Valorization of Artichoke Wastes via Ozonation Pretreatment and Enzyme Fibrolytic Supplementation: Effect on Nutritional Composition, Ruminal Fermentation and Degradability

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Preparation

2.2. Chemical Composition

2.3. Ruminal Fermentation

2.4. Statical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Chemical Composition

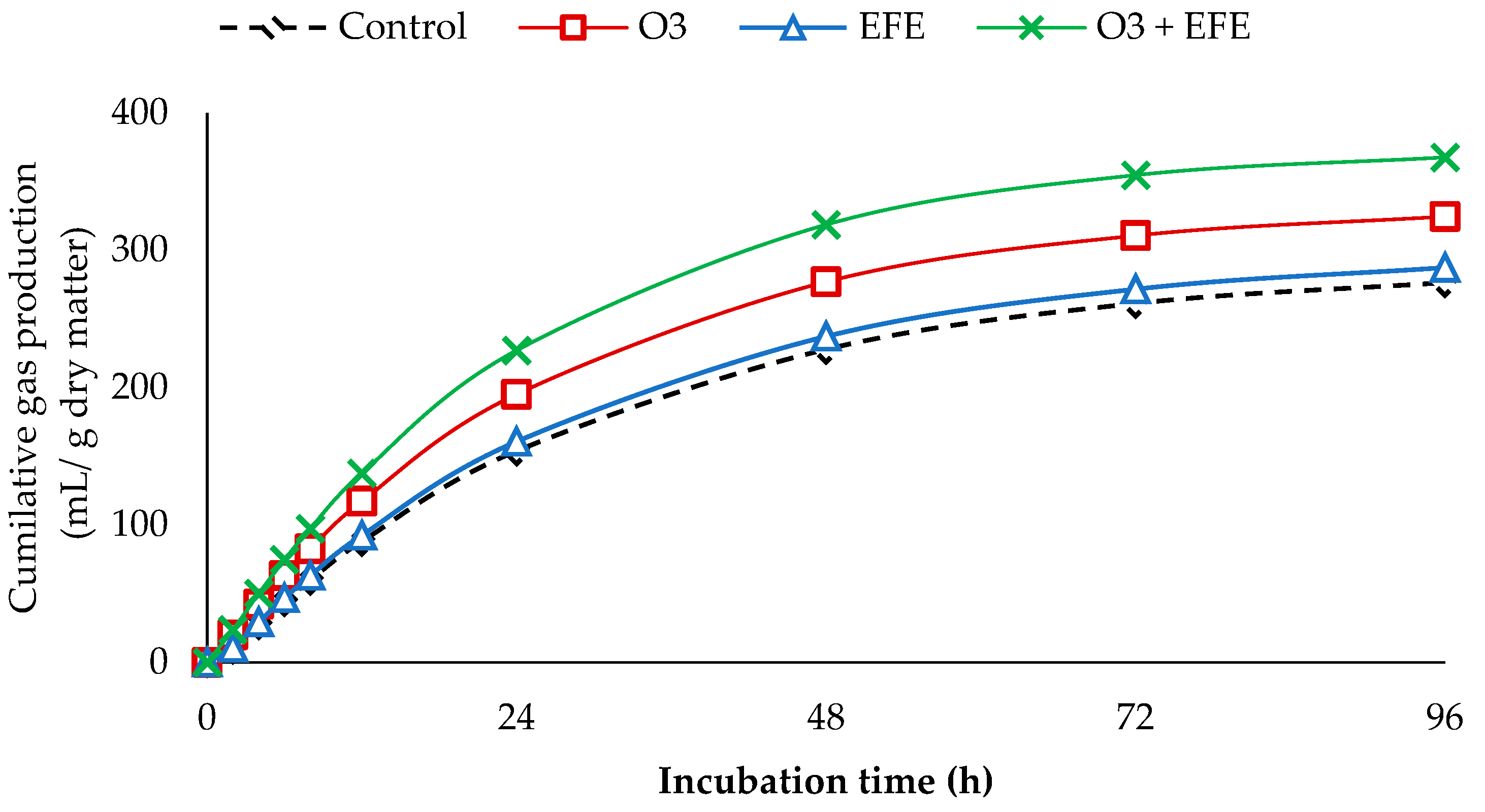

3.2. In Vitro Gas Production

3.3. Ruminal Fermentation Parameters and Degradability

3.4. Ruminal Microbiota Population and Enzyme Activity

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADL | Acid detergent lignin |

| C | Fractional rate of gas production |

| CP | Crude protein |

| DMD | Dry matter degradability |

| EE | Ether extract |

| EFE | Exogenous fibrolytic enzyme |

| GP | Gas pressure |

| Gv | Gas volume |

| Lag | Time at which gas production starts |

| ME | Metabolizable energy |

| NDF | Neutral detergent fiber |

| NDFD | Neutral detergent fiber degradability |

| NFC | Non-fiber carbohydrate |

| Patm | Atmospheric pressure |

| PGP | Potential gas production |

| SEM | Standard error of means |

| CT | Condensed tannins |

| TP | Total polyphenols |

| TT | Total tannins |

| Vf | Volume of the bottle |

| VFA | Volatile fatty acid |

| Vi | Volume of inoculum added at the start of incubation |

| O3 | Ozone |

References

- Meneses, M.; Megías, M.D.; Madrid, J.; Martínez-Teruel, A.; Hernández, F.; Oliva, J. Evaluation of the Phytosanitary, Fermentative and Nutritive Characteristics of the Silage Made from Crude Artichoke (Cynara scolymus L.) by-Product Feeding for Ruminants. Small Rumin. Res. 2007, 70, 292–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monllor, P.; Romero, G.; Sendra, E.; Atzori, A.S.; Díaz, J.R. Short-Term