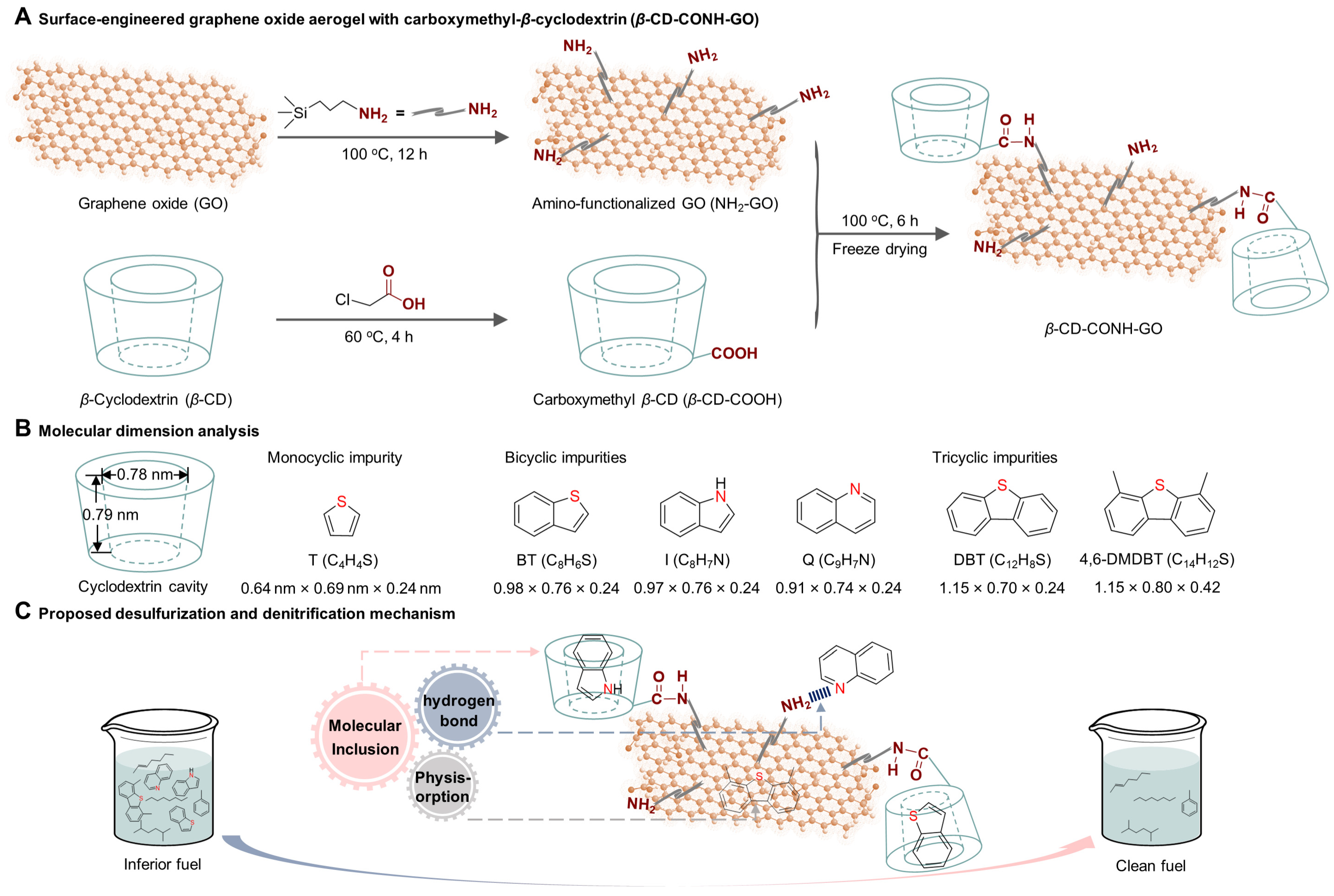

Surface-Engineered Amino-Graphene Oxide Aerogel Functionalized with Cyclodextrin for Desulfurization and Denitrogenation in Oil Refining

