Abstract

Nipa sap is an excellent microbial nutrient and carbon source since it contains essential minerals and vitamins, in addition to sugars. In this study, nipa sap was successfully fermented to acetic acid by the industrially important Moorella thermoacetica without additional trace metals, without inorganics, or without yeast extract. Although microbial growth kinetics differed from one nutrient condition to another, acetic acid concentrations obtained without trace metals, without inorganics, and without yeast extract supplements were in the same range as that with full nutrient, confirming that nipa sap is a good nutrient source for M. thermoacetica. Fermentations in vials and fermenters showed comparable acetic acid production trends but acetic acid concentrations were higher in fermenters. Upon economic analysis, it was found that the most profitable nutrient condition was without yeast extract. It reduced the cost of culture medium from $1.7 to only $0.3/L, given that yeast extract costs $281/kg, while nipa sap can be available from $0.08/kg. Minimal medium instead of the traditional complex nutrient simplifies the process. This work also opens opportunities for profitable anaerobic co-digestion and co-fermentation of nipa sap with other biomass resources where nipa sap will serve as an inexpensive nutrient source and substrate.

1. Introduction

An enormous increase in acetic acid demand, together with environmental and political concerns about fossil-derived products augmented the demands for bio-based acetic acid from renewables [1,2]. Cost-effective and efficient bio-based acetic acid production requires competitive microorganisms.

Acetogenesis by Moorella thermoacetica (formerly known as Clostridium thermoaceticum) presents important advantages compared to the traditional vinegar process. M. thermoacetica can convert CO2 as well as a wide range of biomass-derived compounds (glucose, fructose, xylose, rhamnose, arabinose, decomposed and dehydrated compounds, etc.) to acetic acid as the sole product in near stoichiometry with a high conversion efficiency of 86 to 98% [3,4,5], as opposed to only 27% for the vinegar process [6]. M. thermoacetica offers environmental and chemical advantages but it needs high levels of nutrients to sustain viability, cell growth, metabolism, and productivity [7,8,9], which adds significantly to the cost of fermentation, and can be one obstacle for process commercialization.

The economic feasibility and viability of producing bioderived organic acids from fermentation depend on using low-cost nutrients and carbon sources in the medium. Although some minimal mediums for M. thermoacetica have been reported, external inorganic nutrients were still added in these studies, and the proposed yeast extract substituents add cost to the fermentation [7,8,9]. For example, Witjitra et al. [9] proposed soy flour, corn steep, and ethanol stillage as yeast extract replacements but they are still expensive, accounting for $0.5/kg. They increase the process cost.

On the other hand, nipa sap is available for only $0.08/L [10]. It is a sugar-rich liquid collected from nipa (Nypa fruticans), a wild palm that grows along coastal areas, river estuaries, and mangrove forests with brackish water environments [11]. By tapping the stalk of the nipa palm, it is possible to extract sap on a daily basis with a mean sap yield of 1.3 L/palm/day [12]. We have demonstrated previously that nipa sap can be converted to acetic acid [3,4,5], but fermentation with fewer nutrients has never been explored.

In an effort to reduce fermentation costs, this study focuses on evaluating nipa sap as an economical nutrient and carbon source for M. thermoacetica. To gain a better understanding of the fermentation, growth kinetics, and acetic acid production by M. thermoacetica under various nutrient conditions, experiments were performed using nipa sap as substrate. The results demonstrated that nipa sap can be fermented effectively to acetic acid by M. thermoacetica without inorganic nutrient supplements. The inorganics naturally present in nipa sap played the role of nutrients for microbial growth and the corresponding fermentation to acetic acid. Most importantly, nipa sap was also demonstrated to be a yeast extract substitute and drastically reduced medium price.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Concentrated and frozen nipa sap was received from Sarawak, Malaysia. Invertase solution (EC No.3.2.1.26) with a minimal activity of 4 units/mL was purchased from Wako Pure Chemical Industries Ltd., Osaka, Japan. M. thermoacetica (formerly Clostridium thermoaceticum) ATCC 39073 was used for acetic acid fermentation in this study. Freeze-dried culture of the bacterium was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA).

2.2. Hydrolysis of Nipa Sap

To prepare nipa sap for fermentation, 200 g of the concentrated nipa sap was diluted with Milli-Q water to a total volume of 1.00 L to reach chemical concentrations similar to those of the original sap. The enzymatic hydrolysis of sucrose in nipa sap solution was conducted by 3.92% v/v invertase solution at room temperature for 30 min. To clarify the role of nutrients in nipa sap, a standard sugar solution including 100 g/L glucose and 100 g/L fructose was also prepared.

2.3. Batch Fermentation of Nipa Sap Hydrolysate

The procedures for the revival of M. thermoacetica and the subsequent inoculum preparation were carried out as reported by Nakamura et al. [13]. Acetic acid fermentations of hydrolyzed nipa sap and standard sugars under various nutritional supplements were conducted in 50-mL vials as well as in a 500-mL DPC-2A fermenters (Able Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) at 60 °C with a stirring rate of 300 rpm and under N2 atmosphere.

