2G Ethanol Production from a Cellulose Derivative

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Determination of the Substitution Degree (DS) of the Cellulose Acetate

2.2.2. FT-IR Spectroscopy

2.2.3. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD)/Crystallinity

2.2.4. Hydrolysis Reactions of the Material and Quantification of Glucose

2.2.5. HPLC Analysis

2.2.6. Fermentation

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Degree of Substitution of Cellulose Acetate

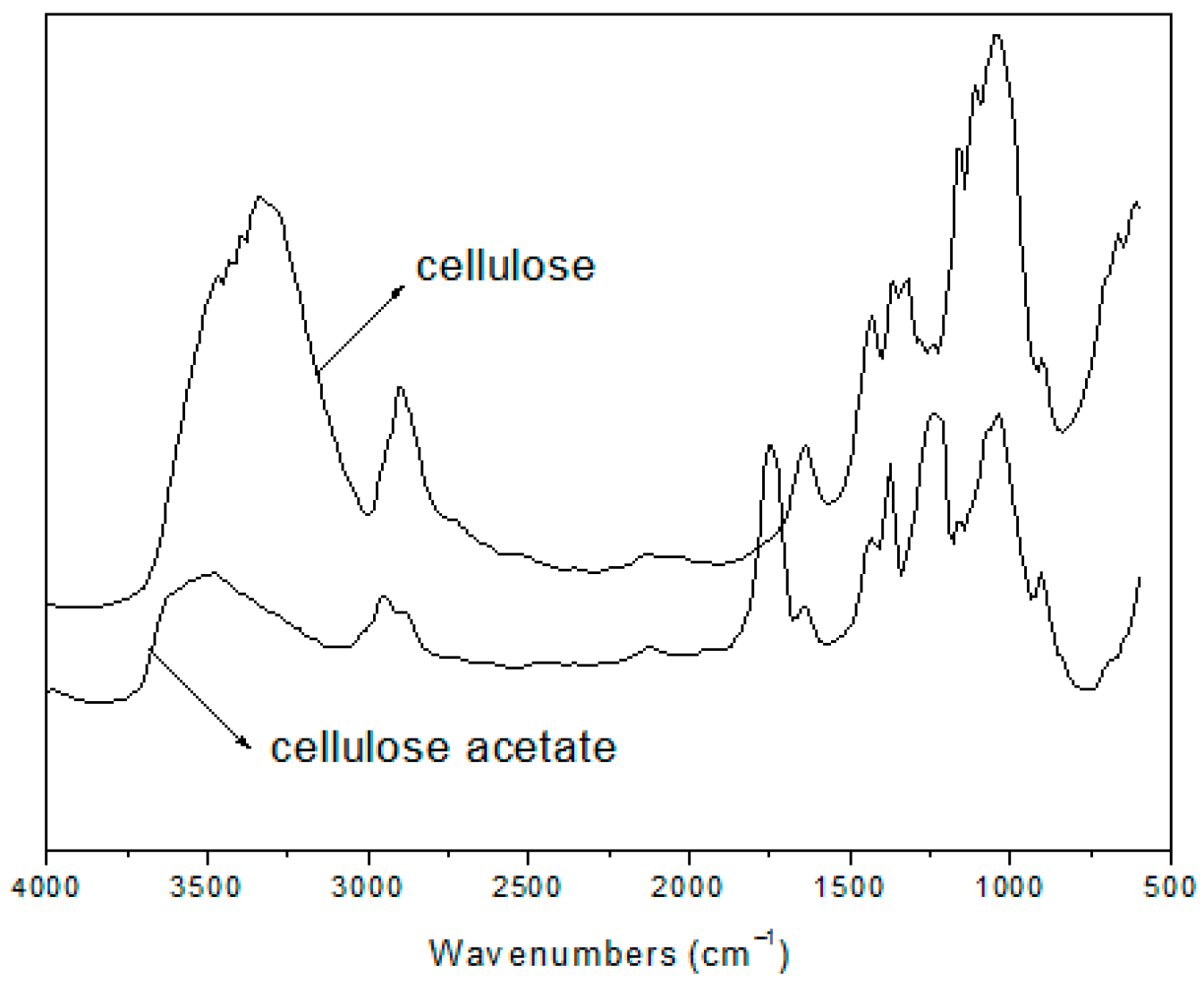

3.2. FT-IR Spectra

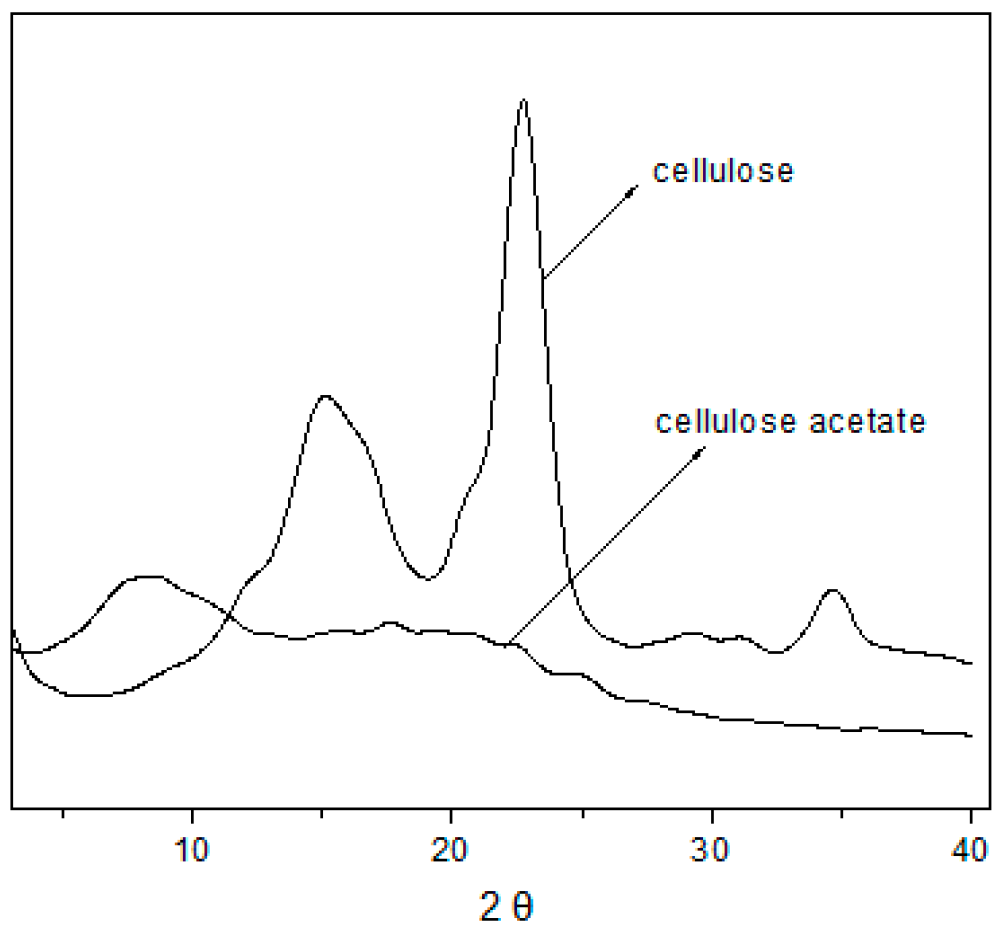

3.3. Analysis of the X-Ray Diffraction (XRD)

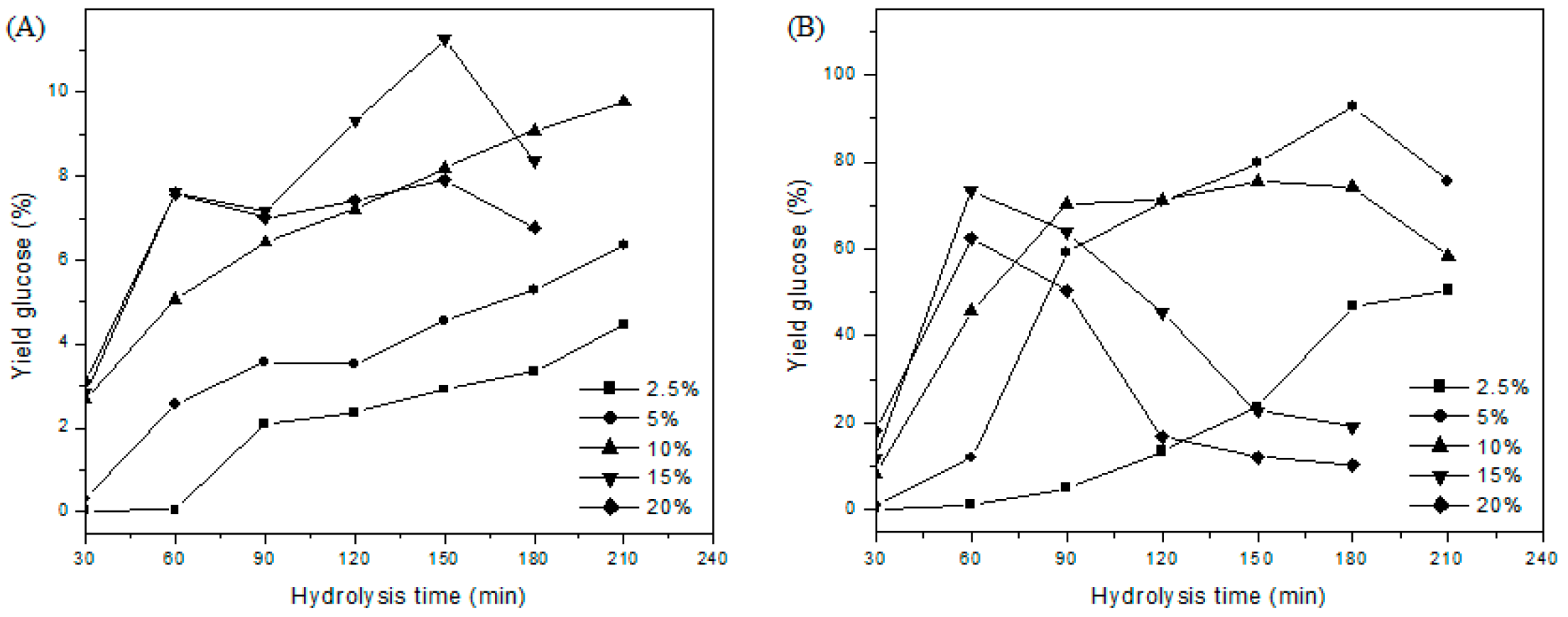

3.4. Hydrolysis of Materials