Abstract

1. Introduction

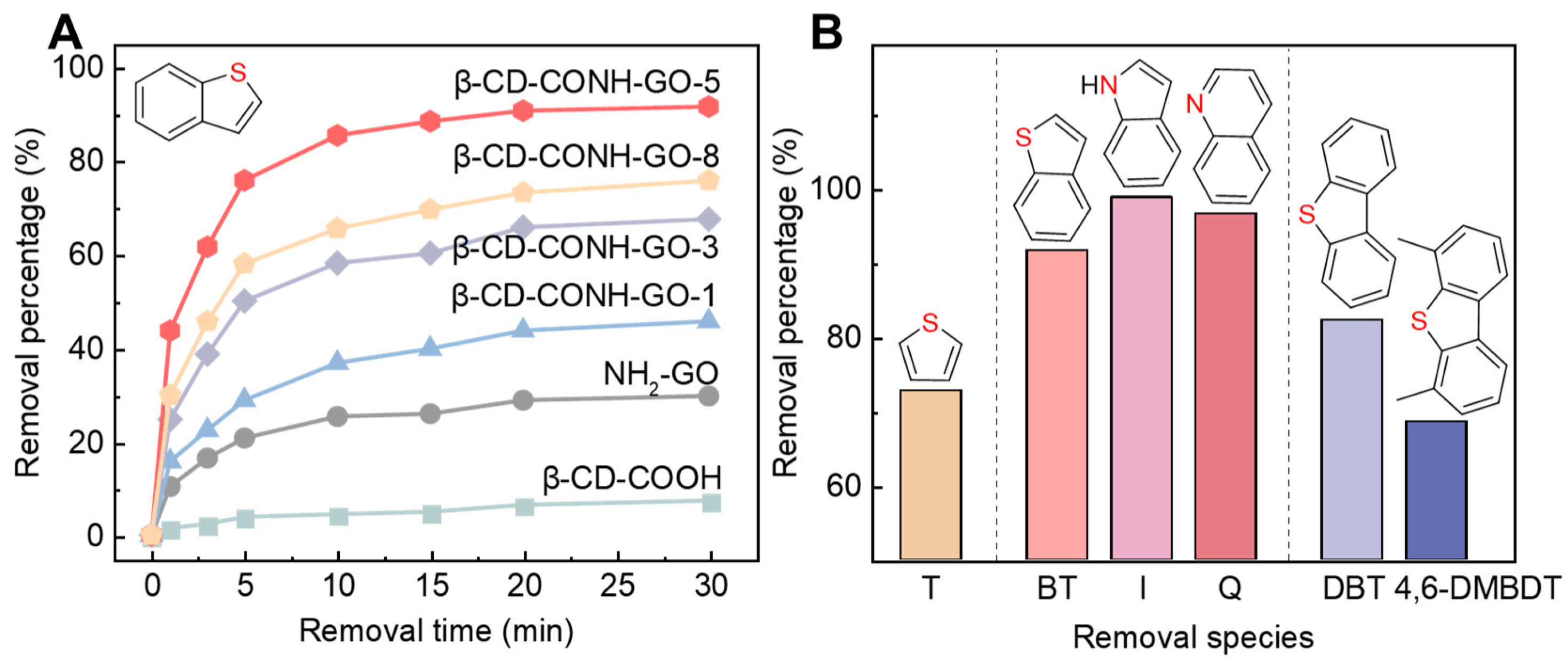

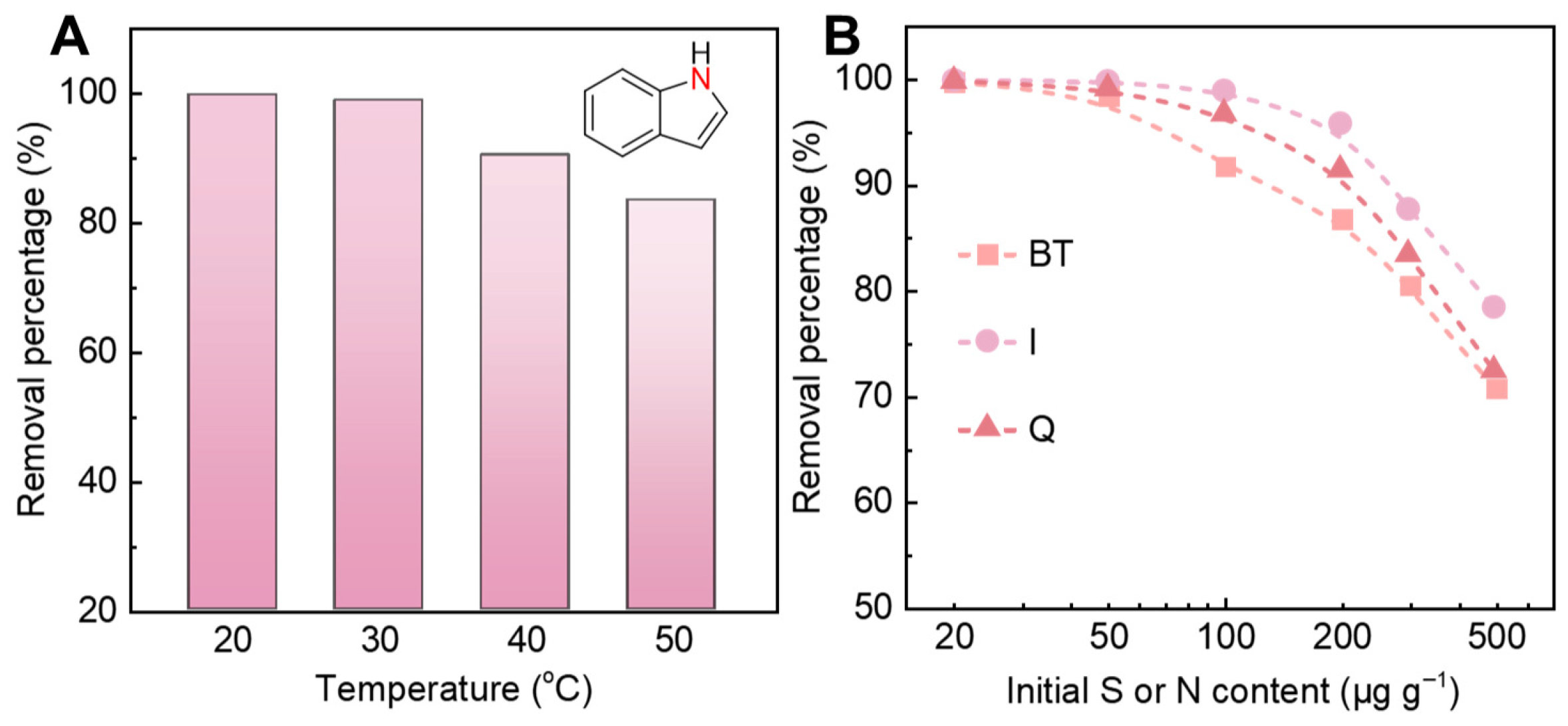

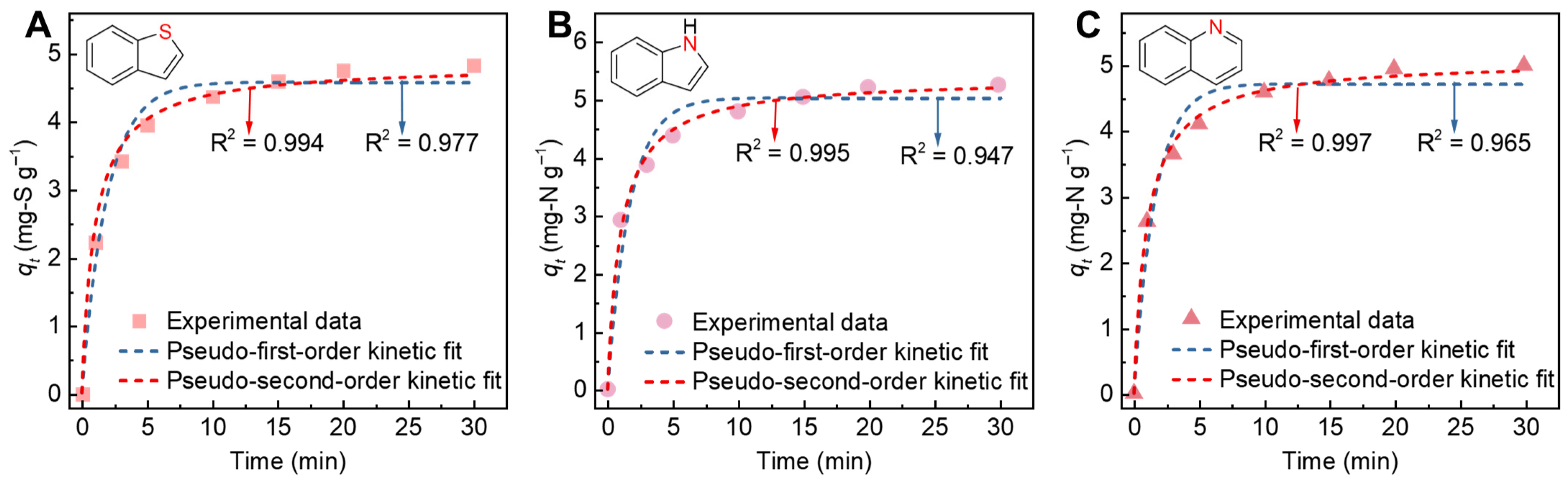

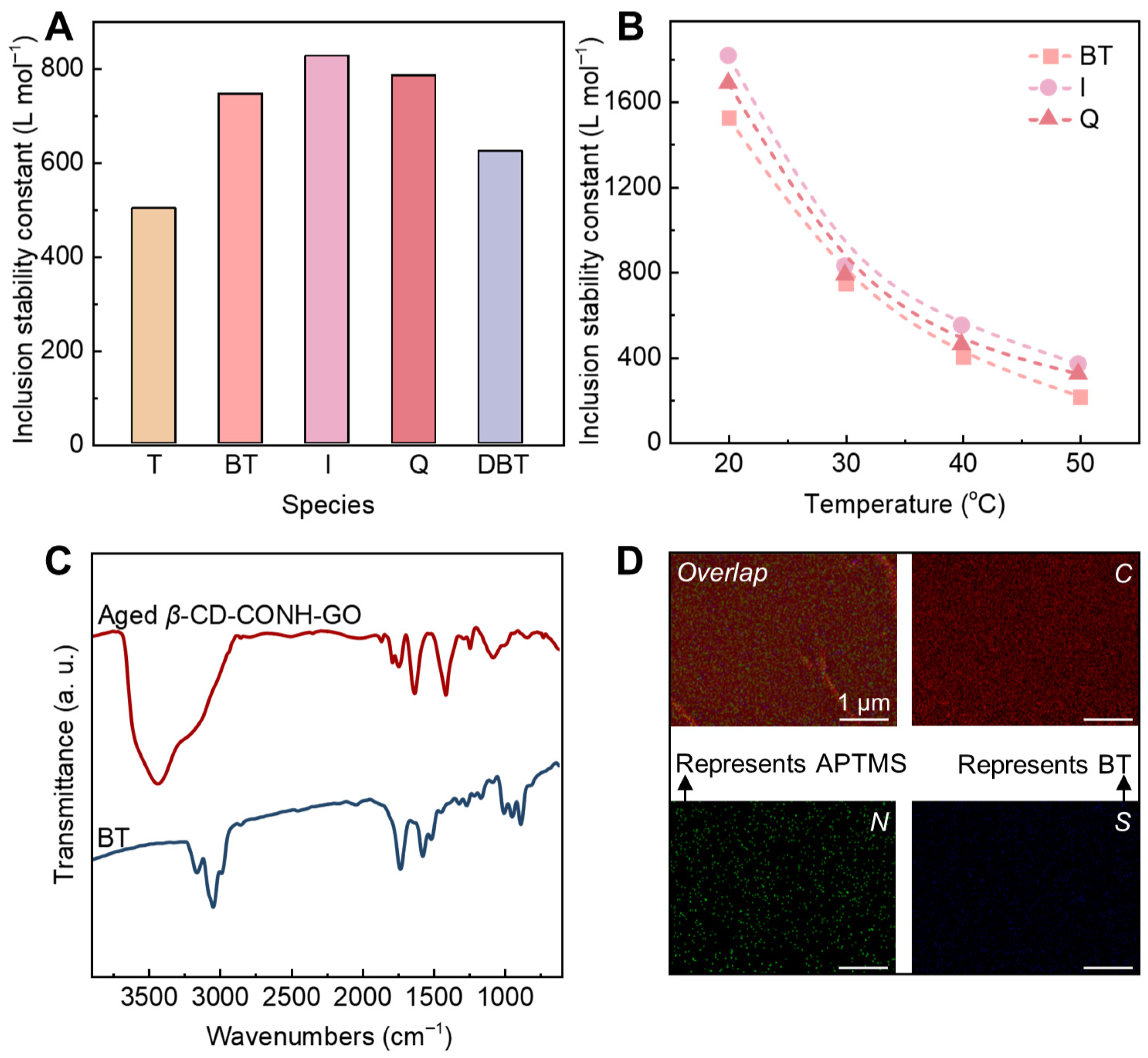

2. Results and Discussion

3. Conclusions

4. Materials and Methods

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hansmeier, A.R.; Meindersma, G.W.; de Haan, A.B. Desulfurization and denitrogenation of gasoline and diesel fuels by means of ionic liquids. Green Chem. 2011, 13, 1907–1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Q.; Wu, J. Review on sulfur compounds in petroleum and its products: State-of-the-art and perspectives. Energy Fuels 2021, 35, 14445–14461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanimu, A.; Alhooshani, K. Advanced hydrodesulfurization catalysts: A review of design and synthesis. Energy Fuels 2019, 33, 2810–2838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babich, I.V.; Moulijn, J.A. Science and technology of novel processes for deep desulfurization of oil refinery streams: A review. Fuel 2003, 82, 607–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furimsky, E.; Massoth, F.E. Hydrodenitrogenation of petroleum. Catal. Rev. 2005, 47, 297–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuman, S.C.; Shalit, H. Hydrodesulfurization. Catal. Rev. 1971, 4, 245–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niquille-Röthlisberger, A.; Prins, R. Hydrodesulfurization of 4, 6-dimethyldibenzothiophene and dibenzothiophene over alumina-supported pt, pd, and pt-pd catalysts. J. Catal. 2006, 242, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, M.; Song, J.Y.; Jeong, A.R.; Min, K.S.; Jhung, S.H. Adsorptive removal of indole and quinoline from model fuel using adenine-grafted metal-organic frameworks. J. Hazard. Mater. 2018, 344, 593–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MK, S.B.; Mehra, S.; Kumar, A.; Kancharla, S. Diesel purification through imidazole-based deep eutectic solvents: Desulfurization, dearomatization, and denitrogenation. Fuel 2025, 387, 134317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Huang, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, D.; Zhang, H. Facile and controllable preparation of nanosheet hierarchical y for enhanced adsorptive denitrogenation from fuels. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 328, 125100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishihara, A.; Wang, D.; Dumeignil, F.; Amano, H.; Qian, E.W.; Kabe, T. Oxidative desulfurization and denitrogenation of a light gas oil using an oxidation/adsorption continuous flow process. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2005, 279, 279–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Ma, X.; Zhou, A.; Song, C. Ultra-deep desulfurization and denitrogenation of diesel fuel by selective adsorption over three different adsorbents: A study on adsorptive selectivity and mechanism. Catal. Today 2006, 111, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Z.; Bian, H.; Zhu, L.; Xia, D. Efficient removal of thiophenic sulfides from fuel by micro-mesoporous 2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin polymers through synergistic effect. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2022, 300, 121884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Z.; Bu, T.; Bian, H.; Zhu, L.; Xiang, Y.; Xia, D. Effective removal of phenylamine, quinoline, and indole from light oil by β-cyclodextrin aqueous solution through molecular inclusion. Energy Fuels 2018, 32, 9280–9288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Z.; Wei, S.; Bian, H.; Guan, C.; Zhu, L.; Xia, D. Inclusion as an efficient purification method for specific removal of tricyclic organic sulfur/nitrogen pollutants in fuel and effluent with cyclodextrin polymers. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2021, 254, 117643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szejtli, J. Introduction and general overview of cyclodextrin chemistry. Chem. Rev. 1998, 98, 1743–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Shi, Y.; Li, L.; Zhang, Z.; Cao, N.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, K. Recent progress on the porous cyclodextrin polymers in water treatment. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2025, 541, 216826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezvani, M.A.; Khandan, S.; Sabahi, N.; Saeidian, H. Deep oxidative desulfurization of gas oil based on sandwich-type polysilicotungstate supported β-cyclodextrin composite as an efficient heterogeneous catalyst. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2019, 27, 2418–2426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Li, G.; Gui, C.; Song, M.; Zhao, F.; Yang, S.; Lei, Z.; Xu, P. Enhancing aromatic VOCs capture using randomly methylated β-cyclodextrin-modified deep eutectic solvents. AIChE J. 2025, 71, e18918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Z.; Bian, H.; Gao, Z.; Zhu, L.; Xia, D. Green fuel desulfurization with β-cyclodextrin aqueous solution for thiophenic sulfides by molecular inclusion. Energy Fuels 2019, 33, 9690–9701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harada, A.; Takashima, Y.; Yamaguchi, H. Cyclodextrin-based supramolecular polymers. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009, 38, 875–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Z.; Ding, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, L.; Xia, D. A new strategy for fuel desulfurization by molecular inclusion with copper(II)-β-cyclodextrin@SiO2 @Fe3O4 for removing thiophenic sulfides. Energy Fuels 2018, 32, 11421–11431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottari, G.; Herranz, M.Á.; Wibmer, L.; Volland, M.; Rodríguez-Pérez, L.; Guldi, D.M.; Hirsch, A.; Martín, N.; D’Souza, F.; Torres, T. Chemical functionalization and characterization of graphene-based materials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017, 46, 4464–4500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres, T. Graphene chemistry. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017, 46, 4385–4386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dreyer, D.R.; Park, S.; Bielawski, C.W.; Ruoff, R.S. The chemistry of graphene oxide. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010, 39, 228–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinelli, F.; Nespoli, T.; Rossi, F. Graphene oxide-chitosan aerogels: Synthesis, characterization, and use as adsorbent material for water contaminants. Gels 2021, 7, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman, F.F.; Diaz De Tuesta, J.L.; Silva, A.M.; Faria, J.L.; Gomes, H.T. Carbon-based materials for oxidative desulfurization and denitrogenation of fuels: A review. Catalysts 2021, 11, 1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Z.; Zhang, M.; Bian, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, L.; Xiang, Y.; Xia, D. Copper(II)-β-cyclodextrin and CuO functionalized graphene oxide composite for fast removal of thiophenic sulfides with high efficiency. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 228, 115385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasprzak, A.; Poplawska, M. Recent developments in the synthesis and applications of graphene-family materials functionalized with cyclodextrins. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 8547–8562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faria, R.G.; Silva, D.; Mirante, F.; Gago, S.; Cunha-Silva, L.; Balula, S.S. Advanced technologies conciliating desulfurization and denitrogenation to prepare clean fuels. Catalysts 2024, 14, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Souza, V.T.; Lipkowitz, K.B. Cyclodextrins: Introduction. Chem. Rev. 1998, 98, 1741–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crini, G. A history of cyclodextrins. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 10940–10975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, A.J.; Söderman, O. The formation of host–guest complexes between surfactants and cyclodextrins. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2014, 205, 156–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinilla-Peñalver, E.; Soriano, M.L.; Contento, A.M.; Ríos, Á. Cyclodextrin-modified graphene quantum dots as a novel additive for the selective separation of bioactive compounds by capillary electrophoresis. Mikrochim. Acta 2021, 188, 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szente, L.; Fenyvesi, É. Cyclodextrin-lipid complexes: Cavity size matters. Struct. Chem. 2017, 28, 479–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsbaiee, A.; Smith, B.J.; Xiao, L.; Ling, Y.; Helbling, D.E.; Dichtel, W.R. Rapid removal of organic micropollutants from water by a porous β-cyclodextrin polymer. Nature 2016, 529, 190–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saenger, W. Cyclodextrin inclusion compounds in research and industry. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1980, 19, 344–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eftink, M.R.; Andy, M.L.; Bystrom, K.; Perlmutter, H.D.; Kristol, D.S. Cyclodextrin inclusion complexes: Studies of the variation in the size of alicyclic guests. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1989, 111, 6765–6772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Wei, L.; Lu, L.; Shen, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Tan, X. Structural manipulation of 3D graphene-based macrostructures for water purification. Gels 2022, 8, 622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzyka, R.; Kwoka, M.; Smędowski, Ł.; Díez, N.; Gryglewicz, G. Oxidation of graphite by different modified hummers methods. New Carbon Mater. 2017, 32, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcano, D.C.; Kosynkin, D.V.; Berlin, J.M.; Sinitskii, A.; Sun, Z.; Slesarev, A.; Alemany, L.B.; Lu, W.; Tour, J.M. Improved synthesis of graphene oxide. ACS Nano 2010, 4, 4806–4814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, Z.; Feng, X.; Lai, G.; Liu, D.; Zhang, X.; Wang, H.; Chen, S.; He, X.; Liu, Z.; Tong, L.; et al. Promoting nitrogen-doped porous phosphorus spheres for high-rate lithium storage. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2024, 679, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, A.C.; Basko, D.M. Raman spectroscopy as a versatile tool for studying the properties of graphene. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2013, 8, 235–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, Z.; Li, R.; Bian, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Cheng, Z.; Liu, D.; Li, Y.; Zhang, S.; Qu, G.; et al. Large-scale synthesis of crystalline phosphorus nanosheets with superior air-water stability and flame-retardancy ability. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 505, 159566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, A.C.; Meyer, J.C.; Scardaci, V.; Casiraghi, C.; Lazzeri, M.; Mauri, F.; Piscanec, S.; Jiang, D.; Novoselov, K.S.; Roth, S. Raman spectrum of graphene and graphene layers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2006, 97, 187401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonin, J. On the comparison of pseudo-first order and pseudo-second order rate laws in the modeling of adsorption kinetics. Chem. Eng. J. 2016, 300, 254–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hădărugă, N.G.; Bandur, G.N.; David, I.; Hădărugă, D.I. A review on thermal analyses of cyclodextrins and cyclodextrin complexes. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2019, 17, 349–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannwarth, C.; Ehlert, S.; Grimme, S. GFN2-xTB—An accurate and broadly parametrized self-consistent tight-binding quantum chemical method with multipole electrostatics and density-dependent dispersion contributions. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2019, 15, 1652–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Duan, Z.; Chen, J.; Zhou, Y.; Zhu, L.; Xiang, Y.; Xia, D. Molecular recognition with cyclodextrin polymer: A novel method for removing sulfides efficiently. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 38902–38910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Jia, X.; Bian, H.; Huo, T.; Duan, Z.; Xiang, Y.; Xia, D. Structure and adsorptive desulfurization performance of the composite material MOF-5@AC. New J. Chem. 2018, 42, 384–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalse, N.M.; De, M. Adsorptive desulfurization of thiophenic sulfur compounds using nitrogen modified graphene. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 331, 125693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Zuhra, Z.; Qin, L.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, L.; Tang, F.; Mu, C. Confinement of microporous MOF-74(Ni) within mesoporous γ-Al2O3 beads for excellent ultra-deep and selective adsorptive desulfurization performance. Fuel Process. Technol. 2018, 176, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Samples | BET Surface Area (m2 g−1) | Pore Diameter (nm) | Volume Pores (cm3 g−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| NH2-GO | 1098.6 | 2.89 | 0.74 |

