Transient Simulation and Analysis of Runaway Conditions in Pumped Storage Power Station Turbines Using 1D–3D Coupling

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Methods and Numerical Simulation Preprocessing

2.1. Theoretical Method

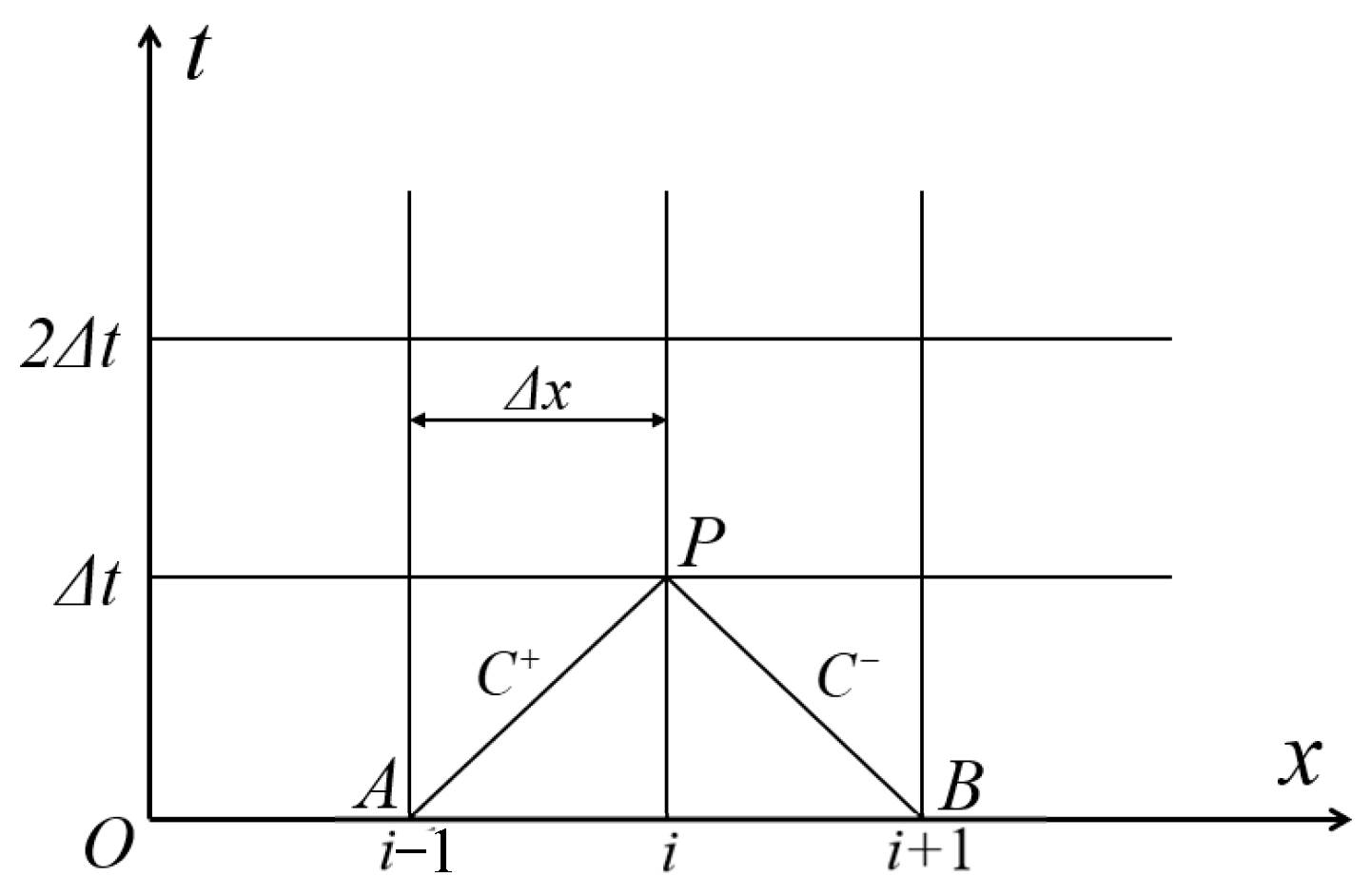

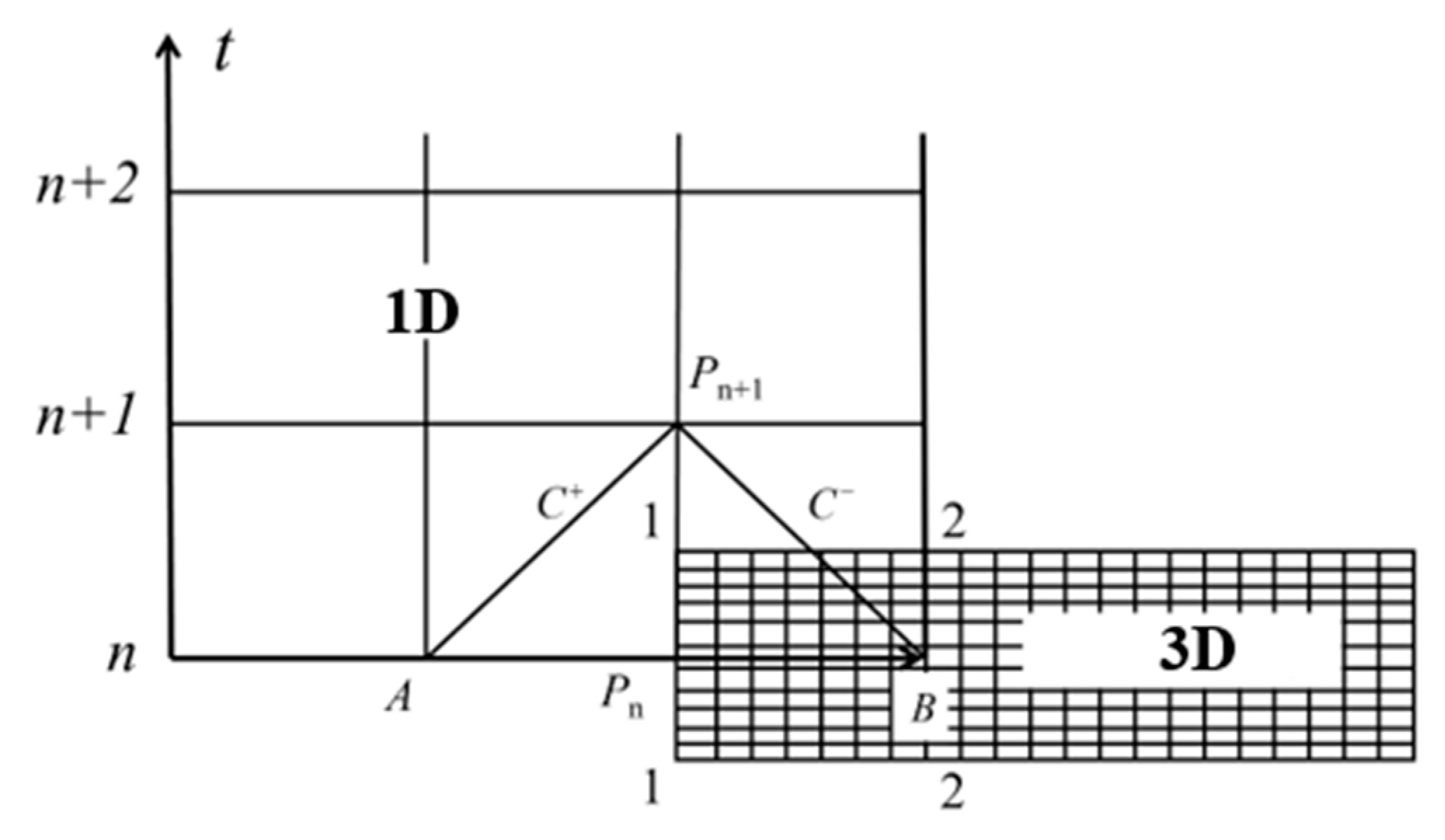