Effect of the Inclusion of Silage Artichoke By-Products in Diets of Dairy Goats on Milk Quality. Animals 2020, 10, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muelas, R.; Monllor, P.; Romero, G.; Sayas-Barberá, E.; Navarro, C.; Díaz, J.; Sendra, E. Milk Technological Properties as Affected by Including Artichoke By-Products Silages in the Diet of Dairy Goats. Foods 2017, 6, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Megías, M.D.; Hernández, F.; Madrid, J.; Martínez-Teruel, A. Feeding Value, in Vitro Digestibility and in Vitro Gas Production of Different By-products for Ruminant Nutrition. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2002, 82, 567–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Rodríguez, J.; Ranilla, M.J.; France, J.; Alaiz-Moretón, H.; Carro, M.D.; López, S. Chemical Composition, In Vitro Digestibility and Rumen Fermentation Kinetics of Agro-Industrial By-Products. Animals 2019, 9, 861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsico, G.; Ragni, M.; Vicenti, A.; Caputi Jambrenghi, A.; Tateo, A.; Giannico, F.; Vonghia, G. The quality of meat from lambs and kids reared on feeds based on artichoke (Cynara scolymus L.) BRACTS. Acta Hortic. 2005, 681, 489–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salman, F.M.M.; El-Nomeary, Y.A.A.; Abedo, A.A.; Abd El-Rahman, H.H.; Mohamed, M.I.; Ahmed, S.M. Utilization of Artichoke (Cynara scolymus) By-Products in Sheep Feeding. Am. Eurasian J. Agric. Environ. Sci. 2014, 14, 624–630. [Google Scholar]

- Pizarro, D.M.; Trujillo, G.M.; Gómez, C.A. Effect of Feeding Artichoke Bracts Silage on Production of Confined Dairy Cattle. Livest. Res. Rural Dev. 2019, 31, 34. [Google Scholar]

