2.1. Synthesis and Characterization of Copolymers

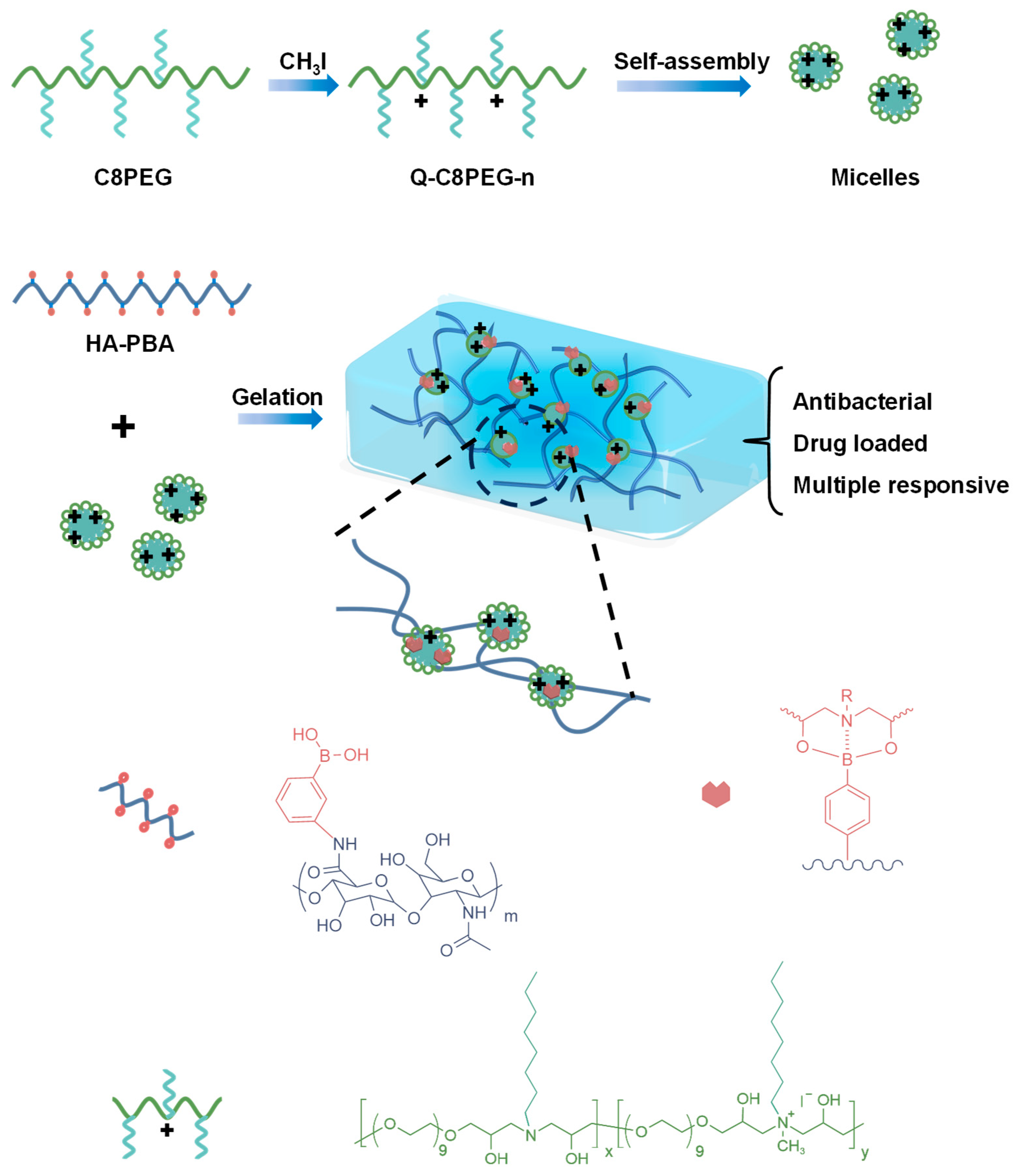

C8PEG was synthesized according to our previous work [

27], via the amine–epoxy click reaction between poly(ethylene glycol) diglycidyl ether (PEGDE) and

n-octylamine (C8-NH

2), yielding a colorless viscous liquid (86%). Subsequently, different concentrations of iodomethane (CH

3I) were added to the methanol solution of C8PEG, and the mixture was stirred at room temperature for 36 h, after which amphiphilic quaternized copolymers (Q-C8PEG-n) were obtained with yields exceeding 80% (

Figure 1). The structural formulas are presented in

Figure S1. To confirm the molecular structures,

1H NMR characterization was performed on C8PEG, partially quaternized polymers Q-C8PEG-1, Q-C8PEG-2, Q-C8PEG-3, as well as the fully quaternized polymer Q-C8PEG-4 (

