Epipolythiodioxopiperazines: From Chemical Architectures to Biological Activities and Ecological Significance—A Comprehensive Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Structural Diversity of ETPs

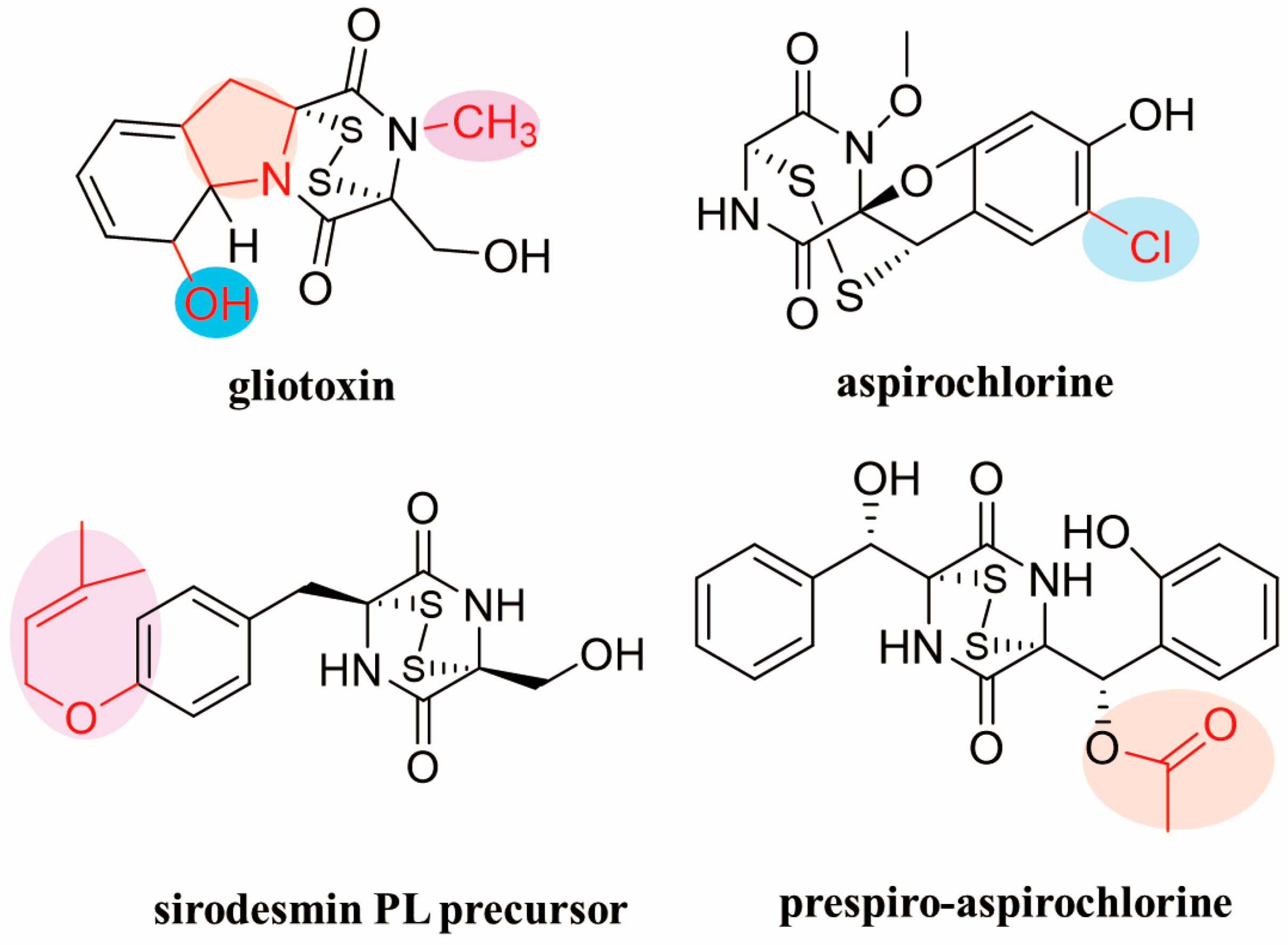

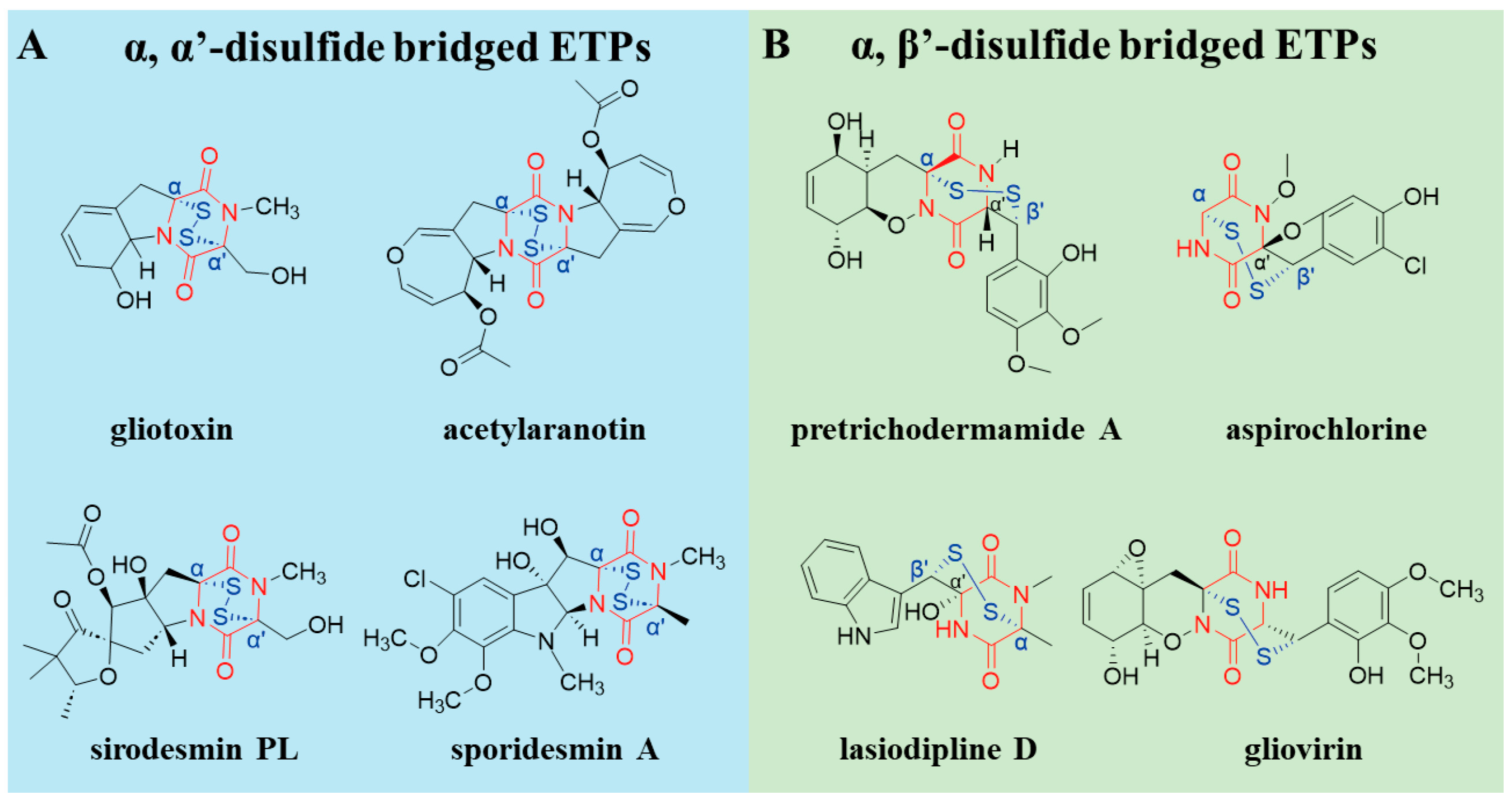

2.1. Core Diketopiperazine Scaffold and Sulfur Bridge Connectivity

2.2. Other Structural Modifications

3. Biosynthesis of ETPs

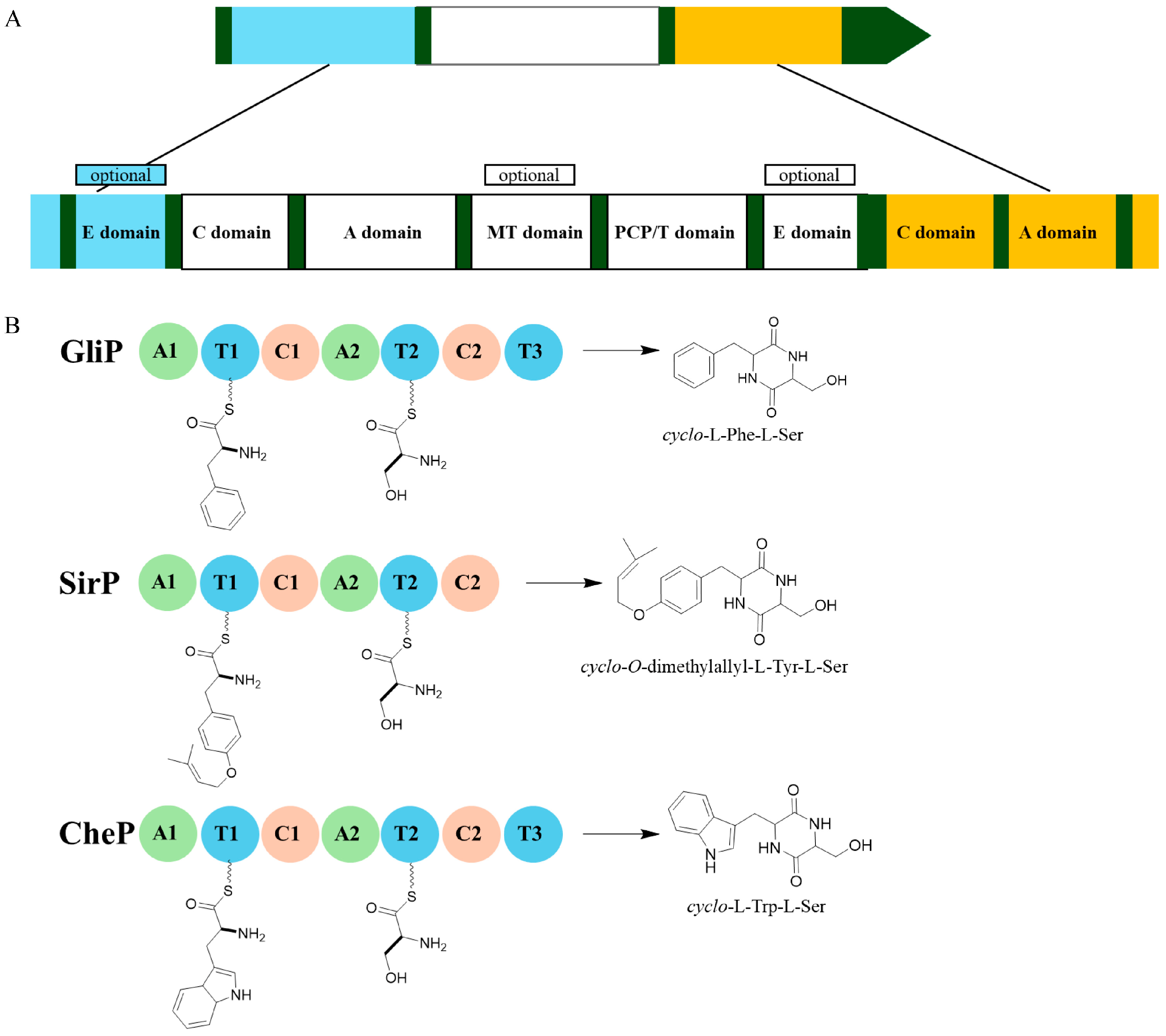

3.1. Initial Step: Assembly of the DKP Skeleton

3.2. Sulfur Incorporation and Oxidation

3.3. Tailoring Enzymes and Their Roles in Structural Diversification

3.4. Regulation of ETP Biosynthesis

4. The Biological Activity of ETPs

4.1. Cytotoxicity and Antitumor Activity

| Compound | Biological Activity | IC50 | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gliotoxin | breast cancer subtypes | IC50 = 0.1457–1.538 μM | [75] |