2.1.1. One-Dimensional Characteristic Line Method

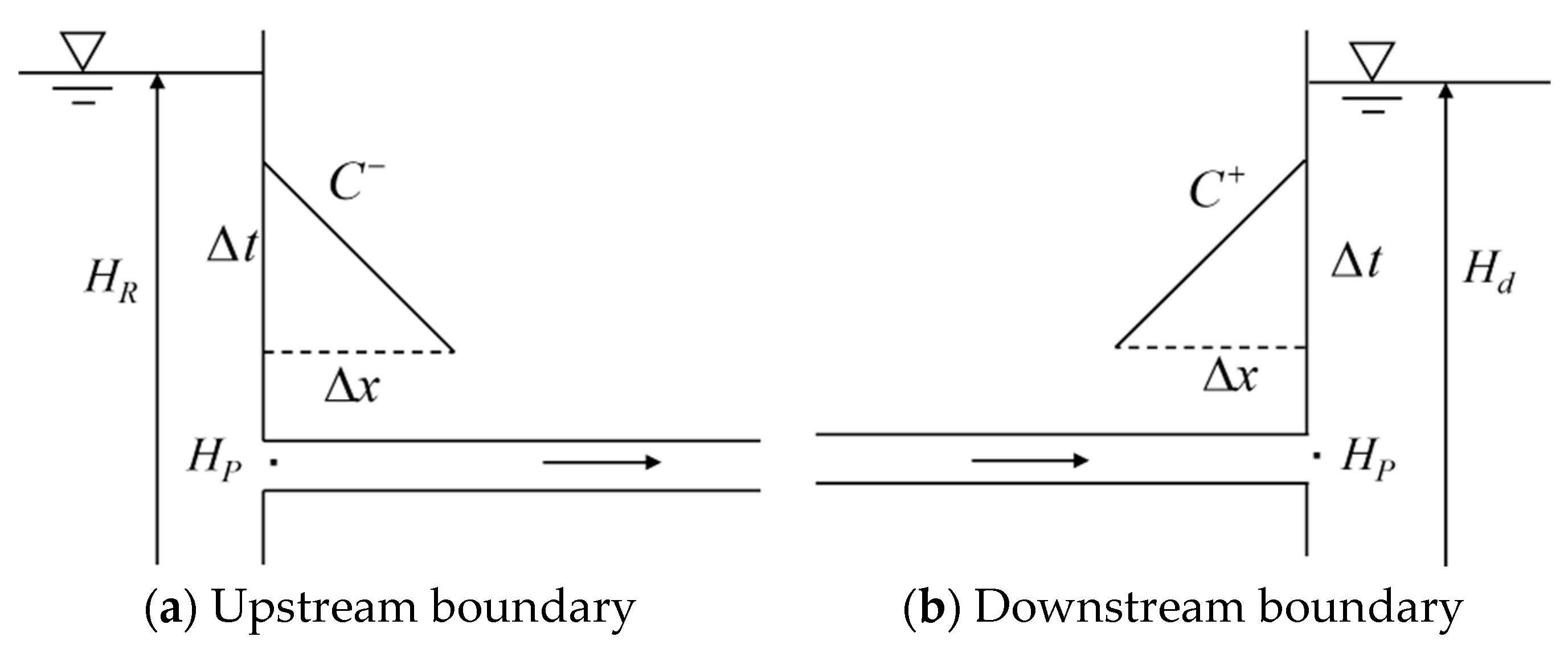

2.1.2. Boundary Condition Theory

Upstream/Downstream Reservoirs

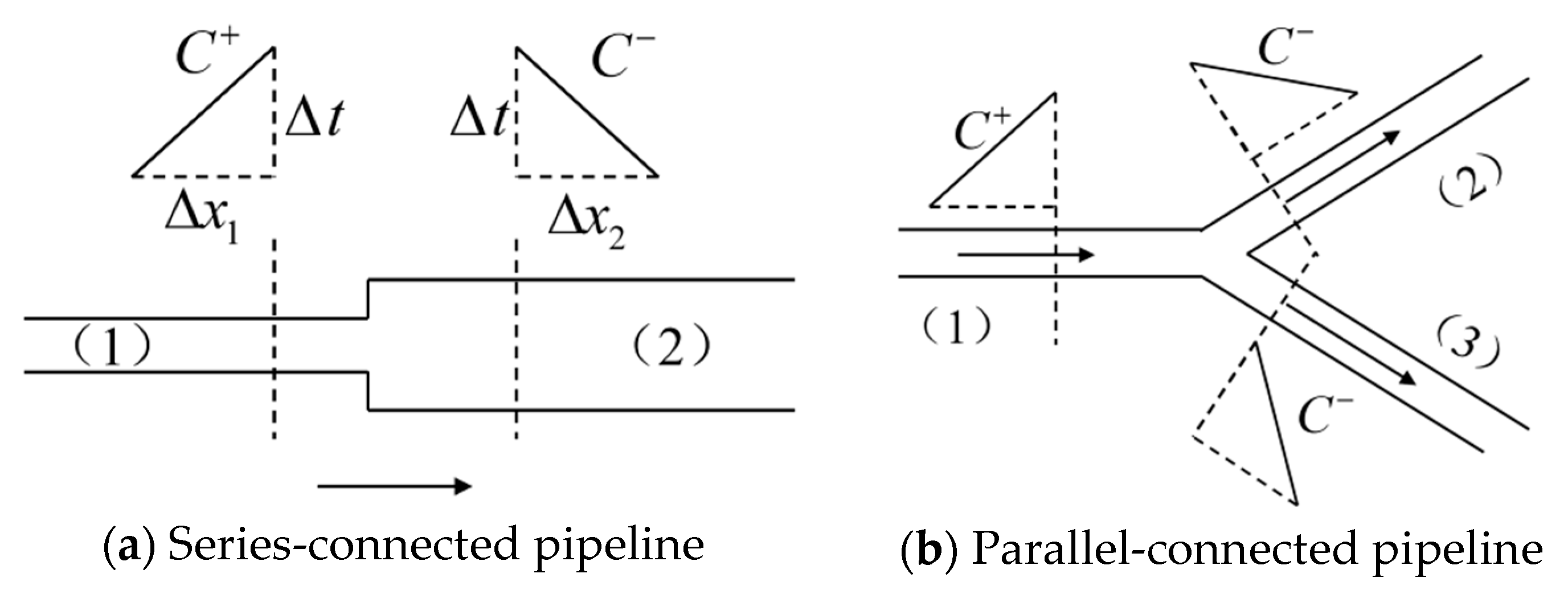

Series/Parallel Pipe Junctions

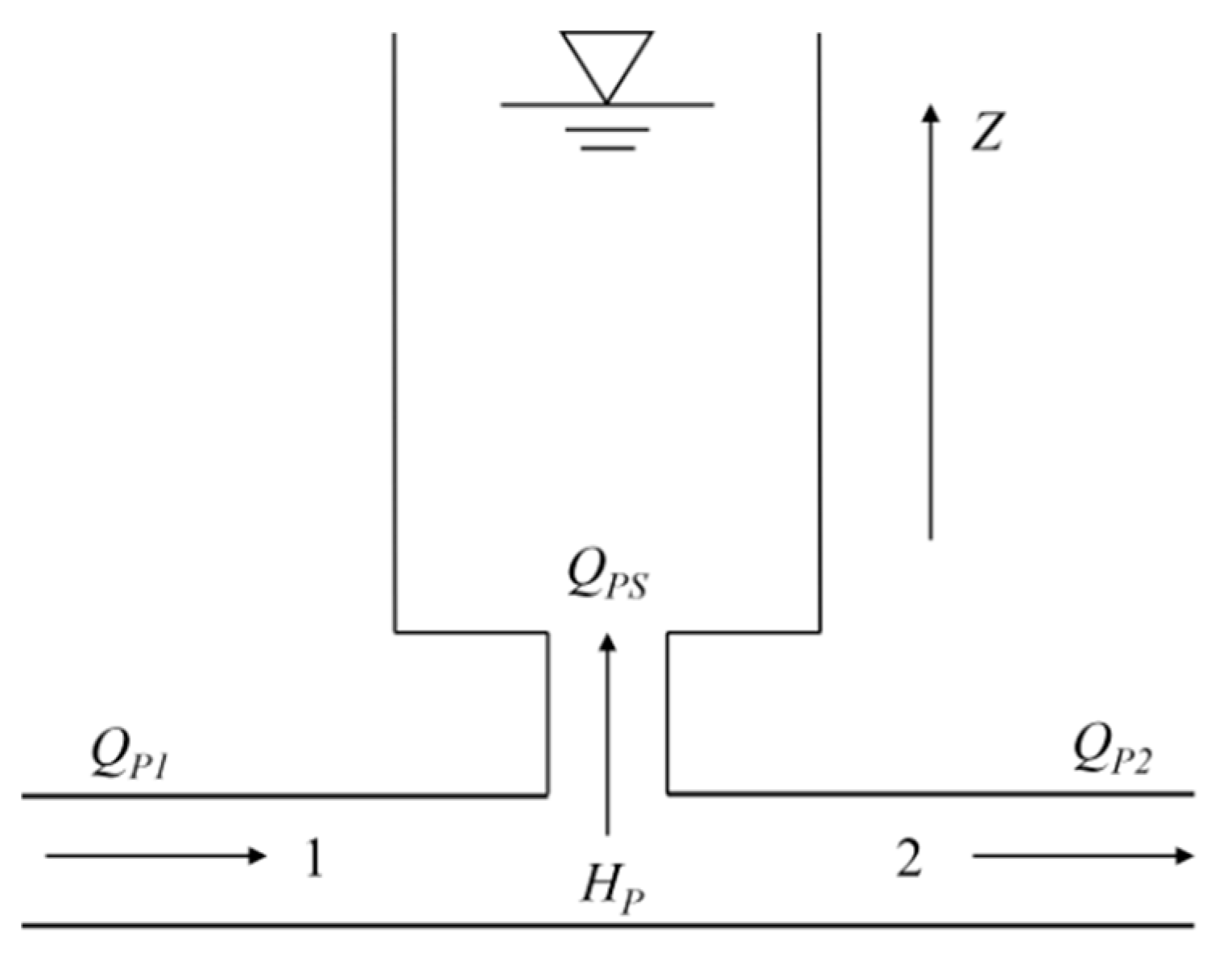

Surge Tank Boundary

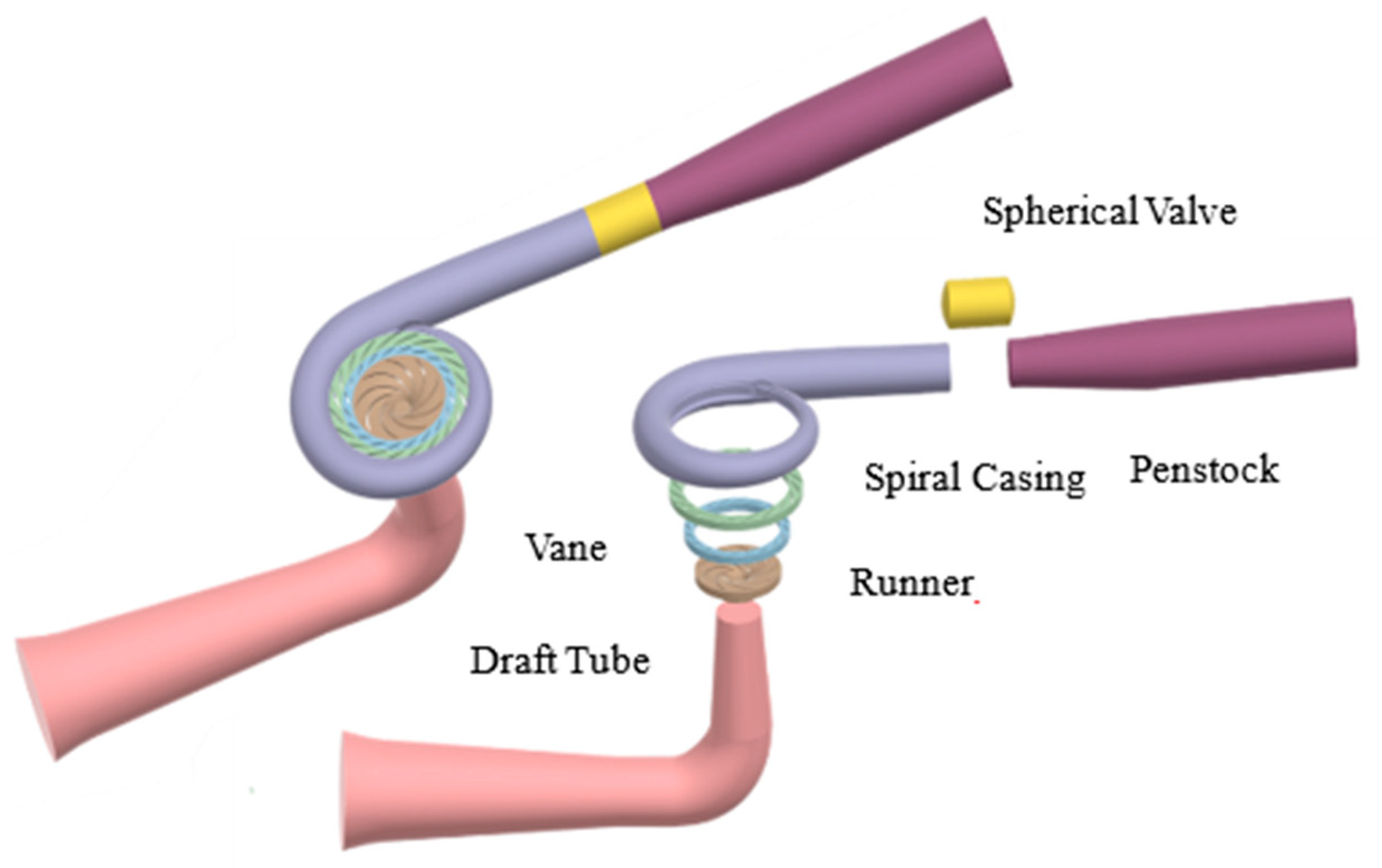

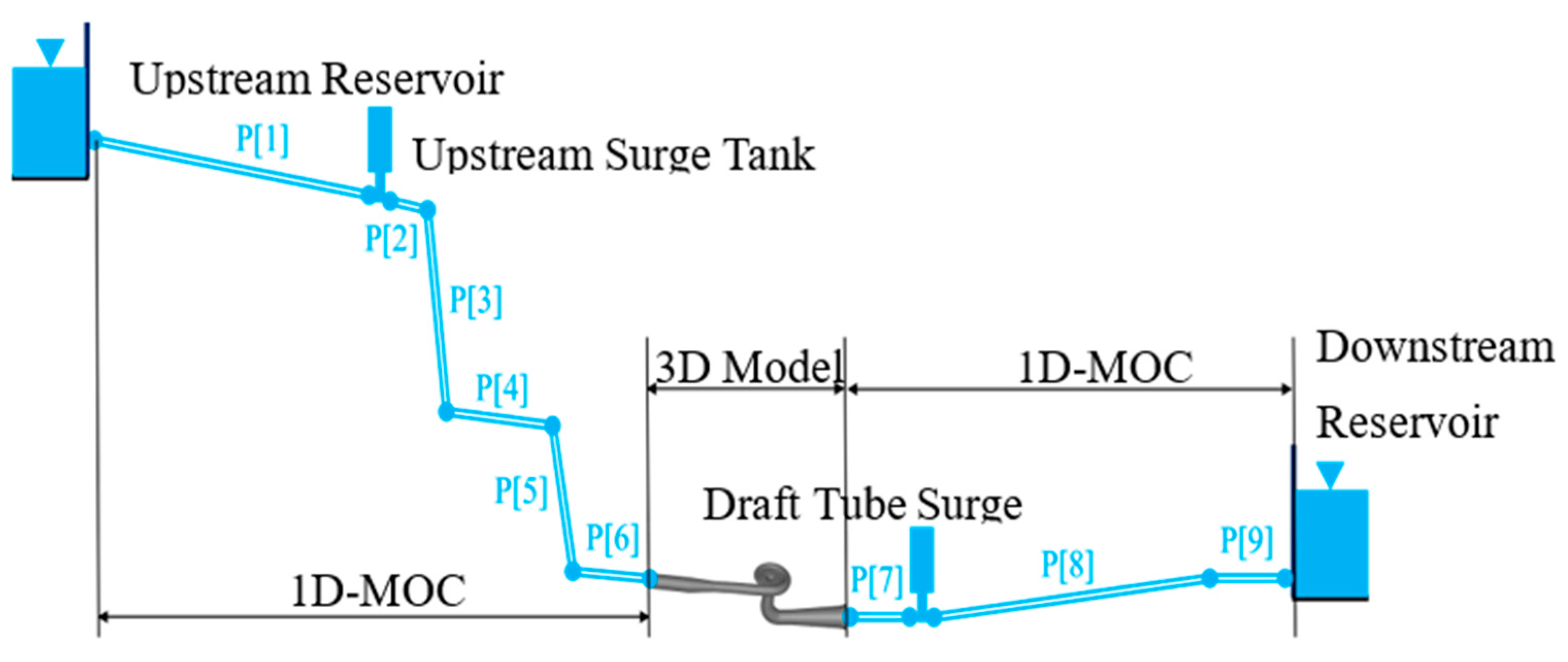

