1. Introduction

Wearable technology—smart devices and textiles worn on or integrated into the human body that combine materials, information, and electronics to collect, process and transmit feedback on biometric data [

1]—has evolved rapidly since the 1960s from simple fitness trackers to sophisticated real-time health-monitoring systems. However, traditional wearables face limitations due to mechanical rigidity and poor biocompatibility of materials such as metals and rigid polymers, which restrict body movement and physiological monitoring. Flexible wearables made from hydrogels—soft, pliable, polymer-based structures that retain fluid while maintaining structural integrity [

2,

3,

4]—offer a promising alternative, particularly as advances in artificial intelligence (AI) and the Internet of Things (IoT) continue.

Hydrogels possess several advantages for wearable applications: their high water content mimics natural tissues, enhancing biocompatibility and enabling long-term wear [

5,

6,

7]; their inherent flexibility and stretchability conform to body movements, improving comfort over rigid materials; and their natural adhesiveness [

2] eliminates the need for external adhesives, reducing allergic reactions. These properties address critical limitations in comfort, fit, and skin compatibility, positioning hydrogels as transformative materials for wearable systems.

The term “hydrogel” was first coined around 1888 by researchers such as J.M. van Bemmelen to describe colloidal gels based on organic salts [

8]. Modern hydrogels have been synthesized for over 70 years (

Figure 1a), beginning in the 1960s with the development of poly(2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate) (pHEMA) for contact lenses by Wichterle and Lim [

6,

9]. The 1970s marked a pivotal shift toward stimuli-responsive “smart” hydrogels that respond to environmental factors such as temperature and pH [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. The 1980s expanded applications to drug delivery, wound dressing, and dentistry [

15,

16], while the 1990s introduced electrically conductive hydrogels, enabling integration with electronics and biosensors [

17]. Significant breakthroughs in the 2000s included stretchable, tough hydrogels and enhanced conductivity through carbon-based nanomaterials and metal nanoparticles [

18,

19]. Since 2010, hydrogel-based wearables have accelerated, with Wang et al.’s 2012 [

20] introduction of triboelectric nanogenerators enabling energy harvesting. Recent research demonstrates applications in self-cooling fabrics, energy harvesting, self-powered sensing [

21,

22,

23,

24], and AI/IoT-integrated systems [

25,

26].

Hydrogels are increasingly explored (

Figure 1b) for flexible wearable devices and textiles due to their biocompatibility, moisture absorption, and permeability. Their biodegradability—unlike traditional wearables—reduces e-waste and environmental pollution while supporting sustainable design. Their thermal responsiveness enables smart textiles, such as temperature-regulating garments. Growing publication and citation volumes since the 2010s reflect surging interest in hydrogel-based wearables and their potential to transform wearable technology through sustainable, multifunctional innovation (

Figure 1c,d).

Despite the growing body of literature on hydrogel-based wearable technologies (

Figure 1c,d), several gaps remain. Existing reviews are largely application-specific [

27,

28,

29], focusing on areas such as bioelectronics [

30], human–machine interfaces [

5], batteries [

2,

31] and triboelectric nanogenerators [

32], rather than offering a comprehensive, interdisciplinary perspective. Even the most recent broad review [

33] concentrates on multifunctional hydrogels for wearable electronics, emphasizing electronic performance, material innovations, and device miniaturization, while paying insufficient attention to textile integration, user comfort, environmental sustainability, and the emerging role of AI and IoT. Furthermore, advanced fabrication techniques—such as 3D/4D printing, electrospinning, and microfabrication—essential for customized, skin-conforming designs are rarely addressed. A holistic approach that integrates materials science, device engineering, user experience, and sustainability is urgently needed but is currently absent from the literature.

This review fills these gaps by providing a truly interdisciplinary analysis. Unlike previous reviews that prioritize electronic performance alone, we place equal emphasis on user comfort, biocompatibility, and environmental sustainability—factors critical for long-term wearability and real-world adoption. Our work uniquely bridges hydrogel applications across both wearable devices and textiles, demonstrating seamless integration into everyday garments. It systematically examines advanced fabrication techniques enabling customizable and eco-friendly designs and explores the largely uncharted intersection of hydrogels with AI and IoT technologies. Specifically, this review highlights critical challenges in wearable devices and textiles, including performance metrics, stability, reproducibility, and target specifications. It compares conventional hydrogel performance against these target values, identifies gaps and limitations, and proposes strategies to overcome these challenges, ensuring next-generation wearables meet durability, comfort, and sustainability requirements. In addition, we comprehensively survey advancements since 2016 in hydrogel-based smart wearables—including sensors, energy storage and harvesting devices, smart fabrics, hybrid systems, and AI/IoT-enabled wearables—while analyzing unresolved issues such as mechanical durability and long-term stability. By integrating materials science, device engineering, health applications, and user-centered design, this review offers the most complete picture of hydrogel-based wearable technology to date and outlines strategic directions for sustainable, connected, and user-friendly innovations for next-generation wearables.

2. Overview of the State-of-the-Art Progress in Wearable Technologies

In recent years, wearable technologies have advanced rapidly, driven by innovations in flexible electronics, nanomaterials, and autonomous power systems, enabling continuous, real-time health monitoring through increasingly unobtrusive, multifunctional, and self-sustaining devices. These devices include activity trackers, augmented reality devices, microfluidic patches, smart fabrics, electrocardiogram and electroencephalogram devices, continuous vital sign collection (CVSC) devices, real-time glucose monitoring devices, smart rings, necklaces, contact lenses, and gloves [

34]. Notable progress has been made in wearable sensors, energy storage, energy harvesting, biosignal monitoring, and smart textiles, though critical challenges remain in performance metrics, stability, and reproducibility (

Table 1).

2.1. Wearable Sensors: Performance and Limitations

Recent progress in wearable sensors has focused on enhancing sensitivity, flexibility, stretchability, multifunctionality, and non-invasive monitoring, with emerging integration of AI and human–machine learning [

35,

36]. However, critical evaluation reveals significant variability in performance metrics and stability across different material platforms.

Advances in materials science have led to sensors with hybrid materials and structures capable of simultaneously measuring multiple parameters [

37,

38,

39,

40,

41]. Graphene–metal nanoparticle hybrids represent a particularly promising approach. Lee et al. [

41] demonstrated that doping graphene with metal nanoparticles and combining it with a gold mesh enhances electrochemical activity through synergistic effects: gold nanoparticles provide catalytic sites that improve electron transfer (achieving sensitivity of 10.93 μA/mM/cm

2 for glucose detection), while graphene increases active surface area and electron transfer kinetics. This hybrid structure achieved conductivity of approximately 10

3–10

4 S/m and demonstrated stable performance over 100 bending cycles, making it suitable for sweat-based diabetes monitoring. However, the long-term stability beyond several weeks and reproducibility across manufacturing batches remain inadequately characterized.

Yu et al. [

40] advanced this concept with a fully perspiration-powered electronic skin (PPES) featuring multimodal sensors and lactate biofuel cells utilizing zero- to three-dimensional nanomaterials. The system achieved remarkable power density (3.5 mW/cm

2) and extended operational stability (60 h continuous operation), monitoring urea, glucose, pH, and NH

4+, and skin temperature while wirelessly transmitting data via Bluetooth. Despite these achievements, critical limitations include: (1) performance degradation under varying environmental conditions (humidity, temperature fluctuations); (2) calibration drift requiring frequent recalibration; and (3) limited mechanistic understanding of ion vs. electron conductivity contributions to overall device performance. The device primarily relies on ion conductivity through sweat (typically 0.01–0.1 S/m), while the nanomaterial electrodes provide electron conductivity (1000–10,000 S/m). However, the interface between these conduction mechanisms remains a bottleneck affecting long-term reliability.

2.2. Energy Storage: Performance and Limitations

Energy storage remains a critical challenge for wearable systems, with key progress in flexible batteries and supercapacitors, yet current performance falls short of target values for extended autonomous operation.

Flexible lithium-ion and solid-state batteries offer mechanical flexibility while addressing safety concerns [

42,

43,

44]. Current flexible lithium-ion batteries achieve energy densities of 100–200 Wh/kg—significantly lower than those of rigid counterparts (250–300 Wh/kg)—and exhibit capacity retention of 70–80% after 500 cycles of repeated bending (bending radius > 5 mm). Solid-state batteries improve safety but suffer from lower ionic conductivity (0.001–0.0001 S/cm at room temperature vs. 0.01–0.1 S/cm for liquid electrolytes), limiting power delivery. Target values for practical wearable applications include energy density >250 Wh/kg, capacity retention >90% after 1000 cycles under mechanical deformation, and operational temperature range of −20 °C to 60 °C—goals not yet achieved by current flexible battery technologies.