| Chetomin | NSCLC CSCs | IC50 = 1.6–22 nM | [77] |

| NSCLC non-CSCs | IC50 = 4.1–6.3 nM | [77] | |

| multiple myeloma cell | IC50 = 4.1 nM | [78] | |

| Chaetocochin J | colorectal cancer cell | IC50 = 0.5 μM | [79] |

| Pretrichodermamide B | lung cancer cells A549 | IC50 = 5.28–6.57 μM | [80] |

| prostate cancer cells DU145 | IC50 = 2.45 μM | ||

| colorectal cancer cells HCT116 | IC50 = 5.30 ± 1.07 μM | ||

| TAN-1496 A | murine and human tumor cell lines | IC50 = 0.016–0.072 μg/mL | [82] |

4.2. Antimicrobial Activity

| Compound Name | Pathogens | MIC/IC50 | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Verticillin D | S. aureus | MIC = 3–10 μg/mL | [85] |

| Glionitrin A | MRSA | MIC = 0.78 µg/mL | [86] |

| Chetracin B | MRSA | MIC = 0.7 µM, IC50 = 0.2 µM | [89] |

| Chetomin | C. albicans MRSA | MIC = 1.56–3.125 μg/mL MIC = 0.05 µg/mL | [44] |

| Acetylgliotoxin | C. albicans C. neoformans | MIC = 2.0 µg/mL MIC = 4.0 µg/mL | [93] |

| Aspirochlorine | azole-resistant C. albicans | IC50 = 0.028 µM | [21] |

4.3. Immunomodulatory Activity

5. The Ecological Significance of ETPs

5.1. Role in Fungal-Host Interactions

5.2. Competition and Symbiosis in Fungal Communities

6. Challenges and Future Prospects

6.1. Challenges in ETPs Research

6.2. Future Research Directions

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ETP | Epipolythiodioxopiperazines |

| DKP | Diketopiperazine |

| NRPSs | Nonribosomal peptide synthetases |

| FDA | U.S. Food and Drug Administration |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| IC50 | Half Maximum Inhibitory Concentration |

