1. Introduction

Known as the “sacred fruit of the western regions”, Korla fragrant pears are favored by consumers for their dense texture, heat-clearing properties, and abundant juice [

1,

2]. However, their thin skin and delicate flesh make them highly susceptible to mechanical damage. Before reaching consumers, the pears undergo a series of post-harvest processes, including picking, storage, grading, and transportation, during which the primary damaging loads are compression, impact, and the synergistic effect of both. Damaged pears experience rapid quality deterioration, accelerated decay, and microbial infestation, thereby reducing their commercial value. Consequently, industry practitioners often discard damaged pears directly, resulting in significant waste [

3]. While this strategy reduces management costs, it overlooks the potential value assigned by industry standards to damaged pears for deep processing within specific periods—such as producing pear paste or pear wine—and the direct disposal of damaged pears causes substantial economic losses [

4,

5]. Furthermore, as a specialty fruit of Xinjiang, practitioners frequently adopt a business model of off-season disposal after storage. However, they currently face challenges in accurately predicting whether the quality of damaged fragrant pears post-storage can still hold economic value [

6]. Strict control of storage quality and timely disposal before quality declines below relevant industry standards can effectively reduce economic losses and enhance market competitiveness. Therefore, precisely quantifying the internal quality indicators of Korla fragrant pears during storage can determine their optimal consumption window, maximize commercial value, and ensure value conversion before quality degrades below critical thresholds. This approach could enhance pear utilization, increase industrial economic benefits, and promote the sustainable development of the fragrant pear industry.

Among the internal quality indicators of Korla fragrant pears, hardness and SSC are particularly critical and are commonly used to assess the quality of pears and other fruits [

7,

8]. Newly harvested Korla fragrant pears are rich in protopectin and starch, exhibiting a firm texture. During storage, enzymatic activity within the pears gradually promotes softening [

9]. Soluble solids content (SSC), expressed as a percentage, refers to water-soluble compounds in the juice, including sugars, acids, vitamins, and minerals. Its concentration determines the nutritional value and taste of fragrant pears—higher SSC correlates with sweeter flavor—making it a key quality indicator [

10]. Consequently, hardness and SSC jointly serve as decisive parameters for pear taste and flavor, forming the core criteria for determining the optimal consumption period. Simultaneously, mechanical damage sustained during harvesting and post-harvest processing significantly impacts these parameters. Clarifying the internal quality changes in fragrant pears under different damage types is, therefore, essential for evaluating storage quality. Current research includes studies on quality evolution in damaged fruits during storage: Zhu et al. [

11] identified changes in hardness and SSC of impact-damaged Crown pears during ambient storage; Durigan et al. [

12] determined quality alterations (SSC, acidity) in Tahitian citrus subjected to impact, compression, and cutting before storage at 25 ± 1 °C and 65 ± 5% RH; Sanches et al. [

13] explored SSC and titratable acid changes in avocados with impact, compression, and cutting injuries during storage; Kasat et al. [

14] measured SSC, titratable acidity, sugar–acid ratio, and hardness in peaches with impact, compression, and cutting damage stored at 10 ± 1.5 °C and 85 ± 2% RH for 8 days, finding quality deterioration starting on day 6 with impact causing the most severe damage; Pathare and Mai [

15] observed damaged area, SSC, and pigment content in tomatoes stored at 10 °C and 22 °C for 10 days post-injury, noting significant influences from storage temperature and impact height. These studies collectively demonstrate the substantial effects of mechanical damage types on fruit storage quality. However, the evolution of internal quality in Korla fragrant pears under different damage forms remains rarely studied. Thus, clarifying the influence patterns of hardness and SSC changes in Korla fragrant pears with varying damage types during storage and achieving accurate prediction of storage quality indicators still requires in-depth research.