Supercapacitors utilizing carbon nanotube yarns and conductive polymers show promise for textile integration [

45,

46,

47,

48]. Carbon nanotubes provide electrical conductivity (10

4–10

5 S/m), high specific surface area (>1000 m

2/g), and mechanical strength, while conductive polymers (e.g., PEDOT:PSS, polyaniline) enhance energy density (20–40 Wh/kg) through pseudocapacitance. Textile-integrated supercapacitors achieve power densities of 1–10 kW/kg but suffer from limited energy density (<10 Wh/kg vs. target >50 Wh/kg) and stability issues: capacitance retention typically degrades to 70–85% after 5000 cycles, and washing durability remains problematic (>30% performance loss after 10 wash cycles). Furthermore, reproducibility across different textile substrates and manufacturing processes shows high variability (±15–25% in capacitance values).

Hybrid energy storage systems combining batteries and supercapacitors address transient power demands while extending battery lifespan by 20–40% [

49,

50]. However, system complexity, increased weight (20–30% increase), and integration challenges limit practical deployment. Critical assessment reveals that current hybrid systems achieve only 60–70% of theoretical performance due to impedance mismatches and control inefficiencies.

2.3. Energy Harvesting: Performance and Limitations

Energy harvesting technologies convert ambient energy into electrical power, yet current power outputs remain insufficient for many wearable applications that require >1 mW of continuous power.

Triboelectric and piezoelectric nanogenerators harness mechanical energy from body movements [

51,

52,

53], typically generating 10–500 μW/cm

2 under normal walking conditions—adequate for ultra-low-power sensors but insufficient for wireless data transmission (which typically requires 1–10 mW). Thermoelectric generators utilizing body heat gradients face inherent limitations due to small temperature differences (typically 2–5 °C between skin and ambient) [

54], with Vashaee’s team achieving notable performance: 44 μW/cm

2 under still air and 156.5 μW/cm

2 under airflow using nanocomposite bismuth telluride materials [

55]. This represents 4–7× improvement over commercial TEGs, yet falls short of target values (>500 μW/cm

2) for continuous operation of multifunctional wearables. Critical limitations include: (1) dependence on environmental conditions (ambient temperature, airflow); (2) thermoelectric figure of merit (ZT) limited to 0.8–1.2 for flexible materials vs. >2.0 for optimal performance; and (3) thermal contact resistance degradation over time (10–20% performance loss after extended wear).

Biofuel cells generating electricity from sweat or blood offer attractive power densities (1–5 mW/cm

2 from sweat lactate) [

56,

57], as demonstrated by Caltech’s hybrid e-skin [

58]. However, critical challenges include: (1) enzyme stability (50–70% activity loss within 1–2 weeks); (2) dependence on metabolite availability (requiring physical activity for sweat production); (3) biocompatibility concerns for implantable variants; and (4) reproducibility issues stemming from batch-to-batch enzyme variability (±20–30%).

2.4. Biosignal Monitoring and Smart Textiles: Performance and Limitations

Continuous biosignal monitoring (electrocardiography (ECG), electromyography (EMG), electroencephalography (EEG), and photoplethysmography (PPG)) has advanced with dry electrodes and tattoo-like sensors, yet signal quality and long-term stability remain critical concerns. Dry electrodes achieve skin-electrode impedance of 10–100 kΩ (vs. 1–10 kΩ for wet electrodes), resulting in signal-to-noise ratios 5–10 dB lower than those of clinical-grade systems [

59,

60,

61]. AI-enhanced signal processing partially compensates, but motion artifacts and electrode drift necessitate frequent recalibration (every 2–4 h during continuous monitoring). Target impedance values < 10 kΩ and stability > 24 h without recalibration remain unmet.

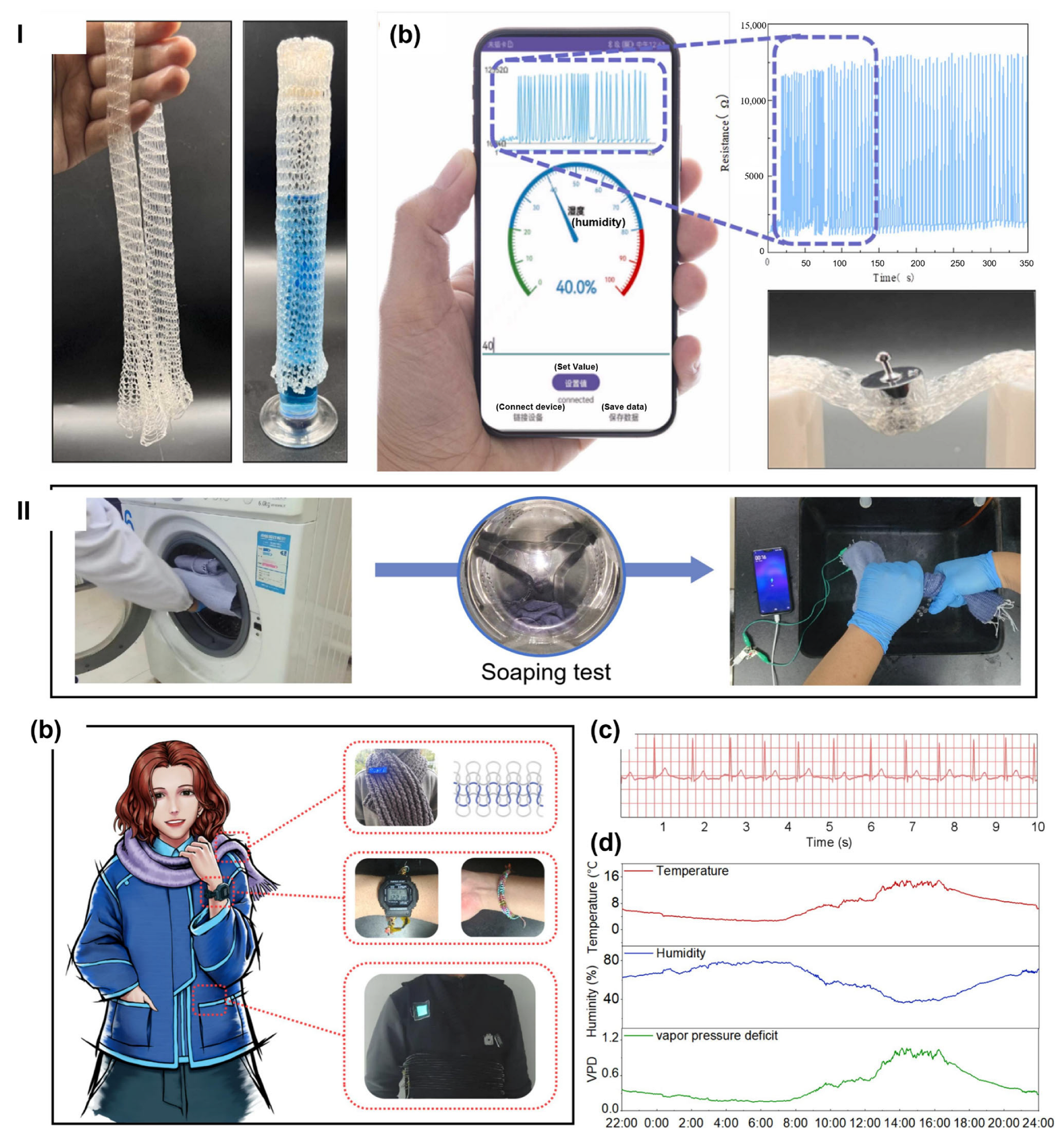

Smart textiles integrating conductive yarns, embroidered circuits, and printed electronics [

62,

63,

64,

65] enable seamless body integration. Conductive yarns achieve resistivity of 0.01–0.1 Ω·cm (silver-coated) to 10–100 Ω·cm (carbon-based), but washing durability poses challenges: conductivity typically degrades 20–50% after 10–20 wash cycles. E-textiles incorporating energy storage, sensing, and communication demonstrate multifunctionality but suffer from: (1) limited mechanical durability (failure after 500–1000 stretch cycles at 30% strain); (2) breathability reduction (30–50% decrease in moisture vapour transmission rate); and (3) manufacturing complexity limiting scalability and reproducibility.

2.5. Critical Challenges and the Need for Hydrogel Integration

Despite impressive progress, modern wearable technologies face persistent limitations: limited battery life (1–7 days for continuous monitoring vs. target >30 days), poor skin adhesion (especially under sweating and motion), user discomfort from rigid materials, high costs (US

$100–US

$500 per device vs. target <US

$50 for widespread adoption), and restricted functionality [

2,

34,

66]. Critically, insufficient characterization of long-term stability (>3 months), reproducibility across manufacturing batches (typically ±15–30% variability), and mechanistic understanding of failure modes hinder clinical translation. These challenges underscore the need for more research, particularly interdisciplinary research, to bridge the gaps and advance wearable technology, including the exploration of new sustainable materials.

