Impact of Activated Carbon Modification on the Ion Removal Efficiency in Flow Capacitive Deionization

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Materials

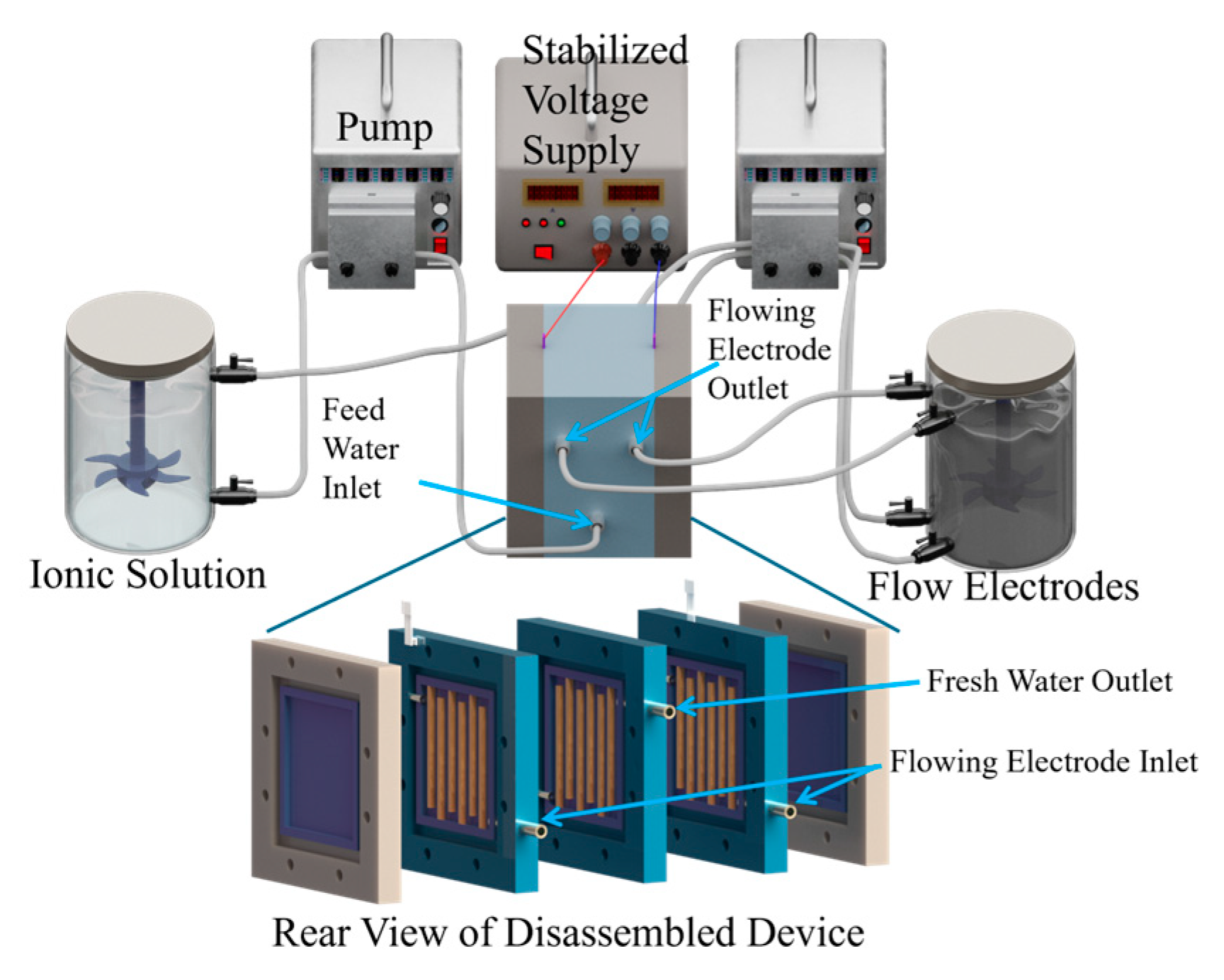

2.2. Apparatus

