Hydrophobic Phenolic/Silica Hybrid Aerogels for Thermal Insulation: Effect of Methyl Modification Method

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Hydrophobic Conditions and Mechanisms

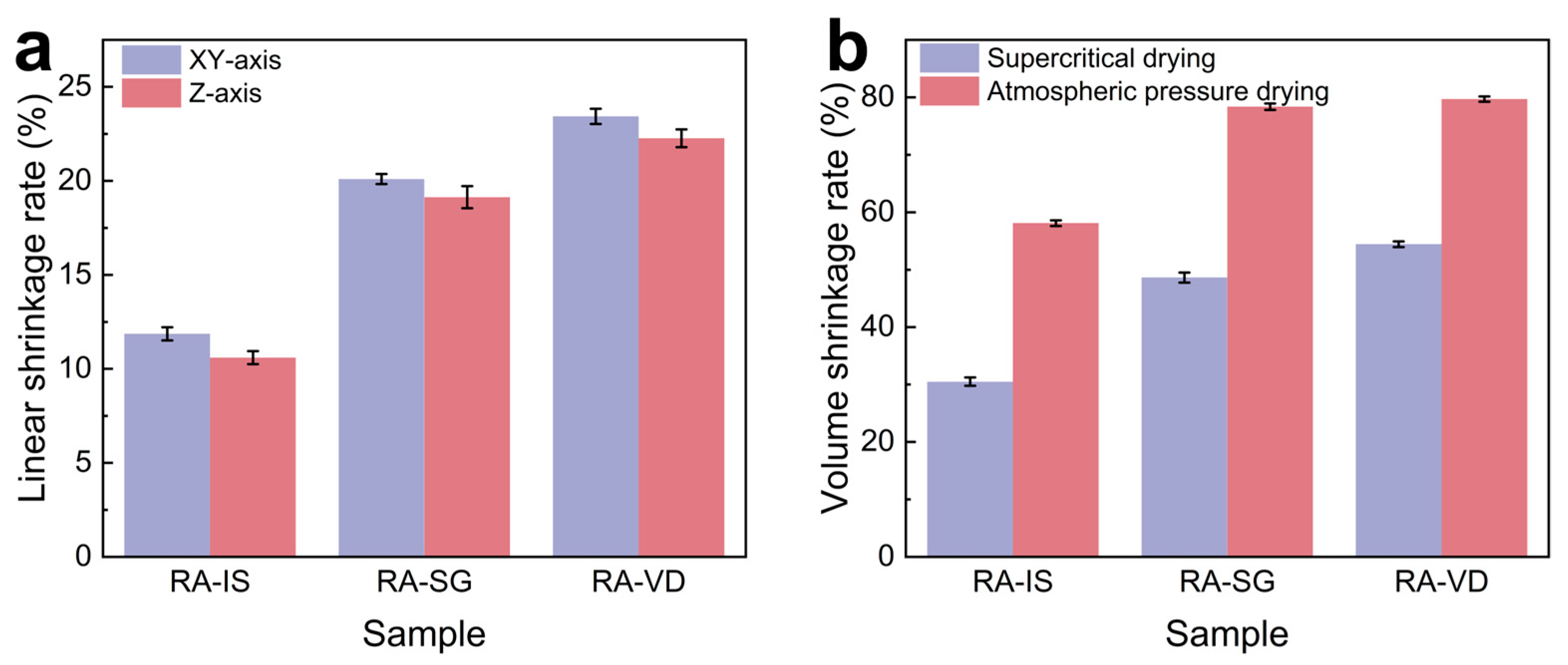

2.2. Microstructure

2.3. Hydrophobicity

2.4. Weather Resistance

2.5. Mechanical Properties

2.6. Thermal Performace

2.7. Flame Resistance

3. Conclusions

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

4.2. Synthesis

4.2.1. Synthesis of RA

4.2.2. Synthesis of RA-IS

4.2.3. Synthesis of RA-SG

4.2.4. Synthesis of RA-VD

4.3. Characterization Methods

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Soeder, D.J. Greenhouse gas sources and mitigation strategies from a geosciences perspective. Adv. Geo-Energy Res. 2021, 5, 274–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houghton, J. Global warming. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2005, 68, 1343–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandekar, M.L.; Murty, T.S.; Chittibabu, P. The Global Warming Debate: A Review of the State of Science. Pure Appl. Geophys. 2005, 162, 1557–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.L.; Han, M.Y.; Liu, S.Y.; Chen, G.Q. Energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions by buildings: A multi-scale perspective. Build. Environ. 2019, 151, 240–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ürge-Vorsatz, D.; Danny Harvey, L.D.; Mirasgedis, S.; Levine, M.D. Mitigating CO2 emissions from energy use in the world’s buildings. Build. Res. Inf. 2007, 35, 379–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenner, A.E.; Kibert, C.J.; Woo, J.; Morque, S.; Razkenari, M.; Hakim, H.; Lu, X. The carbon footprint of buildings: A review of methodologies and applications. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 94, 1142–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, G.; Ding, C.; Yu, G.; Xu, R.; Huang, X. Bridged polysilsesquioxane-derived SiOCN ceramic aerogels for microwave absorption. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2022, 106, 2407–2419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, G.; Xu, R.; Chen, Y.; Yu, G.; Wu, X.; Quan, B.; Shen, X.; Huang, X. Miniaturized Hard Carbon Nanofiber Aerogels: From Multiscale Electromagnetic Response Manipulation to Integrated Multifunctional Absorbers. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2408252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Wang, Y.; Tang, F.; Dai, X.; Zhao, Z.; Kong, Y.; Shen, X.; Shao, G. Synergistic enhancement of structure and function in carbonaceous SiC aerogels for improved microwave absorption. Carbon 2025, 233, 119854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Kong, Y.; Nie, M.; Liu, K.; Liu, Q.; Shen, X. Hydrophobic phenolic/silica aerogel composites with high fire safety and strength for efficient thermal insulation. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 43095–43105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Zhang, T.; Kong, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Zhu, K.; Zhang, X.; Shen, X. Facile synthesis of phenolic-reinforced silica aerogel composites for thermal insulation under thermal-force coupling conditions. Ceram. Int. 2023, 49, 29820–29828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Cui, Y.; Kong, Y.; Ren, J.; Jiang, X.; Yan, W.; Li, M.; Tang, J.; Liu, X.; Shen, X. Thermal and Mechanical Performances of the Superflexible, Hydrophobic, Silica-Based Aerogel for Thermal Insulation at Ultralow Temperature. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 21286–21298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Yang, Y.; Kong, Y.; Shen, X.; Shao, G. Fe3Si-Encapsulated SiC Aerogels Enable Low-Frequency Electromagnetic Wave Absorption with Extreme-Temperature Resistance and Thermal Insulation. Compos. Part B Eng. 2025, 311, 113204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Wang, Z.; Ji, H.; Wang, J.; Lu, K.; Xu, G.; Xiao, Y.; Ding, F. Mechanically Robust Nanoporous Polyimide/Silica Aerogels for Thermal Superinsulation of Aircraft. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2023, 6, 7269–7279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Kong, Y.; Shen, X. Regulating the hydrophobicity and pore structure of silica aerogel for thermal insulation under humid and high temperature conditions. J. Porous Mater. 2024, 32, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, W.; Zuo, L.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Liu, T. Mechanically strong polyimide / carbon nanotube composite aerogels with controllable porous structure. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2018, 156, 186–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Hübner, R.; Georgi, M.; Wang, C.; Wu, X.; Eychmüller, A. Controllable electrostatic manipulation of structure building blocks in noble metal aerogels. Mater. Adv. 2022, 3, 5760–5771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, C.; Wang, D.; Zhang, Y.; Li, K.; Ding, J. Research progress on preparation, modification, and application of phenolic aerogel. Nanotechnol. Rev. 2023, 12, 20230109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Hou, F.; Kong, Y.; Zhang, C. Development of flexible and anisotropic long glass fiber paper by foam forming for high performance silica aerogel composites. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 525, 170140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Y.; Tan, Z.; Tang, F.; Shen, X. Facile synthesis of hydrophobic amine-functionalized silica aerogel with low regeneration temperature and long-term stability for efficient direct air capture. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 520, 166295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Lv, Y.; Jin, X.; Wang, H.; Wu, C.; Pan, Y.; Yan, X.; Hong, C.; Han, W.; Zhang, X. Bifunctional silicone triggered long-range crosslinking phenolic aerogels with flexibility and thermal insulation for thermal regulation. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 470, 144413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bari, G.; Jeong, J.H. Potential of Carbon Aerogels in Energy: Design, Characteristics, and Applications. Gels 2024, 10, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Cheng, H.; Hong, C.; Zhang, X.; Zeng, T. Lightweight chopped carbon fibre reinforced silica-phenolic resin aerogel nanocomposite: Facile preparation, properties and application to thermal protection. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2018, 112, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Chen, Z.; Wang, F.; Hu, Y.; Rao, Z.; Wang, E.; Zhang, X. Preparation and characterization of ultralight glass fiber wool/phenolic resin aerogels with a spring-like structure. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2019, 179, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Y.; Zhong, Y.; Shen, X.; Cui, S.; Fan, M. Effect of silica sources on nanostructures of resorcinol–formaldehyde/silica and carbon/silicon carbide composite aerogels. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2014, 197, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshavarz, L.; Ghaani, M.R.; English, N.J. The Importance of Precursors and Modification Groups of Aerogels in CO2 Capture. Molecules 2021, 26, 5023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, W.; Chen, L.; Kong, Q.; Li, L.; Chen, M.; Jiang, J.; Li, W.; Shi, F.; Xu, Z. The Synthesis and Polymer-Reinforced Mechanical Properties of SiO2 Aerogels: A Review. Molecules 2023, 28, 5534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekala, R.W. Organic aerogels from the polycondensation of resorcinol with formaldehyde. J. Mater. Sci. 1989, 24, 3221–3227.123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Arduini-Schuster, M.C.; Kuhn, J.; Nilsson, O.; Fricke, J.; Pekala, R.W. Thermal Conductivity of Monolithic Organic Aerogels. Science 1992, 255, 971–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwan, M.; Naikade, M.; Raabe, D.; Ratke, L. From hard to rubber-like: Mechanical properties of resorcinol–formaldehyde aerogels. J. Mater. Sci. 2015, 50, 5482–5493.123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamal Mohamed, S.M.; Heinrich, C.; Milow, B. Effect of Process Conditions on the Properties of Resorcinol-Formaldehyde Aerogel Microparticles Produced via Emulsion-Gelation Method. Polymers 2021, 13, 2409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, D.; Lv, H.; Zheng, Z.; Luo, L. Preparation and Properties of Flexible Phenolic Silicone Hybrid Aerogels for Thermal Insulation. Molecules 2024, 29, 4942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Wang, Z.; Wang, J.; Xiao, Y.; Yang, Z.; Ji, H.; Xu, G.; Xiong, S.; Li, Z.; Ding, F. Polyimide Aerogels with Excellent Thermal Insulation, Hydrophobicity, Machinability, and Strength Evolution at Extreme Conditions. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2022, 4, 8227–8237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganonyan, N.; Bar, G.; Gvishi, R.; Avnir, D. Gradual hydrophobization of silica aerogel for controlled drug release. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 7824–7838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niculescu, A.G.; Tudorache, D.I.; Bocioaga, M.; Mihaiescu, D.E.; Hadibarata, T.; Grumezescu, A.M. An Updated Overview of Silica Aerogel-Based Nanomaterials. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Yu, Y.; Cheng, X.; Zhang, Y. Preparation and surface modification mechanism of silica aerogels via ambient pressure drying. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2011, 129, 308–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Xia, M.; Luo, F.; Li, N.; Guo, C.; Wei, C. Effect of surface modification on physical properties of silica aerogels derived from fly ash acid sludge. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2016, 490, 200–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, J.; Shan, Y.; Zou, C.; Hong, Y.; Liu, J.; Guo, X. Cost-Effective Preparation of Hydrophobic and Thermal-Insulating Silica Aerogels. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.L.; Wang, Y.T.; Zhang, S.J.; Sun, M.Z.; Li, J.; Chu, L.Q.; Hu, C.X.; Huang, Y.L.; Gao, D.L.; Schiraldi, D.A. A Novel, Controllable, and Efficient Method for Building Highly Hydrophobic Aerogels. Gels 2024, 10, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Jiang, S.; Li, M.; Wang, N.; Liu, L.; Liu, L.; Ge, A. Superior stable, hydrophobic and multifunctional nanocellulose hybrid aerogel via rapid UV induced in-situ polymerization. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 288, 119370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rafieian, F.; Hosseini, M.; Jonoobi, M.; Yu, Q. Development of hydrophobic nanocellulose-based aerogel via chemical vapor deposition for oil separation for water treatment. Cellulose 2018, 25, 4695–4710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Effraimopoulou, E.; Jaxel, J.; Budtova, T.; Rigacci, A. Hydrophobic Modification of Pectin Aerogels via Chemical Vapor Deposition. Polymers 2024, 16, 1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Yu, D.; Xu, F.; Kong, Y.; Shen, X. Flexible Silica Aerogel Composites for Thermal Insulation under High-Temperature and Thermal–Force Coupling Conditions. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2024, 7, 6326–6338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Y.; Zhong, Y.; Shen, X.; Cui, S.; Yang, M.; Teng, K.; Zhang, J. Facile synthesis of resorcinol–formaldehyde/silica composite aerogels and their transformation to monolithic carbon/silica and carbon/silicon carbide composite aerogels. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2012, 358, 3150–3155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Y.; Zhong, Y.; Shen, X.; Gu, L.; Cui, S.; Yang, M. Synthesis of monolithic mesoporous silicon carbide from resorcinol–formaldehyde/silica composites. Mater. Lett. 2013, 99, 108–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Civioc, R.; Malfait, W.J.; Lattuada, M.; Koebel, M.M.; Galmarini, S. Silica-Resorcinol-Melamine-Formaldehyde Composite Aerogels as High-Performance Thermal Insulators. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 14478–14489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthon-Fabry, S.; Hildenbrand, C.; Ilbizian, P. Lightweight superinsulating Resorcinol-Formaldehyde-APTES benzoxazine. Eur. Polym. J. 2016, 78, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cychosz, K.A.; Thommes, M. Progress in the Physisorption Characterization of Nanoporous Gas Storage Materials. Engineering 2018, 4, 559–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Feng, J.; Feng, J. Synthesis and characterization of ambient-dried microglass fibers/silica aerogel nanocomposites with low thermal conductivity. J. Sol-Gel Sci. Technol. 2017, 83, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Zhu, W.; Kong, Y.; Chu, C.; Shen, X. New insights into the resistance of hydrophobic silica aerogel composite to water, moisture, temperature and heat-stress coupling. Ceram. Int. 2024, 50, 38189–38199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durães, L.; Maia, A.; Portugal, A. Effect of additives on the properties of silica based aerogels synthesized from methyltrimethoxysilane (MTMS). J. Supercrit. Fluids 2015, 106, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Oweini, R.; Rassy, H. Synthesis and Characterization by FTIR Spectroscopy of Silica Aerogels Prepared Using Several Si(OR)4 and R″Si(OR′)3 Precursors. J. Mol. Struct. 2009, 919, 140–145.123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarawade, P.; Kim, J.; Kim, H.-K.; Kim, H.T. High specific surface area TEOS-based aerogels with large pore volume prepared at an ambient pressure. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2007, 254, 574–579.7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sodeifian, G.; Nikooamal, H.R.; Yousefi, A.A. Molecular dynamics study of epoxy/clay nanocomposites: Rheology and molecular confinement. J. Polym. Res. 2012, 19, 9897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, R.; Dai, J.; Wang, B.; Sha, J. Improving Pore Characteristics, Mechanical Properties and Thermal Performances of Near-Net Shape Manufacturing Phenolic Resin Aerogels. Polymers 2024, 16, 1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z.; Zheng, Z.; Zuo, X.; Luo, L.; Guo, Y. Facile Preparation of Flexible Phenolic-Silicone Aerogels with Good Thermal Stability and Fire Resistance. Molecules 2025, 30, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwan, M.; Tannert, R.; Ratke, L. New soft and spongy resorcinol–formaldehyde aerogels. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2016, 107, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwan, M.; Ratke, L. Flexibilisation of resorcinol–formaldehyde aerogels. J. Mater. Chem. A 2013, 1, 13462–13468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, K.; Yang, J.C.; Cao, Z.J.; Liao, W.; Wang, Y.Z.; Schiraldi, D.A. Novel Polymer Aerogel toward High Dimensional Stability, Mechanical Property, and Fire Safety. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 22985–22993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simón-Herrero, C.; Gómez, L.; Romero, A.; Valverde, J.L.; Sánchez-Silva, L. Nanoclay-Based PVA Aerogels: Synthesis and Characterization. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2018, 57, 6218–6225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Pan, Y.; Gong, L.; Yao, X.; Cheng, X.; Deng, Y. Mechanically strong polyimide aerogels cross-linked with low-cost polymers. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 10827–10835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filimonova, E.; Bergmann, T.; Zhao, S.; Dyatlov, V.A.; Malfait, W.J.; Wu, T. Effect of polymer concentration and cross-linking density on the microstructure and properties of polyimide aerogels. J. Sol-Gel Sci. Technol. 2024, 110, 747–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, M.; Liu, B.-W.; Zhang, L.; Peng, Z.-C.; Zhang, Y.-Y.; Wang, H.; Zhao, H.-B.; Wang, Y.-Z. Fully biomass-based aerogels with ultrahigh mechanical modulus, enhanced flame retardancy, and great thermal insulation applications. Compos. Part B Eng. 2021, 225, 109309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghimire, S.; Sala, M.R.; Chandrasekaran, S.; Raptopoulos, G.; Worsley, M.; Paraskevopoulou, P.; Leventis, N.; Sabri, F. Noninvasive Detection, Tracking, and Characterization of Aerogel Implants Using Diagnostic Ultrasound. Polymers 2022, 14, 722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldino, L.; Concilio, S.; Cardea, S.; Reverchon, E. Interpenetration of Natural Polymer Aerogels by Supercritical Drying. Polymers 2016, 8, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchtova, N.; Pradille, C.; Bouvard, J.L.; Budtova, T. Mechanical properties of cellulose aerogels and cryogels. Soft Matter 2019, 15, 7901–7908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi Heidari, N.; Fathi, M.; Hamdami, N.; Taheri, H.; Siqueira, G.; Nyström, G. Thermally Insulating Cellulose Nanofiber Aerogels from Brewery Residues. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 10698–10708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulauskiene, T.; Sirtaute, E.; Tadzijevas, A.; Uebe, J. Mechanical Properties of Cellulose Aerogel Composites with and without Crude Oil Filling. Gels 2024, 10, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, S.; Luo, H.; Gao, Y. Ambient-pressure drying synthesis of large resorcinol–formaldehyde-reinforced silica aerogels with enhanced mechanical strength and superhydrophobicity. J. Mater. Chem. A 2014, 2, 14542–14549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleki, H.; Durães, L.; Portugal, A. Synthesis of lightweight polymer-reinforced silica aerogels with improved mechanical and thermal insulation properties for space applications. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2014, 197, 116–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.; Cheng, H.; Hong, C.; Zhang, X. Synthesis and characterization of novel phenolic resin/silicone hybrid aerogel composites with enhanced thermal, mechanical and ablative properties. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2017, 101, 500–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Fan, Z.; Hong, C.; Zhang, X. Lightweight multiscale hybrid carbon-quartz fiber fabric reinforced phenolic-silica aerogel nanocomposite for high temperature thermal protection. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2021, 143, 106313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, R.; Cheng, X.; Dai, J.; Zu, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Sha, J. Lightweight phenolic resin aerogel with excellent thermal insulation and mechanical properties via an ultralow shrinkage process. Mater. Lett. 2022, 324, 132626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Jin, X.; Huang, H.; Hu, S.; Wu, C.; Wang, H.; Pan, Y.; Hong, C.; Zhang, X. Thermal-insulation and ablation-resistance of Ti-Si binary modified carbon/phenolic nanocomposites for high-temperature thermal protection. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2023, 169, 107528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, W.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, T. Lightweight, strong, and super-thermal insulating polyimide composite aerogels under high temperature. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2019, 173, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.-Y.; Zhu, C.-Y.; Zhao, X.-P. A theoretical and numerical study on the gas-contributed thermal conductivity in aerogel. Int. J. Heat. Mass. Transf. 2017, 108, 1982–1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goryunova, K.I.; Gahramanli, Y.N. Insulating materials based on silica aerogel composites: Synthesis, properties and application. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 34690–34707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sample | Theoretical Density (g·cm−3) | Bulk Density (g·cm−3) | Specific Surface Area (m2·g−1) | Pore Volume (cm3·g−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RA-IS | 0.12 | 0.25 ± 0.01 | 401 | 1.875 |