3.5. Composition of the Hydrolyzate

3.6. Fermentation-Ethanol 2G Production

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 2G | Second generation |

| FTIR | Fourier transform infrared |

| MCC | microcrystalline cellulose |

| S.A. | Standard analytical |

| DS | substitution degree |

| %AG | percentage of acetyl groups |

| Vb | volume of base |

| Vbt | base volume spends in the titration |

| Mb | molarity of the acid |

| MM | molar mass acetyl groups |

| mac | mass of cellulose acetate |

| KOH | potassium hydroxide |

| KBr | Potassium bromide |

| HMF | hydroxymethylfurfural |

| H2SO4 | sulfuric acid |

| CI | Crystal index |

| hcr | crystalline scatter |

| GA | acetyl groups |

| ham | amorphous height |

| UV | Ultraviolet |

| UV-vis | Visible Ultraviolet |

| HPLC | High-performance liquid chromatography |

| pH | hydrogenionic potential |

| cm | Centimetre |

| mL | Millilitre |

| °C | Degree Celsius |

| min | Minutes |

| nm | Nanometre |

| mol | mol |

| w/w | Weight by weight |

| v/v | volume by volume |

| CAT-1 | Saccharomyces cerevisiae |

| g | Grams |

| rpm | rotations per minute |

| L | Liter |

| mg | Milligram |

References

- Reddy, N.; Yang, Y. Biocomposites using lignocellulosic agricultural residues as reinforcement. In Innovative Biofibers from Renewable Resources; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 391–417. [Google Scholar]