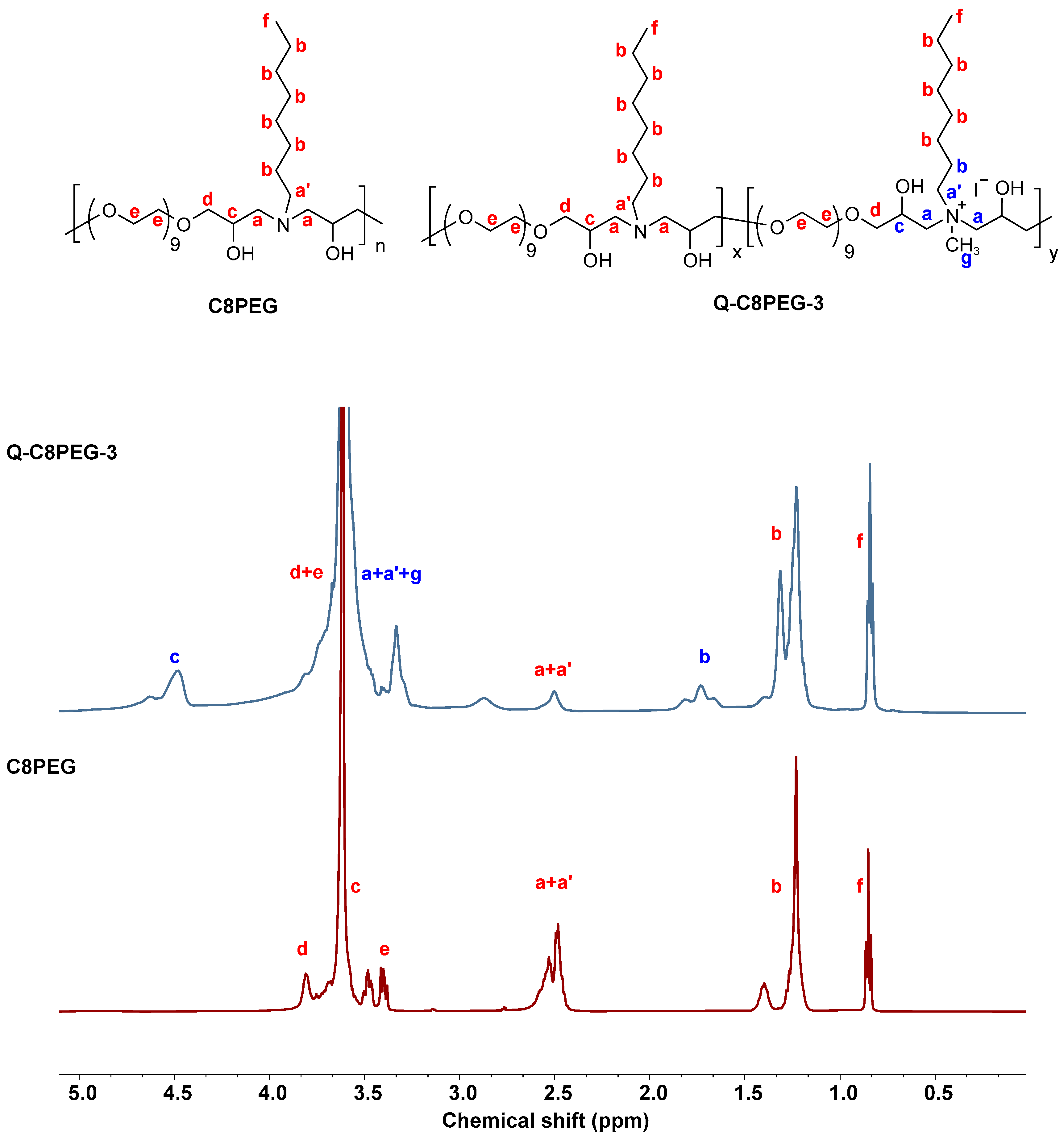

Figures S2–S6). Comparison of the spectra revealed distinct changes indicative of successful quaternization. To further verify successful quaternization and assign proton couplings,

1H-

1H COSY was employed for C8PEG, Q-C8PEG-2, Q-C8PEG-3, and Q-C8PEG-4. As shown in

Figure 2, the chemical shifts of the methylene protons adjacent to the tertiary amine sites (labeled a and a’) shifted downfield to 3.3 ppm after quaternization, reflecting the increased electron withdrawal due to the positively charged quaternary ammonium group. Similarly, the methylene protons on the alkyl chain (b) shifted from 1.4 ppm to 1.7 ppm, consistent with deshielding effects from quaternization. The COSY spectra of Q-C8PEG-2 and Q-C8PEG-3 (

Figures S8 and S9) displayed two distinct

1H-

1H coupling signals between a’ and b, confirming the structural integrity of the modified chains. Additionally, the methine proton (c) adjacent to the hydroxyl group in the PEGDE segment shifted from 3.4 ppm to 4.5 ppm post-quaternization, with coupling signals between c and a observed in the COSY spectra of Q-C8PEG-2, Q-C8PEG-3, and Q-C8PEG-4 (

Figures S8–S10). Notably, as the degree of quaternization increased, the integral area of the signal for proton c also grew, providing quantitative evidence of progressive modification. These NMR and COSY results collectively demonstrate the successful and tunable quaternization of C8PEG, enabling control over the amphiphilic balance in the copolymers.

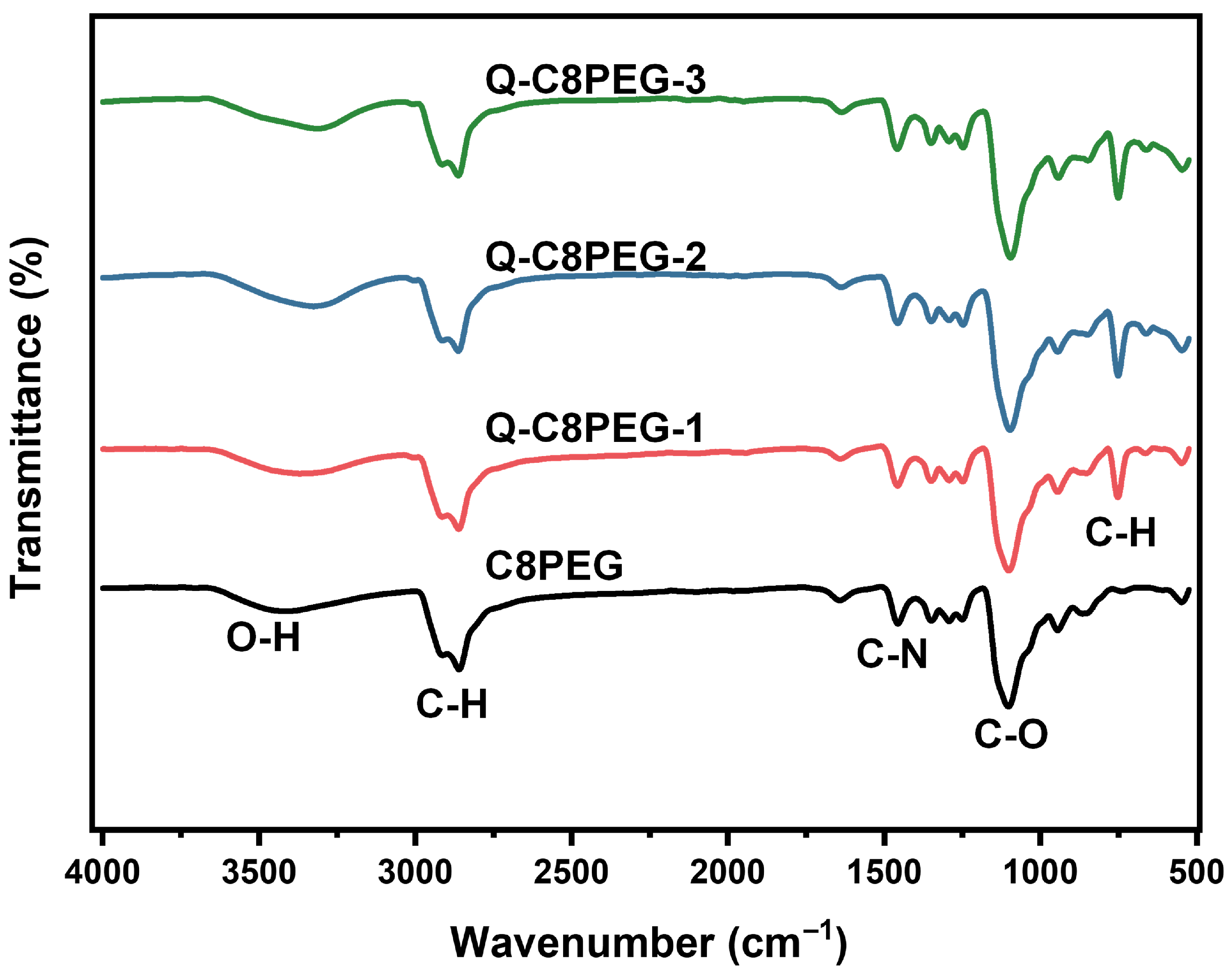

The molecular structures of the Q-C8PEG-n copolymers were further corroborated by FTIR spectroscopy. As shown in

Figure 3, based on our previous research, the broad peak at approximately 2860 cm

−1 corresponds to the stretching vibrations of alkyl C-H bonds, and the strong absorption band at 1094 cm

−1 is attributed to C-O stretching vibrations. Differently with C8PEG, the peak at 750 cm

−1 in Q-C8PEG-n is attributed to the out-of-plane rocking vibration of the methylene (CH

2) groups in the alkyl chains. This peak arises from the quaternization-induced conformational ordering of the chains [

28]. Q-C8PEG-n showed an enhancement in the peaks related to N-CH

3 at 1462 cm

−1, further confirming the successful introduction of CH

3I [

29]. These spectral changes not only validate the chemical modifications but also highlight how quaternization enhances the cationic character of the copolymers, which is crucial for their self-assembly into micelles.