The vial fermentation method is detailed by Nakamura et al. [13]. Table 1 shows the classification and concentration of nutrients used for fermentation with M. thermoacetica. The full media composition and preparation are detailed by Rabemanolontsoa et al. [4]. The nutrient solution for batch fermentation by M. thermoacetica includes yeast extract (5 g/L), inorganic compounds (1 g/L (NH4)2SO4, 0.25 g/L MgSO4·7H2O, 0.04 g/L Fe(NH4)2(SO4)2·6H2O, 0.24 mg/L NiCl2·6H2O, 0.29 mg/L ZnSO4·7H2O, 0.017 mg/L Na2SeO3), reducing compound (0.1 g/L cysteine·HCl·H2O) and oxidation-reduction indicator (1 mg/L resazurin). Since resazurin is not a nutrient, has no effect on fermentation, and is used only to verify anaerobia, it is not listed in Table 1. For vial fermentations, additional compounds were added as buffer with the following concentrations: 0.415 g/L of NaOH, 5 g/L of NaHCO3, 4.4 g/L of K2HPO4, 7.5 g/L of KH2PO4. Given that high sugar concentration can inhibit M. thermoacetica, total sugar concentration in nipa sap hydrolysate was corrected to be 10 g/L in the broth.

Table 1.

Classification, concentration and price of nutrients used for fermentation with M. thermoacetica.

Fermentations in 500-mL fermenters are detailed elsewhere [4]. A working volume of 200 mL was created by pouring 14 mL of hydrolyzed nipa sap, 20 mL of M. thermoacetica inoculum, and 166 mL of nutrient solution into each fermentation system, making a total sugar concentration of 10 g/L. Concentrations of nutrients in fermenters were the same as for vial fermentations and are detailed in Table 1. While buffer compounds were added in vial fermentations, the pH was maintained at 6.5 ± 0.1 in fermenters by automatic titration with 2 N NaOHaq. solution which was prepared separately and attached to the fermenter. Anaerobic condition was regulated with a DO sensor.

To determine minimal nutrient requirements, yeast extract and/or inorganics were systematically explored as designed in Table 1. All fermentation systems, vials, substrate, nutrient, and buffer solutions were sterilized in an autoclave at 121 °C for 20 min. To correct acetic acid produced from the nutrients, inoculum and invertase, fermentations without substrates (blank samples) were performed under the same conditions. Samples were collected at specific time intervals by syringes through a sampling port and then stored at –31 °C for further analyses. Separate experiments working with the same fermentation protocol and substrate were repeated and provided variations in sugars, acetic acid concentration, and optical density with coefficients of variation of only 4.3%, 2.2%, and 4.9%, respectively.

2.4. Analyses

The concentrations of sucrose, glucose and fructose were determined by HPLC (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) equipped with a RI detector and a Shodex sugar KS-801 column (Showa Denko, Kanagawa, Japan). The column was maintained at 80 °C and eluted with Milli-Q water at a flow rate of 1 mL/min. The inorganic elements in the nipa sap were analyzed by ion chromatography (IC) and inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) at AU Techno Services Co., Ltd. (Osaka, Japan). The samples were analyzed in triplicate, and the results are expressed as the average values.

To quantify the concentrations of acetic acid, an Aminex HPX-87H column (Bio-rad, Hercules, CA, USA) was used at 45 °C with 5 mM aqueous H2SO4 solution as mobile phase, and the flow rate was set at 0.6 mL/min. Prior to injection into HPLC, samples were filtered through a 0.45 µm membrane to remove microorganisms.

The sensitivity of the methods was determined by calculating the limit of detection (LOD) based on the residual standard deviation of a regression line and its slope. The values of LOD for each instrument to the compounds were measured using the equation: LOD = (σ/S) × 3.3 [4], where σ is the standard deviation calculated as STEYX by a built-in formula in the excel program and S is the slope of the calibration curve. The LOD for HPLC method was between 2.7 and 4.5 mg/L.

The growth of M. thermoacetica was determined by measuring the optical density (OD) using Shimadzu UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Kyoto, Japan) at 660 nm with water as reference.

In order to evaluate the performance of the fermentation techniques, conversion efficiency and acetic acid production were calculated, respectively, according to Equations (1) and (2).

For economic analysis, nutrient prices were taken from Sigma Aldrich [14]. Supplementary nutrient per liter of media for each condition was calculated according to the following equation:

where n represents each supplementary nutrient.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Chemical Composition and Hydrolysis of Nipa Sap

The chemical composition of nipa sap before and after hydrolysis by invertase is presented in Table 2. The raw nipa sap before hydrolysis consisted of 82.7 ± 0.9 g/L of sucrose, 29.9 ± 0.1 g/L of glucose, 38.5 ± 0.2 g/L of fructose, 1.6 ± 0.1 g/L of lactic acid and 9.1 ± 3.5 g/L of inorganics. Sucrose is the main component, while hexoses and lactic acid can be products from spontaneous hydrolysis and fermentation of primary sucrose in original nipa sap during the collection and storage process [15,16].

Table 2.

Chemical composition of nipa sap before and after enzymatic hydrolysis.

