Thermo-Oxidative Stability and Functional Properties of Extra Virgin Olive Oil Oleogels

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Heating Treatment and Fatty Acid Profile

2.2. Antioxidant Capacity

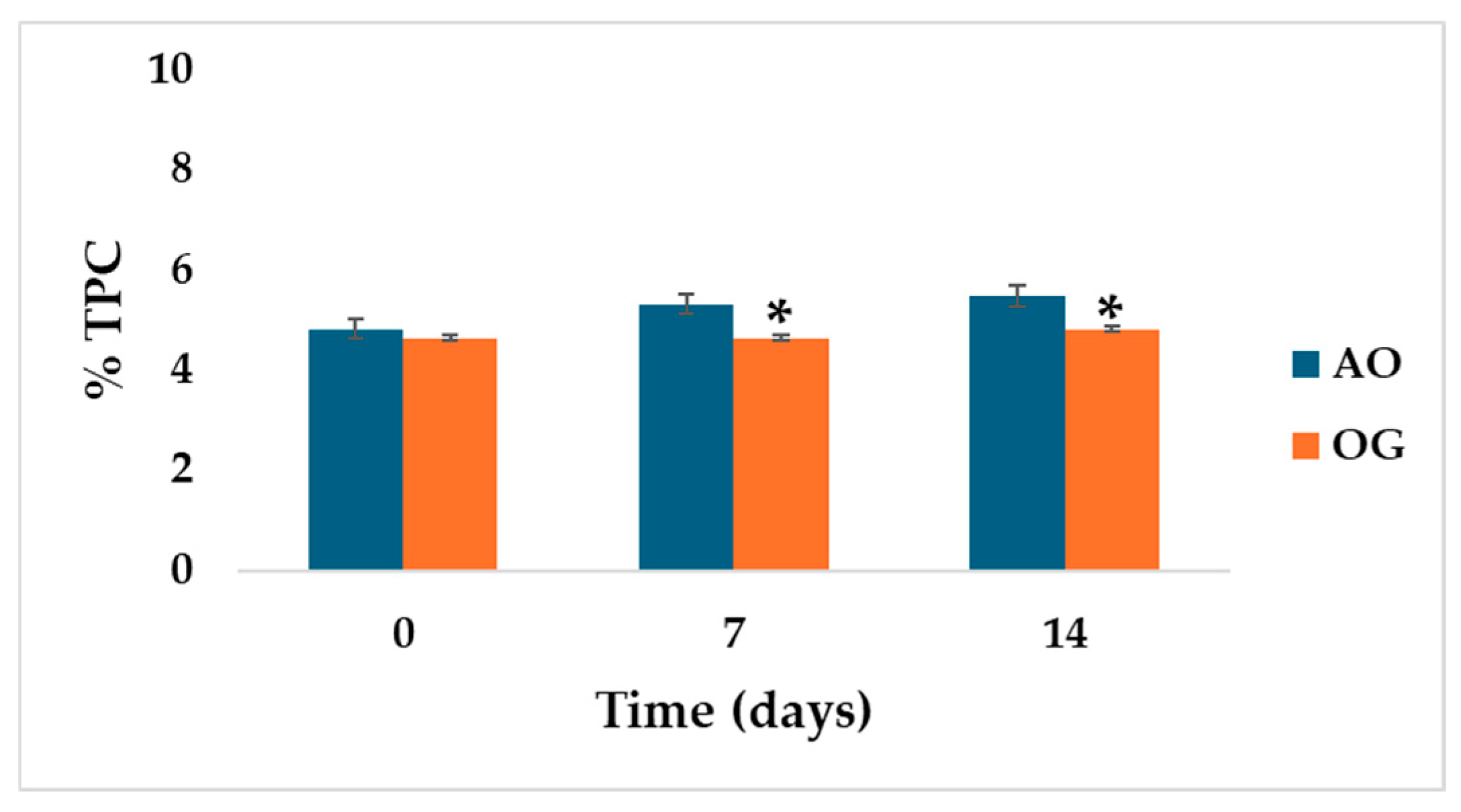

2.3. Total Polar Compounds Changes During Thermal Treatment

