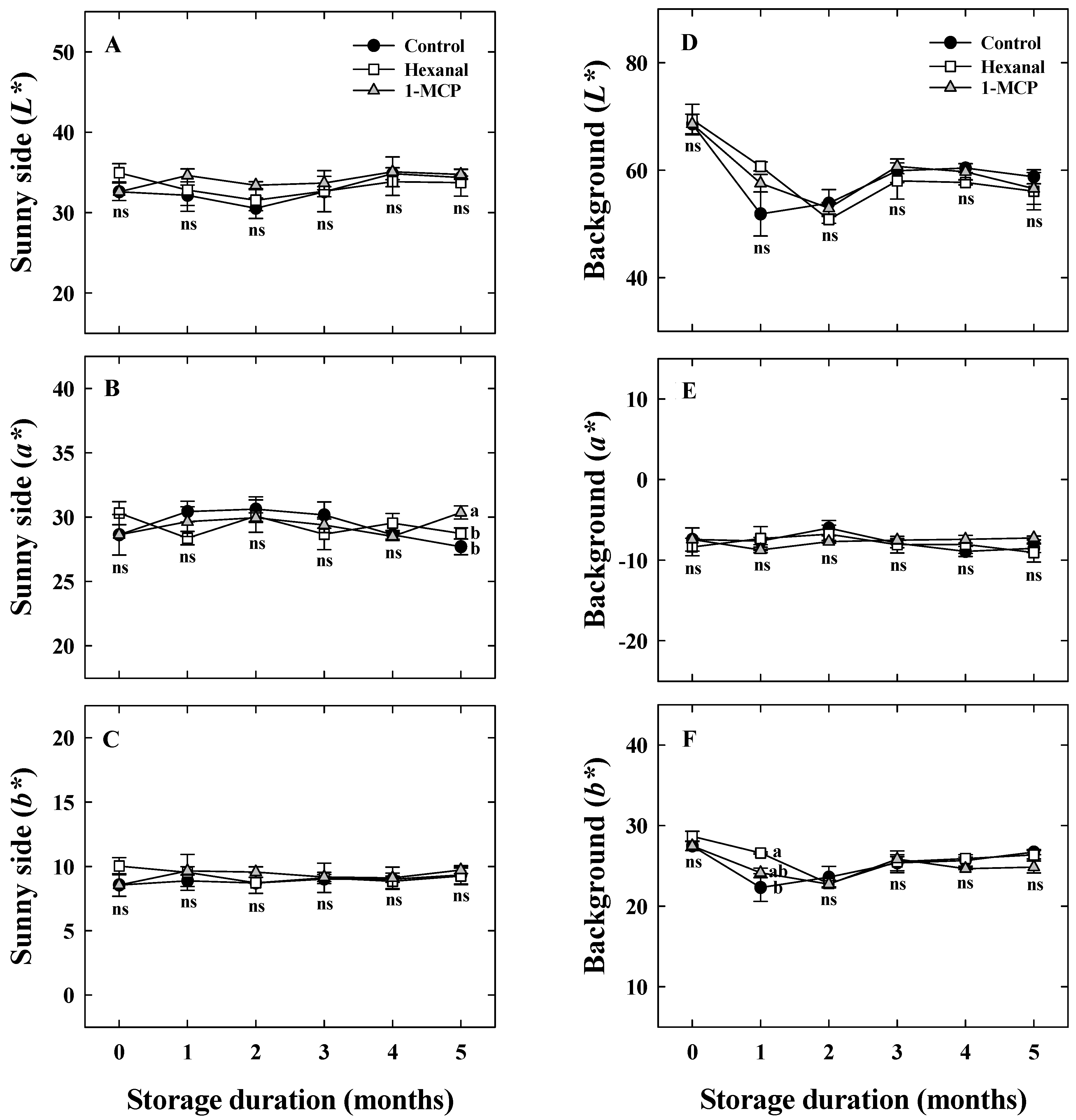

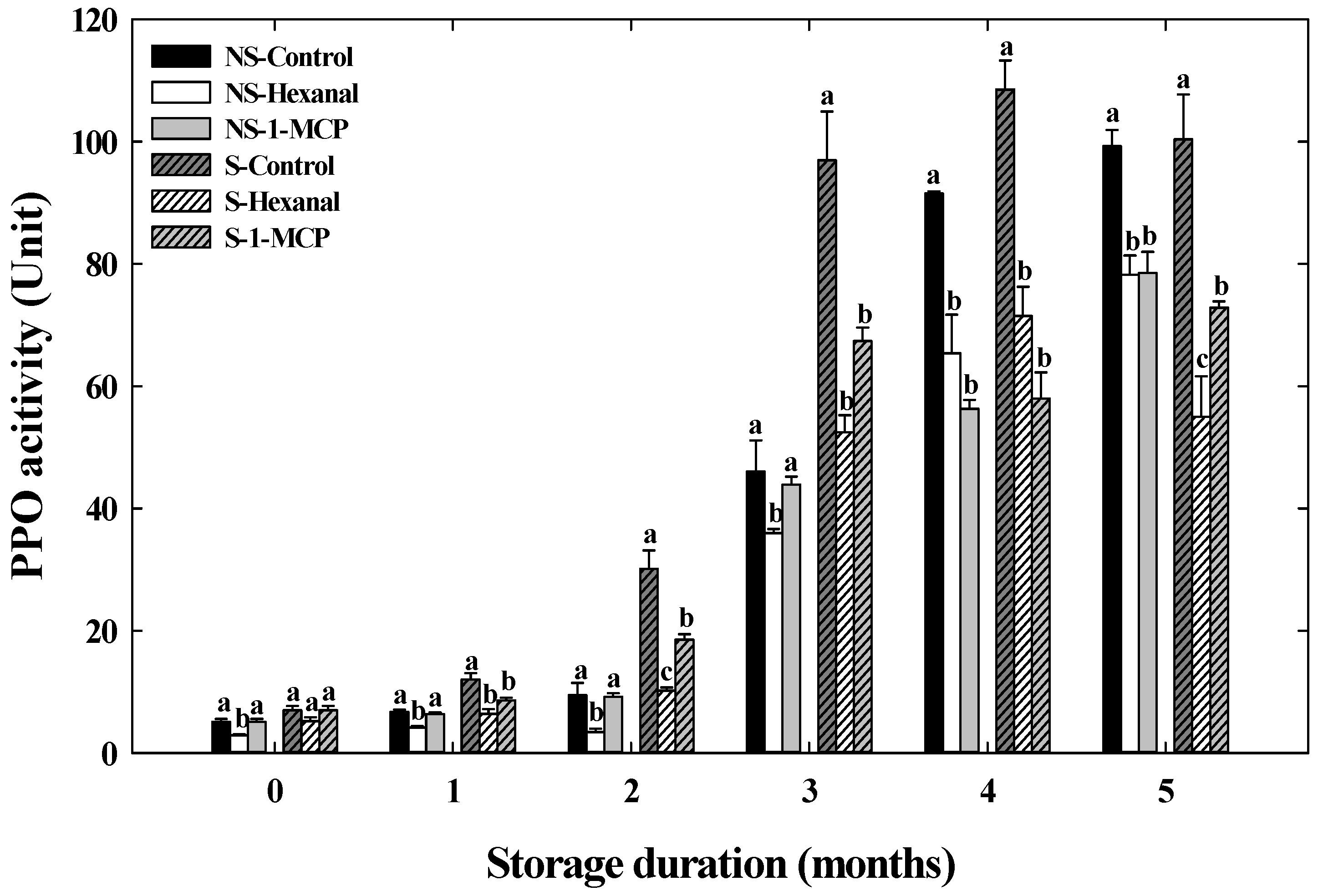

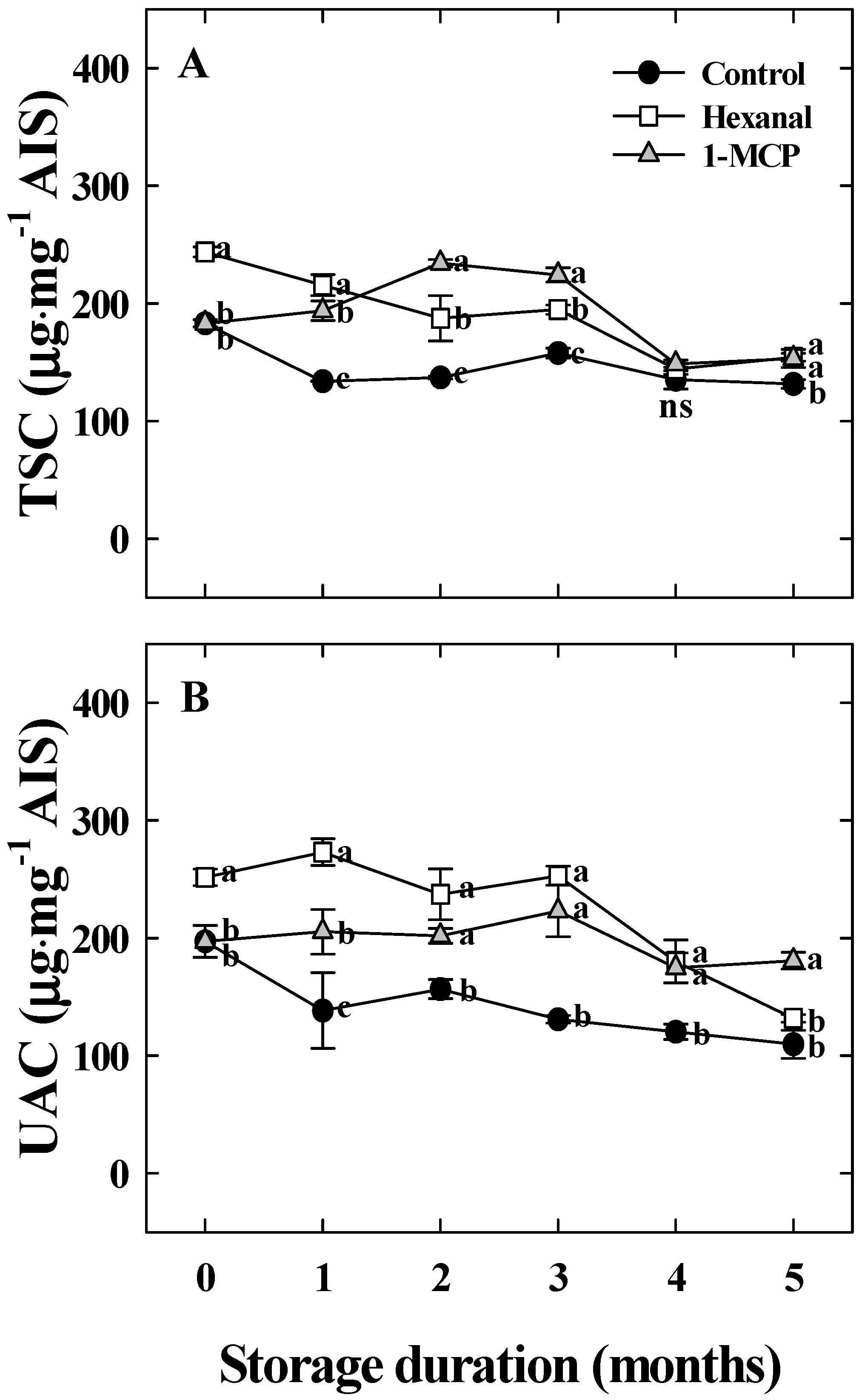

3.2. Effects of Hexanal and 1-MCP Treatment on Bitter Pit Incidence, Fruit Quality, PPO, TS, and UA Activity of ‘Arisoo’ Apples During Cold Storage

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kwon, Y.S.; Kwon, S.I.; Kim, J.H.; Park, M.Y.; Park, J.T.; Lee, J. ‘Arisoo’, a midseason apple. Hortic. Sci. 2021, 56, 1139–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, J. Effects of 1-Methylcyclopropene (1-MCP) Application on Fruit Quality Attributes in ‘Arisoo’ and ‘Picnic’ Apples During Cold Storage. Master’s