Transient Electrophoresis in Suspensions of Charged Porous Particles

Abstract

1. Introduction

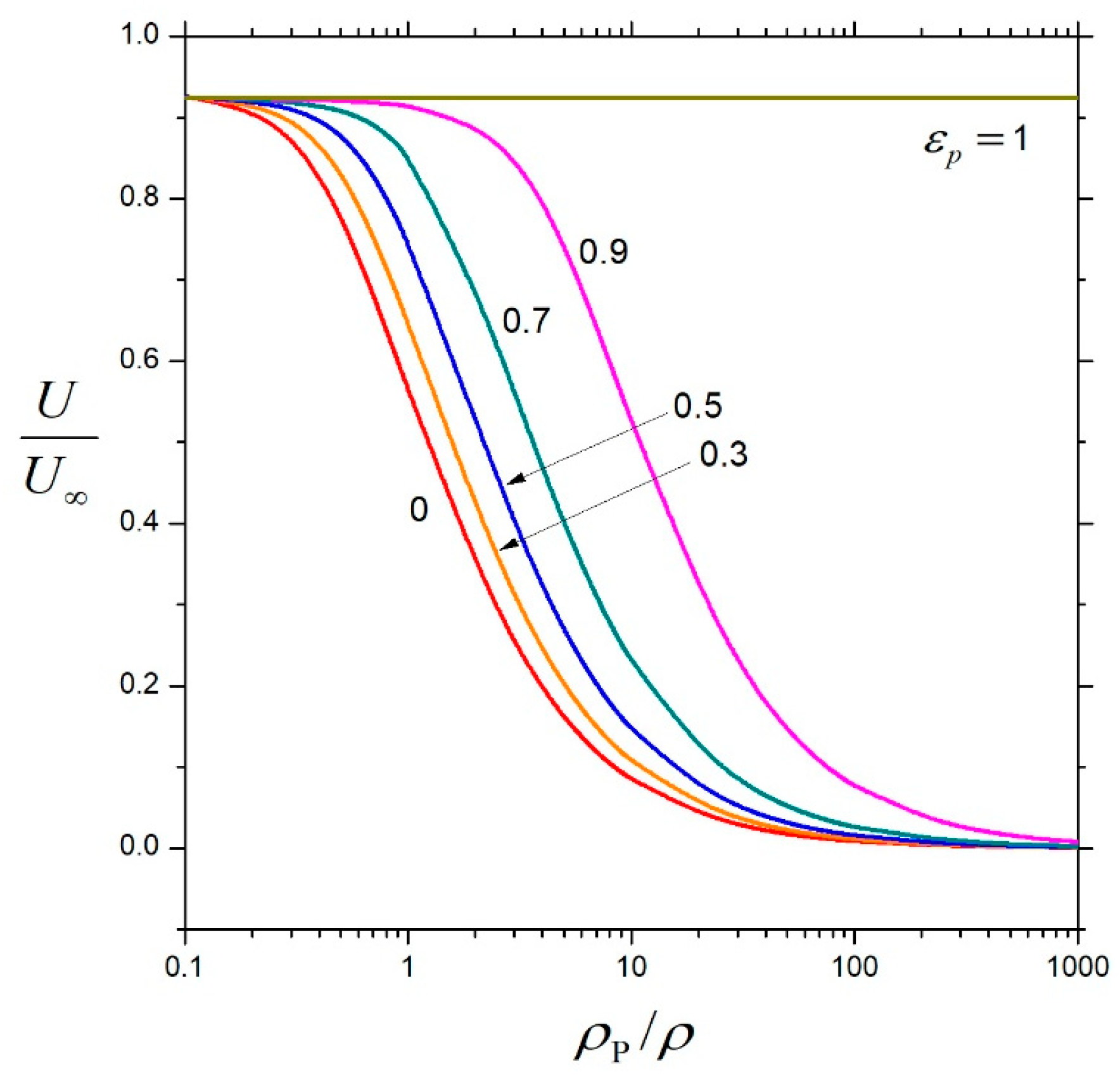

2. Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Henry, D.C. The Cataphoresis of Suspended Particles. Part I.—The Equation of Cataphoresis. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A 1931, 133, 106–129. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison, F.A. Electrophoresis of a Particle of Arbitrary Shape. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1970, 34, 210–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dukhin, S.S.; Derjaguin, B.V. Surface and Colloid Science; Matijevic, E., Ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1974; Volume 7. [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien, R.W.; White, L.R. Electrophoretic Mobility of a Spherical Colloidal Particle. J. Chem. Soc. Faraday Trans. 2 1978, 74, 1607–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohshima, H.; Healy, T.W.; White, L.R. Approximate Analytic Expressions for the Electrophoretic Mobility of Spherical Colloidal Particles and the Conductivity of Their Dilute Suspensions. J. Chem. Soc. Faraday Trans. 2 1983, 79, 1613–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, R.W. The Solution of the Electrokinetic Equations for Colloidal Particles with Thin Double Layers. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1983, 92, 204–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermans, J.J.; Fujita, H. Electrophoresis of Charged Polymer Molecules with Partial Free Drainage. Koninkl. Ned. Akad. Wetenschap. Proc. Ser. B 1955, 58, 182–187. [Google Scholar]

- Gopmandal, P.P.; Bhattacharyya, S.; Barman, B. Effect of Induced Electric Field on Migration of a Charged Porous Particle. Eur. Phys. J. E 2014, 37, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.Y.; Keh, H.J. Electrophoretic Mobility and Electric Conductivity in Suspensions of Charge-Regulating Porous Particles. Colloid Polym. Sci. 2015, 293, 1903–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majee, P.S.; Bhattacharyya, S.; Dutta, P. On Electrophoresis of a pH-Regulated Nanogel with Ion Partitioning Effects. Electrophoresis 2019, 40, 699–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duval, J.F.L.; Ohshima, H. Electrophoresis of Diffuse Soft Particles. Langmuir 2006, 22, 3533–3546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.C.; Keh, H.J. Electrophoresis and Electric Conduction in a Suspension of Charged Soft Spheres. Colloid Polym. Sci. 2016, 294, 1129–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurya, S.K.; Gopmandal, P.P.; Ohshima, H.; Duval, J.F.L. Electrophoresis of Composite Soft Particles with Differentiated Core and Shell Permeabilities to Ions and Fluid Flow. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2020, 558, 280–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivory, C.F. Transient Electrophoresis of a Dielectric Sphere. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1984, 100, 239–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmusson, M.; Akerman, B. Dynamic Mobility of DNA. Langmuir 1998, 14, 3512–3516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahualli, S.; Jimenez, M.L.; Carrique, F.; Delgado, A.V. AC Electrokinetics of Concentrated Suspensions of Soft Particles. Langmuir 2009, 25, 1986–1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ammam, M.; Fransaer, J. AC-Electrophoretic Deposition of Glucose Oxidase. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2009, 25, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khair, A.S. Transient Phoretic Migration of a Permselective Colloidal Particle. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2012, 381, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neirinck, B.; Van der Biest, O.; Vleugels, J. A Current Opinion on Electrophoretic Deposition in Pulsed and Alternating Fields. J. Phys. Chem. B 2013, 117, 1516–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrique, F.; Ruiz-Reina, E.; Roa, R.; Arroyo, F.J.; Delgado, A.V. Ionic Coupling Effects in Dynamic Electrophoresis and Electric Permittivity of Aqueous Concentrated Suspensions. Colloids Surf. A 2018, 541, 195–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohshima, H. Transient Dynamic Electrophoresis of a Soft Particle. Electrophoresis 2024, 45, 2087–2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yossifon, G.; Frankel, I.; Miloh, T. Macro-scale Description of Transient Electro-kinetic Phenomena over Polarizable Dielectric Solids. J. Fluid Mech. 2009, 620, 241–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, F.A. Transient Electrophoresis of a Dielectric Sphere. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1969, 29, 687–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keh, H.J.; Huang, Y.C. Transient Electrophoresis of Dielectric Spheres. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2005, 291, 282–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohshima, H. Transient Electrophoresis of a Spherical Soft Particle. Colloid Polym. Sci. 2022, 300, 1369–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.C.; Keh, H.J. Transient Electrophoresis of Spherical Particles at Low Potential and Arbitrary Double-Layer Thickness. Langmuir 2005, 21, 11659–11665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherief, H.H.; Faltas, M.S.; Ragab, K.E. Transient Electrophoresis of a Conducting Spherical Particle Embedded in an Electrolyte-Saturated Brinkman Medium. Electrophoresis 2021, 42, 1636–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayman, M.; Saad, E.I.; Faltas, M.S. Transient Electrophoresis of a Conducting Cylindrical Colloidal Particle Suspended in a Brinkman Medium. Z. Angew. Math. Phys. 2024, 75, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y.C.; Keh, H.J. Transient Electrophoresis of a Charged Porous Particle. Electrophoresis 2020, 41, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, S.; Neale, G.H. The Prediction of Electrokinetic Phenomena within Multiparticle Systems I. Electrophoresis and Electroosmosis. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1974, 47, 520–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zharkikh, N.I.; Shilov, V.N. Theory of Collective Electrophoresis of Spherical Particles in the Henry Approximation. Colloid J. USSR 1982, 43, 865–870. [Google Scholar]