2.4. Acidity Index Changes During Thermal Treatment

2.5. Refractive Index (RI) Changes During Thermal Treatment

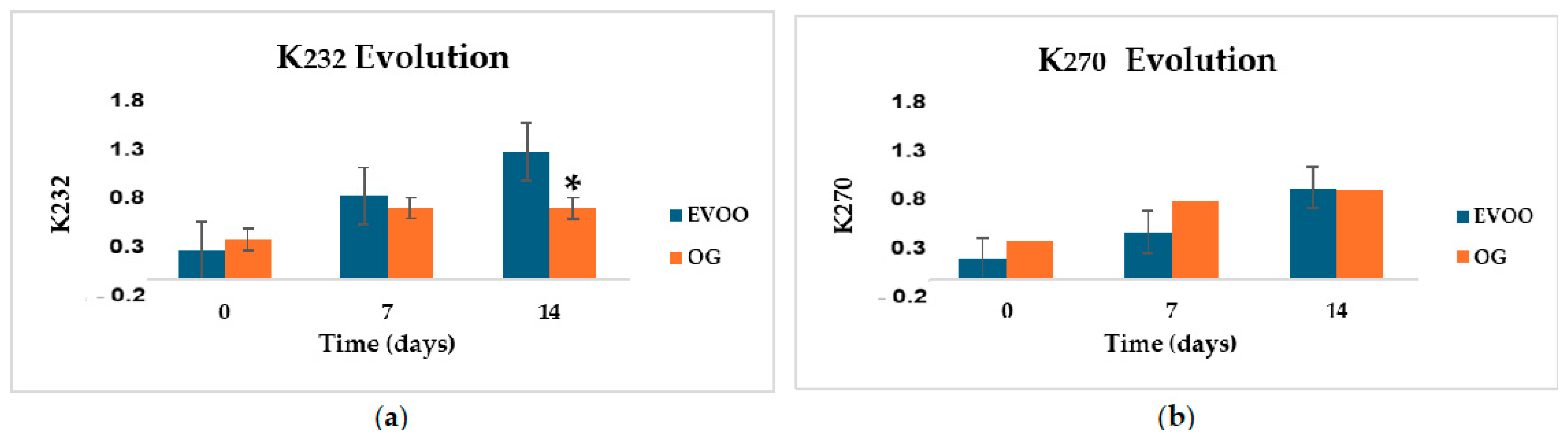

2.6. UV Absorption Coefficients (K232 and K270) Changes During Thermal Treatment

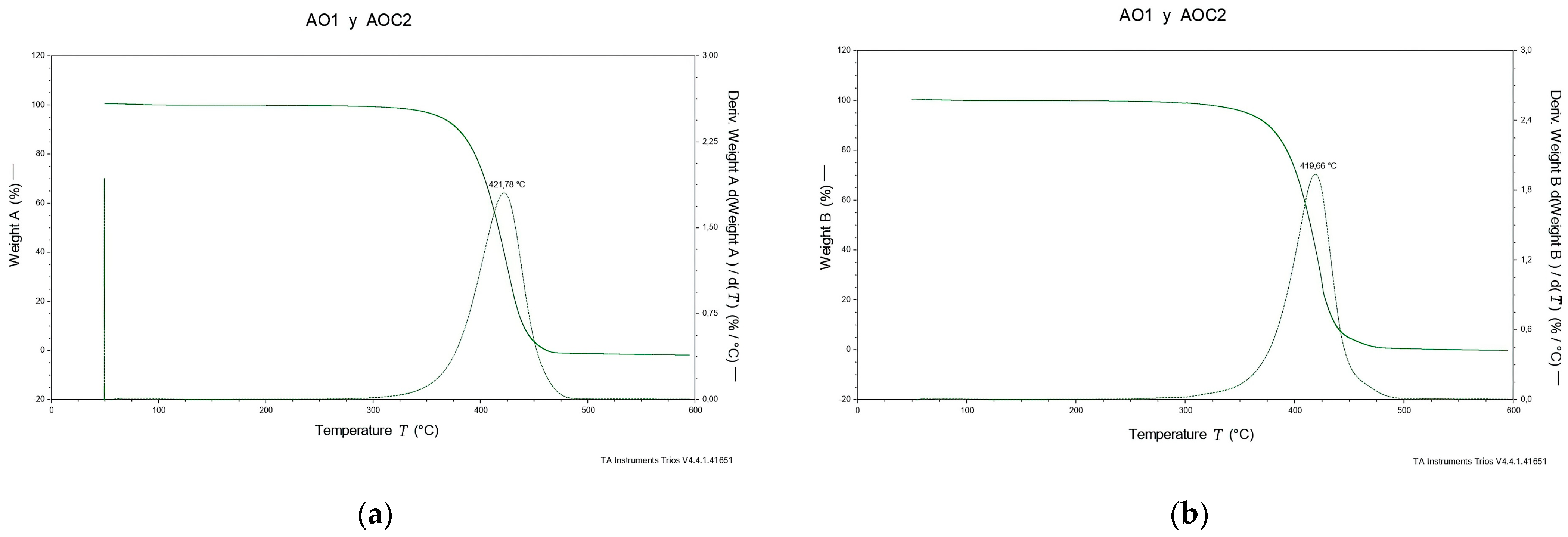

2.7. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA/DTG)