- Monllor, P.; Muelas, R.; Roca, A.; Atzori, A.; Díaz, J.; Sendra, E.; Romero, G. Long-Term Feeding of Dairy Goats with Broccoli By-Product and Artichoke Plant Silages: Milk Yield, Quality and Composition. Animals 2020, 10, 1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monllor, P.; Muelas, R.; Roca, A.; Bueso-Ródenas, J.; Atzori, A.S.; Sendra, E.; Romero, G.; Díaz, J.R. Effect of the Short-Term Incorporation of Different Proportions of Ensiled Artichoke By-Product on Milk Parameters and Health Status of Dairy Goats. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monllor, P.; Zemzmi, J.; Muelas, R.; Roca, A.; Sendra, E.; Romero, G.; Díaz, J.R. Long-Term Feeding of Dairy Goats with 40% Artichoke by-Product Silage Preserves Milk Yield, Nutritional Composition and Animal Health Status. Animals 2023, 13, 3585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forte, L.; Natrella, G.; Seccia, A.; De Palo, P.; Tomasevic, I.; De Angelis, D.; Ceci, E.; Hopkins, D.L.; Maggiolino, A. Artichoke Bracts Silage in the Finishing Diet of Beef Steers: Meat Quality during Dry Aging. Meat Sci. 2025, 228, 109900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sewalt, V.; Shanahan, D.; Gregg, L.; La Marta, J.; Carrillo, R. The Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS) Process for Industrial Microbial Enzymes. Ind. Biotechnol. 2016, 12, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Chatterjee, A.; Dutta, T.K.; Reena, Y.; Mohammad, A.; Bhakat, C.; Rai, S.; Mandal, D.K.; Karunakaran, M. Effect of Exogenous Fibrolytic Enzymes Supplementation on Voluntary Intake, Availability of Nutrients and Growth Performance in Black Bengal Kids (Capra hircus). Small Rumin. Res. 2023, 220, 106912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bureenok, S.; Pitiwittayakul, N.; Saenmahayak, B.; Saithi, S.; Yuangklang, C.; Cai, Y.; Schonewille, J.T. Effects of Fibrolytic Enzyme Supplementation on Feed Intake, Digestibility and Rumen Fermentation Characteristics in Goats Fed with Leucaena Silage. Small Rumin. Res. 2024, 231, 107200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zhao, S.; Lin, B. Effect of Commercial Fibrolytic Enzymes Application to Normal- and Slightly Lower Energy Diets on Lactational Performance, Digestibility and Plasma Nutrients in High-Producing Dairy Cows. Front. Vet. Sci. 2024, 11, 1302034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, I.M.; Mantovani, H.C.; Vedovatto, M.; Cardoso, A.S.; Rodrigues, A.A.; Homem, B.G.C.; De Abreu, M.J.I.; Rodrigues, A.N.; Cursino Batista, L.H.; De Oliveira, J.S.; et al. Impact of Dietary Exogenous Feed Enzymes on Performance, Nutrient Digestibility, and Ruminal Fermentation Parameters in Beef Cattle: A Meta-Analysis. animal 2025, 19, 101481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, I.M.; Mantovani, H.C.; Viquez-Umana, F.; Granja-Salcedo, Y.T.; E Silva, L.F.C.; Koontz, A.; Holder, V.; Pettigrew, J.E.; Rodrigues, A.A.; Rodrigues, A.N.; et al. Feeding Amylolytic and Fibrolytic Exogenous Enzymes in Feedlot Diets: Effects on Ruminal Parameters, Nitrogen Balance and Microbial Diversity of Nellore Cattle. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2025, 16, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Li, W.; Zhao, C.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, L.; Li, X.; Yao, J.; Pellikaan, W.F.; Cao, Y. Effects of Fibrolytic and Amylolytic Compound Enzyme Preparation on Rumen Fermentation, Serum Parameters and Production Performance in Primiparous Early-Lactation Dairy Cows. J. Dairy Res. 2024, 91, 167–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakita, G.Z.; Lima, P.D.M.T.; Abdalla Filho, A.L.; Bompadre, T.F.V.; Ovani, V.S.; Chaves, C.D.M.E.S.; Bizzuti, B.E.; Costa, W.D.S.D.; Paim, T.D.P.; Campioni, T.S.; et al. Treating Tropical Grass with Fibrolytic Enzymes from the Fungus Trichoderma Reesei: Effects on Animal Performance, Digestibility and Enteric Methane Emissions of Growing Lambs. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2022, 286, 115253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lago, R.V.P.; Da Cruz, J.M.; Wolschick, G.J.; Signor, M.H.; Breancini, M.; Klein, B.; Silva, L.E.L.; Wagner, R.; Hamerski, M.E.P.; Kozloski, G.V.; et al. Addition of Exogenous Fibrolytic Enzymes to the Feed of Confined Steers Modulates Fat Profile in Meat. Ruminants 2025, 5, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abid, K.; Jabri, J.; Beckers, Y.; Yaich, H.; Malek, A.; Rekhis, J.; Kamoun, M. Effects of Exogenous Fibrolytic Enzymes on the Ruminal Fermentation of Agro-Industrial by-Products. S. Afr. J. Anim. Sci. 2019, 49, 612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abid, K.; Jabri, J.; Yaich, H.; Malek, A.; Rekhis, J.; Kamoun, M. In Vitro Study on the Effects of Exogenic Fibrolytic Enzymes Produced from Trichoderma longibrachiatum; on Ruminal Degradation of Olive Mill Waste. Arch. Anim. Breed. 2022, 65, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abid, K.; Jabri, J.; Yaich, H.; Malek, A.; Rekhis, J.; Kamoun, M. Conversion of Posidonia oceanica Wastes into Alternative Feed for Ruminants by Treatment with Microwaves and Exogenous Fibrolytic Enzymes Produced by Fermentation of Trichoderma Longibrachiatum. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 2023, 13, 16529–16536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abid, K. Effects of Gamma Irradiation Pretreatment and Exogenous Fibrolytic Enzyme Supplementation on the Ruminal Fermentation and Nutritional Value of Typha latifolia. Fermentation 2025, 11, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabri, J.; Ammar, H.; Abid, K.; Beckers, Y.; Yaich, H.; Malek, A.; Rekhis, J.; Morsy, A.S.; Soltan, Y.A.; Soufan, W.; et al. Effect of Exogenous Fibrolytic Enzymes Supplementation or Functional Feed Additives on In Vitro Ruminal Fermentation of Chemically Pre-Treated Sunflower Heads. Agriculture 2022, 12, 696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kojima, Y.; Yoon, S.-L. Improved Enzymatic Hydrolysis of Waste Paper by Ozone Pretreatment. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2008, 10, 134–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadnezhad, B.; Pirmohammadi, R.; Khalilvandi Behroozyar, H. Effect of Processing with Ozone on in Vitro and in Situ Ruminal Degradability and Intestinal Digestibility of Feather Meal Protein. Small Rumin. Res. 2023, 226, 107024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abid, K.; Jabri, J.; Yaich, H.; Malek, A.; Rekhis, J.; Kamoun, M. Nutritional Value Assessments of Peanut Hulls and Valorization with Exogenous Fibrolytic Enzymes Extracted from a Mixture Culture of Aspergillus Strains and Neurospora intermedia. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 2024, 14, 11977–11985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOAC. Official Methods of Analysis; Association of Official Analytical Chemists: Arlington, VA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Van Soest, P.J.; Robertson, J.B.; Lewis, B.A. Methods for Dietary Fiber, Neutral Detergent Fiber, and Nonstarch Polysaccharides in Relation to Animal Nutrition. J. Dairy Sci. 1991, 74, 3583–3597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singleton, V.L.; Orthofer, R.; Lamuela-Raventós, R.M. Analysis of Total Phenols and Other Oxidation Substrates and Antioxidants by Means of Folin-Ciocalteu Reagent. In Methods in Enzymology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1999; Volume 299, pp. 152–178. ISBN 978-0-12-182200-2. [Google Scholar]

