Cultivar-Specific Responses of Camelina (Camelina sativa (L.) Crantz) Sprouts and Microgreens to UV-B Radiation: Effects on Germination, Growth, Biochemical Traits, and Stress-Related Parameters

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material and UV-B Treatment

2.2. Germination Test and Measurements of Germination Parameters

2.3. Biomass and Biometric Measurements

2.4. Extraction and Quantification of Total Phenolics, Flavonoids, and Antioxidant Activity

2.5. Extraction and Quantification of Chlorophylls and Carotenoids

2.6. Extraction and Determination of Glucosinolates

2.7. Evaluation of Lipid Peroxidation by MDA Assay

2.8. Extraction and Quantification of Proline

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Germination Test and Measurements of Germination Parameters

3.2. Biometric Parameters and Biomass Productivity

3.2.1. Sprouts

3.2.2. Microgreens

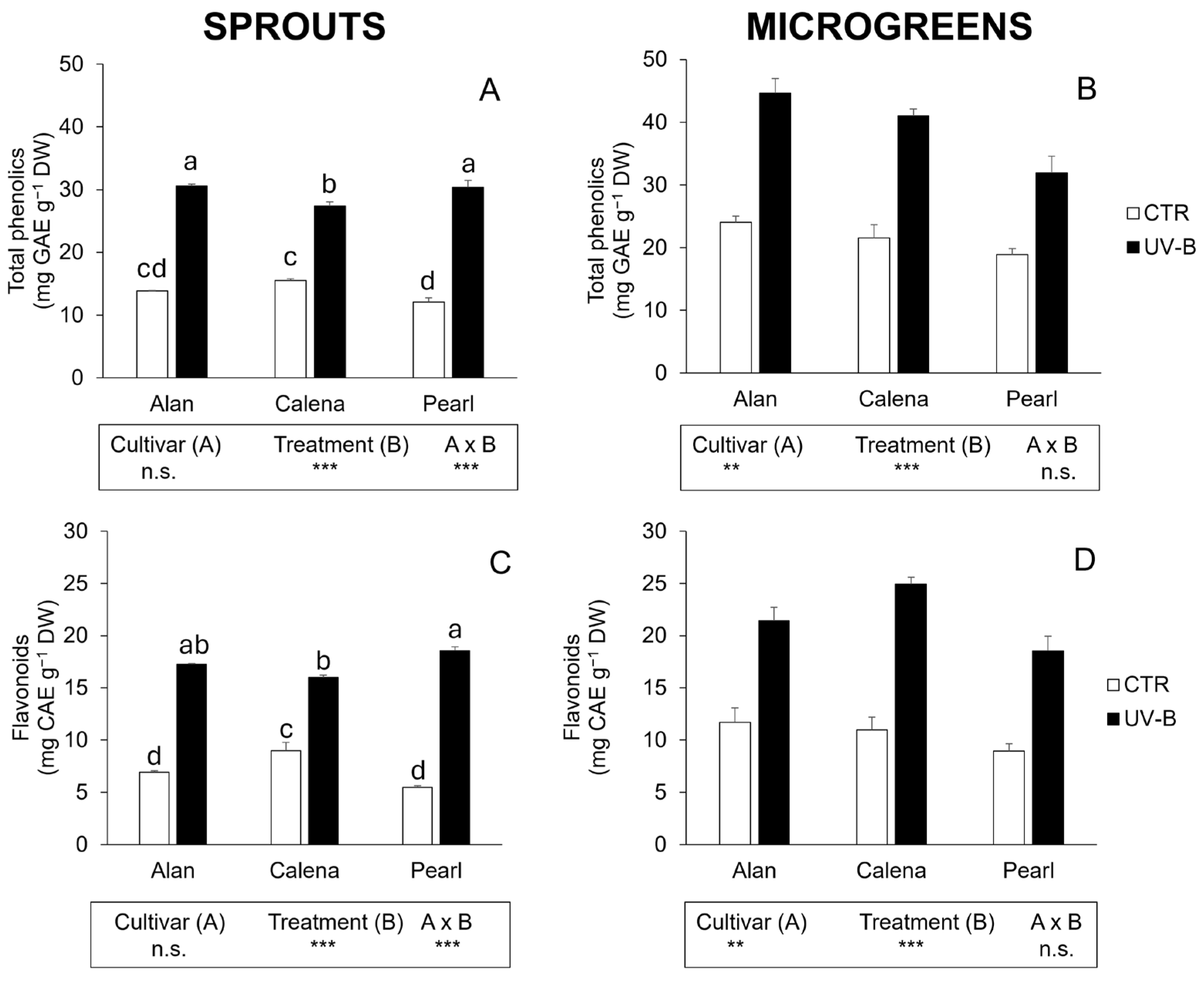

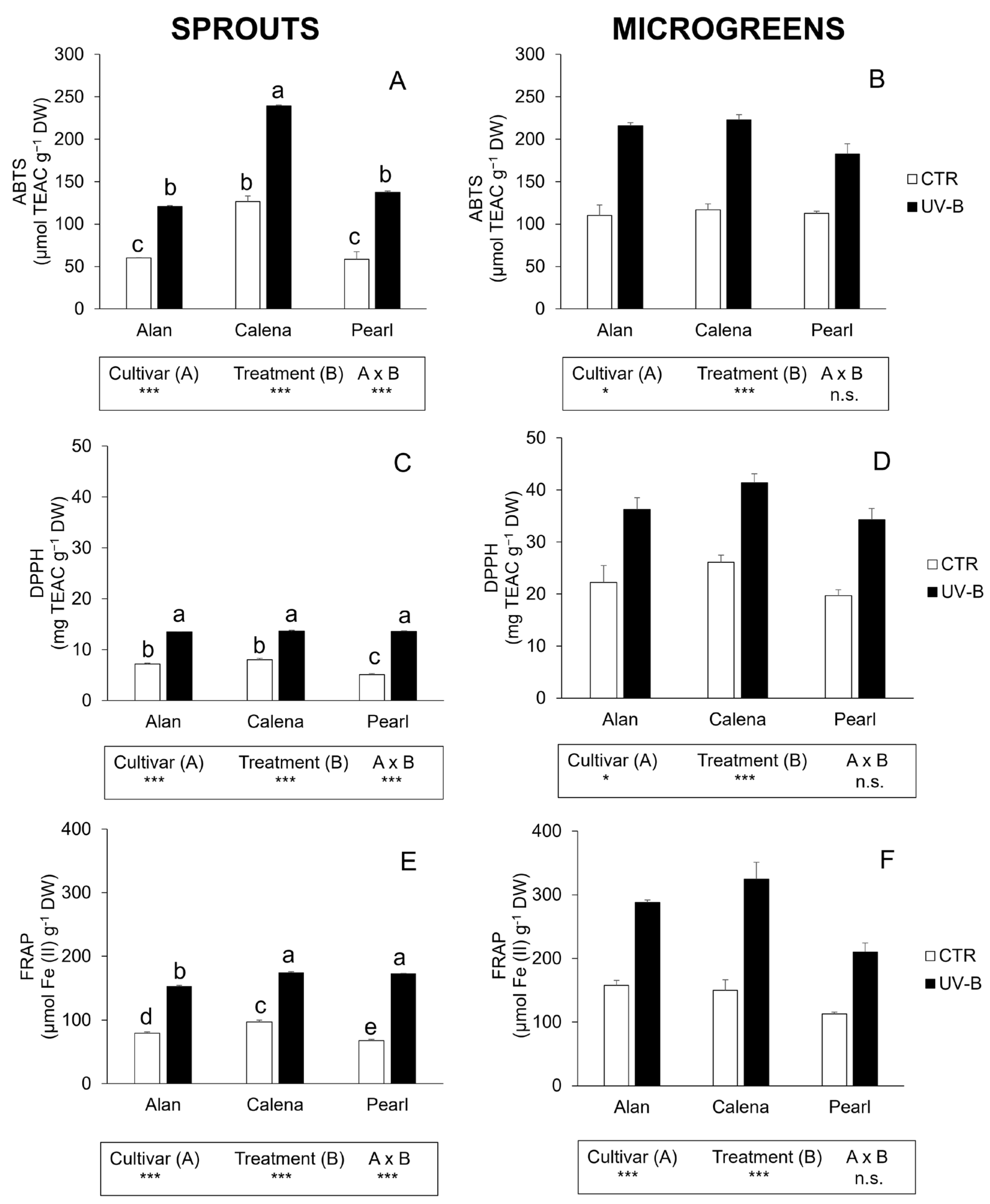

3.3. Total Phenolics, Flavonoids, and Antioxidant Activity

3.3.1. Sprouts

3.3.2. Microgreens

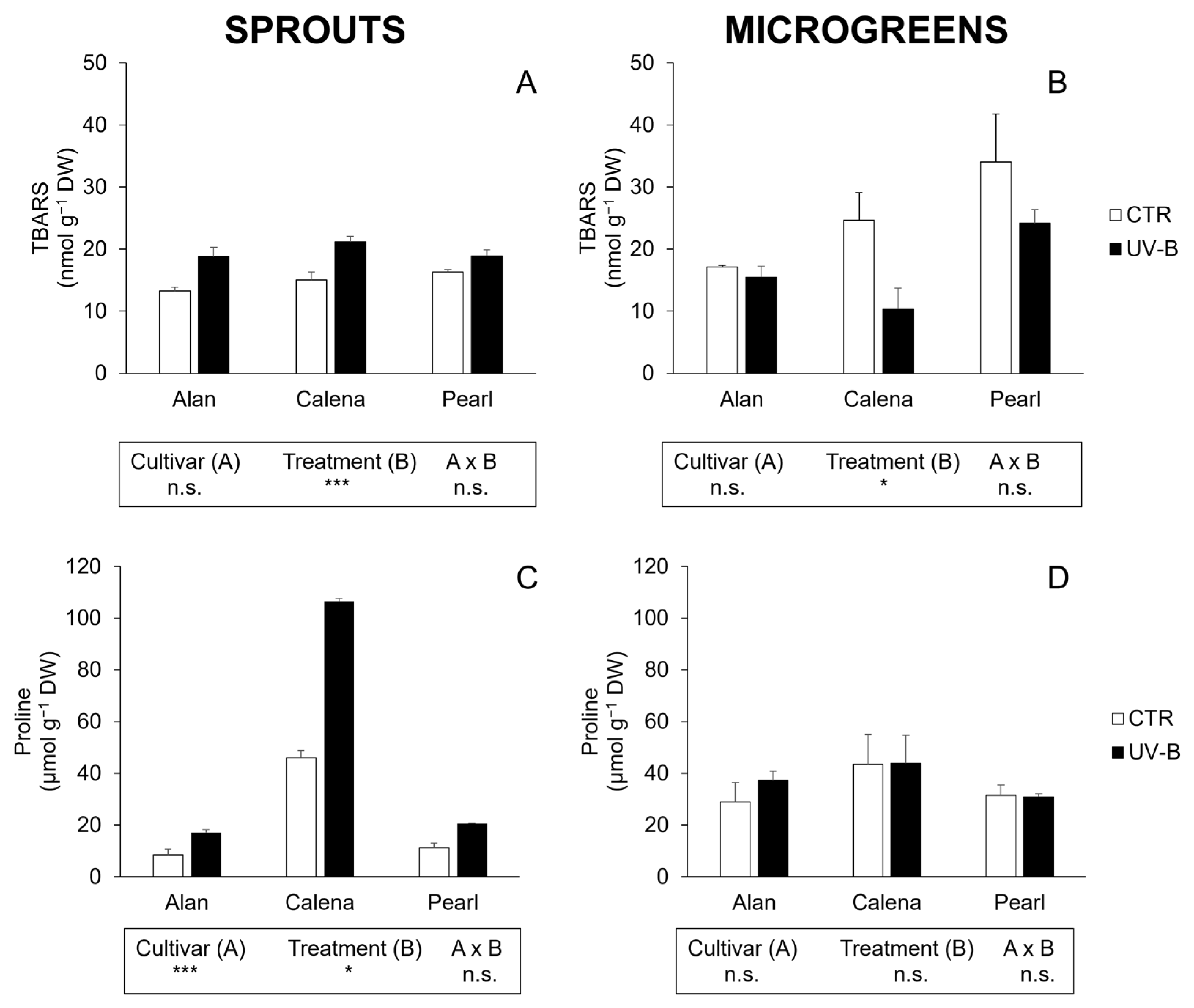

3.4. Lipid Peroxidation (TBARS) and Proline

3.4.1. Sprouts

3.4.2. Microgreens