Because M. thermoacetica cannot metabolize sucrose directly, enzymatic treatment with invertase was conducted. After invertase treatment, the concentrations of glucose and fructose increased to 71.4 ± 1.1 and 83.1 ± 2.6 g/L, respectively. Glucose increased by 41.5 ± 1.1 g/L, while fructose increased by 44.6 ± 2.6 g/L. The total increase in glucose and fructose was 86.1 g/L, and their anhydride forms account for 81.8 g/L altogether, which corresponds to the amount of sucrose that was hydrolyzed. This shows that invertase could cleave the α-1,4-glycosidic bonds of sucrose, resulting in the formation of a nearly equimolar mixture of glucose and fructose. Although it was suggested elsewhere that sucrose concentration above 50 g/L can inhibit invertase [17], in this study invertase could hydrolyze 99% of the 82.7 g/L initial sucrose. It seems that the minor compounds and minerals in nipa sap did not affect the hydrolysis in a negative way. Only around 0.9 g/L of sucrose remained in the hydrolysate. This might be due to the slight inhibitory effect of glucose acting as a non-competitive inhibitor for the enzyme and fructose being a competitive inhibitor [18].

In 9.1 ± 3.5 g/L of total inorganics, Na, K and Cl were identified as the major elements. In addition, minor concentrations of P, S, Mg, and Ca were (2.6 ± 3.5) × 10−2, (5.7 ± 0.3) × 10−2, (4.4 ± 0.9) × 10−2, (3.6 ± 3.8) × 10−3 g/L, respectively. Trace amounts of Mn and Al were also found in this sap.

Similar elements such as Na, K, Mg, Ca, P, S, Si, and Cl in nipa sap from Thailand were reported by Tamunaidu and Saka [19]. Moreover, Saengkrajang et al. [20] analyzed elements including K, Na, Ca, Mg, Cu, Fe, Mn, Zn, P, I, Cr and Si in nipa syrup from Thailand using inductively coupled plasma-optical emission spectrometry. The research showed the presence of main minerals such as K, Na, P, Mg, Si, and Ca in nipa syrup. Interestingly, trace amounts of Fe, Cu, I, Mn, Zn, and Cr were detected. Therefore, the presence of trace inorganics in nipa sap may depend on areas where nipa palm grows [21]. In addition to minerals, minor organic compounds like proteins, phenolics, flavonoids [21], and vitamin C [22] were reported. As reviewed by Nguyen et al. [23], various proteins and vitamins exist in many kinds of palm sap. Minerals, proteins, and vitamins may be used for acetic acid fermentation by M. thermoacetica. Importantly, S, Mg, Fe, and Zn contained in nipa sap are required nutrients for microbial cultivation [4]. Phenolic and flavonoid compounds known as powerful antioxidants could have beneficial bioactivities towards M. thermoacetica [21].

3.2. Batch Fermentation of Nipa Sap Hydrolysate

3.2.1. Fermentation of Hydrolyzed Nipa Sap with and without Nutrient Supplements in Comparison with Standard Sugars

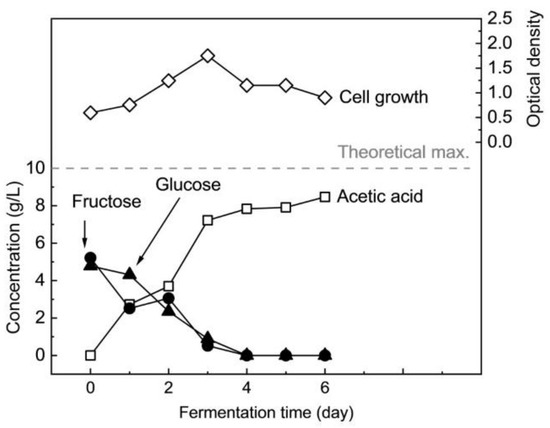

Figure 1 shows a typical profile of pH-controlled fermentation of nipa sap hydrolysate with full nutrient in the fermenter. Optical density increased exponentially in the first three days and then decreased noticeably. Glucose and fructose concentrations were rapidly reduced in the first three days and were completely consumed after around 4 days. As a result, acetic acid production quickly increased until about three days, and then the rate decreased.

Figure 1.

Batch fermentation profile of 10.0 g/L of sugars in hydrolyzed nipa sap by M. thermoacetica with full nutrient.

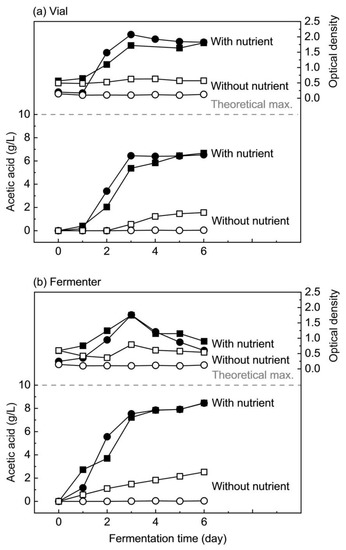

To gain first insights into the possible role of minor compounds in nipa sap as a nutrient source, fermentations with and without nutrients were compared in vials as well as in fermenters. Control experiments were also run using standard sugars in concentrations similar to the sugars present in hydrolyzed nipa sap. Figure 2 shows acetic acid production and cell growth from the fermentation of hydrolyzed nipa sap with and without nutrients as compared with standard sugars. The dotted line represents the theoretical maximum amount of acetic acid produced after total sugars are fully fermented which is 10 g/L.

Figure 2.

Comparison of acetic acid production and cell growth during fermentation in (a) vials and (b) fermenters of hydrolyzed nipa sap (square) and 1:1 mixture of glucose and fructose (circle) by M. thermoacetica; filled symbols: with full nutrient, open symbols: without nutrient.