2.3. Modification of Active Materials and Preparation of Flow Electrodes

2.4. Characterizations

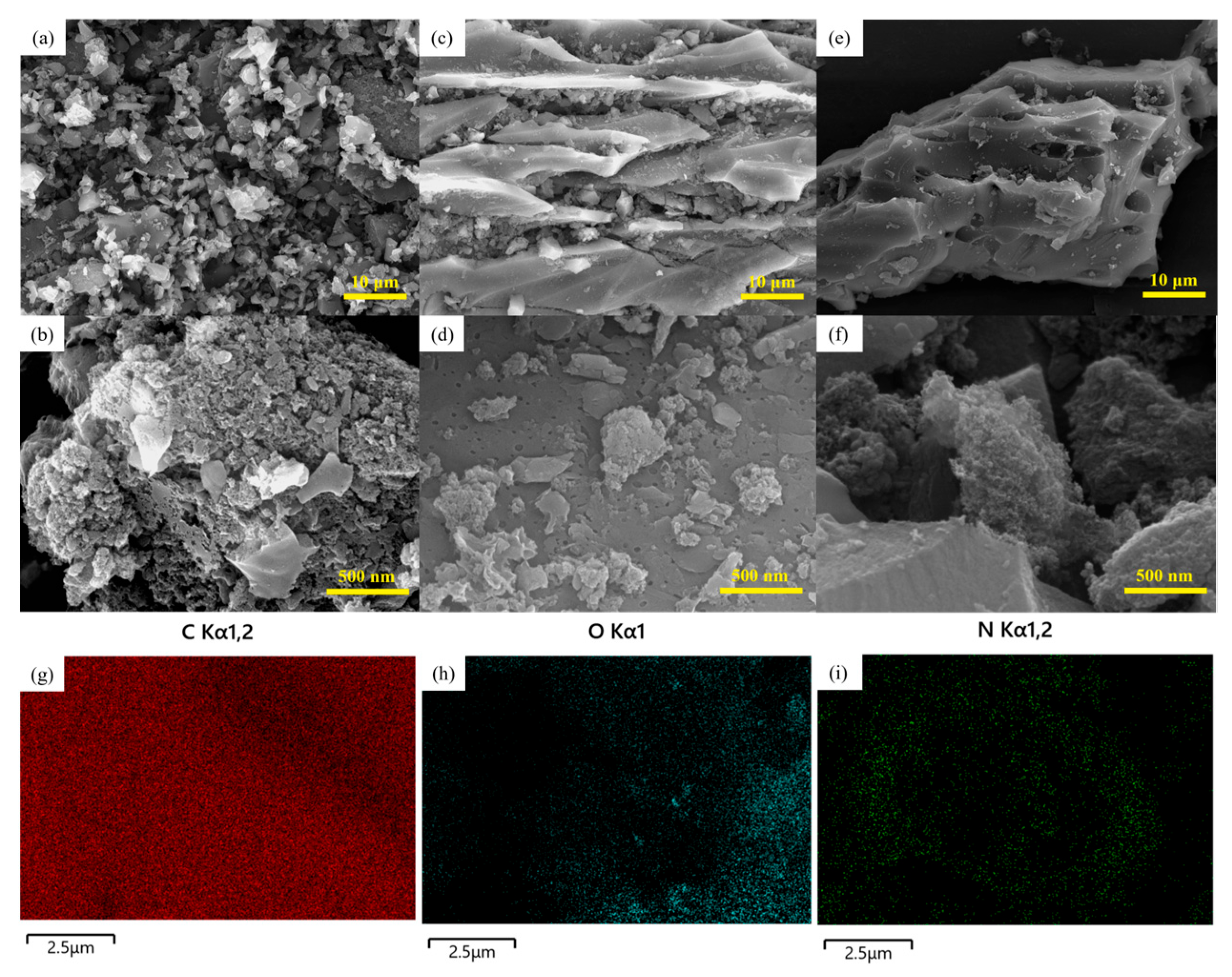

2.4.1. Scanning Electron Microscope Analysis

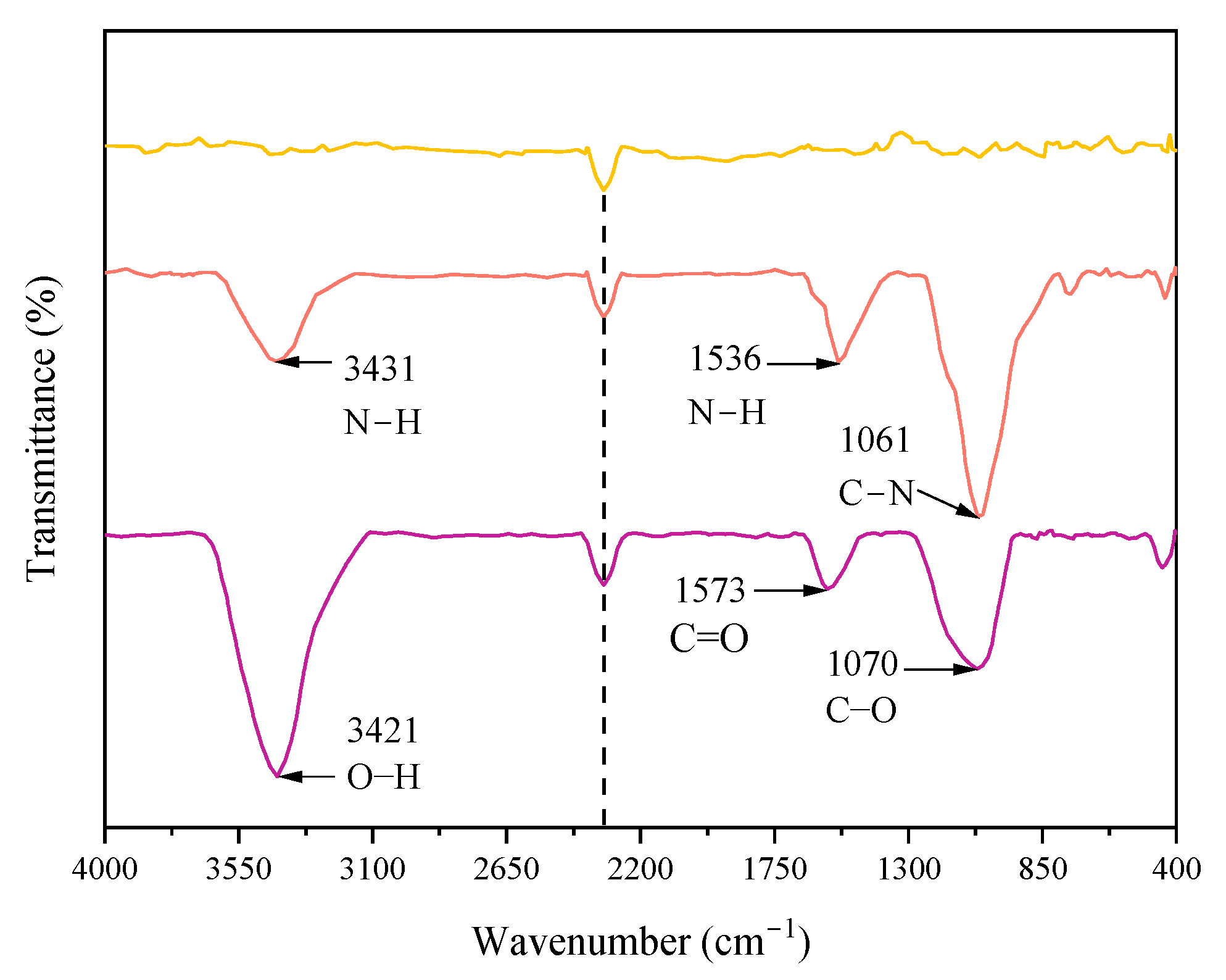