Table 1.

State-of-the-art performance metrics for wearable technologies and target values.

Table 1.

State-of-the-art performance metrics for wearable technologies and target values.

| Technology | Key Metrics | Current

Performance | Target Values | Primary

Limitations | Ref. |

|---|

| Graphene–metal hybrid sensors | Sensitivity; Conductivity; Stability | 10.93 μA/mM/cm2; 1000–10,000 S/m; >100 cycles | >50 μA/mM/cm2; >10,000 S/m; >1000 cycles | Long-term drift; batch variability, ion/electron interface | |

| Flexible Li-ion batteries | Energy density; Cycle retention; Temp. range | 100–200 Wh/kg; 70–80% after 500 cycles; 0–40 °C | >250 Wh/kg; >90% after 1000 cycles; −20 to 60 °C | Mechanical degradation, electrolyte stability | [42,43,44] |

| Solid-state batteries | Ionic conductivity; Safety | 0.0001–0.0010 S/cm; High >0.01 S/cm; High | Low ionic conductivity at room temperature; interface resistance | | |

| Textile supercapacitors | Energy density; Power density; Wash durability | <10 Wh/kg; 1–10 kW/kg; 70% after 10 washes | >50 Wh/kg; >5 kW/kg; >90% after 50 washes | Low energy density, washing-induced degradation, reproducibility | [45,46,47,48] |

| Thermoelectric generators | Power density; ZT value | 44–156 μW/cm2; 0.8–1.2 | >500 μW/cm2; >2.0 | Small temperature gradients, thermal contact resistance, ambient dependence | [54,55] |

| Biofuel cells | Power density; Enzyme stability | 1–5 mW/cm2; 50–70% after 1–2 weeks | >5 mW/cm2; >80% after 1 month | Enzyme degradation, metabolite availability, reproducibility | [56,57] |

| Dry electrodes (biosignals) | Impedance; SNR; Stability | 10–100 kΩ; 5–10 dB lower than wet; 2–4 h | <10 kΩ; Equivalent to wet; >24 h | Motion artifacts, drift, contact quality | [59,60,61] |

| Conductive yarns (e-textiles) | Resistivity; Wash durability | 0.01–100 Ω·cm; 50–80% after 10–20 washes | <0.01 Ω·cm; >90% after 50 washes | Washing degradation, mechanical failure, breathability reduction | [62,63,64,65] |

2.6. Hydrogels as a Strategic Solution

Hydrogels—hydrophilic, crosslinked polymer networks with high water content (typically 70–95 wt% [

67])—offer strategic advantages in addressing multiple wearable technology limitations. Their mechanical properties (Young’s modulus: 1–100 kPa) match those of human skin (4–20 kPa), facilitating conformal contact and reducing mechanical irritation. Ionic conductivity (0.01–0.1 S/m for salt-containing hydrogels) enables bioelectronic interfacing, while functionalization with carbon nanotubes or metal nanowires can enhance conductivity to 1–10 S/m [

68,

69,

70,

71]. Self-healing capabilities (recovery of 80–95% of mechanical properties within minutes to hours) and stimuli-responsiveness (e.g., thermoresponsive swelling/deswelling within 10–60 s) enable dynamic sensing and integrated drug delivery [

72,

73,

74].

However, critical limitations must be acknowledged: (1) water loss: dehydration under ambient conditions (30–50% water loss within 24 h without encapsulation) compromises mechanical and electrical properties; (2) mechanical durability: fracture strain typically 100–500% vs. target >1000% for extreme body movements; tensile strength 10–100 kPa vs. target >500 kPa for robust wearables; (3) long-term stability: degradation of crosslinked networks over weeks to months, particularly under cyclic loading and varying pH/temperature; (4) reproducibility: hydrogel properties highly sensitive to synthesis conditions (gelation time, crosslinker concentration, temperature), resulting in batch-to-batch variability of ±10–20%; and (5) electron vs. ion conductivity trade-off: while hydrogels naturally support ion conductivity, achieving high electron conductivity (required for electronics interfacing) often compromises mechanical properties and biocompatibility.

Despite these limitations, hydrogels present a promising pathway for next-generation wearables.

Section 3 and

Section 4 detail hydrogel synthesis, properties, types, and recent advancements in hydrogel-integrated wearable systems, critically evaluating their performance against the target metrics outlined in

Table 1 and assessing strategies to overcome current limitations in stability, reproducibility, and multifunctional integration. Collectively, these developments demonstrate the potential of hydrogels as a game changer for next-generation wearable devices, offering enhanced biocompatibility, mechanical adaptability, and functional integration for continuous, non-invasive health monitoring.

Noteworthy is that this review focuses on hydrogels, which differ from other gels. Hydrogels are three-dimensional (3D) crosslinked polymer networks with water as the continuous phase, characterized by high water content, which makes them highly biocompatible and suitable for direct skin-contact applications. In contrast, organogels contain organic solvents rather than water as the continuous phase, offering enhanced permeability for the delivery of materials (e.g., drugs) through lipophilic pathways and different mechanical properties suited to specific applications. Ionogels are gel systems in which ionic liquids serve as the continuous phase, enabling high ionic conductivity and electrochemical stability for bioelectronic and energy storage applications. These distinctions are critical when selecting materials for specific wearable applications: hydrogels excel at mimicking biological tissue properties and providing aqueous ion transport pathways, organogels enable enhanced small-molecule penetration for topical therapeutics, and ionogels facilitate high-speed electron transport for electronic applications.

3. Hydrogels—Synthesis, Properties and Types Explored for Wearable Technology

Hydrogels are typically soft, pliable, 3D polymer networks that absorb and retain fluids yet maintain their structural integrity. Crosslinking within the hydrogel network provides these 3D network structures and prevents dissolution when exposed to fluids [

75]. Various components and techniques have been explored in the synthesis of hydrogels.

3.1. Hydrogel Synthesis

The synthesis process of a hydrogel significantly influences its structure, properties, and potential target applications. Understanding this relationship requires an in-depth knowledge of chosen synthesis methods. Hydrogels typically consist of polymers, crosslinkers, diluents, and/or initiators. They can be made from natural polymers (e.g., cellulose, chitin, hyaluronic acid, gelatin, agar, starch, alginate) or synthetic polymers (e.g., polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), polyacrylamide, polyethylene glycol (PEG)) [

76,

77]. Synthetic polymers are low in biodegradability and can release toxic substances into the environment, while natural polymers lack mechanical strength, require sterilization, and pose challenges for loading materials into the hydrogel cavity. The crosslinkers, which can be chemical (e.g., carboxylic acids, aldehydes) or physical (e.g., heat, ionic interactions), form bonds between polymer chains, creating a gel network. However, some chemical crosslinkers, like glutaraldehyde, have high toxicity [

77]. Natural polymers are recently being explored to promote green processes [

6]. Diluents, such as water and other solvents, control the rate of polymerization, and initiators, such as free radicals, UV light, or redox systems, trigger polymerization.

Hydrogel synthesis steps involve selecting materials based on the desired hydrogel performance and properties, adding initiators to the polymer, and crosslinking. Crosslinking is crucial in hydrogel synthesis, as it affects key microstructural parameters, physicochemical properties, and end performance. The main crosslinking techniques are physical crosslinking, exploring techniques such as hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic interactions, electrostatic interactions, metal coordination, π-π stacking, crystallization, and intermolecular entanglement under certain conditions (

Figure 2I); chemical crosslinking using techniques such as free-radical polymerization, condensation reactions, “click chemistry”, enzymatic reactions, irradiation and photopolymerization [

78,

79,

80] (

Figure 2II) or a combination of physical or chemical crosslinking mechanisms using multi-crosslinking techniques. Hydrogel crosslinking mechanisms, as well as fabrication techniques explored for wearables, are summarized below. The polymer–crosslinker mixture is then allowed to polymerize via bulk, solution, or suspension techniques, with solution processing preferred for better control of polymerization heat and industrial applicability. After polymerization, the sample is purified by washing with water or solvents to remove unreacted components or by-products, then dried using freeze-drying or vacuum drying. Lyophilization may be used before vacuum drying to remove water via sublimation, enhancing the porous structure. Finally, the crosslinked polymer network is hydrated to form the final hydrogel. The dried hydrogels can take various forms, including powders, particles, films, foams, beads, microspheres, patches, injectable liquids, and emulsions [

6,

81,

82]. Details on hydrogel crosslinking strategies have been reviewed [

80,

83,

84].