3.5. Chlorophylls and Carotenoids

3.5.1. Sprouts

3.5.2. Microgreens

3.6. Individual and Total Glucosinolates

- The GLS9 content showed significant decreases in the ‘Alan’ and ‘Calena’ cultivars under UV-B treatment, with reductions of 15.1% and 18.4%, respectively.

- The GLS10 concentration displayed variable responses: ‘Alan’ and ‘Pearl’ were not affected by the UV-B treatment, whereas ‘Calena’ showed a significant 13.9% decrease when sprouts were irradiated with UV-B.

- The GLS11 content showed no significant changes after the UV-B exposure in any of the cultivars studied, although the lowest GLS11 levels were detected in ‘Pearl’ compared to both ‘Alan’ and ‘Calena’.

| Cultivar | Treatment | GLS9 | GLS10 | GLS11 | Total GLSs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alan | CTR | 2.12 ± 0.06 b | 5.38 ± 0.12 a | 0.97 ± 0.01 ab | 8.47 ± 0.19 a |

| UV-B | 1.80 ± 0.02 c | 5.03 ± 0.12 a | 1.03 ± 0.01 a | 7.86 ± 0.15 a | |

| Calena | CTR | 1.74 ± 0.02 c | 5.03 ± 0.11 a | 0.99 ± 0.02 ab | 7.76 ± 0.15 a |

| UV-B | 1.42 ± 0.08 d | 4.33 ± 0.22 b | 0.90 ± 0.05 b | 6.65 ± 0.34 b | |

| Pearl | CTR | 2.31 ± 0.04 ab | 4.98 ± 0.14 ab | 0.70 ± 0.02 c | 7.99 ± 0.19 a |