2.8. Texture Profile Analysis (TPA)

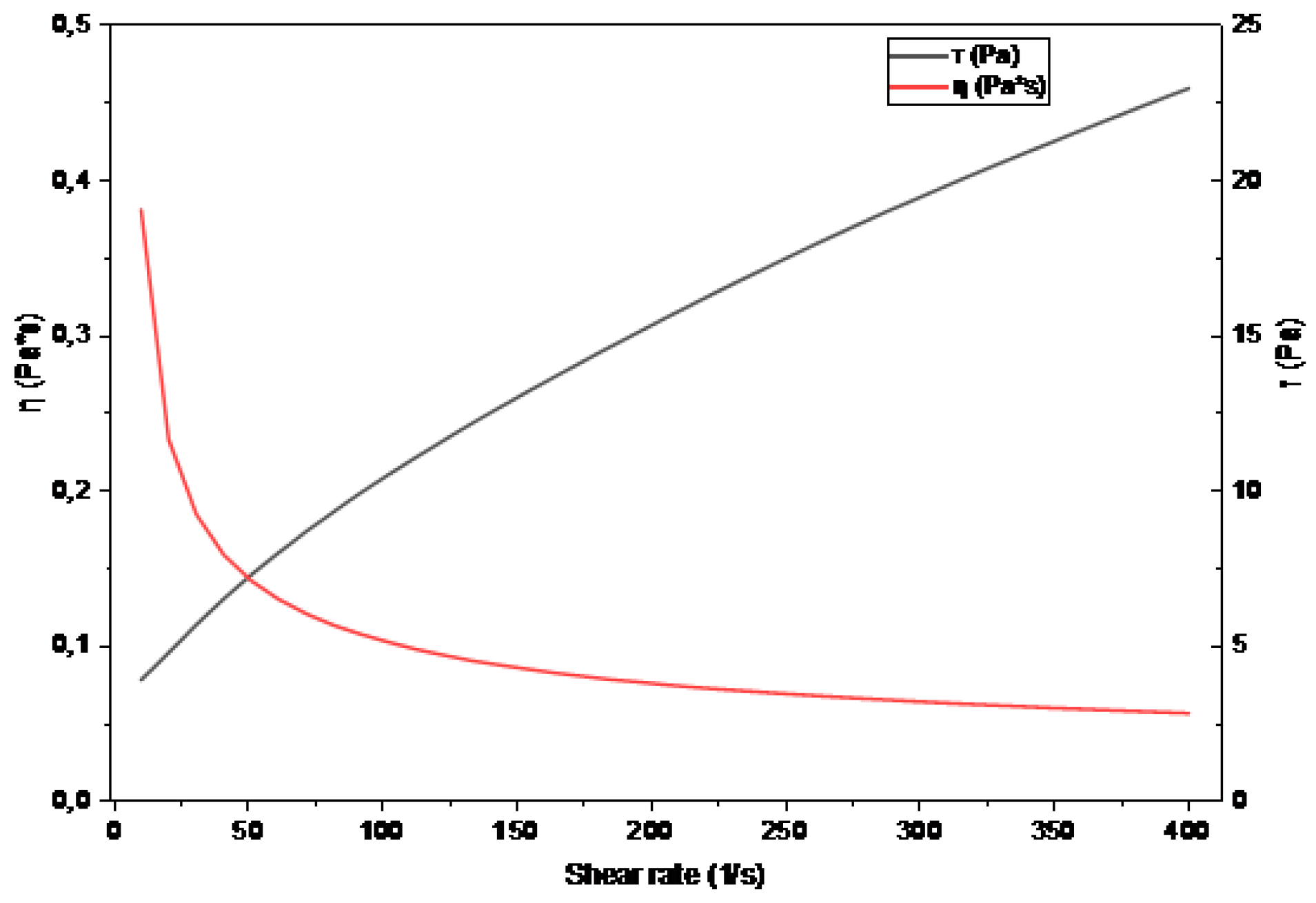

2.9. Rheological Behavior

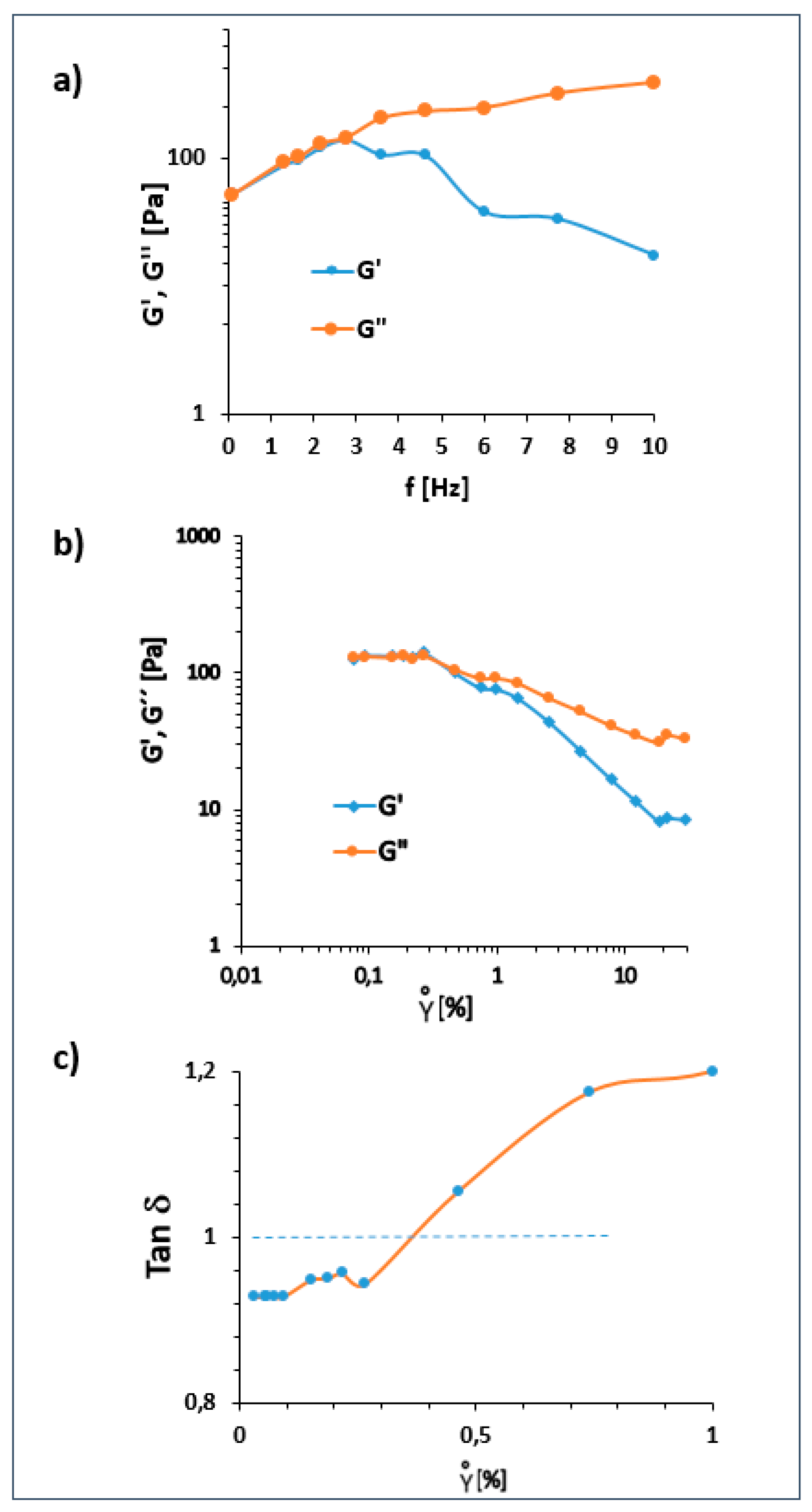

2.10. Dynamic Rheology