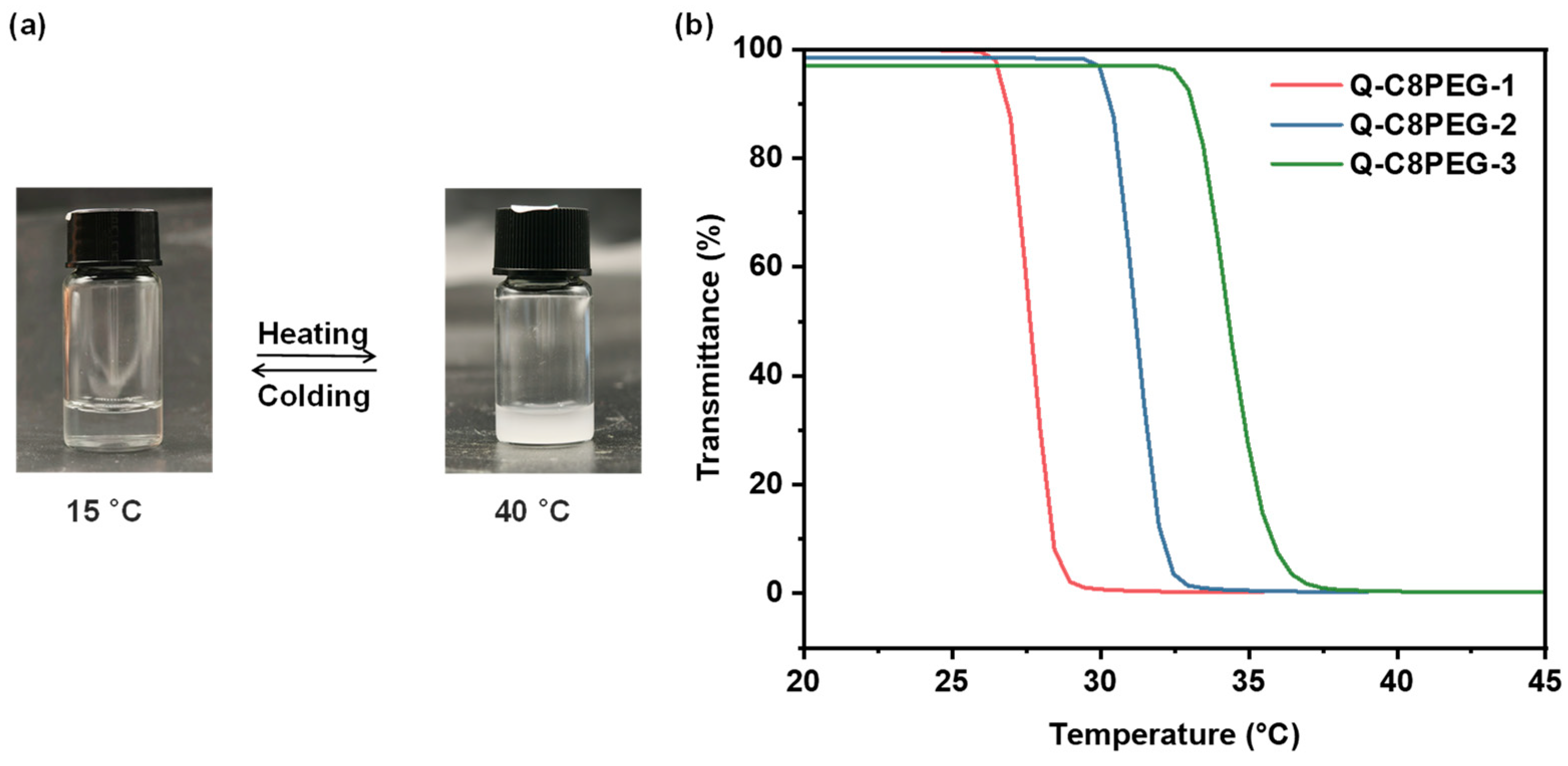

The thermoresponsiveness of the Q-C8PEG-n copolymers in aqueous solution is illustrated in

Figure 4a. At low temperatures, the polymer chains remain well-hydrated and dispersed in water, yielding a clear and transparent solution. As the temperature increases to the cloud point temperature (Tcp), the chains undergo dehydration and hydrophobic aggregation, resulting in solution turbidity and demonstrating reversible thermoresponsive behavior characteristic of lower critical solution temperature (LCST)-type polymers. To quantify these thermoresponsive properties, the transmittance of 3 wt% Q-C8PEG-n aqueous solutions at 700 nm was measured using variable-temperature UV-vis spectroscopy. Notably, the phase transition temperature of the non-quaternized C8PEG could not be determined, as it remained turbid even in an ice-water bath at 0 °C, indicating an LCST below this temperature due to its higher hydrophobicity.

As depicted in

Figure 4b, the quaternized Q-C8PEG-n copolymers exhibit enhanced hydrophilicity, rendering them clear and transparent at room temperature. Upon heating to their respective Tcp values, the solutions become turbid, with a sharp drop in transmittance. The measured Tcp values were 27.6 °C for Q-C8PEG-1, 31.3 °C for Q-C8PEG-2, and 34.4 °C for Q-C8PEG-3. This increasing trend in Tcp correlates with higher quaternization degrees, which elevate charge density and hydrophilicity, thereby requiring greater thermal energy to disrupt polymer-water interactions and induce phase separation. For Q-C8PEG-4 (fully quaternized), no phase transition was observed up to 60 °C, suggesting its Tcp exceeds practical measurement ranges due to maximal ionic hydration. Cooling the solutions back to room temperature restored clarity and transparency, confirming the reversibility of the temperature-induced phase transition. These findings align with literature on cationic thermoresponsive polymers, where quaternization enhances solubility and tunes Tcp by modulating electrostatic repulsions and hydration shells, which is critical for applications in stimuli-responsive hydrogels.