Thesis, Kyungpook National University, Daegu, Republic of Korea, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Research Report: Development of Cultivation Technologies for ‘Arisoo’ Apples. Available online: https://scienceon.kisti.re.kr/commons/util/originalView.do?cn=TRKO201900015907&dbt=TRKO&rn= (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Ferguson, I.B.; Watkins, C.B. Bitter pit in apple fruit. Hortic. Rev. 2011, 11, 289–355. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D.H.; Byun, J.K.; Choi, C.; Choi, D.G.; Kang, I.K. The effect of calcium chloride, prohexadione-Ca and Ca-coated paper bagging on reduction of bitter pit in ‘Gamhong’ apple. Korean J. Hortic. Sci. Technol. 2008, 26, 367–371. [Google Scholar]

- Lötze, E.; Joubert, J.; Theron, K.I. Evaluating pre-harvest foliar calcium applications to increase fruit calcium and reduce bitter pit in ‘Golden Delicious’ apples. Sci. Hortic. 2008, 116, 299–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.Y.; Kwon, S.I.; Kwon, Y.S.; Kwon, H.J.; Park, J.T.; Lee, D.Y.; Lee, Y.S. Different treatments induce the development of fruit. In Proceedings of the 38th Annual Meeting of Korean Society for Horticultural Science, Gyeongju, Republic of Korea, 11 November 2020; p. 157. [Google Scholar]