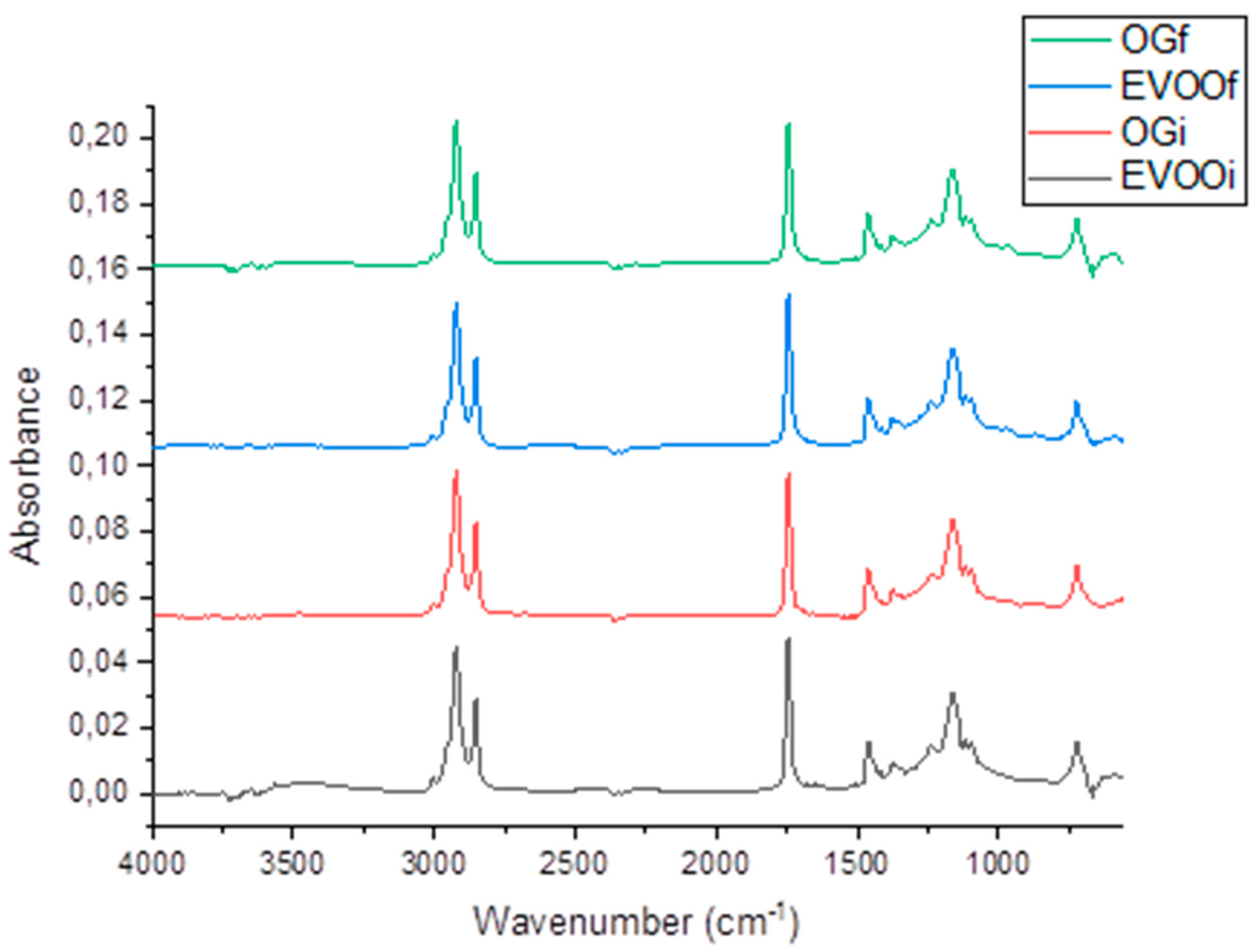

2.11. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy Analysis with Attenuated Total Reflectance (FTIR-ATR)

