From Surface Energetics to Environmental Functionality: Mechanistic Insights into Hg(II) Removal by L-Cysteine-Modified Silica Gel

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

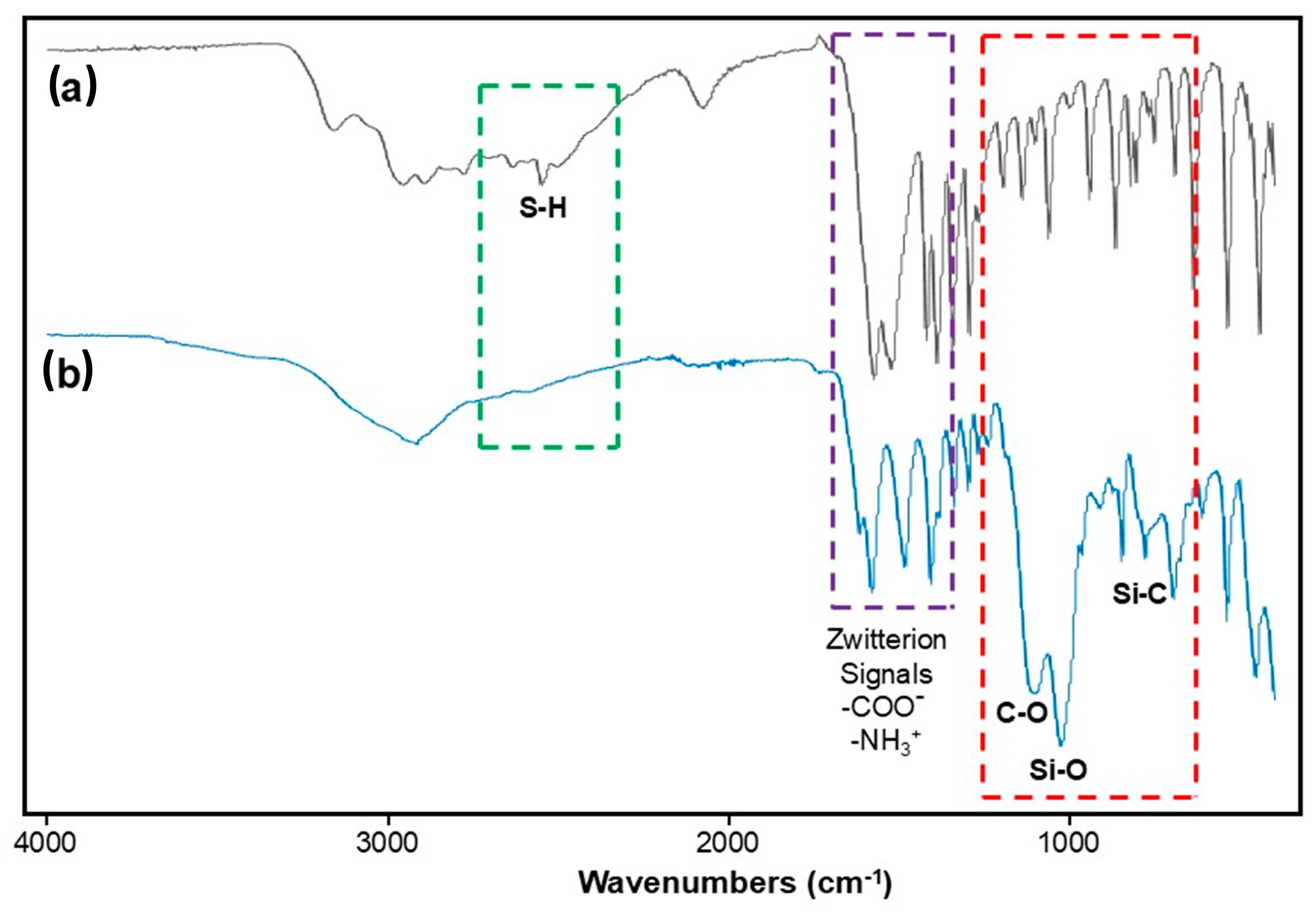

2.1. FTIR Analysis of the Functional Precursor 3PTES-Cys

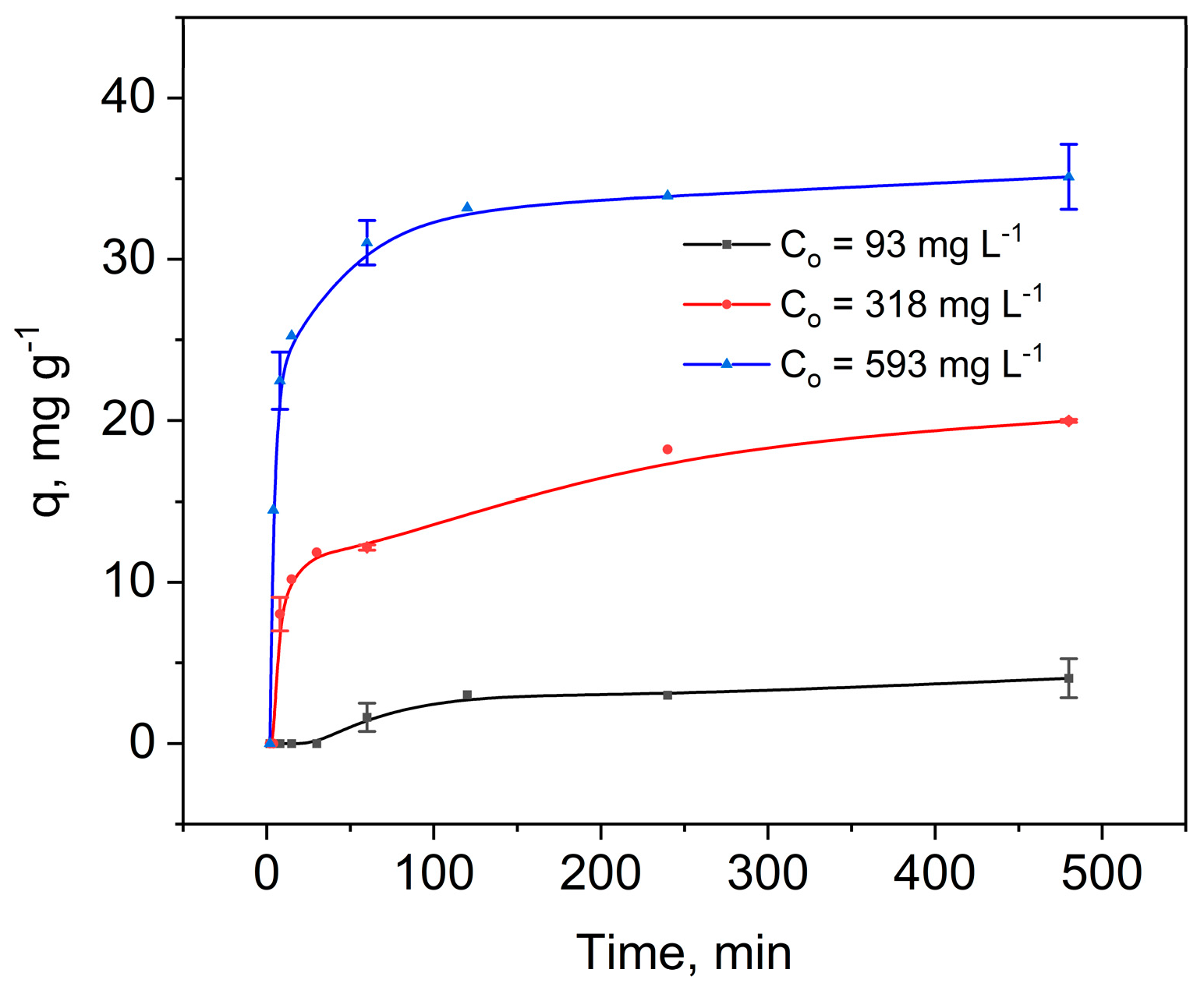

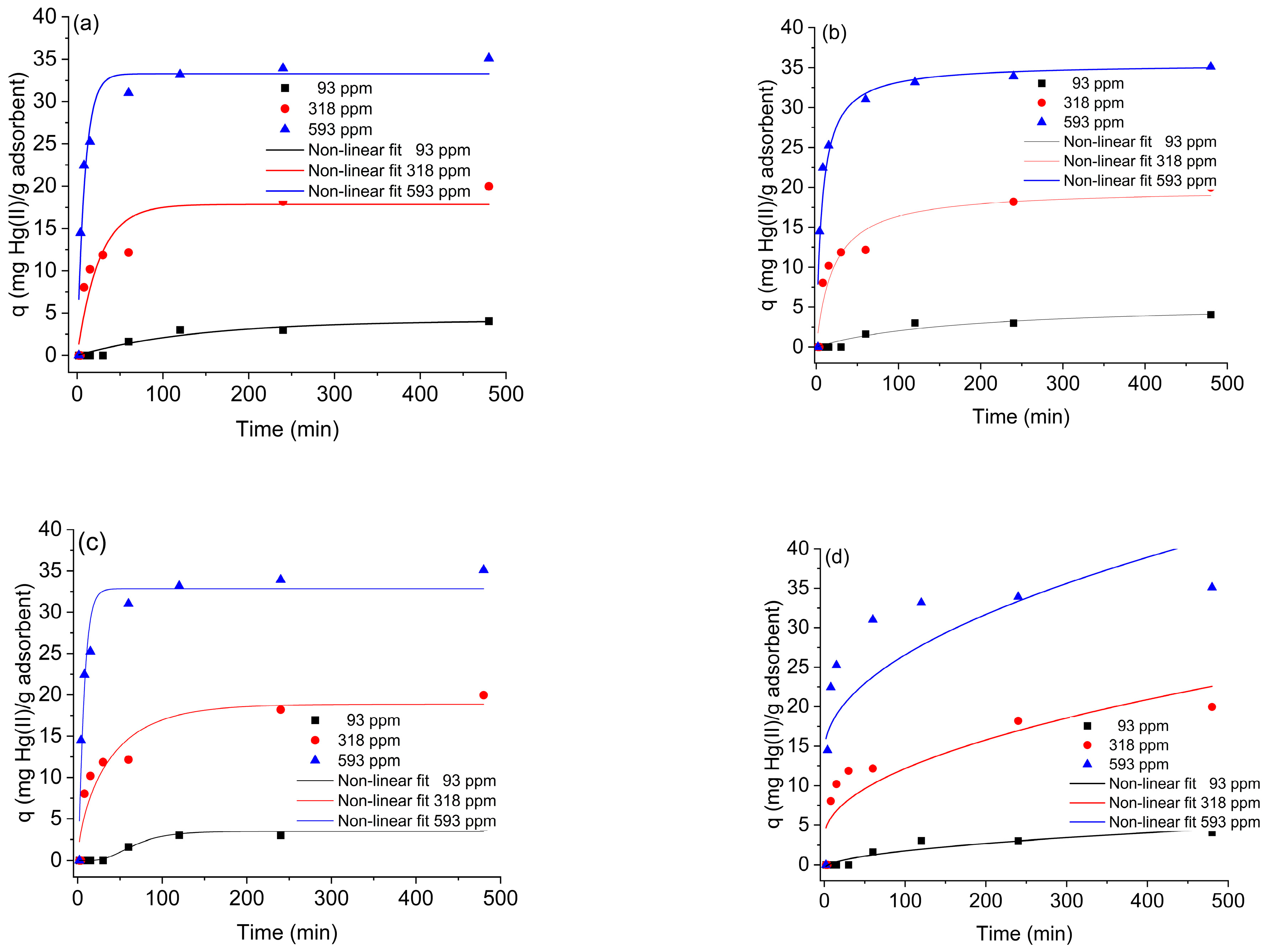

2.2. Hg(II) Adsorption Kinetics on SG-3PS-Cys

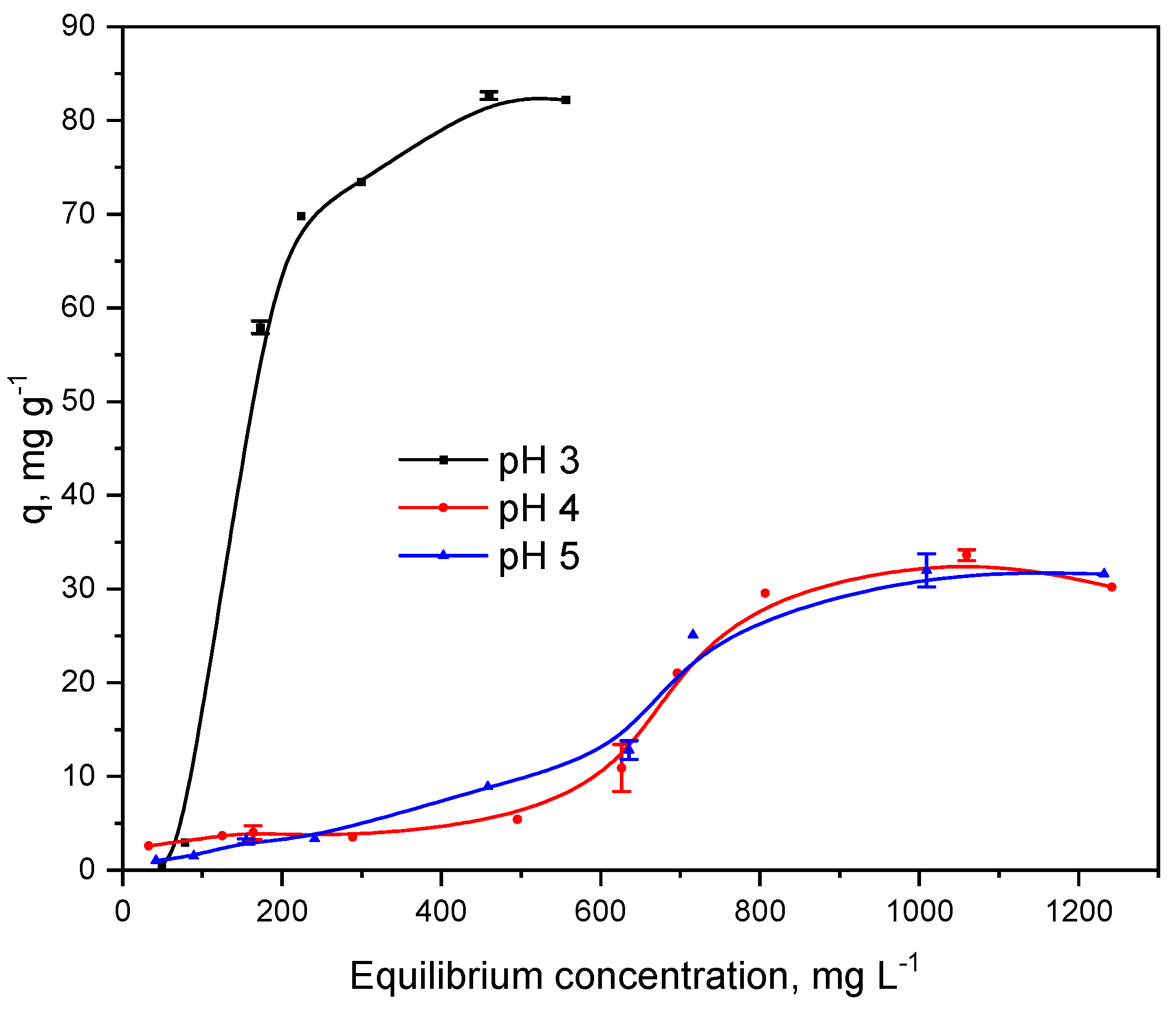

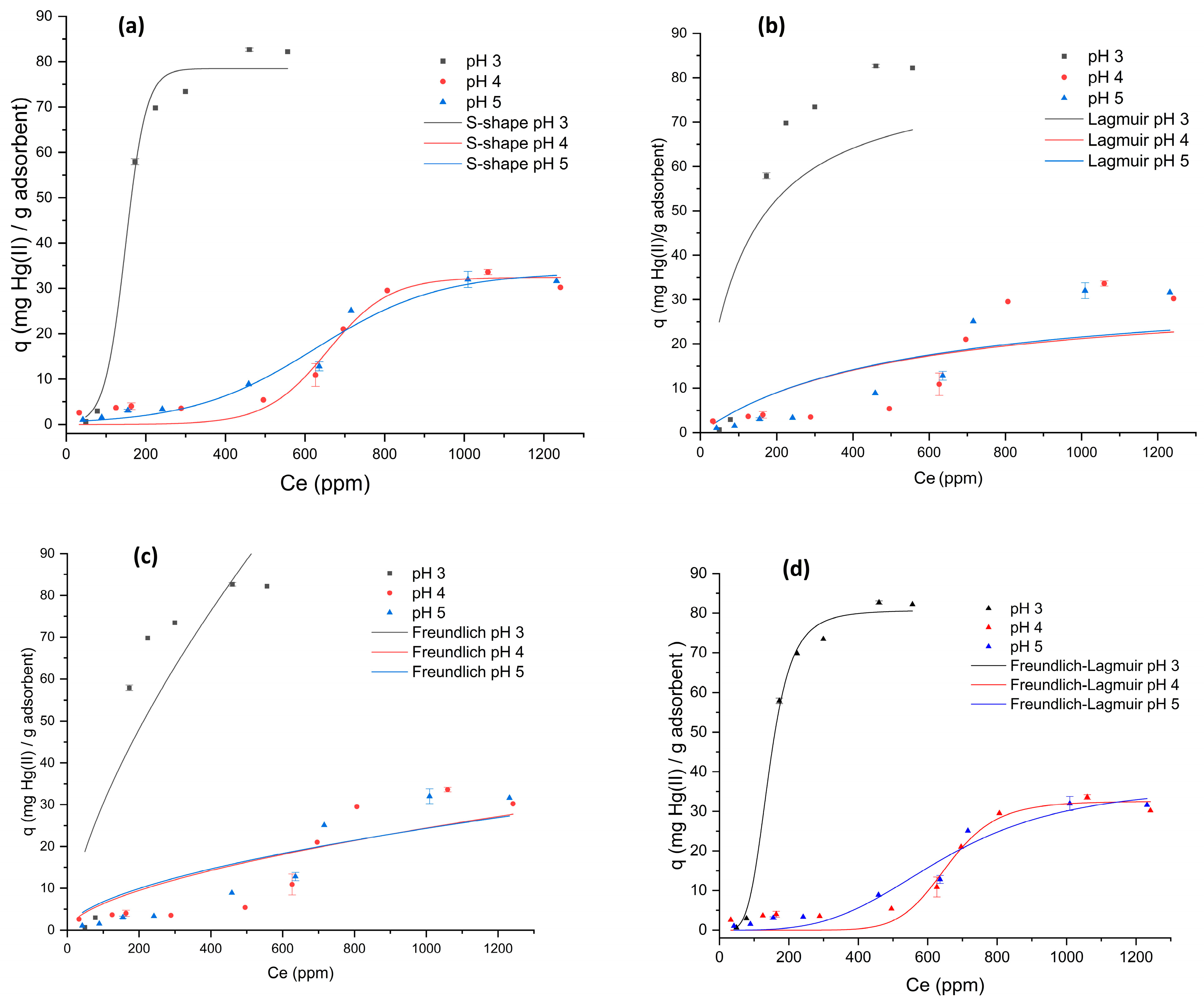

2.3. Equilibrium Adsorption Isotherms

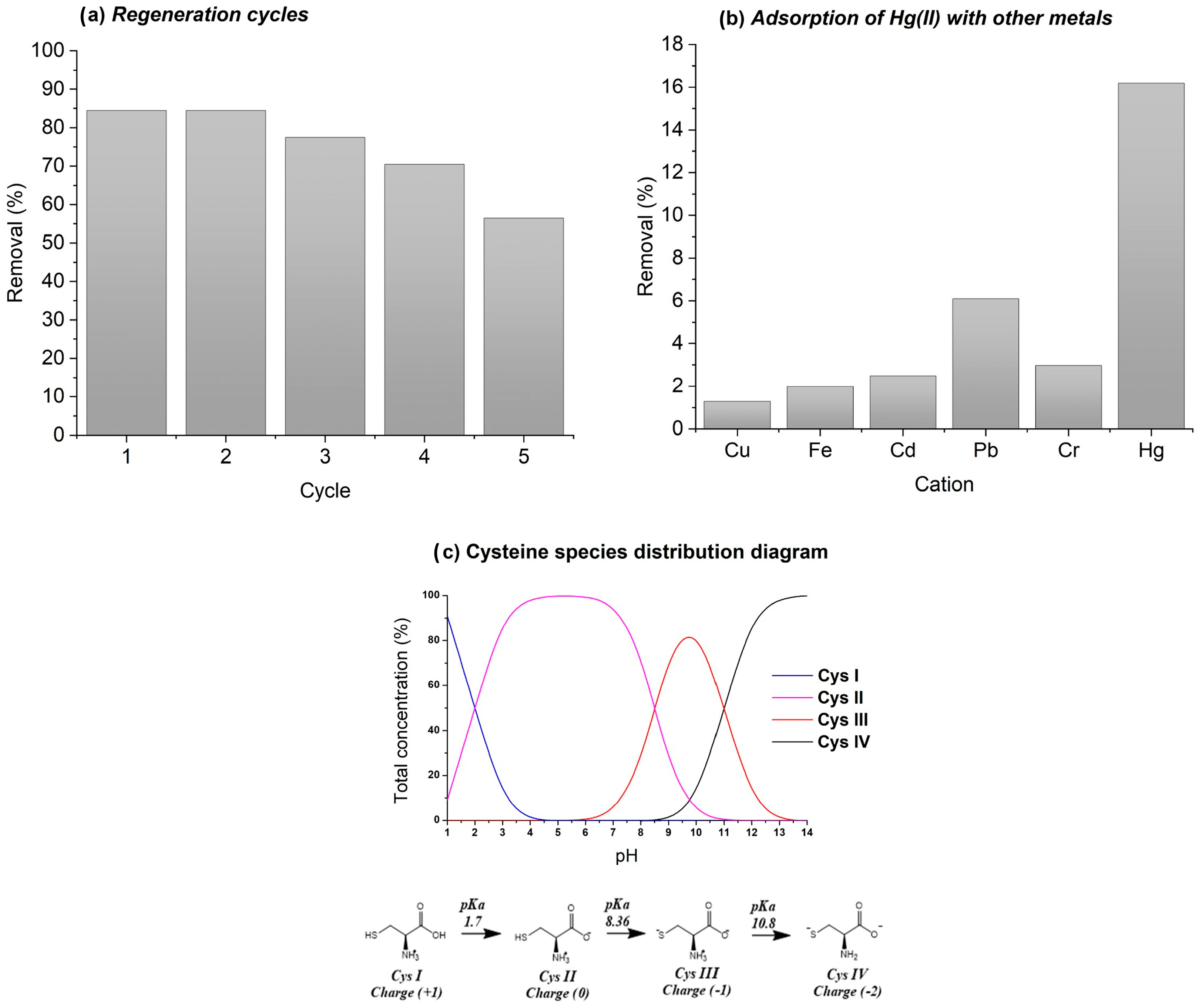

2.4. Regeneration Study and Multi-Cation Analysis

2.5. Comparative Evaluation of Hg(II) Adsorbents

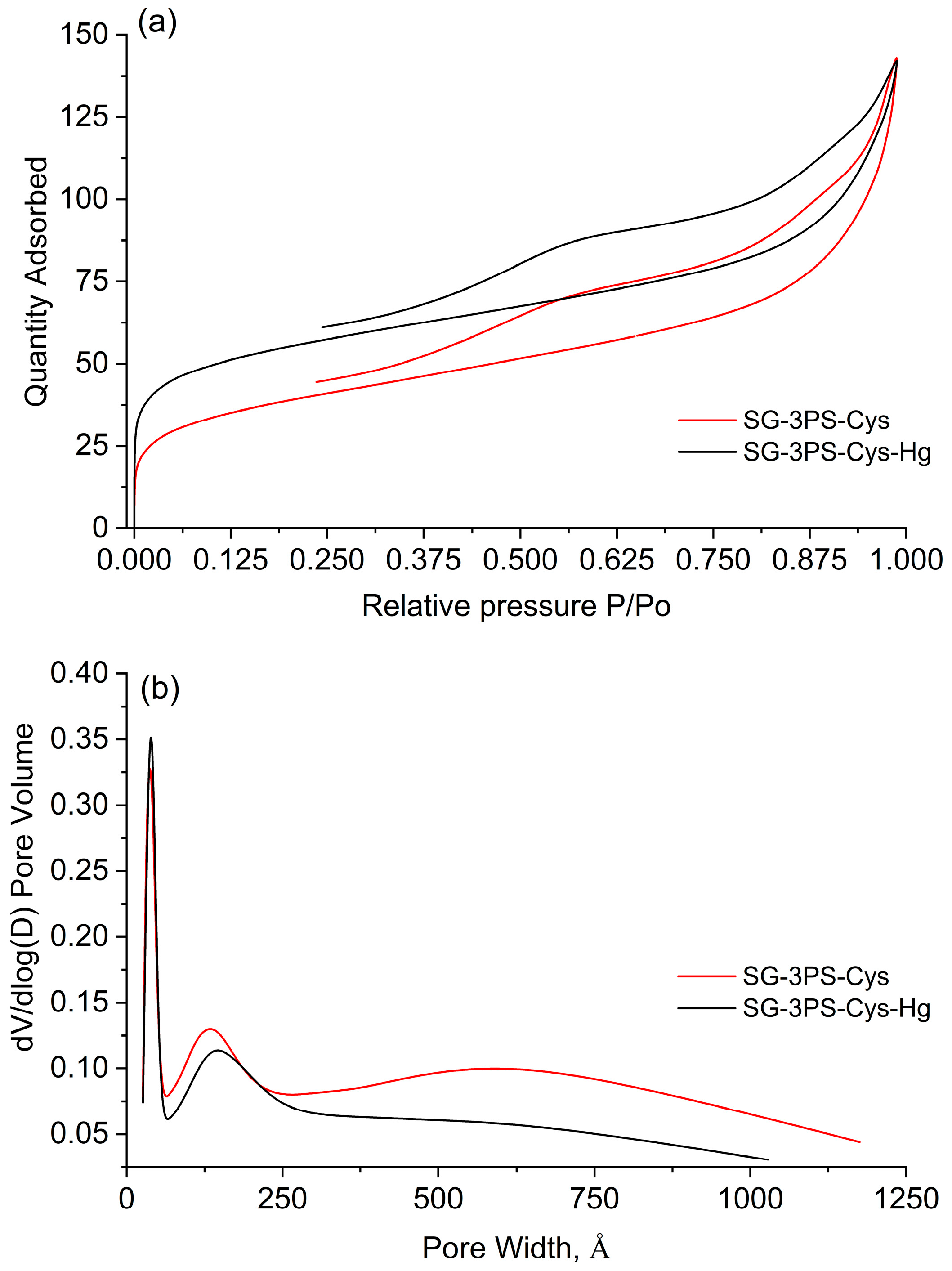

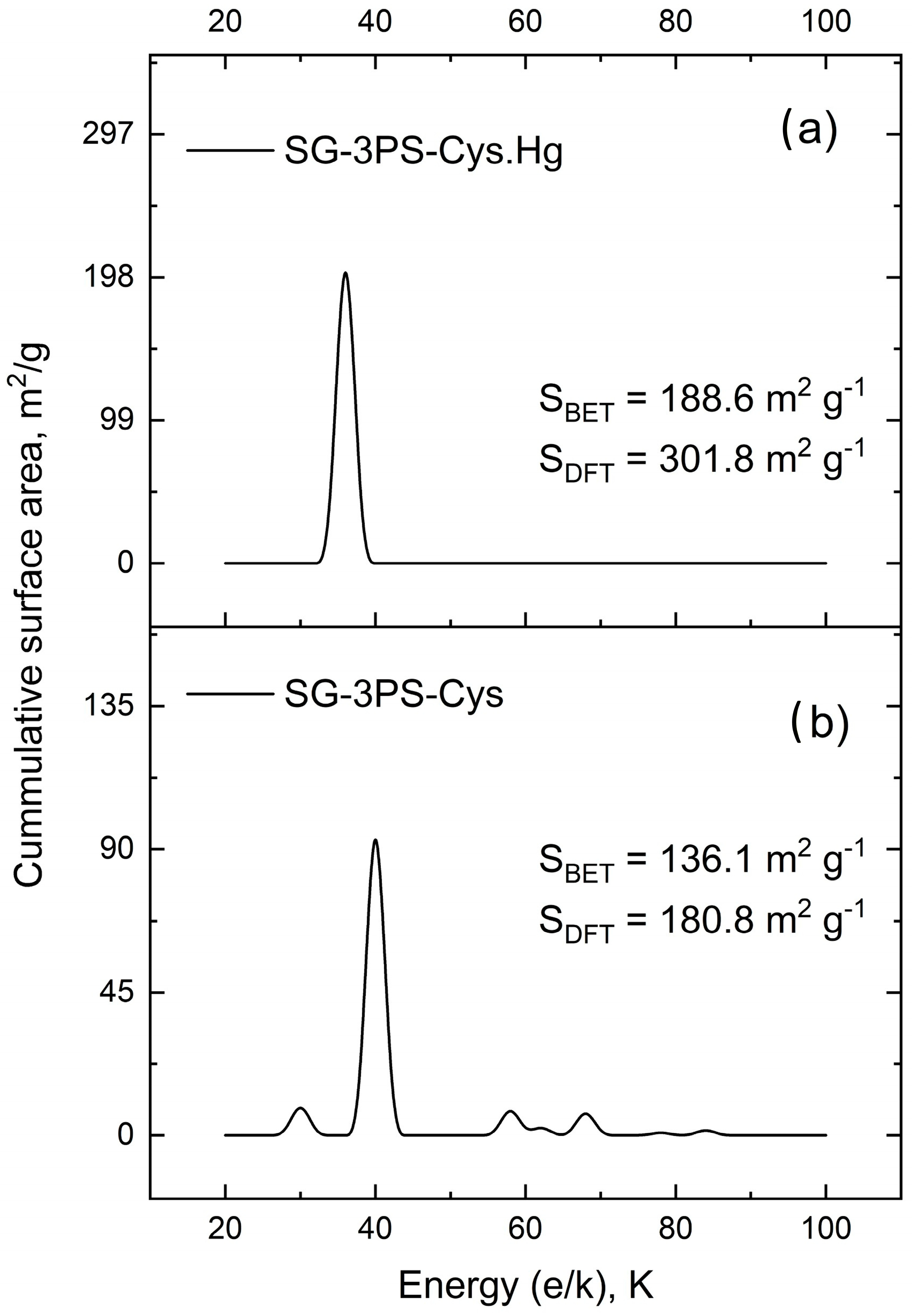

2.6. N2 Adsorption–Desorption Results

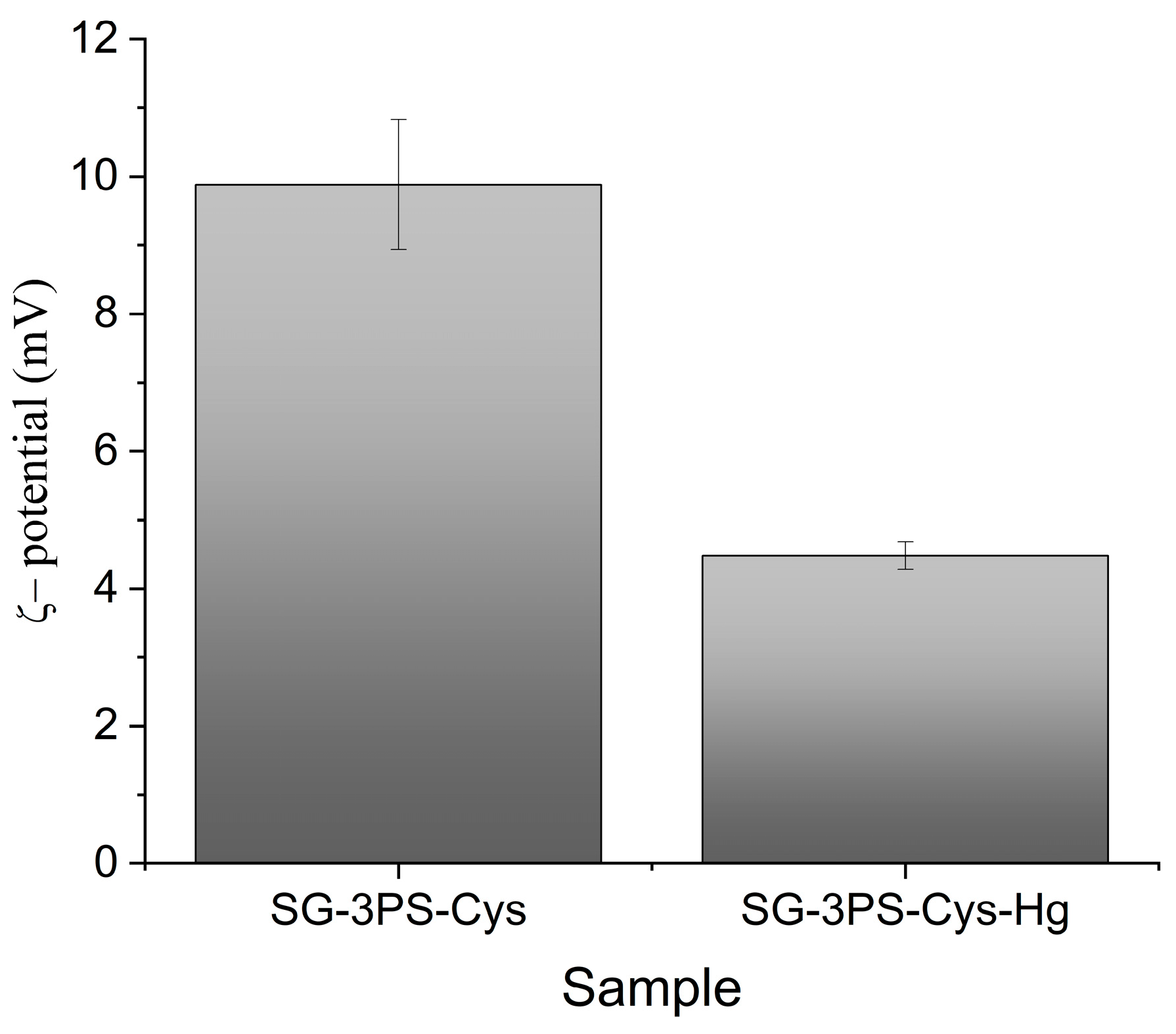

2.7. ζ-Potential Results

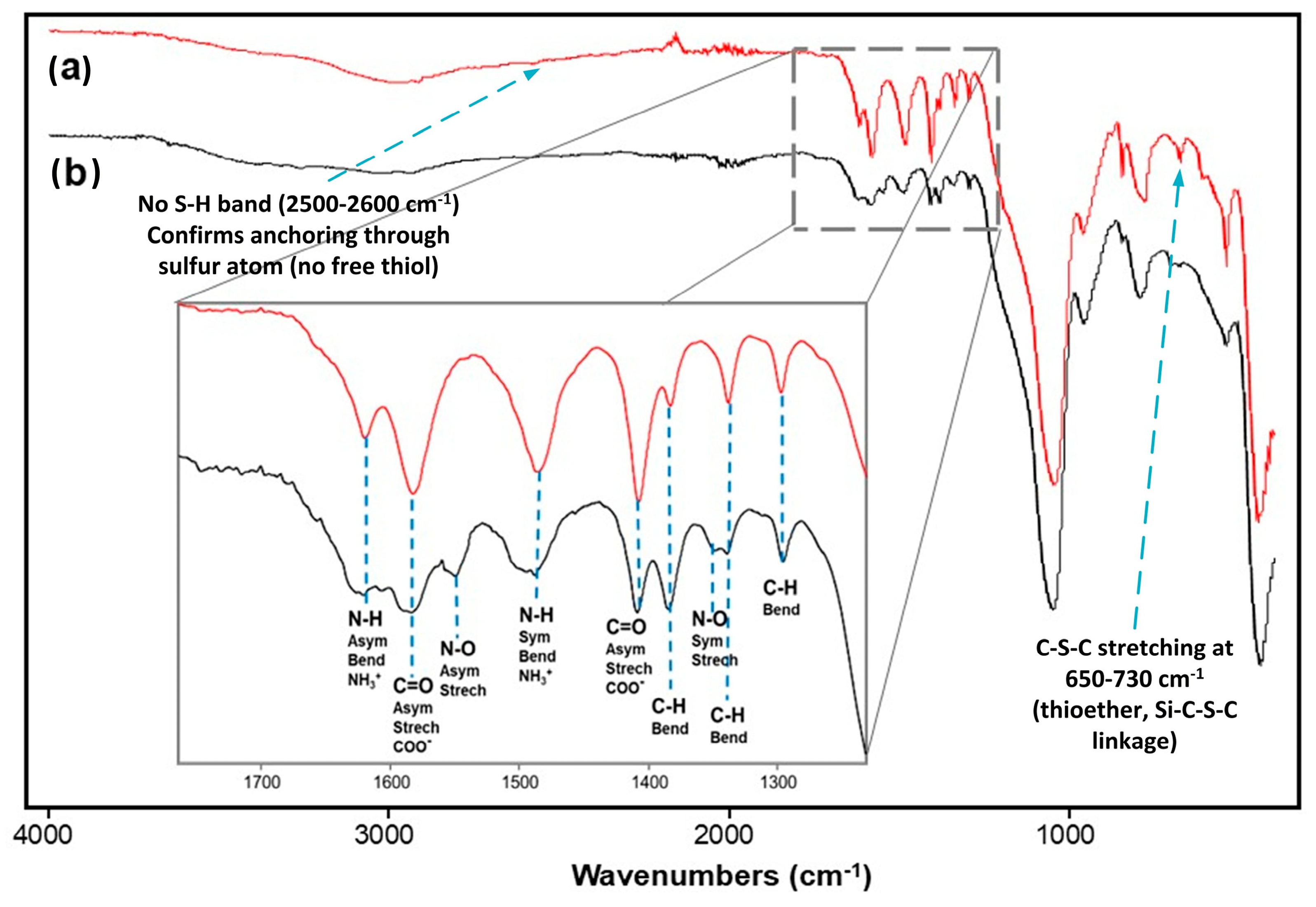

2.8. FTIR Analysis of the SG-3PS-Cys Adsorbent Before and After Hg(II) Uptake

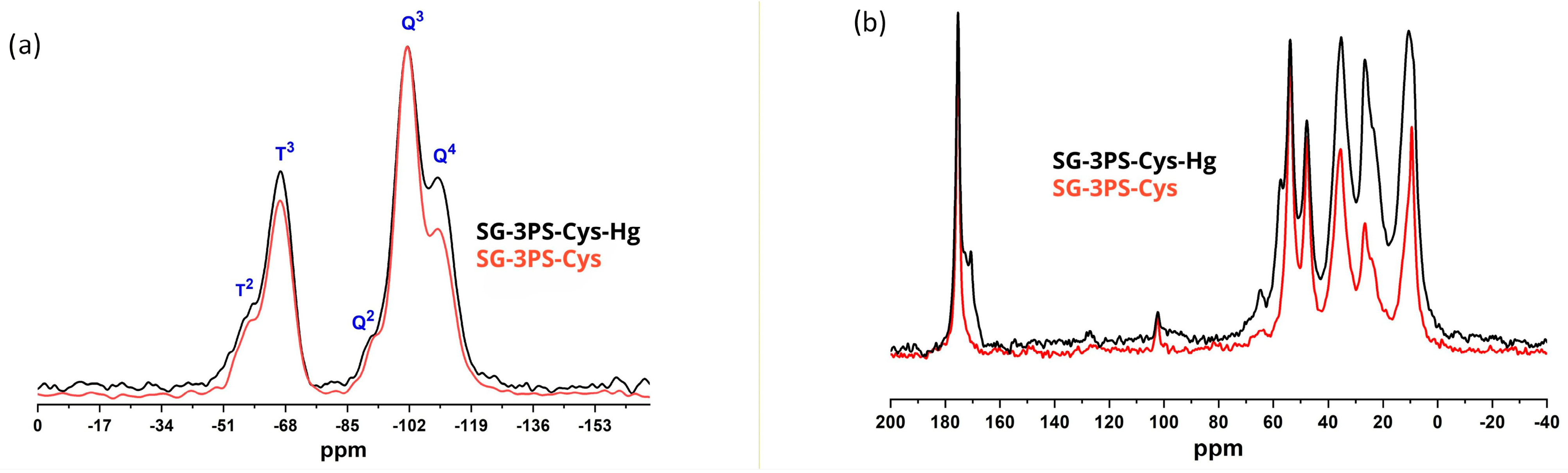

2.9. Solid-State NMR Analysis