| MIC | Minimum Inhibitory Concentration |

References

- Luo, Z.; Yin, F.; Wang, X.; Kong, L. Progress in approved drugs from natural product resources. Chin. J. Nat. Med. 2024, 22, 195–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, D.J.; Cragg, G.M. Natural products as sources of new drugs over the nearly four decades from 01/1981 to 09/2019. J. Nat. Prod. 2020, 83, 770–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwasa, E.; Hamashima, Y.; Sodeoka, M. Epipolythiodiketopiperazine alkaloids: Total syntheses and biological activities. Isr. J. Chem. 2011, 51, 420–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, E.M. Epipolythiodioxopiperazine-Based natural products: Building blocks, biosynthesis and biological activities. ChemBioChem 2022, 23, e202200341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojarska, J.; Mieczkowski, A.; Ziora, Z.M.; Skwarczynski, M.; Toth, I.; Shalash, A.O.; Parang, K.; El-Mowafi, S.A.; Mohammed, E.H.M.; Elnagdy, S.; et al. Cyclic Dipeptides: The biological and structural landscape with special focus on the anti-cancer proline-based scaffold. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardiner, D.M.; Waring, P.; Howlett, B.J. The epipolythiodioxopiperazine (ETP) class of fungal toxins: Distribution, mode of action, functions and biosynthesis. Microbiology 2005, 151, 1021–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.; Li, Y.; Wei, P.-L.; Zhang, S.; Wang, D.; Fan, J.; Yin, W.-B. Novel epidithiodiketopiperazine derivatives in the mutants of the filamentous fungus Trichoderma hypoxylon. J. Fungi 2025, 11, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, T.R.; Williams, R.M. Epidithiodioxopiperazines. occurrence, synthesis and biogenesis. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2014, 31, 1376–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Ran, H.; Wei, P.-L.; Li, Y.; Liu, H.; Li, S.-M.; Hu, Y.; Yin, W.-B. Pretrichodermamide A biosynthesis reveals the hidden diversity of epidithiodiketopiperazines. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202217212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, M.; Winum, J.Y. The importance of sulfur-containing motifs in drug design and discovery. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 2022, 17, 501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.S.; Guo, Y.W. Epipolythiodioxopiperazines from fungi: Chemistry and bioactivities. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 2011, 11, 728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Q.; Song, H. Progress in gliotoxin research. Molecules 2025, 30, 3665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Limwachiranon, J.; Xu, F.; Xu, L.R.; Xiong, Z.Z.; Han, Y.; Guo, Y.J.; Zhang, N.; Scharf, D.H. Enzymatic dimerization of fungal natural products through intermolecular disulfide bridges. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2024, 366, 4422–4429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Hou, Y.; Yang, Q.; Li, X.; Wu, S. Structures and biological activities of diketopiperazines from marine organisms: A review. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Wei, P.L.; Yin, W.B. Formation of bridged disulfide in epidithiodioxopiperazines. ChemBioChem 2024, 25, e202300770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scharf, D.H.; Remme, N.; Heinekamp, T.; Hortschansky, P.; Brakhage, A.A.; Hertweck, C. Transannular disulfide formation in gliotoxin biosynthesis and its role in self-resistance of the human pathogen Aspergillus fumigatus. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 10136–10141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kremer, A.; Li, S.-M. A tyrosine O-prenyltransferase catalyses the first pathway-specific step in the biosynthesis of sirodesmin PL. Microbiology 2010, 156, 278–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.-J.; Yeh, H.-H.; Chiang, Y.-M.; Sanchez, J.F.; Chang, S.-L.; Bruno, K.S.; Wang, C.C.C. Biosynthetic pathway for the epipolythiodioxopiperazine acetylaranotin in Aspergillus terreus revealed by genome-based deletion analysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 7205–7213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, G.; Taylor, A.; Vining, L.C. Sporidesmins. Part VI. Isolation and structure of dehydrogliotoxin a metabolite of Penicillium terlikowskii. J. Chem. Soc. C 1966, 20, 1799–1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chankhamjon, P.; Boettger-Schmidt, D.; Scherlach, K.; Urbansky, B.; Lackner, G.; Kalb, D.; Dahse, H.M.; Hoffmeister, D.; Hertweck, C. Biosynthesis of the halogenated mycotoxin aspirochlorine in koji mold involves a cryptic amino acid conversion. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 13409–13413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Jiang, N.; Mei, Y.N.; Chu, Y.L.; Ge, H.M.; Song, Y.C.; Ng, S.W.; Tan, R.X. An antibacterial metabolite from Lasiodiplodia pseudotheobromae F2. Phytochemistry 2014, 100, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stipanovic, R.D.; Howell, C.R.; Hedin, P.A. Biosynthesis of gliovirin: Incorporation of L-phenylalanine (1-13C). J. Antibiot. 1994, 47, 942–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hai, Y.; Wei, M.-Y.; Wang, C.-Y.; Gu, Y.-C.; Shao, C.-L. The intriguing chemistry and biology of sulfur-containing natural products from marine microorganisms (1987–2020). Mar. Life Sci. Technol. 2021, 3, 488–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurita, D.; Sato, H.; Miyamoto, K.; Uchiyama, M. Mechanistic investigation of the degradation pathways of α–β/α–α bridged epipolythiodioxopiperazines (ETPs). J. Org. Chem. 2023, 88, 12797–12801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harms, H.; Orlikova, B.; Ji, S.; Nesaei-Mosaferan, D.; König, G.M.; Diederich, M. Epipolythiodiketopiperazines from the Marine Derived Fungus Dichotomomyces cejpii with NF-κB Inhibitory Potential. Mar. Drugs 2015, 13, 4949–4966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, M.; Zhang, X.; Huang, X.; Wang, H.; Anjum, K.; Gu, Q.; Zhu, T.; Zhang, G.; Li, D. Irregularly bridged epipolythiodioxopiperazines and related analogues: Sources, structures, and biological activities. J. Nat. Prod. 2020, 83, 2045–2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Takada, K.; Takemoto, Y.; Yoshida, M.; Nogi, Y.; Okada, S.; Matsunaga, S. Gliotoxin analogues from a marine-derived fungus, Penicillium sp., and their cytotoxic and histone methyltransferase inhibitory activities. J. Nat. Prod. 2012, 75, 111–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chi, L.