- Cheema, A.; Padmanabhan, P.; Subramanian, J.; Blom, T.; Paliyath, G. Improving quality of greenhouse tomato (Solanum lycoperscum L.) by pre- and postharvest application of hexanal-containing formulations. Postharvest. Biol. Technol. 2014, 95, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paliyath, G.; Padmanabhan, P. Preharvest and postharvest technologies based on hexanal: An overview. In Postharvest Biology and Nanotechnology; John Wiley and Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 89–101. [Google Scholar]

- Paliyath, G.; Tiwari, K.; Yuan, H.; Whitaker, B.D. Structural deterioration in produce: Phospholipase D, membrane deterioration, and senescence. In Postharvest Biology and Technology of Fruits, Vegetables, and Flowers; John Wiley and Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008; Volume 19, p. 33. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.; Viljoen, A.M. Gerniol—A review of a commercially important fragrance material. S. Afric. J. Bot. 2010, 76, 643–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesa, T.; Munné-Bosch, S. ɑ-Tocopherol in chloroplasts: Nothing more than an antioxidant? Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2023, 74, 102400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, X.; Gong, M.; Zhang, Q.; Tan, H.; Li, L.; Tang, Y.; Li, Z.; Peng, M.; Deng, W. Metabolism and regulation of ascorbic acid in fruits. Plants 2022, 18, 1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mthembu, S.S.L.; Magwaza, L.S.; Tesfay, S.Z.; Midtshwa, A. Mechanism of enhanced freshness formulation in optimizing antioxidant retention of gold kiwifruit (Actinida chinensis) harvested at two maturity stages. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 7, 1286677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeBrouwer, E.J.; Sriskantharajah, K.; El Kayal, W.; Sullivan, J.A.; Paliyath, G.; Subramanian, J. Pre-harvest hexanal spray reduces bitter pit and enhances post-harvest quality in ‘Honeycrisp’ apples (Malus domestica Borkh.). Sci. Hortic. 2020, 273, 109610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.K.; El Kayal, W.; Sullivan, J.A.; Paliyath, G.; Subramanian, J. Pre-harvest application of hexanal formulation enhances shelf life and quality of ‘Fantasia’ nectarines by regulating membrane and cell wall catabolism-associated genes. Sci. Hortic. 2018, 229, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anusuya, P.; Nagaraj, R.; Janavi, G.J.; Subramanian, K.S.; Paliyath, G.; Subramanian, J. Pre-harvest sprays of hexanal formulation for extending retention and shelf-life of mango (Mangifera indica L.) fruits. Sci. Hortic. 2016, 211, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, K.S.; Dhaliwal, H.S.; Mahajanc, B.V.C.; Paliyath, G.; Boorae, R.S. Enhancing post-harvest shelf life and quality of guava (Psidium guajava L.) cv. Allahabad Safeda by pre-harvest application of hexanal containing aqueous formulation. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2016, 112, 224–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, C.B. The use of 1-methylcyclopropene (1-MCP) on fruits and vegetables. Biotechnol. Adv. 2006, 24, 389–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattheis, J.P.; Rudell, D.R.; Hanrahan, I. Impacts of 1-methylcyclopropene and controlled atmosphere established during conditioning on development of bitter pit in ‘Honeycrisp’ apples. HortScience 2017, 52, 132–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, B.S.; Oh, S.Y.; Lee, J.W.; Hwang, Y.S. Influence of 1-methylcyclopropene treatment time on the fruit quality in the ‘Fuji’ apple (Malus domestica). Korean J. Hortic. Sci. Technol. 2007, 25, 191–195. [Google Scholar]

