Comparative Analysis of Physicochemical Properties and Biocompatibility of Biomass-Derived and Fossil-Derived Polyvinyl Alcohol Hydrogels: Material Screening for Wound Dressing Applications

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

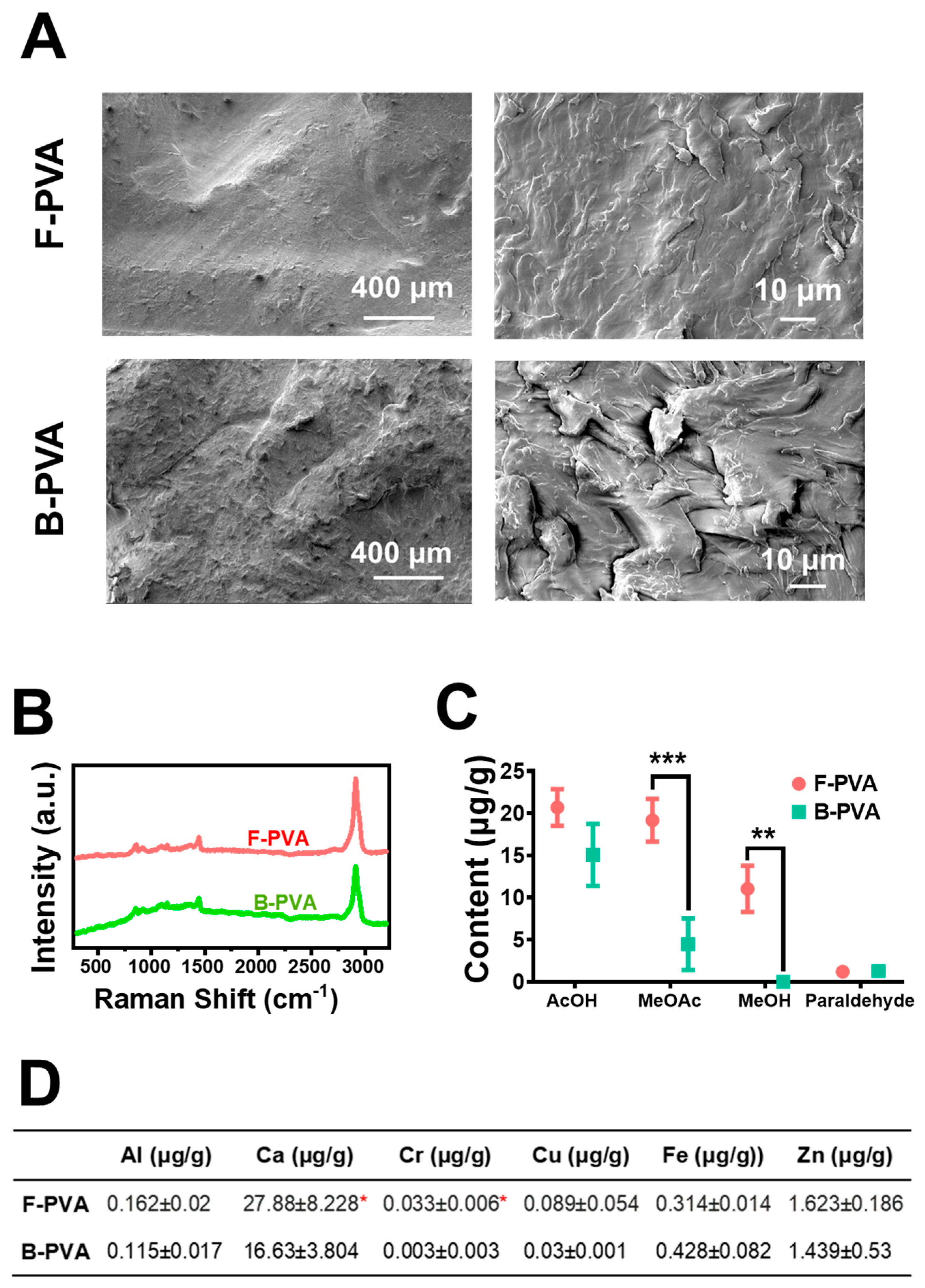

2.1. Physicochemical Characterization of Fossil-Derived and Biomass-Derived PVA and Their Hydrogels

2.2. Biocompatibility of Fossil-Derived and Biomass-Derived PVA and Their Hydrogels

2.3. Optical Transmittance, Swelling and Adhesion Capacities of Fossil-Derived and Biomass-Derived PVA Hydrogels

2.4. Drug Loading and Controlled Release Performance of Fossil-Derived and Biomass-Derived PVA Hydrogels

3. Conclusions

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

4.2. Preparation of PVA Aqueous Solutions and PVA Hydrogels

4.3. Characterization of Fossil-Derived and Biomass-Derived PVA Materials and Hydrogels

4.4. Cell Culture and Exposure

4.4.1. Cell Culture

4.4.2. Exposure of Cells to PVA Raw Materials

4.4.3. Exposure of Cells to PVA Hydrogels

4.5. Evaluation of the Cytotoxicity of PVA

4.6. Inflammatory Cytokines Determination

4.7. Optical Transparency Measurement

4.8. Swelling Capacity Measurement

4.9. Adhesion Assessment

4.10. Drug Loading and Drug Sustained-Release Experiments

4.11. Statistical Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Varaprasad, K.; Raghavendra, G.M.; Jayaramudu, T.; Yallapu, M.M.; Sadiku, R. A mini review on hydrogels classification and recent developments in miscellaneous applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2017, 79, 958–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IMARC. Polyvinyl Alcohol (PVA) Market Report by Grade (Fully Hydrolyzed, Partially Hydrolyzed, Sub-Partially Hydrolyzed, Low Foaming Grades, and Others), End Use Industry (Paper, Food Packaging, Construction, Electronics, and Others), and Region 2025–2033; IMARC Services Pvt. Ltd.: London, UK, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, X.; Gao, W.; Shi, H. Research and Industrialization of Process Routes for Biomass-Based Polyvinyl Alcohol Production. Anhui Chem. Ind. 2016, 42, 67–69+75. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y. Analysis of Environmental Impact of Ethylene Production Based on Life Cycle Approach. Master’s Thesis, Dalian University of Technology, Dalian, China, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, R.; Sartape, R.; Minocha, N.; Goyal, I.; Singh, M.R. Advancements in environmentally sustainable technologies for ethylene production. Energy Fuels 2023, 37, 12589–12622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanta, M.; Fahey, D.; Subramaniam, B. Environmental impacts of ethylene production from diverse feedstocks and energy sources. Appl. Petrochem. Res. 2014, 4, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Lin, Q.; Yu, H.; Shao, L.; Cui, X.; Pang, Q.; Hou, R. Construction methods and biomedical applications of PVA-based hydrogels. Front. Chem. 2024, 12, 1376799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xi, Y.; Hu, L.; Chen, X.; Zuo, L.; Bai, X.; Du, W.; Xu, N. Antibacterial and Anti-Inflammatory Polysaccharide from Fructus Ligustri Lucidi Incorporated in PVA/Pectin Hydrogels Accelerate Wound Healing. Molecules 2024, 29, 1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baghaie, S.; Khorasani, M.T.; Zarrabi, A.; Moshtaghian, J. Wound healing properties of PVA/starch/chitosan hydrogel membranes with nano Zinc oxide as antibacterial wound dressing material. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 2017, 28, 2220–2241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulubayram, K.; Cakar, A.N.; Korkusuz, P.; Ertan, C.; Hasirci, N. EGF containing gelatin-based wound dressings. Biomaterials 2001, 22, 1345–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Carvalho, R.A.; Grosso, C.R.F. Characterization of gelatin based films modified with transglutaminase, lyoxal and formaldehyde. Food Hydrocoll. 2004, 18, 717–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, B.; Chen, W.; Yan, L. Preparation of flexible, highly transparent, cross-linked cellulose thin film with high mechanical strength and low coefficient of thermal expansion. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2013, 1, 1474–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shyna, S.; Nair, P.D.; Thomas, L.V. A nonadherent chitosan-polyvinyl alcohol absorbent wound dressing prepared via controlled freeze-dry technology. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 150, 129–140. [Google Scholar]