To accurately predict changes in quality indicators of damaged fragrant pears during storage, establishing a rapid and precise prediction method is essential. In recent years, neural networks have proven to be highly effective in solving complex prediction and modeling problems across various fields. Among them, the adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system (ANFIS), characterized by fast convergence, strong self-learning capability, and high adaptability, is widely applied in fruit and vegetable quality prediction [

1,

16,

17]. Specifically, Niu et al. [

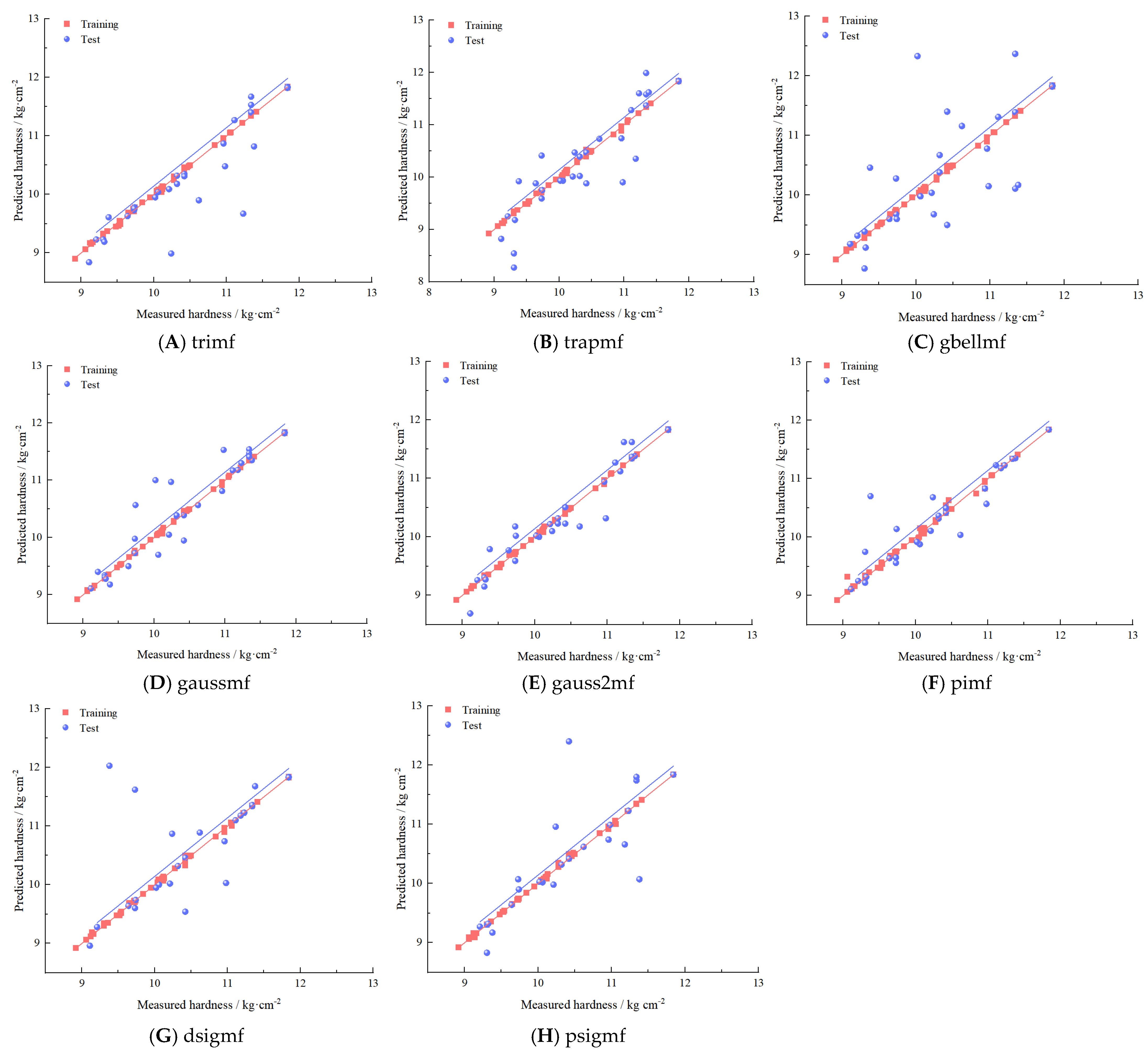

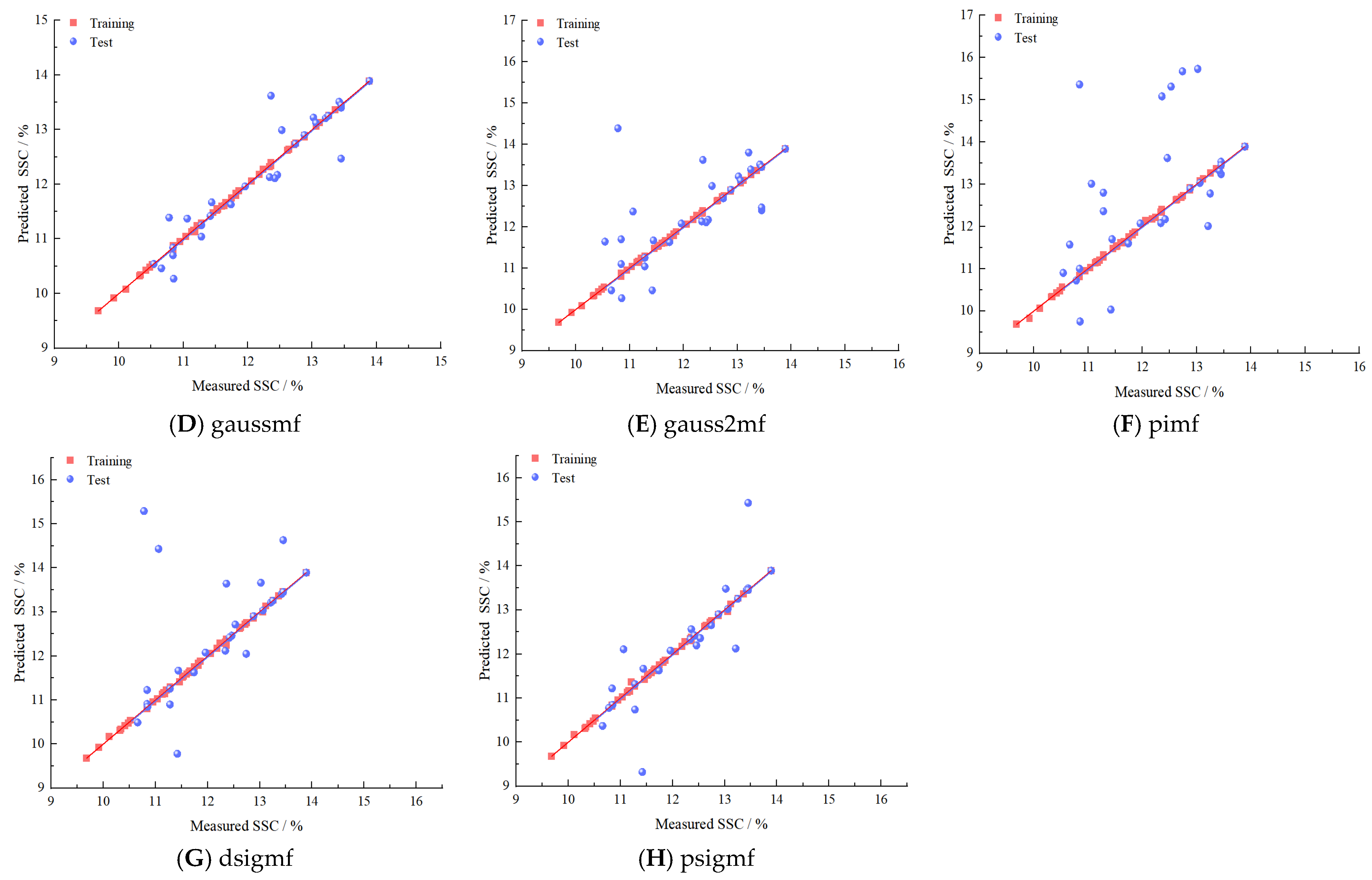

18] employed an ANFIS model for predicting the hardness of Korla fragrant pears, in which the gbellmf membership function achieved accurate prediction of pear hardness, demonstrating its feasibility for forecasting hardness in Korla fragrant pears. Liu et al. [