First, with full nutrient supplementation (filled symbols), despite a day of the lag period in vials, the trends of acetic production from nipa sap and standard sugars were similar in vials and in fermenters in the first three days. After that, acetic acid concentration in the vial reached a plateau especially with standard sugars, while it continued to increase slightly in the fermenter. After six days of fermentation, acetic acid concentrations from vials with full nutrient were 6.4 g/L from standard sugars and 6.7 g/L from nipa sap, while in fermenters, they accounted for 8.4 g/L and 8.5 g/L, respectively. This difference is most probably due to the difference in the pH controlling system. In vials, although buffers were present, the pH gradually decreased as the acid was produced, especially after three days when it became way below the optimum pH of 6.5, resulting in only 80% substrate consumption and lower acetic acid concentration. In the fermenter, however, the pH was constantly kept at 6.5 by automatic filtration, allowing 100% substrate consumption and providing a higher acetic acid yield.

In terms of microbial growth with full nutrient, it was observed both in vials as well as in fermenters that the initial OD in nipa sap was higher than the starting OD in the broth with standard sugars. This is perhaps due to the presence of optically detectable elements in nipa sap. OD exponentially increased during the first three days in vials as well as in fermenters either for standard sugars or nipa sap, and cell densities at three days were similar, between 1.72 and 1.76, except for vial fermentation of standard sugars which showed an OD of 2.08. In vials, cell growth on standard sugars was slightly faster than for nipa sap, maybe because of the pH or some elements in nipa sap when mixed with the nutrients might have limited the growth. As opposed to that, cell growth was faster in nipa sap than in standard sugars when the fermentation was performed in the fermenter, but the maximum ODs after three days were the same. Since the initial ODs were different, this might mean that the microbes might have adapted their growth based on the initial cell density. After three days, OD reduced slowly in vials while the decrease was faster in the fermenter, most probably due to earlier substrate depletion.

Without nutrients, fermentation of standard sugars could not occur, and no cell growth was detected in vials and fermenters. These results confirm that M. thermoacetica actually needs essential nutrients for growth and acetic acid production. In contrast, slight increases in acetic acid concentration and OD were observed during the fermentation of hydrolyzed nipa sap without nutrients. In vials, a lag period of around two days was observed. Then, acid was gradually produced and reached 1.6 g/L in the fermenter after six days of fermentation. In fermenters, acetic acid production started from the beginning of fermentation without a lag period and reached 2.5 g/L towards the end. The difference in acetic acid production between vials and fermenters might be explained by the starting pH. In fermenters, the initial pH of 6.5 is already optimal, while in vials, the buffers set the pH at around 7.0, and concomitantly with the absence of external nutrients, the microorganisms in vials might have needed more time to adapt before growth and acetogenesis.

Maximum optical densities from nipa sap fermentation without supplementary nutrients were 0.63 in vials and 0.79 in fermenters, while they were negligible with standard sugars. Microbial growth with nipa sap as compared to no growth in standard sugar fermentation indicates that minor compounds in nipa sap could have sustained viability, metabolism, and growth of M. thermoacetica to some point. However, acetic acid production was relatively low, perhaps due to the absence or limitation of some nutrients available in nipa sap. For this reason, fermentations without each class of nutrient were performed so as to determine which one can be eliminated.

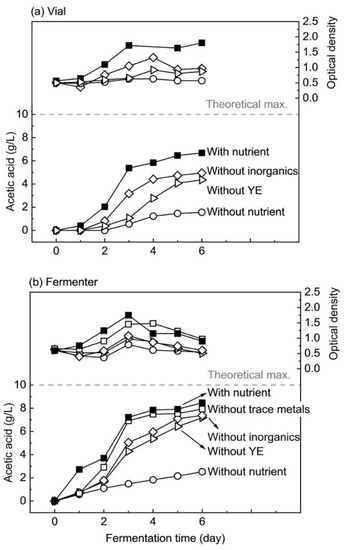

3.2.2. Fermentation of Hydrolyzed Nipa Sap without Trace Metals

Figure 3 reports acetic acid production and cell growth from the fermentation of hydrolyzed nipa sap without trace metals as compared with full nutrient supplementation as treated in the fermenter. Precisely, the trace metals in question are MgSO4·7H2O, Fe(NH4)2(SO4)2·6H2O, NiCl2·6H2O, ZnSO4·7H2O, and Na2SeO3.

Figure 3.

Comparison of acetic acid production and cell growth from fermentation of hydrolyzed nipa sap by M. thermoacetica in (a) vials and (b) fermenters with full nutrient (filled square), without trace metals (open square), without inorganics (open diamond), without yeast extract (open triangle), and without nutrient (open circle).

Nipa sap could be fermented without trace metals. Even if fermentation was slower than with full nutrient on the first day, it accelerated afterward and overall acetic acid production without trace metals accounting for 0.055 g/L/h was close to the one with full nutrient which was 0.059 g/L/h.

Although maximum optical density with trace metal was slightly lower than that with full nutrient, accounting for 1.5 and 1.7, respectively, acetic acid concentrations after six days of fermentation were not much different, corresponding to 7.9 and 8.5 g/L. Therefore, the above-mentioned metals are not required for the growth and activity of M. thermoacetica when nipa sap hydrolysate is used as substrate. Hence, the mineral compounds present in nipa sap could fulfill the microbial needs for trace metals.

