One-Pot Synthesis of Mechanically Robust Eutectogels via Carboxyl-Al(III) Coordination for Reliable Flexible Strain Sensor

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

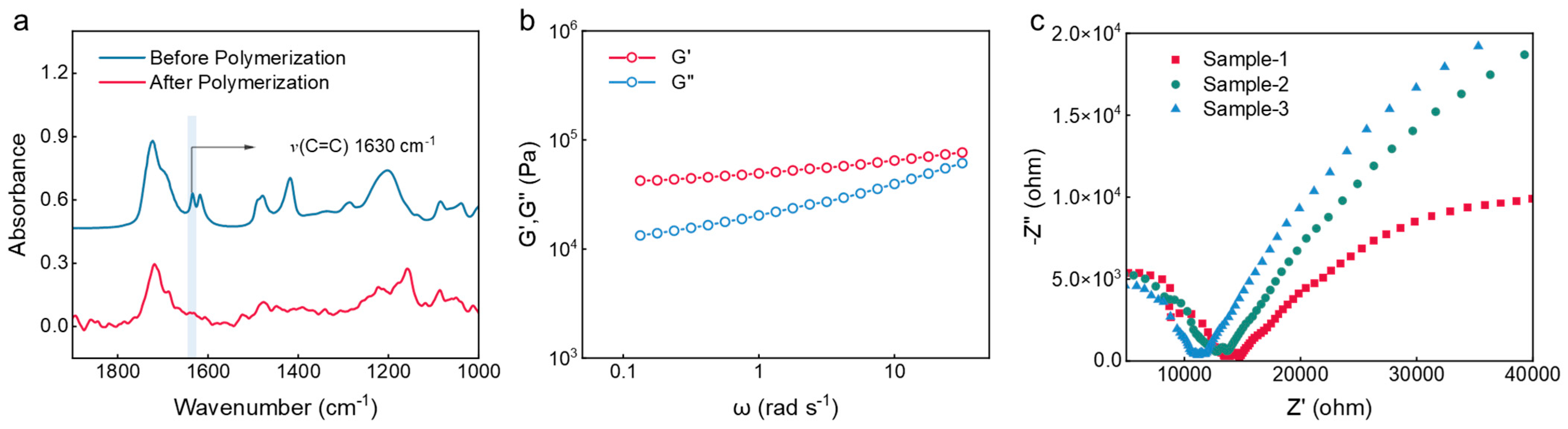

2.1. Design and Preparation of Eutectogel

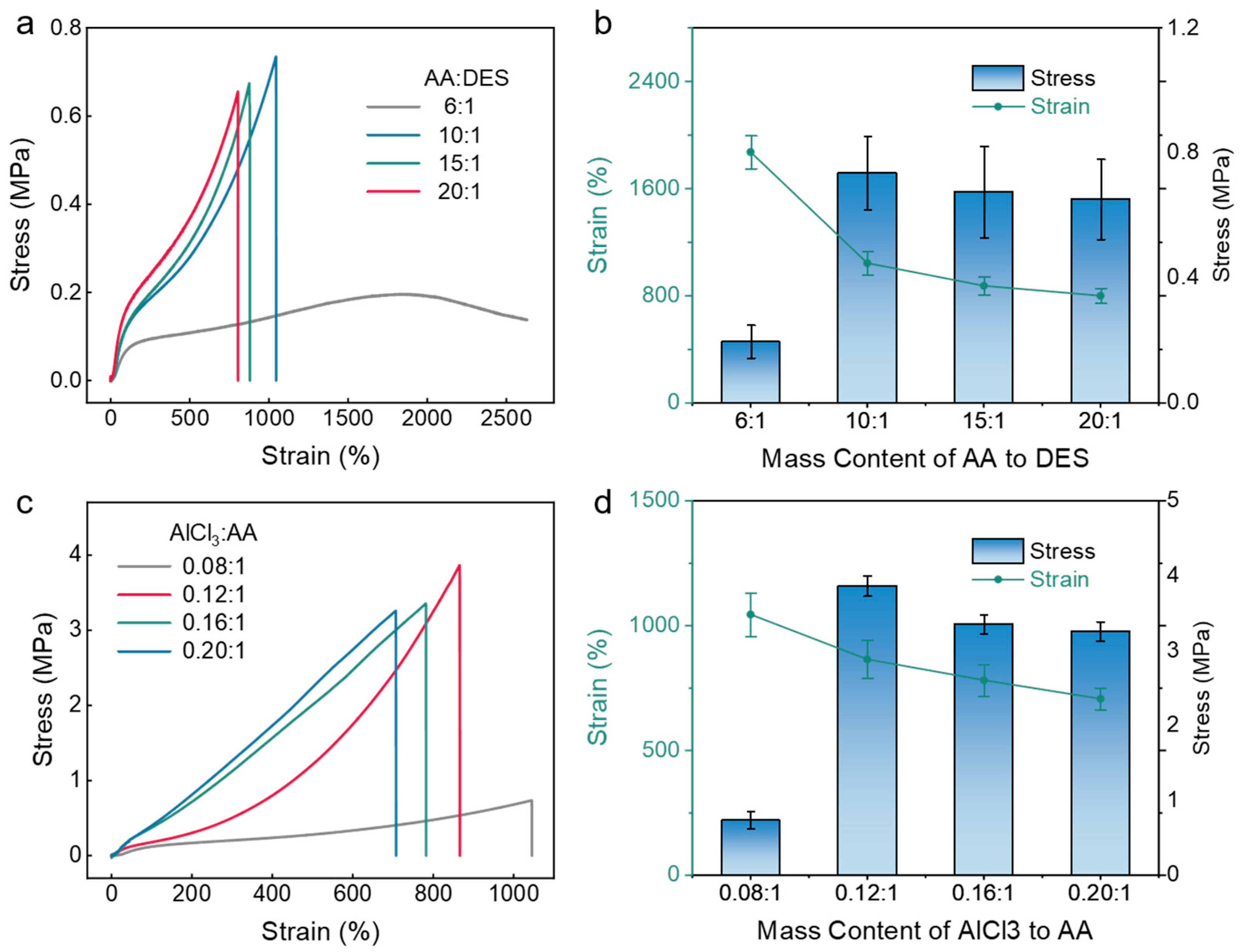

2.2. Mechanical Performance of Eutectogel

2.3. Cyclic Tensile Performance Testing

2.4. Environmental Stability of Eutectogel

2.5. Sensing Performance Testing

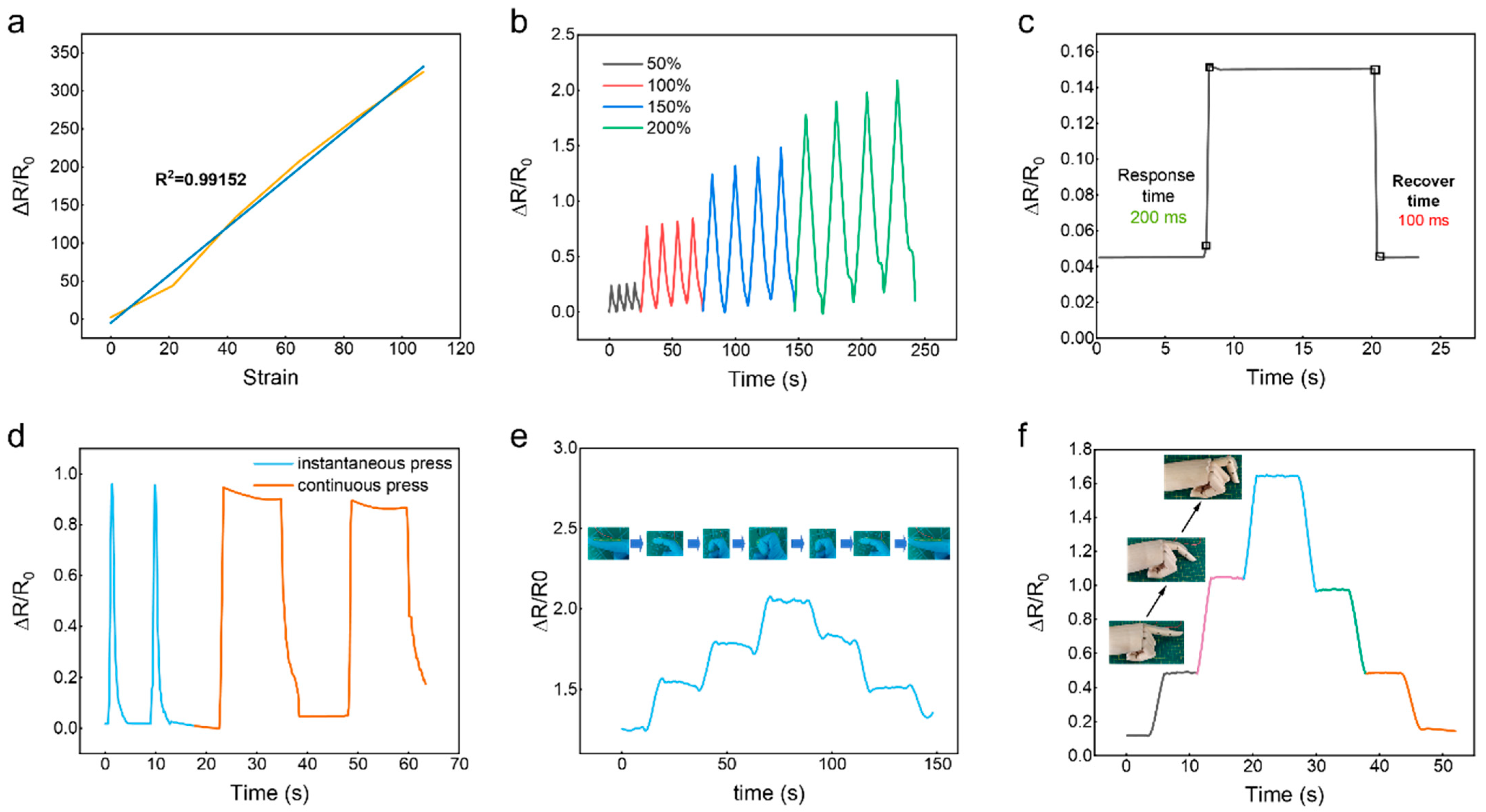

2.5.1. Mechanical–Electric Sensing Performance of the Flexible Strain Sensor

2.5.2. Real-Time Sensing Performance of the Flexible Strain Sensor

2.5.3. Data Transmission of Eutectogel-Based Flexible Strain Sensor via Morse Code

3. Conclusions

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Instruments

4.2. Chemicals

4.3. Synthesis of DES Solution

4.4. Preparation of Eutectogel

4.5. Mechanical Test of Eutectogel

4.6. Preparation of Constructing Strain Sensor

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dong, M.; Han, Y.; Hao, X.P.; Yu, H.C.; Yin, J.; Du, M.; Zheng, Q.; Wu, Z.L. Digital Light Processing 3D Printing of Tough Supramolecular Hydrogels with Sophisticated Architectures as Impact-Absorption Elements. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34, 2204333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Xu, Z.; Lovrak, M.; le Sage, V.A.A.; Zhang, K.; Guo, X.; Eelkema, R.; Mendes, E.; van Esch, J.H. Biomimetic Strain-Stiffening Self-Assembled Hydrogels. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 4830–4834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Qin, J.; Li, W.; Tyagi, A.; Liu, Z.; Hossain, M.D.; Chen, H.; Kim, J.-K.; Liu, H.; Zhuang, M.; et al. A stretchable, conformable, and biocompatible graphene strain sensor based on a structured hydrogel for clinical application. J. Mater. Chem. A 2019, 7, 27099–27109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Z.; Fu, Q.-Q.; Wang, M.-H.; Gao, H.-L.; Dong, L.; Zhou, P.; Cheng, D.-D.; Chen, Y.; Zou, D.-H.; He, J.-C.; et al. Designing nanohesives for rapid, universal, and robust hydrogel adhesion. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 5378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Deng, Z.; Liu, X.; Huang, T.; Hu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Y.; Guo, Z.-H.; Yue, K. Highly stretchable, strain-stiffening, self-healing ionic conductors for wearable sensors. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 449, 137633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.H.; Suo, Z.G. Hydrogel ionotronics. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2018, 3, 125–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, G.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, Y.Z.; Alshareef, H.N.; Dong, X.C. 3D Printing of Hydrogels for Stretchable Ionotronic Devices. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31, 2107437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.H.; Dong, T.; Chen, Y.H.; Sun, N.; Liu, Q.; Huang, Z.K.; Yang, Y.F.; Cheng, H.; Yue, K. Biodegradable and Cytocompatible Hydrogel Coating with Antibacterial Activity for the Prevention of Implant-Associated Infection. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 11507–11519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, L.G.; Huang, Z.K.; Deng, Z.S.; Du, Z.K.; Sun, T.L.; Guo, Z.H.; Yue, K. A Transparent, Highly Stretchable, Solvent-Resistant, Recyclable Multifunctional Ionogel with Underwater Self-Healing and Adhesion for Reliable Strain Sensors. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, 2105306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tie, J.F.; Mao, Z.P.; Zhang, L.P.; Zhong, Y.; Xu, H. Strong and Ultratough Ionogel Enabled by Ingenious Combined Ionic Liquids Induced Microphase Separation. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 33, 2307367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, C.; Chen, Y.; Huang, Z.; Fu, M.; Ou, W.; Huang, T.; Yue, K. A Fully Self-Healing and Highly Stretchable Liquid-Free Ionic Conductive Elastomer for Soft Ionotronics. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 33, 2304486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Peng, J.; Huang, T.; Hu, F.; Liu, X.; Xu, L.; Yue, K. Highly stretchable ionotronic pressure sensors with broad response range enabled by microstructured ionogel electrodes. J. Mater. Chem. A 2023, 11, 7201–7212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, F.; Huang, Z.; Luo, C.; Yue, K. High-sensitivity and ultralow-hysteresis fluorine-rich ionogel strain sensors for multi-environment contact and contactless sensing. Mater. Horiz. 2023, 10, 5907–5919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.K.; Xu, L.G.; Liu, P.J.; Peng, J.P. Transparent, mechanically robust, conductive, self-healable, and recyclable ionogels for flexible strain sensors and electroluminescent devices. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 28234–28243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.T.; Huang, Z.K.; Hu, F.Q.; Peng, J.P.; Huang, T.R.; Liu, X.; Luo, C.; Xu, L.G.; Yue, K. Microstructured Polyfluoroacrylate Elastomeric Dielectric Layer for Highly Stretchable Wide-Range Capacitive Pressure Sensors. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 58700–58710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, C.C.; Li, W.Z.; Liu, Z.Y.; Zheng, S.J.; Hu, Y.; Zhou, Y.J.; Guo, J.N.; Ou, X.; Li, Q.N.; Yu, J.T.; et al. Ionogels: Preparation, Properties and Applications. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2314408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.T.; Liu, S.Q.; Jia, Z.H.; Koh, J.J.; Yeo, J.C.C.; Wang, C.G.; Surat’man, N.E.; Loh, X.J.; Le Bideau, J.; He, C.B.; et al. Ionogels: Recent advances in design, material properties and emerging biomedical applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2023, 52, 2497–2527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen, B.B.; Spittle, S.; Chen, B.; Poe, D.; Zhang, Y.; Klein, J.M.; Horton, A.; Adhikari, L.; Zelovich, T.; Doherty, B.W.; et al. Deep Eutectic Solvents: A Review of Fundamentals and Applications. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 1232–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Achkar, T.; Greige-Gerges, H.; Fourmentin, S. Basics and properties of deep eutectic solvents: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2021, 19, 3397–3408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, K.; Peng, J.; Yang, W.; Wang, X.; Liu, S.; Cao, L.; Sun, H.; Zhang, X. One-step preparation of highly conductive eutectogel for a flexible strain sensor. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2024, 141, e55561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, C.J.; Tu, W.C.; Levers, O.; Bröhl, A.; Hallett, J.P. Green and Sustainable Solvents in Chemical Processes. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 747–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paiva, A.; Craveiro, R.; Aroso, I.; Martins, M.; Reis, R.L.; Duarte, A.R.C. Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents—Solvents for the 21st Century. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2014, 2, 1063–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, E.L.; Abbott, A.P.; Ryder, K.S. Deep Eutectic Solvents (DESs) and Their Applications. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 11060–11082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, M.; Thomas, M.L.; Zhang, S.G.; Ueno, K.; Yasuda, T.; Dokko, K. Application of Ionic Liquids to Energy Storage and Conversion Materials and Devices. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 7190–7239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.K.; Xie, J.H.; Li, T.G.; Xu, L.G.; Liu, P.J.; Peng, J.P. Highly Transparent, Mechanically Robust, and Conductive Eutectogel Based on Oligoethylene Glycol and Deep Eutectic Solvent for Reliable Human Motions Sensing. Polymers 2024, 16, 2761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.F.; Li, X.J.; Li, J.Y.; Wang, Q.Y.; Dong, X.M.; Wu, Y.Y.; Li, Z.F.; Xie, X.Y.; Liu, Z.D.; Xiu, F.; et al. Phase-Segregated Ductile Eutectogels with Ultrahigh Modulus and Toughness for Antidamaging Fabric Perception. Small 2024, 20, 2306557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Liu, J.; Qiu, X.; Yang, X.; Huang, X.; Zhang, X. Photoswitchable and Reversible Fluorescent Eutectogels for Conformal Information Encryption. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202313971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Guan, Y.; Zhang, Y. Peptide-enhanced tough, resilient and adhesive eutectogels for highly reliable strain/pressure sensing under extreme conditions. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 6671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Yu, J.; Sun, D.; Dang, C.; Ren, W.; Shao, C.; Sun, R. Extreme environment-adaptable and fast self-healable eutectogel triboelectric nanogenerator for energy harvesting and self-powered sensing. Nano Energy 2022, 98, 107284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, C.; Wang, M.; Zhang, K.; Li, J.; Lu, Y.-L.; Cui, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, C.-S. A Full-Device Autonomous Self-Healing Stretchable Soft Battery from Self-Bonded Eutectogels. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, 2208392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Liu, Z.; Hu, Y.; Li, R.; Cao, Y. A hydrophobic eutectogel with excellent underwater Self-adhesion, Self-healing, Transparency, Stretchability, ionic Conductivity, and fully recyclability. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 472, 145177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, D.; Zhou, J.; Kaneko, T.; Dong, W.; Chen, M.; Shi, D. Stretchable and hydrophobic eutectogel for underwater human health monitoring based on hierarchical dynamic interactions. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 474, 145704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Lu, N.; Jiang, D.; Zhang, H.; Wang, G. A highly adhesive and mechanically robust eutectogel electrolyte for constructing stable integrated stretchable supercapacitors. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 475, 146378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Deng, Y.; Zhang, K.; Qiu, J.; Wu, J.; Yan, L. Ultrahigh Conductive and Stretchable Eutectogel Electrolyte for High-Voltage Flexible Antifreeze Quasi-solid-state Zinc-Ion Hybrid Supercapacitor. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2022, 5, 3013–3021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panzer, M.J. Holding it together: Noncovalent cross-linking strategies for ionogels and eutectogels. Mater. Adv. 2022, 3, 7709–7725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Yang, L.; Wang, J.; Li, S.; Zhang, X.; Chen, D.; Ma, Y.; Yang, W. Degradable Supramolecular Eutectogel-Based Ionic Skin with Antibacterial, Adhesive, and Self-Healable Capabilities. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 36759–36770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Jia, L.; Yu, J.; Xu, H.; Guo, X.; Xiang, T.; Zhou, S. Environmentally tolerant multifunctional eutectogel for highly sensitive wearable sensors. Mater. Horiz. 2025, 12, 2604–2618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, K.; Wei, W.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, B.; Feng, W.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, X. Highly stretchable, self-healing, and adhesive polymeric eutectogel enabled by hydrogen-bond networks for wearable strain sensor. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 449, 137878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Tang, N.; Yu, X.; Li, M.-H.; Hu, J. Strong and Tough Physical Eutectogels Regulated by the Spatiotemporal Expression of Non-Covalent Interactions. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2206305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Liu, H.; Duan, L.; Gao, G. Tough hydrogel based on covalent crosslinking and ionic coordination from ferric iron and negative carboxylic groups. Eur. Polym. J. 2018, 106, 297–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.C.; Hao, X.P.; Zhang, C.W.; Zheng, S.Y.; Du, M.; Liang, S.; Wu, Z.L.; Zheng, Q. Engineering Tough Metallosupramolecular Hydrogel Films with Kirigami Structures for Compliant Soft Electronics. Small 2021, 17, 2103836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.X.; Zhang, P.Y.; Shamsi, M.; Thelen, J.L.; Qian, W.; Truong, V.K.; Ma, J.; Hu, J.; Dickey, M.D. Tough and stretchable ionogels by in situ phase separation. Nat. Mater. 