19] used ANFIS to predict storage quality changes in Korla fragrant pears, revealing differential evolution patterns in SSC and vitamin content during storage, with the gbellmf and trimf membership functions achieving optimal prediction accuracy for SSC and vitamin content, respectively. Jiang et al. [

20] measured ascorbic acid retention in fresh-cut pineapples during storage and developed an ANFIS prediction model, identifying the trimf membership function as optimal for ascorbic acid prediction. These studies collectively validate ANFIS effectiveness for predicting fruit quality during storage, providing valuable references for internal quality prediction of stored fragrant pears. However, research applying ANFIS to predict the internal quality of fragrant pears with different damage types during storage remains scarce. In summary, it is essential to reveal the impact of different mechanical damage types on the quality changes in Korla fragrant pears during storage and establish an ANFIS-based prediction method for the internal quality of pears under various damage forms during storage, thereby providing practical guidance for industrial storage management strategies.

This study revealed the changing patterns of hardness and SSC in Korla fragrant pears under different damage types during storage, constructed eight quality prediction models based on the ANFIS with distinct membership functions, and identified the optimal prediction model. It provides a significant theoretical basis and methodological reference for optimizing storage management and enhancing the quality control precision of Korla fragrant pears. The remainder of this study is organized as follows.

Section 2 introduces the test materials, test methods, quality indicator measurement, and the construction and evaluation system of the adopted prediction models.

Section 3 reveals the variation patterns of hardness and SSC in Korla fragrant pears under different damage types during storage, constructs eight pear quality prediction models based on ANFIS with different membership functions, and selects the optimal prediction model. Additionally, traditional PLSR and SVR models are established for comparative analysis. Finally,

Section 4 discusses the research findings and compares them with existing literature, analyzing application scenarios and limitations. The main conclusions are summarized, and potential directions for future research are proposed, providing an important theoretical basis and methodological reference for optimizing the storage management and enhancing the quality control of Korla fragrant pears.

2. Materials and Methods

To ensure test reproducibility, this section systematically describes the materials, test equipment, damage-induction methods, quality indicator measurement procedures, and the construction and evaluation system of the prediction models used in the study.

2.1. Test Materials

The experimental pears were harvested from a conventionally managed Korla fragrant pear orchard at the 15th Company of the 10th Regiment in Alaer City, First Division of the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps, with trees aged 15 years. Harvesting occurred on 22 September 2022, during which gloves were worn to prevent human-induced damage. Harvested pears were wrapped in foam nets to avoid mechanical damage during transport. After being transported to the laboratory, pears were selected based on uniform size. A total of 610 pears weighing 130 ± 5 g, free from deformities, damage, or pest/disease infestation, were selected.

2.2. Impact Test

The fruit drop damage test bench, as shown in

Figure 1, comprises a lifting device and an adsorption unit, where the adsorption unit includes an engine body, vacuum generator, suction valve, and air compressor, while the lifting device consists of a linear guide rail, pneumatic motor, drive screw, and extension arm. Operational procedures were as follows: first, the suction valve was raised to a specified height via the lifting device; then, the sample was adsorbed onto the suction valve through the adsorption unit; finally, suction was disengaged to allow free-fall impact onto contact materials on the platform surface, creating impact damage on the test bench, with pears being quickly caught post-impact to prevent secondary damage.

Preliminary impact tests revealed that when fragrant pears impacted steel plates, a drop height of 275 mm caused damage volume of 900 mm3 with no visible epidermal damage but minor flesh damage; at 400 mm height, damage volume reached 2400 mm3 showing superficial epidermal marks and moderate flesh destruction; at 670 mm height, damage volume measured 5700 mm3 with significant epidermal deformation, extensive flesh damage, and disrupted tissue structure—though without epidermal rupture or juice exudation. Consequently, impact heights for this experimental batch were determined as 275 mm, 400 mm, and 670 mm based on damage severity, totaling 180 pears.