| UV-B | 2.47 ± 0.06 a | 5.23 ± 0.08 a | 0.71 ± 0.01 c | 8.41 ± 0.13 a | |

| Mean effect | |||||

| Alan | 1.96 ± 0.08 b | 5.20 ± 0.11 a | 1.00 ± 0.01 a | 8.16 ± 0.17 a | |

| Calena | 1.58 ± 0.08 c | 4.68 ± 0.19 b | 0.95 ± 0.03 a | 7.20 ± 0.30 b | |

| Pearl | 2.39 ± 0.05 a | 5.11 ± 0.09 a | 0.71 ± 0.01 b | 8.20 ± 0.14 a | |

| CTR | 2.05 ± 0.09 a | 5.13 ± 0.09 a | 0.89 ± 0.05 | 8.07 ± 0.14 a | |

| UV-B | 1.90 ± 0.16 b | 4.86 ± 0.16 b | 0.88 ± 0.05 | 7.64 ± 0.28 b | |

| ANOVA | |||||

| Cultivar (A) | *** | ** | *** | *** | |

| Treatment (B) | ** | * | n.s. | * | |

| A × B | *** | * | * | ** | |

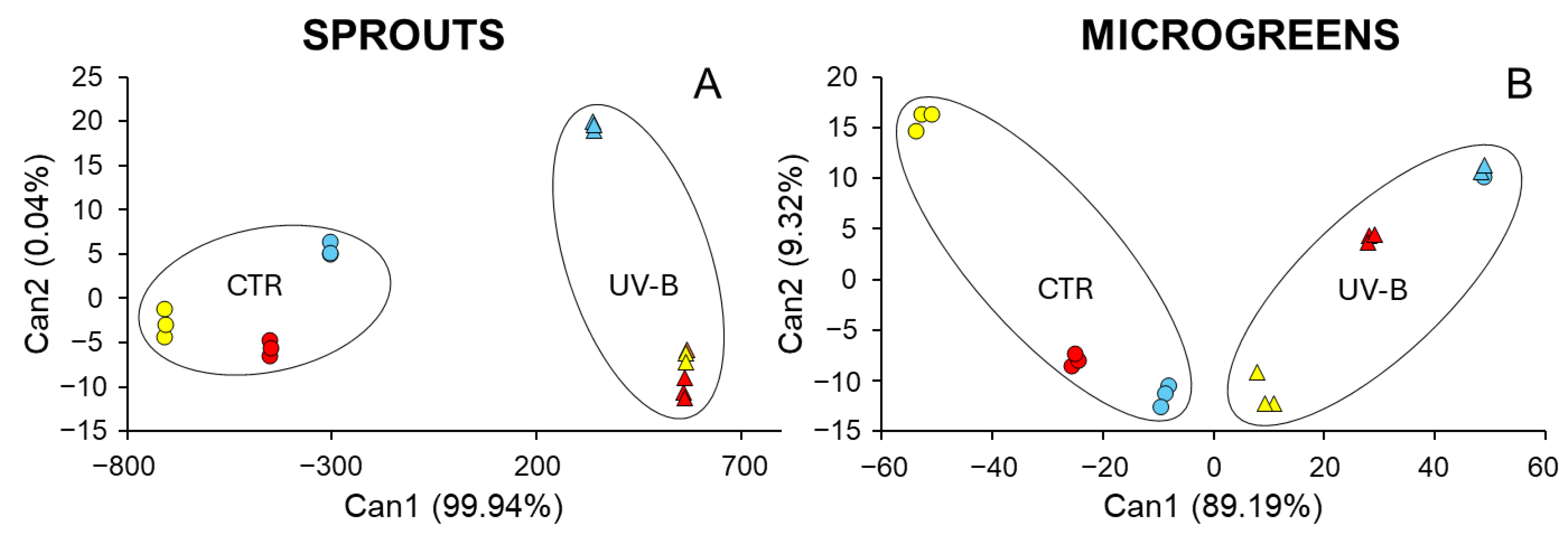

3.7. Canonical Discriminant Analysis (CDA) and Pearson’s Correlation

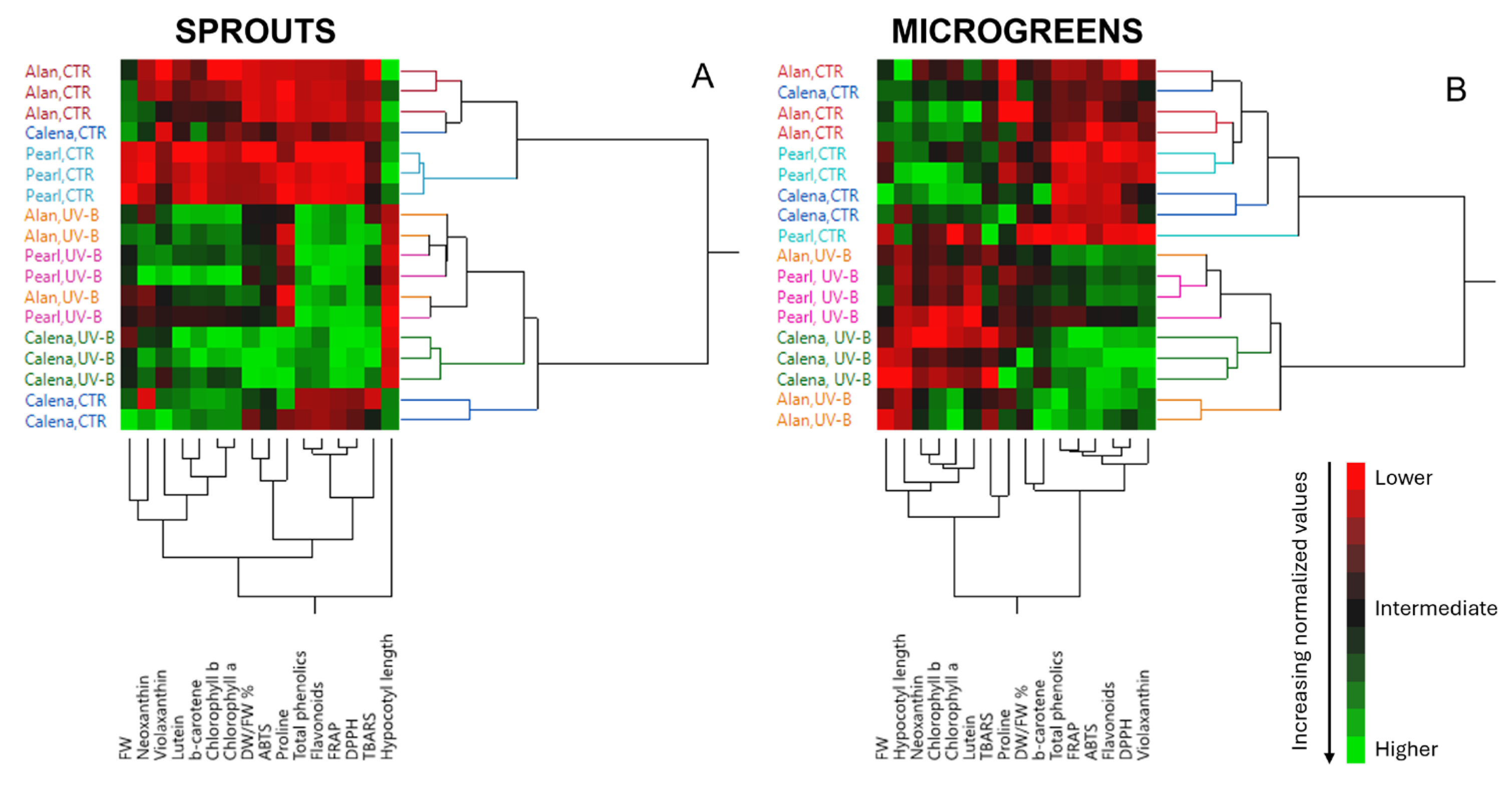

3.8. Hierarchical Clustering Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ABTS | 2,2′-azinobis-(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulphonic acid) (antioxidant assay) |

| ANOVA | Analysis of variance |

| CAE | Catechin equivalents (for total flavonoids) |

| CDA | Canonical Discriminant Analysis |

| CTR | Control (untreated condition) |

| DPPH | 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (free radical; antioxidant assay |

| DW | Dry weight |

| DW/FW | Dry weight to fresh weight ratio |

| EC | Electrical conductivity |

| FW | Fresh weight |

| FW/DW | Fresh weight to dry weight ratio |

| FRAP | Ferric Reducing Antioxidant Power (antioxidant assay) |

| GAE | Gallic acid equivalents (for total phenolics |

| GLS | Glucosinolates |

| GLS9 | Glucoarabin (9-(methylsulfinyl)nonylglucosinolate) |

| GLS10 | Glucocamelinin (10-(methylsulfinyl)decylglucosinolate) |

| GLS11 | Homoglucocamelinin (11-(methylsulfinyl)undecylglucosinolate) |

| HCA | Hierarchical clustering analysis |

| HPLC | High-performance liquid chromatography |

| LED/LEDs | Light-emitting diode(s) |

| MDA | Malondialdehyde (lipid peroxidation marker) |

| MGT | Mean germination time |

| ODS | Octadecylsilane (C18) stationary phase |

| PAR | Photosynthetically active radiation |

| PPFD | Photosynthetic photon flux density |

| SE | Standard error |

| TBARS | Thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (lipid peroxidation assay) |

