Fabrication and Characterization of Lignocellulose-Based Porous Materials via Chemical Crosslinking

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

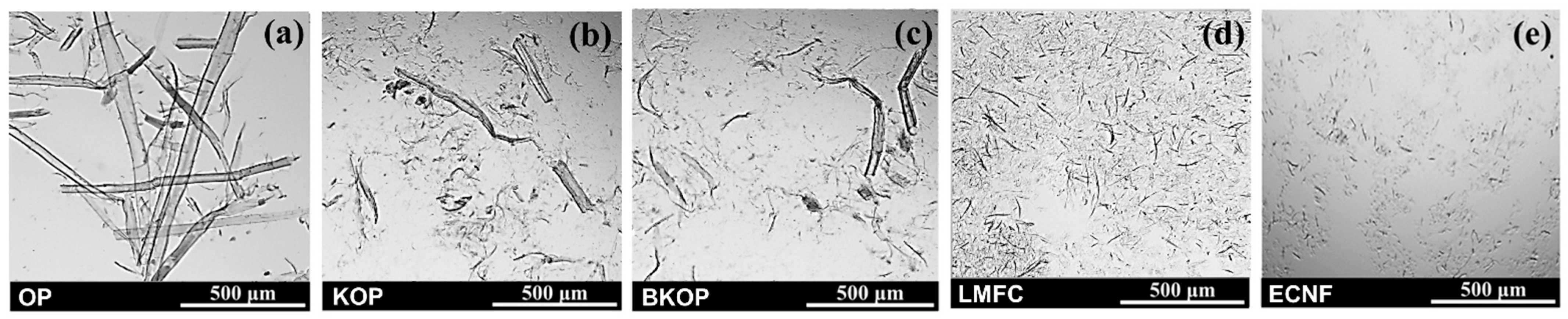

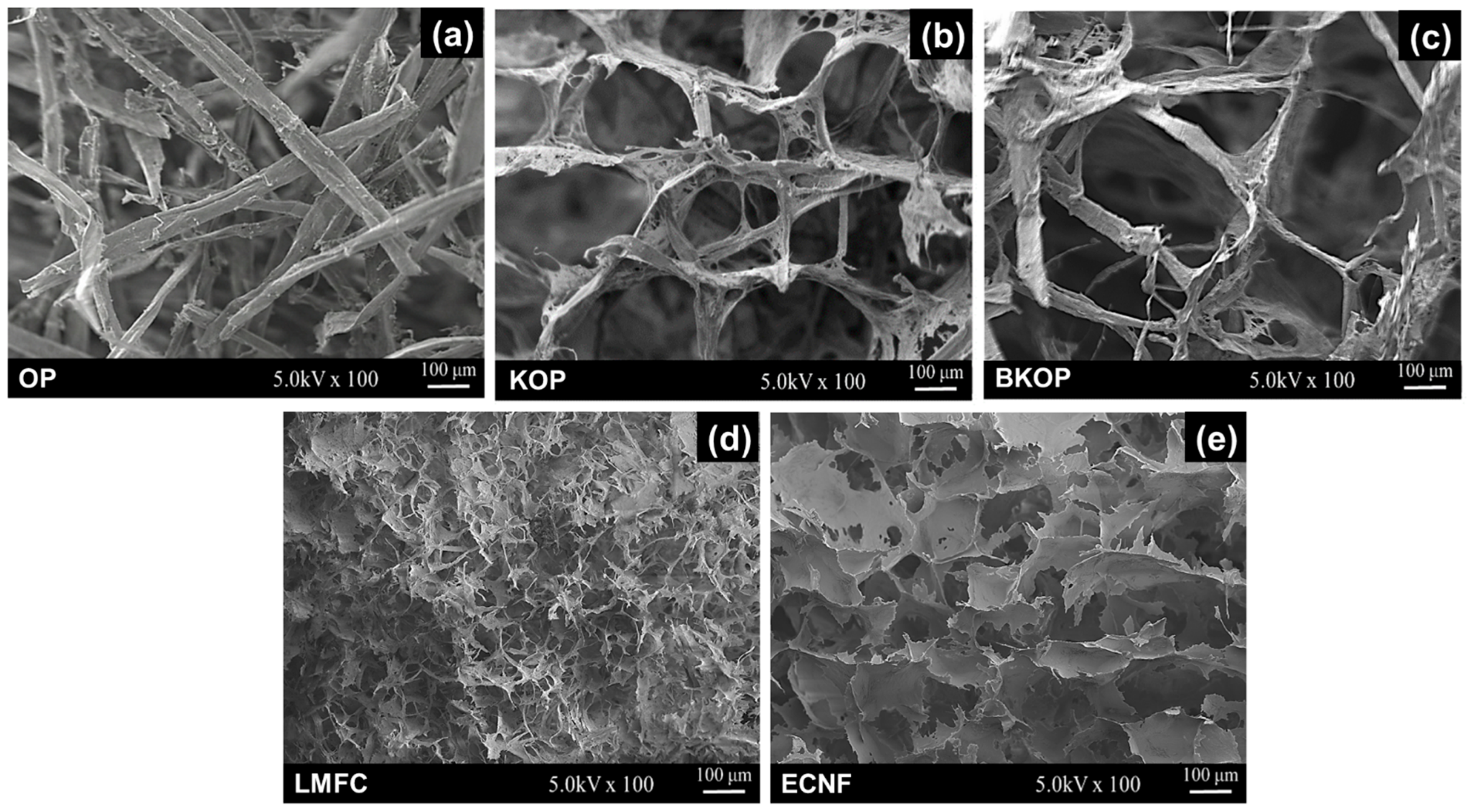

2.1. Fiber Properties

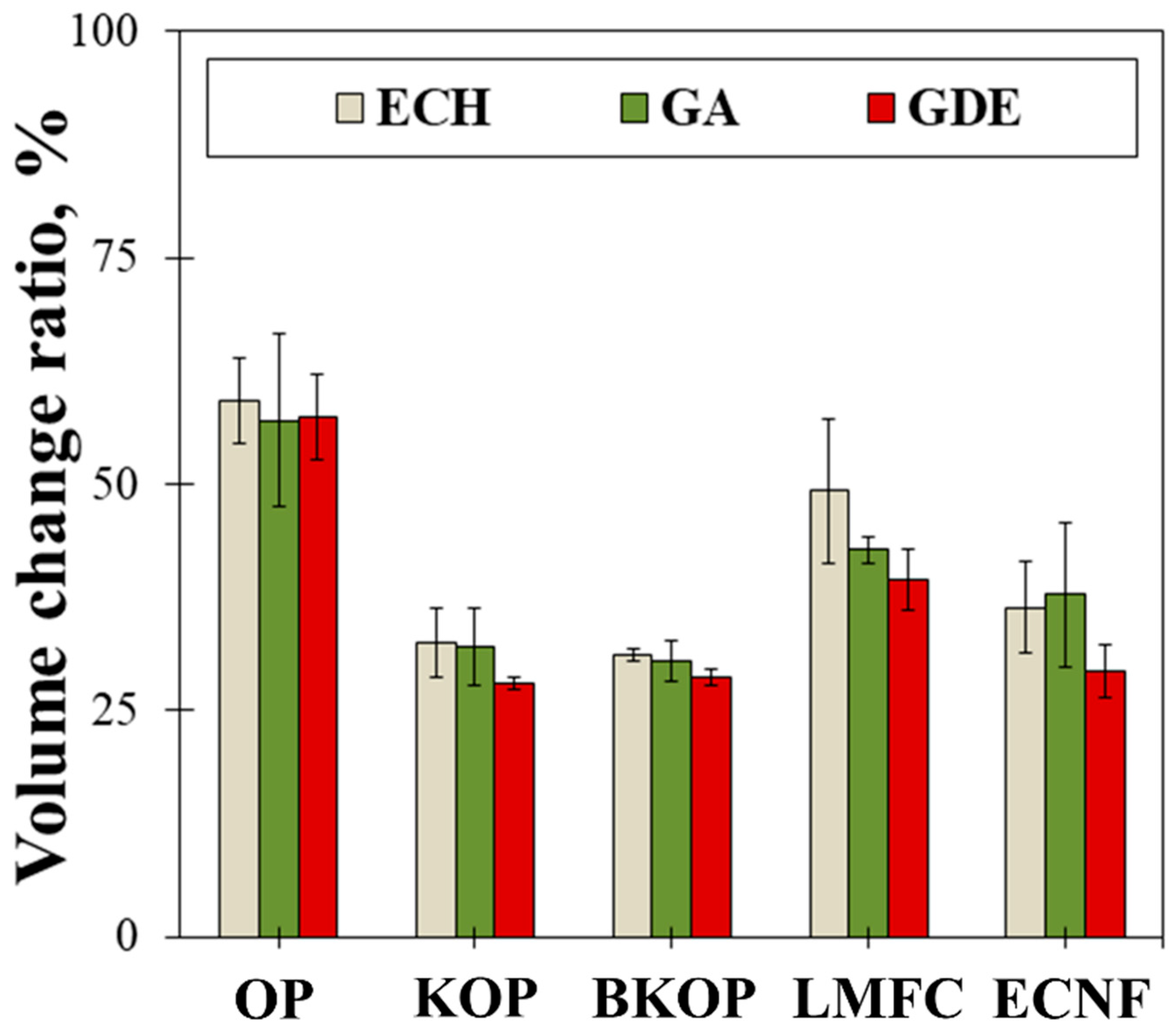

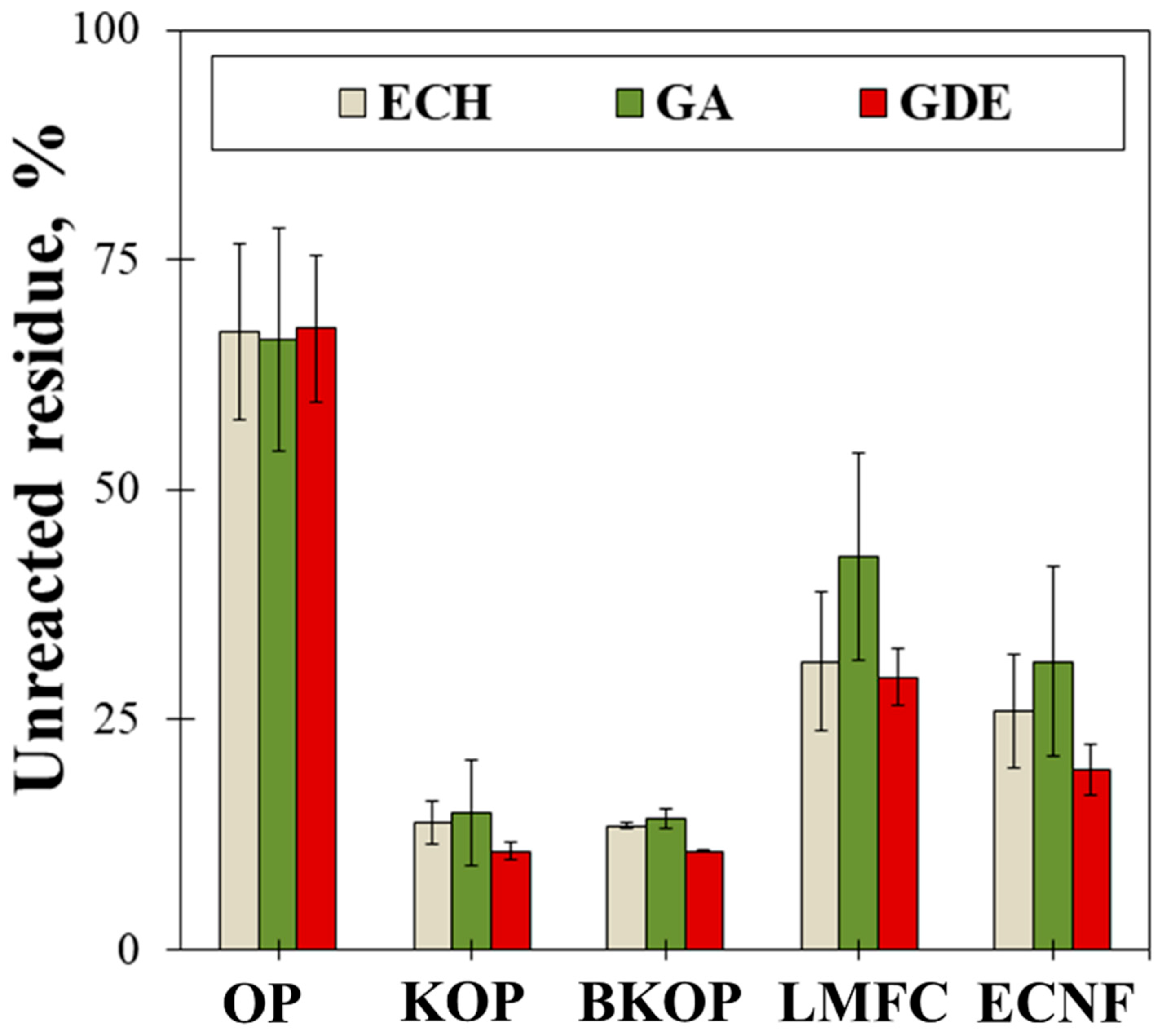

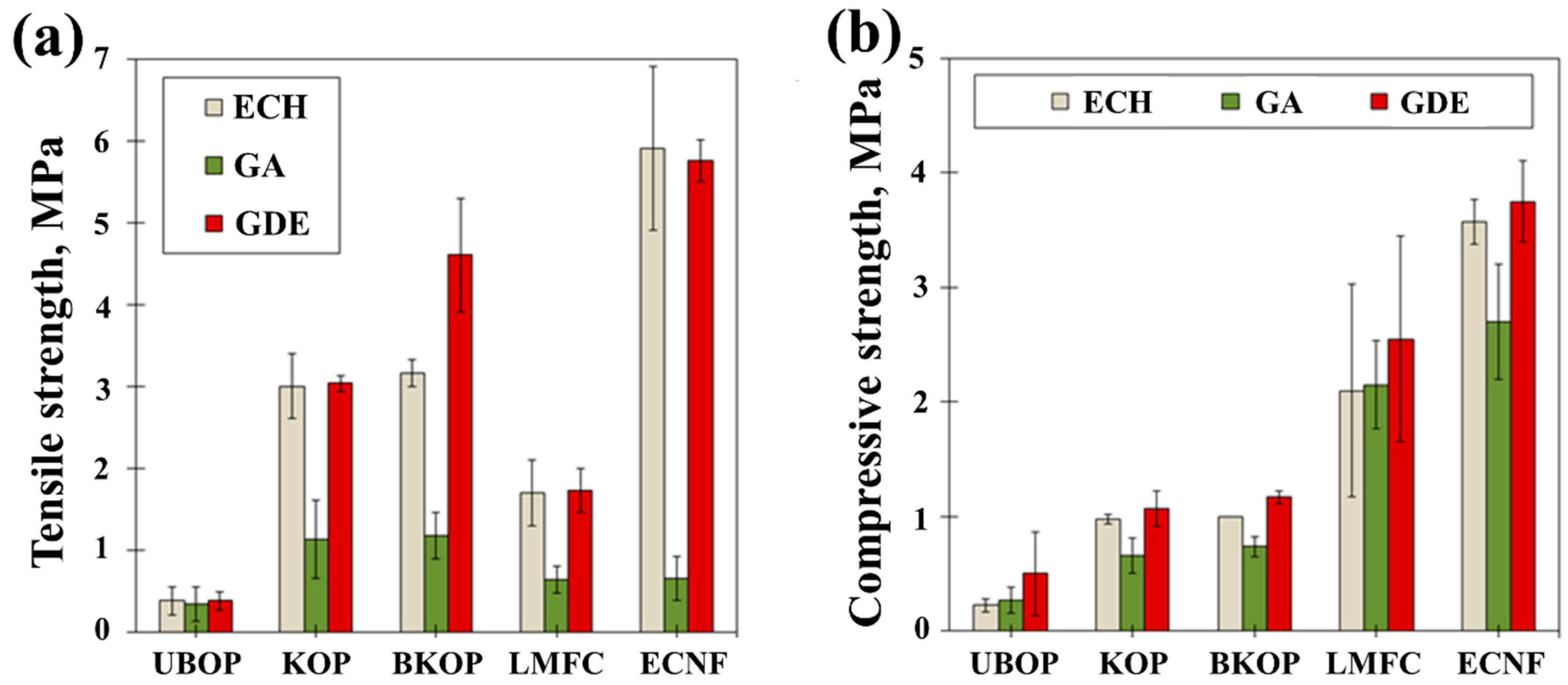