3.1.1. Physically Crosslinked Hydrogels

Physical crosslinking is the formation of supramolecular hydrogels without the use of a crosslinking agent or external force. It utilizes non-covalent bonding interactions, such as ionic interactions, hydrogen bonds, crystallization, hydrophobic interactions, and other weaker physical forces, in the polymer network under certain conditions to form the hydrogel’s 3D network. Physical crosslinking can create either strong, permanent bonds (such as those found in glassy nodules or double and triple helices) or weak bonds that are reversible, breakable, reformable, or easily disrupted by stress or changes in physical conditions. Non-covalent bonding interactions are generally reversible, forming transient linkages. It is also linked to unstable, uncontrollable dissolution, difficulty in controlling hydrogel pore size, low mechanical resistance, and the formation of free chain ends or chain loops [

85]. Physical crosslinking is influenced by various parameters, including polymer concentration, the molar ratio of each polymer, the type of solvent, the temperature of the solution, and the interaction between polymer functionalities. The amount and intensity of physically crosslinked interactions determine the mechanical properties (e.g., toughness and flexibility) of the hydrogel. The reversible non-covalent bonding of physically crosslinking hydrogels and their response to external stimuli enable their exploration for biodegradability, self-healing, and injectability at ambient temperatures.

Ionic Interactions

In ionic/electrostatic interactions, non-covalent bonds are formed between oppositely charged groups or metal–ligand interactions. The presence of counterions creates charged interactions that influence the hydrogel crosslinking. Polyanionic polymers and polycationic polymers are complexed to form hydrogels through complex coacervation [

83], which exhibit rapid environmental response and self-healing properties. Coacervation is induced by modifications in pH, ionic strength, temperature, or solubility of the hydrogel media environment under controlled conditions.

Hydrogen Bonding

Hydrogen bonding is a widely used technique for crosslinking polymers containing polar functional groups, such as –OH and –COOH groups. When –COOH groups protonate in the presence of other polymers containing electron-deficient hydrogen atoms, hydrogen bonds can be formed [

84]. In aqueous polymer systems with –COOH groups, hydrogen bonds form when pH is lowered. Acidic conditions reduce solubility, enabling hydrogen bonding. Natural polymers are largely explored for hydrogen bonding. Natural polymers (e.g., cellulose, chitosan, gelatin, and protein) contain abundant –OH and –COOH functional groups, which can interact with functional groups of other hydrogel components to produce hydrogen bonds.

Crystallization

The crystallization technique involves repeatedly freezing and thawing, during which amorphous and crystalline regions form within the hydrogel. The amorphous regions form when free water molecules occupy junctions or voids in the phase-separated material, while the crystalline regions form due to the aggregation of crystallites. The crystallites within a polymer chain can serve as physical crosslinking sites, facilitating the formation of hydrogels. A common polymer used for crosslinking via crystallization is polyvinyl alcohol (PVA). Crosslinking occurs at a temperature within the freezing range. The hydrogel properties, especially mechanical properties, are controlled by carefully tuning the degree of crosslinking between molecular chains or crystallinity of crystals during repeated freezing and thawing.

Hydrophobic Interactions

This is typically applied to water-soluble polymers incorporating hydrophobic groups or monomers, with thermal and ultrasonic processes aiding the formation of hydrophobic associations.

3.1.2. Chemically Crosslinked Hydrogels

Chemical crosslinking refers to the formation of hydrogels through the use of a crosslinking agent to connect polymer chains within a polymer network, involving direct interactions between linear or branched polymers. It utilizes techniques such as free-radical polymerization, “click chemistry” (e.g., Diels–Alder, Schiff base, oxime, Michael-type addition, and boronate ester), and irradiation (gamma ray or electron beam) [

78,

79]. Initiators are also added to trigger the polymerization process. Chemical crosslinking enables the interaction of the functional groups (such as OH, COOH and NH

2) with the selected crosslinking agent. Strong bonds are typically formed due to the permanent covalent bonds that are created between polymer chains, replacing hydrogen bonds with stable covalent bonds. Hence, chemically crosslinked hydrogels often exhibit improved mechanical stability, softness, and flexibility, as well as spatial and temporal control during gelation [

6,

86], compared to physically crosslinked hydrogels. However, most conventional hydrogels synthesized via chemical crosslinking contain toxic compounds as linking agents that can detach from the hydrogel during application or interact with loaded materials within the hydrogel. Chemical crosslinking is influenced by various parameters, including the type and concentration of monomer and crosslinker, solvent, reaction conditions employed, and exposure to heat, light, or an electron beam.

Free-Radical Polymerization

Free-radical polymerization is a common technique for synthesizing chemically crosslinked hydrogels. In this technique, vinyl monomers/polymers are polymerized and crosslinked with a crosslinking agent and initiators. The mechanical properties of the hydrogels are tuned by controlling monomer-to-crosslinker molar ratios. The most common monomers used include acrylic acid, acrylamide, and composite monomers containing natural macromolecules such as protein, gelatin, and chitosan [

80]. Heat, light, radiation, and electron beams are applied to initiate free-radical polymerization.

Click Chemistry

“Click chemistry”, coined by Barry Sharpless, is commonly adopted to synthesize chemically crosslinked hydrogels with self-healing properties. Click reactions combine a C atom with a heteroatom X to form a C-X-C bridge to link polysaccharides, proteins or nucleic acids [

84]. It includes Diels–Alder reaction, Borate ester bonds, Schiff base bonds, and Michael-type addition reaction. The Diels–Alder reaction yields hydrogels through the cycloaddition of dienes and/or dienophilic reagents, inducing complementary moieties for crosslinking. The Diels–Alder reaction produces no by-products or side reactions and requires neither a crosslinker nor an initiator. Due to its high atom efficiency, the lack of need for catalysts or initiators and its ability to proceed under mild conditions, it is considered an environmentally friendly technique for hydrogel synthesis [

86,

87]. Borate ester bonds are reversible covalent linkages formed via the condensation of boric acid or its derivatives with cis-diols. Hydrogels incorporating these bonds demonstrate rapid gelation, self-healing properties, and responsiveness to pH, temperature, and degradation [

88,

89]. Schiff base bonds arise from reactions between aldehyde- or ketone-containing compounds and amine-containing species, encompassing imine, hydrazone, and oxime linkages [

90]. Hydrogels based on Schiff base chemistry typically exhibit pH sensitivity [

90,

91]. The oxime crosslinking produces hydrogels from reactions between the aminoxyl/hydroxylamine group and an aldehyde/ketone. Michael-type addition reactions enable the effective coupling of nucleophiles (Michael donors) with electron-poor olefins or alkynes (Michael acceptors) to create hydrogels [

84]. It typically involves base-catalyzed addition of nucleophilic reagents (Michael donors, e.g., enolates, amines, thiols and phosphines) to active α, β-unsaturated carbonyl molecules (Michael acceptors, e.g., vinyl sulfones, acrylates, acrylonitrile and maleimides).

Irradiation

Irradiation is a versatile technique for hydrogel crosslinking that utilizes high-energy sources, e.g., gamma rays and ultraviolet (UV) light, to initiate polymer network formation. This process generates free radicals within polymer chains or monomer solutions, forming covalent bonds and a stable three-dimensional hydrogel matrix. Irradiation can proceed without the use of chemical initiators or crosslinking agents [

78], thereby reducing the risk of cytotoxicity—a crucial consideration for applications involving direct skin contact. The extent of crosslinking can be precisely modulated by adjusting parameters such as radiation dose and exposure time, enabling tuning of key hydrogel properties (e.g., mechanical strength, swelling, and electrical conductivity). These tunable characteristics are particularly beneficial for wearable technologies, where hydrogels are required to exhibit flexibility, durability, and biocompatibility. When combined with conductive fillers, irradiation-crosslinked hydrogels can also support electronic functionality, making them ideal for use in biosensors, strain gauges, and epidermal electronics. Moreover, irradiation could enable the direct integration of hydrogel functionalities onto or within fabric substrates, creating hybrid materials that respond dynamically to environmental or physiological stimuli. For example, UV or gamma irradiation can be employed to graft hydrogel networks onto textile fibers, imparting properties such as moisture responsiveness, thermal regulation, flame resistance, or controlled drug release [

92]. This approach supports the development of smart garments for medical, athletic, or protective applications. Furthermore, the non-thermal nature of irradiation preserves the structural integrity of delicate textile materials while enabling spatial control over crosslinking. This enables the fabrication of textiles with localized sensing or actuation capabilities, such as pH-sensitive drug delivery zones or temperature-responsive ventilation panels. The resulting materials offer multifunctionality and adaptability, positioning irradiation-crosslinked hydrogels as a cornerstone in the advancement of next-generation wearable and textile-based systems.