2.4.2. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy Analysis

2.4.3. Specific Surface Area and Pore Volume Analysis

2.4.4. Surface Functional Group Determination

2.4.5. Dispersion Stability Testing

2.4.6. Conductivity Testing

2.4.7. Cyclic Voltammetry

2.4.8. Deionization Performance Analysis

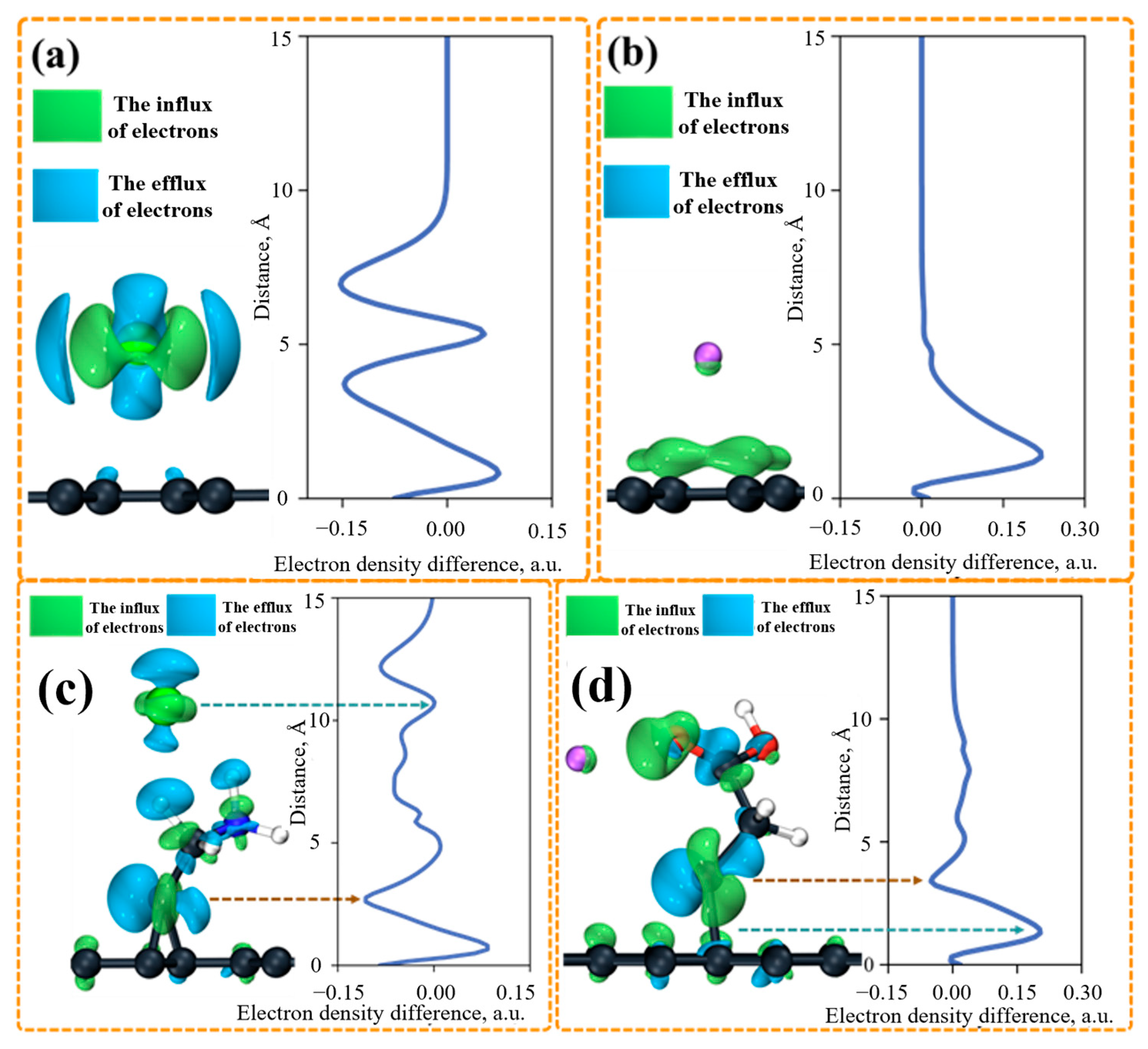

2.4.9. Simulation Calculation

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Structural Properties and Surface Morphology of Modified Activated Carbon