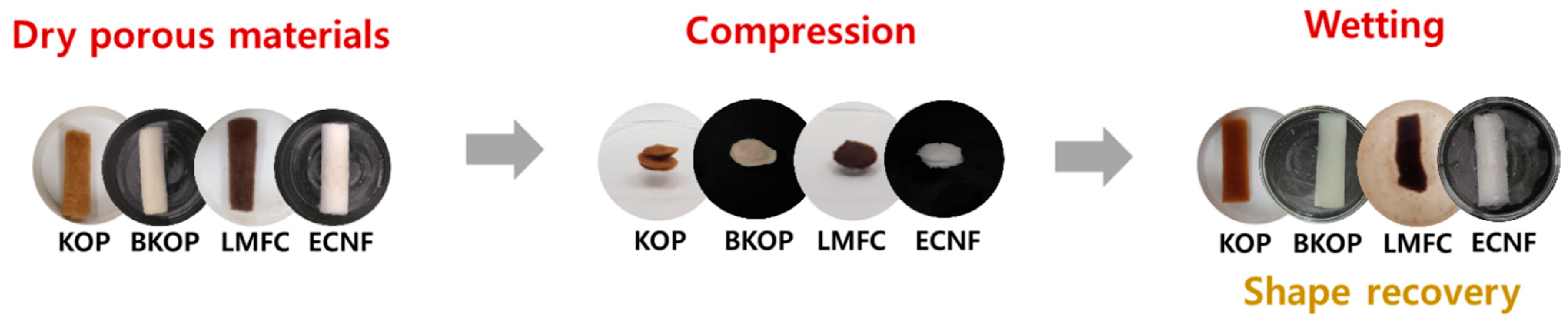

2.2. Properties of the Prepared Porous Materials

3. Conclusions

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

4.1.1. Organosolv Pulp (OP)

4.1.2. Kneaded Organosolv Pulp (KOP)

4.1.3. Bleached and Kneaded Organosolv Pulp (BKOP)

4.1.4. Lignin-Rich Microfibrillated Cellulose (LMFC)

4.1.5. Enzyme Cellulose Nanofiber (ECNF)

4.1.6. Crosslinking Agent and Catalyst

4.2. Fabrication of Porous Material

4.3. Measurement

4.3.1. Fiber Characterization

4.3.2. Characterization of the Porous Materials

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BET | Brunauer–Emmett–Teller |

| BKOP | Bleached and alkali-kneaded organosolv pulp |

| CNF | Cellulose nanofiber |

| CO2 | Carbon dioxide |

| ECH | Epichlorohydrin |

| ECNF | Enzyme cellulose nanofiber |

| GA | Glutaraldehyde |

| GDE | Glycerol diglycidyl ether |

| KOP | Alkali-kneaded organosolv pulp |

| LMFC | Lignin-rich microfibrillated cellulose |

| MFC | Microfibrillated cellulose |

| NaOH | Sodium hydroxide |

| OP | Organosolv pulp |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscopy |

References

- Choi, H.; Park, J.; Lee, J. Sustainable bio-based superabsorbent polymer: Poly(itaconic acid) with superior swelling properties. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2022, 4, 4098–4108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudiyanselage, T.K.; Neckers, D.C. Highly absorbing superabsorbent polymer. J. Polym. Sci. A Polym. Chem. 2008, 46, 1357–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Chen, M.; Zhou, X.; Lu, L.; Li, Y.; Gong, C.; Cheng, X. Water absorption and water/fertilizer retention performance of superabsorbent polymer-modified sulphoaluminate cementitious materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 150, 538–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.R.; Hu, Y.; Mao, S.; Mao, J.; Eneji, A.E.; Xue, X. Effectiveness of a water-saving superabsorbent polymer in soil water conservation for corn (Zea mays L.) based on ecophysiological parameters. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2011, 91, 1998–2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farkish, A.; Fall, M. Rapid dewatering of oil sand mature fine tailings using superabsorbent polymer (SAP). Miner. Eng. 2013, 50, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Nishiyama, Y.; Wada, M.; Kuga, S. Nanofibrillar cellulose aerogels. Colloids Surf. A 2004, 240, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, F.; Rigacci, A.; Pirard, R.; Berthon-Fabry, S.; Achard, P. Cellulose-based aerogels. Polymer 2006, 47, 7636–7645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aulin, C.; Netrval, J.; Wågberg, L.; Lindström, T. Aerogels from nanofibrillated cellulose with tunable oleophobicity. Soft Matter 2010, 6, 3298–3305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heath, L.; Thielemans, W. Cellulose nanowhisker aerogels. Green Chem. 2010, 12, 1448–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, R.T.; Azizi Samir, M.A.S.; Salazar-Alvarez, G.; Belova, L.; Ström, V.; Berglund, L.A.; Gedde, U.W. Flexible magnetic aerogels and stiff magnetic nanopaper using cellulose nanofibrils as templates. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2010, 5, 584–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, B.; Zhang, J.; Mi, Q.; Yu, J.; Song, R.; Zhang, J. Transparent cellulose–silica composite aerogels with excellent flame retardancy via in situ sol–gel process. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 11117–11123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korhonen, O.; Budtova, T. All-cellulose composite aerogels and cryogels. Compos. Part. A 2020, 137, 106027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Zhang, S.; Yang, B.; Hao, M.; Chen, Z.; Liu, Y.; Yao, J. Ambient-dried multifunctional cellulose aerogels prepared by freeze-linking technique. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 477, 147044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yu, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Wang, H. Effect of freezing speed and hydrogel concentration on microstructure and compressive performance of bamboo-based cellulose aerogels. J. Wood Sci. 2015, 61, 595–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Wan, L.; Li, Q.; Sun, X.; Natan, A.; Cao, D.; Zhu, H. Ice-templated anisotropic flame-resistant boron nitride aerogels enhanced through surface modification and cellulose nanofibrils. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2021, 3, 1358–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erlandsson, J.; Pettersson, T.; Ingverud, T.; Granberg, H.; Larsson, P.A.; Malkoch, M.; Wågberg, L. Mechanism of freezing-induced chemical crosslinking in ice-templated cellulose nanofibril aerogels. J. Mater. Chem. A 2018, 6, 19371–19380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solt, P.; Konnerth, J.; Gindl-Altmutter, W.; Kantner, W.; Moser, J.; Mitter, R.; van Herwijnen, H.W. Technological performance of formaldehyde-free adhesive alternatives for the particleboard industry. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2019, 94, 99–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias, A.; González-García, S.; Feijoo, G.; Moreira, M.T. Environmental benefits of soy-based bio-adhesives as alternatives to formaldehyde-based options. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 29781–29794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrobak, J.; Iłowska, J.; Chrobok, A. Formaldehyde-free resins for the wood-based panel industry: Alternatives and novel hardeners. Molecules 2022, 27, 4862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussin, M.H.; Abd Latif, N.H.; Hamidon, T.S.; Idris, N.N.; Hashim, R.; Appaturi, J.N.; Sedliačik, J. High-performance bio-based wood adhesives: A critical review. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2022, 21, 3909–3946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.R.; Lee, J.M. Comparison of fibrillation characteristics of unbleached kraft pulp and organosolv pulp by alkali kneading process. J. Korea TAPPI 2020, 52, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinu, R.; Mija, A. Cross-linked polyfuran networks with elastomeric behavior based on humins biorefinery by-products. Green Chem. 2019, 21, 6277–6289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berto, G.L.; Mattos, B.D.; Rojas, O.J.; Arantes, V. Single-step fiber pretreatment with monocomponent endoglucanase: Defibrillation energy and cellulose nanofibril quality. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 2260–2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Tian, D.; Renneckar, S.; Saddler, J.N. Enzyme-mediated nanofibrillation of cellulose by synergistic actions of endoglucanase, LPMO, and xylanase. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 3195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, J.; Zeng, Z.; Cheng, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, B.; Gao, W. Cellulose nanofibrils manufactured by various methods for paper strength additives. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 11918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, Y.; Peng, Y.; Strand, A.; Fu, S.; Sundberg, A.; Retulainen, E. Fiber evolution during alkaline treatment and its impact on handsheet properties. BioResources 2018, 13, 7310–7324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza Fonseca, A.; Panthapulakkal, S.; Konar, S.K.; Sain, M.; Bufalino, L.; Raabe, J.; Tonoli, G.H.D. Improving cellulose nanofibrillation of non-wood fibers using alkaline and bleaching pretreatments. Ind. Crops Prod. 2019, 131, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klunklin, W.; Hinmo, S.; Thipchai, P.; Rachtanapun, P. Effect of bleaching processes on physicochemical and functional properties of cellulose and carboxymethyl cellulose from coconut coir. Polymers 2023, 15, 3376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.J.; Hong, S.B.; Eom, T.J. Preparation of eucalyptus pulp under mild low-temperature atmospheric conditions using high-boiling-point solvent. Cellulose 2018, 25, 753–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, R.N.; DiSante, K.J.; Stranzl, E.; Kazanjian, J.A.; Bowen, P.; Matsuyama, T.; Gabas, N. Graphical comparison of image analysis and laser diffraction particle size data for nonspherical particles. AAPS PharmSciTech 2006, 7, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mirahmadi, K.; Kabir, M.M.; Jeihanipour, A.; Karimi, K.; Taherzadeh, M.J. Alkaline pretreatment of spruce and birch to improve bioethanol and biogas production. BioResources 2010, 5, 928–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.Y.; Shin, S.J. Impact of alkali pretreatment on enzymatic hydrolysis of cork oak (Quercus variabilis). J. Korea TAPPI 2014, 46, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharehkhani, S.; Sadeghinezhad, E.; Kazi, S.N.; Yarmand, H.; Badarudin, A.; Safaei, M.R.; Zubir, M.N.M. Effects of pulp refining on fiber properties: A review. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015, 115, 785–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solhi, L.; Guccini, V.; Heise, K.; Solala, I.; Niinivaara, E.; Xu, W.; Kontturi, E. Nanocellulose–water interactions: Turning a detriment into an asset. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123, 1925–2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Kulachenko, A.; Mathew, A.P.; Stoltz, R.B.; Sevastyanova, O. Strength and flexibility enhancement of microfibrillated cellulose films from lignin-rich kraft pulp. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 16793–16805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maitra, J.; Shukla, V.K. Cross-linking in hydrogels: A review. Am. J. Polym. Sci. 2014, 4, 25–31. [Google Scholar]