2.3. Compression Test

A universal compression testing machine (WD-D3-7, Shanghai Zhuojie Instrument Equipment Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) was employed for compression tests at a rate of 5 mm/s. Compression ceased immediately upon visual observation of pear epidermal rupture by the steel flat-plate indenter, followed by prompt retraction of the indenter. Preliminary tests indicated damage volumes of 900 mm3 at 3.52 mm compression, 2400 mm3 at 4.66 mm compression, and 5700 mm3 at 7.16 mm compression. Epidermal rupture occurred when compression exceeded 11 mm, indicating yield limit attainment. Consequently, compression levels for formal tests were set at 3.52 mm, 4.66 mm, and 7.16 mm. A total of 180 pears were subjected to compression tests.

2.4. Impact-Compression Synergy Test

Synergistic load testing was based on single-impact and compression tests; three impact gradients and three compression gradients were used, and a total of 180 pears were employed. According to three damage volumes, 900 mm3, 2400 mm3, and 5700 mm3, the impact-compression synergy tests corresponded to three parameter tiers: 235 mm impact with 3.0 mm compression, 330 mm impact with 3.7 mm compression, and 570 mm impact with 4.4 mm compression. Impact and compression loads were maintained at the identical contact point throughout.

2.5. Internal Quality Indicator Measurement

Hardness was measured using a fruit hardness tester, diameter of the measuring head is 3.5 mm(Aidebao GY-1, Yueqing Aidebao Instrument Co., Ltd., Leqing, China). Four equidistant points along the pear’s equatorial zone were selected (excluding the damaged area). The tester probe was vertically inserted slowly into measurement sites until reaching the 10 mm depth mark, then immediately retracted. The displayed value represented the hardness at that location. After each measurement, the crank arm was slowly rotated back to its original position, the instrument was zeroed by pressing the reset button, and subsequent measurements commenced after dial reset. Experimental data were recorded, with the mean value of four measurements saved in kg·cm−2.

SSC was determined using a handheld refractometer (LB32T, Guangzhou Suwei Electronics Technology Co., Ltd., Guangzhou, China). Four equidistant equatorial points were selected. Peeled flesh segments were excised with a blade, squeezed to extract juice, and droplets were placed on the calibrated refractometer. Values at the bright/dark boundary junction were recorded, with results averaged.

2.6. Damage Volume Calculation

Given the three-dimensional nature of pear damage morphology, damage volume was adopted as the evaluation metric to accurately quantify impact damage [

21]. Tested pears were numbered and left at ambient temperature for 24 h post-impact. After peel removal, browning became visible in damaged areas while undamaged regions retained original coloration. The browned volume was, thus, measured as damage volume. As shown in

Figure 2, using a digital vernier caliper, the browning depth d, major axis a, and minor axis b of the damaged area were recorded. Damage volume was calculated according to Mahdi et al. [

22] using Equation (1).

where d is the depth of the fruit damaged area, mm; a is the major axis of the fruit damaged area, mm; b is the minor axis of the damaged area, mm.

