Metabolic and Safety Characterization of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum Strains Isolated from Traditional Rye Sourdough

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Strains

2.2. Safety Assessment

2.2.1. Hemolytic Activity

2.2.2. Antibiotic Susceptibility

2.3. Enzymatic, Biochemical, and Fermentative Properties of L. plantarum Strains

2.3.1. Enzymatic Activity

2.3.2. Carbohydrate Utilization

2.3.3. Rye Sourdough Fermentation and Analyses

2.4. Quantification of Exopolysaccharides

2.5. Effect of Aflatoxin B1 on Fermentative Properties of L. plantarum Strains

2.6. Aflatoxin B1 Binding Ability

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Hemolytic Activity and Antibiotic Susceptibility

3.2. Enzymatic Activity Profiles

3.3. Carbohydrate Metabolism Profiles

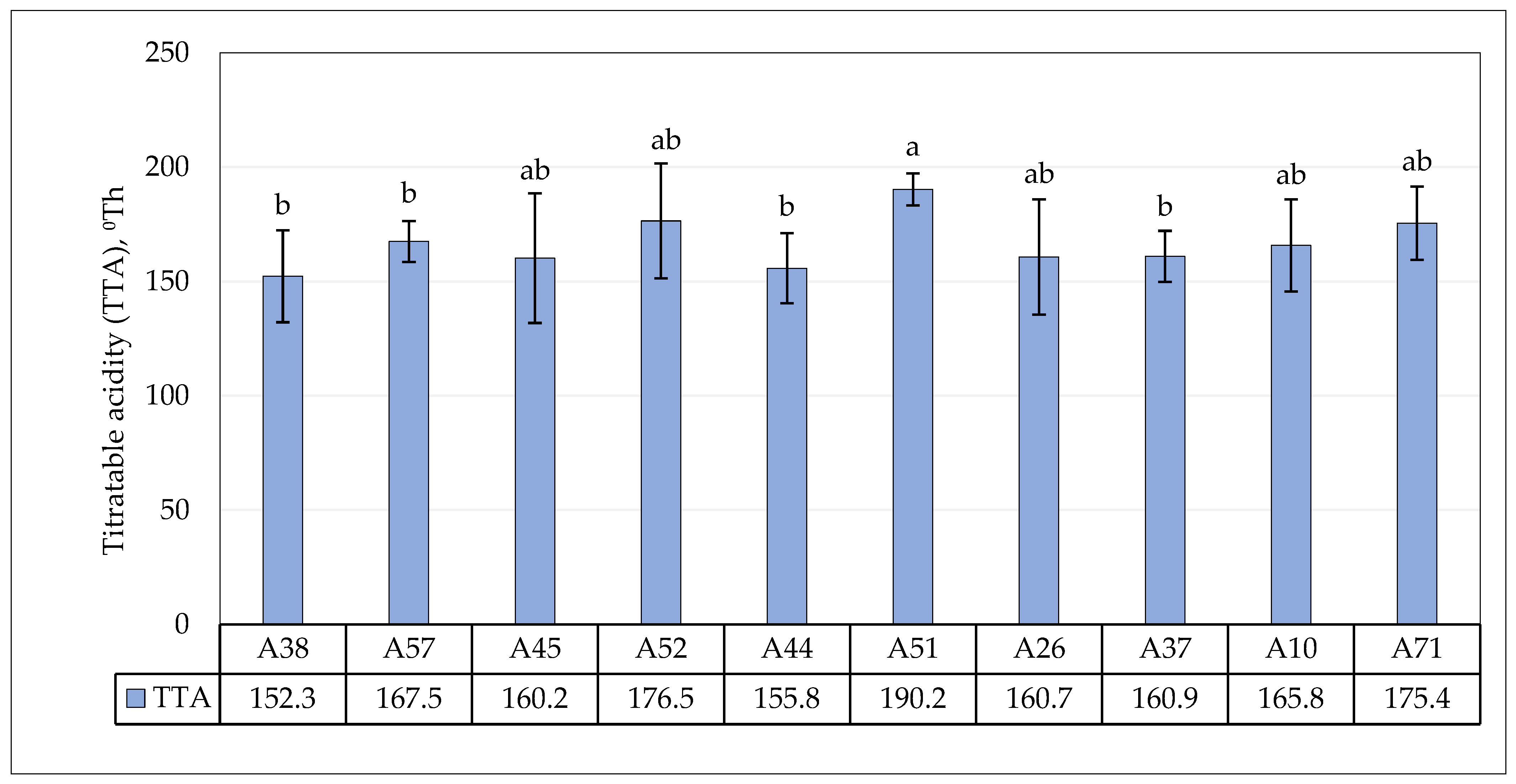

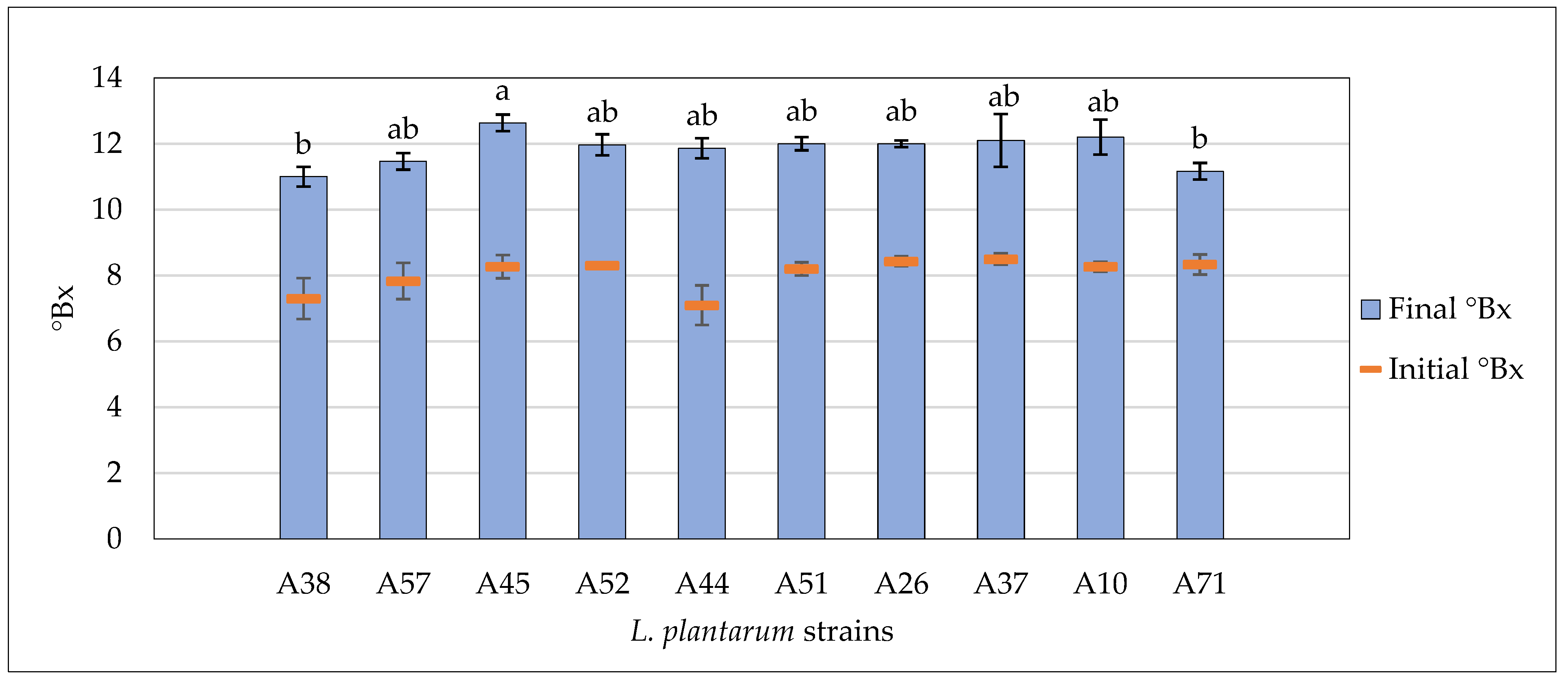

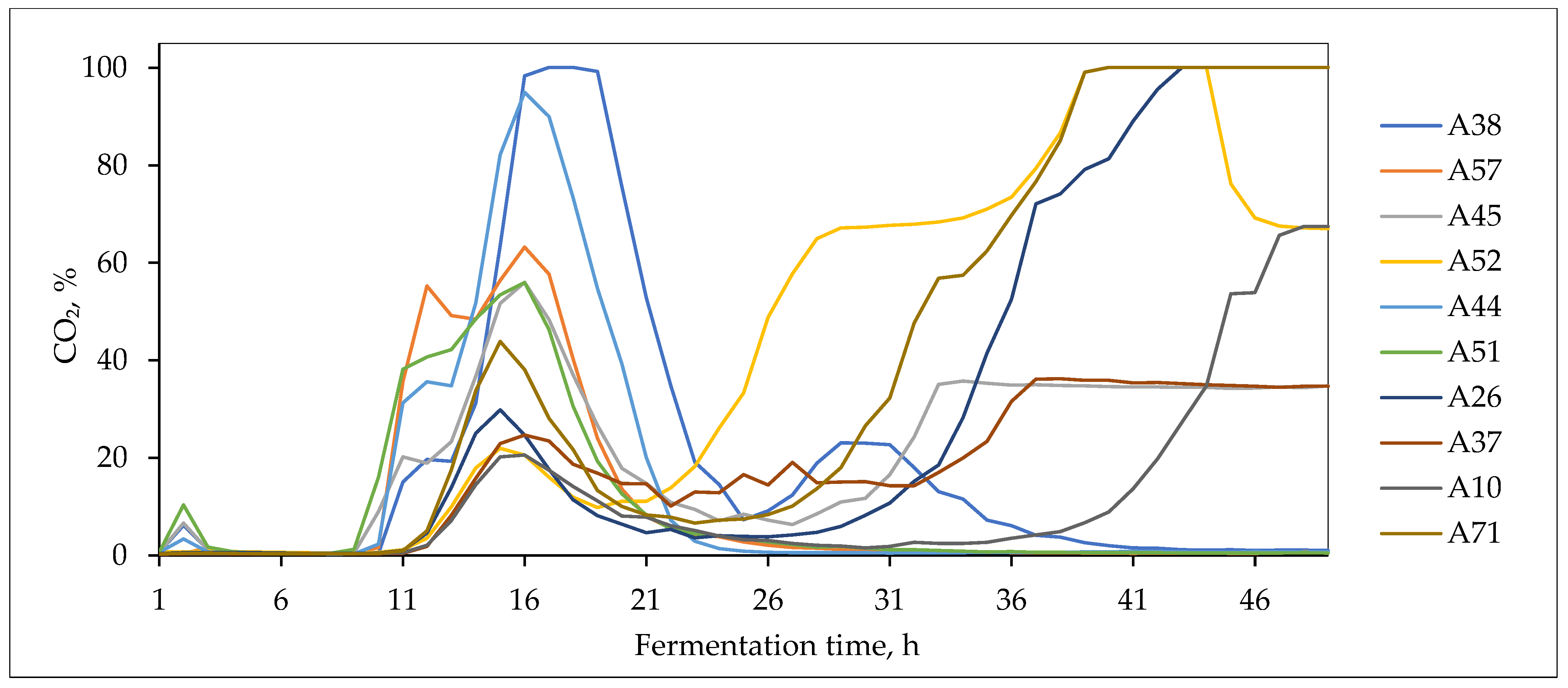

3.4. Fermentative Properties of L. plantarum Strains

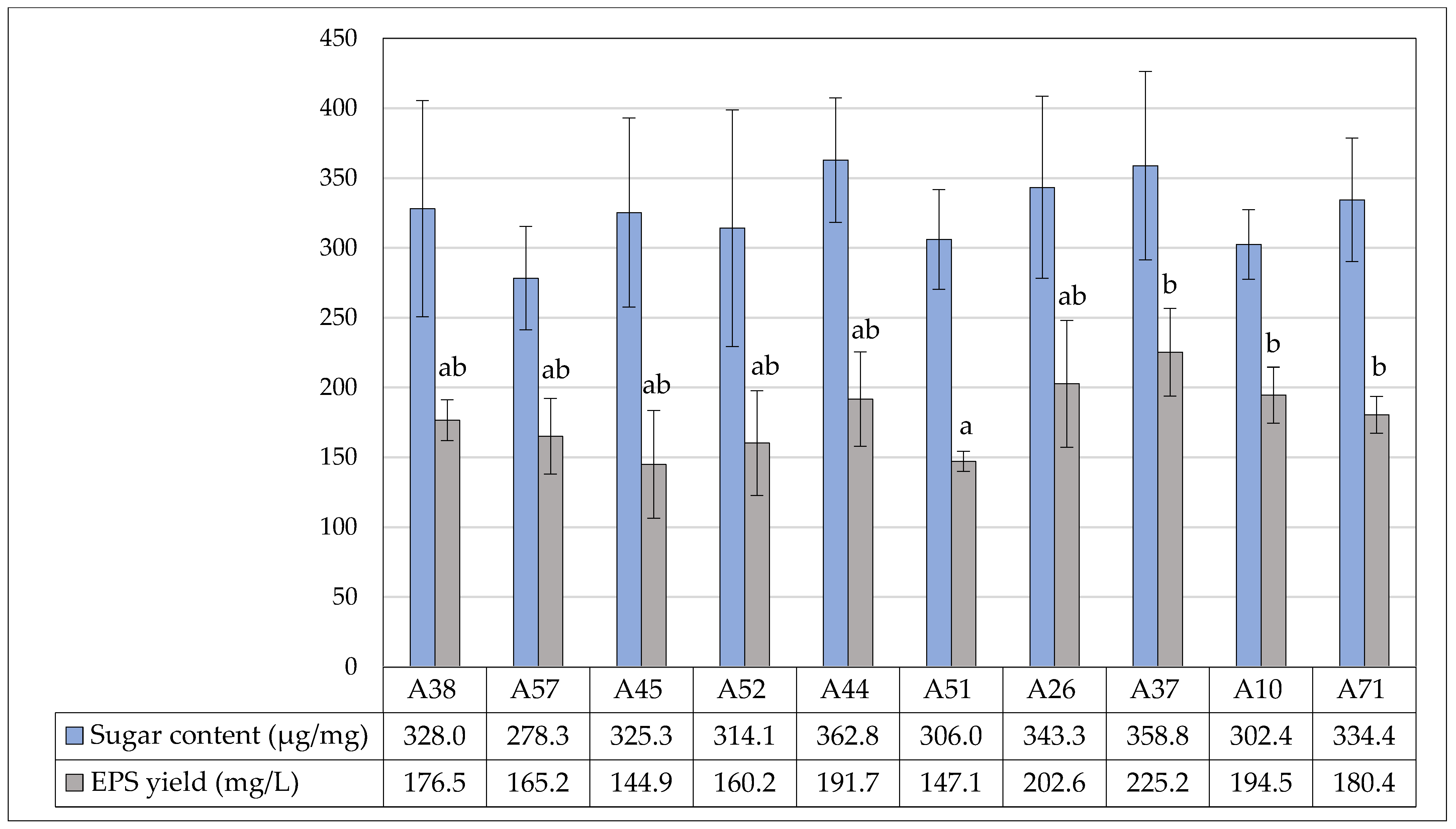

3.5. Exopolysaccharide Yield and Quantitative Sugar Content

3.6. Influence of Aflatoxin B1 on the Carbohydrate Fermentation Profiles of L. plantarum

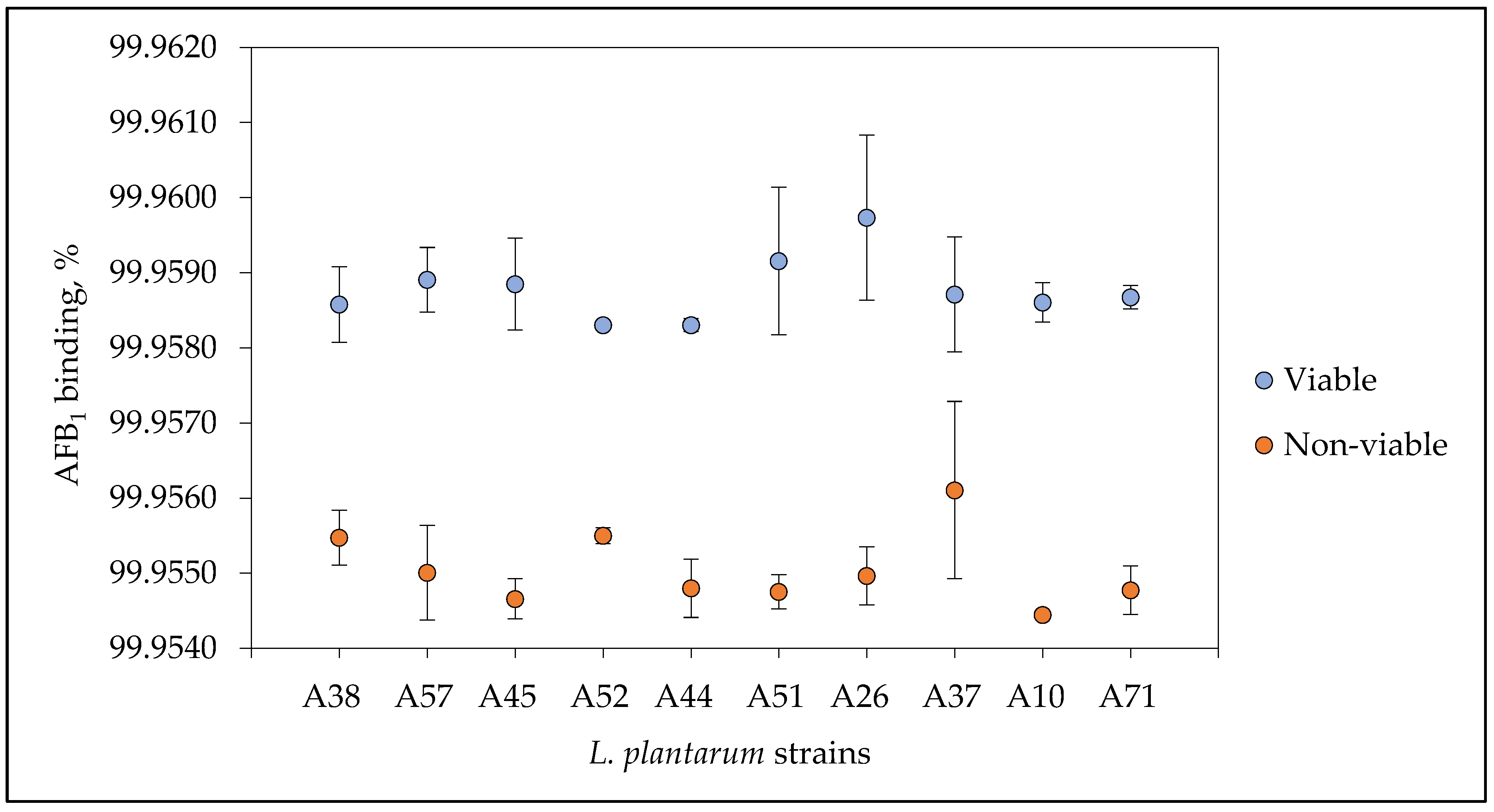

3.7. Aflatoxin B1 Binding Capacity

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Filannino, P.; Di Cagno, R.; Gobbetti, M. Metabolic and functional paths of lactic acid bacteria in plant foods: Get out of the labyrinth. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2018, 49, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gänzle, M.G.; Zheng, J. Lifestyles of sourdough lactobacilli–Do they matter for microbial ecology and bread quality? Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2019, 302, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siezen, R.J.; Tzeneva, V.A.; Castioni, A.; Wels, M.; Phan, H.T.K.; Rademaker, J.L.W.; Starrenburg, M.J.C.; Kleerebezem, M.; Van Hylckama Vlieg, J.E.T. Phenotypic and genomic diversity of Lactobacillus plantarum strains isolated from various environmental niches. Environ. Microbiol. 2010, 12, 758–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, B.; Yin, R.; Li, X.; Cui, S.