Silica Nanoparticles Improve Drought Tolerance in Ginger by Modulating the AsA-GSH Pathway, the Glyoxalase System and Photosynthetic Metabolism

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material and Treatment

2.2. FDA-PI Staining in Ginger Root

2.3. Analysis of Chlorophyll Content, Photosynthetic Parameters and Chlorophyll Fluorescence

2.4. Analysis of Stomatal Aperture

2.5. Analysis of Enzyme Activities

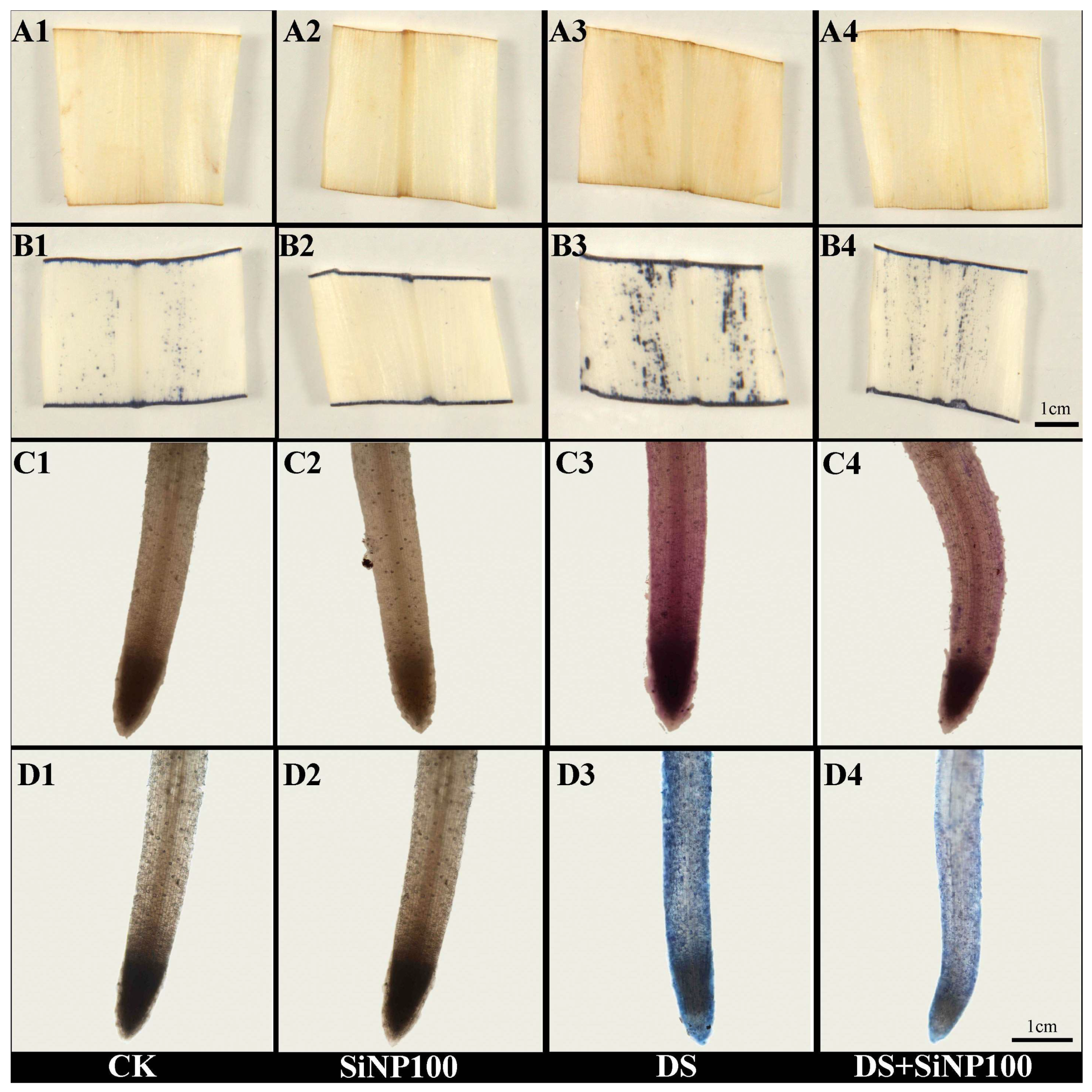

2.6. Analyses of Histochemical Staining in the Ginger

2.7. Determination of Related Substance Content

2.8. RT-qPCR Analysis

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Effects of SiNP100 on the Biomass of Ginger