3.1.3. Multi-Crosslinked Hydrogels

With the growing demand for advanced hydrogel applications, single-mode physical or chemical crosslinking often fails to meet performance requirements. Consequently, multi-crosslinking strategies have emerged, integrating one or more physical and/or chemical crosslinking mechanisms to enhance the functional properties of hydrogels [

93,

94,

95,

96,

97,

98]. Physically crosslinked hydrogels offer excellent biocompatibility, while chemically crosslinked ones provide superior mechanical strength. Their combination yields hybrid crosslinked hydrogels with improved toughness, elasticity and self-healing properties.

3.1.4. Fabrication Techniques Employed for Optimizing Hydrogel Performance

Fabrication techniques such as three-dimensional (3D)/four-dimensional (4D) printing, electrospinning, and microfabrication have been employed to develop hydrogels with tailored properties that meet the specific needs.

3D or 4D printing: Three-dimensional (3D) printing method involves extruding a hydrogel precursor through a nozzle to fabricate structures layer by layer. It enables rapid prototyping, fabrication of complex geometries, and compatibility with a wide range of hydrogel materials. The grid-like microstructure of 3D-printed hydrogel sensors enhances their sensitivity. Such printed hydrogels have been widely investigated for wearable sensing applications [

99,

100,

101,

102,

103,

104], where hydrogels are embedded with conductive materials and printed into flexible sensors for health monitoring. For example, Ren et al. [

99] prepared a sodium alginate/sodium polyacrylate/layered rare-earth hydroxide (LRH) nanocomposite hydrogel through ionic and coordination crosslinking, which was subsequently used as a 3D printing ink to produce intricate, highly precise structures. The hydrogel exhibits excellent 3D printing performance at room temperature and tunable fluorescence emission, with potential applications in sensing. Hao et al. [

101] prepared a skin-inspired hydrogel using PVA, sodium alginate, glycerol and silver nanowires and fabricated it into complex structures (e.g., dumbbells, multilayer rectangular squares and grid structures), exploring 3D printing as a method. The 3D-printed hydrogel exhibits high tensile strength, excellent recovery and fatigue resistance under yield strain. It can also be used for detecting human motion signals. Wu et al. [

102] developed a multifunctional hydrogel suitable for digital light processing (DLP)-based 3D printing in wearable sensing applications. By incorporating both physical and chemical crosslinking networks using polymers such as poly(acrylamide), poly(acrylic acid), poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate, silk fibroin, and glycerol, the hydrogel achieved superior mechanical strength, remarkable adhesion (maintained even after 10 days of storage), and excellent water retention. The resulting sensor demonstrated a gauge factor of 1.29 under tensile strains from 1% to 100%, along with a stable relative resistance change across 80 cycles.

Four-dimensional (4D) printing refers to creating 3D-printed structures—often regarded as smart, adaptable materials—that can respond predictably to external stimuli such as heat, moisture, pH, light, water, and magnetic or electric fields [

100]. Compared with conventional 3D printing, it offers notable benefits, including greater design flexibility, accelerated production, reduced costs and material waste, and a streamlined one-step manufacturing process. Innovative materials employed for 4D printing include polymers with excellent mechanical and functional properties, such as polylactic acid, polycaprolactone and polyethylene glycol, ceramics and alloys. Some printing techniques explored include inkjet printing and stereolithography. Inkjet printing utilizes droplets of hydrogel precursor that are deposited onto a substrate. It is suitable for creating fine features and patterns. Stereolithography (SLA) involves the use of light to polymerize a hydrogel precursor layer in a layer-by-layer process. SLA offers high resolution and precision, making it ideal for creating detailed microstructures. Discussions on 3D/4D printing of soft materials, including hydrogels and the printing techniques explored, are available [

105,

106].

Electrospinning: This involves applying a high voltage to a polymer solution to create a jet that solidifies into fine fibers (diameters ranging from nanometers to micrometers) as it travels toward a grounded collector. The choice of polymer solutions and additives for electrospinning is important. The choice of polymer and solvent affects the fiber morphology and mechanical properties. Common polymers include polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) and polycaprolactone (PCL). Incorporating additives such as nanoparticles and bioactive agents into the polymer solution can enhance the functionality of the electrospun fibers. Electrospinning has been explored to develop hydrogel-based smart wearable textiles. Electrospun hydrogel fibers have been woven into fabrics to create moisture-wicking and breathable textiles. Due to their significant surface area and porosity, electrospun fibers are attractive for wearable devices that deliver functional agents.

Microfabrication: Among microfabrication techniques explored for wearables are photolithography and soft lithography. Photolithography involves coating a substrate with a light-sensitive photoresist, exposing it to light through a mask, and developing the exposed areas to create micro-scale patterns. It has been used to create microfluidic devices and sensors with precise control over the hydrogel microstructure. Soft lithography, including microcontact and replica moulding, involves creating a mould from a master pattern and using it to shape the hydrogel precursor. Soft lithography is suitable for creating flexible and stretchable electronics.

3.2. Hydrogel Properties Essential for Smart Wearable Devices and Textiles

The integration of wearable devices and textiles with the human body necessitates materials that can simultaneously meet the demands for functional performance and physiological compatibility. As wearable technologies evolve toward continuous, real-time health monitoring and therapeutic applications, the interface between the wearable and the skin becomes increasingly critical. Materials used in this interface should be soft, conformable, and biocompatible while also supporting advanced functionalities such as sensing, actuation, and data transmission. Hydrogels stand out among candidate materials for their unique blend of mechanical flexibility, chemical versatility, and biocompatibility. This section outlines the key hydrogel characteristics relevant to wearable technologies, distinguishing between inherent properties—those naturally arising from the hydrogel’s structure—and engineered or enhanced properties—those introduced through material modification or composite design. Inherent properties include flexibility and stretchability, wet adhesion, biocompatibility, skin conformability, permeability, and, in many cases, optical transparency. Engineered properties include electrical conductivity, self-healing, tunable mechanical properties, and stimuli-responsiveness, which expand their functional scope, allowing them to serve as active components in smart wearables.

Flexibility and stretchability: This is the ability of a material to bend, twist, or elongate without breaking. Hydrogels exhibit high deformability, allowing them to stretch, bend and twist in response to body movements without mechanical failure. The flexibility and stretchability of hydrogels are attributable to their loosely crosslinked polymer networks, which are swollen with water, allowing polymer chains to slide and rearrange under stress. These characteristics enable the hydrogel to conform to complex body contours and accommodate natural movements, reducing mechanical mismatch. Flexibility and stretchability are crucial for maintaining accurate signal acquisition and user comfort. Noteworthy is that excessive swelling could compromise mechanical strength. Therefore, optimizing hydrogel crosslinking density is critical for achieving optimal flexibility and stretchability in wearable applications. Materials explored for flexible and stretchable hydrogels include glycerol, polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), polyethylene glycol (PEG), polyacrylamide (PAAm), poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) (PNIPAm) and ionic salts [

101,

102,

107].

Wet adhesion: This refers to a material’s ability to adhere to moist or wet surfaces, such as human skin. Unlike traditional adhesives, hydrogels can adhere to moist or sweaty skin through hydrogen bonding, van der Waals interactions, and sometimes, covalent bonding with skin proteins. This wet adhesion is essential for maintaining stable contact during physical activity or prolonged wear, particularly in epidermal sensors and patches. It is essential that the hydrogel’s wet adhesion balances strength and removability to avoid skin damage or discomfort. Materials explored for wet adhesive hydrogels include adhesive moieties such as catechol groups, tannic acid, dopamine, gelatin, chitosan and hyaluronic acid [

107,

108,

109,

110].

Biocompatibility and skin conformability: Biocompatibility refers to the “ability of a material to perform with an appropriate host response in a specific application” [

111] without eliciting adverse effects such as toxicity, irritation, or immune response [

6]. Hydrogels naturally fulfill this requirement due to their high water content, soft and rubbery tissue-like consistency and hydrophilic surface, which collectively reduce interfacial energy and mechanical mismatch with skin. These properties minimize irritation and inflammation, making hydrogels ideal for continuous skin contact and even implantable devices. In parallel, their softness and conformability—attributable to low crosslinking density and high hydration—allow hydrogels to mould intimately to the skin’s microtopography, ensuring stable contact and user comfort. For wearable applications, it is essential that hydrogels maintain structural integrity while remaining non-toxic, non-immunogenic and free from leachable harmful substances. To further enhance these properties, bio-based materials, such as silk fibroin, gelatin, cellulose, chitosan, and alginate, have been explored for biocompatibility, offering additional benefits in terms of sustainability and biodegradability [

3,

102]. Some non-toxic, FDA-approved synthetic polymers include polyethylene glycol and polyvinyl alcohol. Softness and skin conformability have been improved using low-crosslinked polymers such as PAAm, poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate (PEGDA) and plasticizers like glycerol and sorbitol.