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, J.; Chen, W. Comparative Genomic Analysis of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum Isolated from Different Niches. Genes 2021, 12, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleerebezem, M.; Boekhorst, J.; van Kranenburg, R.; Molenaar, D.; Kuipers, O.P.; Leer, R.; Tarchini, R.; Peters, S.A.; Sandbrink, H.M.; Fiers, M.W.E.J.; et al. Complete genome sequence of Lactobacillus plantarum WCFS1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 1990–1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corsetti, A.; Valmorri, S. Lactic Acid Bacteria. Lactobacillus spp.: Lactobacillus plantarum. In Encyclopedia of Dairy Sciences (Second Edition); Fuquay, J.W., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2011; pp. 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martino, M.E.; Bayjanov, J.R.; Caffrey, B.E.; Wels, M.; Joncour, P.; Hughes, S.; Gillet, B.; Kleerebezem, M.; van Hijum, S.A.F.T.; Leulier, F. Nomadic lifestyle of Lactobacillus plantarum revealed by comparative genomics of 54 strains isolated from different habitats. Environ. Microbiol. 2016, 18, 4974–49889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buntin, N.; Hongpattarakere, T.; Ritari, J.; Douillard, F.P.; Paulin, L.; Boeren, S.; Shetty, S.A.; de Vos, W.M. An Inducible Operon Is Involved in Inulin Utilization in Lactobacillus plantarum Strains, as Revealed by Comparative Proteogenomics and Metabolic Profiling. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2017, 83, e02402-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Wang, M.; Zheng, Y.; Miao, K.; Qu, X. The Carbohydrate Metabolism of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 13452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, K.; Ameur, H.; Polo, A.; Di Cagno, R.; Rizzello, C.G.; Gobbetti, M. Thirty years of knowledge on sourdough fermentation: A systematic review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 108, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abarquero, D.; Bodelón, R.; Manso, C.; Rivero, P.; Fresno, J.M.; Tornadijo, M.E. Effect of autochthonous starter and non-starter cultures on the physicochemical, microbiological and sensorial characteristics of Castellano cheese. Int. J. Dairy Technol. 2023, 77, 234–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capozzi, V.; Spano, G. Food microbial biodiversity and “microbes of protected origin”. Front. Microbiol. 2011, 2, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chessa, L.; Paba, A.; Daga, E.; Dupré, I.; Piga, C.; Di Salvo, R.; Mura, M.; Addis, M.; Comunian, R. Autochthonous Natural Starter Cultures: A Chance to Preserve Biodiversity and Quality of Pecorino Romano PDO Cheese. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ripari, V. Techno-Functional Role of Exopolysaccharides in Cereal-Based, Yogurt-Like Beverages. Beverages 2019, 5, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bangar, S.P.; Sharma, N.; Kumar, M.; Ozogul, F.; Purewal, S.S.; Trif, M. Recent developments in applications of lactic acid bacteria against mycotoxin production and fungal contamination. Food Biosci. 2021, 44, 101444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutter, L.; Kuzina, A.; Andreson, H. Genotypic Stability of Lactic Acid Bacteria in Industrial Rye Bread Sourdoughs Assessed by ITS-PCR Analysis. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EFSA Panel on Additives and Products or Substances used in Animal Feed (FEEDAP); Rychen, G.; Aquilina, G.; Azimonti, G.; Bampidis, V.; de Lourdes Bastos, M.; Bories, G.; Chesson, A.; Cocconcelli, P.S.; Flachowsky, G.; et al. Guidance on the characterization of microorganisms used as feed additives or as production organisms. EFSA J. 2018, 16, 5206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collar, C.; Armero, E. Millet-Wheat Mixed Breads: Impact of Sour Dough Addition on the Enhancement of the Physical Profile of Heat-Moisture Treated Matrices. Int. J. Food Eng. 2019, 5, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 2173:2003; Fruit and Vegetable Products—Determination of Soluble Solids—Refractometric Method. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2003. Available online: http://www.iso.org/iso/catalogue_detail.htm?csnumber=35851 (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Kavitake, D.; Devi, P.B.; Singh, S.P.; Shetty, P.H. Characterization of a novel galactan produced by Weissella confusa KR780676 from an acidic fermented food. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2016, 86, 681–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogura, I.; Sugiyama, M.; Tai, R.; Mano, H.; Matsuzawa, T. Optimization of microplate-based phenol-sulfuric acid method and application to the multi-sample measurements of cellulose nanofibers. Anal. Biochem. 2023, 681, 115329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutic, M.; Banina, A. Influence of aflatoxin B1 on gas production by lactic acid bacteria. J. Environ. Pathol. Toxicol. Oncol. 1990, 10, 149–153. [Google Scholar]