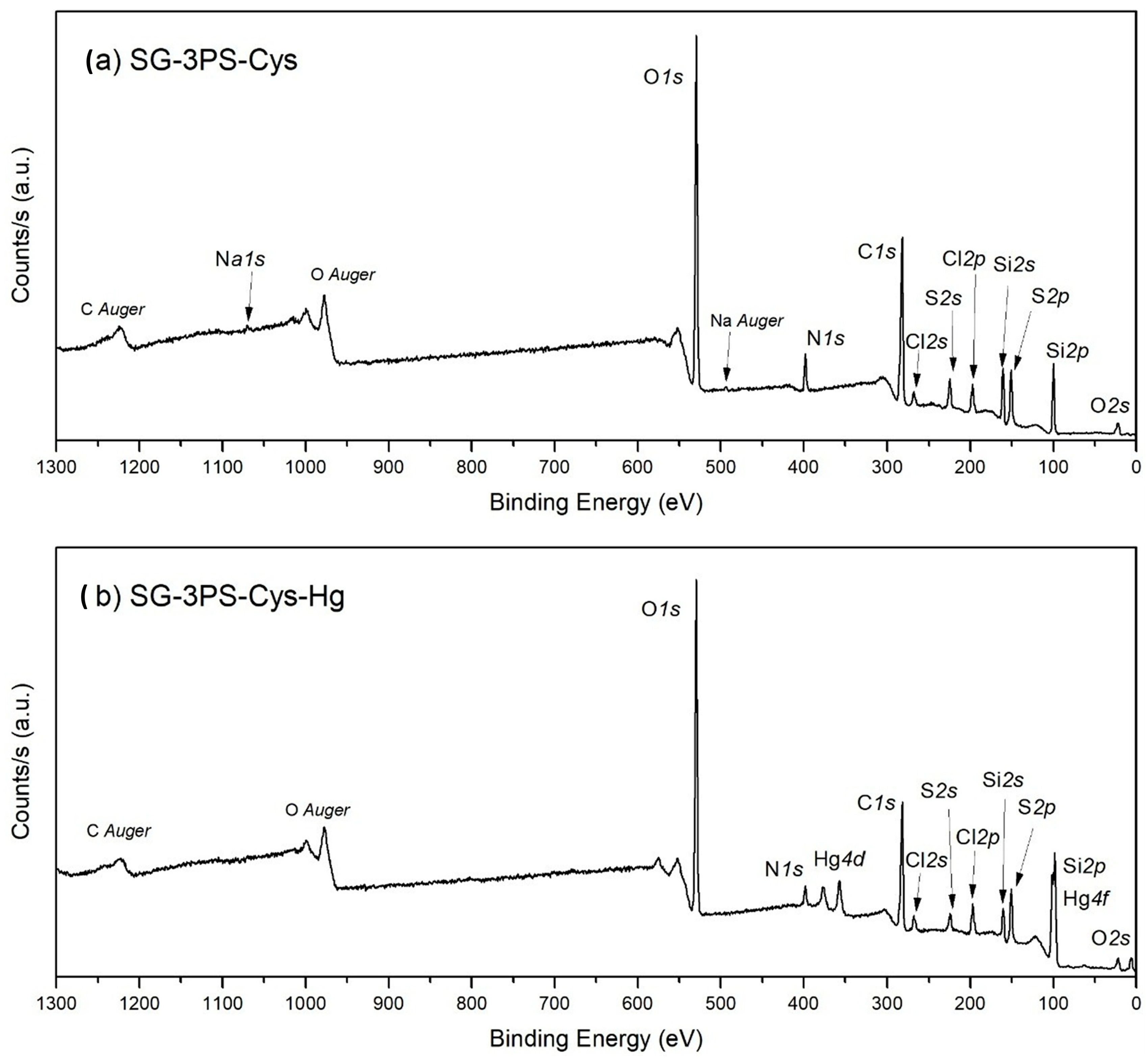

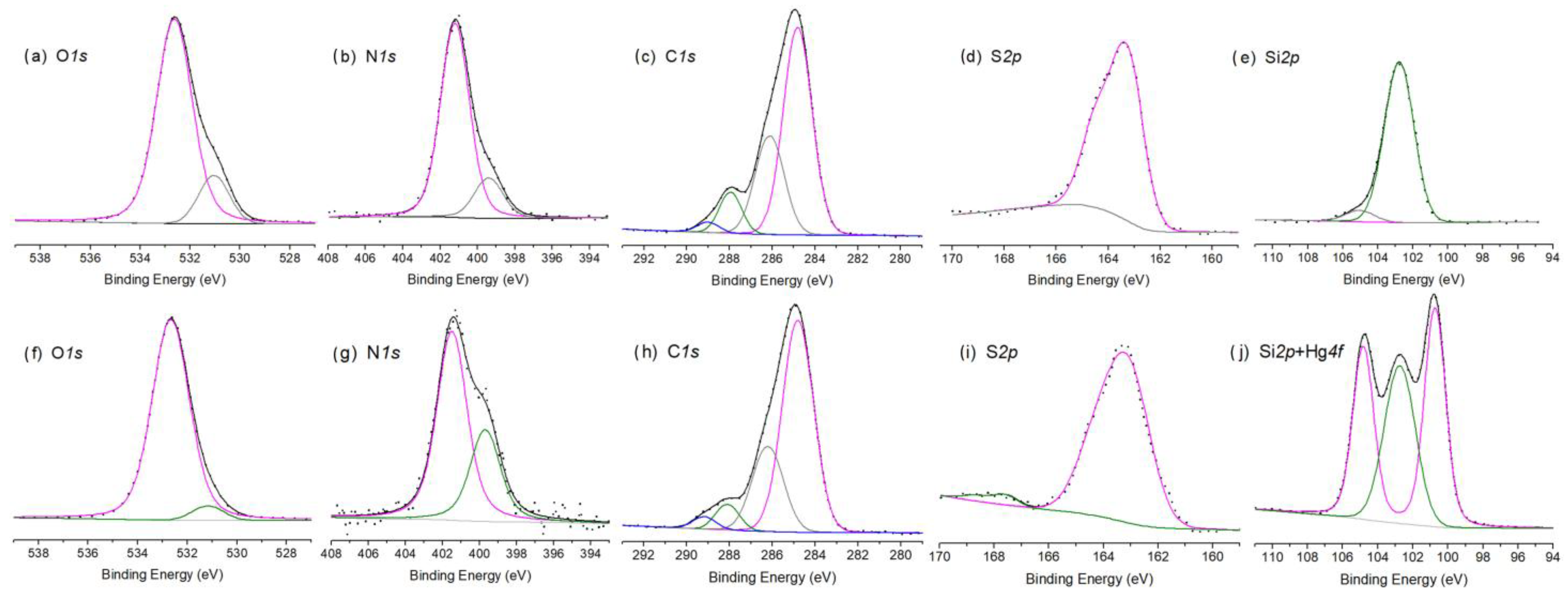

2.10. XPS Results

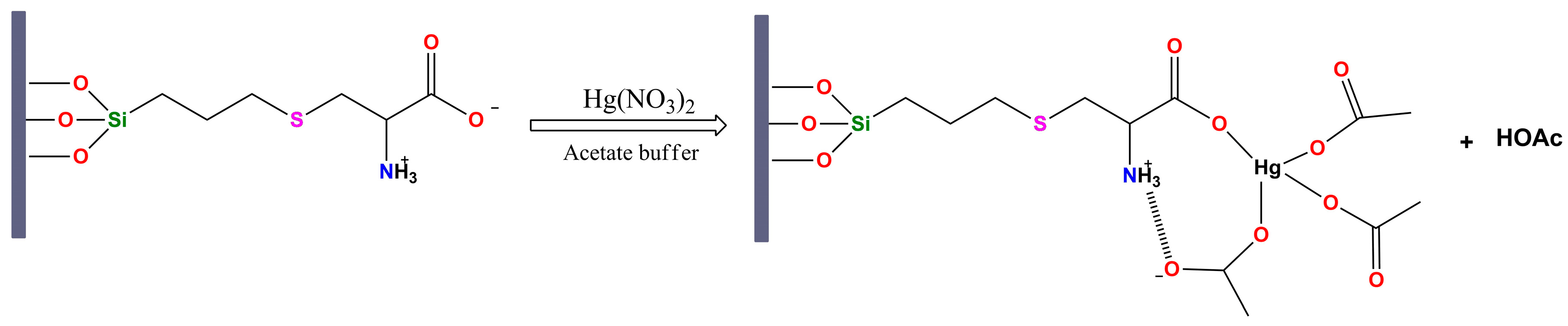

Mechanism of Hg(II) Uptake and Environmental Relevance

2.11. Surface Energy Distribution, Porous Structure, and Zeta Potential: Synergistic Influence on Mercury Uptake

3. Conclusions

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

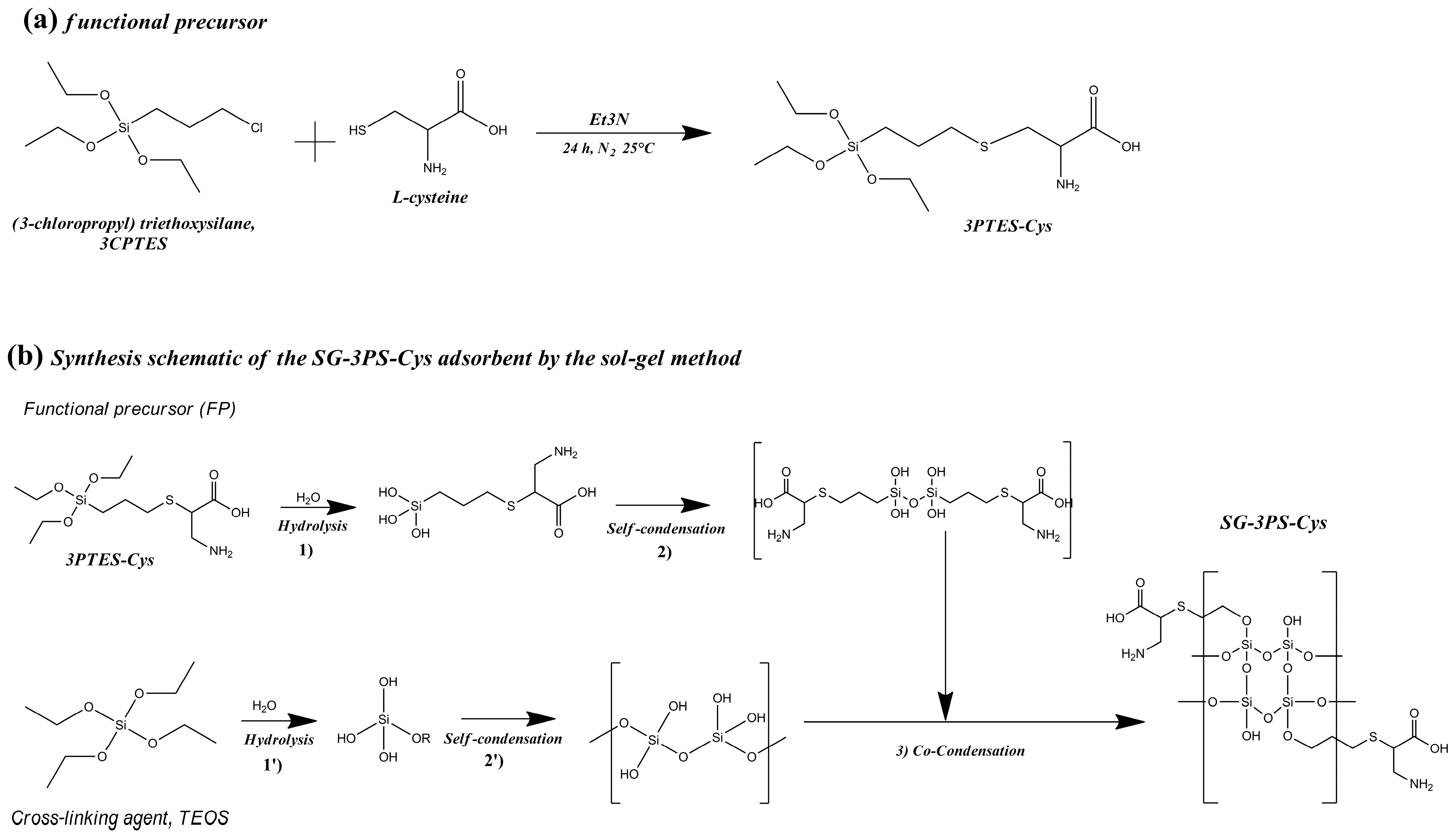

4.2. Synthesis of the Functional Precursor (3PTES-Cys)

4.3. Synthesis of the Cysteine-Functionalized Silica Adsorbent (SG-3PS-Cys)

4.4. Hg(II) Adsorption Kinetics

4.5. Equilibrium Adsorption Isotherms

4.6. Selectivity Toward Multi-Cation Solutions

4.7. Stability and Regeneration

4.8. Physicochemical Characterization of SG-3PS-Cys

4.9. FTIR Analysis

4.10. Solid-State NMR Spectroscopy

4.11. X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS)

4.12. Surface Energy Distribution Analysis