In more detail, Table 3 compares the concentration of inorganic elements required for M. thermoacetica with their amount in nipa sap. It shows that six out of eight required trace elements are present in nipa sap. The concentrations of five elements in nipa sap that are magnesium Mg, Fe, Cl, Zn, Na, and N accounting for (4.4 ± 0.9) × 10−2, 5.9 × 10−3, 5.0 ± 2.8, 0.5 × 10−3, 1.0 ± 0.3 and 0.6 ± 0.1 g/L could largely cover the needs of M. thermoacetica that account for 2.5 × 10−3, 5.7 × 10−3, less than 0.24 × 10−3, 0.066 × 10−3, less than 1.0 × 10−3 and 0.7 g/L, respectively. This confirms that mineral compounds in nipa sap fulfilled most microbial requirements and can also explain why fermentation without trace metal occurred successfully. In the particular case of S, it is mainly brought by ammonium sulfate as a nitrogen source in the full nutrient condition and will be discussed in the next section.

Table 3.

Concentration of inorganics elements required for M. thermoacetica in full nutrient condition compared with their amount in nipa sap.

Whether Ni and Se are included in nipa sap is not certain yet. The device used for elemental composition in this study was not equipped for their quantification. However, a study reported the presence of Ni in nipa sap vinegar [24]. That said, if nipa sap does not have Ni and/or Se, and since fermentation without trace metal was successful, it might mean that these elements are not vital for M. thermoacetica or other trace elements in nipa sap might have played their role.

3.2.3. Fermentation of Hydrolyzed Nipa Sap without Inorganics

Total inorganics here are defined as the sum of trace minerals and ammonium sulfate which is an inorganic nitrogen source. The difference with the trace minerals-free condition is the further removal of inorganic nitrogen. The fermentation profile in the vial and fermenter without inorganic supplementation is shown in Figure 3 as open diamond, and the obtained acetic acid concentrations were 5.0 and 7.4 g/L, respectively, most probably due to a better pH control in the fermenter.

Trends of acetic acid production in vials and fermenters were similar despite the small lag period in the vial. In the fermenter, acetic acid was produced from the beginning of fermentation but in a slower manner than with full nutrient. Optical density remained more or less constant for two days. Rates of protein synthesis in clostridial cells starved for external nitrogen were reported to be lower than in non-starved cells [25]. Due to the non-addition of ammonium sulfate, less nitrogen was present in the broth without inorganic addition, as compared with full nutrient. This might explain the fact that cell growth was lower in fermentation without any inorganic supplement as compared with the one without trace metals and the one with full nutrient.

It was only after one day that cell growth was observed in the fermenter and OD reached 1.1 after three days. This resulted in an exponential increase in acetic acid concentration which attained 7.4 g/L after six days of fermentation. Such a value is not far from the value of 8.5 g/L with full nutrient but it took longer to reach without inorganic supplementation.

Interestingly, while growth ceased after three days in the fermenter, acetic acid continued to be produced gradually because the living cells present after three days could have still continued their metabolism even though cell multiplication did not happen anymore or happened but at a slower rate than cell lysis.

Quantitatively, as seen in Table 3, nipa sap contains 0.6 ± 0.1 g/L of nitrogen, and M. thermoacetica requires similar total amount with 0.2 g/L from ammonium sulfate and 0.5 g/L from yeast extract. This shows that nipa sap can somehow fill the nitrogen needs of M. thermoacetica even though a lag period was observed in the condition without inorganics. There was a delay and an adaptation period in that case because the nitrogen sources in nipa sap might not be as readily assimilable by the microorganism as the nitrogen provided by ammonium sulfate.

Sulfur (S) is an element brought mainly with ammonium sulfate in a rather high amount of 0.28 g/L. Since fermentation without inorganics was successful despite the lower available amount in nipa sap, it might imply that S is not necessarily required in such a high amount for M. thermoacetica.

3.2.4. Fermentation of Hydrolyzed Nipa Sap without Yeast Extract

Yeast extract is known to be an effective nitrogen source for bacterial cell growth stimulation and also a source of vitamins. Fermentation without yeast extract was performed to test whether the nitrogen and vitamins included in nipa sap can replace yeast extract supplementation. As seen in Table 3, and as mentioned earlier, the amount of nitrogen in nipa sap is equivalent to the requirements for M. thermoacetica.

In more detail, Figure 3 shows the fermentation profile when nipa sap was fermented without yeast extract. Fermentation kinetics in vials and fermenters were similar, with a lag phase of 2–3 days, followed by exponential growth and acetic acid production. In fermenters, trends in acetic acid production and microbial growth were comparable with those without inorganics. Similar to fermentation without inorganics and most probably for the same reasons, acetic acid continued to be produced even though optical density decreased after three days. Acetic acid of 7.2 g/L without yeast extract in the fermenter was, however, slightly lower than without inorganics after six days of fermentation, accounting for 7.4 g/L. A possible reason is that organic nitrogen and other elements brought by yeast extract were better at promoting microbial metabolism than inorganic nitrogen in ammonium sulfate under the amounts used in this study.

Yeast extract is one of the most expensive nutrients for microbial cultivation, especially for M. thermoacetica. Some research has been performed to find cheaper alternative nutrient sources [9]. This work demonstrates that even without yeast extract, cell growth and acetate production could occur when nipa sap is used as a substrate because the nitrogen and vitamins present in nipa sap could serve as nutrient sources for M. thermoacetica.

