1. Introduction

Heavy oil processing is directly associated with energy generation systems, such as in power plants, combustion processes, and fluid catalytic cracking (FCC) units [

1]. In such applications, the oil is dispersed in the form of a spray to increase the specific liquid surface area and thus enhance heat and mass transfer phenomena. For instance, in FCC units, crude oil is dispersed inside the reactor and subsequently converted through catalytic cracking into valuable petrochemical products such as jet fuel, diesel, gasoline, and hydrocarbons [

2]. Consequently, understanding and improving oil atomization carries significant environmental and economic importance in fuel production.

The category of heavy oils encompasses a wide range of high-viscosity fuels, including residual oils and naphtha, which are challenging to atomize effectively and require specially designed nozzles for these industrial processes. In this context, specific strategies have been employed to facilitate the dispersion of such viscous liquids, such as oil pre-heating [

3] and using a dispersing medium, typically compressed air or superheated steam, to assist in atomization [

4].

The use of auxiliary gas in twin-fluid atomizers offers advantages in the nozzle operation compared with single-fluid atomizers, such as lower operating pressures for efficient atomization of viscous liquids [

5]. Further atomization improvement, i.e., droplet size reduction, is achieved by optimizing the nozzle geometry and tailoring the operating conditions [

6,

7]. These measures contribute to achieving an acceptable gas emission level and proper plant operation [

8,

9,

10].

Typical atomizers used in industrial power plants include the T-jet and Y-jet nozzles. They are classified as internal-mixing nozzles and are particularly well-suited for atomizing viscous liquids at high operating loads because they use a high-speed gas stream and promote an intense gas–liquid mixing within the nozzle chamber. This design is preferred for use in fluid catalytic cracking units in comparison with other twin-fluid atomizers, such as effervescent atomizers, because they feature a simple geometry, offer easy and cheap maintenance, and are less prone to clogging due to coke formation from the contact of heavy oil with steam.

In internal-mixing nozzles, shear-driven atomization is the dominant breakup mechanism in comparison with pressure atomization or impact. The high-velocity gas stream interacts with the surface of the relatively slow-moving liquid, inducing Kelvin–Helmholtz instabilities and forming surface waves that detach from the bulk liquid, producing ligaments and then primary droplets.

A key feature distinguishing these two nozzle designs is the impingement angle between the gas and the liquid injection ports. In T-jet nozzles, the liquid enters perpendicularly (at a 90° angle) to the central gas stream, while in Y-jet nozzles, the inlets of the fluids converge at a smaller angle. As the gas flows into the mixing chamber, it exerts an additional shear force on the liquid stream, pushing it toward the nozzle outlet and promoting liquid disintegration.

The liquid penetration into the mixing chamber and its interaction with the gas stream are governed by the liquid-to-gas momentum ratio (

) defined in Equation (1):

where

is the gas-to-liquid mass flow rate ratio, and

and

are the gas and liquid densities, respectively, calculated at the respective fluid inlet port diameter, represented by

and

for gas and liquid.

represents the port angle of the Y-jet configuration.

The

magnitude represents the relative injection force of the liquid compared to that of the gas stream [

11,

12]. This parameter is decisive for the local liquid distribution in different regions of the spray, as, for instance, measured with a patternator device [

13]. This spray characteristic directly impacts the spatial distribution of droplet sizes and velocities [

14]. Spray regions with lower liquid mass flux typically present smaller droplet sizes because of the velocity difference between the gas and the liquid, inducing further liquid breakup [

12].

The parameter

was initially formulated for Y-jet nozzles with two inlet ports to the mixing chamber (one central gas port and an angled lateral liquid injection) [

15]. When the liquid jets have lower momentum than the gas (

1), the liquid jet is deflected toward the chamber walls, forming an annular flow pattern characterized by a thicker liquid film on the same side as its inlet. In this regime, the gas stream occupies the central region of the mixing chamber, promoting limited interaction with the liquid, which remains mostly attached to the walls [

16].