- Petchidurai, G.; Nagoth, J.A.; John, M.S.; Sahayaraj, K.; Murugesan, N.; Pucciarelli, S. Standardization and Quantification of Total Tannins, Condensed Tannin and Soluble Phlorotannins Extracted from Thirty-Two Drifted Coastal Macroalgae Using High Performance Liquid Chromatography. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2019, 7, 100273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makkar, H.P.S.; Francis, G.; Becker, K. Bioactivity of Phytochemicals in Some Lesser-Known Plants and Their Effects and Potential Applications in Livestock and Aquaculture Production Systems. Animal 2007, 1, 1371–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Research Council (Ed.) Nutrient Requirements of Dairy Cattle, 7th ed.; Nutrient Requirements of Domestic Animals; National Academy Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2001; ISBN 978-0-309-06997-7. [Google Scholar]

- Menke, K.H.; Steingass, H. Estimation of the Energetic Feed Value Obtained from Chemical Analysis and in Vitro Gas Production Using Rumen Fluid. Anim. Res. Dev. 1988, 28, 7–55. [Google Scholar]

- Theodorou, M.K.; Williams, B.A.; Dhanoa, M.S.; McAllan, A.B.; France, J. A Simple Gas Production Method Using a Pressure Transducer to Determine the Fermentation Kinetics of Ruminant Feeds. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 1994, 48, 185–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- France, J.; Dijkstra, J.; Dhanoa, M.S.; Lopez, S.; Bannink, A. Estimating the Extent of Degradation of Ruminant Feeds from a Description of Their Gas Production Profiles Observed in Vitro: Derivation of Models and Other Mathematical Considerations. Br. J. Nutr. 2000, 83, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galyean, M.L. Laboratory Procedures in Animal Nutrition Research; Department of Animal and Food Sciences Texas Tech University: Lubbock, TX, USA, 2010; Available online: https://www.depts.ttu.edu/afs/home/mgalyean/lab_man.pdf (accessed on 11 October 2025).