3.1.1. Alterations in the Functional Groups of Active Material

3.1.2. Micromorphological Analysis of Active Materials

3.1.3. Dispersion Stability of Active Materials

3.1.4. Electrochemical Analysis of Active Materials

3.2. Effect of SDS and CTAB Content on the Performance of Flow Electrodes

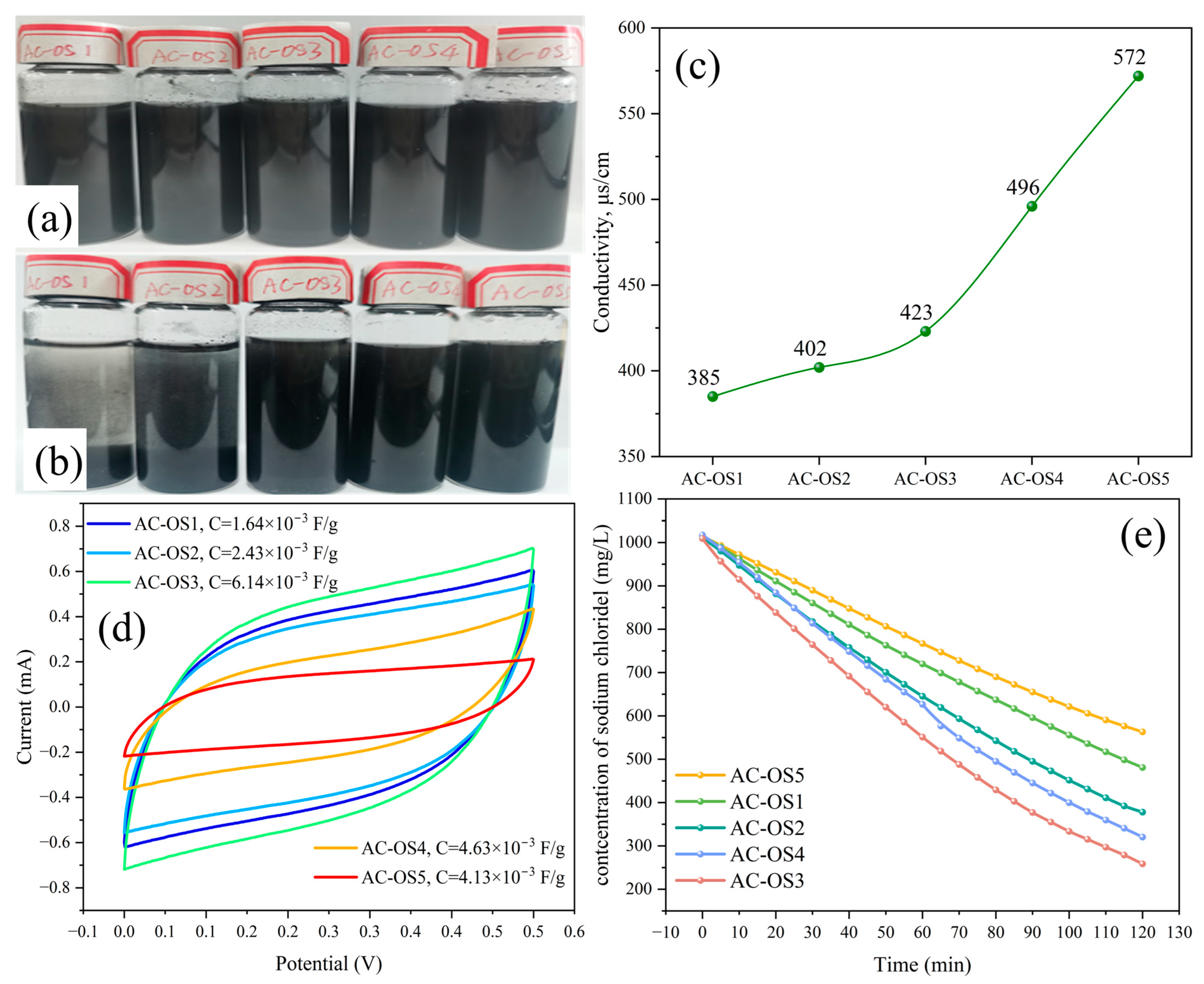

3.2.1. Dispersion Stability Analysis of Flow Electrodes

3.2.2. Electrochemical Analysis of Active Materials Incorporating Surfactants

3.3. Effect of SDS Content on the Performance of Flow Electrodes

3.3.1. Dispersion Stability Analysis of SDS/AC-O

3.3.2. Electrochemical Analysis of SDS/AC-O

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ha, Y.; Lee, H.; Yoon, H.; Shin, D.; Ahn, W.; Cho, N.; Han, U.; Hong, J.; Tran, N.A.T.; Yoo, C.-Y.; et al. Enhanced salt removal performance of flow electrode capacitive deionization with high cell operational potential. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2021, 254, 117500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biesheuvel, P.M.; van der Wal, A. Membrane capacitive deionization. J. Membr. Sci. 2010, 346, 256–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.-U.; Lim, J.; Boo, C.; Hong, S. Improving the feasibility and applicability of flow-electrode capacitive deionization (FCDI): Review of process optimization and energy efficiency. Desalination 2021, 502, 114930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Ma, J.; Wu, L.; Sun, J.; Wang, L.; Li, T.; Waite, T.D. Flow Electrode Capacitive Deionization (FCDI): Recent Developments, Environmental Applications, and Future Perspectives. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 4243–4267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J.; Zhai, C.; Yu, F. Review of flow electrode capacitive deionization technology: Research progress and future challenges. Desalination 2023, 564, 116701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Fang, D.; Huo, S.; Song, X.; He, M.; Zhang, W.; Li, K. Exceptional capacitive deionization desalination performance of hollow bowl-like carbon derived from MOFs in brackish water. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2021, 278, 119550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suss, M.E.; Baumann, T.F.; Bourcier, W.L.; Spadaccini, C.M.; Rose, K.A.; Santiago, J.G.; Stadermann, M. Capacitive desalination with flow-through electrodes. Energy Environ. Sci. 2012, 5, 9511–9519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastening, B. Properties of Slurry Electrodes from Activated Carbon Powder. Berichte Der Bunsenges. Für Phys. Chem. 1988, 92, 1399–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, S.-i.; Park, H.-r.; Yeo, J.-g.; Yang, S.; Cho, C.H.; Han, M.H.; Kim, D.K. Desalination via a new membrane capacitive deionization process utilizing flow-electrodes. Energy Environ. Sci. 2013, 6, 1471–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chand, H.; Liu, Z.; Wei, Q.; Gaballah, M.S.; Li, W.; Osmolovskaya, O.; Podurets, A.; Voznesenskiy, M.; Pismenskaya, N.; Padhye, L.P.; et al. Performance and mechanism of chromium removal using flow electrode capacitive deionization (FCDI): Validation and optimization. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 340, 126696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Hu, X.; Zhang, X.; Chang, Q.; Wang, Y. Reduced graphene oxide modified porous alumina substrate as an electrode material for efficient capacitive deionization. J. Porous Mater. 