| TBA | Thiobarbituric acid |

| TCA | Trichloroacetic acid |

| TEAC | Trolox equivalent antioxidant capacity |

| UV-A | Ultraviolet-A (315–400 nm) |

| UV-B | Ultraviolet-B (280–320 nm) |

| UVR8 | UV RESISTANCE LOCUS 8 (UV-B photoreceptor) |

References

- Mondor, M.; Hernández-Álvarez, A.J. Camelina Sativa Composition, Attributes, and Applications: A Review. Euro J. Lipid Sci. Tech. 2022, 124, 2100035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sydor, M.; Kurasiak-Popowska, D.; Stuper-Szablewska, K.; Rogoziński, T. Camelina Sativa. Status Quo and Future Perspectives. Ind. Crops Prod. 2022, 187, 115531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelini, L.G.; Abou Chehade, L.; Foschi, L.; Tavarini, S. Performance and Potentiality of Camelina (Camelina Sativa L. Crantz) Genotypes in Response to Sowing Date under Mediterranean Environment. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanetti, F.; Alberghini, B.; Marjanović Jeromela, A.; Grahovac, N.; Rajković, D.; Kiprovski, B.; Monti, A. Camelina, an Ancient Oilseed Crop Actively Contributing to the Rural Renaissance in Europe. A Review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 41, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemente, C.; Rossi, A.; Angelini, L.G.; Villalba, R.G.; Moreno, D.A.; Tomás-Barberán, F.A.; Tavarini, S. Effect of Environmental Conditions on Seed Yield and Metabolomic Profile of Camelina (Camelina Sativa (L.) Crantz) through on Farm Multilocation Trials. J. Agric. Food Res. 2025, 21, 101814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravi, E.; Falcinelli, B.; Mallia, G.; Marconi, O.; Royo-Esnal, A.; Benincasa, P. Effect of Sprouting on the Phenolic Compounds, Glucosinolates, and Antioxidant Activity of Five Camelina Sativa (L.) Crantz Cultivars. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebert, A.W.; Wu, T.H.; Yang, R.Y. Amaranth Sprouts and Microgreens–a Homestead Vegetable Production Option to Enhance Food and Nutrition Security in the Rural-Urban Continuum. In Proceedings of the Regional Symposium on Sustaining Small-Scale Vegetable Production and Marketing Systems for Food and Nutrition Security (SEAVEG2014), Bangkok, Thailand, 25–27 February 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galieni, A.; Falcinelli, B.; Stagnari, F.; Datti, A.; Benincasa, P. Sprouts and Microgreens: Trends, Opportunities, and Horizons for Novel Research. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapusta-Duch, J.; Smoleń, S.; Jędrszczyk, E.; Leszczyńska, T.; Borczak, B. Basic Composition, Antioxidative Properties, and Selected Mineral Content of the Young Shoots of Nigella (Nigella Sativa L.), Safflower (Carthamus Tinctorius L.), and Camelina (Camelina Sativa L.) at Different Stages of Vegetation. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santin, M.; Ranieri, A.; Castagna, A. Anything New under the Sun? An Update on Modulation of Bioactive Compounds by Different Wavelengths in Agricultural Plants. Plants 2021, 10, 1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Dong, Y.; Huang, X. Plant Responses to UV-B Radiation: Signaling, Acclimation and Stress Tolerance. Stress Biol. 2022, 2, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, G.I. The UV-B Photoreceptor UVR8: From Structure to Physiology. Plant Cell 2014, 26, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizzini, L.; Favory, J.-J.; Cloix, C.; Faggionato, D.; O’Hara, A.; Kaiserli, E.; Baumeister, R.; Schäfer, E.; Nagy, F.; Jenkins, G.I.; et al. Perception of UV-B by the Arabidopsis UVR8 Protein. Science 2011, 332, 103–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, D.; Hu, Q.; Yan, Z.; Chen, W.; Yan, C.; Huang, X.; Zhang, J.; Yang, P.; Deng, H.; Wang, J.; et al. Structural Basis of Ultraviolet-B Perception by UVR8. Nature 2012, 484, 214–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, C.; Liu, H. How Plants Protect Themselves from Ultraviolet-B Radiation Stress. Plant Physiol. 2021, 187, 1096–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, D.; Agrawal, M.; Agrawal, S.B. Dose Differentiation in Elevated UV-B Manifests Variable Response of Carbon–Nitrogen Content with Changes in Secondary Metabolites of Curcuma Caesia Roxb. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 72871–72885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, A.; Agrawal, M.; Agrawal, S.B. Ultraviolet-B Induced Modifications in Growth, Physiology, Essential Oil Content and Composition of a Medicinal Herbal Plant Psoralea Corylifolia. Hortic. Environ. Biotechnol. 2022, 63, 917–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, K.; Agrawal, S.B. Effects of Elevated Ultraviolet-B on the Floral and Leaf Characteristics of a Medicinal Plant Wedelia Chinensis (Osbeck) Merr. along with Essential Oil Contents. Trop. Ecol. 2023, 64, 307–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, K.; Agrawal, S.B. An Assessment of Dose-Dependent UV-B Sensitivity in Eclipta Alba: Biochemical Traits, Antioxidative Properties, and Wedelolactone Yield. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 45434–45449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, B.A.; Cloix, C.; Jiang, G.H.; Kaiserli, E.; Herzyk, P.; Kliebenstein, D.J.; Jenkins, G.I. A UV-B-Specific Signaling Component Orchestrates Plant UV Protection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 18225–18230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favory, J.-J.; Stec, A.; Gruber, H.; Rizzini, L.; Oravecz, A.; Funk, M.; Albert, A.; Cloix, C.; Jenkins, G.I.; Oakeley, E.J.; et al. Interaction of COP1 and UVR8 Regulates UV-B-Induced Photomorphogenesis and Stress Acclimation in Arabidopsis. EMBO J. 2009, 28, 591–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takshak, S.; Agrawal, S.B. Defense Potential of Secondary Metabolites in Medicinal Plants under UV-B Stress. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2019, 193, 51–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santin, M.; Lucini, L.; Castagna, A.; Rocchetti, G.; Hauser, M.-T.; Ranieri, A. Comparative “Phenol-Omics” and Gene Expression Analyses in Peach (Prunus Persica) Skin in Response to Different Postharvest UV-B Treatments. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2019, 135, 511–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graßmann, J. Terpenoids as Plant Antioxidants. In Vitamins & Hormones; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2005; Volume 72, pp. 505–535. ISBN 978-0-12-709872-2. [Google Scholar]

- Dincheva, I.; Badjakov, I.; Galunska, B. New Insights into the Research of Bioactive Compounds from Plant Origins with Nutraceutical and Pharmaceutical Potential. Plants 2023, 12, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caleja, C.; Ribeiro, A.; Barreiro, M.F.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R. Phenolic Compounds as Nutraceuticals or Functional Food Ingredients. CPD 2017, 23, 2787–2806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schreiner, M.; Mewis, I.; Huyskens-Keil, S.; Jansen, M.A.K.; Zrenner, R.; Winkler, J.B.; O’Brien, N.; Krumbein, A. UV-B-Induced Secondary Plant Metabolites-Potential Benefits for Plant and Human Health. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 2012, 31, 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traka, M.H. Health Benefits of Glucosinolates. In Advances in Botanical Research; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; Volume 80, pp. 247–279. ISBN 978-0-08-100327-5. [Google Scholar]