- Rashid, B.; Leman, Z.; Jawaid, M.; Ghazali, M.J.; Ishak, M.R. Physicochemical and thermal properties of lignocellulosic fiber from sugar palm fibers: Effect of treatment. Cellulose 2016, 23, 2905–2916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, L.G.S.; Rodrigues, T.H.S.; Rates, E.R.D.; Alencar, L.M.R.; Rosa, M.F.; Rocha, M.V.P. Production of cellulose nanoparticles from cashew apple bagasse by sequential enzymatic hydrolysis with an ultrasonic process and its application in biofilm packaging. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 50671–50684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Linc, L.; Wu, Z.; Zhou, S.; Liu, S. Chemocatalytic hydrolysis of cellulose into glucose over solid acid catalysts. Appl. Catal. B Environ. Energy 2015, 174–175, 225–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brum, S.S. Sulfated Zirconia Catalysts and Activated Carbon/Sulfated Zirconia Composites for Biodiesel and Ethanol Production. Ph.D. Thesis, University Federal of Lavras (UFLA), Lavras, Brazil, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Evangelista, I.; Arruda, A.; Menezes, L.; Fischer, J.; Guidini, C.Z. Physicochemical characterization of agro-industrial residues for second-generation ethanol production. Res. Soc. Dev. 2021, 10, e33110817151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, A.I.; Mehta, N.; Elgarahy, A.M.; Al-Hinai, A.; Al-Muhtaseb, A.A.H.; Rooney, D.W. Conversion of biomass to biofuels and life cycle assessment: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2021, 19, 4075–4118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Verma, J.P. Sustainable bio-ethanol production from agro-residues: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 41, 550–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortez, L.A.B.; Lora, E.E.S.; Gómez, E.O. Biomass for Energy, 1st ed.; Unicamp: Campinas, Brazil, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Chimentao, R.J.; Lorente, E.; Gispert-Guirado, F.; Medina, F.; Lopez, F. Hydrolysis of dilute acid-pretreated cellulose under mild hydrothermal conditions. Carbohydr. Polym. 2014, 111, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Kao, M.-R.; Li, J.; Sun, P.; Meng, Q.; Vyas, A.; Liang, P.-H.; Wang, Y.-S.; Hsieh, Y.S.Y. Characterization of cellulose-derived oligosaccharides and their application in intestinal barrier modulation. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 9941–9947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabelo, S.C. Evaluation and Optimization of Pretreatment and Enzymatic Hydrolysis of Sugarcane Bagasse for Second Generation Ethanol Production. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Campinas, Campinas, Brazil, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Jönsson, L.J.; Martín, C. Pretreatment of lignocellulose: Formation of inhibitory by-products and strategies for minimizing their effects. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 199, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, J.; Ming, H.; Hu, H.; Dou, X.; Xiao, Y.; Cheng, L.; Hu, Z. Investigation of Cotton Stalk-Derived Hydrothermal Bio-Oil: Effects of Mineral Acid/Base and Oxide Additions. Energies 2024, 17, 4854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, S.; Wang, S.; Han, Y.; Cai, B.; Li, H. Influence of reaction conditions on heterogeneous hydrolysis of cellulose over phenolic residue-derived solid acid. Fuel 2014, 134, 573–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medicines, T.M.; Ampa, R.; Nguimbi, E.; Bissombolo, P.M.; Ngo-Itsouhou; Mabika, F.A.S.; Ngoulou, T.B.; Nzaou, S.A.E. Optimization of cellulase production conditions in bacteria isolated from soils in Brazzaville. J. Biosci. Med. 2022, 10, 14–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parajuli, P.; Acharya, S.; Hu, Y.; Abidi, N. Cellulose-based monoliths with enhanced surface area and porosity. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2020, 137, 48975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liyanage, S.; Acharya, S.; Parajuli, P.; Shamshina, J.L.; Abidi, N. Production and Surface Modification of Cellulose Bioproducts. Polymers 2021, 13, 3433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puelo, A.C.; Paul, D.R.; Kelley, S.S. The effect of acetylation on gas sorption and transport behavior in cellulose acetate. J. Membr. Sci. 1989, 47, 301–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lengowski, E.C.; Muniz, G.I.B.; Nisgoski, S.; Magalhães, W.L.E. Evaluation of methods for obtaining cellulose with different degrees of crystallinity. Sci. For. 2013, 41, 185–194. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, B.; Duan, L.; Peng, G.; Li, X.; Xu, A. Efficient production of glucose by microwave-assisted acid hydrolysis of cellulose hydrogel. Bioresour. Technol. 2015, 192, 253–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desmet, T.; Morent, R.; De Geyter, N.; Leys, C.; Schacht, E.; Dubruel, P. Nonthermal plasma technology as a versatile strategy for polymeric biomaterials surface modification: A review. Biomacromolecules 2009, 10, 2351–2378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martín, C.; Alriksson, B.; Sjöde, A.; Nilvebrant, N.; Jönsson, L.J. Dilute sulfuric acid pretreatment of agricultural and agro-industrial residues for ethanol production. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2007, 137, 339–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ask, M.; Bettiga, M.; Duraiswamy, V.; Olsson, L. Pulsed addition of HMF and furfural to batch-grown xylose-utilizing Saccharomyces cerevisiae results in different physiological responses in glucose and xylose consumption phase. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2013, 6, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, S.; Clark, W.; McCaffery, J.M.; Cai, Z.; Lanctot, A.; Slininger, P.; Liu, Z.L.; Gorsich, S.W. Furfural induces reactive oxygen species accumulation and cellular damage in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2010, 3, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, J.R.M.; Modig, T.; Petersson, A.; Hähn-Hägerdal, B.; Lidén, G.; Gorwa-Grauslund, M.F. Increased tolerance and conversion of inhibitors in lignocellulosic hydrolysates by Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2007, 82, 340–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, Y.; Hao, X.; Wang, L.; Jiang, X.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, C.; Meng, Y.; Xia, H.; Chen, Z. Superhydrophobic and flexible silver nanowire-coated cellulose filter papers with sputter-deposited nickel nanoparticles for ultrahigh electromagnetic interference shielding. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 14623–14633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, W.C.; Silva, D.B.; Pereira, N., Jr. Ethanol production from castor bean cake (Ricinus communis L.) and evaluation of the lethality of the cake for mice. Quim. Nova 2008, 31, 1104–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, J.B. Process of Solubilization, Hydrolysis and Degradation of Cellulose and Derivatives in the Presence of Sn (IV)-Based Metal Catalysts. Master’s Thesis, University Federal of Maceio, Maceió, Brazil, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Alriksson, B.; Sjöde, A.; Nilvebrant, N.O.; Jönsson, L.J. Optimal conditions for alkaline detoxification of dilute-acid lignocellulose hydrolysates. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2006, 129, 599–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Worku, N. Optimization of hydrolysis in ethanol production from sugarcane bagasse. Res. Sq. 2022; Preprint. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y.; Malten, M.; Torry-Smith, M.; McMillan, J.D.; Stickel, J.J. Calculating sugar yields in high solids hydrolysis of biomass. Bioresour. Technol. 2011, 102, 2897–2903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sample * | Glucose (g·L−1) | HMF (mg·L−1) | Furfural (mg·L−1) | Acetate (g·L−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A5-60 | 0.92 | 0 | 1 | 3.24 |