| β-CD-CONH-GO-1 | 954.6 | 2.68 | 0.67 |

| β-CD-CONH-GO-3 | 944.1 | 2.72 | 0.62 |

| β-CD-CONH-GO-5 | 926.7 | 2.75 | 0.59 |

| β-CD-CONH-GO-8 | 904.6 | 2.71 | 0.57 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Duan, Z.; Zhang, H.; Tong, Q.; Li, Y.; Bian, H.; Zhang, G. Surface-Engineered Amino-Graphene Oxide Aerogel Functionalized with Cyclodextrin for Desulfurization and Denitrogenation in Oil Refining. Gels 2026, 12, 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12010033

Duan Z, Zhang H, Tong Q, Li Y, Bian H, Zhang G. Surface-Engineered Amino-Graphene Oxide Aerogel Functionalized with Cyclodextrin for Desulfurization and Denitrogenation in Oil Refining. Gels. 2026; 12(1):33. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12010033

Chicago/Turabian StyleDuan, Zunbin, Huiming Zhang, Qiang Tong, Yanfang Li, He Bian, and Guanglei Zhang. 2026. "Surface-Engineered Amino-Graphene Oxide Aerogel Functionalized with Cyclodextrin for Desulfurization and Denitrogenation in Oil Refining" Gels 12, no. 1: 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12010033

APA StyleDuan, Z., Zhang, H., Tong, Q., Li, Y., Bian, H., & Zhang, G. (2026). Surface-Engineered Amino-Graphene Oxide Aerogel Functionalized with Cyclodextrin for Desulfurization and Denitrogenation in Oil Refining. Gels, 12(1), 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12010033