- do Nascimento, R.A.; Uchida, D.T.; Balbinot, R.B.; Nakamura, C.V.; Uesu, N.Y.; Reis, A.V.; Bruschi, M.L. Effect of glycerol diglycidyl ether crosslinker on pectin–starch pharmaceutical films. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 307, 142257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alavarse, A.C.; Frachini, E.C.G.; da Silva, R.L.C.G.; Lima, V.H.; Shavandi, A.; Petri, D.F.S. Crosslinkers for polysaccharides and proteins: Mechanisms and efficiency. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 202, 558–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De France, K.J.; Hoare, T.; Cranston, E.D. Hydrogels and aerogels containing nanocellulose: A review. Chem. Mater. 2017, 29, 4609–4631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Fiber Length (μm) | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean | Standard Deviation | |

| OP | 0.752 | 0.308 |

| KOP | 0.159 | 0.120 |

| BKOP | 0.153 | 0.114 |

| LMFC | 0.062 | 0.036 |

| ECNF | 0.023 | 0.010 |

| Sample | Arithmetic Length (mm) | Weighted Length (mm) * | Fiber Width (μm) | Fine Content (%) | Coarseness (mg/m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OP | 0.43 | 1.39 | 33.93 | 49.1 | 0.292 |

| KOP | 0.24 | 0.86 | 29.26 | 67.6 | 0.147 |

| BKOP | 0.23 | 0.84 | 28.88 | 68.2 | 0.120 |

| Particle Size (μm) | Sample | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| KOP | LMFC | ECNF | |

| 0–100 | 47.3 | 87.4 | 98.9 |

| 101–300 | 28.4 | 10.0 | 0.4 |

| 301–800 | 19.8 | 2.3 | 0.5 |

| 801–1050 | 4.4 | 0.3 | 0.2 |

| Sample | Klason Lignin (%) |

|---|---|

| OP | 24.3 ± 0.4 |

| KOP | 18.0 ± 0.1 |

| BKOP | 3.9 ± 0.4 |

| LMFC | 21.7 ± 0.2 |

| ECNF | 0.1 ± 0.0 |

| Sample | OP | KOP | ECNF |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surface area (m2/g) | 4.5 | 7.2 | 8.4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Choi, S.R.; Lee, J.M. Fabrication and Characterization of Lignocellulose-Based Porous Materials via Chemical Crosslinking. Gels 2026, 12, 140. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12020140

Choi SR, Lee JM. Fabrication and Characterization of Lignocellulose-Based Porous Materials via Chemical Crosslinking. Gels. 2026; 12(2):140. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12020140

Chicago/Turabian StyleChoi, Sa Rang, and Jung Myoung Lee. 2026. "Fabrication and Characterization of Lignocellulose-Based Porous Materials via Chemical Crosslinking" Gels 12, no. 2: 140. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12020140

APA StyleChoi, S. R., & Lee, J. M. (2026). Fabrication and Characterization of Lignocellulose-Based Porous Materials via Chemical Crosslinking. Gels, 12(2), 140. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12020140