- Kamoun, E.A.; Chen, X.; Eldin, M.S.M.; Kenawy, E.R.S. Crosslinked poly (vinyl alcohol) hydrogels for wound dressing applications: A review of remarkably blended polymers. Arab. J. Chem. 2015, 8, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sureka, V.; Vasugi, S.; Afeeza, K.; Priya Dharshini, B.; Anandakumar, P.; Dilipan, E. Enhanced wound healing through alginate/PVA hydrogels enriched with seagrass extract: An in vivo and in vitro evaluation. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 2025, 36, 2513–2529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busuioc, C.; Lsopencu, G.O.; Deleanu, L.M. Bacterial cellulose-polyvinyl alcohol based complex composites for controlled drug release. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hago, E.E.; Li, X. Interpenetration polymer network hydrogels based on gelatin and PVA by biocompatible approaches: Synthesis and characterization. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2013, 2013, 328763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Xiao, X.; Zhang, Y.; Long, R.; Kankala, R.K.; Wang, S.; Liu, Y. Microneedles based on hyaluronic acid-polyvinyl alcohol with antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant effects promote diabetic wound healing. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 282, 137185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alipournazari, P.; Pourmadadi, M.; Abdouss, M.; Rahdar, A.; Pandey, S. Enhanced delivery of doxorubicin for breast cancer treatment using pH-sensitive starch/PVA/g-C3N4 hydrogel. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 265, 130901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Razzak, M.T.; Darmawan, D.; Zainuddin, S. Irradiation of polyvinyl alcohol and polyvinyl pyrrolidone blended hydrogel for wound dressing. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2001, 62, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, Z.; Liu, X.; Zhao, T.; Jiang, D.; Zhao, J.; Dong, X.; Ouyang, L. Self-healing Ppy-hydrogel promotes diabetic skin wound healing through enhanced sterilization and macrophage orchestration triggered by NIR. Biomaterials 2025, 315, 122964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- e Souza, I.E.P.; Barrioni, B.R.; Costa, M.C.; Miriceia, N.M.; Sachs, D.; Ribeiro, G.C.; Soares, D.C.; Pereira, M.M.; Nunes, E.H. Development OF pH-sensitive wound dressings using PVA/PAA hydrogels and bioactive glass nanoparticles doped with cerium and cobalt. Mater. Today Commun. 2024, 38, 107981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afzal, A.; Jalalah, M.; Noor, A.; Khaliq, Z.; Qadir, M.B.; Masood, R.; Nazir, A.; Ahmad, S.; Ahmad, F.; Irfan, M.; et al. Development and characterization of drug loaded PVA/PCL fibres for wound dressing applications. Polymers 2023, 15, 1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Chen, C.; Liu, K.; Tu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Li, Y. Preparation of PVA hydrogel with high-transparence and investigations of its transparent mechanism. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 24023–24030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, B.-H.; Hoek, E.M.; Yan, Y.; Subramani, A.; Huang, X.; Hurwitz, G.; Ghosh, A.K.; Jawor, A. Interfacial polymerization of thin film nanocomposites: A new concept for reverse osmosis membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 2007, 294, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, K.K.H.; Hutter, J.L.; Zinke-Allmang, M.; Wan, W. Physical properties of ion beam treated electrospun poly (vinyl alcohol) nanofibers. Eur. Polym. J. 2009, 45, 1349–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavaloiu, R.D.; Stoica-Guzun, A.; Stroescu, M.; Jinga, S.I.; Dobre, T. Composite films of poly (vinyl alcohol)–chitosan–bacterial cellulose for drug controlled release. Int. J. Biol. Macromol 2014, 68, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamoun, E.A.; Kenawy, E.R.S.; Tamer, T.M.; El-Meligy, M.A.; Eldin, M.S.M. Poly (vinyl alcohol)-alginate physically crosslinked hydrogel membranes for wound dressing applications: Characterization and bio-evaluation. Arab. J. Chem. 2015, 8, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feiz, S.; Navarchian, A.H.; Jazani, O.M. Poly (vinyl alcohol) membranes in wound-dressing application: Microstructure, physical properties, and drug release behavior. Iran. Polym. J. 2018, 27, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagarkar, R.; Patel, J. Polyvinyl alcohol: A comprehensive study. Acta Sci. Pharm. Sci. 2019, 3, 34–44. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Y.H.; Lin, C.Y.; Yeh, J.M.; Lin, W.H. Preparation and properties of poly (vinyl alcohol)–clay nanocomposite materials. Polymer 2003, 44, 3553–3560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martwong, E.; Chuetor, S.; Junthip, J. Adsorption of cationic contaminants by cyclodextrin nanosponges cross-linked with 1, 2, 3, 4-butanetetracarboxylic acid and poly (vinyl alcohol). Polymers 2022, 14, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Zhong, H.-J.; Ding, H.; Yu, B.; Ma, X.; Liu, X.; Chong, C.-M.; He, J. Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA)-based hydrogels: Recent progress in fabrication, properties, and multifunctional applications. Polymers 2024, 16, 2755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, T.; Sun, Y.; Wu, Y.; Wang, J.; Ding, Y.; Cheng, J.; Guo, M. Mechanical, microstructural, and rheological characterization of gelatin-dialdehyde starch hydrogels constructed by dual dynamic crosslinking. LWT 2022, 161, 113374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, R.; Aslam Khan, M.U.; Stojanović, G.M.; Javed, A.; Haider, S.; Abd Razak, S.I. Fabrication of bilayer nanofibrous-hydrogel scaffold from bacterial cellulose, PVA, and gelatin as advanced dressing for wound healing and soft tissue engineering. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 6527–6536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Annabi, N.; Nichol, J.W.; Zhong, X.; Ji, C.; Koshy, S.; Khademhosseini, A.; Dehghani, F. Controlling the porosity and microarchitecture of hydrogels for tissue engineering. Tissue Eng. Part B 2010, 16, 371–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martwong, E.; Chuetor, S.; Junthip, J. Adsorption of paraquat by poly (vinyl alcohol)-cyclodextrin nanosponges. Polymers 2021, 13, 4110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Zhang, P.; Zhao, B.; Wang, S.; Zhong, J.; Cao, Z.; Liu, C.; Gong, F.; Matsuyama, H. Swelling resistance and mechanical performance of physical crosslink-based poly (vinyl alcohol) hydrogel film with various molecular weight. J. Polym. Sci. Part B Polym. Phys. 2019, 57, 1673–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, C.M.; Peppas, N.A. Structure and morphology of freeze/thawed PVA hydrogels. Macromolecules 2000, 33, 2472–2479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathan, S.G.; Fitzgerald, L.M.; Ali, S.M.; Damrauer, S.M.; Bide, M.J.; Nelson, D.W.; Ferran, C.; Phaneuf, T.M.; Phaneuf, M.D. Cytotoxicity associated with electrospun polyvinyl alcohol. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part B Appl. Biomater. 2015, 103, 1652–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, G.W.; Choi, I.W.; Park, W.S.; Oh, C.H.; Heo, S.J.; Kang, D.H.; Jung, W.K. Preparation and properties of physically cross-linked PVA/pectin hydrogels blended at different ratios for wound dressings. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2022, 139, 51696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansur, H.S.; Costa, E.D.S., Jr.; Mansur, A.A.; Barbosa-Stancioli, E.F. Cytocompatibility evaluation in cell-culture systems of chemically crosslinked chitosan/PVA hydrogels. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2009, 29, 1574–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wang, L.; Wang, T.; Li, C.; Han, W.; Chai, Y.; Liu, Z.; Ou, L.; Li, W. Functionalized carbon nanotube-embedded poly (vinyl alcohol) microspheres for efficient removal of tumor necrosis factor-α. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 6, 4722–4730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernatchez, S.F. Care of peripheral venous catheter sites: Advantages of transparent film dressings over tape and gauze. J. Assoc. Vasc. Access 2014, 19, 256–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Yan, L.; Wang, M.; Wang, K.; Fang, L.; Zhou, J.; Fang, J.; Ren, F.; Lu, X. Transparent, Adhesive, and Conductive Hydrogel for Soft Bioelectronics Based on Light-Transmitting Polydopamine Doped Polypyrrole Nanofibrils. Chem. Mater. 