- Lima, P.M.T.; Moreira, G.D.; Sakita, G.Z.; Natel, A.S.; Mattos, W.T.; Gimenes, F.M.A.; Gerdes, L.; McManus, C.; Abdalla, A.L.; Louvandini, H. Nutritional Evaluation of the Legume Macrotyloma axillare Using in Vitro and in Vivo Bioassays in Sheep. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2018, 102, e669–e676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, A.K.; Kamra, D.N.; Agarwal, N. Effect of Plant Extracts on in Vitro Methanogenesis, Enzyme Activities and Fermentation of Feed in Rumen Liquor of Buffalo. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2006, 128, 276–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, T.M.; Bhat, K.M. Methods for Measuring Cellulase Activities. In Methods in Enzymology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1988; Volume 160, pp. 87–112. ISBN 978-0-12-182061-9. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, M.J.; Biely, P.; Poutanen, K. Interlaboratory Testing of Methods for Assay of Xylanase Activity. J. Biotechnol. 1992, 23, 257–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamano, Y.; Takahashi, T.; Agematu, H. Effects of Micronised Wood Powder Irradiated with Ultraviolet Light and Exposed to Ozone Gas on in Vitro Ruminal Fermentation in Beef Cattle. Anim. Husb. Dairy Vet. Sci. 2017, 1, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maheri-Sis, N.; Esmaeili-Marchubeh, M.K.; Aghajanzadeh-Golshani, A.; Safaei, A.R.; Tavakkoly-Moghaddam, B. Evaluating the Effects of Ozonation Pretreatment on Ruminal Fermentation Kinetics and Nutritive Value of Wheat Straw Using in Vitro Techniques. Indian J. Anim. Sci. 2025, 95, 251–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadnezhad, B.; Pirmohammadi, R.; Alijoo, Y.; Khalilvandi-Behroozyar, H.; Abdi-Benmar, H.; Tirado-González, D.N.; Hernández Ruiz, P.E.; Ordoñez, V.V.; Lackner, M.; Salem, A.Z.M. The Effects of Dietary Supplementation with Red Grape Pomace Treated with Ozone Gas on Ruminal Fermentation Activities, Nutrient Digestibility, Lactational Performance, and Blood Metabolites in Dairy Ewes. J. Agric. Food Res. 2024, 18, 101452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miron, J.; Yokoyama, M.T. Ozone-Treated Lucerne Hay as a Model to Study Lucerne Degradation and Utilization by Rumen Bacteria. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 1990, 27, 269–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Ghedalia, D.; Miron, J. The Effect of Combined Chemical and Enzyme Treatments on the Saccharification and in Vitro Digestion Rate of Wheat Straw. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 1981, 23, 823–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oba, M.; Allen, M.S. Evaluation of the Importance of the Digestibility of Neutral Detergent Fiber from Forage: Effects on Dry Matter Intake and Milk Yield of Dairy Cows. J. Dairy Sci. 1999, 82, 589–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Xiong, B.; Zhao, X. Could Propionate Formation Be Used to Reduce Enteric Methane Emission in Ruminants? Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 855, 158867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apajalahti, J.; Vienola, K.; Raatikainen, K.; Holder, V.; Moran, C.A. Conversion of Branched-Chain Amino Acids to Corresponding Isoacids—An in Vitro Tool for Estimating Ruminal Protein Degradability. Front. Vet. Sci. 2019, 6, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xin, H.; Khan, N.A.; Liu, X.; Jiang, X.; Sun, F.; Zhang, S.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X. Profiles of Odd- and Branched-Chain Fatty Acids and Their Correlations with Rumen Fermentation Parameters, Microbial Protein Synthesis, and Bacterial Populations Based on Pure Carbohydrate Incubation in Vitro. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 733352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, P.R.K.; Hyder, I. Ruminant Digestion. In Textbook of Veterinary Physiology; Das, P.K., Sejian, V., Mukherjee, J., Banerjee, D., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2023; pp. 353–366. ISBN 978-981-19940-9-8. [Google Scholar]

- Barros, R.D.R.O.D.; Paredes, R.D.S.; Endo, T.; Bon, E.P.D.S.; Lee, S.-H. Association of Wet Disk Milling and Ozonolysis as Pretreatment for Enzymatic Saccharification of Sugarcane Bagasse and Straw. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 136, 288–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Cubero, M.T.; González-Benito, G.; Indacoechea, I.; Coca, M.; Bolado, S. Effect of Ozonolysis Pretreatment on Enzymatic Digestibility of Wheat and Rye Straw. Bioresour. Technol. 2009, 100, 1608–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Treatments | SEM | p Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | O3 | EFE | O3 + EFE | |||

| CP | 188 b | 212 a | 190 b | 211 a | 4.3 | ** |

| EE | 38 | 35 | 37 | 37 | 1.1 | NS |

| NDF | 594 a | 536 b | 588 a | 500 c | 14.1 | ** |

| ADF | 442 a | 411 b | 442 a | 390 c | 6.2 | ** |

| ADL | 106 a | 89 b | 101 a | 88 b | 4.1 | * |

| Ash | 71 | 67 | 70 | 68 | 3.4 | NS |

| NFC | 109 c | 150 b | 115 c | 184 a | 9.3 | *** |

| TP | 15.2 a | 12.1 b | 15.0 a | 12.1 b | 1.22 | ** |

| TT | 10.1 a | 6.5 b | 9.9 a | 6.3 b | 0.81 | *** |

| CT | 3.3 a | 1.6 b | 3.3 a | 1.5 b | 0.41 | *** |

| Parameter | Treatments | SEM | p Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | O3 | EFE | O3 + EFE | |||