3. Conclusions

4. Materials and Methods

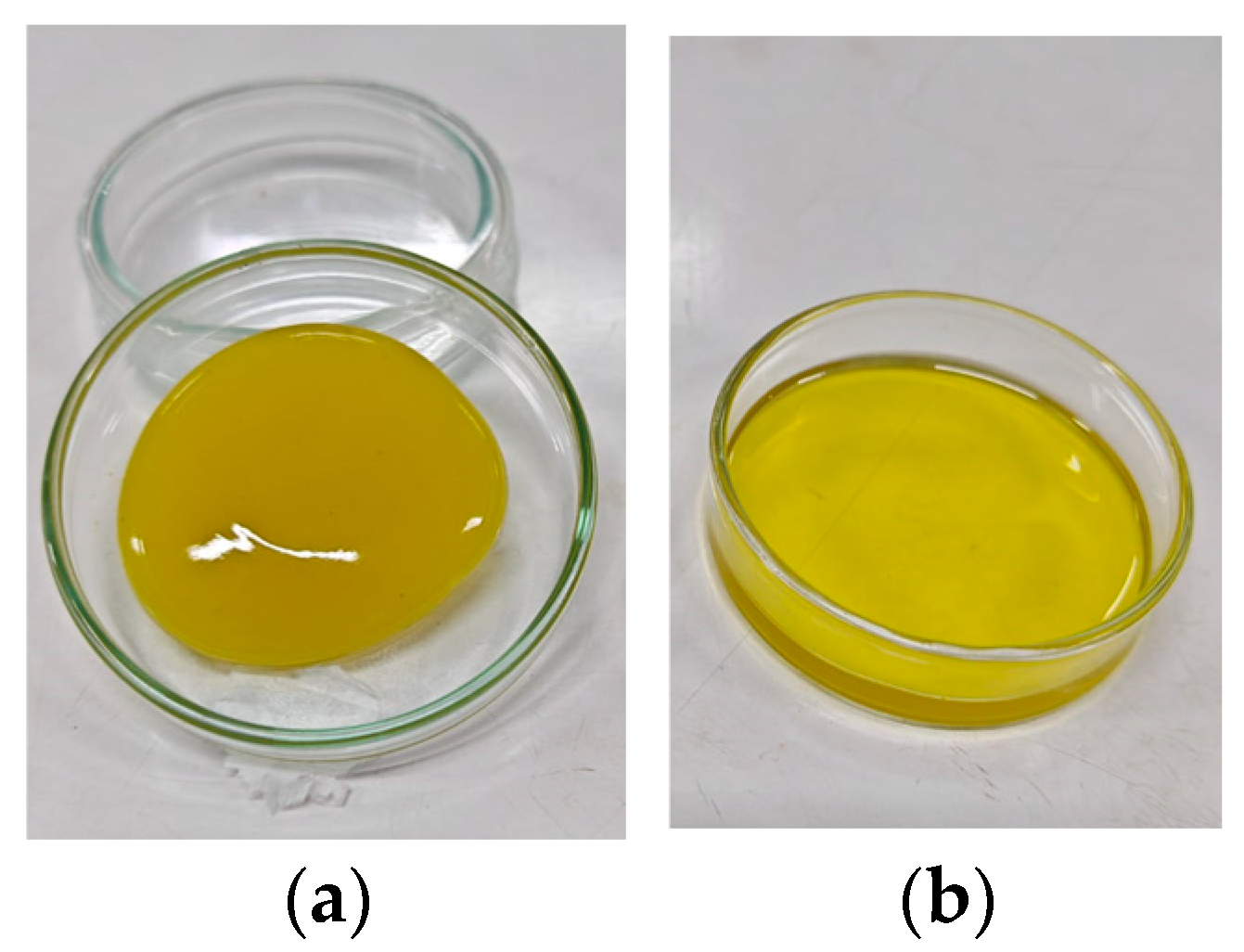

4.1. Oleogel Preparation

4.2. Thermal Process, Experimental Design and Data Analysis

4.2.1. Thermal Process

4.2.2. Fatty Acid Composition (GC-FID)

4.2.3. Oxygen Radical Absorbance Capacity (ORAC) Method

4.2.4. Total Polar Compounds and Acidity Index (AI)

4.2.5. Refractive Index

4.2.6. UV Absorption Coefficients (K232 and K270)

4.2.7. Thermogravimetric Analysis

4.2.8. Textural Characteristics

4.2.9. Rheological Measurements

Steady Shear Rheology

4.2.10. Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy with Attenuated Total Reflectance (FTIR-ATR) of Initial and Final EVOO and OG