3.2. Effects of SiNP100 on Photosynthetic Pigments and Photosynthesis-Related Parameters

3.3. Effect of SiNP100 on Plant Stomatal Properties Under Drought Stress

3.4. Effects of SiNP100 on OS Markers and Antioxidant Enzyme Activities

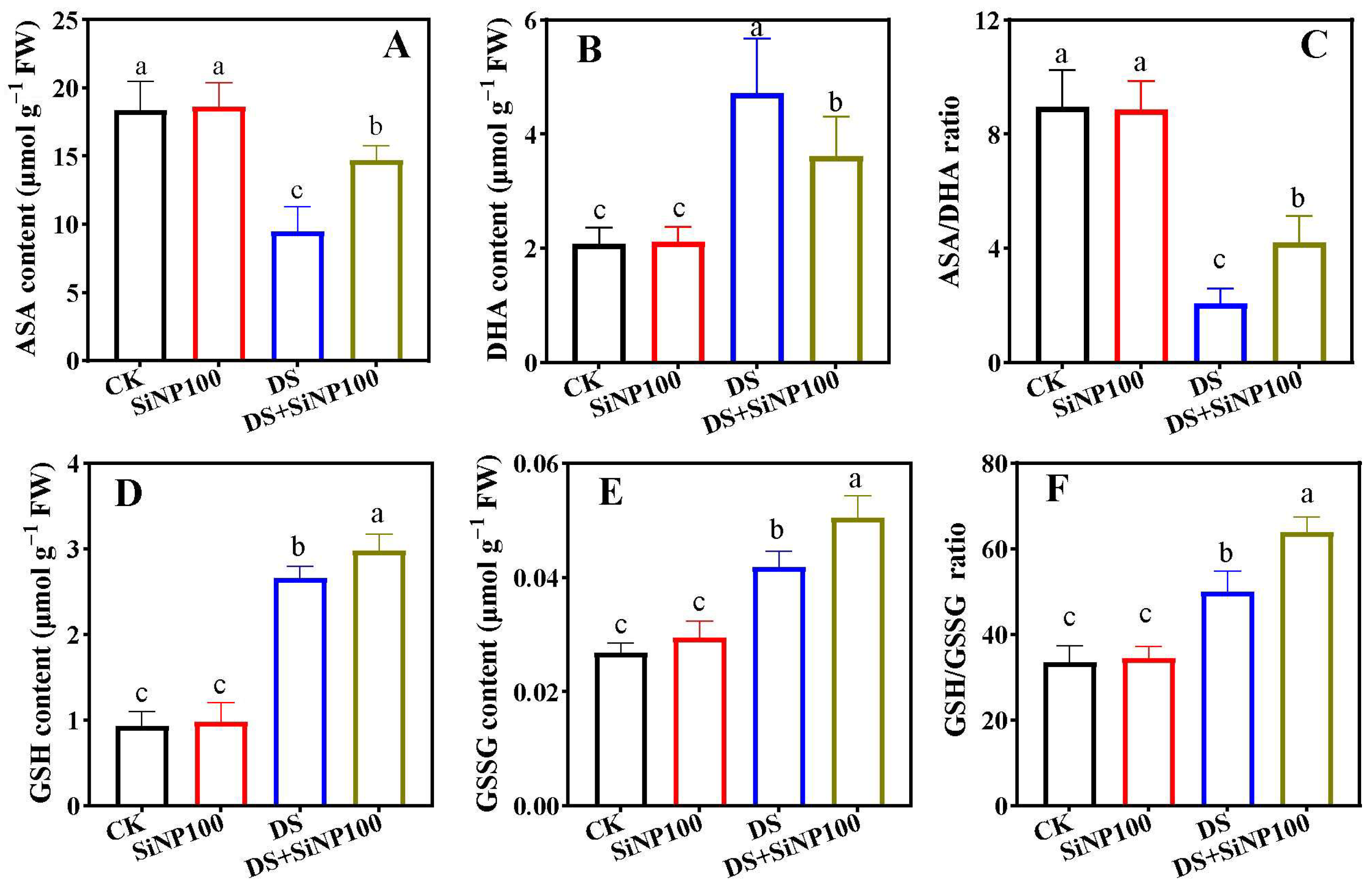

3.5. Effects of SiNP100 on Ascorbate and Glutathione Pool

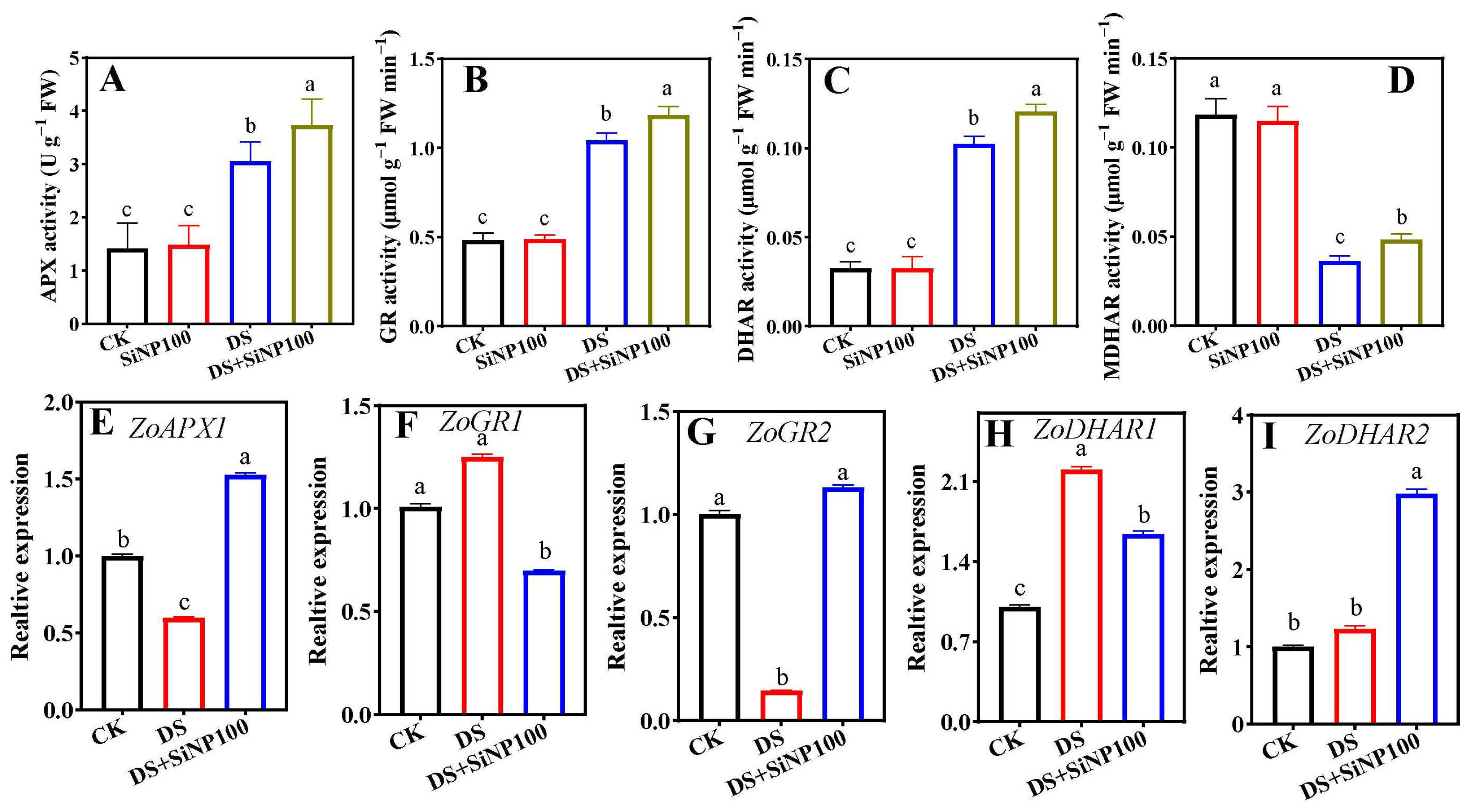

3.6. Effects of SiNP100 on AsA-GSH Cycle Enzymes and Related Gene Expression

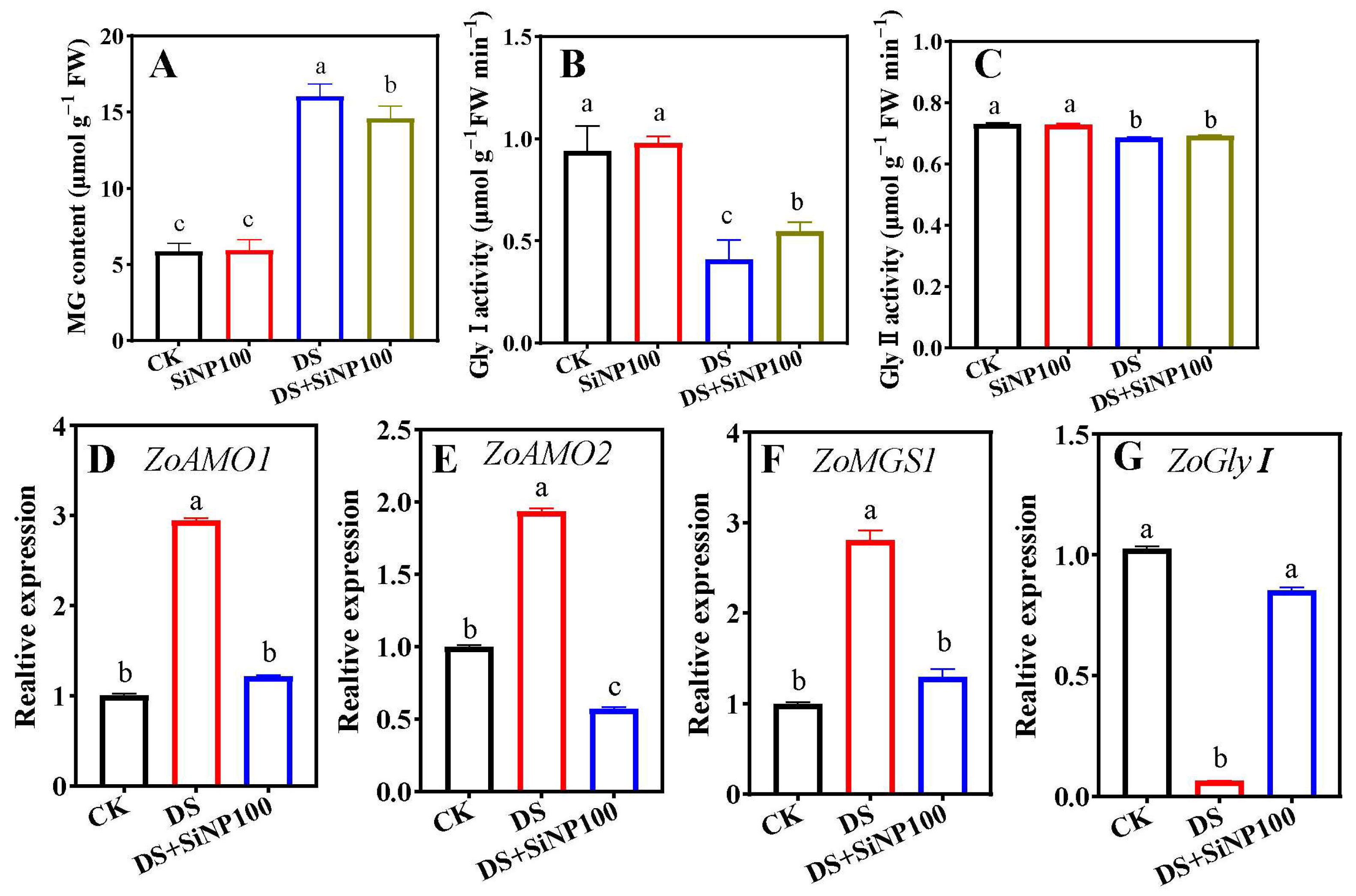

3.7. Effects of SiNP100 on Glyoxalse System Enzymes and Related Gene Expression

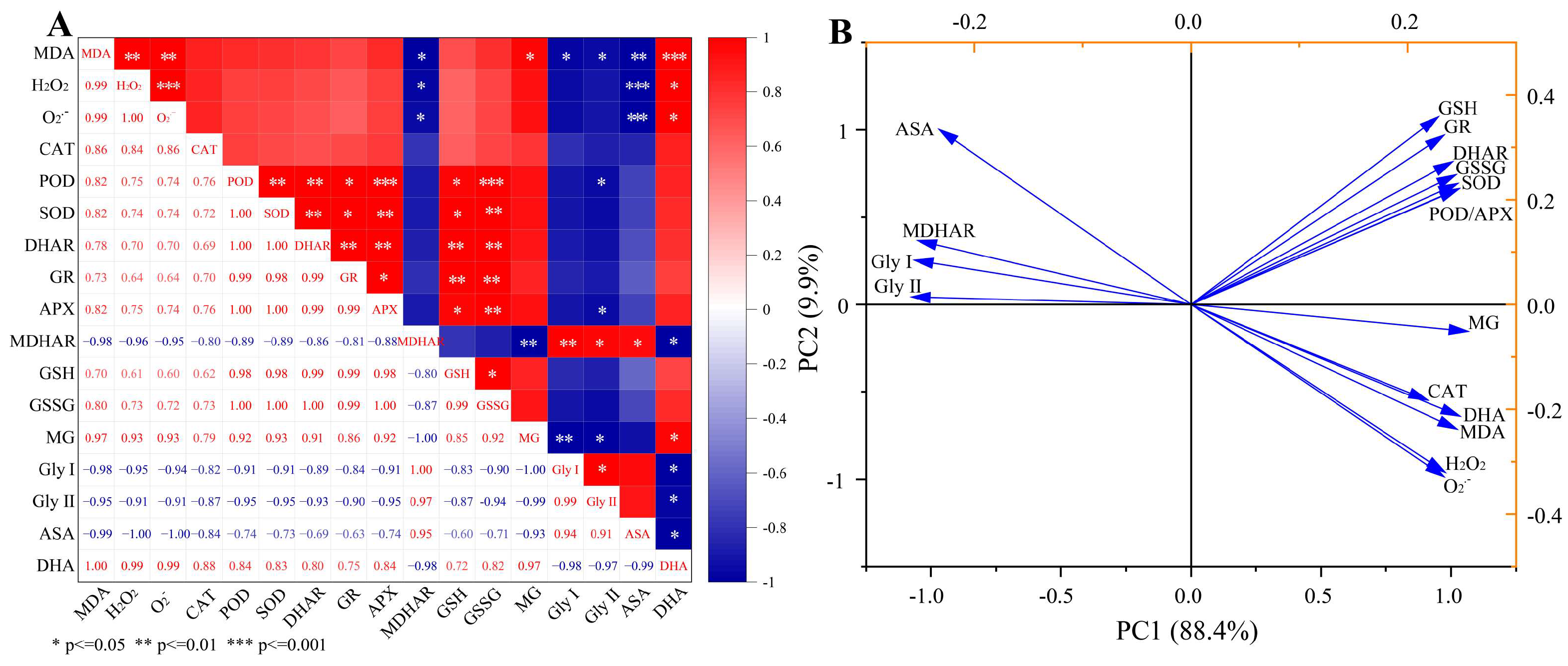

3.8. Pearson Correlation and Principal Component Analysis

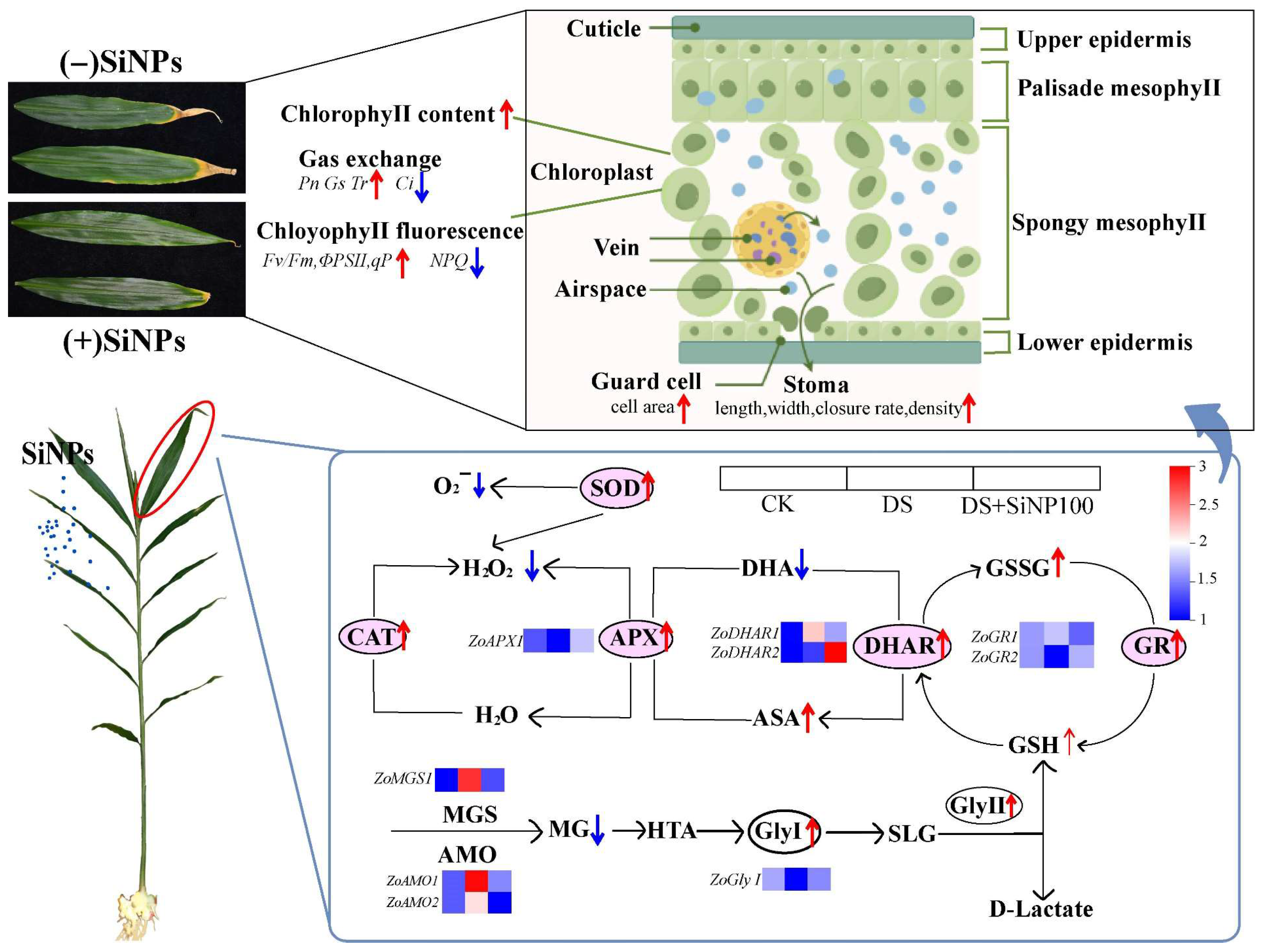

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Feng, D.; Liu, W.; Chen, K.; Ning, S.; Gao, Q.; Chen, J.; Liu, J.; Sun, X.; Xu, W. Exogenous Substances Used to Relieve Plants from Drought Stress and Their Associated Underlying Mechanisms. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasanuzzaman, M.; Bhuyan, M.H.M.B.; Zulfiqar, F.; Raza, A.; Mohsin, S.M.; Mahmud, J.A.; Fujita, M.; Fotopoulos, V. Reactive Oxygen Species and Antioxidant Defense in Plants under Abiotic Stress: Revisiting the Crucial Role of a Universal Defense Regulator. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Z.; van Zanten, M.; Sasidharan, R. Mechanisms of plant acclimation to multiple abiotic stresses. Commun. Biol. 2025, 8, 655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Caparros, P.; De Filippis, L.; Gul, A.; Hasanuzzaman, M.; Ozturk, M.; Altay, V.; Lao, M.T. Oxidative stress and antioxidant metabolism under adverse environmental conditions: A review. Bot. Rev. 2021, 87, 421–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanuzzaman, M.; Bhuyan, M.H.M.B.; Anee, T.I.; Parvin, K.; Nahar, K.; Mahmud, J.A.; Fujita, M. Regulation of Ascorbate-Glutathione Pathway in Mitigating Oxidative Damage in Plants under Abiotic Stress. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Ling, L.; Wang, X.Q.; Cheng, T.; Wang, H.Y.; Ruan, Y.Y. Exogenous Hydrogen Sulfide and Methylglyoxal Alleviate Cadmium-Induced Oxidative Stress in Salix matsudana Koidz by Regulating Glutathione Metabolism. BMC Plant Biol. 2023, 23, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.Q.; Xin, J.P.; Zhao, C.; Tian, R. Role of Methylglyoxal and Glyoxalase in the Regulation of Plant Response to Heavy Metal Stress. Plant Cell Rep. 2024, 43, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z.; He, J.