- Ulm, R.; Jenkins, G.I. Q&A: How Do Plants Sense and Respond to UV-B Radiation? BMC Biol. 2015, 13, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brazaitytė, A.; Sakalauskienė, S.; Samuolienė, G.; Jankauskienė, J.; Viršilė, A.; Novičkovas, A.; Sirtautas, R.; Miliauskienė, J.; Vaštakaitė, V.; Dabašinskas, L.; et al. The Effects of LED Illumination Spectra and Intensity on Carotenoid Content in Brassicaceae Microgreens. Food Chem. 2015, 173, 600–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brazaitytė, A.; Miliauskienė, J.; Vaštakaitė-Kairienė, V.; Sutulienė, R.; Laužikė, K.; Duchovskis, P.; Małek, S. Effect of Different Ratios of Blue and Red LED Light on Brassicaceae Microgreens under a Controlled Environment. Plants 2021, 10, 801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasibi, F.; M-Kalantari, K. The Effects Of Uv-A, Uv-B And Uv-C On Protein And Ascorbate Content, Lipid Peroxidation and Biosynthesis of Screening Compounds in Brassica napus. Trans. A Sci. 2005, 29, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neugart, S.; Majer, P.; Schreiner, M.; Hideg, É. Blue Light Treatment but Not Green Light Treatment After Pre-Exposure to UV-B Stabilizes Flavonoid Glycoside Changes and Corresponding Biological Effects in Three Different Brassicaceae Sprouts. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 11, 611247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, L.C.; Veit, M.; Weissenböck, G.; Bornman, J.F. Differential Flavonoid Response to Enhanced UV-B Radiation in Brassica Napus. Phytochemistry 1998, 49, 1021–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuolienė, G.; Brazaitytė, A.; Viršilė, A.; Miliauskienė, J.; Vaštakaitė-Kairienė, V.; Duchovskis, P. Nutrient Levels in Brassicaceae Microgreens Increase Under Tailored Light-Emitting Diode Spectra. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISTA. Germination Test, 2015th ed.; ISTA: Bassersdorf, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Santin, M.; Parichanon, P.; Sciampagna, M.C.; Ranieri, A.; Castagna, A. Enhancing Tomato Productivity and Quality in Moderately Saline Soils through Salicornia-Assisted Cultivation Methods: A Comparative Study. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso Borbalán, Á.M.; Zorro, L.; Guillén, D.A.; García Barroso, C. Study of the Polyphenol Content of Red and White Grape Varieties by Liquid Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry and Its Relationship to Antioxidant Power. J. Chromatogr. A 2003, 1012, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.-O.; Chun, O.K.; Kim, Y.J.; Moon, H.-Y.; Lee, C.Y. Quantification of Polyphenolics and Their Antioxidant Capacity in Fresh Plums. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 6509–6515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Re, R.; Pellegrini, N.; Proteggente, A.; Pannala, A.; Yang, M.; Rice-Evans, C. Antioxidant Activity Applying an Improved ABTS Radical Cation Decolorization Assay. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 1999, 26, 1231–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzie, I.F.F.; Strain, J.J. The Ferric Reducing Ability of Plasma (FRAP) as a Measure of “Antioxidant Power”: The FRAP Assay. Anal. Biochem. 1996, 239, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulcin, İ.; Alwasel, S.H. DPPH Radical Scavenging Assay. Processes 2023, 11, 2248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santin, M.; Sciampagna, M.C.; Mannucci, A.; Puccinelli, M.; Angelini, L.G.; Tavarini, S.; Accorsi, M.; Incrocci, L.; Ranieri, A.; Castagna, A. Supplemental UV-B Exposure Influences the Biomass and the Content of Bioactive Compounds in Linum Usitatissimum L. Sprouts and Microgreens. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozzo, S.; Piergiovanni, A.R.; Ponzoni, E.; Brambilla, I.M.; Galasso, I. Evaluation of Nutritional and Antinutritional Compounds in a Collection of Camelina Sativa Varieties. J. Crop Improv. 2023, 37, 934–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, R.; Galasso, I.; Reggiani, R. Variability in Glucosinolate Content among Camelina Species. AJPS 2014, 05, 294–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draper, H.H.; Hadley, M. [43] Malondialdehyde Determination as Index of Lipid Peroxidation. In Methods in Enzymology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1990; Volume 186, pp. 421–431. ISBN 978-0-12-182087-9. [Google Scholar]

- Kosugi, H.; Kikugawa, K. Thiobarbituric Acid Reaction of Aldehydes and Oxidized Lipids in Glacial Acetic Acid. Lipids 1985, 20, 915–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, L.S.; Waldren, R.P.; Teare, I.D. Rapid Determination of Free Proline for Water-Stress Studies. Plant Soil. 1973, 39, 205–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugimoto, K. Seed Germination Under UV-B Irradiation; Minami Kyushu University: Miyazaki, Japan, 2013; Volume 43. [Google Scholar]