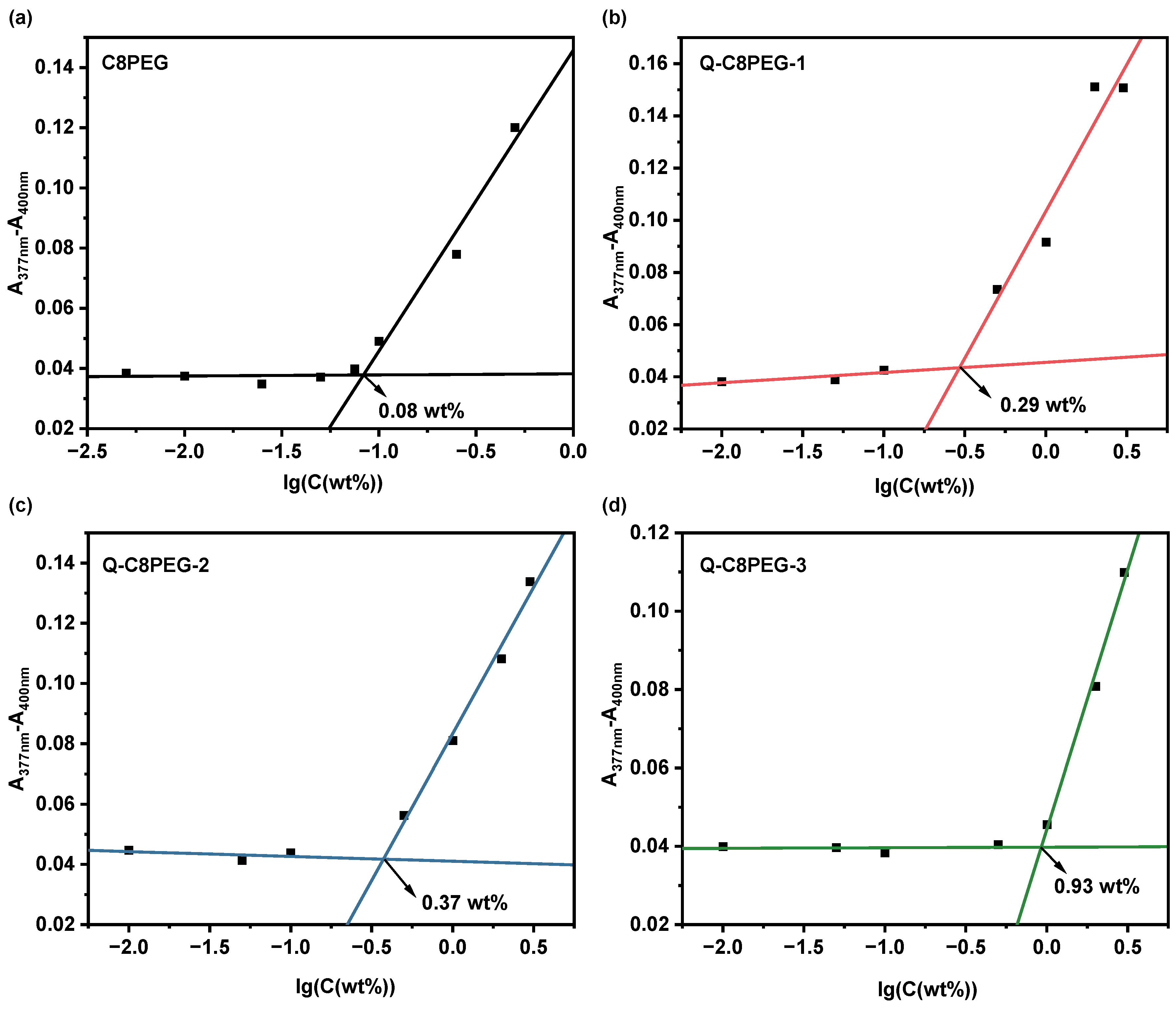

To further investigate the aggregation behavior of the polymers, the hydrophobic dye 1, 6-diphenyl-1, 3, 5-hexatriene (DPH) was employed as a fluorescent probe to determine the critical micelle concentration (CMC) of the Q-C8PEG-n copolymers [

22]. Above the CMC, the formation of hydrophobic micelle cores enables the encapsulation of DPH, resulting in a marked increase in its absorbance due to the dye’s enhanced solubility in the nonpolar environment. Conversely, below the CMC, DPH remains poorly solubilized in the aqueous phase, yielding low absorbance signals. The CMC values for C8PEG and Q-C8PEG-n were determined by plotting the absorbance at 377–400 nm against the logarithm of the polymer concentration and identifying the inflection point via linear fitting.

As shown in

Figure 5, the CMC values were 0.08 wt% for C8PEG, 0.29 wt% for Q-C8PEG-1, 0.37 wt% for Q-C8PEG-2, and 0.93 wt% for Q-C8PEG-3. Notably, no micelle formation was observed for Q-C8PEG-4 even at concentrations up to 5 wt%, indicating that full quaternization imparts excessive hydrophilicity, preventing self-assembly under these conditions. The observed increase in CMC with quaternization degree reflects the enhanced ionic character and hydration of the copolymers, which strengthens polymer-water interactions and raises the energy barrier for hydrophobic aggregation. This trend is consistent with the previously noted elevation in Tcp (

Figure 4b), where greater charge density similarly delays phase separation by promoting solubility.