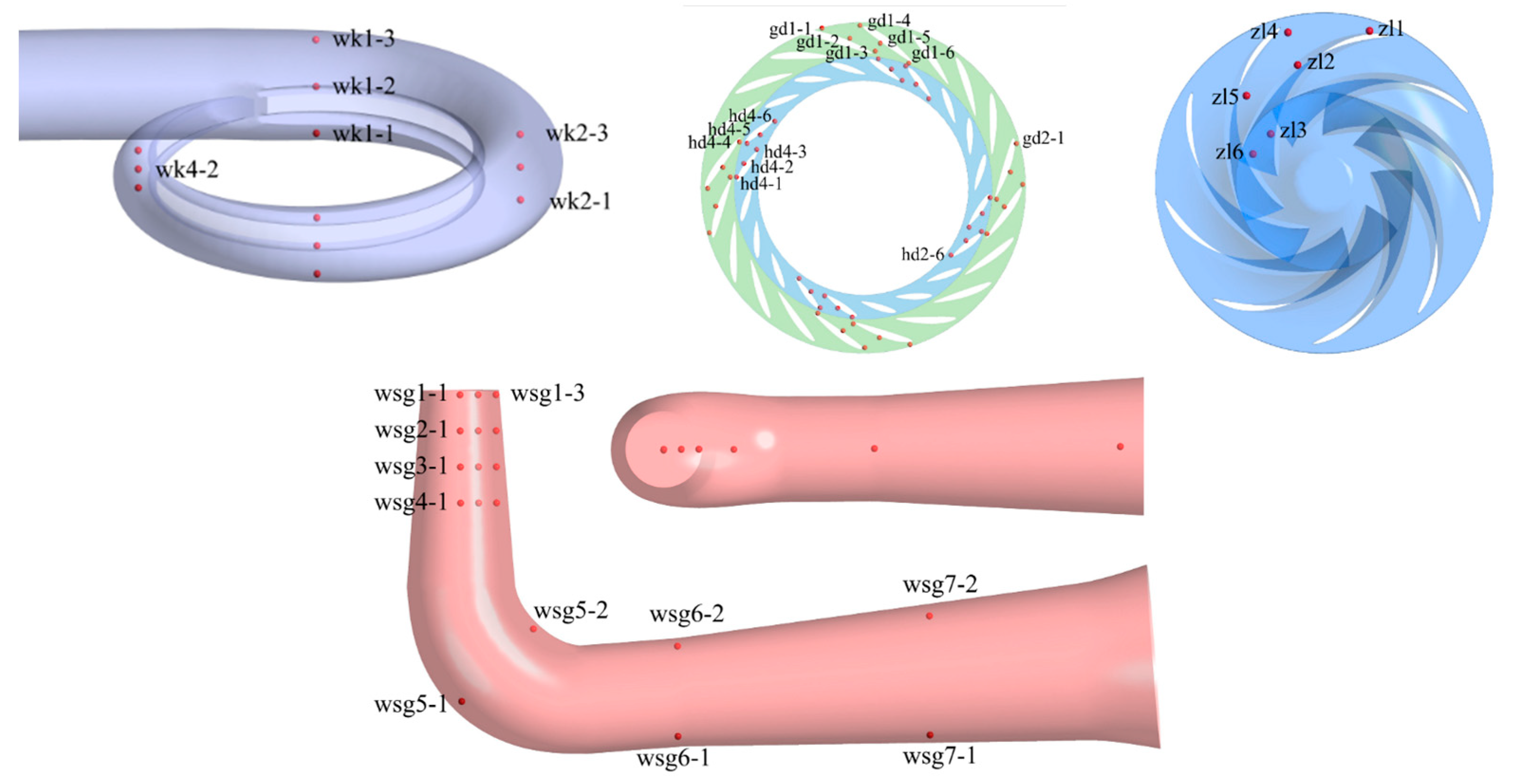

2.2. Model and Mesh Establishment

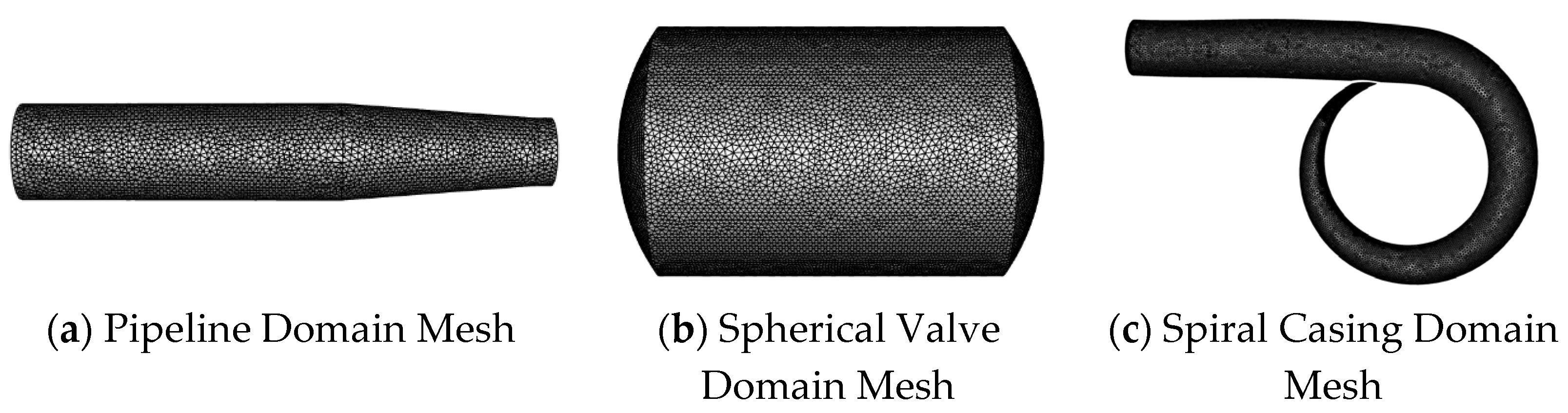

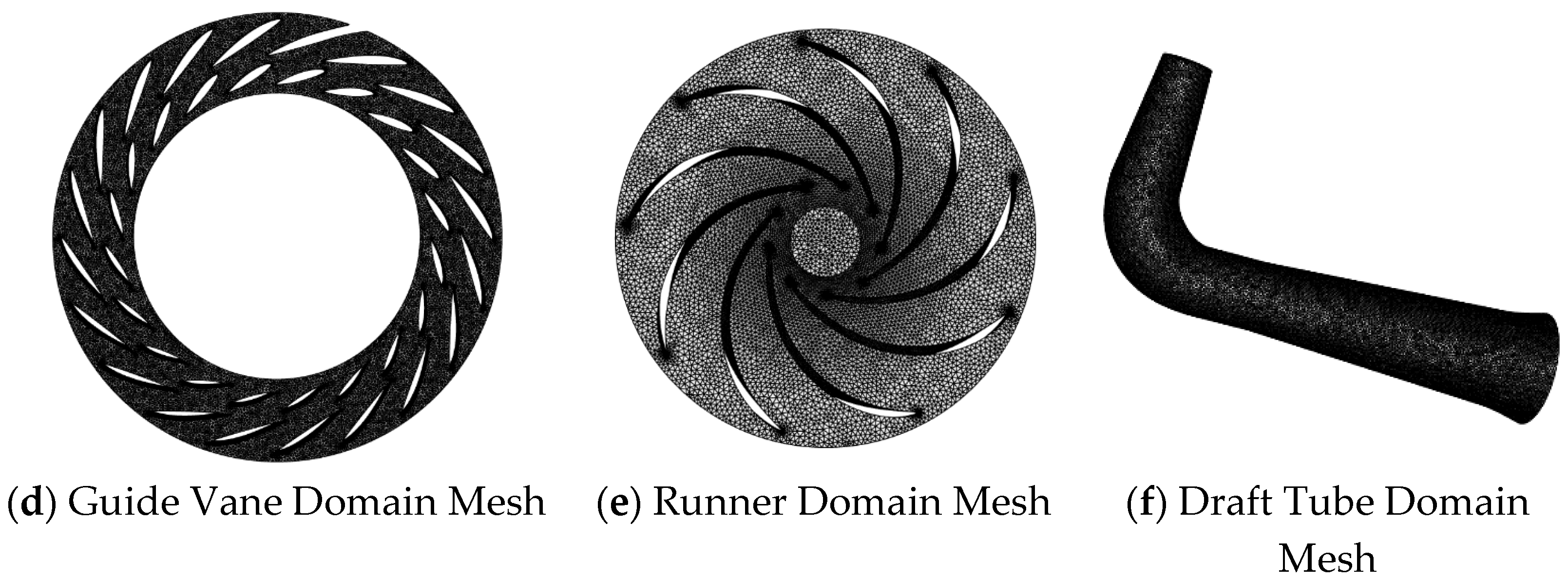

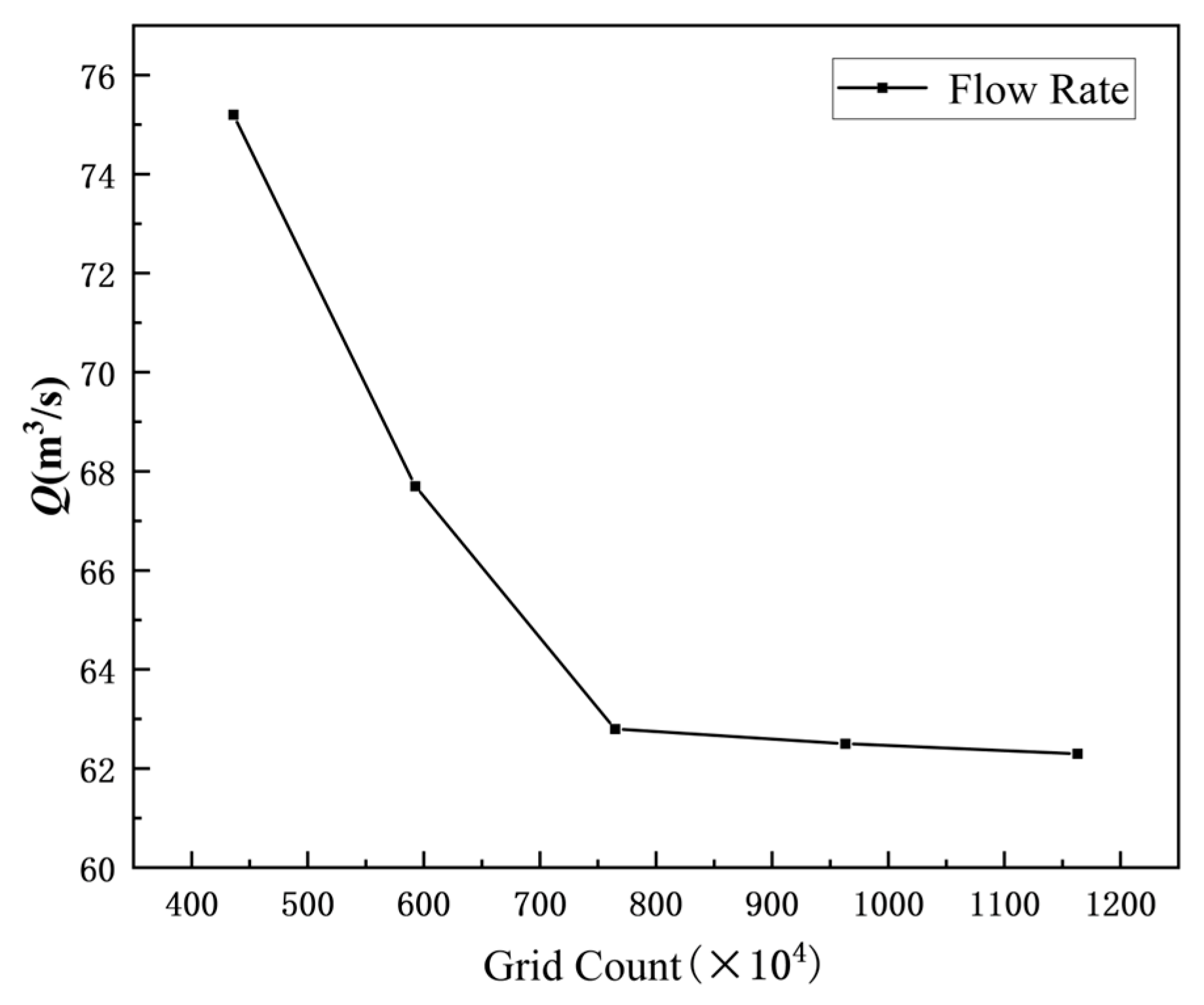

2.3. Grid Generation and Independence Verification

2.4. 1D–3D Coupling Scheme

2.5. Setting of Boundary Conditions