A momentum ratio in the range 1

3 implies equivalent gas and liquid forces, indicating that the liquid penetrates further into the mixing chamber center. Consequently, the gas interaction with the liquid is not limited to the free surface of the liquid film attached to the wall (as for

1) but implies more intense mixing and shear stress imposed by the high-speed gas jet, creating a relatively finer spray. However, under certain conditions, this regime can occasionally lead to an oscillatory two-phase flow behavior, because the liquid restricts the region available for the gas jet expansion when it flows from the gas inlet port to the mixing chamber. This gas obstruction causes a pressure buildup and liquid accumulation inside the mixing chamber, which eventually leads to the abrupt ejection of a liquid chunk from the mixing chamber, characterizing the pulsed spray formation [

5,

17].

This pulsation process repeats periodically during the atomization process, and the frequency is dependent on the nozzle geometry and operating conditions. However, this unstable nozzle operation is detrimental to the atomization process because it produces a broad variation in droplet size and velocity, and it provides uneven liquid distribution in the spray. Such irregularities compromise the subsequent catalytic cracking reaction in FCC units, which may form undesired byproducts, in addition to adversely affecting the temperature distribution inside the reactor.

Further increasing the momentum ratio 3 results in a liquid jet with enough momentum to gradually cross the entire mixing chamber cross-section. In these cases, the blocking effect on the gas becomes more evident because it is deflected to the internal chamber edges and must flow around the liquid column. This regime is characteristic of low and forms a continuous central liquid core.

Some studies have characterized the effect of the pulsed nozzle operation on the spray development [

18]. In Barbieri et al. [

19], two main spray oscillation patterns that correlate with the internal-mixing chamber pressure have been observed. At high

and, consequently, low internal pressure, typically corresponding to

1, the spray center emerging from the nozzle consists of a fine liquid mist. Here, liquid ligaments and droplets locally detach from the spray core due to the collapse of gas bubbles. Conversely, at low

, higher internal pressures intensify the bubble collapse, expelling liquid lumps from the nozzle and causing the characteristic pulsed spray motion observed in Y-jet nozzles.

Understanding the internal gas–liquid interaction in Y-jet nozzles is essential for mitigating pulsed spray behavior, which can be achieved through appropriate modifications in the nozzle design or operating conditions. Accordingly, the aim of this work is to elucidate the onset and evolution of the pulsed spray operation in a specific design of the internal-mixing Y-jet nozzle. To achieve this, a detailed numerical simulation of the internal mixing process is validated against experimental pressure measurements obtained inside the nozzle. The simulations are used to describe, both quantitatively and qualitatively, the interaction dynamics between the liquid and gas streams within the mixing chamber, using water and air as working fluids. Based on the flow patterns obtained numerically, recommendations are proposed to suppress or eliminate pulsed spray formation and improve nozzle performance.

2. Experimental Pressure Acquisition

The experimental methodology presented in this section describes how pressure is acquired from inside the mixing chamber. The results are used to validate the numerical simulations presented in the subsequent section. A detailed description of the experimental facility and operating conditions is given in [

19], and only relevant information regarding the nozzle construction and pressure sensors positioning is provided in this work.

The typical atomizer layout used for the steam-assisted oil atomization in the FCC reactors is shown in

Figure 1a. It features a central lance for the gas flow, with an internal diameter of 35 mm in the case of this study, while the liquid flows through an annular section, with an outer diameter of 90 mm, up to reaching the Y-jet nozzle at the atomizer tip, which is highlighted by the red dashed circle.

The internal-mixing Y-jet nozzle design consists of two liquid inlet ports positioned 180° apart, as depicted in

Figure 1b. Upon entering the mixing chamber, the two liquid jets impinge and are further disrupted by the high-speed central gas stream coming from above. The nozzle geometry features a liquid-to-gas impingement angle

= 72°, a mixing chamber length

= 34.3 mm, and an opening angle

= 10°, resulting in an outlet diameter

= 15.2 mm. The gas supply channel has a minimum diameter

= 3.6 mm at the throat, and the liquid channels have a minimum diameter

= 5.5 mm.