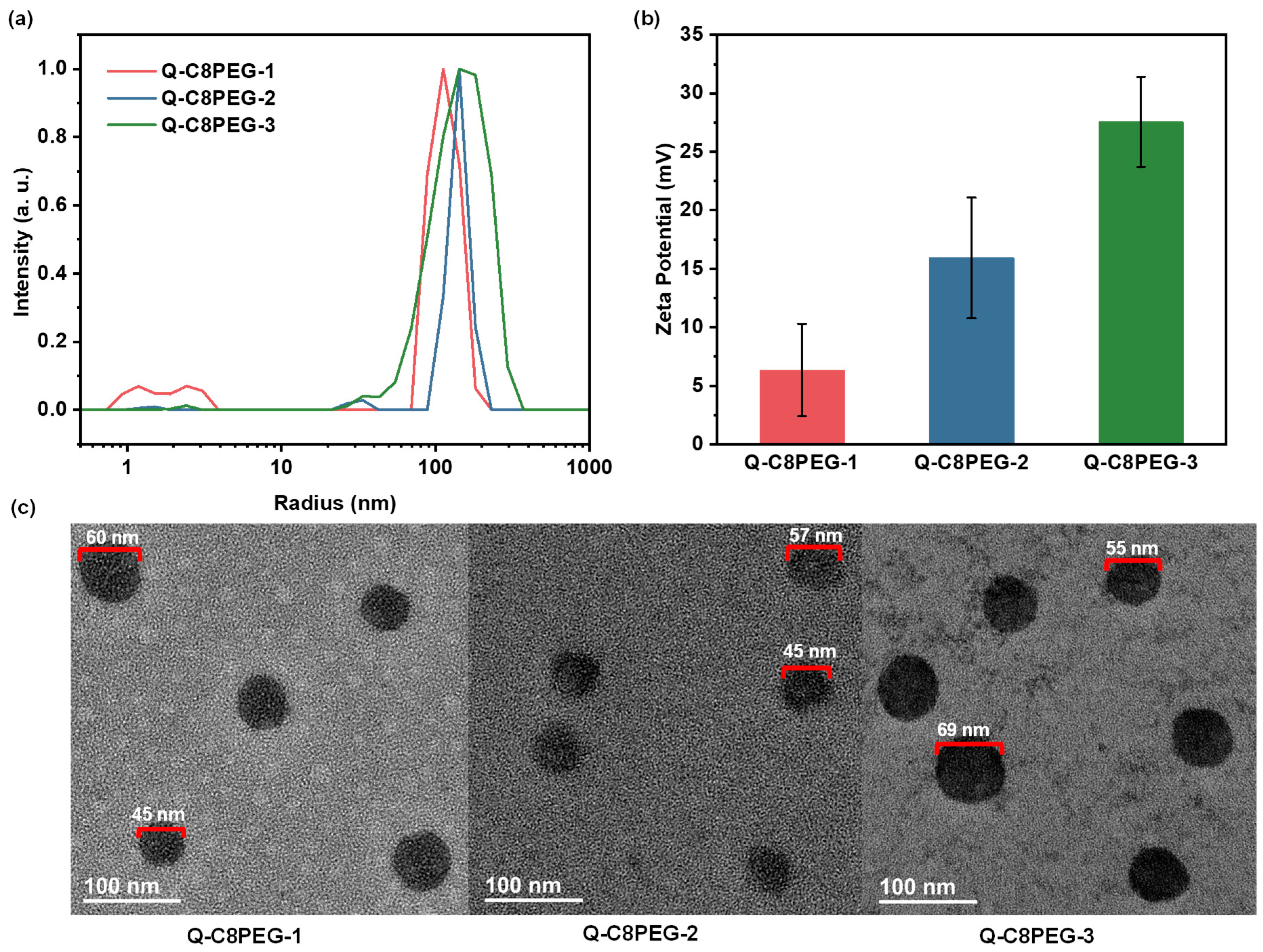

Above the CMC, at a 1 wt% concentration and 25 °C, dynamic light scattering (DLS) was utilized to assess the hydrodynamic diameters of the micelles formed by Q-C8PEG-1, Q-C8PEG-2, and Q-C8PEG-3. The results revealed average diameters of approximately 70 nm for Q-C8PEG-1, 120 nm for Q-C8PEG-2, and 126 nm for Q-C8PEG-3. This progressive increase in particle size with quaternization degree can be attributed to the formation of a thicker hydration shell around the micelles, driven by the higher density of quaternary ammonium groups, which attract more water molecules and expand the apparent volume. However, the modest size difference between Q-C8PEG-2 and Q-C8PEG-3 suggests a plateauing effect at higher quaternization levels, possibly due to balanced electrostatic repulsions that stabilize looser micellar structures. These micelle characteristics are pivotal for their role as dynamic crosslinkers in the hydrogels, where tunable size and stability influence network formation, responsiveness, and antibacterial efficacy, as quaternized groups confer cationic surfaces that disrupt bacterial membranes.

To complement the DLS measurements, transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was employed to visualize the morphology and dry-state sizes of the micelles. As shown in

Figure 6, the TEM images of micelles formed by Q-C8PEG-1, Q-C8PEG-2, and Q-C8PEG-3 revealed spherical structures with diameters in the range of 50–70 nm, which are consistently smaller than the hydrodynamic diameters obtained from DLS (70–126 nm). This size discrepancy is typical for hydrated soft nanomaterials and can be attributed to the evaporation of the surrounding hydration layer during TEM sample preparation, coupled with the low electron contrast of the extended PEG segments in the micellar corona.

Furthermore, zeta potential measurements were conducted to evaluate the surface charge of the micelles in aqueous dispersion (1 wt%, 25 °C). The values were determined to be +6.35 mV for Q-C8PEG-1, +15.9 mV for Q-C8PEG-2, and +27.6 mV for Q-C8PEG-3, exhibiting a clear positive correlation with the degree of quaternization. This trend quantitatively confirms the progressive incorporation of quaternary ammonium groups, which impart increasing cationic character to the micellar surfaces. Positive zeta potentials in this range indicate moderate to good colloidal stability through electrostatic repulsion, preventing aggregation in solution. Importantly, the enhanced positive charge density is key to the antibacterial properties of these micelles, as it promotes strong electrostatic interactions with negatively charged bacterial cell membranes (e.g., in Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria), leading to membrane permeabilization, leakage of cellular contents, and ultimately microbial death. These characteristics position the Q-C8PEG-n micelles as effective dynamic crosslinkers in the multi-responsive hydrogels, where tunable charge and size enable pH- or temperature-triggered disassembly, alongside inherent antimicrobial activity to prevent infections in biomedical applications.