| RA-SG | 0.12 * | 0.35 ± 0.02 | 377 | 1.869 |

| RA-VD | 0.12 * | 0.40 ± 0.02 | 310 | 1.450 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Nie, M.; Kong, Y.; Wang, Z.; Xu, F.; Zhou, J.; Shen, X. Hydrophobic Phenolic/Silica Hybrid Aerogels for Thermal Insulation: Effect of Methyl Modification Method. Gels 2026, 12, 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12010004

Nie M, Kong Y, Wang Z, Xu F, Zhou J, Shen X. Hydrophobic Phenolic/Silica Hybrid Aerogels for Thermal Insulation: Effect of Methyl Modification Method. Gels. 2026; 12(1):4. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12010004

Chicago/Turabian StyleNie, Mengcheng, Yong Kong, Zhixin Wang, Fuhao Xu, Jiantao Zhou, and Xiaodong Shen. 2026. "Hydrophobic Phenolic/Silica Hybrid Aerogels for Thermal Insulation: Effect of Methyl Modification Method" Gels 12, no. 1: 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12010004

APA StyleNie, M., Kong, Y., Wang, Z., Xu, F., Zhou, J., & Shen, X. (2026). Hydrophobic Phenolic/Silica Hybrid Aerogels for Thermal Insulation: Effect of Methyl Modification Method. Gels, 12(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12010004