| A10-60 | 3.99 | 0 | 49 | 4.98 |

| A15-60 | 6.90 | 7 | 53 | 5.00 |

| A20-60 | 5.93 | 17 | 45 | 4.99 |

| A5-90 | 4.57 | 8 | 17 | 4.40 |

| A10-90 | 6.71 | 2 | 55 | 4.95 |

| A15-90 | 6.18 | 14 | 48 | 4.81 |

| A20-90 | 5.76 | 23 | 41 | 5.03 |

| A2.5-120 | 0.78 | 29 | 0 | 2.87 |

| A5-120 | 6.61 | 0 | 37 | 4.92 |

| A10-120 | 6.98 | 5 | 57 | 5.19 |

| A2.5-150 | 1.64 | 28 | 4 | 3.36 |

| A5-150 | 6.76 | 0 | 47 | 4.82 |

| A10-150 | 6.81 | 6 | 56 | 5.14 |

| A2.5-180 | 3.09 | 27 | 9 | 4.09 |

| A5-180 | 8.17 | 1 | 53 | 5.52 |

| A10-180 | 6.42 | 0 | 54 | 5.01 |

| A2.5-210 | 3.94 | 0 | 21 | 2.81 |

| A5-210 | 6.86 | 0 | 32 | 4.81 |

| A10-210 | 5.18 | 0 | 47 | 4.66 |

| Time (h) | Glucose (g·L−1) | Ethanol (g·L−1) | HMF (g·L−1) | Furfural (g·L−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 17.95 | 0.00 | 0.023 | 0.000 |

| 15 | 12.88 | 2.84 | 0.015 | 0.000 |

| 17 | 9.10 | 4.34 | 0.003 | 0.000 |

| 19 | 4.30 | 6.71 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| 21 | 0.85 | 8.29 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| 23 | 0.00 | 8.66 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| 25 | 0.00 | 8.87 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Grossi, E.C.; Andrade, R.D.A.; Suarez, P.A.Z.; Brum, S.S. 2G Ethanol Production from a Cellulose Derivative. Fermentation 2025, 11, 676. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation11120676

Grossi EC, Andrade RDA, Suarez PAZ, Brum SS. 2G Ethanol Production from a Cellulose Derivative. Fermentation. 2025; 11(12):676. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation11120676

Chicago/Turabian StyleGrossi, Elton C., Romulo D. A. Andrade, Paulo A. Z. Suarez, and Sarah S. Brum. 2025. "2G Ethanol Production from a Cellulose Derivative" Fermentation 11, no. 12: 676. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation11120676

APA StyleGrossi, E. C., Andrade, R. D. A., Suarez, P. A. Z., & Brum, S. S. (2025). 2G Ethanol Production from a Cellulose Derivative. Fermentation, 11(12), 676. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation11120676