3. Numerical Investigation of the Transient Response During Turbine Runaway

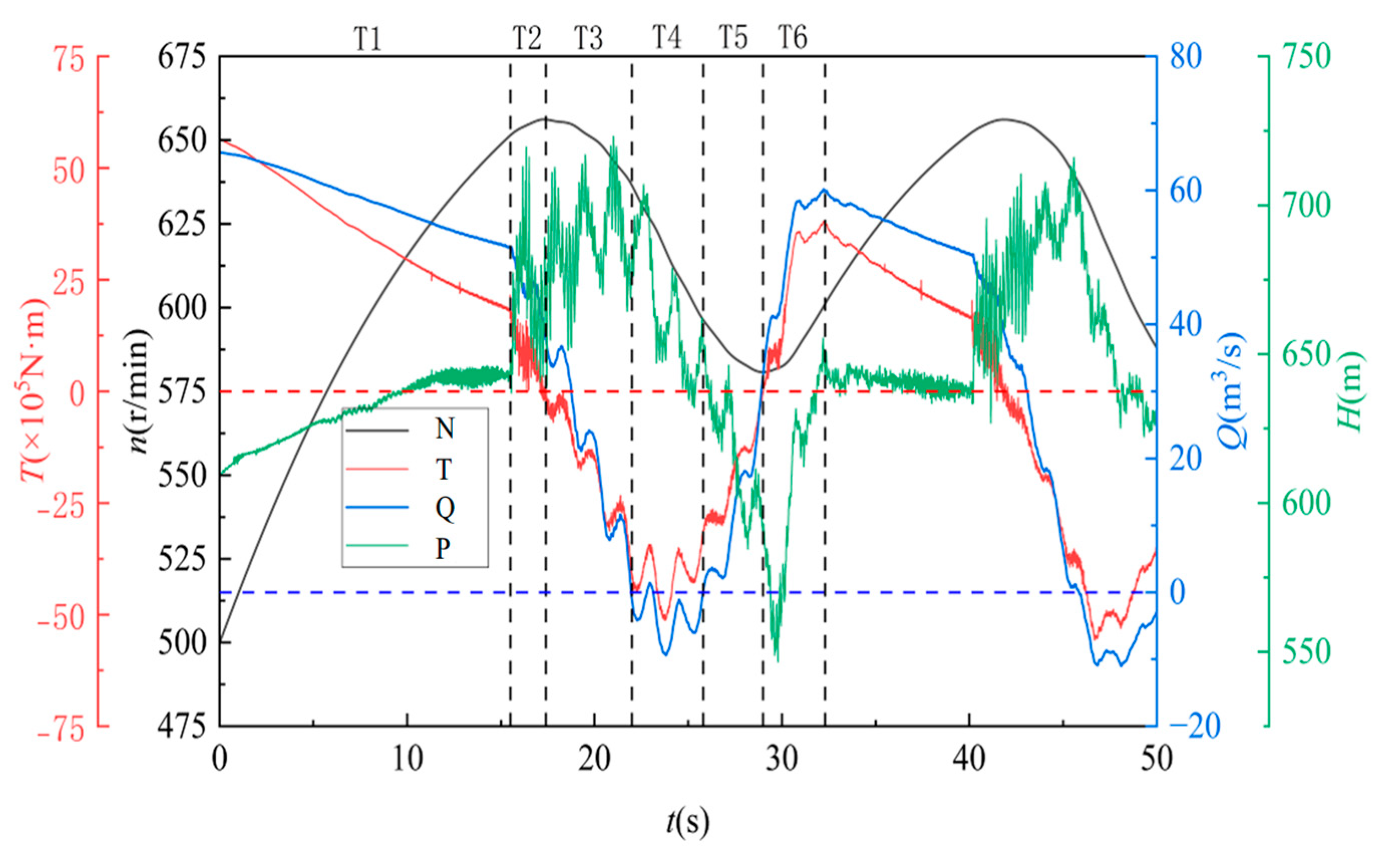

3.1. Analysis of Turbine Runaway External Characteristics

3.2. Analysis of Pressure Pulsation Characteristics in Turbine Runaway Conditions

3.2.1. Time-Domain Characteristic Analysis

3.2.2. Frequency-Domain Characteristic Analysis

3.3. Internal Flow Field Characteristic Analysis of Turbines Under Runaway Conditions

3.3.1. Internal Flow Characteristics of Double-Row Cascades and Runners

3.3.2. Internal Flow Characteristics in Draft Tubes

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- Runaway simulation reveals distinct transitional phases, yielding a predicted runaway speed of 656.16 r/min (0.58% deviation from actual value) and peak pressure of 722.96 m. Attenuated water hammer pressure reduces the periodic oscillation amplitudes during subsequent entries into the inverse S-shaped region.

- (2)

- The Short-Time Fourier Transform (STFT) analysis identifies the following: high-frequency pulsations at 1×/2× blade passing frequency (runner-induced rotor–stator interference), prevalent throughout the flow passage; broad-spectrum high-amplitude pulsations during operational mode transitions, concentrated near torque turning points; low-frequency high-amplitude pulsations at 1×/2× runner frequency (draft tube vortex ropes), primarily affecting the draft tube domain.

- (3)