- Manenoi, A.; Paull, R.E. Papaya fruit softening, endoxylanase gene expression, protein and activity. Plant Physiol. 2007, 131, 470–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sañudo-Barajas, J.A.; Labavitch, J.; Greve, C.; Osuna-Enciso, T.; Muy-Rangel, D.; Siller-Cepeda, J. Cell wall disassembly during papaya softening: Role of ethylene in changes in composition, pectin-derived oligomers (PDOs) production and wall hydrolases. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2009, 51, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, J.; Kim, S.H.; Kwon, J.G.; Cho, Y.J.; Kang, I.K. Effects of 1-methylcyclopropene treatments on fruit quality attributes and cell wall metabolism in cold stored ‘Summer Prince’ and ‘Summer King’ apples. Hortic. Sci. Technol. 2020, 5, 660–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoffe, A.Y.; Nock, J.F.; Zhang, Y.; Watkins, C.B. Physiological disorder development of ‘Honeycrisp’ apples after pre-and post-harvest 1-methycyclopropene (1-MCP) treatments. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2021, 182, 111703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, V.G.; Lee, Y.; Park, J.; Win, N.M.; Kwon, S.I.; Yang, S.; Kim, S. Heat stress and water irrigation management effects on the fruit color and quality of ‘Hongro’ apples. Agriculture 2024, 14, 761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, D.H.; Park, J.J.; Olawuyi, I.F.; Lee, W.Y. Quality of White mushroom (Agaricus bisporus) under argon-and nitrogen-based controlled atmosphere storage. Sci. Hortic. 2020, 265, 109229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, J.; Suk, Y.; Lee, J.; Jung, H.Y.; Choung, M.G.; Park, K.I.; Han, J.S.; Cho, Y.J.; Lee, D.H.; Kang, I.K. Preharvest sprayable 1-methylcyopropene (1-MCP) effects on fruit quality attributes and cell wall metabolism in cold stored ‘Fuji’ apples. Hortic. Sci. Technol. 2018, 36, 853–862. [Google Scholar]

- Bitter, T.; Muir, H.M. A modified uronic acid carbazole reaction. Anal. Biochem. 1962, 4, 330–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Win, N.M.; Do, V.G.; Kwon, J.G.; Park, J.T.; Park, J.; Lee, Y.; Kweon, H.J.; Kang, I.K.; Kwon, S.I.; Kim, S. Fruit bag removal timing influences fruit coloration, quality, and physiological disorders in ‘Arisoo’ apples. Plants 2025, 14, 2923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Freitas, S.T.; do Amarante, C.V.T.; Labavitch, J.M.; Mitcham, E.J. Cellular approach to understand bitter pit development in apple fruit. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2010, 57, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hocking, B.; Tyerman, S.D.; Burton, R.A.; Gilliham, M. Fruit calcium: Transport and physiology. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miqueloto, A.; do Amarante, C.V.T.; Steffens, C.A.; dos Santos, A.; Mitcham, E. Relationship between xylem functionality, calcium content and the incidence of bitter pit in apple fruit. Sci. Hortic. 2014, 165, 319–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashintha, G.N.; Sunny, A.C.; Nisha, R. Effect of pre-harvest and post-harvest hexanal treatments on fruits and vegetables: A review. Agric. Rev. 2020, 41, 124–131. [Google Scholar]

- El Kayal, W.; Paliyath, G.; Sullivan, J.A.; Subramanian, J. Phospholipase D inhibition by hexanal is associated with calcium signal transduction events in raspberry. Hortic. Res. 2017, 4, 17042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watkins, C.B.; Mattheis, J.P. Apple. In Postharvest Physiological Disorders in Fruits and Vegetables; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2019; pp. 165–206. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.Y.; Kim, K.O.; Yoo, J.; Win, N.M.; Lee, J.; Choung, M.G.; Jung, H.Y.; Kang, I.K. Effects of aminoethoxyvinylglycine, sprayable 1-methylcyclopropene (1-MCP) and fumigation 1-MCP treatments on fruit quality attributes in cold-stored ‘Jonathan’ apples. Korean J. Food Preserv. 2016, 23, 453–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Win, N.M.; Yoo, J.; Kwon, S.I.; Watkins, C.B.; Kang, I.K. Characterization of fruit quality attributes and cell wall metabolism in 1-methylcyclopropene (1-MCP) treated ‘Summer King’ and ‘Green Ball’ apples during cold storage. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, J.; Kwon, H.W.; Kwon, J.G.; Win, N.M.; Kang, I.K. Effects of Salicylic acid and 1-methylcyclopropene treatments on fruit quality and cell wall hydrolases of ‘Hwangok’ apples during cold and shelf-life storage. Hortic. Sci. Technol. 2022, 40, 539–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupasinghe, H.P.V.; Paliyath, G.; Murr, D.P. Sesquiterpene alpha-farnesene synthase: Partial purification, characterization, and activity in relation to superficial scald development in apples. Sci. Hortic. 2000, 125, 111–119. [Google Scholar]