| PGP | 289 c | 334 b | 300 c | 378 a | 10.2 | *** |

| C | 3.31 b | 3.61 a | 3.32 b | 3.77 a | 0.181 | ** |

| Lag | 0.98 a | 0.34 b | 0.93 a | 0.31 b | 0.107 | ** |

| Parameter | Treatments | SEM | p Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | O3 | EFE | O3 + EFE | ||||

| Fermentation parameters | pH | 6.69 a | 6.65 a | 6.68 a | 6.57 b | 0.032 | * |

| NH3-N | 221 b | 251 a | 225 b | 249 a | 8.4 | ** | |

| Total VFA | 104.3 c | 118.2 b | 105.1 c | 125.2 a | 2.22 | *** | |

| VFA profile (% of total VFA) | Acetate | 68.7 b | 63.5 b | 68.6 a | 62.5 b | 2.12 | * |

| Propionate | 20.4 b | 24.1 a | 20.6 b | 24.3 a | 0.93 | *** | |

| Butyrate | 6.8 | 6.6 | 6.6 | 6.3 | 0.51 | NS | |

| Isobutyrate | 1.7 b | 2.3 a | 1.7 b | 2.4 a | 0.18 | * | |

| Isovalerate | 1.5 b | 1.9 a | 1.6 b | 2.0 a | 0.13 | * | |

| Valerate | 0.9 b | 1.4 a | 0.9 b | 1.5 a | 0.11 | * | |

| Acetate/Propionate Ratio | 3.4 a | 2.6 b | 3.3 a | 2.5 b | 0.09 | * | |

| Degradability (g/kg) | DMD | 571 c | 636 b | 586 c | 684 a | 13.1 | ** |

| NDFD | 447 c | 509 b | 453 c | 544 a | 9.4 | ** | |

| Parameter | Treatments | SEM | p Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | O3 | EFE | O3 + EFE | ||||

| Microbiota population | Bacteria (×108 cells/mL) | 12.3 c | 15.9 b | 12.2 c | 18.2 a | 1.07 | ** |

| Protozoa (×105 cells/mL) | 3.41 | 3.48 | 3.44 | 3.50 | 0.51 | NS | |

| Enzyme activity | Xylanase (U/mL) | 1.44 c | 1.74 b | 1.51 c | 1.94 a | 0.11 | ** |

| Endoglucanase (U/mL) | 5.33 c | 6.34 b | 5.32 c | 6.98 a | 0.36 | * | |

| Exoglucanase (U/mL) | 27.44 b | 30.20 a | 27.49 b | 31.44 a | 1.33 | * | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abid, K. Valorization of Artichoke Wastes via Ozonation Pretreatment and Enzyme Fibrolytic Supplementation: Effect on Nutritional Composition, Ruminal Fermentation and Degradability. Fermentation 2025, 11, 626. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation11110626

Abid K. Valorization of Artichoke Wastes via Ozonation Pretreatment and Enzyme Fibrolytic Supplementation: Effect on Nutritional Composition, Ruminal Fermentation and Degradability. Fermentation. 2025; 11(11):626. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation11110626

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbid, Khalil. 2025. "Valorization of Artichoke Wastes via Ozonation Pretreatment and Enzyme Fibrolytic Supplementation: Effect on Nutritional Composition, Ruminal Fermentation and Degradability" Fermentation 11, no. 11: 626. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation11110626

APA StyleAbid, K. (2025). Valorization of Artichoke Wastes via Ozonation Pretreatment and Enzyme Fibrolytic Supplementation: Effect on Nutritional Composition, Ruminal Fermentation and Degradability. Fermentation, 11(11), 626. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation11110626