2022, 21, 359–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.X.; Liu, E.J.; Hao, S.; Yang, X.M.; Li, T.C.; Lou, C.G.; Run, M.T.; Song, H.Z. 3D Printable, ultra-stretchable, Self-healable, and self-adhesive dual cross-linked nanocomposite ionogels as ultra-durable strain sensors for motion detection and wearable human-machine interface. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 431, 133949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, S.F.; He, X.J.; Zheng, F.; Lu, Q.H. Multifunctional flexible sensors based on ionogel composed entirely of ionic liquid with long alkyl chains for enhancing mechanical properties. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 439, 135644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, A.; Yan, F. Flexible Electrochemical Biosensors for Health Monitoring. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 2021, 3, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amirjani, A.; Kamani, P.; Hosseini, H.R.M.; Sadrnezhaad, S.K. SPR-based assay kit for rapid determination of Pb2+. Anal. Chim. Acta 2022, 1220, 340030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Huang, Z.; Song, Y.; Zhao, S.; Liu, P.; Peng, J. One-Pot Synthesis of Mechanically Robust Eutectogels via Carboxyl-Al(III) Coordination for Reliable Flexible Strain Sensor. Gels 2025, 11, 963. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11120963

Huang Z, Song Y, Zhao S, Liu P, Peng J. One-Pot Synthesis of Mechanically Robust Eutectogels via Carboxyl-Al(III) Coordination for Reliable Flexible Strain Sensor. Gels. 2025; 11(12):963. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11120963

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuang, Zhenkai, Yutao Song, Shanzheng Zhao, Peijiang Liu, and Jianping Peng. 2025. "One-Pot Synthesis of Mechanically Robust Eutectogels via Carboxyl-Al(III) Coordination for Reliable Flexible Strain Sensor" Gels 11, no. 12: 963. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11120963

APA StyleHuang, Z., Song, Y., Zhao, S., Liu, P., & Peng, J. (2025). One-Pot Synthesis of Mechanically Robust Eutectogels via Carboxyl-Al(III) Coordination for Reliable Flexible Strain Sensor. Gels, 11(12), 963. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11120963