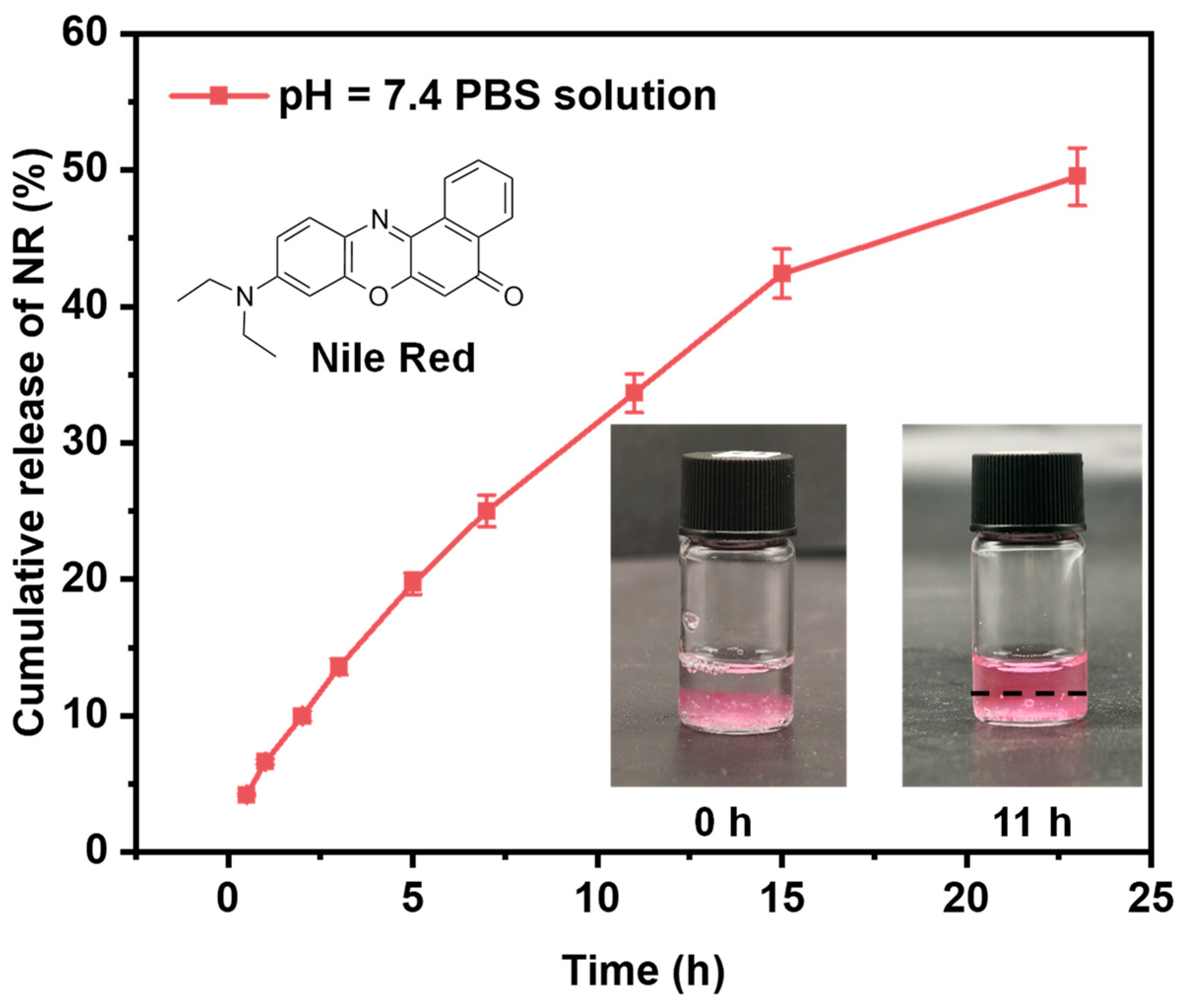

To further evaluate the self-assembly capability of the prepared copolymers and their potential as carriers for hydrophobic payloads, Nile red—a hydrophobic dye commonly used as a model for poorly water-soluble drugs—was employed to assess the drug loading content (DLC) and encapsulation efficiency (EE) in Q-C8PEG-3 micelles. Due to the hydrophobic polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon structure of Nile red, it can be encapsulated within the hydrophobic core of the micelle through physical interactions. Q-C8PEG-3 was selected for this study due to its balanced amphiphilicity, exhibiting a suitable CMC (0.93 wt%) and micelle size (~126 nm) that facilitate stable encapsulation without excessive hydrophilicity that might hinder core formation, as observed in Q-C8PEG-4. The encapsulation was performed by dissolving Nile red in a polymer solution above the CMC, followed by dialysis to remove unencapsulated dye. The standard curve of Nile red in pH 7.4 PBS solution was expressed by the equation, Y = 0.05176X + 0.08389, where X was the concentration of the Nile red solution in μg/mL and Y was the fluorescence intensity of Nile red. The R2 value of the standard curve was 0.99875, which is greater than 0.99, indicating that the regression line fits the data points. The DLC and EE of Nile red in the Q-C8PEG-3 micelles were around 0.42% and 26.78%.

2.2. Synthesis and Characterization of Hydrogel

Hyaluronic acid (HA), a naturally occurring polysaccharide renowned for its excellent biocompatibility, biodegradability, and high water retention capacity, is widely utilized in biomedical applications such as drug delivery and tissue regeneration. Leveraging the dynamic covalent chemistry of boronic ester bonds, which form between phenylboronic acid and diols and can be stabilized by intramolecular B-N coordination for enhanced stability at physiological pH, we synthesized a copolymer of HA and 3-aminophenylboronic acid (3-APBA), denoted as HA-PBA [

26]. This copolymer was prepared via carbodiimide-mediated coupling of the carboxylic acid groups on HA with the amine functionality of 3-APBA, following established protocols, and formulated as a 5 wt% stock solution in PBS (pH 7.4) for subsequent hydrogel formation with the quaternized copolymers.

The hydrogel network relies on the reversible boronic ester crosslinks between the PBA moieties on HA-PBA and the diethanolamine units in Q-C8PEG-n, where the nitrogen atom facilitates B-N coordination to lower the pKa of the boronic acid and promote bond formation under neutral conditions. However, experiments revealed that the fully quaternized Q-C8PEG-4 failed to form a stable gel with HA-PBA, as the high density of positive charges likely induces electrostatic repulsion that disrupts the B-N coordination and hinders effective crosslinking between phenylboronic acid and diols. Consequently, Q-C8PEG-3—the copolymer with the highest quaternization degree that still permits micelle formation and balanced charge density—was selected to fabricate the hydrogel sample (denoted as Gel) with HA-PBA for further characterization. This selection ensures optimal amphiphilicity for micelle-mediated crosslinking while maintaining sufficient cationic sites for antibacterial activity.

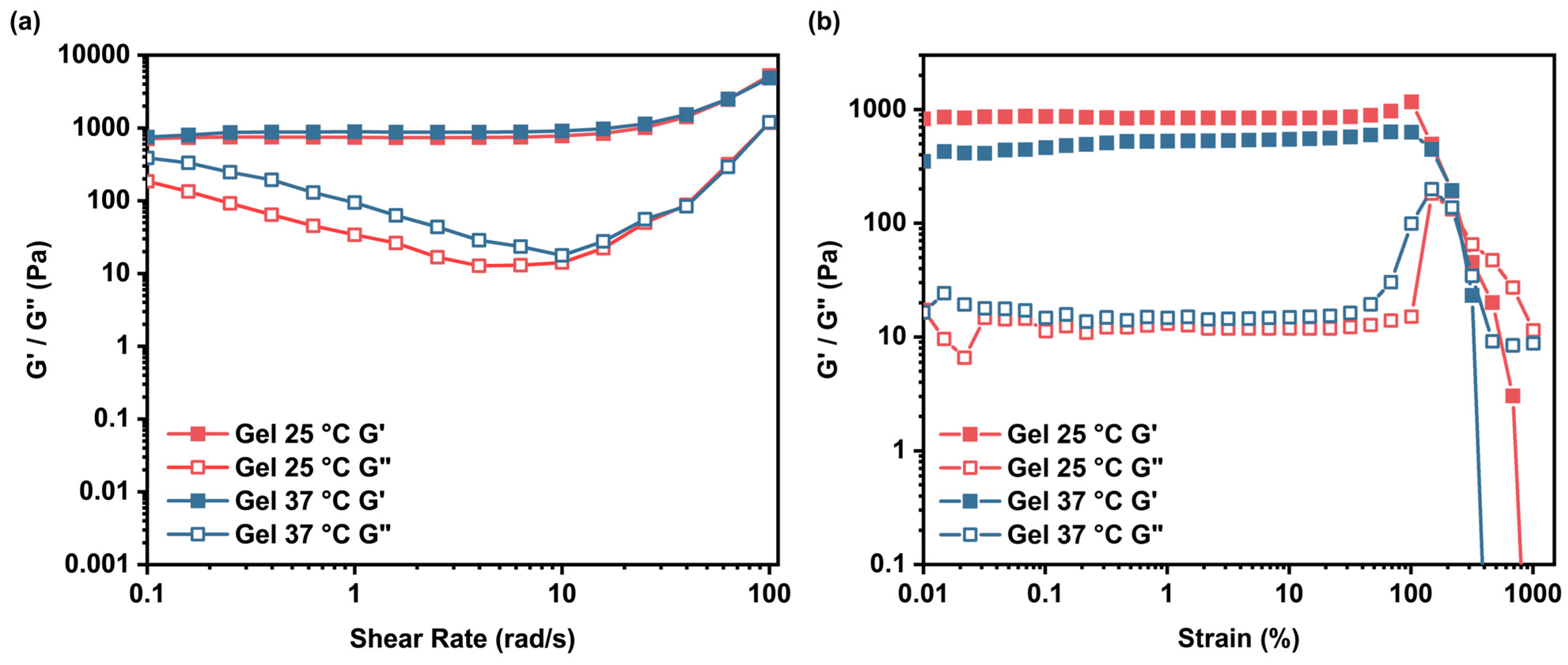

To assess the mechanical properties of the Gel, rheological measurements were conducted using a rotational rheometer. Strain amplitude sweeps (at a fixed angular frequency of 10 rad/s) and angular frequency sweeps (at a fixed strain amplitude of 0.1%) were performed at both 25 °C and 37 °C. As shown in

Figure 7, the storage modulus (G’) dominated the loss modulus (G’’) across the tested ranges at both temperatures, confirming the viscoelastic solid-like behavior characteristic of a crosslinked hydrogel network. Notably, at 37 °C, G’ exhibited a slight decrease compared to 25 °C (e.g., from ≈870 Pa to ≈460 Pa at low strain), indicating partial disruption of the internal structure due to temperature-induced weakening of the dynamic crosslinks. This thermosensitivity aligns with the LCST behavior observed in Q-C8PEG-3 (Tcp ≈ 34.4 °C), where elevated temperatures promote hydrophobic collapse of the micellar cores, leading to network softening.