- Casarotti, S.N.; Carneiro, B.M.; Todorov, S.D.; Nero, L.A.; Rahal, P.; Penna, A.L.B. In vitro assessment of safety and probiotic potential characteristics of Lactobacillus strains isolated from water buffalo mozzarella cheese. Ann. Microbiol. 2017, 67, 289–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO/WHO. Food Safety Risk Analysis: A Guide for National Food Safety Authorities. 2006. Available online: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/43718/9789251056042_eng.pdf;jsessionid=689C4D54F8646357776C37326910DD2A?sequence=1 (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- Abdel Tawab, F.I.; Abd Elkadr, M.H.; Sultan, A.M.; Hamed, E.O.; El-Zayat, A.S.; Ahmed, M.N. Probiotic potentials of lactic acid bacteria isolated from Egyptian fermented food. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 16601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, H.-Y.; Liao, Y.-C.; Lin, S.-H.; Lin, J.-S.; Lee, C.-C.; Watanabe, K. Safety Assessment of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum TWK10 Based on Whole-Genome Sequencing, Phenotypic, and Oral Toxicity Analysis. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nami, Y.; Panahi, B.; Jalaly, H.M.; Rostampour, M.; Hejazi, M.A. Probiotic Characterization of LAB isolated from Sourdough and Different Traditional Dairy Products Using Biochemical, Molecular and Computational Approaches. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2025, 17, 1014–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ou, D.; Ling, N.; Wang, X.; Zou, Y.; Dong, J.; Zhang, D.; Shen, Y.; Ye, Y. Safety Assessment of One Lactiplantibacillus plantarum Isolated from the Traditional Chinese Fermented Vegetables—Jiangshui. Foods 2022, 11, 2177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasundaradevi, R.; Sarvajith, M.; Divyashree, S.; Deepa, N.; Achar, P.N.; Sreenivasa, M.Y. Tropical fruit-derived Lactiplantibacillus as potential probiotic and antifungal agents against Fusarium oxysporum. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Wang, H.; Lin, X.; Liang, H.; Zhang, S.; Chen, Y.; Ji, C. Probiotic properties of Lactobacillus plantarum and application in prebiotic gummies. LWT 2023, 174, 114357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iosca, G.; Fugaban, J.I.I.; Özmerih, S.; Wätjen, A.P.; Kaas, R.S.; Hà, Q.; Shetty, R.; Pulvirenti, A.; De Vero, L.; Bang-Berthelsen, C.H. Exploring the Inhibitory Activity of Selected Lactic Acid Bacteria against Bread Rope Spoilage Agents. Fermentation 2023, 9, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Cisneros, Y.M.; Ponce-Alquicira, E. Antibiotic Resistance in Lactic Acid Bacteria. In Antimicrobial Resistance—A Global Threat; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anisimova, E.; Gorokhova, I.; Karimullina, G.; Yarullina, D. Alarming antibiotic resistance of lactobacilli isolated from probiotic preparations and dietary supplements. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vannuffel, P.; Cocito, C. Mechanism of Action of Streptogramins and Macrolides. Drugs 1996, 51, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imperial, I.C.V.J.; Ibana, J.A. Addressing the Antibiotic Resistance Problem with Probiotics: Reducing the Risk of Its Double-Edged Sword Effect. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mingeot-Leclercq, M.P.; Glupczynski, Y.; Tulkens, P.M. Aminoglycosides: Activity and Resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1999, 43, 727–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikodinoska, I.; Heikkinen, J.; Moran, C.A. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Data for Six Lactic Acid Bacteria Tested against Fifteen Antimicrobials. Data 2022, 8, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefańska, I.; Kwiecień, E.; Jóźwiak-Piasecka, K.; Garbowska, M.; Binek, M.; Rzewuska, M. Antimicrobial Susceptibility of Lactic Acid Bacteria Strains of Potential Use as Feed Additives-The Basic Safety and Usefulness Criterion. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 687071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swenson, J.M.; Facklam, R.R.; Thornsberry, C. Antimicrobial susceptibility of vancomycin-resistant Leuconostoc, Pediococcus, and Lactobacillus species. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1990, 34, 543–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Li, F.; Zhang, M.; Xia, Y.; Ai, L.; Wang, G. Effect of D-Ala-Ended Peptidoglycan Precursors on the Immune Regulation of Lactobacillus plantarum Strains. Front. Immunol. 2022, 12, 825825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chokesajjawatee, N.; Santiyanont, P.; Chantarasakha, K.; Kocharin, K.; Thammarongtham, C.; Lertampaiporn, S.; Vorapreeda, T.; Srisuk, T.; Wongsurawat, T.; Jenjaroenpun, P.; et al. Safety Assessment of a Nham Starter Culture Lactobacillus plantarum BCC9546 via Whole-genome Analysis. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 10241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flórez, A.B.; Egervärn, M.; Danielsen, M.; Tosi, L.; Morelli, L.; Lindgren, S.; Mayo, B. Susceptibility of Lactobacillus plantarum Strains to Six Antibiotics and Definition of New Susceptibility–Resistance Cutoff Values. Microb. Drug Resist. 2006, 12, 252–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gueimonde, M.; Sánchez, B.; de los Reyes-Gavilán, C.G.; Margolles, A. Antibiotic resistance in probiotic bacteria. Front. Microbiol. 2013, 4, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Gao, J.; Wang, B.; Huo, D.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Shao, Y. Whole-genome sequencing reveals the mechanisms for evolution of streptomycin resistance in Lactobacillus plantarum. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 101, 2867–2874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kieliszek, M.; Pobiega, K.; Piwowarek, K.; Kot, A.M. Characteristics of the Proteolytic Enzymes Produced by Lactic Acid Bacteria. Molecules 2021, 26, 1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunji, E.R.S.; Mierau, I.; Hagting, A.; Poolman, B.; Konings, W.N. The proteolytic systems of lactic acid bacteria. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 1996, 70, 187–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maske, B.L.; de Melo Pereira, G.V.; Vale, A.d.S.; de Carvalho Neto, D.P.; Karp, S.G.; Viesser, J.A.; Lindner, J.D.D.; Pagnoncelli, M.G.; Soccol, V.T.; Soccol, C.R. A review on enzyme-producing lactobacilli associated with the human digestive process: From metabolism to application. Enzym. Microb. Technol. 2021, 149, 109836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flórez, A.B.; Vázquez, L.; Rodríguez, J.; Mayo, B. Phenotypic and Safety Assessment of the Cheese Strain Lactiplantibacillus plantarum LL441, and Sequence Analysis of its Complete Genome and Plasmidome. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 24, 605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.; So, Y.J.; Jung, W.H.; Kim, T.-R.; Sohn, M.; Jeong, Y.-J.; Imm, J.-Y. Lactiplantibacillus plantarum LM1001 Improves Digestibility of Branched-Chain Amino Acids in Whey Proteins and Promotes Myogenesis in C2C12 Myotubes. Food Sci. Anim. Resour. 2024, 44, 951–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broadbent, J.R.; Cai, H.; Larsen, R.L.; Hughes, J.E.; Welker, D.L.; De Carvalho, V.G.; Tompkins, T.A.; Ardö, Y.; Vogensen, F.; De Lorentiis, A.; et al. Genetic diversity in proteolytic enzymes and amino acid metabolism among Lactobacillus helveticus strains. J. Dairy Sci. 2011, 94, 4313–4328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobbetti, M.; Rizzello, C.G.; Di Cagno, R.; De Angelis, M. How the sourdough may affect the functional features of leavened baked goods. Food Microbiol. 2014, 37, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gänzle, M.G.; Loponen, J.; Gobbetti, M. Proteolysis in sourdough fermentations: Mechanisms and potential for improved bread quality. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2008, 19, 513–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicchi, C.; Leri, M.; Bucciantini, M.; Galli, V.; Guerrini, S.; Jiménez-Ortas, Á.; Ceacero-Heras, D.; Martínez-Augustín, O.; Pazzagli, L.; Luti, S. Sourdough Breads Made with Selected Lactobacillus Strains and Spelt Flour Contain Peptides That Positively Impact Intestinal Barrier. Foods 2025, 14, 3184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paventi, G.; Di Martino, C.; Crawford, T.W., Jr.; Iorizzo, M. Enzymatic activities of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum: Technological and functional role in food processing and human nutrition. Food Biosci. 2024, 61, 104944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengupta, S.; Datta, M.; Datta, S. Chapter 5-β-Glucosidase: Structure, function and industrial applications. In Glycoside Hydrolases; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2023; pp. 97–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokni, Y.; Abouloifa, H.; Bellaouchi, R.; Hasnaoui, I.; Gaamouche, S.; Lamzira, Z.; Salah, R.B.E.N.; Saalaoui, E.; Ghabbour, N.; Asehraou, A. Characterization of β-glucosidase of Lactobacillus plantarum FSO1 and Candida pelliculosa L18 isolated from traditional fermented green olive. J. Genet. Eng. Biotechnol. 2021, 19, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michlmayr, H.; Kneifel, W. β-Glucosidase activities of lactic acid bacteria: Mechanisms, impact on fermented food and human health. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2014, 352, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Martín, F.; Seseña, S.; Izquierdo, P.M.; Martín, R.; Palop, M.L. Screening for glycosidase activities of lactic acid bacteria as a biotechnological tool in oenology. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012, 28, 1423–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, S.