Permeability: This refers to a material’s ability to allow the passage of gases, water vapour, or small molecules through its structure. In hydrogels, this property arises from their porous polymer network, hydrophilic nature, and, in some cases, the presence of labile bonds that facilitate molecular diffusion. At high swelling levels, certain labile bonds may begin to dissociate, leading to partial degradation or dissolution of the hydrogel matrix. The degree of resistance to dissolution is primarily governed by the density and stability of crosslinks within the polymer network. Permeability is a critical parameter for wearable applications, particularly those involving skin contact, biochemical sensing, or controlled release. For instance, breathable hydrogels support skin respiration and enable the diffusion of sweat and analytes, which is essential for applications such as sweat-based diagnostics. In contrast, impermeable materials can trap moisture and heat, leading to discomfort, irritation, and reduced sensor performance due to sweat accumulation and skin occlusion. The interconnected microporous structure of hydrogels not only facilitates the efficient transport of heat and moisture but also contributes to their mechanical softness and deformability. This dual functionality makes hydrogels ideal for developing breathable, skin-conforming wearable devices and smart textiles. However, hydrogel permeability must be carefully balanced—excessive permeability can lead to dehydration and loss of structural integrity, while insufficient permeability may hinder comfort and sensor accuracy. Therefore, tailoring pore size, crosslinking density, and polymer composition is essential to optimize hydrogel performance for specific wearable applications. Materials explored for permeable hydrogels include alginate, gelatin, silicone, metal-coated nanofiber mesh coupled with PEDOT:PSS [

112], and PEG.

Optical transparency: This refers to the optical clarity of a material in the visible spectrum. This is achieved by avoiding phase separation and using optically clear polymers. Optically transparent hydrogels are advantageous for optical sensing and imaging applications. Transparency also allows for visual inspection of the skin beneath the wearable device, especially essential for clinical monitoring. Transparent hydrogels can be designed by optimizing hydrogel composition to enhance crystallinity and uniformity. Transparency should not compromise mechanical or functional performance. PEG, PVA and PAAm are among the optically clear polymers explored [

113,

114].

Electrical conductivity: This refers to the ability to conduct electrical current. Hydrogel conductivity is achieved by incorporating conductive fillers, metallic nanowires (e.g., silver nanowires), Mxenes, or using intrinsically conductive polymers, including PEDOT:PSS, polyaniline (PANI), and polypyrrole (PPy) [

115,

116,

117,

118,

119]. Conductive hydrogels enable the development of bioelectrodes and sensors that can transmit physiological signals with high fidelity. It is essential to maintain conductivity under deformation and over time; uniform dispersion of conductive elements is critical.

Self-healing: This refers to the ability of a material to autonomously repair mechanical damage. Self-healing hydrogels can autonomously repair mechanical damage through reversible physical interactions or chemical bonds such as hydrogen bonding, ionic interactions or dynamic covalent bonds (e.g., Schiff base and disulfide bonds). This property enhances device durability and longevity, especially in dynamic environments where mechanical stress is frequent. The healing speed and efficiency of hydrogels depend on environmental factors, such as temperature and humidity. Self-healing hydrogels have been developed using materials such as aldehyde-modified hyaluronic acid (AHA), aminated diselenide crosslinker 2,2′-diselanediyldiethanamine dihydrochloride (Sel) with diselenide bonds, aliphatic polycarbonate, sodium alginate/polyacrylamide, carboxymethyl chitosan/acryloyl-6-aminocaproic acid, carboxymethyl chitosan/poly(acrylic acid), and PEG functionalized with boronic acid [

120,

121].

This self-repairing capacity greatly enhances device durability and longevity, particularly in dynamic environments where wearable devices and textiles are subjected to frequent mechanical stress, such as bending, stretching, or impact. The healing speed and efficiency of these hydrogels depend on factors like temperature and humidity, with optimized matrices showing rapid recovery of both structure and electrical function after damage. For real-time monitoring applications, the restoration of conductivity and sensor integrity is essential [

122,

123]: when cracks or tears occur in the hydrogel electrode or sensor layer, dynamic interactions or reversible bonds reconnect the polymer network, restoring reliable measurement of biosignals or analyte concentrations without the need for manual intervention. Beyond mechanical resilience, self-healing hydrogel wearables provide protective benefits. Water-rich, elastic interfaces shield the skin while preserving breathability, minimizing irritation during continuous use. When combined with antimicrobial or UV-protective additives, self-healing hydrogels further safeguard users against environmental hazards and infection. Incorporating conductive fillers like carbon nanotubes or PEDOT:PSS allows both physical and electrical self-repair, vital for uninterrupted performance in health diagnostics, movement tracking, and smart textile systems. Examples of hydrogel-based wearables integrating self-healing properties are discussed in

Section 4 [

124,

125,

126].

Tunable mechanical properties: This refers to the ability of a material’s mechanical properties to be tuned. Hydrogels can be designed to have adjustable stiffness, toughness and elasticity by modifying their polymer composition, crosslinking density and incorporating reinforcing agents. This tunability allows customization for specific application requirements. Trade-offs between hydrogel mechanical strength and flexibility should be optimized. Materials explored include crosslinking agents like N, N’-methylenebisacrylamide (BIS), genipin, UV or ionic crosslinking and reinforcing materials like nanoclay, PAM, carboxymethyl chitosan [

127], cellulose nanocrystals, and microfibrillated cellulose [

128,

129].

Stimuli response: This is a material’s ability to change properties in response to external stimuli. Hydrogels can respond to temperature, pH, light, electric fields and other external stimuli. Their stimulus response is attributable to the presence or incorporation of functional groups or responsive moieties that undergo conformational or chemical changes in their microstructure. These responsive behaviours enable dynamic sensing, controlled release of functional agents and adaptive interfaces in wearable systems. For wearable devices and textiles, hydrogel responsiveness should be reversible, repeatable and compatible with physiological conditions. Thermoresponsive polymers (e.g., PNIPAm, hydroxypropyl cellulose), pH-responsive polymers (e.g., polyacrylic acid and chitosan), light-responsive polymers (e.g., azobenzene), and electric field-responsive materials (e.g., polyelectrolytes) have been explored for stimuli-responsive hydrogels [

130,

131].

3.3. Hydrogel Types Applicable for Wearables

3.3.1. Conductive Hydrogels

Conductive hydrogels, unlike conventional hydrogels, possess intrinsic electrical conductivity. Their electrical properties are primarily governed by the nature of their polymeric constituents and the type of conductive materials incorporated. Based on their conductive components, conductive hydrogels have been classified into three categories: (1) ionic conductive hydrogels, which incorporate ionic liquids and electrolytes; (2) nanocomposite conductive hydrogels, which include ionized nanotubes or inorganic conductive fillers; and (3) polymeric conductive hydrogels, which are based on intrinsically conductive polymers [

132].

These hydrogels exhibit high electrical conductivity, as well as tunable physicochemical properties and responsiveness to external stimuli [

133,

134,

135,

136], making them highly promising for smart wearable devices and textiles. Potential uses include smart sensors, energy storage and conversion, health monitoring and human–computer interfaces [

137].

Ionic Versus Electronic Conductivity Mechanisms

The electrical conductivity of conductive hydrogels arises from two primary mechanisms—ionic conduction and electronic conduction [

132,

138]. These mechanisms differ fundamentally in their charge-carrier types, transport pathways, and material compositions, making them suitable for different wearable applications. Understanding these mechanisms is essential for selecting appropriate hydrogels for specific wearable applications.

Ionic conduction involves the migration of cations and anions through the three-dimensional hydrogel network via electrostatic interactions and hydration effects. In these hydrogels, ions move through interconnected aqueous pathways created by polymer chains and their interstitial spaces, mimicking biological ion transport mechanisms. This approach is particularly valuable for bioelectronic applications such as bioelectrodes and biosensors, where intimate contact with biological tissues is required. Ionic hydrogels demonstrate excellent ionic conductivity (up to 51.48 S/cm), water retention, mechanical elasticity, optical transparency, and anti-freezing capabilities [

139,

140].

Electronic conduction is achieved by embedding conductive electronic components within the polymer matrix to form continuous electron transport pathways. This mechanism depends on the transport of electrons or holes through the material via π-electron delocalization in conjugated polymer backbones. Electrons move efficiently through hopping or tunnelling mechanisms, enhanced by the formation of percolation pathways—continuous networks of interconnected conductive components that facilitate electron mobility. Conjugated polymers such as polyaniline (PANI), polypyrrole (PPy), and poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) (PEDOT) achieve high conductivity (10–1000 S/cm for PEDOT:PSS) through this mechanism. Electronic conduction enables faster signal transmission and higher overall conductivity, making it advantageous for applications requiring rapid electronic response times [

132,

141].