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Quinet, M.; Meng, Y. Exogenous melatonin enhances drought tolerance and germination in common buckwheat seeds through the coordinated effects of antioxidant and osmotic regulation. BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 613. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, A.L. Silicon: A valuable soil element for improving plant growth and CO2 sequestration. J. Adv. Res. 2025, 71, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.T.; Zan, T.X.; Li, K.K.; Hu, H.J.; Yang, T.Q.; Yin, J.L.; Zhu, Y.X. Silica Nanoparticles Promote the Germination of Salt-Stressed Pepper Seeds and Improve Growth and Yield of Field Pepper. Sci. Hortic. 2024, 337, 113570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.P.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Li, P.H.; Fu, Y.Y.; Li, S.; Gao, Y. Exogenous Application of Silica Nanoparticles Mitigates Combined Salt and Low-Temperature Stress in Cotton Seedlings by Improving the K+/Na+ Ratio and Antioxidant Defense. Plant Stress 2024, 14, 100597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, G.; Huang, Q.; Zhao, S.; Xu, Y.; He, Y.; Nikolic, M.; Nikolic, N.; Liang, Y.; Zhu, Z. Silicon nanoparticles in sustainable agriculture: Synthesis, absorption, and plant stress alleviation. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1393458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.X.; Xi, K.Y.; Ma, H.H.; Yang, P.H.; Wang, Y.H.; Li, H.L.; Yin, J.L.; Qin, M.L.; Liu, Y.Q. Exogenous Silica Nanoparticles Improve Drought Tolerance in Ginger by Modulating the Water Relationship. Environ. Sci. Nano 2024, 11, 1259–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahedi, S.M.; Moharrami, F.; Sarikhani, S.; Padervand, M. Selenium and Silica Nanostructure-Based Recovery of Strawberry Plants Subjected to Drought Stress. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 17672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Zhao, R.; Wang, D.