- At 650.9 r/min, large-scale vortices (>500 s−1) obstruct selected runner blade passages, while draft tube vortex ropes transition from central helical structures to wall-attached configurations. Their synergistic effect triggers abrupt runner force variations and intense pressure pulsations.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xie, Z.; Wang, Y.; Chang, J.; Guo, A.; Niu, C.; Zheng, Y.; Tian, Z. Optimal scheduling and benefit sharing of hybrid pumped storage hydropower plants with multiple operators. Energy 2025, 333, 137242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Xu, Y. Site Selection Evaluation of Pumped Storage Power Station Based on Multi-Energy Complementary Perspective: A Case Study in China. Energies 2025, 18, 3549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Xu, L.; Wang, D.; Li, D.; Li, W. Simulation analysis of energy characteristics of flow field in the transition process of pump condition outage of pump-turbine. Renew. Renew. Energy 2023, 219, 119480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhry, M.H. Practical Analysis of Hydraulic Transients; China Water&Power Press: Beijing, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolet, C.; Alligne, S.; Kawkabani, B.; Simond, J.-J.; Avellan, F. Unstable Operation of Francis Pump-Turbine at Runaway: Rigid and Elastic Water Column Oscillation Modes. Int. J. Fluid Mach. Syst. 2009, 2, 324–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadian, A.; Le Roux, D.Y.; Tajrishi, M. A conservative extension of the method of characteristics for 1-D shallow flows. Appl. Math. Model. 2007, 31, 332–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Wang, X.; Zheng, X.; Chen, X.; Meng, S.; Ruan, T.; Chen, J.; Mao, Y.; Hu, Y.; Shang, C. Development and preliminary verification of a 1D–3D coupled flow and heat transfer model of OTSG. Front. Energy Res. 2024, 12, 1368303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Yin, X.; Wang, W.; Huang, X.; Zhang, S.; Bi, H.; Wang, Z. Flow-induced vibration analysis of a prototype pump-turbine runner during turbine start-stop transient process. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2022, 1079, 012073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Che, J.; Chen, S. One-dimensional and three-dimensional coupling simulation research of centrifugal cascade hydraulics. Kerntechnik 2022, 87, 176–186. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Jiang, Z.; Chen, S.; Zhang, W.; Zhu, B. Experimental and numerical study on flow instability of pump-turbine under runaway conditions. Renew. Energy 2023, 210, 335–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, C.; Cervantes, M.J.; Gandhi, B.K. Investigation of a High Head Francis Turbine at Runaway Operating Conditions. Energies 2016, 9, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Li, Q.; Xin, L. Analysis of Vortex Evolution in the Runner Area of Water Pump Turbine Under Runaway Conditions. Processes 2023, 11, 2080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Guo, P.; Cao, M.; Sun, L. Investigation into the Energy Loss Mechanism of Pump Turbine During the Runaway Process Based on Entropy Production Theory. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2024, 2854, 012047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, W.; Gui, Z.; Lu, Z.; Xiao, R.; Tao, R. Pressure pulsation of pump turbine at runaway condition based on Hilbert Huang transform. Front. Energy Res. 2024, 12, 1344676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Li, Q.; Chen, X.; Li, Z.; Li, S. A Study on the Transient Flow Characteristics of Pump Turbines Across the Full Operating Range in Turbine Mode. Energies 2025, 18, 3517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Li, W.; Luo, X.; Zhu, G. Numerical analysis of transient characteristics of a bulb hydraulic turbine during runaway transient process. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part E J. Process Mech. Eng. 2019, 233, 813–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezghi, A.; Riasi, A. Sensitivity analysis of transient flow of two parallel pump-turbines operating at runaway. Renew. Energy 2016, 86, 611–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Fu, X.; Li, D.; Lv, J.; Wang, H.; Wei, X. Instability flow mechanism of ultra-high head pumped-storage units during turbine runaway process. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2024, 71, 104028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Li, D.; Wang, H.; Zhang, G.; Wei, X. Cavitation mechanism in turbine runaway process of a pump-turbine. J. Hydraul. Res. 2022, 60, 750–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zhou, D.; Liu, D.; Wu, Y.; Nishi, M. Runaway transient simulation of a model Kaplan turbine. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2010, 12, 012073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Chen, Q.; Liao, J. Dynamic evolutions between the draft tube pressure pulsations and vortex ropes of a Francis turbine during runaway. Int. J. Fluid Mach. Syst. 2017, 10, 404–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guang, W.; Liu, Q.; Tao, R.; Liang, Q.; Xiao, R. Research on the influence of labyrinth ring configuration on runaway characteristics of pump-turbines. J. Energy Storage 2024, 101, 113945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Lv, J.; Li, D.; Wang, H.; Qin, D.; Wei, X. Suppression mechanism of transient pressure during the turbine runaway of an ultra-high head pump-turbine. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2024, 2752, 012057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, L.; Yongguang, C.; Jinghuan, D.; Xi, W. Evolution of Runner Forces During Simultaneous Pump-Trip Transient Process of Two Pump-Turbines. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2024, 2752, 012061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.; Yan, W.; Guang, W.; Wang, Z.; Tao, R. Influence of Guide Vane Opening on the Runaway Stability of a Pump-Turbine Used for Hydropower and Ocean Power. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galindo, J.; Tiseira, A.; Fajardo, P.; Navarro, R. Coupling methodology of 1D finite difference and 3D finite volume CFD codes based on the Method of Characteristics. Math. Comput. Model. 2010, 54, 1738–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.-X.; Cheng, Y.-G. Simulation of Hydraulic Transients in Hydropower Systems Using the 1-D-3-D Coupling Approach. J. Hydrodyn. 2012, 24, 595–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Chen, D.; Wu, C.; Wang, X.; Lee, J.-M.; Jung, K.-H. Dynamic modeling and dynamical analysis of pump-turbines in S-shaped regions during runaway operation. Energy Convers. Manag. 2017, 138, 375–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Basic Parameters | Symbol | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Number of runner blades | Zr | 9 |

| Number of guide vanes | Zg | 20 |

| Number of stay vanes | Zs | 20 |

| Rated head | Hr | 540 m |

| Rotational speed | Nr | 500 r/min |

| Runaway speed | n11r | 660 r/min |

| Rated power | Pr | 306 MW |

| Pipe ID | Friction Loss Coefficient hw | Pipe Diameter D (m) | Pipe Length L (m) | Wave Speed a (m/s) | Inlet Elevation Hin (m) | Outlet Elevation Hout (m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P[1] | 0.0115 | 6 | 452.19 | 1100 | 703.2 | 674.42 |

| P[2] | 0.013 | 6 | 56.2 | 1100 | 674.42 | 672.38 |

| P[3] | 0.0115 | 5.2 | 274.3 | 1120 | 672.38 | 398.09 |

| P[4] | 0.012 | 5.2 | 195.92 | 1120 | 398.09 | 394.17 |

| P[5] | 0.0123 | 4.8 | 292.47 | 1120 | 394.17 | 101.69 |

| P[6] | 0.021 | 4.4 | 98.42 | 1120 | 101.69 | 94.3 |

| P[7] | 0.012 | 4.8 | 155.4 | 1120 | 83.3 | 98.6 |

| P[8] | 0.0115 | 6.5 | 999.27 | 1100 | 98.6 | 165.4 |

| P[9] | 0.0119 | 6.5 | 122.63 | 1100 | 165.4 | 165.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Hang, C.; Ding, K.; Du, Y.; Sun, D.; Yang, C. Transient Simulation and Analysis of Runaway Conditions in Pumped Storage Power Station Turbines Using 1D–3D Coupling. Fluids 2025, 10, 318. https://doi.org/10.3390/fluids10120318

Yang X, Zhang Z, Hang C, Ding K, Du Y, Sun D, Yang C. Transient Simulation and Analysis of Runaway Conditions in Pumped Storage Power Station Turbines Using 1D–3D Coupling. Fluids. 2025; 10(12):318. https://doi.org/10.3390/fluids10120318

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Xiaowen, Zhicheng Zhang, Chenyang Hang, Kechengqi Ding, Yuxi Du, Dian Sun, and Chunxia Yang. 2025. "Transient Simulation and Analysis of Runaway Conditions in Pumped Storage Power Station Turbines Using 1D–3D Coupling" Fluids 10, no. 12: 318. https://doi.org/10.3390/fluids10120318

APA StyleYang, X., Zhang, Z., Hang, C., Ding, K., Du, Y., Sun, D., & Yang, C. (2025). Transient Simulation and Analysis of Runaway Conditions in Pumped Storage Power Station Turbines Using 1D–3D Coupling. Fluids, 10(12), 318. https://doi.org/10.3390/fluids10120318