- Begum, H.A.; Hamayun, M.; Shad, N.; Khan, W.; Ahmad, J.; Khan, M.E.H.; Jones, D.A.; Ali, K. Effects of UV Radiation on Germination, Growth, Chlorophyll Content, and Fresh and Dry Weights of Brassica Rapa L. and Eruca Sativa L. Sarhad J. Agric. 2021, 37, 1016–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.L.; Yeom, M.-S.; Sim, H.-S.; Lee, G.O.; Kang, I.-J.; Yang, G.-S.; Yun, J.G.; Son, K.-H. Effect of Pre-Harvest Intermittent UV-B Exposure on Growth and Secondary Metabolites in Achyranthes Japonica Nakai Microgreens in a Vertical Farm. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, J.H.; Teramura, A.H.; Ziska, L.H. Variation in UV-B Sensitivity in Plants from a 3,000-m Elevational Gradient in Hawaii. Am. J. Bot. 1992, 79, 737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skowron, E.; Trojak, M.; Pacak, I.; Węzigowska, P.; Szymkiewicz, J. Enhancing the Quality of Indoor-Grown Basil Microgreens with Low-Dose UV-B or UV-C Light Supplementation. IJMS 2025, 26, 2352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaštakaitė, V.; Viršilė, A.; Brazaitytė, A.; Samuolienė, G.; Jankauskienė, J.; Novičkovas, A.; Duchovskis, P. Pulsed Light-Emitting Diodes for a Higher Phytochemical Level in Microgreens. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 65, 6529–6534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Huang, Y.; Liu, G.; Qin, F.; Yang, S.; Xu, X. Effects of Enhanced UV-B Radiation on Morphology, Physiology, Biomass, Leaf Anatomy and Ultrastructure in Male and Female Mulberry (Morus Alba) Saplings. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2016, 129, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajabbeigi, E.; Eichholz, I.; Beesk, N.; Ulrichs, C.; Kroh, L.W.; Rohn, S.; Huyskens-Keil, S. Interaction of Drought Stress and UV-B Radiation-Impact on Biomass Production and Flavonoid Metabolism in Lettuce (Lactuca Sativa L.). J. Appl. Bot. Food Qual. 2013, 86, 190–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Kumari, R.; Agrawal, M.; Agrawal, S.B. Modification in Growth, Biomass and Yield of Radish under Supplemental UV-B at Different NPK Levels. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2011, 74, 897–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barańska, D.; Panek, J.; Różalska, S.; Turnau, K.; Frąc, M. Microgreens as the Future of Urban Horticulture and Superfoods, Supported by Post-Harvest Innovations for Shelf-Life Increase: A Review. Sci. Hortic. 2025, 350, 114303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biever, J.J.; Brinkman, D.; Gardner, G. UV-B Inhibition of Hypocotyl Growth in Etiolated Arabidopsis Thaliana Seedlings Is a Consequence of Cell Cycle Arrest Initiated by Photodimer Accumulation. J. Exp. Bot. 2014, 65, 2949–2961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, M.; Rosenqvist, E.; Prinsen, E.; Pescheck, F.; Flygare, A.-M.; Kalbina, I.; Jansen, M.A.K.; Strid, Å. Downsizing in Plants—UV Light Induces Pronounced Morphological Changes in the Absence of Stress. Plant Physiol. 2021, 187, 378–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, M.; Kalbina, I.; Rosenqvist, E.; Jansen, M.A.K.; Strid, Å. Supplementary UV-A and UV-B Radiation Differentially Regulate Morphology in Ocimum Basilicum. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2023, 22, 2219–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heijde, M.; Ulm, R. UV-B Photoreceptor-Mediated Signalling in Plants. Trends Plant Sci. 2012, 17, 230–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stracke, R.; Favory, J.-J.; Gruber, H.; Bartelniewoehner, L.; Bartels, S.; Binkert, M.; Funk, M.; Weisshaar, B.; Ulm, R. The Arabidopsis bZIP Transcription Factor HY5 Regulates Expression of the PFG1/MYB12 Gene in Response to Light and Ultraviolet-B Radiation. Plant Cell Environ. 2010, 33, 88–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuntini, D.; Lazzeri, V.; Calvenzani, V.; Dall’Asta, C.; Galaverna, G.; Tonelli, C.; Petroni, K.; Ranieri, A. Flavonoid Profiling and Biosynthetic Gene Expression in Flesh and Peel of Two Tomato Genotypes Grown under UV-B-Depleted Conditions during Ripening. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 5905–5915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, K.; Shui, S.; Yan, L.; Liu, C.; Zheng, L. Effect of Postharvest UV-B or UV-C Irradiation on Phenolic Compounds and Their Transcription of Phenolic Biosynthetic Genes of Table Grapes. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 55, 3292–3302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ubi, B.E.; Honda, C.; Bessho, H.; Kondo, S.; Wada, M.; Kobayashi, S.; Moriguchi, T. Expression Analysis of Anthocyanin Biosynthetic Genes in Apple Skin: Effect of UV-B and Temperature. Plant Sci. 2006, 170, 571–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Zamora, L.; Castillejo, N.; Artés-Hernández, F. Postharvest UV-B and Photoperiod with Blue + Red LEDs as Strategies to Stimulate Carotenogenesis in Bell Peppers. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 3736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillejo, N.; Martínez-Zamora, L.; Artés-Hernández, F. Periodical UV-B Radiation Hormesis in Biosynthesis of Kale Sprouts Nutraceuticals. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2021, 165, 274–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloix, C.; Kaiserli, E.; Heilmann, M.; Baxter, K.J.; Brown, B.A.; O’Hara, A.; Smith, B.O.; Christie, J.M.; Jenkins, G.I. C-Terminal Region of the UV-B Photoreceptor UVR8 Initiates Signaling through Interaction with the COP1 Protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 16366–16370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czégény, G.; Mátai, A.; Hideg, É. UV-B Effects on Leaves—Oxidative Stress and Acclimation in Controlled Environments. Plant Sci. 2016, 248, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hideg, É.; Jansen, M.A.K.; Strid, Å. UV-B Exposure, ROS, and Stress: Inseparable Companions or Loosely Linked Associates? Trends Plant Sci. 2013, 18, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agathokleous, E.; Calabrese, E.J.; Barceló, D. Environmental Hormesis: New Developments. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 906, 167450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erofeeva, E.A. Environmental Hormesis of Non-Specific and Specific Adaptive Mechanisms in Plants. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 804, 150059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klem, K.; Holub, P.; Štroch, M.; Nezval, J.; Špunda, V.; Tříska, J.; Jansen, M.A.K.; Robson, T.M.; Urban, O. Ultraviolet and Photosynthetically Active Radiation Can Both Induce Photoprotective Capacity Allowing Barley to Overcome High Radiation Stress. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2015, 93, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moustakas, M.; Moustaka, J.; Sperdouli, I. Hormesis in Photosystem II: A Mechanistic Understanding. Curr. Opin. Toxicol. 2022, 29, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkova, P.Y.; Bondarenko, E.V.; Kazakova, E.A. Radiation Hormesis in Plants. Curr. Opin. Toxicol. 2022, 30, 100334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salama, H.M.H.; Al Watban, A.A.; Al-Fughom, A.T. Effect of Ultraviolet Radiation on Chlorophyll, Carotenoid, Protein and Proline Contents of Some Annual Desert Plants. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2011, 18, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Huang, X.; Deng, X.W. The Photomorphogenic Central Repressor COP1: Conservation and Functional Diversification during Evolution. Plant Commun. 2020, 1, 100044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, J.C.; Appel, H.M.; Ferrieri, A.P.; Arnold, T.M. Flexible Resource Allocation during Plant Defense Responses. Front. Plant Sci. 2013, 4, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchar, V.A.; Robberecht, R. Integration and Scaling of UV-B Radiation Effects on Plants: From Molecular Interactions to Whole Plant Responses. Ecol. Evol. 2016, 6, 4866–4884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czerniawski, P.; Piasecka, A.; Bednarek, P. Evolutionary Changes in the Glucosinolate Biosynthetic Capacity in Species Representing Capsella, Camelina and Neslia Genera. Phytochemistry 2021, 181, 112571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galasso, I.; Piergiovanni, A.R.; Ponzoni, E.; Brambilla, I.M. Spectrophotometric Determination of Total Glucosinolate Content in Different Tissues of Camelina Sativa (L.) Crantz. Food Anal. Methods 2025, 18, 376–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte-Sierra, A.; Munzoor Hasan, S.M.; Angers, P.; Arul, J. UV-B Radiation Hormesis in Broccoli Florets: Glucosinolates and Hydroxy-Cinnamates Are Enhanced by UV-B in Florets during Storage. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2020, 168, 111278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira-Rodríguez, M.; Nair, V.; Benavides, J.; Cisneros-Zevallos, L.; Jacobo-Velázquez, D. UVA, UVB Light Doses and Harvesting Time Differentially Tailor Glucosinolate and Phenolic Profiles in Broccoli Sprouts. Molecules 2017, 22, 1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Wang, J.; Yang, Y.; Li, Z.; Mustafa, G.; Li, Y.; Liu, L.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Q. UV-B Irradiation Enhances the Accumulation of Beneficial Glucosinolates Induced by Melatonin in Chinese Kale Sprout. Hortic. Plant J. 2024, 10, 995–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Dong, W.; Yang, T.; Luo, Y.; Chen, P. Preharvest UVB application increases glucosinolate contents and enhances postharvest quality of broccoli microgreens. Molecules 2021, 26, 3247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Murad, M.; Razi, K.; Jeong, B.R.; Samy, P.M.A.; Muneer, S. Light Emitting Diodes (LEDs) as Agricultural Lighting: Impact and Its Potential on Improving Physiology, Flowering, and Secondary Metabolites of Crops. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcel, M.M.; Lin, X.; Huang, J.; Wu, J.; Zheng, S. The Application of LED Illumination and Intelligent Control in Plant Factory, a New Direction for Modern Agriculture: A Review. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 1732, 012178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Time (min) | Solvent A 1 (%) | Solvent B 1 (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 100 | 0 |

| 8 | 100 | 0 |

| 10 | 0 | 100 |

| 26 | 0 | 100 |

| 28 | 100 | 0 |

| 32 | 100 | 0 |

| Cultivar | Treatment | Germination (%) | MGT (Day) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alan | CTR | 88.0 ± 2.3 a | 4.1 ± 0.1 |

| UV-B | 65.3 ± 3.4 b | 4.5 ± 0.3 | |

| Calena | CTR | 67.3 ± 3.2 b | 4.4 ± 0.3 |

| UV-B | 69.3 ± 2.0 b | 4.8 ± 0.3 | |

| Pearl | CTR | 95.0 ± 2.0 a | 3.4 ± 0.1 |

| UV-B | 86.7 ± 4.1 a | 4.1 ± 0.2 | |

| Mean effect | |||

| Alan | 76.7 ± 5.4 b | 4.3 ± 0.2 b | |

| Calena | 68.3 ± 2.4 b | 4.6 ± 0.2 a | |

| Pearl | 90.8 ± 2.8 a | 3.8 ± 0.2 c | |

| CTR | 83.4 ± 4.3 a | 3.9 ± 0.2 b | |

| UV-B | 73.8 ± 3.8 b | 4.4 ± 0.2 a | |

| ANOVA | |||

| Cultivar (A) | *** | *** | |

| Treatment (B) | ** | *** | |

| A × B | ** | n.s. | |

| Cultivar | Treatment | FW (g) | FW/DW (%) | Productivity (Kg/m2) | Length (cm) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypocotyl | Root | Total | |||||

| Alan | CTR | 0.012 ± 0.001 b | 92.06 ± 0.06 | 0.0045 ± 0.0001 a | 1.11 ± 0.03 | 2.79 ± 0.23 ab | 3.89 ± 0.23 a |

| UV-B | 0.009 ± 0.002 d | 87.60 ± 0.88 | 0.0031 ± 0.0001 bc | 0.65 ± 0.02 | 2.04 ± 0.27 bc | 2.69 ± 0.10 bc | |