2.7. Storage Trial

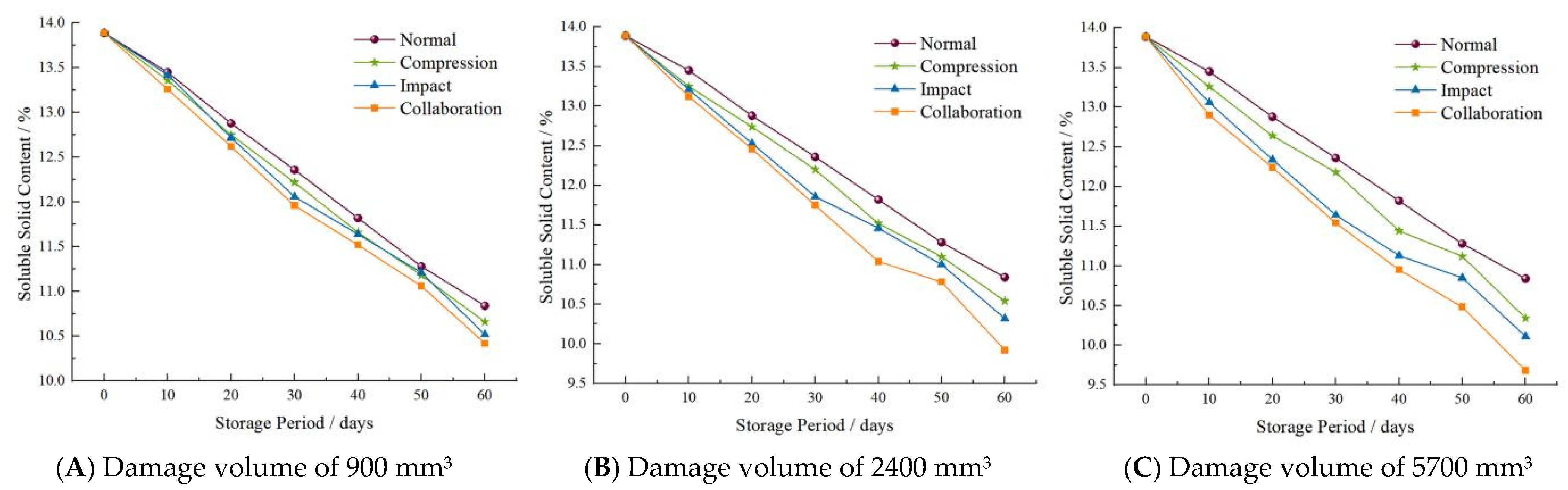

The storage experiment simulated actual shelf-life conditions, with an average temperature of 15 °C and an average humidity of 56%. Korla fragrant pears were categorized into 10 groups based on different damage types and damage volumes. Among these, impact damage, compression damage, and impact-compression synergy damage each corresponded to three damage volumes (900, 2400, 5700 mm3) comprising 9 groups of 540 pears, and there was a group of 70 undamaged pears, totaling 610 pears. Every 10 days, 10 pears were randomly selected from each group to measure their hardness and SSC, and the average value of the test results is calculated.

2.8. ANFIS Model

This study employed the ANFIS modeling to establish prediction models correlating storage duration, damage volume, and damage types with internal quality indicators of fragrant pears. ANFIS constructs fuzzy if-then rules with appropriate membership functions to generate specified input-output relationships [

23]. Combining self-learning capability with fuzzy systems, it utilizes neural network architectures to represent fuzzy processing, fuzzy inference, and precise computation, thereby forming a self-organizing hybrid neural network. Pear sample data were randomly divided into 7:3 training-test sets. Eight membership functions were input: triangular membership function (trimf), trapezoidal product of two sigmoids membership function (trapmf), generalized bell-shaped membership function (gbellmf), Gaussian membership function (gaussmf), double Gaussian membership function (gauss2mf), Pi curve membership function (pimf), difference between two sigmoids membership function (dsigmf), and product of two sigmoids membership function (psigmf). Hybrid learning-refined ANFIS parameters per epoch while reducing computational errors, the fault tolerance was set to 0 to ensure prediction accuracy, with the number of iterations set to 100, as increasing the number of iterations beyond this point does not significantly improve model accuracy [

1]. A three-input-one-output architecture was implemented: inputs being damage volume (0, 900, 2400, 5700 mm

3), storage days (0, 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60), and damage types (normal = 1, compression = 2, impact = 3, impact-compression synergy = 4), and output being pear storage quality indicators. Different membership functions directly determined model outputs, with the system architecture shown in

Figure 3.

2.9. Model Evaluation Methodology

The coefficient of determination (R

2) and root mean square error (RMSE) were employed to evaluate model performance. A high-precision prediction model typically exhibits higher R

2 values and lower RMSE. The calculation formulas are as follows:

where n is the total number of samples; ŷ

i represents the predicted value of the

i-th sample; y

i denotes the actual value of the

i-th sample; ȳ signifies the mean of actual values.