-P.; Li, X.-M.; Li, L.; Li, X.; Wang, B.-G. Cytotoxic Thiodiketopiperazine derivatives from the deep sea-derived fungus Epicoccum nigrum SD-388. Mar. Drugs 2020, 18, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bathelt, C.M.; Ridder, L.; Mulholland, A.J.; Harvey, J.N. Mechanism and structure-reactivity relationships for aromatic hydroxylation by cytochrome P450. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2004, 2, 2998–3005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, M.R.; Shepherd, S.A.; Cronin, V.A.; Micklefield, J. Recent advances in methyltransferase biocatalysis. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2017, 37, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steffan, N.; Grundmann, A.; Yin, W.B.; Kremer, A.; Li, S.M. Indole prenyltransferases from fungi: A new enzyme group with high potential for the production of prenylated indole derivatives. Curr. Med. Chem. 2009, 16, 218–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamazaki, H. Exploration of marine natural resources in Indonesia and development of efficient strategies for the production of microbial halogenated metabolites. J. Nat. Med. 2022, 76, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Süssmuth, R.D.; Mainz, A. Nonribosomal peptide synthesis-principles and prospects. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 3770–3821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kries, H. Biosynthetic engineering of nonribosomal peptide synthetases. J. Pept. Sci. 2016, 22, 564–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, S.; Garcia-Gonzalez, E.; Mainz, A.; Hertlein, G.; Heid, N.C.; Mösker, E.; van den Elst, H.; Overkleeft, H.S.; Genersch, E.; Süssmuth, R.D. Paenilamicin: Structure and biosynthesis of a hybrid nonribosomal peptide/polyketide antibiotic from the bee pathogen Paenibacillus larvae. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 10821–10825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marahiel, M.A.; Stachelhaus, T.; Mootz, H.D. Modular peptide synthetases involved in nonribosomal peptide synthesis. Chem. Rev. 1997, 97, 2651–2674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, H.; Zou, Y. Biosynthesis and metabolic engineering of fungal non-ribosomal peptides. Synth. Biol. J. 2024, 5, 571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rausch, C.; Hoof, I.; Weber, T.; Wohlleben, W.; Huson, D.H. Phylogenetic analysis of condensation domains in NRPS sheds light on their functional evolution. BMC Evol. Biol. 2007, 7, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velkov, T.; Lawen, A. Mapping and molecular modeling of S-adenosyl-L-methionine binding sites in N-methyltransferase domains of the multifunctional polypeptide cyclosporin synthetase. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 1137–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marion, A.; Groll, M.; Scharf, D.H.; Scherlach, K.; Glaser, M.; Sievers, H.; Schuster, M.; Hertweck, C.; Brakhage, A.A.; Antes, I.; et al. Gliotoxin biosynthesis: Structure, mechanism, and metal promiscuity of carboxypeptidase GliJ. ACS Chem. Biol. 2017, 12, 1874–1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balibar, C.J.; Walsh, C.T. GliP, a multimodular nonribosomal peptide synthetase in Aspergillus fumigatus, makes the diketopiperazine scaffold of gliotoxin. Biochemistry 2006, 45, 15029–15038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scharf, D.H.; Heinekamp, T.; Remme, N.; Hortschansky, P.; Brakhage, A.A.; Hertweck, C. Biosynthesis and function of gliotoxin in Aspergillus fumigatus. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2011, 93, 467–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardiner, D.M.; Cozijnsen, A.J.; Wilson, L.M.; Pedras, M.S.C.; Howlett, B.J. The sirodesmin biosynthetic gene cluster of the plant pathogenic fungus Leptosphaeria maculans. Mol. Microbiol. 2004, 53, 1307–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, P.; Liu, H.; Wu, Q.; Meng, Q.; Qu, K.; Yin, X.; Wang, M.; Zhao, X.; Qi, J.; Meng, Y.; et al. Investigation of chetomin as a lead compound and its biosynthetic pathway. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2022, 106, 3093–3102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.-L.; Chiang, Y.-M.; Yeh, H.-H.; Wu, T.-K.; Wang, C.C.C. Reconstitution of the early steps of gliotoxin biosynthesis in Aspergillus nidulans reveals the role of the monooxygenase GliC. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2013, 23, 2155–2157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scharf, D.H.; Dworschak, J.D.; Chankhamjon, P.; Scherlach, K.; Heinekamp, T.; Brakhage, A.A.; Hertweck, C. Reconstitution of enzymatic carbon-sulfur bond formation reveals detoxification-like strategy in fungal toxin biosynthesis. ACS Chem. Biol. 2018, 13, 2508–2512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jefferies, H.; Coster, J.; Khalil, A.; Bot, J.; McCauley, R.D.; Hall, J.C. Glutathione. ANZ J. Surg. 2003, 73, 517–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scherlach, K.; Kuttenlochner, W.; Scharf, D.H.; Brakhage, A.A.; Hertweck, C.; Groll, M.; Huber, E.M. Structural and mechanistic insights into C−S bond formation in gliotoxin. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 14188–14194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Fan, J.; Zhang, P.; Hu, Y.; Liu, X.; Li, S.-M.; Yin, W.-B. New insights into the disulfide bond formation enzymes in epidithiodiketopiperazine alkaloids. Chem. Sci. 2021, 12, 4132–4138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, J.; Ran, H.; Wei, P.L.; Li, Y.; Liu, H.; Li, S.M.; Yin, W.B. An ortho-quinone methide mediates disulfide migration in the biosynthesis of epidithiodiketopiperazines. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202304252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, M.; Mokkawes, T.; Cao, Y.; de Visser, S.P. Mechanism of the oxidative ring-closure reaction during gliotoxin biosynthesis by cytochrome P450 GliF. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 8567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, H.; Scharf, A.H.; Heinekamp, T.; Brakhage, A.A.; Hertweck, C. Opposed effects of enzymatic gliotoxin N- and S-methylations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 11674–11679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, W.; Liu, T.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, W. The toxic mechanism of gliotoxins and biosynthetic strategies for toxicity prevention. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 13510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Johnson, R.M.; Li, B. A Permissive amide N-Methyltransferase for dithiolopyrrolones. ACS Catal. 2023, 13, 1899–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Wei, P.-L.; Li, Y.; Ren, Z.; Fan, J.; Yin, W.-B. Functional diversification of epidithiodiketopiperazine methylation and oxidation towards pathogenic fungi. Mycology 2025, 16, 1418–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duell, E.R.; Glaser, M.; Le Chapelain, C.; Antes, I.; Groll, M.; Huber, E.M. Sequential inactivation of gliotoxin by the S-methyltransferase Tmta. ACS Chem. Biol. 2016, 11, 1082–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Wang, P.; Ma, C.; Li, K.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhang, G.; Che, Q.; Zhu, T.; et al. Characterization and structural analysis of a versatile aromatic prenyltransferase for imidazole-containing diketopiperazines. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Liu, J.; Yang, B. Catalytic mechanism and engineering of aromatic prenyltransferase: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 313, 144214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolf, J.D.; Poulter, C.D. Tyrosine O-prenyltransferase SirD catalyzes S-, C-, and N-prenylations on tyrosine and tryptophan derivatives. ACS Chem. Biol. 2013, 8, 2707–2714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamazaki, H.; Rotinsulu, H.; Narita, R.; Takahashi, R.; Namikoshi, M. Induced production of halogenated epidithiodiketopiperazines by a marine-derived Trichoderma cf. brevicompactum with sodium halides. J. Nat. Prod. 2015, 78, 2319–2321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamazaki, H.; Takahashi, O.; Kirikoshi, R.; Yagi, A.; Ogasawara, T.; Bunya, Y.; Rotinsulu, H.; Uchida, R.; Namikoshi, M. Epipolythiodiketopiperazine and trichothecene derivatives from the NaI-containing fermentation of marine-derived Trichoderma cf. brevicompactum. J. Antibiot. 2020, 73, 559–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Wan, W. Acetylation in the regulation of autophagy. Autophagy 2023, 19, 379–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drazic, A.; Myklebust, L.M.; Ree, R.; Arnesen, T. The world of protein acetylation. Biochim. Biop. Acta (BBA)-Proteins Proteom 2016, 1864, 1372–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amrine, C.S.M.; Huntsman, A.C.; Doyle, M.G.; Burdette, J.E.; Pearce, C.J.; Fuchs, J.R.; Oberlies, N.H. Semisynthetic derivatives of the verticillin class of natural products through acylation of the C11 hydroxy group. ACS Med. Chem. 2021, 12, 625–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yu, W.; Lu, Y.; Wu, Y.; Ouyang, Z.; Tu, Y.; He, B. Epigenetic regulation of fungal secondary metabolism. J. Fungi 2024, 10, 648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolan, S.K.; O’Keeffe, G.; Jones, G.W.; Doyle, S. Resistance is not futile: Gliotoxin biosynthesis, functionality and utility. Trends Microbiol. 2015, 23, 419–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bok, J.W.; Chung, D.; Balajee, S.A.; Marr, K.A.; Andes, D.; Nielsen, K.F.; Frisvad, J.C.; Kirby, K.A.; Keller, N.P. GliZ, a transcriptional regulator of gliotoxin biosynthesis, contributes to Aspergillus fumigatus virulence. Infect. Immun. 2006, 74, 6761–6768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.-L.; Ye, W.; Zhu, M.-Z.; Kong, Y.-L.; Li, S.-N.; Liu, S.; Zhang, W.-M. Interaction of a novel Zn2Cys6 transcription factor DcGliz with promoters in the gliotoxin biosynthetic gene cluster of the deep-sea-derived fungus Dichotomomyces cejpii. Biomolecules 2019, 10, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cramer, R.A.; Ries, L.N.A.; Pardeshi, L.; Dong, Z.; Tan, K.; Steenwyk, J.L.; Colabardini, A.C.; Ferreira Filho, J.A.; de Castro, P.A.; Silva, L.P.; et al. The Aspergillus fumigatus transcription factor RglT is important for gliotoxin biosynthesis and self-protection, and virulence. PLoS Pathog. 2020, 16, e1008645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, A.P.; de Castro, P.A.; Colabardini, A.C.; Moraes, M.; Horta, M.A.C.; Knowles, S.L.; Raja, H.A.; Oberlies, N.H.; Koyama, Y.; Ogawa, M.; et al. Regulation of gliotoxin biosynthesis and protection in Aspergillus species. PLoS Genet. 2022, 18, e1009965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Li, K.; Yu, J.; Ma, C.; Che, Q.; Zhu, T.; Li, D.; Pfeifer, B.A.; Zhang, G. Cyclo-diphenylalanine production in Aspergillus nidulans through stepwise metabolic engineering. Metab. Eng. 2024, 82, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Wang, X.; Song, F.; Peng, Y.; Wang, Q. Advances in metabolic engineering for the production of aromatic chemicals. Chin. J. Biotechnol. 2021, 37, 1771–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzin, V.; Galili, G. New insights into the shikimate and aromatic amino acids biosynthesis pathways in plants. Mol. Plant 2010, 3, 956–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, F.; Han, Y.; LI, J.; Yanjun, L.; Xu, Q.; Chen, N.; Xie, X. Metabolic engineering of aromatic amino acids in Escherichia coli. Chin. J. Bioprocess Eng. 2017, 15, 32–39,85. [Google Scholar]

