A Novel Phenolic Resin Aerogel Modified by SiO2-ZrO2 for Efficient Thermal Protection and Insulation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

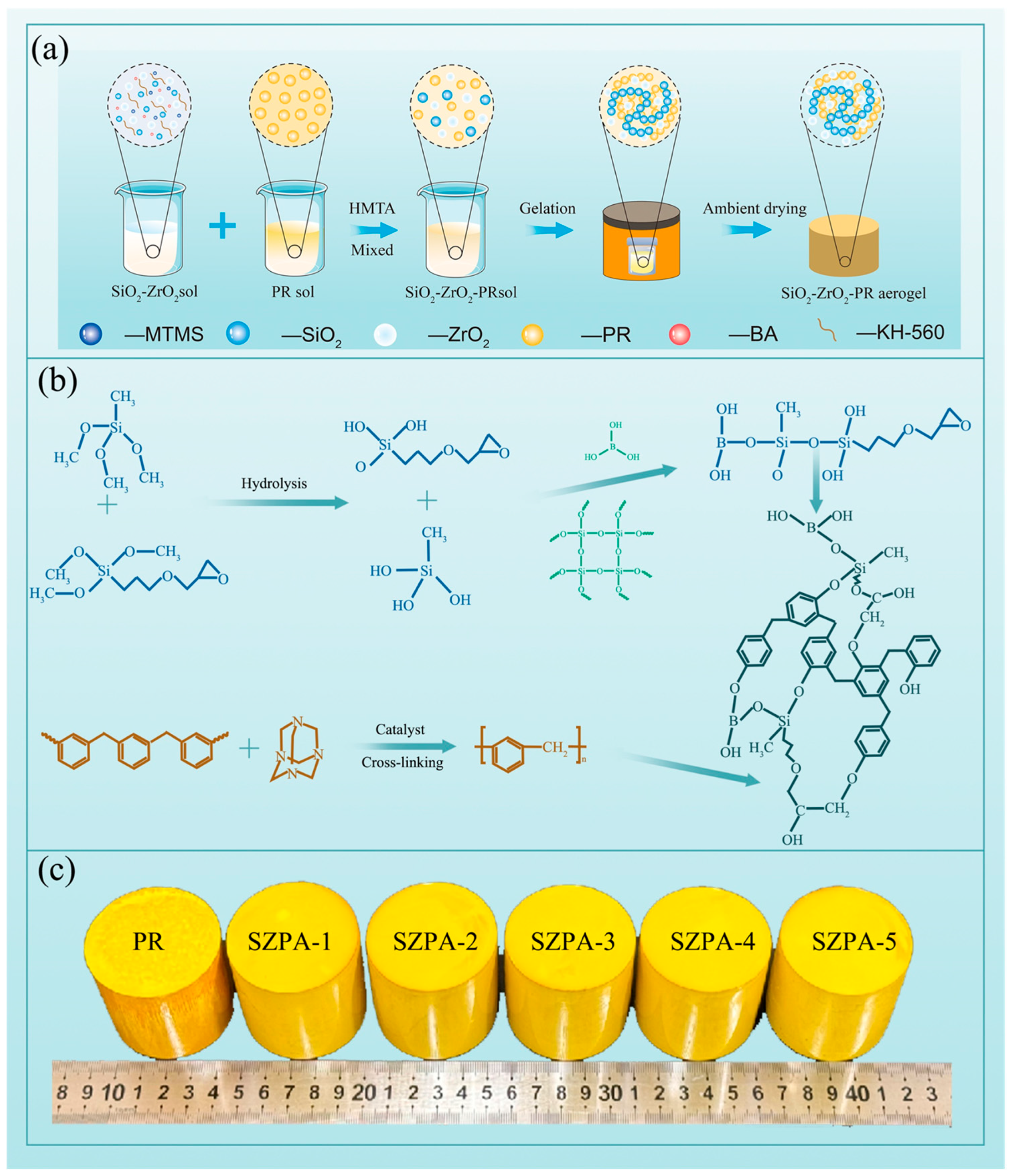

2.1. Synthesis Process

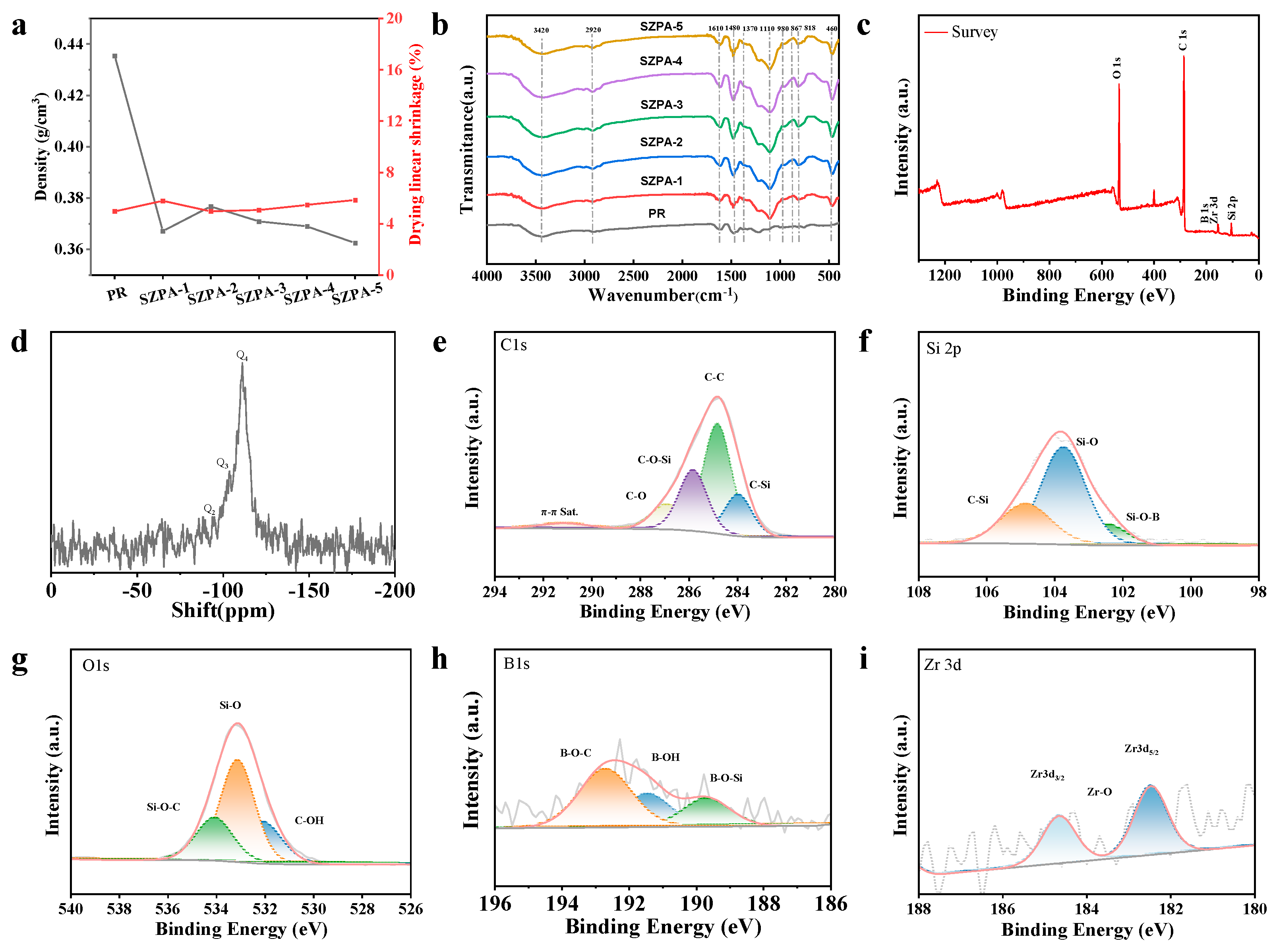

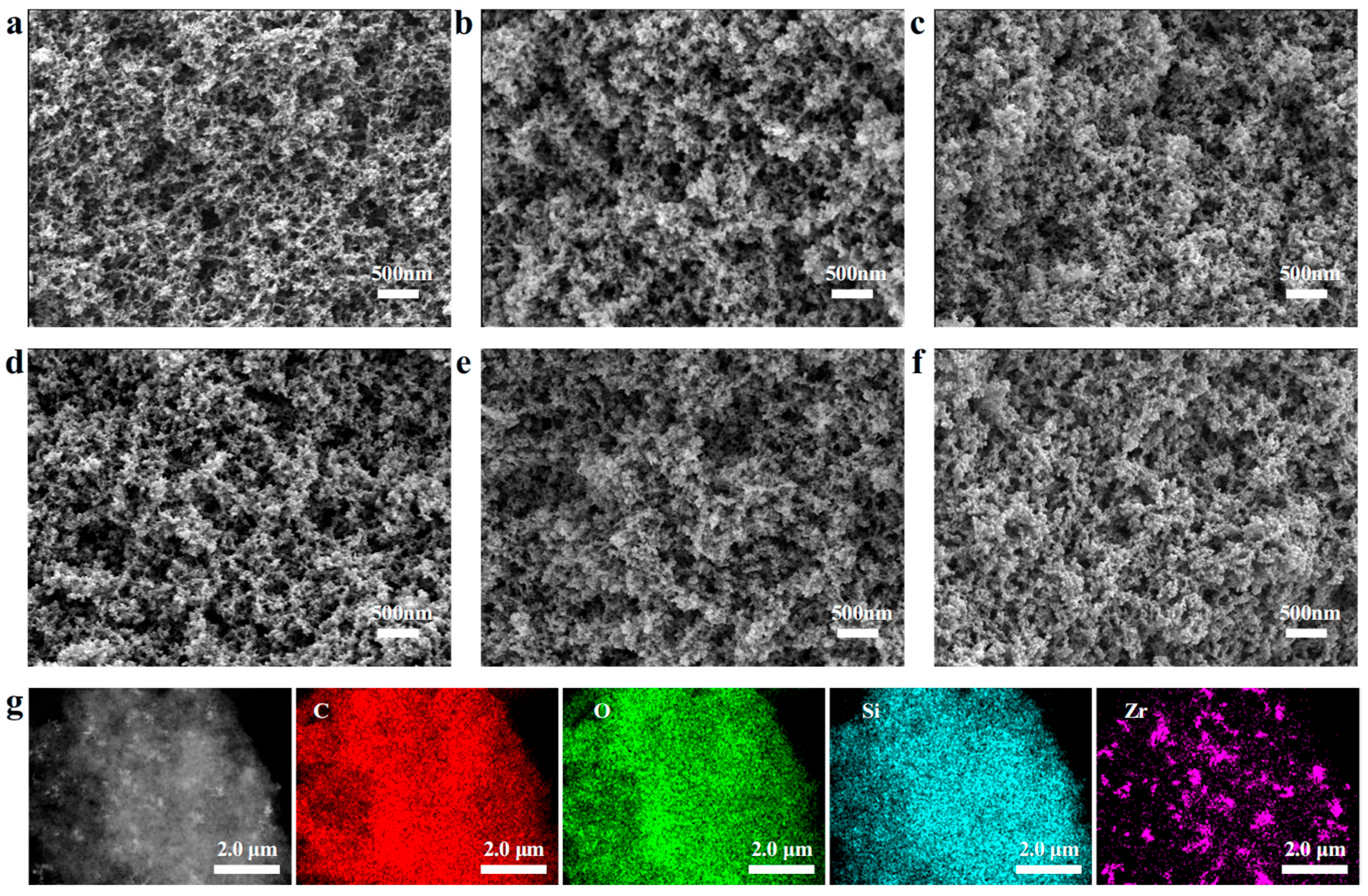

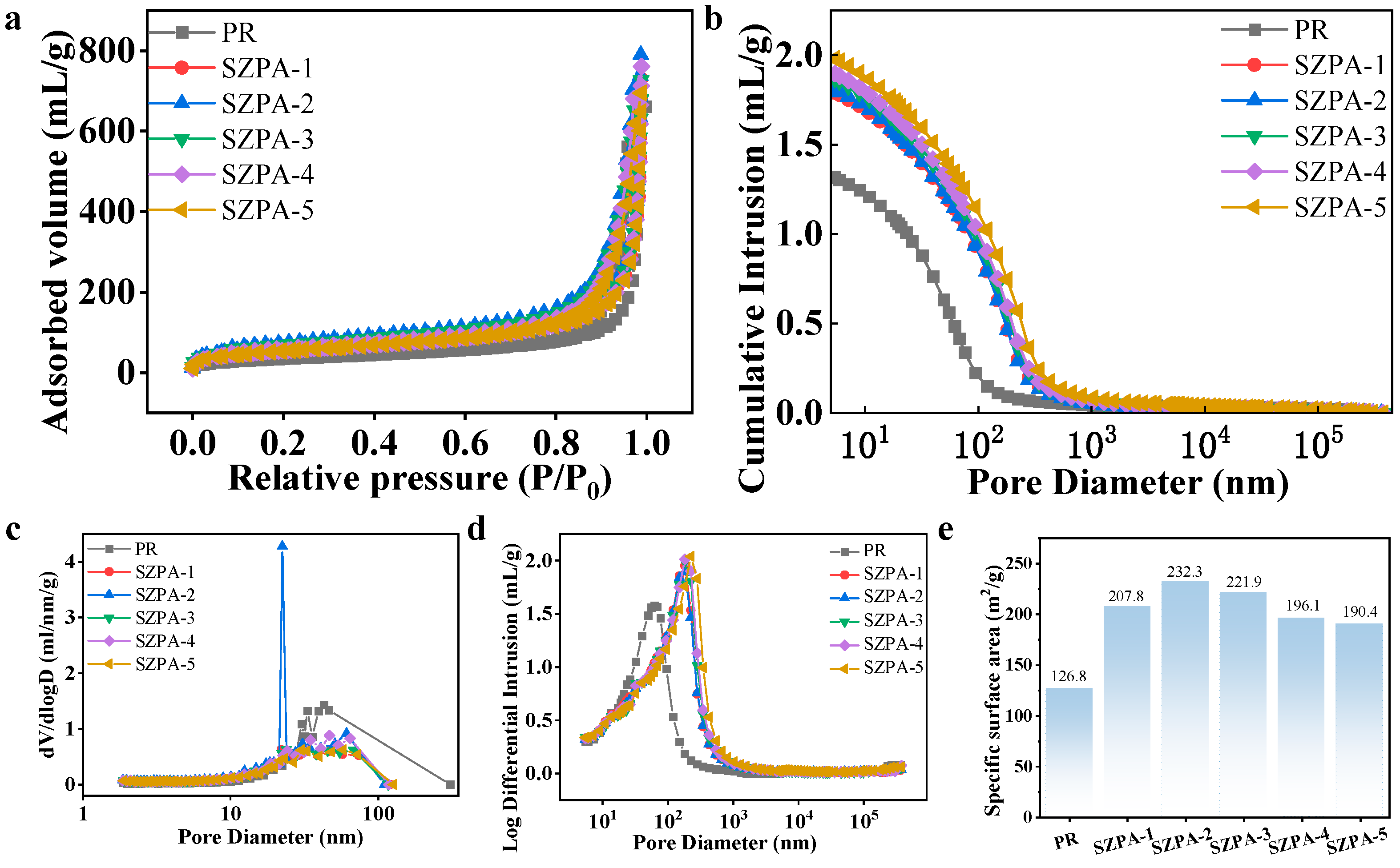

2.2. Morphology and Structure

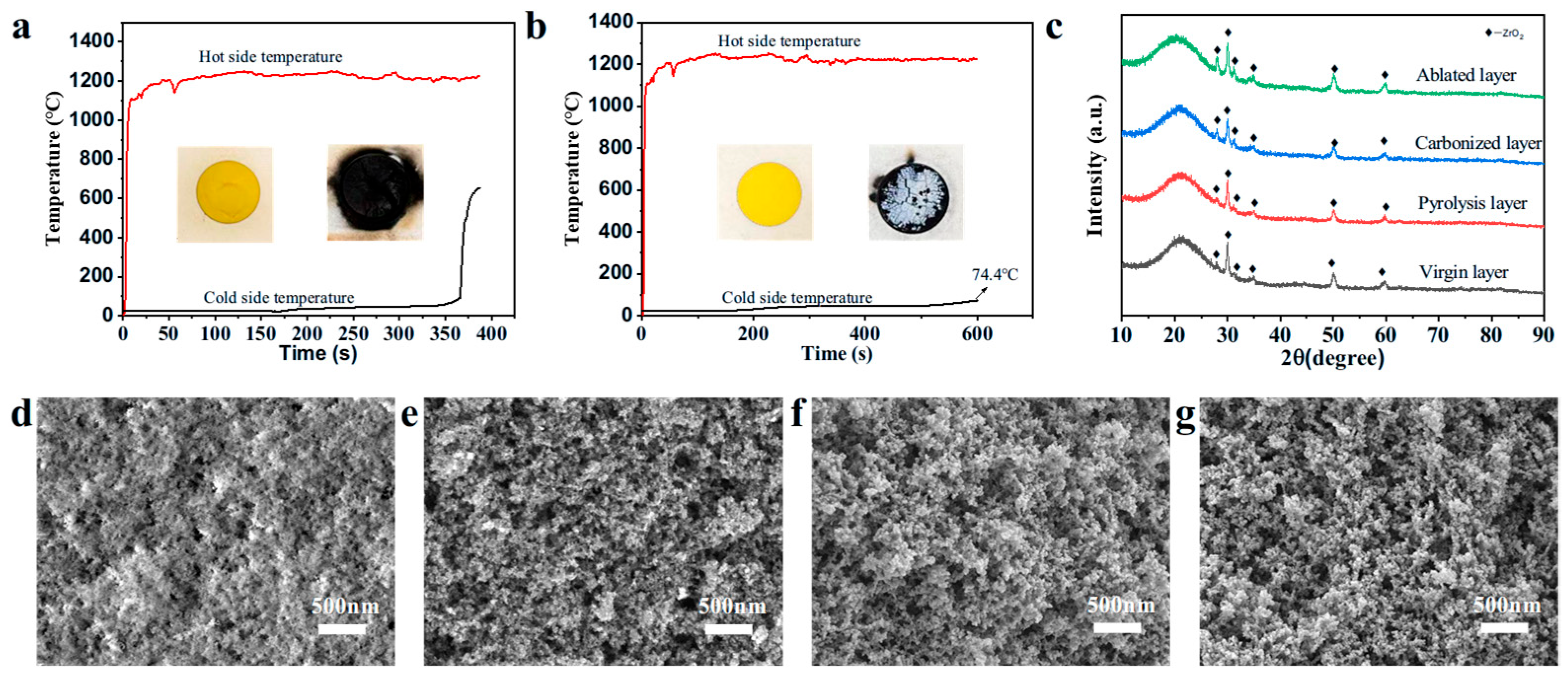

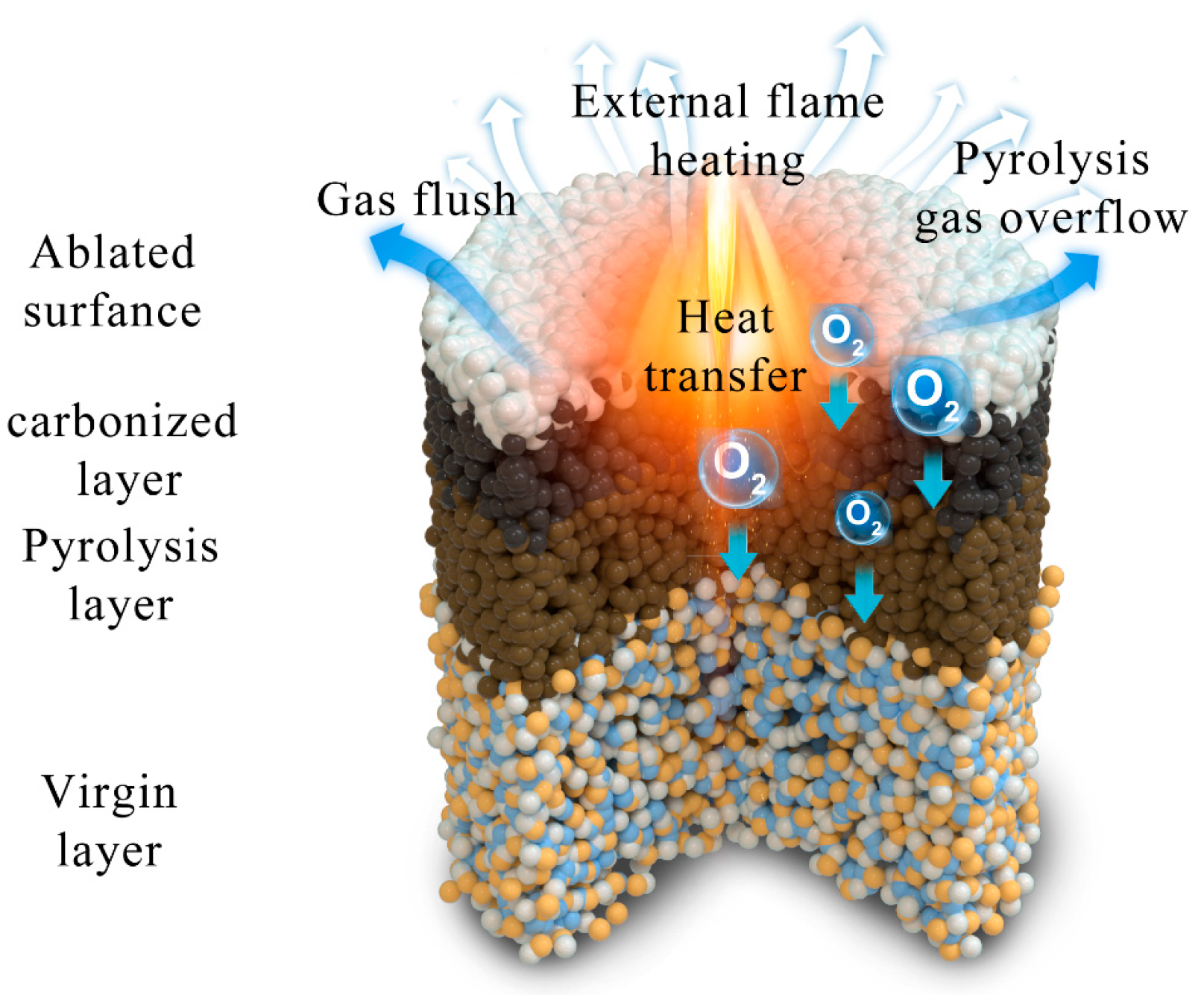

2.3. The Mechanical Properties, Thermal Stability, and Thermal Insulation Properties

3. Conclusions

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Reagents and Materials

4.2. Preparation of SiO2-ZrO2-Phenolic Aerogel (SZPA)

4.3. Sample Characterization

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wu, Q.; Yang, M.; Chen, Z.; Lu, L.; Ma, Z.; Ding, Y.; Yin, L.; Liu, T.; Li, M.; Yang, L.; et al. A Layered Aerogel Composite with Silica Fibers, SiC Nanowires, and Silica Aerogels Ternary Networks for Thermal Insulation at High-Temperature. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2025, 204, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, F.; Jiang, Y.; Feng, J.; Cai, H.; Feng, J.; Li, L. Thermally Insulating, Fiber-Reinforced Alumina–Silica Aerogel Composites with Ultra-Low Shrinkage up to 1500 °C. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 411, 128402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Jiang, Y.; Feng, J.; Li, L.; Hu, Y.; Wang, X.; Feng, J. Robust and Exceptional Thermal Insulating Alumina-Silica Aerogel Composites Reinforced by Ultra IR-Opacified ZrO2 Nanofibers. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 498, 155283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Men, J.; He, C.; Wang, L.; Feng, J.; Jiang, Y.; Li, L.; Hu, Y.; Tang, G.; Feng, J. Synthesis of Structure Controllable Carbon Aerogel with Low Drying Shrinkage and Scalable Size as High-Temperature Thermal Insulator. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 503, 157989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Luo, L.; Zhang, F.; Liu, Y.; Leng, J. Self-Sensing Shape Memory Boron Phenolic-Formaldehyde Aerogels with Tunable Heat Insulation for Smart Thermal Protection Systems. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 505, 159558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantoja, M.; Boynton, N.; Cavicchi, K.A.; Dosa, B.; Cashman, J.L.; Meador, M.A.B. Increased Flexibility in Polyimide Aerogels Using Aliphatic Spacers in the Polymer Backbone. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 9425–9437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Li, L.; Hu, Y.; Liu, F.; Jiang, Y.; Feng, J.; Feng, J. Facile Preparation of Low Shrinkage Polybenzoxazine Aerogels for High Efficiency Thermal Insulation. Sci. China Mater. 2024, 67, 3347–3357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Jin, X.; Wang, H.; Huang, H.; Wu, C.; Yan, X.; Hong, C.; Zhang, X. Nano-TiO2 Coated Needle Carbon Fiber Reinforced Phenolic Aerogel Composite with Low Density, Excellent Heat-Insulating and Infrared Radiation Shielding Performance. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2023, 152, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzapour, A.; Asadollahi, M.H.; Baghshaei, S.; Akbari, M. Effect of Nanosilica on the Microstructure, Thermal Properties and Bending Strength of Nanosilica Modified Carbon Fiber/Phenolic Nanocomposite. Compos. Part A 2014, 63, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulci, G.; Paglia, L.; Genova, V.; Bartuli, C.; Valente, T.; Marra, F. Low