| Calena | CTR | 0.013 ± 0.001 a | 88.95 ± 0.96 | 0.0034 ± 0.0003 b | 1.18 ± 0.03 | 3.47 ± 0.26 a | 4.65 ± 0.26 a |

| UV-B | 0.010 ± 0.001 c | 82.62 ± 0.71 | 0.0022 ± 0.0001 c | 0.65 ± 0.03 | 1.27 ± 0.09 c | 1.92 ± 0.10 c | |

| Pearl | CTR | 0.007 ± 0.001 e | 91.43 ± 0.56 | 0.0036 ± 0.0002 ab | 1.19 ± 0.03 | 1.84 ± 0.15 c | 3.03 ± 0.16 b |

| UV-B | 0.011± 0.001 bc | 88.56 ± 0.26 | 0.0035 ± 0.0001 b | 0.68 ± 0.02 | 1.86 ± 0.09 c | 2.54 ± 0.09 bc | |

| Mean effect | |||||||

| Alan | 0.010 ± 0.001 b | 89.83 ± 1.07 a | 0.0038 ± 0.0003 a | 0.88 ± 0.10 | 2.42 ± 0.21 a | 3.29 ± 0.29 a | |

| Calena | 0.012 ± 0.001 a | 85.79 ± 1.51 b | 0.0028 ± 0.0003 b | 0.91 ± 0.11 | 2.38 ± 0.50 a | 3.29 ± 0.61 a | |

| Pearl | 0.009 ± 0.001 c | 89.99 ± 0.70 a | 0.0036 ± 0.0001 a | 0.93 ± 0.12 | 1.85 ± 0.10 b | 2.78 ± 0.15 b | |

| CTR | 0.011 ± 0.001 a | 90.81 ± 0.99 a | 0.0039 ± 0.0003 a | 1.16 ± 0.03 a | 2.70 ± 0.26 a | 3.86 ± 0.25 a | |

| UV-B | 0.010 ± 0.010 b | 86.26 ± 1.70 b | 0.0029 ± 0.0003 b | 0.66 ± 0.01 b | 1.72 ± 0.14 b | 2.38 ± 0.14 b | |

| ANOVA | |||||||

| Cultivar (A) | *** | *** | *** | n.s. | ** | * | |

| Treatment (B) | ** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | |

| A × B | *** | n.s. | ** | n.s. | *** | *** | |

| Cultivar | Treatment | FW (g) | FW/DW (%) | Productivity (Kg/m2) | Hypocotyl Length (cm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alan | CTR | 0.025 ± 0.001 ab | 6.51 ± 0.87 | 1.49 ± 0.062 | 1.23 ± 0.07 |

| UV-B | 0.019 ± 0.002 bc | 9.07 ± 0.52 | 1.18 ± 0.016 | 0.60 ± 0.09 | |

| Calena | CTR | 0.030 ± 0.002 a | 8.79 ± 0.74 | 1.19 ± 0.066 | 0.91 ± 0.12 |

| UV-B | 0.017 ± 0.002 c | 10.76 ± 1.75 | 0.72 ± 0.037 | 0.53 ± 0.03 | |

| Pearl | CTR | 0.020 ± 0.001 bc | 7.09 ± 0.86 | 1.43 ± 0.056 | 1.14 ± 0.07 |

| UV-B | 0.024 ± 0.001 abc | 8.22 ± 0.27 | 1.09 ± 0.025 | 0.60 ± 0.02 | |

| Mean effect | |||||

| Alan | 0.022 ± 0.002 | 7.79 ± 0.73 | 1.34 ± 0.075 a | 0.92 ± 0.14 a | |

| Calena | 0.024 ± 0.003 | 9.77 ± 0.96 | 0.96 ± 0.111 b | 0.72 ± 0.10 b | |

| Pearl | 0.022 ± 0.001 | 7.65 ± 0.48 | 1.26 ± 0.082 a | 0.87 ± 0.12 ab | |

| CTR | 0.025 ± 0.003 a | 7.46 ± 0.93 b | 1.37 ± 0.095 a | 1.10 ± 0.06 a | |

| UV-B | 0.020 ± 0.002 b | 9.35 ± 1.13 a | 1.00 ± 0.124 b | 0.58 ± 0.02 b | |

| ANOVA | |||||

| Cultivar (A) | n.s. | n.s. | *** | * | |

| Treatment (B) | ** | * | *** | *** | |

| A × B | *** | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | |

| Stage | Cultivar | Treatment | Total Phenolics (mg GAE g−1 DW) | Flavonoids (mg CAE g−1 DW) | Antioxidant Capacity | TBARS (nmol g−1 DW) | Proline (µmol g−1 DW) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABTS (µmol TEAC g−1 DW) | DPPH (mg TEAC g−1 DW) | FRAP (µmol Fe (II) g−1 DW) | |||||||

| Sprouts | Alan | 22.21 ± 3.75 | 12.11 ± 2.31 | 90.53 ± 13.55 B | 10.35 ± 1.40 B | 116.12 ± 16.54 B | 16.01 ± 1.44 | 12.79 ± 4.15 B | |

| Calena | 21.45 ± 2.67 | 12.50 ± 1.62 | 182.69 ± 25.31 A | 10.85 ± 1.27 A | 135.89 ± 17.45 A | 18.13 ± 1.53 | 76.28 ± 17.82 A | ||

| Pearl | 21.23 ± 4.13 | 12.03 ± 2.93 | 97.98 ± 18.06 B | 9.35 ± 1.91 C | 120.37 ± 23.58 B | 17.60 ± 0.76 | 15.98 ± 3.22 B | ||

| CTR | 13.82 ± 1.61 B | 7.13 ± 1.68 B | 81.78 ± 34.86 B | 6.77 ± 1.35 B | 81.29 ± 13.25 B | 14.88 ± 1.84 B | 21.93 ± 9.58 B | ||

| UV-B | 29.44 ± 1.94 A | 17.29 ± 1.16 A | 165.69 ± 55.42 A | 13.59 ± 0.18 A | 166.96 ± 10.57 A | 19.61 ± 2.14 A | 48.10 ± 14.92 A | ||

| Microgreens | Alan | 34.32 ± 4.75 a | 16.56 ± 2.34 ab | 162.96 ± 24.37 ab | 29.24 ± 3.60 ab | 222.84 ± 29.37 a | 16.30 ± 0.88 b | 33.10 ± 4.17 | |

| Calena | 31.25 ± 4.48 a | 17.94 ± 3.19 a | 169.92 ± 24.05 a | 33.75 ± 3.54 a | 237.21 ± 41.45 a | 17.54 ± 4.03 b | 43.73 ± 7.05 | ||

| Pearl | 25.40 ± 3.17 b | 13.74 ± 2.26 b | 147.42 ± 16.67 b | 26.99 ± 3.44 b | 161.54 ± 22.63 b | 29.14 ± 4.21 a | 31.21 ± 1.89 | ||

| CTR | 21.48 ± 3.12 b | 10.54 ± 2.12 b | 113.09 ± 12.90 b | 22.69 ± 4.26 b | 140.23 ± 26.10 b | 25.27 ± 10.66 a | 34.65 ± 4.70 | ||

| UV-B | 39.17 ± 6.51 a | 21.62 ± 3.29 a | 207.11 ± 22.33 a | 37.29 ± 4.42 a | 274.17 ± 56.99 a | 16.71 ± 7.12 b | 37.37 ± 3.80 | ||

| Cultivar | Treatment | Neoxanthin | Violaxanthin | Lutein | Chlorophyll b | Chlorophyll a | β-carotene |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alan | CTR | 1.02 ± 0.14 | 0.67 ± 0.58 | 7.47 ± 0.35 bc | 8.92 ± 1.17 | 13.60 ± 2.90 | 2.11 ± 0.11 b |

| UV-B | 1.12 ± 0.15 | 1.29 ± 0.07 | 9.68 ± 0.38 ab | 12.88 ± 0.48 | 25.46 ± 0.92 | 2.97 ± 0.15 a | |