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Acidity Index |

| AAPH | 2,2′-Azobis(2-amidinopropane) dihydrochloride |

| ATR | Attenuated Total Reflectance |

| BW | Beeswax |

| DTG | Derivative Thermogravimetry |

| EVOO | Extra Virgin Olive Oil |

| FAMEs | Fatty Acid Methyl Esters |

| FTIR | Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy |

| GC-FID | Gas Chromatography with Flame Ionization Detection |

| G′ | Storage Modulus |

| G″ | Loss Modulus |

| G* | Complex Modulus |

| K232 | Specific Extinction Coefficient at 232 nm |

| K270 | Specific Extinction Coefficient at 270 nm |

| LVR | Linear Viscoelastic Region |

| MUFA | Monounsaturated Fatty Acids |

| OG | Oleogel |

| ORAC | Oxygen Radical Absorbance Capacity |

| PUFA | Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids |

| RI | Refractive Index |

| SD | Standar deviation |

| SFA | Saturated Fatty Acids |

| TGA | Thermogravimetric Analysis |

| Tmax | Temperature of Maximum Degradation Rate |

| Tonset | Onset Temperature of Thermal Degradation |

| TPC | Total Polar Compounds |

| TPA | Texture Profile Analysis |

| UV | Ultraviolet |

References

- Félix, R.; Valentão, P.; Andrade, P.; Félix, C.; Novais, S.; Lemos, M. Evaluating the In Vitro Potential of Natural Extracts to Protect Lipids from Oxidative Damage. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valgimigli, L. Lipid Peroxidation and Antioxidant Protection. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Xiao, H.; Lyu, X.; Chen, H.; Wei, F. Lipid oxidation in food science and nutritional health: A comprehensive review. Oil Crop Sci. 2023, 8, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrero, A.D.; Quesada, A.R.; Martínez-Poveda, B.; Medina, M.Á. Anti-Cancer, Anti-Angiogenic, and Anti-Atherogenic Potential of Key Phenolic Compounds from Virgin Olive Oil. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, M.; Vale, N.; Silva, P. Neuroprotective Effects of Olive Oil: A Comprehensive Review of Antioxidant Properties. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsimihodimos, V.; Psoma, O. Extra Virgin Olive Oil and Metabolic Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 8117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, M.; Vergara, C.E.; Forero-Doria, O.; Guzmán, L.; Perez-Camino, M.C. Chemical evaluation and thermal behavior of Chilean hazelnut oil (Gevuina avellana Mol): A comparative study with extra virgin olive oil. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2019, 245, 1021–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, J.C.O.; Dos Santos, I.M.G.; de Souza, A.G.; Prasad, S.; Dos Santos, A.V. Thermal stability and kinetic study on thermal decomposition of commercial edible oils by thermogravimetry. J. Food Sci. 2002, 67, 1393–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, M.; Reyes-García, L.; Ortiz-Viedma, J.; Romero, N.; Vilcanqui, Y.; Rogel, C.; Echeverría, J.; Forero-Doria, O. Thermal Behavior Improvement of Fortified Commercial Avocado (Persea americana Mill.) Oil with Maqui (Aristotelia chilensis) Leaf Extracts. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García, M.F.; Vergara, C.; Ortiz-Viedma, J.; Prieto, J.; Concha-Meyer, A. Use of culinary ingredients as protective components during thermal heating of pumpkin oil. Food Chem. X 2025, 26, 102272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhouri, M.; Ghnimi, H.; Amri, Z.; Koubaa, N.; Hammami, M. Effect of tunisian pomegranate peel extract on the oxidative stability of corn oil under heating conditions. Grasas Aceites 2022, 73, e449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, N.; Ghavami, M.; Rashidi, L.; Gharachorloo, M.; Nateghi, L. Effects of adding green tea extract on the oxidative stability and shelf life of sunflower oil during storage. Food Chem. X 2024, 21, 101168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, C.M.; Barbut, S.; Marangoni, A.G. Edible oleogels for the oral delivery of lipid soluble molecules: Composition and structural design considerations. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 57, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Prakash, B.; Shi, Y. Synthesizing lignin-based gelators to prepare oleogels used as green and fossil-free greases. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 305, 141074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dassanayake, L.S.K.; Kodali, D.R.; Ueno, S.; Sato, K. Physical properties of rice bran wax in bulk and organogels. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2009, 86, 1163–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Liu, G.; Bogojevic, O.; Pedersen, J.N.; Guo, Z. Edible oleogels as solid fat alternatives: Composition and oleogelation mechanism implications. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2022, 21, 2077–2104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saw, M.H.; Lim, W.H.; Yeoh, C.B.; Hishamuddin, E.; Kanagaratnam, S.; Mohd Hassim, N.; Ismail, N.H.; Tan, C.P. Effects of storage temperature and duration on physical and microstructure properties of superolein oleogels. Grasas Aceites 2024, 75, 2198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Jo, Y.J.; Lee, S.H.; Park, S.H. Development of Oleogel-Based Fat Replacer and Its Application in Pan Bread Making. Foods 2024, 13, 1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamali, E.; Sahari, M.A.; Barzegar, M.; Gavlighi, H.A. Effect of transesterified amaranth oil oleogel as a cocoa butter replacer on the physicochemical properties of dark chocolate. Food Chem. X 2025, 26, 102305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, L.T.; Glomm, W.R.; Molesworth, P.P. Fish Oil Oleogels with Wax and Fatty Acid Gelators: Effects on Microstructure, Thermal Behaviour, Viscosity, and Oxidative Stability. Gels 2025, 11, 723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igenbayev, A.; Kakimov, M.; Mursalykova, M.; Wieczorek, B.; Gajdzik, B.; Wolniak, R.; Dzienniak, D.; Bembenek, M. Effect of Using Oleogel on the Physicochemical Properties, Sensory Characteristics, and Fatty Acid Composition of Meat Patties. Foods 2024, 13, 3849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naves, B.V.B.; Silva, T.L.T.D.; Nunes, C.A.; Haddad, F.F.; Bastos, S.C. Development, Characterization, and Stability of Margarine Containing Oleogels Based on Olive Oil, Coconut Oil, Starch, and Beeswax. Gels 2025, 11, 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzoor, S.; Masoodi, F.; Naqash, F.; Rashid, R. Oleogels: Promising alternatives to solid fats for food applications. Food Hydrocoll. Health 2022, 2, 100058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrca, I.; Mikrut, A.; Fredotović, Ž.; Akrap, K.; Kremer, D.; Orhanović, S.; Bačić, K.; Dunkić, V.; Nazlić, M. Genus Veronica—Antioxidant, Cytotoxic and Antibacterial Activity of Phenolic Compounds from Wild and Cultivated Species. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antileo-Laurie, J.; Olate-Olave, V.; Fehrmann-Riquelme, V.; Anabalón-Alvarez, C.; Cid-Carrillo, L.; Campanini-Salinas, J.; Fernández-Galleguillos, C.; Quesada-Romero, L. Natural Deep Eutectic Solvent (NaDES) Extraction, HPLC-DAD Analysis, and Antioxidant Activity of Chilean Ugni molinae Turcz. Fruits. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Millao, S.; Quilaqueo, M.; Contardo, I.; Rubilar, M. Enhancing the Oxidative Stability of Beeswax–Canola Oleogels: Effects of Ascorbic Acid and Alpha-Tocopherol on Their Physical and Chemical Properties. Gels 2025, 11, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.; Zulkurnain, M. Ultrasonic-Assisted Ginkgo biloba Leaves Extract as Natural Antioxidant on Oxidative Stability of Oils During Deep-Frying. Foods 2025, 14, 2958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of Spain. Norma de calidad para los aceites y grasas calentados. Boletín Of. Estado (BOE) 1989, 26, 2665–2667. [Google Scholar]