3.2.5. Nipa Sap as Nutrient Source for Minimal Medium Supplementation

Table 4 presents the summary of acetic acid fermentation of hydrolyzed nipa sap under different nutrient supplements and Table 5 compares the total number of additives used for fermentation with M. thermoacetica in this study and in the literature.

Table 4.

Summary of fermentation in vials and fermenters of 10 g/L hydrolyzed nipa sap and 10 g/L standard sugars by M. thermoacetica under different nutrient supplements after 6 days of fermentation.

Table 5.

Comparison of total number of supplements used for fermentation with M. thermoacetica.

Cell growth and acetic acid production were more affected by the elimination of nitrogen sources either inorganic as in ammonium sulfate or organic as in yeast extract than by the elimination of trace metals. Although it took a longer time than with full nutrient or without trace metals, fermentations without inorganics and without yeast extract provided similar acetic acid concentrations.

The removal of trace metals did not drastically affect fermentation as attested by the values in Table 4 because the minerals in nipa sap could be used as nutrients by M. thermoacetica. This is a great advantage for producing bioderived acetic acid in remote regions where commercial trace metals are not available. In more detail, the full nutrient formula reported in this study has five sorts of trace metals that are normally required to cultivate M. thermoacetica. One of Drake’s minimal media required even more mineral salts: 15–19 as reported in Table 5. Replacing those elements with only nipa sap can be extremely profitable and practical in an industrial setting.

Other researchers have previously attempted to define a minimal medium for M. thermoacetica [8,26,28]. Table 5 shows the total number of additives used in those studies as compared with this work. In Drake’s famous minimal media [8,26], 23 to 27 additives are still necessary. In a more recent work by Ehsanipor et al. [27], the medium was composed of 13 chemicals. In this work, however, the starting full nutrient included 8 elements and could be further reduced to 2 since nipa sap could be used as a carbon, nitrogen, vitamin, and mineral salt source.

While few publications have previously reported the use of nipa sap as a nutrient source for yeast fermentation [19,29], to the best of our knowledge, this is the first work demonstrating the capability of the anaerobic M. thermoacetica to grow and ferment nipa sap with minimal nutrient supplementation consisting only of two chemicals.

To gain more insights into the most economical nutrient condition, Table 1 compares the cost of supplementary nutrients per liter of media for each nutrient condition. First, with full nutrient, a liter of medium costs $1.7/L. Without trace metals, it is reduced to $1.6/L and further to $1.5/L without inorganics. The cheapest nutrient condition is without yeast extract at a price of $0.3/L. The unit price of yeast extract is in the same range as that of the other nutrients, but a higher concentration of yeast extract is required for the growth of M. thermoacetica, while the minerals are added in trace amounts. This explains the fact that yeast absorbs the major part of the nutrient cost. As seen in Table 3, nipa sap was fermented without yeast extract with a conversion efficiency of 72%, reducing by 80% the price of supplementary nutrients per ton of acetic acid produced from nipa sap as compared with the full nutrient.

In that sense, this study presents a double advantage in terms of cost saving as no external yeast extract is necessary, and nipa sap contains sugars that represent an inexpensive carbon source. Furthermore, cost savings will be significantly more important when nipa sap is hydrolyzed with oxalic acid. Indeed, we have previously demonstrated a cheaper alternative for hydrolysis by using oxalic acid as a catalyst [3,4,5]. Oxalic acid can also be converted to acetic acid by M. thermoacetica [3,4,5] and can, therefore, interfere with the material balance. For this reason, we have chosen enzymatic hydrolysis in this nutrient study to make sure that the obtained acetic acid comes only from the carbon in nipa sap. In an industrial setting though, oxalic acid hydrolysis is recommended to reduce cost.

Further enhancement of sugar uptake and growth by nutrient adaptation may also accelerate and improve fermentation without yeast extract and may consist of an extra cost saving for acetic acid production.

3.3. Comparison with Vinegar Process

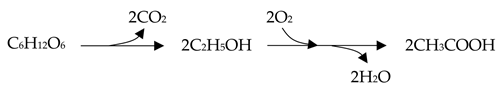

Saithong P. et al. [30] tried to optimize vinegar production from nipa sap without nutrients by using a two-step surface culture fermentation process including alcoholic fermentation for four weeks and vinegar production for 10 days, accounting for 38 days of fermentation in total. With such a long process, they obtained only 15–20% v/v conversion of ethanol into acetic acid, and thus a maximum of 7–10% sugar conversion to acetic acid.

This is due to the fact that the two-step vinegar production using yeasts and Acetobacters [31] releases two moles of CO2 during fermentation [32], as shown in Equation (4), while the homoacetogenic M. thermoacetica can directly convert all carbons in the substrate to acetic acid as a sole metabolite without by-products [33,34], as seen in Equation (5).

C6H12O6 → 3CH3COOH

Furthermore, the selectivity is low during the subsequent acetic acid fermentation by Acetobacter since lactic and other organic acids are by-produced [30]. Long fermentation times also lead to ethanol losses by evaporation [30].