2023, 30, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Mao, Y.; Zong, Y.; Wu, D. Scale-up desalination: Membrane-current collector assembly in flow-electrode capacitive deionization system. Water Res. 2021, 190, 116782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Yu, C.; Tian, S.; Mao, Y.; Zong, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, C.; Wu, D. Selective Recovery of Phosphorus from Synthetic Urine Using Flow-Electrode Capacitive Deionization (FCDI)-Based Technology. ACS EST Water 2021, 1, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatzell, K.B.; Hatzell, M.C.; Cook, K.M.; Boota, M.; Housel, G.M.; McBride, A.; Kumbur, E.C.; Gogotsi, Y. Effect of Oxidation of Carbon Material on Suspension Electrodes for Flow Electrode Capacitive Deionization. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 3040–3047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Wang, P.; Xue, W.; Zhang, W.; Liu, F.; Yang, C.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, C. Symmetric anion exchange membranes enhance arsenic removal and overcome conductivity limitations in FCDI systems. NPJ Clean Water 2025, 8, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, L.; Sui, X.; Tian, S.; Liu, X.; Ma, S.; Liu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Ying, A. Semi-anchored percolation networks for low-threshold and selective desalination in FCDI. Desalination 2025, 616, 119417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Sun, J.; Jiao, Y.; Tan, T.; Zhang, Y.; Diao, H.; Xia, S. Enhanced Fluoride Removal in Wastewater Using Modified Activated Carbon in FCDI Systems. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2024, 235, 530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Qin, F.; Lai, L.; Qin, C.; Wang, R. Performance of fluorine removal using flow electrode capacitive deionization (FCDI): Validation and optimization. Environ. Technol. 2025, 46, 4407–4416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goertzen, S.L.; Thériault, K.D.; Oickle, A.M.; Tarasuk, A.C.; Andreas, H.A. Standardization of the Boehm titration. Part I. CO2 expulsion and endpoint determination. Carbon 2010, 48, 1252–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Zhao, S.; Zhou, S.; Xu, Z. How the Thermal Effect Regulates Cyclic Voltammetry of Supercapacitors. ACS Energy Lett. 2023, 8, 3365–3372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Zhou, C.; Xu, S.; Yang, K.; Liu, G.; Li, X. Ultrasound-improved removal of chloride ions from coking circulating water by Friedel’s salt precipitation: Efficiency enhancement and mechanisms. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2024, 189, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdew, J.P.; Burke, K.; Ernzerhof, M. Generalized Gradient Approximation Made Simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996, 77, 3865–3868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hutter, J.; Iannuzzi, M.; Schiffmann, F.; VandeVondele, J. cp2k: Atomistic simulations of condensed matter systems. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 2014, 4, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.; Chen, F. Multiwfn: A multifunctional wavefunction analyzer. J. Comput. Chem. 2012, 33, 580–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, G.; Lee, K.B.; Ham, H.C. Effect of N-Containing Functional Groups on CO2 Adsorption of Carbonaceous Materials: A Density Functional Theory Approach. J. Phys. Chem. C 2016, 120, 8087–8095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Liu, G.; Zhang, G. Effect of strain on the photoelectric properties of molybdenum ditelluride under vacancy defects: A DFT investigation. J. Mol. Model. 