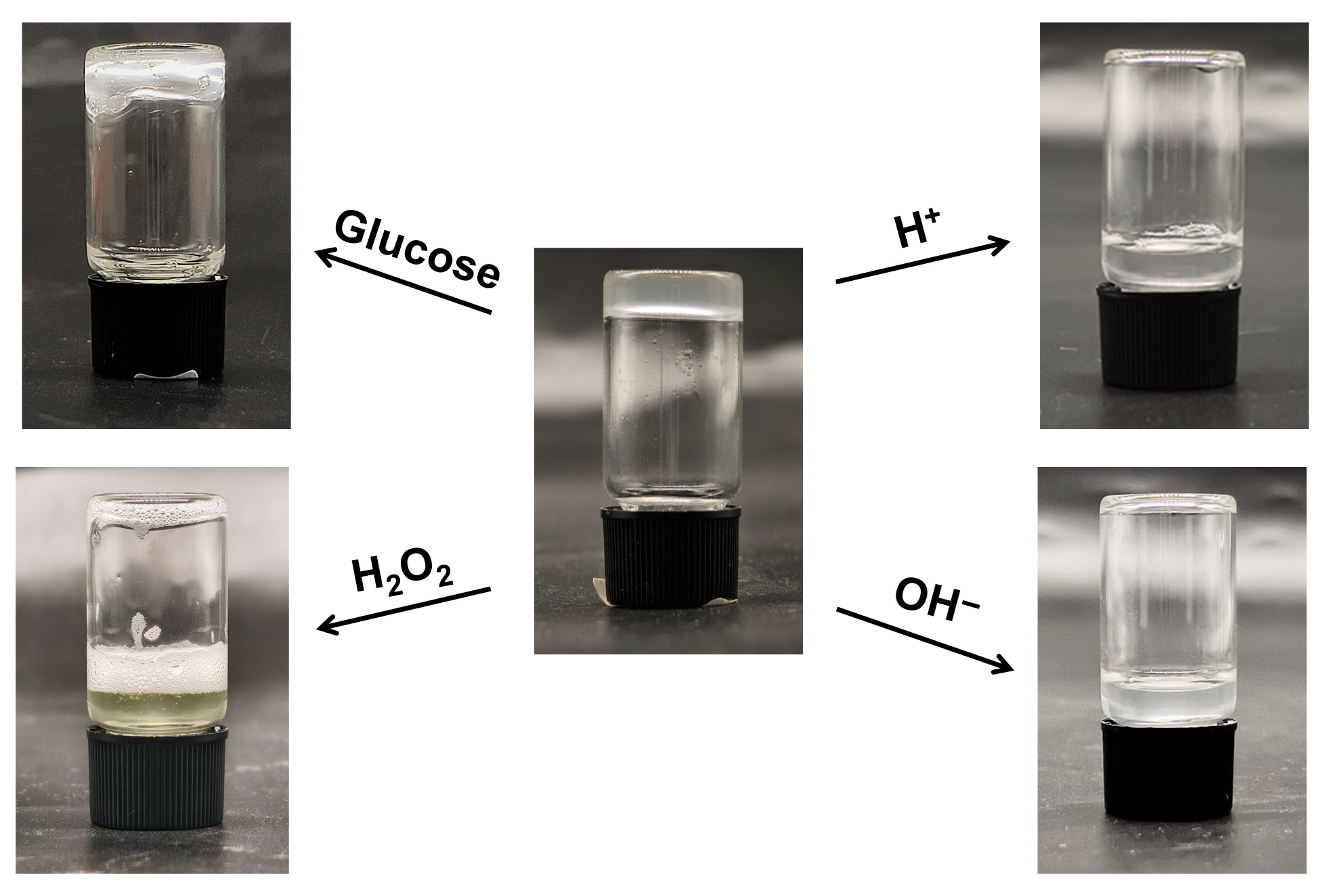

The multi-responsive nature of the hydrogel was evaluated by assessing its disruption and degradation behavior under various stimuli, focusing on pH (acidic and alkaline conditions) and glucose exposure, which are relevant to physiological environments such as wound sites or diabetic settings where pH fluctuations or elevated glucose levels may trigger controlled responses. The dynamic covalent boronic ester crosslinks in the Gel are inherently sensitive to these stimuli: in acidic media, protonation promotes hydrolysis of the boronic ester bonds, while in alkaline conditions, excess hydroxide ions can facilitate nucleophilic attack and bond cleavage. Glucose, as a competing diol, can displace the diethanolamine units from the boronic acid moieties, potentially leading to network disassembly. As shown in

Figure 8, immersion of the Gel in acidic and alkaline solutions resulted in complete degradation within 0.5 h, transforming the hydrogel into a turbid sol state due to the rapid hydrolysis of crosslinks. This swift response highlights the pH-sensitivity of the boronic ester network, enabled by the intramolecular B-N coordination in Q-C8PEG-3, which stabilizes bonds at neutral pH but allows facile dissociation under extreme pH shifts. When the hydrogel was immersed in a 3% H

2O

2 solution, it completely degraded within 0.5 h, accompanied by the solution turning yellow and vigorous gas release. This phenomenon arises from the redox reaction between I

−associated with the quaternized copolymer and H

2O

2, which generates I

2 and breaks the boronic ester. In turn, the I

2 acts as a catalyst to promote the decomposition of excess H

2O

2, resulting in the production of O

2. In contrast, exposure to a 30 mg/mL glucose solution (pH 7.4) for 0.5 h induced only minor structural weakening, manifesting as slight flow upon vial inversion without full degradation. This limited response may stem from the high stability of the B-N-coordinated boronic esters, requiring higher glucose concentrations or prolonged exposure for competitive binding to fully disrupt the network—consistent with tunable glucose sensitivity in similar systems. These behaviors underscore the hydrogel’s potential for targeted applications, such as pH-triggered drug release in acidic tumor microenvironments or controlled softening in glucose-rich diabetic wounds, while the antibacterial quaternized micelles provide an additional layer of infection resistance. The stability of the hydrogel was further evaluated by immersing it in 1 mL of various aqueous solutions, such as deionized water, PBS solution, 30 mg/mL glucose solution, and ethanol-water mixtures, at room temperature for 24 h. The results showed that the hydrogel only underwent swelling but did not dissolve (

Figure S12), demonstrating excellent water retention capacity and structural stability. This characteristic enables the hydrogel to efficiently absorb exudates from wound tissues and maintain a moist wound microenvironment, which is critical for facilitating wound healing.