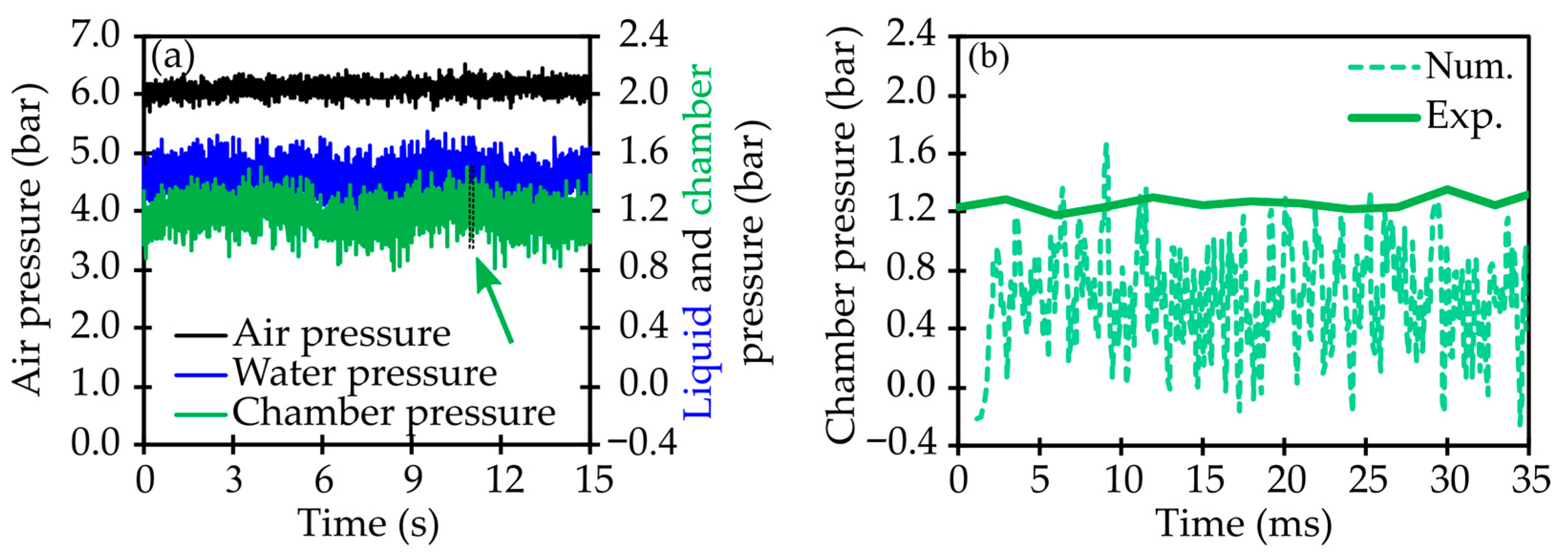

Important details about the internal mixing process can be derived from the internal pressure signal. For this, the nozzle has a central internal pressure monitoring point (

), as indicated by the green marker in

Figure 1b, which is located at

= 0.375. This pressure sensor (PT5404 from company IFM with a pressure range from 0 to 10 bar and inaccuracy < 0.5%) enables the measurement of the static pressure from the mixing chamber centerline with an acquisition frequency of 333 Hz. This point is aligned with, and is directly downstream from, the gas inlet port. It is intentionally positioned to acquire the chamber pressure in the pre-impingement region, characterized by a predominant single-phase gas flow. This enables the determination of whether a choked gas flow condition is achieved at the minimum area region in the experiments. Additionally, the gas and liquid injection pressures (

and

, respectively), are obtained from pressure sensors before their injection into the atomizer.

In this work, the experiments are conducted using water and air as working fluids. The compressed air is supplied at room temperature (21 ± 2 °C) and has its flow rate measured with the flowmeter OPTISWIRL 4200 from the company Krohne, which has an operating range of 0–650 kg/h and uncertainty of 1%. The air injection remains constant in all experiments at an absolute pressure of 7 bar, which is measured before reaching the nozzle with a PI2204 pressure sensor from the company IFM, with a range of 0 to 11 bar and a precision of 0.01 bar. The water is supplied by a centrifugal pump, and the operating condition is measured using a flowmeter (OPTISONIC 3400 C from Krohne, with a range of 0 to 8000 kg/h and an uncertainty in the measurements < 0.5%) and a pressure sensor (PT5404 from company IFM, with a pressure range from 0 to 10 bar and inaccuracy < 0.5%). The different operating conditions are obtained by varying the liquid mass flow rate while the gas injection remains constant.