Thus, ionic hydrogels preserve inherent soft material properties and excel at biocompatibility, while electronic conduction may enhance mechanical robustness through integration of rigid conductive fillers. Advanced hydrogels employ dual-conductive mechanisms, combining both ionic and electronic pathways to optimize performance for hybrid applications—for example, achieving both lithium-ion conductivity (0.000276 S/cm) and electronic conductivity (68.9 S/cm) [

142]. Carbon-based materials with sp

2-hybridized carbon atoms (graphene, carbon nanotubes) enable particularly efficient electron transport; single-walled carbon nanotubes can achieve conductivity of 100 to 1,000,000 S/cm, while graphite with perpendicular atomic arrangements exhibits lower conductivity [

132].

Classification of Conductive Hydrogels

Based on their conductive mechanisms and materials, conductive hydrogels are classified as ionic conductive hydrogels, electroconductive hydrogels, and metal-based conductive hydrogels [

132,

143,

144].

Ionic conductive hydrogels feature repeating cationic and anionic groups within a 3D network with interconnected pores enabling ion transport. The conductivity mechanism arises from molecular-scale ion channels formed by specific ion coordination—for example, coordination between alginate G-block units and lithium ions facilitates directional ion migration under electric fields. Hydration and swelling behaviours further modulate conductivity by enlarging free volume for ion movement. These hydrogels demonstrate excellent ionic conductivity, water retention, mechanical elasticity, optical transparency and anti-freezing capabilities [

133,

134].

Electroconductive hydrogels integrate electroconductive materials (polypyrrole, polyaniline, carbon nanotubes) with polymeric matrices such as polyvinyl alcohol [

145,

146]. Their conductivity derives from delocalized π-electron systems within conjugated polymer backbones, enabling efficient electron transport.

Metal-based conductive hydrogels utilize the superior electrical and mechanical properties of metals (gold, silver, platinum, palladium) to enhance overall performance [

132]. These metal nanoparticles are incorporated through crosslinkers, precursors, or direct integration, forming conductive networks that enhance electron transport with conductivity values ranging from 0.3 to 0.8 S/cm (gold) to 0.5–0.7 S/cm (silver).

Self-Healing Conductive Hydrogels

Despite their advantages, conductive hydrogels face challenges, including limited operating temperature ranges, suboptimal mechanical strength, and difficulty restoring conductivity and mechanical integrity after damage [

147,

148]. Self-healing conductive hydrogels address these limitations by restoring both electrical and mechanical functionality.

Self-healing mechanisms (briefly introduced in

Section 3.2) operate through non-covalent interactions, including hydrogen bonding, van der Waals forces, and π-π stacking, enabling rapid recovery at room temperature without external stimuli [

149]. Mechanically and electrically self-healing hydrogels incorporating multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) can recover mechanical properties and electromagnetic interference (EMI) shielding effectiveness within 7 days, with self-healing efficiency reaching 77.2% [

150]. The synergistic effect of recombination of hydrophobic interactions and the readsorption of polymer chains onto MWCNT and cellulose nanofiber surfaces enables simultaneous recovery of mechanical damage and electrical conductivity. Advanced formulations achieve 80–95% recovery of mechanical properties within minutes to hours through cooperative dynamic interactions [

149].

These self-healing conductive hydrogels restore interior structure, mechanical properties, electrical conductivity, and EMI shielding performance after mechanical damage, enhancing the durability, cost-effectiveness, and environmental sustainability of wearable devices. The ability to simultaneously restore electrical and mechanical functionality is particularly valuable for long-term wearable applications where device integrity is critical to continuous performance. Composite hydrogels with enhanced stretchability, compressibility, adhesion, anti-freezing properties, water retention, and antibacterial activity represent the current frontier in conductive hydrogel development.

3.3.2. Natural Polymer-Based Hydrogels

Natural polymer-based hydrogels play a transformative role in advancing wearable technology, particularly due to their biocompatibility, flexibility, and responsiveness to stimuli. Natural polymer-based hydrogels are increasingly investigated in wearable devices for flexible sensors, drug delivery systems, wound monitoring, sweat and motion detection and bioelectronic interfaces. There is also a desire to develop environmentally sustainable wearables, which has led to the exploration of natural polymers such as those based on cellulose [

151,

152,

153] and chitin [

154] and their derivatives [

155,

156], due to their natural abundance and non-toxicity. The strategic importance of natural polymers extends beyond simple availability; they offer clear biocompatibility advantages, biodegradability, and low environmental impact, addressing the growing demand for sustainable wearable devices and textiles.

Cellulose-Based Hydrogels

Cellulose is the most abundant natural polymer on earth, providing a low-cost and sustainable resource that is renewable, degradable and biocompatible. Cellulose consists of linear chains of repeating β-D-glucopyranose units covalently linked through β-1,4 glycosidic bonds, with a large number of hydrogen bonds existing intra- and inter-molecularly to produce different configurations of cellulose structure [

4,

157]. The structural and chemical features of cellulose, including transparency, low thermal expansion, anisotropy, high elasticity, and flexible surface chemistry, have enabled the functionalization and engineering of cellulose-based hydrogels for wearable technology [

151,

152,

153,

158], as discussed in

Section 4. During cellulose dissolution, intramolecular hydrogen bonds are broken, and the supramolecular structure is disrupted, enhancing the activity of hydroxyl groups and enabling easier combination with other natural or synthetic polymers by reconstructing hydrogen bonds. Cellulose-based hydrogels endow specific performance, such as biodegradability, renewability, flexibility, and high mechanical strength. Cellulose-based hydrogels have also been explored for their adaptability to mechanical and anti-freezing properties, even at sub-zero temperatures [

159].

Polysaccharide-Based Hydrogels

Other natural polymers commonly explored for wearables include polysaccharides [

160,

161,

162,

163,

164,

165,

166] such as chitosan, alginate and starch, as well as less-explored glycosaminoglycans [

167] such as hyaluronic acid and chondroitin sulfate.

Chitosan has been explored for its antimicrobial properties and biodegradability in biosensing applications. As the only cationic polysaccharide found among natural polysaccharides, chitosan is well known for its antimicrobial and antifungal properties, enabling interactions with negatively charged surfaces of cells and microbes. Chitosan exhibits degradability in vivo by human proteases such as lysozyme due to its multiple amino groups. Recent studies have highlighted the antitumor activity, mucoadhesive, and hemostatic properties of chitosan. However, the applications of chitosan-based hydrogels in wearable technology have been limited by insufficient mechanical strength and inadequate degradation rates, necessitating the preparation of composites by mixing chitosan with other functional substances to improve performance.

Alginate has been studied in flexible sensors and delivery systems. Alginate is a naturally available biopolymer and a linear anionic polysaccharide consisting of repeated residues of α-L-glucuronate (G) and β-D mannuronate (M) [

168]. It provides biocompatibility, biodegradability, non-antigenicity, chelating ability, and good stability for extended periods. The mechanical properties of alginate hydrogels formed through ionic crosslinking with divalent cations (e.g., Ca

2+, Ba

2+, Zn

2+) are directly related to the concentration of the crosslinking cation and the molecular weight and composition of G-blocks. Although alginate is biocompatible, biodegradable, and non-toxic, it has several disadvantages, such as low bioadhesivity and biological inertness, which limit its applications in smart wearables. The partial oxidation of alginate chains is an attractive method to make alginate degradable under physiological conditions by altering the chain conformation to enable backbone degradation.

Starch is abundant and biodegradable and is being explored for eco-friendly wearable substrates. Starch is a natural polysaccharide composed of glucose repeating units linked through α-D-(1-4) and α-D-(1-6) glycosidic linkages, with a wide range of applications due to its low cost, renewability, biodegradability, and biocompatibility [

159]. Rich in hydroxyl groups, starch has excellent hydrophilic properties and is an ideal candidate for developing hydrogels with higher swelling capacity and enhanced biodegradability. Modified starch, such as ozonated cassava starch, can be processed into hydrogels with improved properties, including better pasting properties and printability.

Hyaluronic acid (HA), with its excellent moisture retention and biocompatibility, has been explored for skin-contact applications. As a main component of the extracellular matrix found prominently throughout the body, hyaluronic acid comprises N-acetyl-glucosamine and D-glucuronic acid residues [

169]. It is well known for its bioactivity and plays significant roles in lubrication, water absorption and retention, and structural functions, while interacting with various cell receptors to coordinate cell communication and behaviour. Because of its nontoxicity, non-allergenicity, biocompatibility, and biodegradability, hyaluronic acid has been widely used as a biomedical material. Hyaluronic acid degrades rapidly in the body and is often used in combination with other materials to extend retention time in vivo. The chemical modification of hyaluronic acid focuses on distinct functional groups, including glucuronic carboxylic acids, primary and secondary hydroxyl groups, and N-acetyl groups.