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Q.; Wei, S.; Lu, F.; Peng, W.; Wu, C. Ginger (Zingiber officinale Rosc.) and its bioactive components are potential resources for health beneficial agents. Phytother Res. 2021, 35, 711–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Han, X.W.; Li, Y.T.; Guo, F.L.; Qi, C.D.; Liu, Y.Q.; Fang, S.Y.; Yin, J.L.; Zhu, Y.X. Genome-Wide Characterization and Function Analysis of Ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe) ZoGRFs in Responding to Adverse Stresses. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2024, 207, 108392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, F.M.; Zhang, S.Y.; Cao, B.L.; Xu, K. Low pH Alleviated Salinity Stress of Ginger Seedlings by Enhancing Photosynthesis, Fluorescence, and Mineral Element Contents. PeerJ 2021, 9, e10832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zieliński, J.; Tomaszewski, D.; Guzicka, M.; Maciejewska-Rutkowska, I. Stomata on the Pericarp of Species of the Genus Rosa L. (Rosaceae). Plant Syst. Evol. 2010, 284, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, S.; Kumari, N.; Sharma, V. Differential Response of Salt Stress on Brassica juncea: Photosynthetic Performance, Pigment, Proline, D1 and Antioxidant Enzymes. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2012, 54, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannopolitis, C.N.; Ries, S.K. Superoxide Dismutases: I. Occurrence in Higher Plants. Plant Physiol. 1977, 59, 309–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickel, K.S.; Cunningham, B.A. Improved Peroxidase Assay Method Using Leuco 2,3,6-Trichloroindophenol and Application to Comparative Measurements of Peroxidatic Catalysis. Anal. Biochem. 1969, 27, 292–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beers, R.F.; Sizer, I.W. A Spectrophotometric Method for Measuring the Breakdown of Hydrogen Peroxide by Catalase. J. Biol. Chem. 1952, 195, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakano, Y.; Asada, K. Hydrogen Peroxide Is Scavenged by Ascorbate-Specific Peroxidase in Spinach Chloroplasts. Plant Cell Physiol. 