-H.; Jeon, H.-L.; Yang, S.-J.; Sim, M.-H.; Kim, Y.-J.; Lee, N.-K.; Paik, H.-D. Probiotic lactic acid bacteria isolated from traditional Korean fermented foods based on β-glucosidase activity. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2018, 27, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeon, H.-L.; Lee, N.-K.; Yang, S.-J.; Kim, W.-S.; Paik, H.-D. Probiotic characterization of Bacillus subtilis P223 isolated from kimchi. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2017, 26, 1641–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhai, X.; Wu, K.; Ji, R.; Zhao, Y.; Lu, J.; Yu, Z.; Huang, J. Structure and Function Insight of the α-Glucosidase QsGH13 From Qipengyuania seohaensis sp. SW-135. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 849585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okuyama, M.; Saburi, W.; Mori, H.; Kimura, A. α-Glucosidases and α-1,4-glucan lyases: Structures, functions, and physiological actions. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2016, 73, 2727–2751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, G.; Cao, Y.; Xiao, J.; Sheng, G.; Lu, J. The Mechanisms of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum J6-6 against Iso-α-Acid Stress and Its Application in Sour Beer Production. Syst. Microbiol. Biomanufacturing 2024, 4, 1018–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Ryu, B.H.; Kim, J.; Yoo, W.; An, D.R.; Kim, B.-Y.; Kwon, S.; Lee, S.; Wang, Y.; Kim, K.K.; et al. Characterization of a novel SGNH-type esterase from Lactobacillus plantarum. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 96, 560–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.; Jung, S.-R.; Lee, S.-Y.; Lee, N.-K.; Paik, H.-D.; Lim, S.-I. Lactobacillus plantarum Strain Ln4 Attenuates Diet-Induced Obesity, Insulin Resistance, and Changes in Hepatic mRNA Levels Associated with Glucose and Lipid Metabolism. Nutrients 2018, 10, 643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, N.; Yin, B.; Fang, D.; Jiang, T.; Fang, S.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, H.; Wang, G.; Chen, W. Effects of Lactobacillus plantarum CCFM0236 on hyperglycaemia and insulin resistance in high-fat and streptozotocin-induced type 2 diabetic mice. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2016, 121, 1727–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muganga, L.; Liu, X.; Tian, F.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, H.; Chen, W. Screening for lactic acid bacteria based on antihyperglycaemic and probiotic potential and application in synbiotic set yoghurt. J. Funct. Foods 2015, 16, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.; Luo, J.; Zuo, F.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, H.; Chen, S. Screening for potential novel probiotic Lactobacillus strains based on high dipeptidyl peptidase IV and α-glucosidase inhibitory activity. J. Funct. Foods 2016, 20, 486–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, H.; Abdullah; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, M.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, H.; Xi, Y.; Cai, H.; Feng, F. Screening of novel potential antidiabetic Lactobacillus plantarum strains based on in vitro and in vivo investigations. LWT 2021, 139, 110526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gökmen, G.G.; Sarıyıldız, S.; Cholakov, R.; Nalbantsoy, A.; Baler, B.; Aslan, E.; Düzel, A.; Sargın, S.; Göksungur, Y.; Kışla, D. A novel Lactiplantibacillus plantarum strain: Probiotic properties and optimization of the growth conditions by response surface methodology. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2024, 40, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A.A.; Ismail, S.A. Production of antifungal N-acetyl-β-glucosaminidase chitinolytic enzyme using shrimp byproducts. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2021, 34, 102027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuhren, J.; Rösch, C.; Napel, M.T.; Schols, H.A.; Kleerebezem, M. Synbiotic matchmaking in Lactobacillus plantarum: Substrate Screening and Gene-Trait Matching to Characterize Strain-Specific Carbohydrate Utilization. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2020, 86, e01081-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žugić-Petrović, T.D.; Joković, N.; Savić, D.S. The evolution of lactic acid bacteria community during the development of mature sourdough. Acta Period. Technol. 2009, 40, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, M.R.A.; Wolfrum, G.; Stolz, P.; Ehrmann, M.A.; Vogel, R.F. Monitoring the growth of Lactobacillus species during a rye flour fermentation. Food Microbiol. 2001, 18, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siepmann, F.B.; de Almeida, B.S.; Waszczynskyj, N.; Spier, M.R. Influence of temperature and of starter culture on biochemical characteristics and the aromatic compounds evolution on type II sourdough and wheat bread. LWT 2019, 108, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrancken, G.; Rimaux, T.; Weckx, S.; Leroy, F.; De Vuyst, L. Influence of Temperature and Backslopping Time on the Microbiota of a Type I Propagated Laboratory Wheat Sourdough Fermentation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 77, 2716–2726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corsetti, A.; Gobbetti, M.; De Marco, B.; Balestrieri, F.; Paoletti, F.; Russi, L.; Rossi, J. Combined Effect of Sourdough Lactic Acid Bacteria and Additives on Bread Firmness and Staling. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2000, 48, 3044–3051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiele, C.; Gänzle, M.G.; Vogel, R.F. Contribution of Sourdough Lactobacilli, Yeast, and Cereal Enzymes to the Generation of Amino Acids in Dough Relevant for Bread Flavor. Cereal Chem. 2002, 79, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banu, I.; Vasilean, I.; Aprodu, I. Effect of Select Parameters of the Sourdough Rye Fermentation on the Activity of Some Mixed Starter Cultures. Food Biotechnol. 2011, 25, 275–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurtshuk, P.J. Medical Microbiology, 4th ed.; Baron, S., Ed.; University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston: Galveston, TX, USA, 1996; Chapter 4. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK7919/ (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Wang, Y.; Wu, J.; Lv, M.; Shao, Z.; Hungwe, M.; Wang, J.; Bai, X.; Xie, J.; Wang, Y.; Geng, W. Metabolism Characteristics of Lactic Acid Bacteria and the Expanding Applications in Food Industry. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 612285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wehrle, K.; Arendt, E.K. Rheological Changes in Wheat Sourdough During Controlled and Spontaneous Fermentation. Cereal Chem. 1998, 75, 882–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spicher, G.; Rabe, E.; Sommer, R.; Stephan, H. Die Mikroflora des Sauerteiges. Z. Für Lebensm.-Unters. Und Forsch. 1981, 173, 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coda, R.; Xu, Y.; Moreno, D.S.; Mojzita, D.; Nionelli, L.; Rizzello, C.; Katina, K. Performance of Leuconostoc citreum FDR241 during wheat flour sourdough type I propagation and transcriptional analysis of exopolysaccharides biosynthesis genes. Food Microbiol. 2018, 76, 164–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, D.; Gabriel, V.; Vayssier, Y.; Fontagné-Faucher, C. Simultaneous HPLC Determination of Sugars, Organic Acids and Ethanol in Sourdough Process. LWT 2002, 35, 407–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Settanni, L.; Ventimiglia, G.; Alfonzo, A.; Corona, O.; Miceli, A.; Moschetti, G. An integrated technological approach to the selection of lactic acid bacteria of flour origin for sourdough production. Food Res. Int. 2013, 54, 1569–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stehlik-Tomas, V.; Grba, S. Application of Starter-cultures for Baked Goods. FTB-Food Technol. Biotechnol. 1995, 33, 161–165. Available online: https://www.ftb.com.hr/archives/124-volume-33-issue-no-4/945-application-ofstarter-cultures-for-baked-goods (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Buksa, K. Effect of pentoses, hexoses, and hydrolyzed arabinoxylan on the most abundant sugar, organic acid, and alcohol contents during rye sourdough bread production. Cereal Chem. 2020, 97, 642–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corsetti, A.; Settanni, L. Lactobacilli in sourdough fermentation. Food Res. Int. 2007, 40, 539–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobbetti, M.; De Angelis, M.; Arnaut, P.; Tossut, P.; Corsetti, A.; Lavermicocca, P. Added pentosans in breadmaking: Fermentations of derived pentoses by sourdough lactic acid bacteria. Food Microbiol. 1999, 16, 409–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobbetti, M.; Lavermicocca, P.; Minervini, F.; De Angelis, M.; Corsetti, A. Arabinose fermentation by Lactobacillus plantarum in sourdough with added pentosans and αα-L-arabinofuranosidase: A tool to increase the production of acetic acid. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2000, 88, 317–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cauvain, S.P.; Young, L.S. Bakery Food Manufacture and Quality: Water Control and Effects, 2nd ed.; Wiley-Blackwell: Chichester, UK, 2008; ISBN 9781444301083. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Zhao, B.; Liu, C.-J.; Yang, E. Optimization of Biosynthesis Conditions for the Production of Exopolysaccharides by Lactobacillus plantarum SP8 and the Exopolysaccharides Antioxidant Activity Test. Indian J. Microbiol. 2020, 60, 334–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, C.