- Niu, J.; Hou, Z.; Ou, Z.; Hui, W. Comparative study of effects of resveratrol, 1-MCP and DPA treatments on postharvest quality and superficial scald of ‘Starkrimson’ apples. Sci. Hortic. 2018, 240, 516–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lurie, S.; Watkins, C.B. Superficial scald, its etiology and control. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2012, 65, 44–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichanporn, I.; Srilaong, V.; Wongs-Aree, C.; Kanlayanarat, S. Postharvest physiology and browning of longkong (Aglaia dookkoo Griff.) fruit under ambient conditions. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2009, 52, 294–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeEll, J.R.; Lum, G.B.; Mostofi, Y.; Lesage, S.K. Timing of ethylene inhibition affects internal browning and quality of ‘Gala apples in long-term low oxygen storage. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 914441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, S.; Arora, N.K.; Gill, K.B.S.; Sharma, S.; Gill, M.I.S. Hexanal formulation reduces rachis browning and postharvest losses in table grapes cv. ‘Flame Seedless’. Sci. Hortic. 2019, 248, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, D.J. The role of cell wall hydrolases in fruit softening. Hortic. Rev. 1983, 5, 169–219. [Google Scholar]

| Treatment | Bitter Pit Incidence (%) | Incidence Severity (0–3) y | Bitter Pit Severity Index (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |||

| Control | 20.6 ± 0.7 z | 0.34 ± 0.02 | 78.4 ± 3.4 | 14.3 ± 4.4 | 2.2 ± 0.7 | 5.0 ± 0.8 |

| Hexanal | 13.2 ± 0.8 | 0.18 ± 0.02 | 82.9 ± 1.8 | 16.6 ± 1.8 | 0.6 ± 0.7 | 0.0 ± 0.0 |

| Significance | ** | ** | ns | ns | ns | * |

| Treatment | Fruit Qualities | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fruit Weight (g) | Firmness (N/Φ11 mm) | SSC (°Brix) | TA (%) | IEC (μL·L−1) | SPI (1–8) | |

| Control | 269.4 ± 11.4 z | 63.6 ± 0.6 | 12.5 ± 0.1 | 0.38 ± 0.02 | 4.72 ± 1.06 | 7.06 ± 0.12 |

| Hexanal | 298.3 ± 14.5 | 65.1 ± 1.6 | 12.9 ± 0.3 | 0.38 ± 0.01 | 3.61 ± 0.74 | 6.66 ± 0.27 |

| Significance | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| Fruit color (sun-exposed side) | Fruit color (sun-shaded side) | |||||

| L* | a* | b* | L* | a* | b* | |

| Control | 32.6 ± 0.9 | 28.6 ± 1.3 | 8.6 ± 0.7 | 68.6 ± 1.5 | −7.4 ± 1.2 | 27.5 ± 0.5 |

| Hexanal | 35.0 ± 0.9 | 30.3 ± 0.7 | 10.0 ± 0.5 | 69.4 ± 2.3 | −8.4 ± 0.9 | 28.7 ± 0.5 |

| Significance | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, J.-Y.; Kwon, J.-G.; Kim, K.; Yoo, J.; Kim, S.; Win, N.M.; Kang, I.-K. Effects of Pre-Harvest Hexanal and Post-Harvest 1-Methylcyclopropene Treatments on Bitter Pit Incidence and Fruit Quality in ‘Arisoo’ Apples. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 1468. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121468

Lee J-Y, Kwon J-G, Kim K, Yoo J, Kim S, Win NM, Kang I-K. Effects of Pre-Harvest Hexanal and Post-Harvest 1-Methylcyclopropene Treatments on Bitter Pit Incidence and Fruit Quality in ‘Arisoo’ Apples. Horticulturae. 2025; 11(12):1468. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121468

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Jun-Yong, Jung-Geun Kwon, Kyoungook Kim, Jingi Yoo, Seonae Kim, Nay Myo Win, and In-Kyu Kang. 2025. "Effects of Pre-Harvest Hexanal and Post-Harvest 1-Methylcyclopropene Treatments on Bitter Pit Incidence and Fruit Quality in ‘Arisoo’ Apples" Horticulturae 11, no. 12: 1468. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121468

APA StyleLee, J.-Y., Kwon, J.-G., Kim, K., Yoo, J., Kim, S., Win, N. M., & Kang, I.-K. (2025). Effects of Pre-Harvest Hexanal and Post-Harvest 1-Methylcyclopropene Treatments on Bitter Pit Incidence and Fruit Quality in ‘Arisoo’ Apples. Horticulturae, 11(12), 1468. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121468