1981, 22, 867–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanuzzaman, M.; Hossain, M.A.; Fujita, M. Selenium-Induced Up-Regulation of the Antioxidant Defense and Methylglyoxal Detoxification System Reduces Salinity-Induced Damage in Rapeseed Seedlings. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2011, 143, 1704–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasanuzzaman, M.; Nahar, K.; Alam, M.M.; Fujita, M. Modulation of Antioxidant Machinery and the Methylglyoxal Detoxification System in Selenium-Supplemented Brassica napus Seedlings Confers Tolerance to High Temperature Stress. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2014, 161, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Jiang, X.; Zhang, J.; He, Y.; Zhu, X.; Zhou, X.; Gong, H.; Yin, J.; Liu, Y. Silicon Confers Cucumber Resistance to Salinity Stress through Regulation of Proline and Cytokinins. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2020, 156, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.M.; Ali, M.A.; Soliman, M.H.; Alqarawi, A.A.; Abd_Allah, E.F.; Fang, X.W. Insights into 28-Homobrassinolide (HBR)-Mediated Redox Homeostasis, AsA-GSH Cycle, and Methylglyoxal Detoxification in Soybean under Drought-Induced Oxidative Stress. J. Plant Interact. 2020, 15, 371–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wild, R.; Ooi, L.; Srikanth, V.; Münch, G. A Quick, Convenient and Economical Method for the Reliable Determination of Methylglyoxal in Millimolar Concentrations: The N-Acetyl-L-Cysteine Assay. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2012, 403, 2577–2581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Xu, X.; Hu, Y.; Han, W.; Yin, J.; Li, H.; Gong, H. Silicon Improves Salt Tolerance by Increasing Root Water Uptake in Cucumis sativus L. Plant Cell Rep. 2015, 34, 1629–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yao, H.J.; Wu, J.W.; Sun, H.; Gong, H.J. Silicon Improves Seed Germination and Alleviates Oxidative Stress of Bud Seedlings in Tomato under Water Deficit Stress. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2014, 78, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mokadem, A.Z.; Sheta, M.H.; Mancy, A.G.; Hussein, H.A.A.; Kenawy, S.K.M.; Sofy, A.R.; Abu-Shahba, M.S.; Mahdy, H.M.; Sofy, M.R.; Al-Bakry, A.F.; et al. Synergistic Effects of Kaolin and Silicon Nanoparticles for Ameliorating Deficit Irrigation Stress in Maize Plants by Upregulating Antioxidant Defense Systems. Plants 2023, 12, 2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutuliene, R.; Rageliene, L.; Samuoliene, G.; Brazaityte, A.; Urbutis, M.; Miliauskiene, J. The Response of Antioxidant System of Drought-Stressed Green Pea (Pisum sativum L.) Affected by Watering and Foliar Spray with Silica Nanoparticles. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanuzzaman, M.; Nahar, K.; Anee, T.I.; Fujita, M. Exogenous Silicon Attenuates Cadmium-Induced Oxidative Stress in Brassica napus L. by Modulating AsA-GSH Pathway and Glyoxalase System. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.J.; Lin, S.H.; Xu, P.L.; Wang, X.J.; Bai, J.G. Effects of Exogenous Silicon on the Activities of Antioxidant Enzymes and Lipid Peroxidation in Chilling-Stressed Cucumber Leaves. Agric. Sci. China 2009, 8, 1075–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, M.K.; Shobbar, Z.S.; Shahbazi, M.; Abedini, R.; Zare, S. Glutathione S-Transferase (GST) Family in Barley: Identification of Members, Enzyme Activity, and Gene Expression Pattern. J. Plant Physiol. 2013, 170, 1277–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, D.K.; Singh, S.; Singh, V.P.; Prasad, S.M.; Chauhan, D.K.; Dubey, N.K. Silicon Nanoparticles More Efficiently Alleviate Arsenate Toxicity than Silicon in Maize Cultivar and Hybrid Differing in Arsenate Tolerance. Front. Environ. Sci. 2016, 4, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, R.Z.; Wang, X.R.; Luo, Y.; Du, W.C.; Guo, H.Y.; Yin, D.Q. Effects of Soil Cadmium on Growth, Oxidative Stress and Antioxidant System in Wheat Seedlings (Triticum aestivum L.). Chemosphere 2007, 69, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, G.Z.; Li, G.Z.; Liu, G.Q.; Xu, W.; Peng, X.Q.; Wang, C.Y.; Zhu, Y.J.; Guo, T.C. Exogenous Salicylic Acid Enhances Wheat Drought Tolerance by Influence on the Expression of Genes Related to Ascorbate-Glutathione Cycle. Biol. Plant. 2013, 57, 718–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Xu, Z.C.; Lang, D.Y.