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Wu, R.; Wu, J. Structural characterization and antioxidant potential of a novel exopolysaccharide produced by Bacillus velezensis SN-1 from spontaneously fermented Da-Jiang. Glycoconj. J. 2020, 37, 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Huang, L.; Li, K. Antioxidant activity changes of exopolysaccharides with different carbon sources from Lactobacillus plantarum LPC-1 and its metabolomic analysis. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 35, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmansy, E.A.; Elkady, E.M.; Asker, M.S.; Abdallah, N.A.; Khalil, B.E.; Amer, S.K. Improved production of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum RO30 exopolysaccharide (REPS) by optimization of process parameters through statistical experimental designs. BMC Microbiol. 2023, 23, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, M.Y.M.; Reehana, N.; Jayaraj, K.A.; Ahamed, A.A.P.; Dhanasekaran, D.; Thajuddin, N.; Alharbi, N.S.; Muralitharan, G. Statistical optimization of exopolysaccharide production by Lactobacillus plantarum NTMI05 and NTMI20. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2016, 93, 731–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Shao, C.; Liu, L.; Guo, X.; Xu, Y.; Lü, X. Optimization, partial characterization and antioxidant activity of an exopolysaccharide from Lactobacillus plantarum KX041. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 103, 1173–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Xiao, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhang, H.; Chen, W.; Lu, W. Lactic acid bacteria-derived exopolysaccharide: Formation, immunomodulatory ability, health effects, and structure-function relationship. Microbiol. Res. 2023, 274, 127432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afreen, A.; Ahmed, Z.; Khalid, N.; Ferheen, I.; Ahmed, I. Optimization and cholesterol-lowering activity of exopolysaccharide from Lactiplantibacillus paraplantarum NCCP 962. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2023, 107, 1189–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oleksy-Sobczak, M.; Klewicka, E.; Piekarska-Radzik, L. Exopolysaccharides production by Lactobacillus rhamnosus strains–Optimization of synthesis and extraction conditions. LWT 2020, 122, 109055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimada, P.S.; Abraham, A.G. Comparative study of different methodologies to determine the exopolysaccharide produced by kefir grains in milk and whey. Lait 2003, 83, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, J.; Guo, H.; Cheng, Q.; Abbas, Z.; Tong, Y.; Yang, T.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wei, X.; et al. Optimization of Exopolysaccharide Produced by Lactobacillus plantarum R301 and Its Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Activities. Foods 2023, 12, 2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Li, W.; Rui, X.; Chen, X.; Jiang, M.; Dong, M. Structural characterization and bioactivity of released exopolysaccharides from Lactobacillus plantarum 70810. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2014, 67, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Liu, Z.; Tao, X.; Wei, H. Characterization and sulfated modification of an exopolysaccharide from Lactobacillus plantarum ZDY2013 and its biological activities. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 153, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Li, Y.; Tian, J.; Zhou, J.; Xu, Q.; Feng, L.; Rui, X.; Fan, X.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, X.; et al. Influences of drying methods on the structural, physicochemical and antioxidant properties of exopolysaccharide from Lactobacillus helveticus MB2-1. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 157, 220–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuda, H.; Hara, K.; Miyamoto, T. Binding of mutagens to exopolysaccharide produced by Lactobacillus plantarum mutant strain 301102S. J. Dairy Sci. 2008, 91, 2960–2966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bata-Vidács, I.; Kosztik, J.; Mörtl, M.; Székács, A.; Kukolya, J. Aflatoxin B1 and Sterigmatocystin Binding Potential of Non-Lactobacillus LAB Strains. Toxins 2020, 12, 799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haskard, C.A.; El-Nezami, H.S.; Kankaanpää, P.E.; Salminen, S.; Ahokas, J.T. Surface Binding of Aflatoxin B1 by Lactic Acid Bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2001, 67, 3086–3091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafai, S.; Moreno, A.; Cimbalo, A.; Vila-Donat, P.; Manyes, L.; Meca, G. In Vitro Evaluation of Aflatoxin B1 Detoxification by Lactobacillus, Pediococcus, and Bacillus Strains. Toxins 2025, 17, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fouad, M.; El-Shenawy, M.; Hussein, A.; El-desouky, T. Impact of Lactic Acid Bacteria Cells on the Aflatoxin B1 in Wheat Flour During Manufacture Fino Bread. J. Chem. Health Risks 2023, 13, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanafari, A.; Soudi, H.; Miraboulfathi, M.; Osboo, R.K. An in vitro Investigation of Aflatoxin B1 Biological Control by Lactobacillus plantarum. Pak. J. Biol. Sci. 2007, 10, 2553–2556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emadi, A.; Eslami, M.; Yousefi, B.; Abdolshahi, A. In vitro strain specific reducing of aflatoxin B1 by probiotic bacteria: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Toxin Rev. 2022, 41, 995–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sezer, C.; Güven, A.; Bilge Oral, N.; Vatansever, L. Detoxification of aflatoxin B1 by bacteriocins and bacteriocinogenic lactic acid bacteria. Turk. J. Vet. Anim. Sci. 2013, 37, 594–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balsini, M.S.; Dovom, M.R.E.; Kadkhodaee, R.; Najafi, M.B.H.; Yavarmanesh, M. Effect of digestion and thermal processing on the stability of microbial cell-aflatoxin B1 complex. LWT 2021, 142, 110994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Møller, C.O.A.; Freire, L.; Rosim, R.E.; Margalho, L.P.; Balthazar, C.F.; Franco, L.T.; Sant’Ana, A.S.; Corassin, C.H.; Rattray, F.P.; Oliveira, C.A.F. Effect of Lactic Acid Bacteria Strains on the Growth and Aflatoxin Production Potential of Aspergillus parasiticus, and Their Ability to Bind Aflatoxin B1, Ochratoxin A, and Zearalenone in vitro. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 655386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.-H.; Jung, J.; Cho, W.; Lee, M. Lactic Acid Bacteria Probiotics Inhibit Interaction Between Aflatoxin B1 and HT29 Colorectal Cells by Directly Binding the Toxin. Food Suppl. Biomater. Health 2023, 3, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asurmendi, P.; Gerbaldo, G.; Pascual, L.; Barberis, L. Lactic acid bacteria with promising AFB1 binding properties as an alternative strategy to mitigate contamination on brewers’ grains. J. Environ. Sci. Health 2020, 55, 1002–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abedi, E.; Pourmohammadi, K.; Mousavifard, M.; Sayadi, M. Comparison between surface hydrophobicity of heated and thermosonicated cells to detoxify aflatoxin B1 by coculture Lactobacillus plantarum and Lactobacillus rhamnosus in sourdough: Modeling studies. LWT 2022, 154, 112616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damayanti, E.; Istiqomah, L.; Saragih, J.E.; Purwoko, T.; Sardjono. Characterization of Lactic Acid Bacteria as Poultry Probiotic Candidates with Aflatoxin B1 Binding Activities. Earth Environ. Sci. 2017, 101, 012030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Nezami, H.; Kankaanpaa, P.; Salminen, S.; Ahokas, J. Ability of dairy strains of lactic acid bacteria to bind a common food carcinogen, aflatoxin B1. Food Chem. Toxicol. 1998, 36, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, M.; Zhang, G.; Ding, S.; Jiang, Y.; Jiang, B.; Ren, D.; Chen, P. Lactobacillus plantarum T3 as an adsorbent of aflatoxin B1 effectively mitigates the toxic effects on mice. Food Biosci. 2022, 49, 101984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovo, F.; Corassin, C.H.; Rosim, R.E.; de Oliveira, C.A.F. Efficiency of Lactic Acid Bacteria Strains for Decontamination of Aflatoxin M1 in Phosphate Buffer Saline Solution and in Skimmed Milk. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2013, 6, 2230–2234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corassin, C.H.; Bovo, F.; Rosim, R.E.; Oliveira, C.A.F. Efficiency of Saccharomyces cerevisiae and lactic acid bacteria strains to bind aflatoxin M1 in UHT skim milk. Food Control 2013, 31, 80–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarlak, Z.; Rouhi, M.; Mohammadi, R.; Khaksar, R.; Mortazavian, A.M.; Sohrabvandi, S.; Garavand, F. Probiotic biological strategies to decontaminate aflatoxin M1 in a traditional Iranian fermented milk drink (Doogh). Food Control 2017, 71, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haskard, C.; Binnion, C.; Ahokas, J. Factors affecting the sequestration of aflatoxin by Lactobacillus rhamnosus strain GG. Chem.-Biol. Interact. 2000, 128, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, A.; Levin, R.E.; Riaz, M.; Akhtar, S.; Gong, Y.Y.; de Oliveira, C.A.F. Effect of different microbial concentrations on binding of aflatoxin M1 and stability testing. Food Control 2017, 73, 492–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosztik, J.; Mörti, M.; Székács, A.; Kukolya, J.; Bata-Vidács, I. Aflatoxin B1 and Sterigmatocystin Binding Potential of Lactobacilli. Toxins 2020, 12, 756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Liu, X.; Yuan, L.; Li, J. Complicated interactions between bio-adsorbents and mycotoxins during mycotoxin adsorption: Current research and future prospects. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 96, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Genotype | Isolate |