- Carrique, F.; Cuquejo, J.; Arroyo, F.J.; Jimenez, M.L.; Delgado, Á.V. Influence of Cell-Model Boundary Conditions on the Conductivity and Electrophoretic Mobility of Concentrated Suspensions. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2005, 118, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zholkovskij, E.K.; Masliyah, J.H.; Shilov, V.N.; Bhattacharjee, S. Electrokinetic Phenomena in Concentrated Disperse Systems: General Problem Formulation and Spherical Cell Approach. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2007, 134–135, 279–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keh, H.J.; Liu, C.P. Electric Conductivity and Electrophoretic Mobility in Suspensions of Charged Porous Spheres. J. Phys. Chem. C 2010, 114, 22044–22054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, E.I. Time-varying Brinkman Electrophoresis of a Charged Cylinder-in-Cell Model. Eur. J. Mech. B Fluids 2020, 79, 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, N.P.; Berg, J.C. Experiments on the Electrophoresis of Porous Aggregates. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1993, 159, 253–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, C.C.; Keh, H.J. Startup of Electrophoresis in a Suspension of Colloidal Spheres. Electrophoresis 2015, 36, 3002–3008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y.C.; Keh, H.J. Transient Electrophoresis in a Suspension of Charged Particles with Arbitrary Electric Double Layers. Electrophoresis 2021, 42, 2126–2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohshima, H. Transient Electrophoresis of Spherical Colloidal Particles in a Multi-particle Suspension. Colloid Polym. Sci. 2024, 302, 1407–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.W.; Keh, H.J. Transient Slow Motion of a Porous Sphere. Fluid Dyn. Res. 2024, 56, 015503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.Y.; Keh, H.J. Diffusiophoresis in Suspensions of Charged Porous Particles. J. Phys. Chem. B 2015, 119, 2040–2050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talbot, A. The Accurate Numerical Inversion of Laplace Transforms. J. Inst. Maths. Applics. 1979, 23, 97–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murli, A.; Rizzardi, M. Talbot’s Method for the Laplace Inversion Problem. ACM Trans. Math. Softw. 1990, 16, 158–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Happel, J.; Brenner, H. Low Reynolds Number Hydrodynamics; Nijhoff: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1983. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chen, W.Z.; Keh, H.J. Transient Electrophoresis in Suspensions of Charged Porous Particles. Fluids 2026, 11, 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/fluids11010013

Chen WZ, Keh HJ. Transient Electrophoresis in Suspensions of Charged Porous Particles. Fluids. 2026; 11(1):13. https://doi.org/10.3390/fluids11010013

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Wei Z., and Huan J. Keh. 2026. "Transient Electrophoresis in Suspensions of Charged Porous Particles" Fluids 11, no. 1: 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/fluids11010013

APA StyleChen, W. Z., & Keh, H. J. (2026). Transient Electrophoresis in Suspensions of Charged Porous Particles. Fluids, 11(1), 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/fluids11010013