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, W.J.; Zhang, X.H. Comprehensive Physiological, Transcriptomic, and Metabolomic Analyses Reveal the Synergistic Mechanism of Bacillus pumilus G5 Combined with Silicon Alleviate Oxidative Stress in Drought-Stressed Glycyrrhiza uralensis Fisch. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1033915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, R.K.; Pandey, P.; Rajpoot, R.; Rani, A.; Gautam, A.; Dubey, R.S. Exogenous Application of Calcium and Silica Alleviates Cadmium Toxicity by Suppressing Oxidative Damage in Rice Seedlings. Protoplasma 2015, 252, 959–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.H.; Zhou, Y.N.; Liang, X.G.; Jin, Y.K.; Xiao, Z.D.; Zhang, Y.J.; Huang, C.; Hong, B.; Chen, Z.Y.; Zhou, S.L.; et al. Exogenous Methylglyoxal Alleviates Drought-Induced ‘Plant Diabetes’ and Leaf Senescence in Maize. J. Exp. Bot. 2024, 75, 1982–1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaya, C.; Ugurlar, F.; Ashraf, M.; Alyemeni, M.N.; Ahmad, P. Exploring the Synergistic Effects of Melatonin and Salicylic Acid in Enhancing Drought Stress Tolerance in Tomato Plants through Fine-Tuning Oxidative-Nitrosative Processes and Methylglyoxal Metabolism. Sci. Hortic. 2023, 321, 112368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoque, T.S.; Hossain, M.A.; Mostofa, M.G.; Burritt, D.J.; Fujita, M.; Tran, L.P. Methylglyoxal: An Emerging Signaling Molecule in Plant Abiotic Stress Responses and Tolerance. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.G. Methylglyoxal and Glyoxalase System in Plants: Old Players, New Concepts. Bot. Rev. 2016, 82, 183–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sankaranarayanan, S.; Jamshed, M.; Kumar, A.; Skori, L.; Scandola, S.; Wang, T.N.; Spiegel, D.; Samuel, M.A. Glyoxalase Goes Green: The Expanding Roles of Glyoxalase in Plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossen, M.S.; Karim, M.F.; Fujita, M.; Bhuyan, M.H.M.B.; Nahar, K.; Masud, A.A.C.; Mahmud, J.A.; Hasanuzzaman, M. Comparative Physiology of Indica and Japonica Rice under Salinity and Drought Stress: An Intrinsic Study on Osmotic Adjustment, Oxidative Stress, Antioxidant Defense and Methylglyoxal Detoxification. Stresses 2022, 2, 156–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Q.L.; Zhang, Y.; Cheng, Y.X.; Tian, Y.L.; Luo, J.J.; Hu, Z.L.; Chen, G.P. The