|---|---|

| G1 | L. plantarum A38 |

| L. plantarum A57 | |

| G5 | L. plantarum A45 |

| L. plantarum A52 | |

| G6 | L. plantarum A44 |

| L. plantarum A51 | |

| G9 | L. plantarum A26 |

| L. plantarum A37 | |

| G12 | L. plantarum A10 |

| L. plantarum A71 |

| Genotype | Strain | Antibiotic Class | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β-Lactam | Amphenicol | Lincos-amide | Macrolide | Aminoglycoside | Tetracycline | Glycopeptide | ||||

| AMP | CHL | CLI | ERY | GEN | KAN | STR | TET | VAN | ||

| G1 | A38 | 0.50 ± 0.00 | 2.00 ± 0.00 | 0.02 ± 0.00 | 0.12 ± 0.07 | 1.06 ± 1.68 | 28.00 ± 5.66 | 10.00 ± 8.49 | 2.00 ± 0.00 | >32.00 |

| A57 | 0.67 ± 0.29 | 1.67 ± 0.58 | 0.02 ± 0.00 | 0.14 ± 0.10 | 3.00 ± 0.00 | >32.00 | 16.00 ± 0.00 | 10.00 ± 2.83 | >32.00 | |

| G5 | A45 | 0.07 ± 0.02 | 1.83 ± 0.29 | 1.75 ± 0.35 | 0.35 ± 0.00 | 1.29 ± 1.48 | >32.00 | 24.00 ± 0.00 | 6.00 ± 2.00 | >32.00 |

| A52 | 0.11 ± 0.07 | 2.17 ± 0.76 | 0.02 ± 0.00 | 0.04 ± 0.02 | 0.75 ± 0.25 | 7.00 ± 1.41 | 14.00 ± 2.83 | 1.50 ± 0.50 | >32.00 | |