Other research on vinegar production from different fruit concentrates showed ethanol-acetic acid conversion efficiency between 37 and 55% [35], and the subsequent ethanol-acetic acid efficiency was 45–55% [36] so the net sugar conversion efficiency to acetic acid varied between 21 and 24% only. In these studies, yeast Lalvin QA23 and yeast extract were used as nutrients for alcoholic and acetic acid fermentations, respectively [35,36].

In this process, although the sugar conversion efficiency to acetic acid without any nutrient was 25%, high efficiencies of 72%, 74%, and 79% were achieved without yeast extract, without inorganics, and without trace metals, respectively, thanks to the high selectivity of the homoacetogen M. thermoacetica and the absence of CO2 by-production. These values were attained in only six days of fermentation as opposed to 38 days for the vinegar production process and demonstrate the superiority of anaerobic acetic acid production by M. thermoacetica as compared with the vinegar process.

4. Conclusions

Minimizing the amount of nutrient supplementation to reduce cost has always been a point of concern in fermentation processes. In this work, the potential of nipa sap as a nutrient and carbon source was investigated, and the following conclusions can be made:

- ➢

- Natural nipa sap contains crucial inorganic elements and vitamins in addition to its high sugar content.

- ➢

- Using only one feedstock, namely nipa sap, covered all inorganic needs of M. thermoacetica. Nipa sap was demonstrated to be a good source of nutrients for M. thermoacetica in small as well as in higher fermentation scales and can reduce the number of media supplements from 8–27 chemicals to as few as 2. The most economical nutrient condition was without yeast extract. It could reduce the price of a liter of the medium by 83%, and the price of supplementary nutrients by 80% per ton of acetic acid produced.

- ➢

- Sugar conversion efficiencies to acetic acid in fermenters without additional inorganics or yeast extract are more than threefold those obtained from the vinegar process and in a much shorter fermentation time. Thus, anaerobic fermentation using M. thermoacetica and nipa sap can be economically viable to afford efficient commercial acetic acid production from renewable resources.

- ➢

- The results also open opportunities for inexpensive co-digestion or co-fermentation of nipa sap with other biomass resources where nipa sap will serve both as a carbon and nutrient source.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.R. and D.V.N.; methodology, H.R. and D.V.N.; validation, H.R.; formal analysis, data curation, writing—original draft preparation, D.V.N.; supervision, writing—review and editing, H.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST) as part of the Advanced Low Carbon Technology Research and Development Program (ALCA, grant number JPMJAL1012).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

This research was conducted with the smart guidance of Shiro Saka, Graduate School of Energy Science, Kyoto University, for which the authors are extremely grateful. The first author would like to acknowledge the financial support received from JICA under the AUN/SEED-Net Project for his PhD study. Furthermore, the authors are thankful to Pramila Tamunaidu from Malaysia-Japan International Institute of Technology, Universiti Teknologi Malaysia for providing the nipa sap samples used in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ijmker, H.M.; Gramblička, M.; Kersten, S.R.A.; van der Ham, A.G.J.; Schuur, B. Acetic acid extraction from aqueous solutions using fatty acids. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2014, 125, 256–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merli, G.; Becci, A.; Amato, A.; Beolchini, F. Acetic acid bioproduction: The technological innovation change. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 798, 149292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, D.V.; Sethapokin, P.; Rabemanolontsoa, H.; Minami, E.; Kawamoto, H.; Saka, S. Efficient production of acetic acid from nipa (Nypa fruticans) sap by Moorella thermoacetica (f. Clostridium thermoaceticum). Int. J. Green Technol. 2016, 2, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Rabemanolontsoa, H.; Kuninori, Y.; Saka, S. High conversion efficiency of Japanese cedar hydrolyzates into acetic acid by co-culture of Clostridium thermoaceticum and Clostridium thermocellum. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2016, 91, 1040–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabemanolontsoa, H.; Triwahyuni, E.; Takada, M. Consolidated bioprocessing of paper sludge to acetic acid by clostridial co-culture. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2021, 16, 100842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim-Castillo, P. Traditional Philippine vinegars and their role in shaping the culinary culture. In Authenticity in the Kitchen: Proceedings of the Oxford Symposium on Food and Cookery; Hosking, R., Ed.; Oxford Symposium: Devon, UK, 2006; pp. 295–306. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, M.M.; Cheryan, M. Acetate production by Clostridium thermoaceticum in corn steep liquor media. J. Ind. Microbiol. 1995, 15, 424–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundie, L.L.; Drake, H.L. Development of a minimally defined medium for the acetogen Clostridium thermoaceticum. J. Bacteriol. 1984, 159, 700–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witjitra, K.; Shah, M.M.; Cheryan, M. Effect of nutrient sources on growth and acetate production by Clostridium thermoaceticum. Enzym. Microb. Technol. 1996, 19, 322–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peralta, A.S. Nipa based products and agro-processing. In Proceedings of the 14th Agriculture and Fisheries Technology Forum and Product Exhibition Seminar Series, SM Megamall, Mandaluyong City, Philippines, 31 August 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, L.S.; Murphy, D.H. Use and management of nipa palm (Nypa fruticans, Arecaceae): A review. Econ. Bot. 1988, 42, 206–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Päivöke, A.E.A. Tapping practices and sap yields of the nipa palm (Nypa fruticans) in Papua New Guinea. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 1985, 13, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, Y.; Miyafuji, H.; Kawamoto, H.; Saka, S. Acetic acid fermentability with Clostridium thermoaceticum and Clostridium thermocellum of standard compounds found in beech wood as produced in hot-compressed water. J. Wood Sci. 2011, 57, 331–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sigma Aldrich. Prices of Nutrients for Microbial Growth Medium. Available online: https://www.sigmaaldrich.com/US/en (accessed on 11 October 2022).