Role of Melatonin in Tomato Stress Response, Growth and Development. Plant Cell Rep. 2022, 41, 1631–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singla-Pareek, S.L.; Reddy, M.K.; Sopory, S.K. Genetic Engineering of the Glyoxalase Pathway in Tobacco Leads to Enhanced Salinity Tolerance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 14672–14677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.M.; Xiong, F.J.; Yu, X.H.; Gong, X.P.; Luo, J.T.; Jiang, Y.D.; Kuang, H.C.; Gao, B.J.; Niu, X.L.; Liu, Y.S. Overexpression of a Glyoxalase Gene, OsGly I, Improves Abiotic Stress Tolerance and Grain Yield in Rice (Oryza sativa L.). Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2016, 109, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sun, C.; Fang, S.; Yang, P.; Kyaw, H.W.W.; Liu, X.; Liu, Y.; Han, W.; Yin, J.; Qin, M.; Zhu, Y. Silica Nanoparticles Improve Drought Tolerance in Ginger by Modulating the AsA-GSH Pathway, the Glyoxalase System and Photosynthetic Metabolism. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 1467. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121467

Sun C, Fang S, Yang P, Kyaw HWW, Liu X, Liu Y, Han W, Yin J, Qin M, Zhu Y. Silica Nanoparticles Improve Drought Tolerance in Ginger by Modulating the AsA-GSH Pathway, the Glyoxalase System and Photosynthetic Metabolism. Horticulturae. 2025; 11(12):1467. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121467

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Chong, Shengyou Fang, Peihua Yang, Htet Wai Wai Kyaw, Xia Liu, Yiqing Liu, Weihua Han, Junliang Yin, Manli Qin, and Yongxing Zhu. 2025. "Silica Nanoparticles Improve Drought Tolerance in Ginger by Modulating the AsA-GSH Pathway, the Glyoxalase System and Photosynthetic Metabolism" Horticulturae 11, no. 12: 1467. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121467

APA StyleSun, C., Fang, S., Yang, P., Kyaw, H. W. W., Liu, X., Liu, Y., Han, W., Yin, J., Qin, M., & Zhu, Y. (2025). Silica Nanoparticles Improve Drought Tolerance in Ginger by Modulating the AsA-GSH Pathway, the Glyoxalase System and Photosynthetic Metabolism. Horticulturae, 11(12), 1467. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121467