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Selin, N.E. Global Biogeochemical Cycling of Mercury: A Review. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2009, 34, 43–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kismelyeva, S.; Khalikhan, R.; Torezhan, A.; Kumisbek, A.; Akimzhanova, Z.; Karaca, F.; Guney, M. Potential Human Exposure to Mercury (Hg) in a Chlor-Alkali Plant Impacted Zone: Risk Characterization Using Updated Site Assessment Data. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horowitz, H.M.; Jacob, D.J.; Amos, H.M.; Streets, D.G.; Sunderland, E.M. Historical Mercury Releases from Commercial Products: Global Environmental Implications. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 10242–10250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Velzen, D.; Langenkamp, H.; Herb, G. Review: Mercury in waste incineration. Waste Manag. Res. J. A Sustain. Circ. Econ. 2002, 20, 556–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Mercury in Drinking-Water Background Document for Development of WHO Guidelines for Drinking-Water Quality. 2005. Available online: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/wash-documents/wash-chemicals/mercury-background-document.pdf (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- UNEP. Global Mercury Assessment. 2019. Available online: https://www.unep.org/resources/publication/global-mercury-assessment-2018 (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Azimi, A.; Azari, A.; Rezakazemi, M.; Ansarpour, M. Removal of Heavy Metals from Industrial Wastewaters: A Review. ChemBioEng Rev. 2017, 4, 37–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jyothi, N.R.; Farook, N.A.M. Mercury Toxicity in Public Health. In Heavy Metal Toxicity in Public Health; Intech Open: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.Z.; Hu, C.J.; Cheng, K.; Wei, B.M.; Hu, S.C. Removal of mercury from wastewater by adsorption using thiol-functionalized eggshell membrane. Adv. Mater. Res. 2010, 113–116, 22–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Himanshu Agarwal, H.A.; Divyanshi Sharma, D.S.; Sindhu, S.K.; Sonika Tyagi, S.T.; Saiqa Ikram, S.I. Removal of mercury from wastewater use of green adsorbents-a review. Electron. J. Environ. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 9, 1551–1558. [Google Scholar]

- Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. Toxicological Profile for Mercury Draft for Public Comment. 2022. Available online: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/TSP/ToxProfiles/ToxProfiles.aspx?id=115&tid=24 (accessed on 15 November 2023).

- Liang, R.; Zou, H. Removal of aqueous Hg(II) by thiol-functionalized nonporous silica microspheres prepared by one-step sol–gel method. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 18534–18542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wu, M.; Li, C.; Yu, P.; Feng, S.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Q. Interaction Structure and Affinity of Zwitterionic Amino Acids with Important Metal Cations (Cd2+, Cu2+, Fe3+, Hg2+, Mn2+, Ni2+ and Zn2+) in Aqueous Solution: A Theoretical Study. Molecules 2022, 27, 2407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Environmental Protection Agency. Water Quality Criterion for the Protection of Human Health; EPA-823-R-01-001; United States Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2001.

- World Health Organization. Guidelines for Drinking-Water Quality, 3rd ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, R.; Liu, G.; Li, M. Analysis of the effect of drying conditions on the structural and surface heterogeneity of silica aerogels and xerogel by using cryogenic nitrogen adsorption characterization. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2010, 129, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micromeritics Intrument Corp. Application Note: Surface Energy Distribution by DFT Analysis of Nitrogen Adsorption Data. 2018. Available online: https://www.micromeritics.com (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Diario Oficial de la federación. NOM- 001-SEMARNAT 2021. Que establece los límites permisibles de contaminantes en las descargas de aguas residuals en cuerpos receptores propiedad de la nación. Mexico. 2021. Available online: https://www.cofemersimir.gob.mx/portales/resumen/49271 (accessed on 10 June 2024).