4. Discussion

This study clarified the variation laws of internal quality in Korla fragrant pears under different damage types during storage and established a high-precision prediction model using ANFIS. Zhu et al. [

11] investigated the quality changes, hardness, and SSC of impact-damaged Crown pears during ambient storage. Their results indicated that the decline rates of hardness and SSC gradually increased with higher drop heights and prolonged storage time. This aligns essentially with the internal quality variation laws observed for impact-damaged fragrant pears in the present study, further corroborating the physiological process whereby mechanical damage universally accelerates fruit senescence and deterioration. This deterioration may be associated with damage-induced ethylene burst, respiratory climacteric, increased cell membrane permeability, and the degradation of cell wall structures coupled with nutrient consumption resulting from enhanced activity of related enzymes. However, research primarily focused on single-impact damage but did not consider or compare the differential impact patterns of other damage types prevalent in actual postharvest handling, which exhibit distinct mechanisms affecting pear storage quality. This study, conversely, revealed the decay rates and variation laws of internal quality indicators in fragrant pears under different damage types, providing a more comprehensive basis for accurately assessing postharvest damage risks in pears.

Regarding prediction models, Liu et al. [

30] employed ANFIS to predict the internal quality of damaged fragrant pears during storage, finding that the ANFIS model with the trimf membership function achieved optimal prediction accuracy for both pear hardness and SSC. Zhang et al. [

1] also successfully used an ANFIS model to predict peel color changes in damaged pears during storage. These studies demonstrate the predictive capability of ANFIS models for fragrant pear quality. Nevertheless, they did not delve into the influence of different damage types on pear quality prediction. The results of this study can be directly applied to optimize the postharvest management strategies of Korla fragrant pears. The established correlation between damage levels, damage types, and storage duration provides clear operational guidance, as the storage life of fragrant pears varies significantly under different damage forms and severity levels. According to the Chinese National Quality Standard for Korla Fragrant Pears [

5], and by integrating both SSC and hardness indicators, the optimal processing window for damaged pears can be determined as follows: when the damage volume is 900 mm

3, pears under all three damage types must be processed within 40 days of storage. When the damage volume increases to 2400 mm

3, pears subjected to synergistic loads require processing within 30 days, while those under impact and compression loads can be extended to 40 days. With a further increase in damage volume to 5700 mm

3, pears under all damage forms need to be processed within 30 days of storage to mitigate economic losses caused by rapid quality deterioration. These specific thresholds enable the implementation of graded storage and prioritized processing protocols. Meanwhile, regarding packaging design guidance, this study provides quantitative support for developing targeted cushioning solutions. Among them, impact and impact-compression synergistic loads lead to accelerated quality deterioration in fragrant pears. Therefore, packaging should be specifically engineered to mitigate these high-risk damage types through enhanced cushioning materials and effective structural design. Furthermore, the ANFIS prediction model facilitates differentiated storage and precision processing tailored to the diverse quality standards of various processing enterprises. By determining the patterns of quality changes in pears, one can determine the optimal processing window for each batch. This enables decision-makers to dynamically allocate pears to the most suitable sales channels, such as those for high SSC juice or hardness-sensitive pear paste, based on real-time conditions, thereby maximizing the economic value of the Korla fragrant pear industry. For future industry implementation of this prediction model, we propose a three-phase approach: developing mobile applications based on the ANFIS model for real-time quality monitoring; validating the model with larger datasets across different growing regions and storage conditions through industry–academia collaboration; and integrating the prediction system with existing quality standards while conducting economic feasibility analyses to demonstrate cost–benefit advantages to stakeholders.

The findings of this study elucidated the variation patterns of storage quality in pears under different damage types and successfully predicted the internal quality parameters of Korla fragrant pears during storage using the ANFIS modeling approach. Simultaneously, this study has certain limitations. The damage types simulated experimentally may not fully encompass all complex composite damage scenarios encountered in real logistics. Storage conditions, such as temperature and humidity, were fixed at levels typical for shelf-life studies; actual production also involves various storage methods, like cold storage and cellar storage. Therefore, future research should consider incorporating a wider range of damage scenarios and different storage conditions, while also exploring the adaptability and transferability of the prediction models across varying environmental conditions. This study provides a theoretical foundation for formulating differentiated storage and sales strategies based on damage assessment in fragrant pears, ultimately aiming to reduce postharvest losses and enhance the economic benefits of the fragrant pear industry.