Density Ablative Materials Modified by Nanoparticles Addition: Manufacturing and Characterization. Compos. Part A 2018, 109, 330–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azizi, S.; Momen, G.; Ouellet-Plamondon, C.; David, E. Enhancement in Electrical and Thermal Performance of High-temperature Vulcanized Silicone Rubber Composites for Outdoor Insulating Applications. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2020, 137, 49514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Yang, T.; Huang, Z.; Qin, Y.; Wang, Y. Thermal Stability and Ablation Resistance, and Ablation Mechanism of Carbon–Phenolic Composites with Different Zirconium Silicide Particle Loadings. Compos. Part B 2018, 154, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Jin, X.; Huang, H.; Hu, S.; Wu, C.; Wang, H.; Pan, Y.; Hong, C.; Zhang, X. Thermal-Insulation and Ablation-Resistance of Ti-Si Binary Modified Carbon/Phenolic Nanocomposites for High-Temperature Thermal Protection. Compos. Part A 2023, 169, 107528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Jiang, W.; Qian, H.; Shi, X.; Chen, J.; Cao, Q.; Li, N.; Huang, Y.; Jiang, B. Nitrogen-Coordinated Borate Esters Induced Entangled Heterointerface toward Multifunctional Silicone/Phenolic Binary Aerogel Composites. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 482, 149061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Wang, S.; Meng, F.; Wang, Y.; Ma, H. Microencapsulated Ammonium Polyphosphate with Boron-modified Phenolic Resin. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2016, 133, app.43720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Yang, N.; Apostolopoulou-Kalkavoura, V.; Qin, B.; Ma, Z.; Xing, W.; Qiao, C.; Bergström, L.; Antonietti, M.; Yu, S. Fire-Retardant and Thermally Insulating Phenolic-Silica Aerogels. Angew Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 4538–4542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Shen, C.; Wang, Y.; Zhan, L. High-Energy B-O Bonds Enable the Phenolic Aerogel with Enhanced Thermal Stability and Low Thermal Conductivity. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2024, 669, 160459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Z.; Qu, F.; Chen, F.; Ma, X.; Chen, B.; Wang, L.; Xu, M.; Wang, S.; Jin, L.; Zhang, C.; et al. Multifunctional Integrated Organic–Inorganic-Metal Hybrid Aerogel for Excellent Thermal Insulation and Electromagnetic Shielding Performance. Nano-Micro Lett. 2024, 16, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Hong, C.; Jin, X.; Wu, C.; Wang, W.; Wang, H.; Pan, Y.; Wu, S.; Yan, X.; Han, W.; et al. Facile Fabrication of Superflexible and Thermal Insulating Phenolic Aerogels Backboned by Silicone Networks. Compos. Part A 2023, 164, 107270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Wu, C.; Wang, H.; Pan, Y.; Huang, H.; Wang, W.; Fan, J.; Yan, X.; Hong, C.; Zhang, X. Synergistic Reinforcement and Multiscaled Design of Lightweight Heat Protection and Insulation Integrated Composite with Outstanding High-Temperature Resistance up to 2500 °C. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2023, 232, 109878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; Hu, L.; Li, X.; Fan, J.; Liang, J. Preparation and Characterization of Organic-Inorganic Hybrid ZrOC/PF Aerogel Used as High-Temperature Insulator. Ceram. Int. 2020, 46, 6326–6332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Zhang, H.; Gao, X.; Wang, H.; Fang, G.; Wang, B.; Hong, C.; Meng, S. Insight into Pyrolysis Behavior of Silicone-Phenolic Hybrid Aerogel through Thermal Kinetic Analysis and ReaxFF MD Simulations. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 458, 141480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.; Qin, Y.; Peng, Z.; Dou, J.; Huang, Z. A Novel Co-Continuous Si–Zr Hybrid Phenolic Aerogel Composite with Excellent Antioxidant Ablation Enabled by Sea-Island-like Ceramic Structure at High Temperature. Ceram. Int. 2024, 50, 21008–21019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Huang, H.; Jin, X.; Yan, X.; Wang, H.; Pan, Y.; Zhang, X.; Hong, C. Water-Assisted Synthesis of Phenolic Aerogel with Superior Compression and Thermal Insulation Performance Enabled by Thick-United Nano-Structure. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 464, 142805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, L.; Ji, W.; Hao, Q.; Zhang, G.; Meng, Q. Characterization of KH-560-Modified Jute Fabric/Epoxy Laminated Composites: Surface Structure, and Thermal and Mechanical Properties. Polymers 2019, 11, 769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Xiao, Y.; Liu, S.; Li, Z.; Liu, X.; Zhang, S.; Li, Z. Boric Acid-Regulated Gelation and Ethanol-Assisted Preparation of Polybenzoxazine Aerogels. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 486, 150228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Dong, S.; Xin, J.; Liu, C.; Hu, P.; Xia, L.; Hong, C.; Zhang, X. Robust and Thermostable C/SiOC Composite Aerogel for Efficient Microwave Absorption, Thermal Insulation and Flame Retardancy. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 469, 143851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, J.; Chen, L.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, X.; Ye, W.; Zhu, D. Boric Acid as a Coupling Agent for Preparation of Phenolic Resin Containing Boron and Silicon with Enhanced Char Yield. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2018, 40, 1800702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Li, L.; Hu, Y.; Feng, J.; Jiang, Y.; Feng, J. High Mass Residual Silica/Polybenzoxazine Nanoporous Aerogels for High-Temperature Thermal Protection. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2024, 7, 19527–19537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, Y.; Niu, Z.; Shen, S.; Ma, X.; Chen, F.; Wang, L.; Chen, B.; Wang, C.; Zhang, C.; Hou, X. A Novel B–Si–Zr Hybridized Ceramizable Phenolic Resin and the Thermal Insulation Properties of Its Fiber-Reinforced Composites. Ceram. Int. 2023, 49, 4919–4928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Q.; Liu, X.; Ou, Y.; Zhong, Y.; Wu, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Cui, S. Chemical Design and Microphase Separation of Silicone/Phenolic Resin Double-Network Aerogels for Superior Flexibility and Thermal Insulation. Compos. Part A 2025, 198, 109161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Deng, Z.; Huang, Z.; Shi, M. Synthesis and Characterization of Novel Phenolic Resin/Siloxane Aerogels via Ambient Pressure Drying. J. Macromol. Sci. B 2023, 62, 621–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Ye, L.; Zhao, T.; Li, H. Microphase Separation Regulation of Polyurethane Modified Phenolic Resin Aerogel to Enhance Mechanical Properties and Thermal Insulation. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 495, 153532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Xu, G.; Ji, H.; Zhang, H.; Wang, J.; Lu, K.; Wang, Z.; Yang, Z.; Liu, Z.; Xin, W.; et al. Thermally Insulating Polybenzoxazine/Nanosilica Aerogel Ablation Resistant to 1100 °C for Re-Entry Capsules. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2023, 5, 8223–8234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, S.S.; Tiwari, J.; Rai, A.; Hun, D.E.; Howard, D.; Desjarlais, A.O.; Francoeur, M.; Feng, T. Solid and Gas Thermal Conductivity Models Improvement and Validation in Various Porous Insulation Materials. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2023, 187, 108164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichenauer, G.; Heinemann, U.; Ebert, H.-P. Relationship between Pore Size and the Gas Pressure Dependence of the Gaseous Thermal Conductivity. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2007, 300, 204–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Fang, G.; Jin, X.; Wang, B.; Meng, S. A Comprehensive Study of Pyrolysis Characteristics of Silicone-Modified Phenolic Aerogel Matrix Nanocomposites: Kinetic Analysis, ReaxFF MD Simulations, and ANN Prediction. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 472, 145049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Rodríguez, J.; Kalmár, J.; Menelaou, M.; Čelko, L.; Dvořak, K.; Cihlář, J.; Cihlař, J.; Kaiser, J.; Győri, E.; Veres, P.; et al. Heat Treatment Induced Phase Transformations in Zirconia and Yttria-Stabilized Zirconia Monolithic Aerogels. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2019, 149, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, S.; Deng, Z.; Huang, Z.; Shi, M.; Lu, Y. Ablation Behavior and High Temperature Ceramization Mechanism of TiB2-B4C-ZrC Modified Carbon Fiber/Boron Phenolic Resin Composites. Ceram. Int. 2024, 50, 46173–46186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Compressive Strength (MPa) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 3% ε | 5% ε | 10% ε | |