| G6 | A44 | 0.27 ± 0.10 | 1.83 ± 0.29 | 0.02 ± 0.00 | 0.10 ± 0.02 | 1.83 ± 0.29 | 29.33 ± 4.62 | 21.33 ± 4.62 | 2.50 ± 0.87 | >32.00 |

| A51 | 0.32 ± 0.11 | 0.92 ± 0.14 | 0.02 ± 0.00 | 0.19 ± 0.06 | 2.50 ± 1.32 | 32.00 ± 0.00 | 13.33 ± 4.62 | 1.08 ± 0.38 | >32.00 | |

| G9 | A26 | 0.13 ± 0.06 | 1.17 ± 0.76 | 0.02 ± 0.00 | 0.10 ± 0.02 | 0.92 ± 0.14 | 32.00 ± 0.00 | 12.00 ± 4.00 | 2.33 ± 1.53 | >32.00 |

| A37 | 0.27 ± 0.20 | 1.33 ± 0.58 | 0.02 ± 0.00 | 1.36 ± 1.10 | 0.83 ± 0.14 | 10.00 ± 2.83 | 11.33 ± 5.03 | 1.58 ± 0.72 | >32.00 | |

| G12 | A10 | 0.42 ± 0.14 | 2.50 ± 1.32 | 0.02 ± 0.00 | 0.17 ± 0.04 | 1.83 ± 0.29 | 28.00 ± 5.66 | 20.00 ± 5.66 | 3.67 ± 0.58 | >32.00 |

| A71 | 0.34 ± 0.28 | 3.00 ± 0.00 | 0.02 ± 0.00 | 0.13 ± 0.00 | 0.83 ± 0.14 | 32.00 ± 0.00 | 24.00 ± 0.00 | 2.67 ± 1.15 | >32.00 | |

| Cut-off values 1 | ≤2 | ≤8 | ≤4 | ≤1 | ≤16 | ≤64 | n.r. | ≤32 | n.r. | |

| Enzyme | Genotypes and Strains | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G1 | G5 | G6 | G9 | G12 | ||||||

| A38 | A57 | A45 | A52 | A44 | A51 | A26 | A37 | A10 | A71 | |

| Alkaline phosphatase | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Esterase | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| Esterase lipase | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| Lipase | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Leucine arylamidase | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Valine arylamidase | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 5 |

| Cystine arylamidase | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 |

| Trypsin | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| α-chymotrypsin | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Acid phosphatase | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 |

| Naphthol-AS-BI phosphohydrolase | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| α-galactosidase | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| β-galactosidase | 5 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 4 |

| β-glucuronidase | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| α-glucosidase | 5 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| β-glucosidase | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| N-Acetyl-β-glucosaminidase | 3 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 5 |

| α-mannosidase | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| α-fucosidase | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Carbon Source | Genotypes and Strains | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G1 | G5 | G6 | G9 | G12 | ||||||

| A38 | A57 | A45 | A52 | A44 | A51 | A26 | A37 | A10 | A71 | |

| L-Arabinose | + | + | - | - | - | - | + | + | + | - |

| D-Ribose | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| D-Xylose | + | - | - | - | - | - | + | + | - | - |

| D-Galactose | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| D-Glucose | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| D-Fructose | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| D-Mannose | + | + | + | + | + | + | - | + | + | + |

| D-Mannitol | + | + | + | + | + | + | - | + | + | + |

| D-Sorbitol | + | + | + | + | + | + | - | + | + | + |

| Methyl-α-D-mannopyranoside | + | + | + | + | + | + | - | + | + | - |

| N-Acetylglucosamine | + | + | + | - | + | + | - | + | + | + |

| Amygdalin | + | + | + | + | + | + | - | + | + | + |

| Arbutin | + | + | + | + | + | + | - | + | + | + |

| Esculin | + | + | - | + | - | + | + | + | + | + |

| Salicin | + | + | + | + | + | + | - | + | + | + |

| D-Cellobiose | + | + | + | + | + | + | - | + | + | + |

| D-Maltose | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| D-Lactose | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| D-Melibiose | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| D-Saccharose | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| D-Trehalose | + | + | + | + | + | + | - | + | + | + |

| Inulin | + | - | + | - | + | - | - | + | + | - |

| D-Melezitose | + | + | + | + | + | - | - | + | + | + |

| D-Raffinose | + | + | + | + | + | - | + | + | + | + |

| Starch | - | - | - | - | - | + | - | - | - | - |

| Gentiobiose | + | + | + | + | + | - | - | + | + | + |

| D-Turanose | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | + | + |

| D-Lyxose | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | + | - |

| D-Tagatose | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | + | - |

| D-Fucose | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | + | - |

| L-Fucose | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | + | - |

| D-Arbitol | - | - | + | - | + | - | - | - | + | - |

| L-Arbitol | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | + | - |

| Potassium gluconate | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | - | + | + |

| Potassium 5-ketogluconate | - | - | - | - | - | - | + | - | - | - |

| Parameter | Strains and Genotypes | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G1 | G5 | G6 | G9 | G12 | ||||||

| A38 | A57 | A45 | A52 | A44 | A51 | A26 | A37 | A10 | A71 | |

| Lactic acid | 12.7 ± 3.1 ab | 14.0 ± 1.6 ab | 13.3 ± 2.8 ab | 21.6 ± 4.1 ab | 13.3 ± 1.8 ab | 11.4 ± 0.9 a | 12.7 ± 3.2 ab | 15.4 ± 0.4 b | 15.1 ± 4.8 ab | 16.3 ± 2.6 ab |

| Acetic acid | 2.8 ± 0.3 a | 2.0 ± 0.6 ab | 1.7 ± 0.2 b | 1.9 ± 0.8 ab | 2.2 ± 0.7 ab | 2.2 ± 0.7 ab | 1.8 ± 0.2 b | 2.3 ± 0.2 ab | 2.3 ± 0.9 ab | 2.5 ± 0.5 ab |

| Total acids | 15.5 ± 3.1 | 16.0 ± 1.7 | 15.0 ± 2.8 | 23.5 ± 4.2 | 15.5 ± 1.9 | 13.6 ± 1.1 | 14.5 ± 3.2 | 17.7 ± 0.5 | 17.4 ± 4.9 | 18.8 ± 2.6 |

| Ethanol | 5.2 ± 1.2 b | 4.1 ± 0.8 b | 4.2 ± 4.2 a | 11.8 ± 1.5 a | 3.9 ± 0.5 c | 3.7 ± 1.5 b | 6.7 ± 2.2 a | 5.7 ± 1.2 a | 4.6 ± 1.9 a | 13.8 ± 2.7 a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lutter, L.; Sahharov, P.; Othman, S.B.; Luik, L.; Pikkel, N.; Schneider, A.; Andreson, H. Metabolic and Safety Characterization of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum Strains Isolated from Traditional Rye Sourdough. Fermentation 2025, 11, 677. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation11120677

Lutter L, Sahharov P, Othman SB, Luik L, Pikkel N, Schneider A, Andreson H. Metabolic and Safety Characterization of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum Strains Isolated from Traditional Rye Sourdough. Fermentation. 2025; 11(12):677. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation11120677

Chicago/Turabian StyleLutter, Liis, Pavel Sahharov, Sana Ben Othman, Lisbeth Luik, Naatan Pikkel, Anna Schneider, and Helena Andreson. 2025. "Metabolic and Safety Characterization of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum Strains Isolated from Traditional Rye Sourdough" Fermentation 11, no. 12: 677. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation11120677

APA StyleLutter, L., Sahharov, P., Othman, S. B., Luik, L., Pikkel, N., Schneider, A., & Andreson, H. (2025). Metabolic and Safety Characterization of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum Strains Isolated from Traditional Rye Sourdough. Fermentation, 11(12), 677. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation11120677