- Stong, T.; Osuna, C.A.; Shear, H.; Sanchez, J.d.A.; Ramírez, G.; Torres, J.d.J.D. Mercury concentrations in common carp (Cyprinus carpio) in Lake Chapala, Mexico: A lakewide survey. J. Environ. Sci. Health A Tox. Hazard. Subst. Environ. Eng. 2013, 14, 1835–1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres, Z.; Mora, M.A.; Taylor, R.J.; Alvarez-Bernal, D.; Buelna, H.R.; Hyodo, A. Accumulation and hazard assessment of mercury to waterbirds at Lake Chapala, Mexico. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 6359–6365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.d.S.d.; de Moraes, D.P.; dos Santos, J.H.Z. Sol-gel hybrid silicas as an useful tool to mercury removal. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 103428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.; Guo, C.; Wang, L.; Xu, J.; Dong, H. Bacterial synthesis of PbS nanocrystallites in one-step with l-cysteine serving as both sulfur source and capping ligand. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adnan, S.; Kalwar, N.H.; Abbas, M.W.; Soomro, R.A.; Saand, M.A.; Awan, F.R.; Avci, A.; Pehlivan, E.; Bajwa, S. Enzyme-free colorimetric sensing of glucose using l-cysteine functionalized silver nanoparticles. SN Appl. Sci. 2019, 1, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomar, D.; Kaur, H.; Kaur, H.; Rana, B. ATR-FTIR Spectroscopy and Its Relevance to Probe the Molecular-Level Interactions Between Amino Acids and Metal-Oxide Nanoparticles at Solid/Aqueous Interface; Springer Proceedings in Physics; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 3–21. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-De-La-Peña, S.; Gómez-Salazar, S.; Gutiérrez-Ortega, J.A.; Badillo-Camacho, J.; Peregrina-Lucano, A.A.; Shenderovich, I.G.; Manríquez-González, R. Novel Silica Hybrid Adsorbent Functionalized with L-Glutathione Used for the Uptake of As(V) from Aqueous Media. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2022, 61, 4348–4362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, D.; Gupta, V.; Srivastava, S.; Chander, S. Kinetics of mercury adsorption from wastewater using activated carbon derived from fertilizer waste. Colloids Surfaces A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2001, 177, 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Ma, S.; He, Z.; Liu, H.; Pei, X. A revisit on intraparticle diffusion models with analytical solutions: Underlying assumption, application scope and solving method. J. Water Process. Eng. 2024, 60, 105241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plazinski, W.; Rudzinski, W.; Plazinska, A. Theoretical models of sorption kinetics including a surface reaction mechanism: A review. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2009, 152, 2–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Sun, Y.; Xu, X.; Qu, J.; Qu, B. Adsorption of Hg(II) in an Aqueous Solution by Activated Carbon Prepared from Rice Husk Using KOH Activation. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 29231–29242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tchobanoglous, G.; Burton, F.L.; Stensel, H.D. Wastewater Engineering Treatment and Reuse, 4th ed.; McGraw-Hill Education: North Ryde, NSW, Australia, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, R.M.; Martell, A.E.; Motekaitis, R.J. Critically Selected Stability Constants of Metal Complexes. 2004. Available online: https://www.nist.gov/system/files/documents/srd/46_8.pdf (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Giles, C.H.; MacEwan, T.H.; Nakhwa, S.N.; Smith, D. Studies in adsorption. Part XI. A system of classification of solution adsorption isotherms, and its use in diagnosis of adsorption mechanisms and in measurement of specific surface areas of solids. J. Chem. Soc. 1960, 3973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algieri, V.; Tursi, A.; Costanzo, P.; Maiuolo, L.; De Nino, A.; Nucera, A.; Castriota, M.; De Luca, O.; Papagno, M.; Caruso, T.; et al. Thiol-functionalized cellulose for mercury polluted water remediation: Synthesis and study of the adsorption properties. Chemosphere 2024, 355, 141891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, P.; Sarangi, R.; Hedman, B.; Hodgson, K.O. Synchrotron X-radiolysis of L-cysteine at the sulfur K-edge: Sulfurous products, experimental surprises, and dioxygen as an oxidoreductant. J. Chem. Phys. 2019, 150, 105101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamid, S.; Syed, W.; Mohammad, G. Synthesis and Characterization of Amino-functionalized Meso- porous Silicate MCM-41 for Removal of Toxic Metal Ions. Chin. J. Chem. 2009, 27, 915–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srikhaow, A.; Butburee, T.; Pon-On, W.; Srikhirin, T.; Uraisin, K.; Suttiponpanit, K.; Chaveanghong, S.; Smith, S.M. Efficient Mercury Removal at Ultralow Metal Concentrations by Cysteine Functionalized Carbon-Coated Magnetite. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 8262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katok, K.V.; Whitby, R.L.D.; Fayon, F.; Bonnamy, S.; Mikhalovsky, S.V.; Cundy, A.B. Synthesis and Application of Hydride Silica Composites for Rapid and Facile Removal of Aqueous Mercury. Chemphyschem 2013, 14, 4126–4133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Huang, Y.; Zhu, S.; Yao, Y. Enhanced Hg(II) removal by polyethylenimine-modified fly ash-based tobermorite. Colloids Surfaces A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2024, 702, 135101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johari, K.; Saman, N.; Mat, H. A comparative evaluation of mercury(II) adsorption equilibrium and kinetics onto silica gel and sulfur-functionalized silica gels adsorbents. Can. J. Chem. Eng. 2014, 92, 1048–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, M.; Ram, B.; Chauhan, G.S.; Kaushik, A. L-Cysteine functionalized bagasse cellulose nanofibers for mercury (II) ions adsorption. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 112, 728–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thommes, M.; Cychosz, K.A. Physical adsorption characterization of nanoporous materials: Progress and challenges. Adsorption 2014, 20, 233–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natusch, D.F.S.; Porter, L.J. Direct detection of mercury(II)–thio-ether bonding in complexes of methionine and S-methylcysteine by 1H nuclear magnetic resonance. J. Chem. Soc. D Chem. Commun. 1970, 10, 596–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayalath, S.; Larsen, S.C.; Grassian, V.H. Surface adsorption of Nordic aquatic fulvic acid on amine-functionalized and non-functionalized mesoporous silica nanoparticles. Environ. Sci. Nano 2018, 5, 2162–2171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, S.F. Assignment of the vibrational spectrum of l-cysteine. Chem. Phys. 2013, 424, 75–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebben, D.; Pendleton, P. Infrared spectrum analysis of the dissociated states of simple amino acids. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2014, 132, 706–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, K.L.; Yao, M.Y.; Wang, D.B.; Zhao, H.C.; Cheng, G.W.; Yang, S. Removal of Hg2+ from flue gas by petroleum thioether. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 354, 012094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurihara, T.; Noda, Y.; Takegoshi, K. Capping Structure of Ligand–Cysteine on CdSe Magic-Sized Clusters. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 3476–3483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamoto, K. Infrared Spectra of Inorganic and Coordination Compounds, 6th ed.; John Wiley, Sons, Wiley and Sons Publications: New York, NY, USA, 1963; pp. 222–224. [Google Scholar]

- Di Michele, A.; Diodati, P.; Morresi, A.; Sassi, P. Mercury acetate produced by metallic mercury subjected to acoustic cavitation in a solution of acetic acid in water. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2009, 16, 141–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trochimczuk, A.W. Chelating resins with N-substituted diamides of malonic acid as ligands. Eur. Polym. J. 1998, 34, 1657–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vickerman, J.C.; Gilmore, I.S.; Ian, S. Surface Analysis: The Principal Techniques; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Herrera-Gomez, A. Uncertainties in photoemission peak fitting accounting for the covariance with background parameters. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A Vac. Surf. Film. 2020, 38, 033211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beamson, G.; Briggs, D. High Resolution XPS of Organic Polymers: The Scienta ESCA300 Database. J. Chem. Educ. 1993, 70, A25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, O.; Odio, O.F.; Reguera, E. XPS as a probe for the bonding nature in metal acetates. New J. Chem. 2022, 46, 11255–11265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schecher, W.D.; McAvoy, D.C. MINEQL+: A Chemical Equilibrium Program for Personal Computers, 3rd ed.; Procter & Gamble Company: Cincinnati, OH, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, J.; Luo, L.; Zhang, J.; Christie, P.; Zhang, S. Adsorption of mercury on lignin: Combined surface complexation modeling and X-ray absorption spectroscopy studies. Environ. Pollut. 2012, 162, 255–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sing, K. The use of nitrogen adsorption for the characterization of porous materials. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2001, 187–188, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandosz, T.J. Activated Carbon Surfaces in Environmental Remediation, 1st ed.; Interface Science and Technology; Elsevier: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kruk, M.; Jaroniec, M. Gas Adsorption Characterization of Ordered Organic−Inorganic Nanocomposite Materials. Chem. Mater. 2001, 13, 3169–3183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thielemann, J.P.; Girgsdies, F.; Schlögl, R.; Hess, C. Pore structure and surface area of silica SBA-15: Influence of washing and scale-up. Beilstein J. Nanotechnol. 2011, 2, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baalousha, M. Aggregation and disaggregation of iron oxide nanoparticles: Influence of particle concentration, pH and natural organic matter. Sci. Total. Environ. 2009, 407, 2093–2101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran-Salazar, R.G.; Carbajal-Arizaga, G.G.; Gutierréz-Ortega, J.A.; Badillo-Camacho, J.; Manríquez-González, R.; Shenderovich, I.G.; Gómez-Salazar, S. As(V) removal from aqueous media using an environmentally friendly zwitterion L-cysteine functionalized silica adsorbent. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2023, 278, 118879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinker, J.C.; Scherer, G.W. Sol-Gel Science; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Quirarte-Escalante, C.A.; Soto, V.; de la Cruz, W.; Porras, G.R.; Manríquez, R.; Gomez-Salazar, S. Synthesis of Hybrid Adsorbents Combining Sol−Gel Processing and Molecular Imprinting Applied to Lead Removal from Aqueous Streams. Chem. Mater. 2009, 21, 1439–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yang, Y.; Ding, J. Information criteria for model selection. WIREs Comput. Stat. 2023, 15, e1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akcakayiran, D.; Mauder, D.; Hess, C.; Sievers, T.K.; Kurth, D.G.; Shenderovich, I.; Limbach, H.-H.; Findenegg, G.H. Carboxylic Acid-Doped SBA-15 Silica as a Host for Metallo-supramolecular Coordination Polymers. J. Phys. Chem. B 2008, 112, 14637–14647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shenderovich, I.G. Experimentally Established Benchmark Calculations of 31 P NMR Quantities. Chem. Methods 2021, 1, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Ortega, J.A.; Gómez-Salazar, S.; Shenderovich, I.G.; Manríquez-González, R. Efficiency and lead uptake mechanism of a phosphonate functionalized mesoporous silica through P/Pb association ratio. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2020, 239, 122037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shenderovich, I.G.; Mauder, D.; Akcakayiran, D.; Buntkowsky, G.; Limbach, H.-H.; Findenegg, G.H. NMR Provides Checklist of Generic Properties for Atomic-Scale Models of Periodic Mesoporous Silicas. J. Phys. Chem. B 2007, 111, 12088–12096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eichele, K. WSolids1-Solid State NMR Simulations User Manual. 2021, pp. 1–102. Available online: http://anorganik.uni-tuebingen.de/klaus/soft/wsolids1/wsolids1.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2024).