2024, 30, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Deng, Q.; Guo, Z.; Seok, I. Modification of coconut shell activated carbon and purification of volatile organic waste gas acetone. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 2022, 5, 491–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Wu, H.; Liu, L.-B.; Pan, H.-C.; Liu, H. Effects of 2-ethylbutyric acid, 2-ethyl-1-butanol, and 3-methylpentane on the micellization thermodynamics and physicochemical properties of HS 15 and TW 80 micelles based on differences in functional groups. J. Mol. Liq. 2024, 413, 126003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; An, M.; Chen, D.; Yuan, Y.; Xu, X.; Sharshir, S.W.; Yuliarto, B.; Zhu, F.; Sun, X.; Gao, S.; et al. Molecular insights into enhanced water evaporation from a hybrid nanostructured surface with hydrophilic and hydrophobic domains. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 465, 142838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, P.; Panwar, A.S.; Bahadur, D. Molecular-Level Insights into the Stability of Aqueous Graphene Oxide Dispersions. J. Phys. Chem. C 2017, 121, 9847–9859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seredych, M.; Hulicova-Jurcakova, D.; Lu, G.Q.; Bandosz, T.J. Surface functional groups of carbons and the effects of their chemical character, density and accessibility to ions on electrochemical performance. Carbon 2008, 46, 1475–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Chen, N.; Ren, H.-L.; Li, C.-W.; Guo, L.-L.; Li, Z.; Wang, X.-M. Application of modified graphite felt as electrode material: A review. Carbon Lett. 2023, 33, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A.; Michalska, M.; Zaszczyńska, A.; Denis, P. Surface modification of activated carbon with silver nanoparticles for electrochemical double layer capacitors. J. Energy Storage 2022, 54, 105367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.T.; Gollas, B.; Abbas, Q. Differentiating ion transport of water-in-salt electrolytes within micro- and meso-pores of a multiporous carbon electrode. J. Mater. Chem. A 2024, 12, 25504–25518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yumak, T.; Bragg, D.; Sabolsky, E.M. Effect of synthesis methods on the surface and electrochemical characteristics of metal oxide/activated carbon composites for supercapacitor applications. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 469, 983–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, R.L.; Little, R.C. Interaction of sodium dodecyl sulphate and polyethylene oxide. Nature 1975, 253, 36–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y.; Xu, M.; Li, M.; Jin, W.; Cao, Y.; Gui, X. Role of DTAB and SDS in Bubble-Particle Attachment: AFM Force Measurement, Attachment Behaviour Visualization, and Contact Angle Study. Minerals 2018, 8, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, G.P.; Martins, C.; Fortuny, M.; Santos, A.F.; Turmine, M.; Graillat, C.; McKenna, T.F.L. In-Line and In Situ Monitoring of Ionic Surfactant Dynamics in Latex Reactors Using Conductivity Measurements and Ion-Selective Electrodes. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2007, 46, 1465–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Singh, V.; Behrens, S.H. Electric Charging in Nonpolar Liquids Because of Nonionizable Surfactants. Langmuir 2010, 26, 3203–3207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Samples | Carboxylic Acid (mmol/g) | Surface Basicity (mmol/g) |