- Van Die, J.; Tammes, P.M.L. Phloem exudation from monocotyledonous axes. In Transport in Plants I: Phloem Transport; Zimmermann, M.H., Milburn, J.A., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1975; pp. 196–222. [Google Scholar]

- Santiago-Urbina, J.; Ruíz-Terán, F. Microbiology and biochemistry of traditional palm wine produced around the world. Int. Food Res. J. 2014, 21, 1261–1269. [Google Scholar]

- Marquez, L.D.S.; Cabral, B.V.; Freitas, F.F.; Cardoso, V.L.; Ribeiro, E.J. Optimization of invertase immobilization by adsorption in ionic exchange resin for sucrose hydrolysis. J. Mol. Catal. B Enzym. 2008, 51, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulshrestha, S.; Tyagi, P.; Sindhi, V.; Yadavilli, K.S. Invertase and its applications—A brief review. J. Pharm. Res. 2013, 7, 792–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamunaidu, P.; Saka, S. Comparative study of nutrient supplements and natural inorganic components in ethanolic fermentation of nipa sap. J. Jpn. Inst. Energy 2013, 92, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saengkrajang, W.; Chaijan, M.; Panpipat, W. Physicochemical properties and nutritional compositions of nipa palm (Nypa fruticans Wurmb) syrup. NFS J. 2021, 23, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phetrit, R.; Chaijan, M.; Sorapukdee, S.; Panpipat, W. Characterization of nipa palm’s (Nypa fruticans Wurmb.) sap and syrup as functional food ingredients. Sugar Tech. 2020, 22, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorasin, T. A comparative study of the physicochemical, nutritional characteristics and microbiological contamination of fresh nipa palm (Nypa fruticans) sap. BUSCIJ 2018, 23, 1301–1316. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, V.D.; Rabemanolontsoa, H.; Saka, S. Sap from various palms as a renewable energy source for bioethanol production. Chem. Ind. Chem. Eng. 2016, 22, 355–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhtar, S.I.; Zakaria, F.; Ayob, M.A.; Siow, W.S.; Nurshahida, A.S.; Latiff, Z.A.A. Study on the nutritional values and customer acceptance of Lansium domesticum & Nephelium lappaceum newly fermented natural fruit vinegars in Malaysia. Asian Pac. J. Adv. Bus. Soc. Stud. 2016, 2, 402–413. [Google Scholar]

- Reardon, K.F.; Bailey, J.E. Effects of pH and added metabolites on bioconversions by immobilized non-growing Clostridium acetobutylicum. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 1989, 34, 825–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seifritz, C.; Daniel, S.L.; Gössner, A.; Drake, H.L. Nitrate as a preferred electron sink for the acetogen Clostridium thermoaceticum. J. Bacteriol. 1993, 175, 8008–8013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehsanipour, M.; Suko, A.V.; Bura, R. Fermentation of lignocellulosic sugars to acetic acid by Moorella thermoacetica. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 43, 807–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koesnandar; Ago, S.; Nishio, N.; Nagai, S. Production of extracellular 5-aminolevulinic acid by Clostridium thermoaceticum grown in minimal medium. Biotechnol. Lett. 1989, 11, 567–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chongkhong, S.; Puangpee, S. Alternative energy under the royal initiative of his majesty the king: Ethanol from nipa sap using isolated yeast. Songklanakarin J. Sci. Technol. 2018, 40, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Saithong, P.; Nitipan, S.; Permpool, J. Optimization of vinegar production from nipa (Nypa fruticans Wurmb.) sap using surface culture fermentation process. Appl. Food Biotechnol. 2019, 6, 193–200. [Google Scholar]

- Paivoke, A.; Adams, M.R.; Twiddy, D.R. Nipa palm vinegar in Papua New Guinea. Process Biochem. 1984, 19, 84–87. [Google Scholar]

- Cheryan, M. Acetic acid production. In Encyclopedia of Microbiology; Schaechter, M., Ed.; Academic Press: Oxford, UK, 2009; pp. 144–149. [Google Scholar]

- Fontaine, F.E.; Peterson, W.H.; McCoy, E.; Johnson, M.J.; Ritter, G.J. A new type of glucose fermentation by Clostridium thermoaceticum. J. Bacteriol. 1942, 43, 701–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koesnandar, A.; Nishio, N.; Nagai, S. Effects of trace metal ions on the growth, homoacetogenesis and corrinoid production by Clostridium thermoaceticum. J. Ferment. Bioeng. 1991, 71, 181–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, E.; Genisheva, Z.; Oliveira, J.M.; Teixeira, J.A.; Domingues, L. Vinegar production from fruit concentrates: Effect on volatile composition and antioxidant activity. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 54, 4112–4122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, E.; Vilanova, M.; Genisheva, Z.; Oliveira, J.M.; Teixeira, J.A.; Domingues, L. Systematic approach for the development of fruit wines from industrially processed fruit concentrates, including optimization of fermentation parameters, chemical characterization and sensory evaluation. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 62, 1043–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).