3. Numerical Methodology

The numerical simulations aim to explore the mixing state promoted by the interaction of the gas and liquid phases within the internal mixing chamber. This characterization is challenging in the real facility due to the use of opaque materials when manufacturing the nozzle, such as metal. The simulations represent, and are compared with, air-assisted atomization experiments using water as the liquid. In the pre-processing stage, the geometry of the nozzle cavity (

Figure 2a) is discretized into control volumes using the software ANSYS ICEM-CFD version 19.2. A sketch of the numerical mesh used to represent the fluid inlets and the mixing chamber consists of a rectangular geometry, as shown in

Figure 2b.

The structured mesh presents a greater refinement in the central nozzle region, specifically at the gas inlet and in the impingement region between the gas and liquid streams, with elements measuring 0.1–0.3 mm, as highlighted in

Figure 2b. These elements increase in size towards the nozzle outlet, reaching a maximum of 1.6 mm.

Figure 2c indicates the nozzle dimensions in the numerical simulation, which are based on the nozzle geometry in

Figure 1b.

The pre-processing stage includes setting the boundary conditions and determining the numerical model solution strategy, which is performed using the finite volume method [

20,

21] in the software ANSYS Fluent version 19.2.

The numerical modeling of the internal multiphase flow in Y-jet atomizers assumes the continuum hypothesis, incompressible flow of the liquid phase, compressible gas flow, and no chemical reaction. The gas and liquid phases are not interpenetrating, and the interface between them in the flow is tracked with the VOF (Volume of Fluid) approach, developed by [

22].

The use of the VOF approach matches the main aim of this work, representing the overall spray behavior inside the nozzle and characterizing the interaction between the liquid and the gas streams within the nozzle cavity. The primary breakup in the nozzle cavity and droplet formation would require very fine meshes or other numerical approaches, such as LES or adaptive mesh refinement, which are more computationally expensive. In this work, a high-order interface reconstruction (Geo-Reconstruction scheme) is used to represent the interface and match the focus on the gas and liquid interaction inside the nozzle.

Accordingly, the multiphase flow can be represented by the mass conservation equation (Equation (2)) and by the linear momentum conservation equation (Equation (3)):

where

is the velocity vector,

is the fluid density,

is the static pressure,

is the gravity vector, and

is the effective viscosity defined as the sum of the molecular viscosity

and the turbulent viscosity

, according to Equation (4):

The surface tension

is modeled with the Continuum Surface Force (CSF) model. The fluids share the same transport equations in the VOF model and, as they are not interpenetrating, in each control volume, the phase volume fractions are equal to unity, as shown in Equation (5):

with

as the volume fraction of component

.

equals 0 means that the control volume is empty of the

component, and

of unity represents a control volume full of the

component, while 0

1 indicates that the control volume contains the interface of the

component with one or more other components.

A continuity equation for

represents the temporal and spatial evolution of the volume fraction without source term and mass transfer, according to Equation (6):

with

as the density of the

phase and

as the velocity vector of the

phase.

The density and molecular viscosity in Equations (2)–(4) are defined using the mixture rule, accounting for the phase volume fraction in each control volume. For a two-phase system, as the case of this study represented by indexes 1 and 2, and with the known volume fraction of phase 2,

and

are given by Equations (7) and (8), respectively. The solution of the continuity equation for the volume fraction allows for tracking the interface between the two phases:

The turbulence modeling relies on the Boussinesq hypothesis, which assumes that the Reynolds tensor in the Navier–Stokes equations is a linear function of the strain rate with the turbulent viscosity as the coefficient. The numerical investigation presented in this work calculates the turbulent viscosity using the Shear-Stress-Transport (SST) k-ω model. This model, proposed by [

23], which is based on a k-ε and k-ω blending, is applied to describe the turbulent fluid flow in the inner and outer parts of the boundary layer for a wide Reynolds number range [

21]. This model assumes the eddy viscosity hypothesis and addresses the turbulent viscosity as an effective viscosity, as shown in Equation (4). This is a reasonable alternative to more expensive approaches, such as LES or DNS, matching the main objective of this work.