- Dobarganes, M.C.; Márquez-Ruiz, G. Regulation of used frying fats and validity of quick tests for discarding the fats. Grasas Aceites 1998, 49, 331–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhang, L.; Guo, X.; Qiang, J.; Cao, Y.; Zhang, S.; Yu, X. Influence of frying conditions on quality attributes of frying oils: Kinetic investigation of polar compounds. Food Chem. X 2025, 29, 102673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Torres, S.; González-Casado, A.; Medina-García, M.; Medina-Vázquez, M.S.; Cuadros-Rodríguez, L. A Comparison of the Stability of Refined Edible Vegetable Oils under Frying Conditions: Multivariate Fingerprinting Approach. Foods 2023, 12, 604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aydınkaptan, E.; Mazi, I.B. Monitoring the physicochemical features of sunflower oil and French fries during repeated microwave frying and deep-fat frying. Grasas Aceites 2017, 68, e202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salaj, N.; Kladar, N.; Čonić, B.S.; Jeremić, K.; Barjaktarović, K.; Hitl, M.; Gavarić, N.; Božin, B. Stabilization of sunflower and olive oils with savory (Satureja kitaibelii, Lamiaceae). J. Food Nutr. Res. 2020, 59, 259–271. Available online: https://www.cabidigitallibrary.org/doi/pdf/10.5555/20203429366 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Li, P.; Yang, X.; Lee, W.J.; Huang, F.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y. Comparison between synthetic and rosemary-based antioxidants for the deep frying of French fries in refined soybean oils evaluated by chemical and non-destructive rapid methods. Food Chem. 2021, 335, 127638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nid Ahmed, M.; Abourat, K.; Gagour, J.; Sakar, E.H.; Majourhat, K.; Koubachi, J.; Gharby, S. Valorization of saffron (Crocus sativus L.) stigma as a potential natural antioxidant for soybean (Glycine max L.) oil stabilization. Heliyon 2024, 10, e25875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd-El-hady, M.A.M. Evaluation of phenolic extracts from red onion scale and potato peel as antioxidants on shelf life of soybean and sunflower oils. Sciences. 2018, 8, 579–1598. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, W.; Yu, L.; Wei, Z. Crystallization Kinetics of Oleogels Prepared with Essential Oils from Thirteen Spices. Foods 2025, 14, 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forero-Doria, O.; Flores García, M.; Vergara, C.E.; Guzmán, L. Thermal analysis and antioxidant activity of oil extracted from pulp of ripe avocados. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2017, 130, 959–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotirova, Y.; Gugleva, V.; Stoeva, S.; Kolev, I.; Nikolova, R.; Marudova, M.; Nikolova, K.; Kiselova-Kaneva, Y.; Hristova, M.; Andonova, V. Bigel Formulations of Nanoencapsulated St. John’s Wort Extract-An Approach for Enhanced Wound Healing. Gels 2023, 9, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, Y.B.; Yusri, A.S.; Sarbon, N.M. Effect of gelling agents on the techno-functional, collagen bioavailability and phytochemical properties of botanic gummy jelly containing marine hydrolyzed collagen. Food Chem. Adv. 2025, 6, 100915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Ge, Z.; Zhang, L.; Zong, W.; Fan, W. Bigels based on myofibrillar protein hydrogel and beeswax oleogel: Micromorphology, mechanical property, and rheological properties. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 309, 142962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abedi, E.; Altemimi, A.B.; Roohi, R.; Hashemi, S.M.B. Understanding Starch Gelatinization, Thermodynamic Properties, and Rheology Modeling of Tapioca Starch–Polyol Blends Under Pre- and Post-ultrasonication. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2025, 18, 2985–3001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Ma, X.; Zhang, L.; Xu, X.; Cheng, S.; Du, M. Construction of thermotable and temperature-responsive emulsion gels using gelatin: A novel strategy for replacing animal fat. Food Hydrocoll. 2025, 158, 110529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yang, H.; Zhang, G.; Yan, X.; Han, J.; Cao, X.; Xu, Y.; Fan, Z. Rheological and Thermal Properties of Salecan/Sanxan Composite Hydrogels for Food and Biomedical Applications. Gels 2025, 11, 839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, A.A.; Aiello, I.; Oliviero Rossi, C.; Caputo, P. Oleogels: Uses, Applications, and Potential in the Food Industry. Gels 2025, 11, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scholten, E. Edible oleogels: How suitable are proteins as a structurant? Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2019, 27, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Sun, R.; Zeng, X.; Zhang, J.; Xing, R.; Sun, C.; Chen, Y. Rapid Classification and Quantification of Camellia (Camellia oleifera Abel.) Oil Blended with Rapeseed Oil Using FTIR-ATR Spectroscopy. Molecules 2020, 25, 2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, M.; Vergara, C.; Toledo-Aquino, T.; Ortiz-Viedma, J.; Barros-Velázquez, J. Quality parameters during deep frying of avocado oil and olive oil. Qual. Assur. Saf. Crops Foods 2024, 16, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ankaraligil, P.; Aydeniz Güneşer, B. Oleogel-based frying medium: Influence of rice bran wax-canola oil oleogel on volatile profile in fried fish fillets. Discov. Food 2024, 4, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.; Yang, L.; Li, X.; Tang, H.; Li, X.; Xue, Y.; Duan, Z. Antioxidant Efficacy of Rosemary Extract in Improving the Oxidative Stability of Rapeseed Oil during Storage. Foods 2023, 12, 3583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cert, A.; Moreda, W.; Pérez-Camino, M.C. Methods of preparation of fatty acid methyl esters (FAME) and their determination by gas chromatography. Grasas Aceites 2000, 51, 447–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orsavova, J.; Misurcova, L.; Ambrozova, J.V.; Vicha, R.; Mlcek, J. Fatty Acids Composition of Vegetable Oils and Its Contribution to Dietary Energy Intake and Dependence of Cardiovascular Mortality on Dietary Intake of Fatty Acids. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 12871–12890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, D.; Ou, B.; Hampsch-Woodill, M.; Flanagan, J.A.; Deemer, E.K. Development and Validation of Oxygen Radical Absorbance Capacity Assay for Lipophilic Antioxidants Using Randomly Methylated β-Cyclodextrin as the Solubility Enhancer. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 1815–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prior, R.L.; Hoang, H.; Gu, L.; Wu, X.; Bacchiocca, M.; Howard, L.; Hampsch-Woodill, M.; Huang, D.; Ou, B.; Jacob, R. Assays for Hydrophilic and Lipophilic Antioxidant Capacity (oxygen radical absorbance capacity (ORACFL)) of Plasma and Other Biological and Food Samples. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 3273–3279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paz Antolín, I.; Molero Meneses, M. Application of UV-visible spectrophotometry to study of the thermal stability of edible vegetable oils. Grasas Aceites 2000, 51, 424–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, R.I.; Muñoz-Vera, M.; Morales-Quintana, L. Evaluation of Cell Wall Modification in Two Strawberry Cultivars with Contrasted Softness. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriele, D.; de Cindio, B.; D’Antona, P.A. A weak Gel Model for Foods. Rheol. Acta 2001, 40, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Fatty Acid | EVOO i (%) | EVOO f (%) | p-Value | OG i (%) | OG f (%) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Myristic acid (C14:0) | 0.012 ± <0.01 | 0.01 ± <0.01 | 0.069 | 0.01 ± <0.01 | 0.01 ± <0.01 | 0.02 |