| Model/Parameters | Initial Solution Concentration, mg L−1 | Equation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 93 | 318 | 593 | ||

| qmax exp (mg g−1) | 4.05 | 19.97 | 35.11 | |

| Pseudo-first order | ||||

| qmax calc (mg g−1) | 4.13 ± 0.18 | 17.86 ± 0.52 | 33.28 ± 0.85 | |

| k1 (min−1) | 0.007 ± 0.001 | 0.039 ± 0.002 | 0.112 ± 0.004 | |

| R2 | 0.933 | 0.882 | 0.920 | |

| AIC/ΔAIC | −58.8/10.9 | −43.9/10.4 | −53.3/3.1 | |

| Pseudo-second order | ||||

| qmax calc (mg g−1) | 5.64 ± 0.23 | 19.80 ±0.47 | 35.49 ± 0.92 | |

| k2 (g mg min−1) | 0.001 ± 0.0001 | 0.002 ± 0.0002 | 0.004 ± 0.0003 | |

| R2 | 0.927 | 0.919 | 0.923 | |

| AIC/ΔAIC | −58.6/11.1 | −54.3/0.0 | −53.9/2.5 | |

| Intraparticle diffusion | ||||

| A (mg g−1 min−1/2) | 0.226 ± 0.012 | 0.874 ± 0.029 | 1.237 ± 0.041 | |

| B (mg g−1 min−1) | −0.502 ± 0.030 | 3.413 ± 0.042 | 14.19 ± 0.06 | |

| R2 | 0.903 | 0.763 | 0.569 | |

| AIC/ΔAIC | −49.6/20.1 | −25.4/28.9 | −8.7/47.7 | |

| Avrami | ||||

| qmax calc (mg g−1) | 3.47 ± 0.20 | 18.3 ± 0.45 | 32.8 ± 0.71 | |

| Ka (min−1) | 0.037 ± 0.002 | 0.019 ± 0.002 | 0.172 ± 0.010 | |

| Na | 7.148 ± 0.218 | 0.642 ± 0.050 | 1.573 ± 0.081 | |

| R2 | 0.971 | 0.895 | 0.940 | |

| AIC/ΔAIC | −69.7/0.0 | −47.4/6.9 | −56.4/0.0 | |

| Models | Initial Solution pH | Equation | ||

| 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| qmax exp (mg g−1) | 82.67 | 33.61 | 31.98 | |

| Lagmuir | ||||

| qmax (mg g−1) | 82.01 | 32 | 33 | |

| K (L mg−1) | 0.009 | 0.002 | 0.002 | |

| R2 | 0.677 | 0.628 | 0.726 | |

| Freundlich | ||||

| Kf (mg1−1/n L1/n g−1) | 1.408 | 0.420 | 0.524 | |

| n | 1.501 | 1.700 | 1.800 | |

| R2 | 0.786 | 0.716 | 0.771 | |

| Toth | ||||

| qmax (mg g−1) | 82.01 | 32 | 33 | |

| aT (L/mg) | 0.004 | 0.0008 | 0.0008 | |

| t | 8.136 | −4597 | −6 × 106 | |

| R2 | 0.911 | −0.034 | −0.437 | |

| S-shape | ||||

| No (mg g−1) | 74.47 | 32.43 | 33.56 | |

| k1 | 0.038 | 0.013 | 0.006 | |

| k2 | 303.8 | 13,314 | 56.69 | |

| R2 | 0.989 | 0.957 | 0.970 | |

| Langmuir two sites | ||||

| qmax1 (mg g−1) | 82 | 0.0002 | 2041 | |

| qmax2 (mg g−1) | 5 | 3.555 | −1.869 | |

| b1 | 0.007 | −1.2 × 10−10 | 1.5 × 10−5 | |

| b2 | 0.050 | −9 × 1044 | 4.7 × 1046 | |

| R2 | 0.700 | −0.808 | 0.933 | |

| Freundlich-Langmuir | ||||

| qmax1 (mg g−1) | 80.73 | 32.53 | 36.82 | |

| KFL | 0.007 | 0.002 | 0.002 | |

| n | 0.225 | 0.108 | 0.285 | |

| R2 | 0.995 | 0.952 | 0.956 | |

| Adsorbent | Functional Group | qₘₐₓ (mg/g) | Binding Mechanism | Regeneration | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MPTMS MCM 41–NH2 | Aminopropyl (–NH2) grafted on MCM 41 | 125 | Hg–N coordination | Yes (10 cycles, water regeneration) | [35] |

| Cys C@Fe3O4 (carbon-coated magnetite) | –SH, –NH2, –COOH | 94.3 | Hg–S/N coordination | Yes (3 cycles) | [36] |

| Hydride silica composites | –Si–H (hydride) groups | ~101 | Hg–Si/H interactions | Not evaluated | [40] |

| PEI modified tobermorite | Polyethyleneimine (–NH2-rich) | 82.6 | Hg–N chelation | Yes | [38] |

| MPTMS-functionalized silica | –SH (MPTMS grafted) | 102.4 | Hg–S binding | Not specified | [39] |

| SG-3PS-Cys silica (no free –SH) | –NH3+, –COO− (no –SH) | 82.7 | Hg–N/Hg–O (zwitterionic, thiol-free) | Yes (~72% retained after 5 cycles) | This work |

| Sample | SBET (m2 g−1) | CBET | Vp (cm3 g−1) | Dp (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SG-3PS-Cys | 134.0 | 433.7 | 0.181 | 9.8 |

| SG-3PS-Cys-Hg | 188.6 | 1344 | 0.152 | 7.1 |

| Sample | O1s, C1s, Si2p | N1s | S2p | Hg4f |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SG-3PS-Cys | 89.0% | 3.9% | 7.1% | -- |

| SG-3PS-Cys-Hg | 88.8% | 3.0% | 6.1% | 2.1% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Moran-Salazar, R.G.; Manríquez-González, R.; Peregrina-Lucano, A.A.; Gutierréz-Ortega, J.A.; Lara, A.; Orozco-Guareño, E.; Macias-Lamas, A.M.; Badillo-Camacho, J.; Shenderovich, I.G.; Vazquez-Lepe, M.; et al. From Surface Energetics to Environmental Functionality: Mechanistic Insights into Hg(II) Removal by L-Cysteine-Modified Silica Gel. Gels 2026, 12, 141. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12020141

Moran-Salazar RG, Manríquez-González R, Peregrina-Lucano AA, Gutierréz-Ortega JA, Lara A, Orozco-Guareño E, Macias-Lamas AM, Badillo-Camacho J, Shenderovich IG, Vazquez-Lepe M, et al. From Surface Energetics to Environmental Functionality: Mechanistic Insights into Hg(II) Removal by L-Cysteine-Modified Silica Gel. Gels. 2026; 12(2):141. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12020141

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoran-Salazar, Rene G., Ricardo Manríquez-González, Alejandro A. Peregrina-Lucano, José A. Gutierréz-Ortega, Agustín Lara, Eulogio Orozco-Guareño, Adriana M. Macias-Lamas, Jessica Badillo-Camacho, Ilya G. Shenderovich, Milton Vazquez-Lepe, and et al. 2026. "From Surface Energetics to Environmental Functionality: Mechanistic Insights into Hg(II) Removal by L-Cysteine-Modified Silica Gel" Gels 12, no. 2: 141. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12020141

APA StyleMoran-Salazar, R. G., Manríquez-González, R., Peregrina-Lucano, A. A., Gutierréz-Ortega, J. A., Lara, A., Orozco-Guareño, E., Macias-Lamas, A. M., Badillo-Camacho, J., Shenderovich, I. G., Vazquez-Lepe, M., & Gómez-Salazar, S. (2026). From Surface Energetics to Environmental Functionality: Mechanistic Insights into Hg(II) Removal by L-Cysteine-Modified Silica Gel. Gels, 12(2), 141. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12020141