|---|---|---|

| AC | 0.11 | 0.73 |

| AC-O | 0.26 | 0.55 |

| AC-N | 0.09 | 1.31 |

| Samples | Carbon (wt%) | Oxygen (wt%) | Nitrogen (wt%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| AC | 98.12 | 1.88 | 0.00 |

| AC-O | 92.35 | 7.65 | 0.00 |

| AC-N | 91.86 | 5.54 | 2.60 |

| Samples | SBET (m2/g) | V (cm3/g) | Vmic (cm3/g) | Pore Size (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AC | 1056.82 | 0.51 | 0.32 | 1.93 |

| AC-O | 1071.90 | 0.52 | 0.41 | 1.82 |

| AC-N | 122.75 | 0.11 | 0.04 | 3.15 |

| Samples | Desalination Ratio (%) | Desalination Rate (mg·L−1·min−1) |

|---|---|---|

| AC | 12.98 | 1.0934 |

| AC-O | 23.28 | 1.9681 |

| AC-O/CTAB | 50.24 | 4.2030 |

| AC-O/SDS | 74.37 | 6.2542 |

| AC-N | 17.53 | 1.4739 |

| AC-N/SDS | 47.99 | 4.0018 |

| AC-N/CTAB | 63.21 | 5.2351 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Qiao, W.-H.; Liu, Y.-N.; Li, Y.; Xie, Y.; Yang, H.-Y.; Hou, J.-W. Impact of Activated Carbon Modification on the Ion Removal Efficiency in Flow Capacitive Deionization. C 2025, 11, 90. https://doi.org/10.3390/c11040090

Qiao W-H, Liu Y-N, Li Y, Xie Y, Yang H-Y, Hou J-W. Impact of Activated Carbon Modification on the Ion Removal Efficiency in Flow Capacitive Deionization. C. 2025; 11(4):90. https://doi.org/10.3390/c11040090

Chicago/Turabian StyleQiao, Wen-Huan, Ya-Ni Liu, Ya Li, Yu Xie, Hai-Yi Yang, and Jun-Wei Hou. 2025. "Impact of Activated Carbon Modification on the Ion Removal Efficiency in Flow Capacitive Deionization" C 11, no. 4: 90. https://doi.org/10.3390/c11040090

APA StyleQiao, W.-H., Liu, Y.-N., Li, Y., Xie, Y., Yang, H.-Y., & Hou, J.-W. (2025). Impact of Activated Carbon Modification on the Ion Removal Efficiency in Flow Capacitive Deionization. C, 11(4), 90. https://doi.org/10.3390/c11040090