Table 1 shows the standard simulation configuration. The simulations represent air as a compressible gas phase following the ideal law. It is injected into the gas inlet boundary condition (

Figure 2a) at an absolute pressure of 7 bar, corresponding to the air-assisted experiments. Water is the liquid phase, and its inlets are set to a constant velocity magnitude depending on the evaluated condition. An outlet boundary condition of prescribed pressure equal to 0 Pa is specified at the domain outlet. All walls are characterized as no-slip conditions. An adaptive time step (1

10

−7 s

1

10

−3 s) is used. The simulations are processed using ANSYS Fluent version 19.2 software, while the post-processing is carried out in CFD-Post 19.2.

Although the VOF is commonly used with incompressible or weakly compressible problems, the gas flow, especially after the gas inlet port, has compressible effects. At this point, it is important to consider modeling the gas as a compressible fluid with the energy equation enabled in this work, as presented in

Table 1.

The numerical solution uncertainty associated with the grid element size is quantified using the GCI (grid convergence index) methodology detailed in [

24]. Three meshes with different refinements have been produced to evaluate the liquid height inside the mixing chamber and the chamber pressure along the nozzle length near the internal wall as local variables. The GCI of the liquid height is lower than 3.5% along the nozzle length, while the static pressure shows a GCI generally lower than 10%. Accordingly, the intermediate mesh with approximately 85,000 elements is used for further internal flow simulation studies. This is a crucial step to ensure simulation accuracy. A more detailed analysis of the GCI method for the meshes is presented in

Appendix A.

5. Conclusions

Liquid atomization using Y-jet nozzles constitutes a fundamental role in the oil refining process. Understanding the operation of this nozzle configuration is essential for optimizing energy use, enhancing process efficiency, and reducing environmental impact by minimizing raw material consumption.

Achieving stable atomization is critical for the proper design of the refining facilities and for ensuring consistent product standards. The formation of pulsed sprays, however, is highly sensitive to the operating conditions. This study identified the mechanisms responsible for pulsed spray formation and clarified the role of gas–liquid interactions within the nozzle’s mixing chamber.

When the liquid jets enter the mixing chamber, they impose back pressure on the gas stream. Increasing the liquid-to-gas momentum ratio, i.e., reducing the gas-to-liquid mass flow ratio GLR, limits the space available for gas expansion within the chamber and escalates the internal pressure, resulting in the power-law relation between and GLR. This typical Y-jet nozzle operation causes high pressures in the nozzle cavity, especially in the pre-impingement region, which is associated with a liquid recirculation that can partially block the gas flow into the mixing chamber. Upon overcoming the obstruction established by the liquid jets, the gas stream promotes a sudden liquid mass removal from the nozzle, creating an oscillatory spray formation. As the flow develops in an expanding nozzle cavity, the pressure reduces along the nozzle cavity up to reaching the atmospheric pressure from outside the nozzle. Furthermore, at lower momentum ratios , the liquid projections alternately detach in the impingement region, while at a high momentum ratio, the flow develops more symmetrically.

The numerical model has been validated with experimental pressure measurements inside the nozzle. The comparison of the pressure magnitude agreed with the measurement values, and pressure signal oscillations have been measured and captured numerically, which are associated with the intense mixing within the nozzle. The frequency at which these oscillations occur depends on the operating conditions and decreases with the GLR. As the momentum ratio increases, more intense pressure fluctuations are observed.

These findings emphasize the importance of selecting appropriate GLR values that balance atomization efficiency and stability for specific industrial applications. A comprehensive investigation of the multiphase flow dynamics can inform the design of more efficient atomizers and guide the definition of operational windows that suppress pulsed behavior while maintaining effective atomization.