Limitations of Natural Polymer-Based Hydrogels

Natural polymer-based hydrogels show limitations in mechanical strength and degradation control. To overcome these limitations, they are often subjected to chemical modifications, crosslinking, or blending with other natural polymers or synthetic polymers to form composite hydrogels. For example, alginate dialdehyde–gelatin hydrogels show higher degradability compared to alginate alone and exhibit good cell adhesion, proliferation, and migration properties. Although natural polymers can increase the degradation rate of hydrogels in general, the reaction employed can control the degradation rate of the material. The presence of ester groups allows ease of degradation, whereas biomolecules with aldehyde and carboxylic acid functional groups show decreased degradation [

170]. Degradation depends not solely on certain functional groups but on the interactions between biomolecules—strong conjugation leads to slow or limited degradation, while weak conjugation or free polymeric chains can disrupt hydrogen bonding, rendering chains more mobile and decreasing water-holding capacity.

3.3.3. Composite Hydrogels

Composite hydrogels represent a sophisticated design strategy to overcome the inherent limitations of single-component hydrogels by combining multiple materials to achieve synergistic improvements in electrical conductivity, mechanical properties, flexibility, adhesion, self-healing, and biocompatibility. The fundamental approach involves incorporating nanoparticles, conducting polymers, carbon-based materials, metal nanoparticles, and reinforcing fibers into hydrogel matrices, creating multifunctional materials particularly suitable for biosensors, bioelectronics, flexible sensors, and wearable device applications. This approach explores the synergistic effects of different components.

Component Integration and Design Strategy

Composite hydrogels strategically combine diverse primary components (conducting polymers, carbon-based materials and metal nanoparticles) to exploit the strengths of each material [

171]. Conducting polymers such as polyaniline and poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) (PEDOT) enhance electronic conductivity through delocalized π-electron systems while maintaining flexibility, softness, and biocompatibility essential for user comfort. Carbon-based materials, including graphene oxide and carbon nanotubes, improve both electrical conductivity and mechanical strength through percolation network formation. Metal nanoparticles (gold, silver, platinum, palladium) further enhance electrical conductivity and impart antibacterial properties. Reinforcing nanofibers such as cellulose nanofibers (CNF) create mechanical reinforcement networks through hydrogen bonding and physical entanglement with the polymer matrix.

The key innovation involves in situ polymerization of conducting monomers within the hydrogel matrix, ensuring uniform distribution of conductive materials while enabling fine-tuning of hydrogel properties through adjustable polymerization conditions. This approach produces meta-composites with robust, durable properties that integrate the strengths of each component—electronic conductivity from conjugated polymers, mechanical stability from nanofibers and reinforcing materials, and biological functionality from natural polymers and metal nanoparticles.

Natural and Natural Polymer (Biopolymer-Based) Composites

Natural polymers are combined to enhance properties and achieve multifunctionality while maintaining the environmental sustainability of the hydrogels. Recent advances have demonstrated multiresponsive natural polymer composite hydrogels that respond to multiple environmental stimuli, including temperature, humidity, strain, and light, offering high transparency and biocompatibility for real-time biosensing and wearable e-skin applications. For example, alginate–gelatin hydrogels achieve multiresponsiveness through ionic crosslinking with multivalent cations, enabling responsive behaviour across diverse environmental parameters [

172]. The combination of sodium alginate and gelatin provides an excellent hydrogel substrate due to its unique biological properties, including biocompatibility, biodegradability, and non-toxicity. The obtained alginate–gelatin crosslinked hydrogel (ADA-GEL, formed through covalent crosslinking of alginate dialdehyde and gelatin via Schiff base formation) can be used to produce hydrogels with good mechanical strength and biocompatibility for regenerative medicine applications [

173]. Cellulose derivatives and chitosan have also been explored for the development of thermoresponsive hydrogels with excellent hydrolytic stability [

6]. Chitosan–alginate bilayer hydrogels exemplify synergistic electrostatic interactions. Chitosan, derived from chitin through deacetylation, becomes positively charged in acidic environments (pH < 6.5) due to its protonated amino groups. Alginate, a polysaccharide from brown seaweed featuring a negatively charged backbone (carboxyl functional groups), remains water-soluble and forms gels through ionic crosslinking with divalent cations such as Ca

2+. The electrostatic attraction between positively charged chitosan and negatively charged alginate significantly enhances hydrogel adhesion to biological tissues and skin, creating bilayer structures with improved overall performance. This combination allows independent tuning of individual layer properties while maintaining integrated functionality.

Natural and Synthetic Polymer Composites

Natural polymers are also combined with synthetic polymers—including cellulose derivatives, gelatin, chitosan, hyaluronic acid, and alginate—selected for their inherent biocompatibility and bioactivity. Synthetic polymers—such as polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) and polyethylene glycol (PEG)—provide tunable mechanical properties and controllable degradation rates. The combination of these components creates hydrogels with precisely engineered functionality. For example, alginate–PVA composites leverage alginate’s biocompatibility and stimuli-responsiveness combined with PVA’s mechanical strength and thermal stability, creating flexible yet robust materials suitable for long-term wearable applications. Bilayer hydrogels with Janus characteristics have also been developed, combining gelatin and modified polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) through dynamic interfacial bonding via Schiff-base bonds and hydrogen bonding at ambient conditions [

172]. These bilayer hydrogels exhibited high stretchability, flexibility, and toughness, with the PVA-rich layer contributing to mechanical strength and water retention while the gelatin-based layer provided softness and biocompatibility. Mechanical properties can be fine-tuned by adjusting polymer concentration, crosslinking time, and functional group density. Anisotropic swelling—where one layer swells more than the other upon water absorption—enabled directional actuation and programmable, stimuli-responsive behaviour with controlled shape transformation.

Recent advances demonstrate that composite hydrogel design can achieve exceptional mechanical properties through multi-network architectures [

171,

174]. A notable example is the triple-network interlocked structure developed by combining PVA/polyacrylamide (PAM) dual-network hydrogels with cellulose nanofibers (CNF) [

171]. The CNFs form numerous hydrogen bonds and entanglements with the polymer matrix, with their hydroxyl groups interacting with the PVA network to create a third conductive network. This triple-interlocking integration creates multiple energy-dissipation pathways, resulting in composite hydrogels with mechanical strengths of 1.41 MPa and toughness of 6.73 MJ/m

3 after a single freeze–thaw cycle. Coordination between Zn

2+ ions and carboxyl groups on CNF further reinforces network interlocking, imparting exceptional electrical conductivity, antibacterial properties, high transparency (89.8%), sensitivity, and biocompatibility—making such materials promising for biosensing and flexible electronics. Double-network hydrogels consisting of a stiff first network interpenetrated with a flexible second network overcome the mechanical limitations of single-network materials. The stiff first network fractures under stress, dissipating mechanical energy and preventing catastrophic failure, while the flexible second network maintains structural integrity. This architecture enables simultaneous high strength (tensile strength >1 MPa) and high stretchability (elongation at break >400%), properties rarely achieved in conventional materials.

Elastomer-Conductive Filler Composites

Elastomers and self-healing polymers—including styrene–ethylene–butylene–styrene (SEBS), polyurethane, and polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS)—can be combined with conductive fillers such as graphene, carbon nanotubes, silver nanoparticles, and liquid metal to form hydrogel composites with enhanced stretchability, conductivity, and biocompatibility [

175]. Liquid metal, commonly used for its superior thermal and electrical conductivity (approximately 10

6 S/m) and excellent mechanical properties, creates percolating conductive pathways within elastomeric matrices [

176]. The inherent flexibility of elastomeric backbones, combined with the high conductivity of liquid metal, enables wearable devices that stretch to over 400% strain while maintaining electrical functionality, critical for applications requiring conformability to curved body surfaces and dynamic motion.

Thus, composite hydrogels demonstrate superior performance compared to pure natural polymer hydrogels by maintaining aqueous biocompatibility while incorporating mechanical robustness and electrical functionality. Cellulose nanofibers can create reinforcing networks, enhancing tensile strength and elastic modulus without compromising inherent flexibility. Graphene oxide integration can improve both mechanical properties and electrical conductivity by forming a percolation network, enabling multifunctional sensing capabilities. These composites achieve stretchability exceeding 400% strain while maintaining electrical conductivity in the range of 0.01–0.1 S/m [