| PR | 4.49 | 8.57 | 13.54 |

| SZPA-1 | 1.79 | 3.26 | 4.95 |

| SZPA-2 | 1.70 | 3.07 | 4.92 |

| SZPA-3 | 1.62 | 3.02 | 4.74 |

| SZPA-4 | 1.05 | 2.52 | 4.42 |

| SZPA-5 | 0.98 | 2.10 | 3.62 |

| Samples | Silica Sol (mL) | Nano-Zirconia (mL) | MTMS (mL) | KH-560 (mL) | Boric Acid (g) | PR (g) | EtOH (mL) | HMTA (g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PR | / | / | / | / | / | 48 | 120 | 9.6 |

| SZPA-1 | 100 | 2.5 | 5.6 | 0.5 | 1.5 | 48 | 120 | 9.6 |

| SZPA-2 | 100 | 7.6 | 5.6 | 0.7 | 1.8 | 48 | 120 | 9.6 |

| SZPA-3 | 100 | 12.6 | 5.6 | 0.9 | 2.0 | 48 | 120 | 9.6 |

| SZPA-4 | 100 | 17.7 | 5.6 | 1.2 | 2.5 | 48 | 120 | 9.6 |

| SZPA-5 | 100 | 25.3 | 5.6 | 1.5 | 2.5 | 48 | 120 | 9.6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhan, Y.; Zhang, C.; Li, L.; Huang, M.; Chen, S.; Jiang, Y.; Feng, J.; Hu, Y.; Feng, J. A Novel Phenolic Resin Aerogel Modified by SiO2-ZrO2 for Efficient Thermal Protection and Insulation. Gels 2025, 11, 1018. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11121018

Zhan Y, Zhang C, Li L, Huang M, Chen S, Jiang Y, Feng J, Hu Y, Feng J. A Novel Phenolic Resin Aerogel Modified by SiO2-ZrO2 for Efficient Thermal Protection and Insulation. Gels. 2025; 11(12):1018. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11121018

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhan, Yifan, Chunhui Zhang, Liangjun Li, Mengle Huang, Sian Chen, Yonggang Jiang, Junzong Feng, Yijie Hu, and Jian Feng. 2025. "A Novel Phenolic Resin Aerogel Modified by SiO2-ZrO2 for Efficient Thermal Protection and Insulation" Gels 11, no. 12: 1018. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11121018

APA StyleZhan, Y., Zhang, C., Li, L., Huang, M., Chen, S., Jiang, Y., Feng, J., Hu, Y., & Feng, J. (2025). A Novel Phenolic Resin Aerogel Modified by SiO2-ZrO2 for Efficient Thermal Protection and Insulation. Gels, 11(12), 1018. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11121018