| Pentadecanoic acid (C15:0) | 0.01 ± <0.01 | 0.01 ± <0.01 | 0.1 | 0.01 ± <0.01 | 0.02 ± 0.02 | 0.04 |

| Palmitic acid (C16:0) | 14.79 ± 0.08 | 15.61 ± 0.27 | 0.018 | 14.40 ± 0.43 | 15.95 ± 0.28 | 0.015 |

| Palmitoleic acid (C16:1) | 0.84 ± 0.01 | 0.84 ± 0.01 | 0.4 | 0.81 ± 0.05 | 0.84 ± 0.02 | 0.27 |

| Heptadecanoic acid (C17:0) | 0.14 ± 0.01 | 0.15 ± <0.01 | 0.055 | 0.15 ± <0.01 | 0.16 ± <0.01 | 0.06 |

| cis-10-Heptadecenoic acid (C17:1) | 1<D.L. 1 | 1<D.L. 1 | - | 0.27 ± 0.02 | 0.14 ± 0.06 | 0.03 |

| Stearic acid (C18:0) | 2.03 ± 0.03 | 2.22 ± 0.03 | 0.005 | 1.99 ± 0.04 | 2.24 ± 0.04 | 0.003 |

| Oleic acid (C18:1 cis n9) | 73.75 ± 0.14 | 75.65 ± 0.44 | 0.004 | 74.07 ± 0.37 | 75.41 ± 0.43 | 0.02 |

| Linoleic acid (C18:2 trans n6) | 7.27 ± 0.09 | 4.65 ± 0.34 | 0.004 | 7.39 ± 0.05 | 4.06 ± 0.10 | <0.001 |

| Arachidic acid (C20:0) | 0.31 ± 0.02 | 0.35 ± 0.01 | 0.003 | 0.31 ± 0.01 | 0.37 ± 0.03 | 0.018 |

| cis-11-Eicosenoic acid (C20:1) | 0.69 ± 0.02 | 0.41 ± 0.03 | 0.004 | 0.50 ± 0.01 | 0.37 ± <0.01 | <0.001 |

| Behenic acid (C21:0) | 0.15 ± 0.07 | 0.10 ± <0.01 | 0.16 | 0.09 ± 0.01 | 0.43 ± 0.02 | <0.001 |

| Time (Days) | EVOO | OG | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1.4674 ± 0.0013 | 1.4631 ± 0.0015 | 0.001 |

| 7 | 1.4667 ± 0.0021 | 1.4629 ± 0.0009 | 0.04 |

| 14 | 1.4676 ± 0.0002 | 1.4642 ± 0.0035 | 0.12 |

| Model | τ0 | Ƞp | ƞ | K | N | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Newton | - | - | 0.067 ± 0.016 | - | - | 0.7634 |

| Bingham | 5.049 ± 0.562 | 0.048 ± 0.019 | - | - | - | 0.9800 |

| Ostwald de Waele | - | - | - | 0.832 ± 0.160 | 0.558 ± 0.054 | 0.9942 |

| Casson (lin) | 2.272 ± 0.216 | 0.029 ± 0.013 | - | - | - | 0.9963 |

| Herschel–Bulkley | 1.902 ± 0.148 | - | - | 0.415 ± 0.168 | 0.665 ± 0.031 | 0.9997 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Bascuñan, D.; Vergara, C.; Valdes, C.; Mirabal, Y.; Quiroz, R.; Ortiz-Viedma, J.; Barros, V.; Vargas, J.; Flores, M. Thermo-Oxidative Stability and Functional Properties of Extra Virgin Olive Oil Oleogels. Gels 2026, 12, 116. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12020116

Bascuñan D, Vergara C, Valdes C, Mirabal Y, Quiroz R, Ortiz-Viedma J, Barros V, Vargas J, Flores M. Thermo-Oxidative Stability and Functional Properties of Extra Virgin Olive Oil Oleogels. Gels. 2026; 12(2):116. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12020116

Chicago/Turabian StyleBascuñan, Denisse, Claudia Vergara, Cristian Valdes, Yaneris Mirabal, Roberto Quiroz, Jaime Ortiz-Viedma, Vicente Barros, Jaime Vargas, and Marcos Flores. 2026. "Thermo-Oxidative Stability and Functional Properties of Extra Virgin Olive Oil Oleogels" Gels 12, no. 2: 116. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12020116

APA StyleBascuñan, D., Vergara, C., Valdes, C., Mirabal, Y., Quiroz, R., Ortiz-Viedma, J., Barros, V., Vargas, J., & Flores, M. (2026). Thermo-Oxidative Stability and Functional Properties of Extra Virgin Olive Oil Oleogels. Gels, 12(2), 116. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12020116