- Nambiar, S.S.; Ghosh, S.S.; Saini, G.K. Gliotoxin triggers cell death through multifaceted targeting of cancer-inducing genes in breast cancer therapy. Comput. Biol. Chem. 2024, 112, 108170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, L.L.; Ho, P.; Toh, J.; Tan, E.-K. Chetomin rescues pathogenic phenotype of LRRK2 mutation in drosophila. Aging 2020, 12, 18561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, S.; Wang, X.; Du, Q.; Gong, H.; Yang, Y.; Wang, T.; Wu, N.; Liu, X.; Li, W.; Zhao, C. Chetomin, a Hsp90/HIF1α pathway inhibitor, effectively targets lung cancer stem cells and non-stem cells. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2020, 21, 698–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viziteu, E.; Grandmougin, C.; Goldschmidt, H.; Seckinger, A.; Hose, D.; Klein, B.; Moreaux, J. Chetomin, targeting HIF-1α/p300 complex, exhibits antitumour activity in multiple myeloma. Br. J. Cancer 2016, 114, 519–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, S.; Yin, J.; Yan, S.; Hu, P.; Huang, J.; Zhang, G.; Wang, F.; Tong, Q.; Zhang, Y. Chaetocochin J, an epipolythiodioxopiperazine alkaloid, induces apoptosis and autophagy in colorectal cancer via AMPK and PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathways. Bioorg. Chem. 2021, 109, 104693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, R.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, X.; Yang, L.; Liu, J.; Wightman, S.M.; Lv, L.; Liu, Z.; Wang, C.-Y.; Zhao, C. Identification of marine natural product Pretrichodermamide B as a STAT3 inhibitor for efficient anticancer therapy. Mar. Life Sci. Technol. 2023, 5, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; He, N.; Liu, Q.; Li, R.; Yang, L.; Kang, W.; Zhang, X.; Xu, X.; Yao, G.; Wang, P.; et al. Structural optimization of marine natural product pretrichodermamide B for the treatment of colon cancer by targeting the JAK/STAT3 signaling pathway. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 67, 10783–10794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funabashi, Y.; Horiguchi, T.; Iinuma, S.; Tanida, S.; Harada, S. TAN-1496 A, C and E, diketopiperazine antibiotics with inhibitory activity against mammalian DNA topoisomerase I. J. Antibiot. 1994, 47, 1202–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, G.; Zhang, Z.; Niu, X.; Zhu, D. Secondary Metabolites from Fungi Microsphaeropsis spp.: Chemistry and Bioactivities. J. Fungi 2023, 9, 1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierre, H.C.; Patel, D.J.; Raja, H.A.; Darveaux, B.A.; Patel, K.I.; Mardiana, L.; Longcake, A.; Hall, M.J.; Probert, M.R.; Pearce, C.J.; et al. Studies on the epipolythiodioxopiperazine alkaloid verticillin D: Scaled production, streamlined purification, and absolute configuration. Phytochemistry 2025, 236, 114492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.-J.; Kim, C.-J.; Bae, K.S.; Kim, Y.-H.; Kim, W.-G. Bionectins A−C, epidithiodioxopiperazines with anti-MRSA activity, from Bionectra byssicola F120. J. Nat. Prod. 2006, 69, 1816–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.B.; Kwon, H.C.; Lee, C.-H.; Yang, H.O. Glionitrin A, an antibiotic−antitumor metabolite derived from competitive interaction between abandoned mine microbes. J. Nat. Prod. 2009, 72, 248–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Zhao, Z.; Qi, X.; Tang, S.; Wang, Q.; Zhu, T.; Gu, Q.; Liu, M.; Li, J. Identification of epipolythiodioxopiperazines HDN-1 and chaetocin as novel inhibitor of heat shock protein 90. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 5263–5274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Li, D.; Luan, Y.; Gu, Q.; Zhu, T. Cytotoxic metabolites from the antarctic psychrophilic fungus Oidiodendron truncatum. J. Nat. Prod. 2012, 75, 920–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebead, G.A.; Overy, D.P.; Berrué, F.; Kerr, R.G. Westerdykella reniformis sp. nov., producing the antibiotic metabolites melinacidin IV and chetracin B. IMA Fungus 2012, 3, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, C.; García-Domínguez, P.; Álvarez, R.; de Lera, A.R. Bispyrrolidinoindoline epi(poly)thiodioxopiperazines (BPI-ETPs) and simplified mimetics: Structural characterization, bioactivities, and total synthesis. Molecules 2022, 27, 7585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, D.; Hannah, D.E.; Rahman, R.; Taylor, A. The growth of Bacillus subtilis in media containing chetomin, sporidesmin, and gliotoxin. Can. J. Microbiol. 1967, 13, 1451–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, W.-L.; Le, X.; Li, H.-J.; Yang, X.-L.; Chen, J.-X.; Xu, J.; Liu, H.-L.; Wang, L.-Y.; Wang, K.-T.; Hu, K.-C.; et al. Exploring the chemodiversity and biological activities of the secondary metabolites from the marine fungus Neosartorya pseudofischeri. Mar. Drugs 2014, 12, 5657–5676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaturvedi, V.; Coleman, J.J.; Ghosh, S.; Okoli, I.; Mylonakis, E. Antifungal activity of microbial secondary metabolites. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e25321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroll, M.A.-S.F.; Bachelerie, F.; Thomas, D.; Friguet, B.; Conconi, M. The secondary fungal metabolite gliotoxin targets proteolytic activities of the proteasome. Chem. Biol. 1999, 6, 689–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujimoto, H.; Sumino, M.; Okuyama, E.; Ishibashi, M. Immunomodulatory constituents from an ascomycete, Chaetomium seminudum. J. Nat. Prod. 2004, 67, 98–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Castro Patrícia, A.; Delbaje, E.; Freitas Migliorini, I.L.D.; Pupo Monica, T.; Mondal Muhammad Shafiul, A.; Steffen, K.; Rokas, A.; Dolan Stephen, K.; Goldman Gustavo, H. Fungal mitochondria govern both gliotoxin biosynthesis and self-protection. mBio 2025, 16, e02401–e02425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pombo, M.A.; Rosli, H.G.; Maiale, S.; Elliott, C.; Stieben, M.E.; Romero, F.M.; Garriz, A.; Ruiz, O.A.; Idnurm, A.; Rossi, F.R. Unveiling the virulence mechanism of Leptosphaeria maculans in the Brassica napus interaction: The key role of sirodesmin PL in the induction of cell death. J. Exp. Bot. 2025, 76, 1767–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedras, M.S.C.; Yu, Y. Stress-driven discovery of metabolites from the phytopathogenic fungus Leptosphaeria maculans: Structure and activity of leptomaculins A–E. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2008, 16, 8063–8071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardiner, D.M.; Howlett, B.J. Bioinformatic and expression analysis of the putative gliotoxin biosynthetic gene cluster of Aspergillus fumigatus. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2005, 248, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeilinger, S.; Gruber, S.; Bansal, R.; Mukherjee, P.K. Secondary metabolism in Trichoderma–chemistry meets genomics. Fungal Biol. Rev. 2016, 30, 74–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.-c.; Liu, R.; Li, H.; An, Z.-p.; Zhou, F. Gliotoxins isolated from endophyic Penicillium sp. of astragali radix and their antimicrobial activity. Chin. J. Exp. Tradit. Med. Formulae 2017, 23, 68–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Xu, X.; Yin, W.-B. Genome mining of Epicoccum dendrobii reveals diverse antimicrobial natural products. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2025, 73, 6691–6701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, J.; Wang, J.; Zhang, X.Y.; Nong, X.H.; Qi, S.H. New furanone derivatives and alkaloids from the co-culture of marine-derived fungi Aspergillus sclerotiorum and Penicillium citrinum. Chem. Biodivers. 2017, 14, e1600327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, G.; Ran, H.; Fan, J.; Keller, N.P.; Liu, Z.; Wu, F.; Yin, W.-B. Fungal-fungal cocultivation leads to widespread secondary metabolite alteration requiring the partial loss-of-function VeA1 protein. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabo6094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.-H.; Hu, Y.-C.; Sun, B.-D.; Yu, M.; Niu, S.-B.; Guo, Z.; Zhang, X.-Y.; Zhang, T.; Ding, G.; Zou, Z.-M. Highly photosensitive poly-sulfur-bridged chetomin analogues from Chaetomium cochliodes. Org. Lett. 2018, 20, 1806–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, Q.; Jia, M.; Li, H.; Shi, T.; Xu, Y.; Zhao, T.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, P.; Xia, X. Epipolythiodioxopiperazines: From Chemical Architectures to Biological Activities and Ecological Significance—A Comprehensive Review. Fermentation 2025, 11, 700. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation11120700

Zhang Q, Jia M, Li H, Shi T, Xu Y, Zhao T, Zhang L, Zhao P, Xia X. Epipolythiodioxopiperazines: From Chemical Architectures to Biological Activities and Ecological Significance—A Comprehensive Review. Fermentation. 2025; 11(12):700. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation11120700

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Qingqing, Mingyang Jia, Hongyi Li, Tingting Shi, Ying Xu, Taili Zhao, Lixin Zhang, Peipei Zhao, and Xuekui Xia. 2025. "Epipolythiodioxopiperazines: From Chemical Architectures to Biological Activities and Ecological Significance—A Comprehensive Review" Fermentation 11, no. 12: 700. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation11120700

APA StyleZhang, Q., Jia, M., Li, H., Shi, T., Xu, Y., Zhao, T., Zhang, L., Zhao, P., & Xia, X. (2025). Epipolythiodioxopiperazines: From Chemical Architectures to Biological Activities and Ecological Significance—A Comprehensive Review. Fermentation, 11(12), 700. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation11120700