2018, 30, 5561−5572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Sun, M.; Zang, J.; Zhang, T.; Lv, C.; Zhao, G. Highly stretchable, transparent, and adhesive double-network hydrogel dressings tailored with fish gelatin and glycyrrhizic acid for wound healing. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 42304–42316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, C.; Ma, W.; Zhong, J. The influence of microcrystalline structure and crystalline size on visible light transmission of polyvinyl alcohol optical films. Opt. Mater. 2024, 147, 114627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suneetha, M.; Hemalatha, D.; Kim, H.; Rao, K.K.; Han, S.S. Vanillin/fungal-derived carboxy methyl chitosan/polyvinyl alcohol hydrogels prepared by freeze-thawing for wound dressing applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 266, 130910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Yan, B.; Li, T.; Long, Y.; Li, N.; Ye, M. Mechanical, thermal and swelling properties of poly (acrylic acid)–graphene oxide composite hydrogels. Soft Matter 2012, 8, 1831–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, G.; Zhou, N.; Du, S.; Gao, Y.; Suo, H.; Yang, J.; Tao, J.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, L. Transparent photothermal hydrogels for wound visualization and accelerated healing. Fundam. Res. 2022, 2, 268–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, M.; Zhao, Y.; Pan, Y.; Pan, J.; Yao, Q.; Zhang, S.; Zhao, H.; Hu, Y.; Zheng, W.; Zhou, W.; et al. A good adhesion and antibacterial double-network composite hydrogel from PVA, sodium alginate and tannic acid by chemical and physical cross-linking for wound dressings. J. Mater. Sci. 2023, 58, 5756–5772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Yu, C.; Kumar, H.; He, X.; Lu, Q.; Bai, H.; Kim, K.; Hu, J. The effect of crosslinking degree of hydrogels on hydrogel adhesion. Gels 2022, 8, 682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debele, T.A.; Su, W.P. Polysaccharide and protein-based functional wound dressing materials and applications. Int. J. Polym. Mater. Polym. Biomater. 2022, 71, 87–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bano, I.; Arshad, M.; Yasin, T.; Ghauri, M.A.; Younus, M. Chitosan: A potential biopolymer for wound management. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 102, 380–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, D.; Cao, Y.; Jiang, P.; Wang, Y.; Lu, Y.; Ji, Z.; Wang, X.; Liu, W. Tough, transparent, and slippery PVA hydrogel led by syneresis. Small 2023, 19, 2206819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ISO 10993-12:2012; Biological evaluation of medical devices—Part 12: Sample preparation and reference materials. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, S.; Liu, Y.; Li, H.; Xu, A.; Liu, W. Comparative Analysis of Physicochemical Properties and Biocompatibility of Biomass-Derived and Fossil-Derived Polyvinyl Alcohol Hydrogels: Material Screening for Wound Dressing Applications. Gels 2026, 12, 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12010006

Wang S, Liu Y, Li H, Xu A, Liu W. Comparative Analysis of Physicochemical Properties and Biocompatibility of Biomass-Derived and Fossil-Derived Polyvinyl Alcohol Hydrogels: Material Screening for Wound Dressing Applications. Gels. 2026; 12(1):6. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12010006

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Shanshan, Yun Liu, Han Li, An Xu, and Wenqing Liu. 2026. "Comparative Analysis of Physicochemical Properties and Biocompatibility of Biomass-Derived and Fossil-Derived Polyvinyl Alcohol Hydrogels: Material Screening for Wound Dressing Applications" Gels 12, no. 1: 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12010006

APA StyleWang, S., Liu, Y., Li, H., Xu, A., & Liu, W. (2026). Comparative Analysis of Physicochemical Properties and Biocompatibility of Biomass-Derived and Fossil-Derived Polyvinyl Alcohol Hydrogels: Material Screening for Wound Dressing Applications. Gels, 12(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12010006