| Calena | CTR | 1.16 ± 0.21 | 1.35 ± 0.49 | 9.23 ± 0.51 ab | 8.92 ± 1.03 | 21.72 ± 3.39 | 3.06 ± 0.06 a |

| UV-B | 1.36 ± 0.08 | 1.26 ± 0.13 | 9.92 ± 0.42 a | 12.88 ± 0.75 | 25.95 ± 1.76 | 3.22 ± 0.14 a | |

| Pearl | CTR | 0.76 ± 0.04 | 0.86 ± 0.08 | 5.90 ± 0.28 c | 8.33 ± 0.17 | 13.54 ± 0.32 | 1.17 ± 0.04 c |

| UV-B | 1.36 ± 0.18 | 1.57 ± 0.24 | 9.33 ± 0.72 ab | 12.41 ± 1.00 | 24.24 ± 2.41 | 2.81 ± 0.26 a | |

| Mean effect | |||||||

| Alan | 1.07 ± 0.09 | 0.98 ± 0.18 | 8.58 ± 0.55 ab | 10.90 ± 1.05 ab | 19.53 ± 2.98 | 2.54 ± 0.21 b | |

| Calena | 1.26 ± 0.11 | 1.30 ± 0.23 | 9.57 ± 0.34 a | 12.80 ± 0.62 a | 23.83 ± 1.95 | 3.14 ± 0.07 a | |

| Pearl | 1.06 ± 0.16 | 1.21 ± 0.20 | 7.61 ± 0.84 b | 10.37 ± 1.02 b | 18.89 ± 2.63 | 1.99 ± 0.38 c | |

| CTR | 0.98 ± 0.09 b | 0.96 ± 0.19 | 7.53 ± 0.52 b | 8.86 ± 0.76 b | 16.29 ± 1.87 b | 2.11 ± 1.17 b | |

| UV-B | 1.28 ± 0.08 a | 1.37 ± 0.10 | 9.64 ± 0.28 a | 12.87 ± 0.41 a | 25.21 ± 0.94 a | 3.00 ± 0.11 a | |

| ANOVA | |||||||

| Cultivar (A) | n.s. | n.s. | ** | * | n.s. | *** | |

| Treatment (B) | * | n.s. | *** | *** | *** | *** | |

| A × B | n.s. | n.s. | * | n.s. | n.s. | *** | |

| Cultivar | Treatment | Neoxanthin | Violaxanthin | Lutein | Chlorophyll b | Chlorophyll a | β-carotene |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alan | CTR | 2.17 ± 0.19 | 3.51 ± 0.14 d | 29.52 ± 1.78 | 39.28 ± 1.89 | 95.99 ± 4.62 | 5.19 ± 0.10 |

| U-VB | 2.04 ± 0.06 | 6.56 ± 0.06 b | 25.14 ± 0.63 | 37.72 ± 1.61 | 100.57 ± 4.27 | 6.07 ± 0.34 | |

| Calena | CTR | 2.30 ± 0.14 | 5.25 ± 0.11 c | 27.89 ± 1.98 | 39.51 ± 1.48 | 95.83 ± 3.77 | 5.67 ± 0.36 |

| UV-B | 1.61 ± 0.18 | 7.89 ± 0.26 a | 23.15 ± 0.95 | 31.86 ±1.35 | 83.29 ± 3.13 | 5.47 ± 0.16 | |

| Pearl | CTR | 2.44 ± 0.29 | 1.30 ± 0.30 e | 25.43 ± 1.35 | 37.80 ± 2.67 | 88.24 ± 8.07 | 4.73 ± 0.42 |

| UV-B | 1.82 ± 0.13 | 6.12 ± 0.10 bc | 20.76 ± 0.60 | 32.24 ± 1.27 | 83.48 ± 3.04 | 5.34 ± 0.12 | |

| Mean effect | |||||||

| Alan | 2.10 ± 0.09 | 5.03 ± 0.69 b | 27.33 ± 1.29 a | 38.50 ± 1.66 | 98.28 ± 2.99 | 5.63 ± 0.25 | |

| Calena | 1. 95 ± 0.19 | 6.57 ± 0.60 a | 25.52 ± 1.45 ab | 35.69 ± 1.93 | 89.56 ± 3.56 | 5.57 ± 0.18 | |

| Pearl | 2.13 ± 0.20 | 3.71 ± 1.09 c | 23.09 ± 1.24 b | 35.02 ± 1.82 | 85.86 ± 4.00 | 5.03 ± 0.24 | |

| CTR | 2.30 ± 0.20 a | 3.35 ± 1.00 b | 27.61 ± 1.82 a | 38.87 ± 1.85 a | 93.35 ± 5.48 | 5.20 ± 0.37 | |

| UV-B | 1.82 ± 0.16 b | 6.86 ± 0.48 a | 23.01 ± 1.27 b | 33.94 ± 2.05 b | 89.11 ± 5.82 | 5.62 ± 0.28 | |

| ANOVA | |||||||

| Cultivar (A) | n.s. | *** | * | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | |

| Treatment (B) | * | *** | ** | ** | n.s. | n.s. | |

| A × B | n.s. | *** | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | |

| Morphological and Biochemical Parameters | Pearson’s Coefficient (r) | |

|---|---|---|

| Sprouts | Microgreens | |

| Hypocotyl length | −0.94722 * | −0.86079 * |

| FW | 0.246662 | −0.31593 |

| Proline | 0.273627 | 0.295374 |

| Violaxanthin | 0.500319 | −0.47329 |

| Neoxanthin | 0.568232 | −0.64709 |

| ABTS | 0.645521 | 0.89464 * |

| DW/FW % | 0.657059 | 0.6323 |

| TBARS | 0.676616 | −0.65688 |

| b-carotene | 0.722391 | 0.519325 |

| Chlorophyll b | 0.725287 | −0.49009 |

| Lutein | 0.767235 | −0.41462 |

| Chlorophyll a | 0.772426 | −0.10377 |

| FRAP | 0.960047 * | 0.928229 * |

| DPPH | 0.984618 * | 0.915949 * |

| Total phenolics | 0.987404 * | 0.877433 * |

| Flavonoids | 0.989792 * | 0.921436 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Santin, M.; Clemente, C.; Vinci, G.; Galasso, I.; Brambilla, I.M.; Angelini, L.G.; Ranieri, A.; Castagna, A.; Tavarini, S. Cultivar-Specific Responses of Camelina (Camelina sativa (L.) Crantz) Sprouts and Microgreens to UV-B Radiation: Effects on Germination, Growth, Biochemical Traits, and Stress-Related Parameters. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 1464. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121464

Santin M, Clemente C, Vinci G, Galasso I, Brambilla IM, Angelini LG, Ranieri A, Castagna A, Tavarini S. Cultivar-Specific Responses of Camelina (Camelina sativa (L.) Crantz) Sprouts and Microgreens to UV-B Radiation: Effects on Germination, Growth, Biochemical Traits, and Stress-Related Parameters. Horticulturae. 2025; 11(12):1464. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121464

Chicago/Turabian StyleSantin, Marco, Clarissa Clemente, Giampiero Vinci, Incoronata Galasso, Ida Melania Brambilla, Luciana Gabriella Angelini, Annamaria Ranieri, Antonella Castagna, and Silvia Tavarini. 2025. "Cultivar-Specific Responses of Camelina (Camelina sativa (L.) Crantz) Sprouts and Microgreens to UV-B Radiation: Effects on Germination, Growth, Biochemical Traits, and Stress-Related Parameters" Horticulturae 11, no. 12: 1464. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121464

APA StyleSantin, M., Clemente, C., Vinci, G., Galasso, I., Brambilla, I. M., Angelini, L. G., Ranieri, A., Castagna, A., & Tavarini, S. (2025). Cultivar-Specific Responses of Camelina (Camelina sativa (L.) Crantz) Sprouts and Microgreens to UV-B Radiation: Effects on Germination, Growth, Biochemical Traits, and Stress-Related Parameters. Horticulturae, 11(12), 1464. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121464