The microstructure of the lyophilized Gel was characterized using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) to elucidate its internal architecture and suitability for biomedical uses.

Figure 9a, b depict the overall and magnified views, respectively, revealing a three-dimensional interconnected porous network with pore sizes predominantly in the 8–15 µm range. This porosity arises from the phase separation during micelle-mediated crosslinking and subsequent freeze-drying, where the amphiphilic Q-C8PEG-3 micelles act as templates, creating voids upon solvent sublimation. Such a microporous structure facilitates efficient nutrient diffusion, waste removal, and cell infiltration, making it ideal for tissue engineering scaffolds.

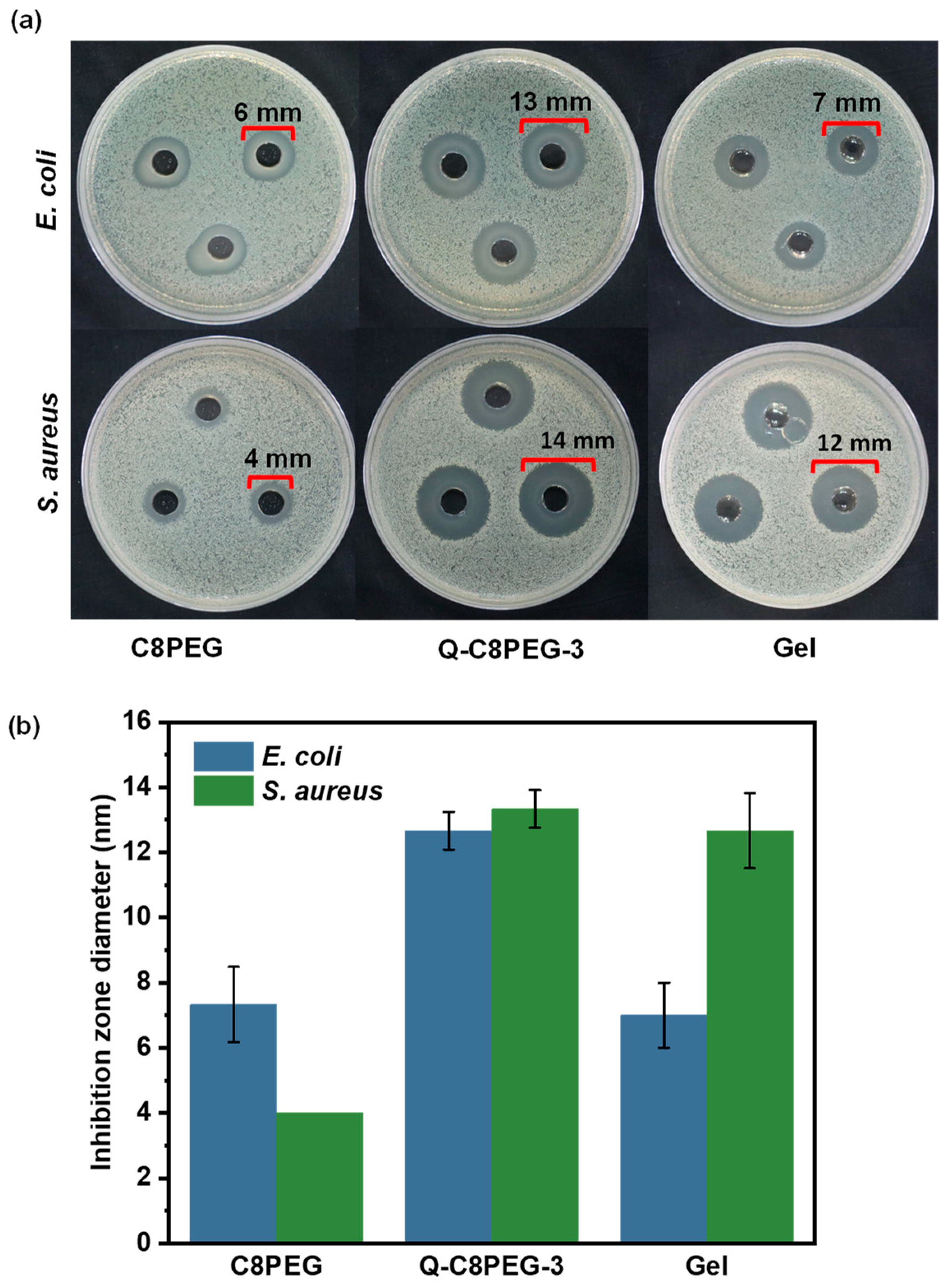

2.3. In Vitro Antibacterial Properties

Quaternized copolymers exhibit strong affinity for negatively charged bacterial cell surfaces through electrostatic interactions, leading to membrane disruption, leakage of intracellular contents, and eventual cell death. This mechanism is particularly effective against both Gram-negative (e.g.,

Escherichia coli,

E. coli) and Gram-positive (e.g.,

Staphylococcus aureus,

S. aureus) bacteria, though Gram-negative species often show slightly higher resistance due to their outer lipopolysaccharide membrane, which can impede cationic penetration [

30]. To verify the enhancement in antimicrobial performance post-quaternization, the antibacterial efficacies of C8PEG and Q-C8PEG-3 polymer solutions (at equivalent concentrations, e.g., 1 wt%) were compared against

E. coli and

S. aureus using the agar disk diffusion (inhibition zone) method. As depicted in

Figure 10, the inhibition zones expanded from 6 mm to 13 mm for

E. coli and from 4 mm to 14 mm for

S. aureus, demonstrating a substantial improvement in antibacterial activity attributable to the introduction of quaternary ammonium groups, which amplify cationic charge density and membrane-disrupting potential. This enhancement aligns with zeta potential measurements, where Q-C8PEG-3 exhibited a higher surface charge, facilitating stronger electrostatic binding to bacterial surfaces compared to the neutral or weakly charged C8PEG.

When incorporated into the hydrogel, the antibacterial efficacy was evaluated under identical conditions. The inhibition zone against E. coli was smaller for the Gel than for the Q-C8PEG-3 solution (e.g., ≈10 mm vs. 13 mm), likely due to slower diffusion of the quaternized micellar crosslinkers from the crosslinked matrix, which restricts their availability at the agar interface. In contrast, the Gel maintained robust efficacy against S. aureus (≈14 mm, comparable to the solution), suggesting that the Gram-positive bacterium’s more permeable peptidoglycan wall allows effective interaction even with matrix-bound antimicrobials. These results highlight the hydrogel’s selective antibacterial profile, with potential implications for applications in wound dressings where S. aureus is a prevalent pathogen. Overall, the quaternization not only boosts inherent antimicrobial activity but also synergizes with the dynamic covalent network to provide sustained release and localized action, reducing the risk of systemic toxicity while enhancing biocompatibility for tissue engineering.