The Influence of Synthesis Parameters on the Properties of Dextran-Based Hydrogels for Colon-Targeted Antitumor Drug Delivery Part I: Room Temperature Synthesis of Dextran/Inulin Hydrogels for Colon-Targeted Antitumor Drug Delivery

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Results of FTIR Analysis

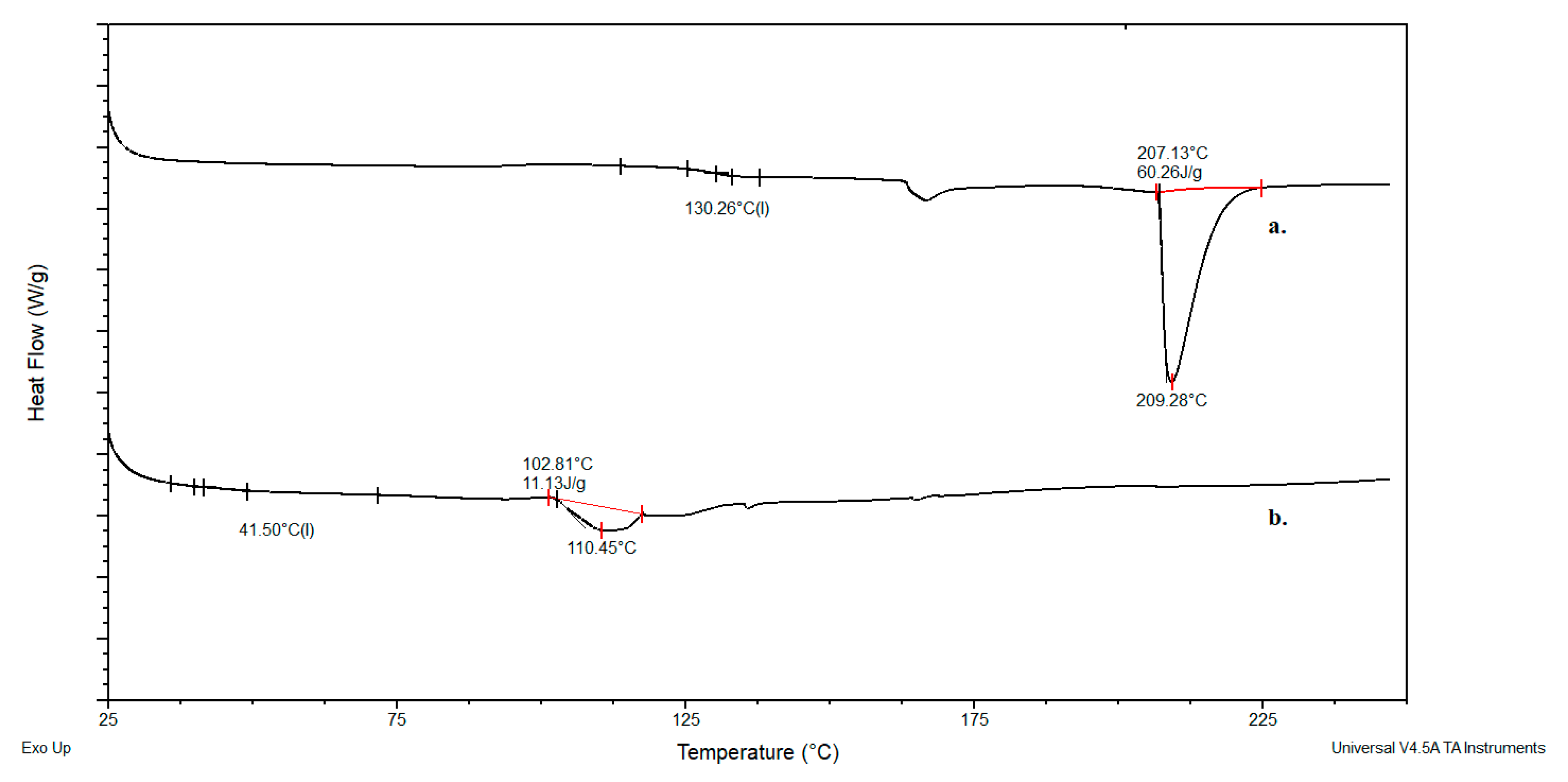

2.2. Results of DSC Analysis

2.3. Results of SEM Analysis

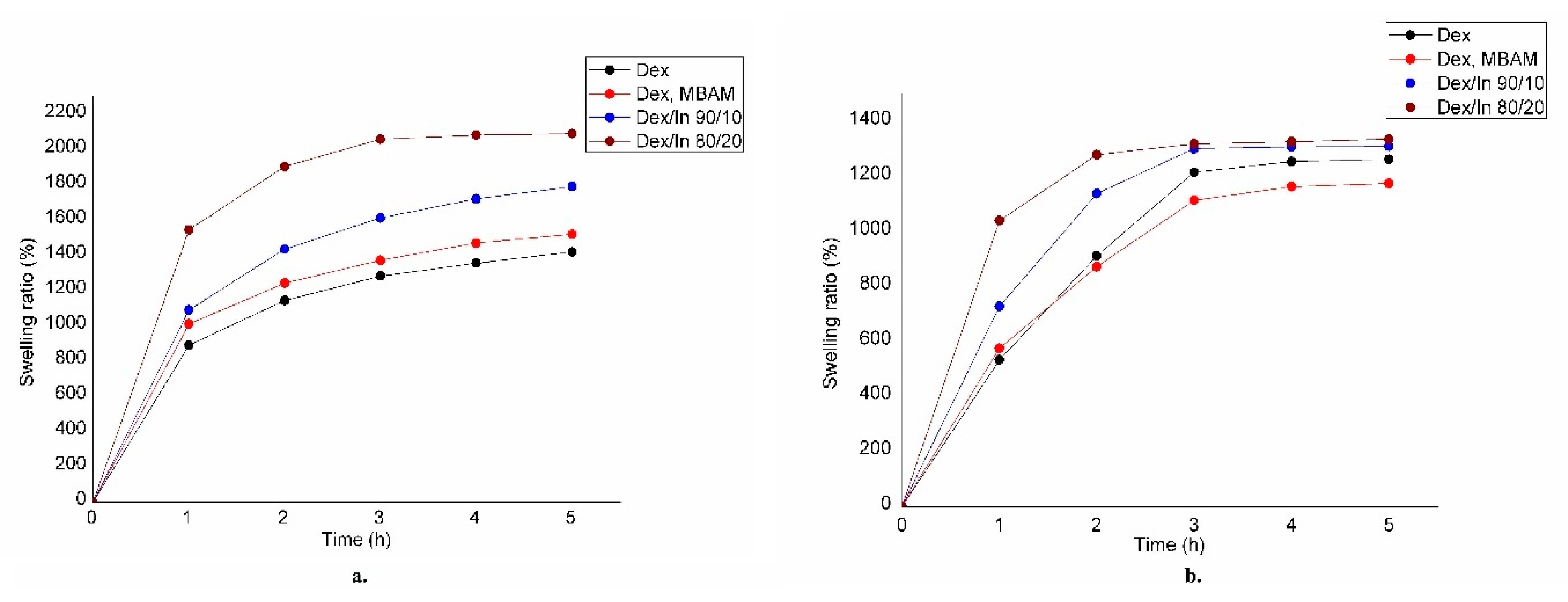

2.4. Results of Swelling Analysis

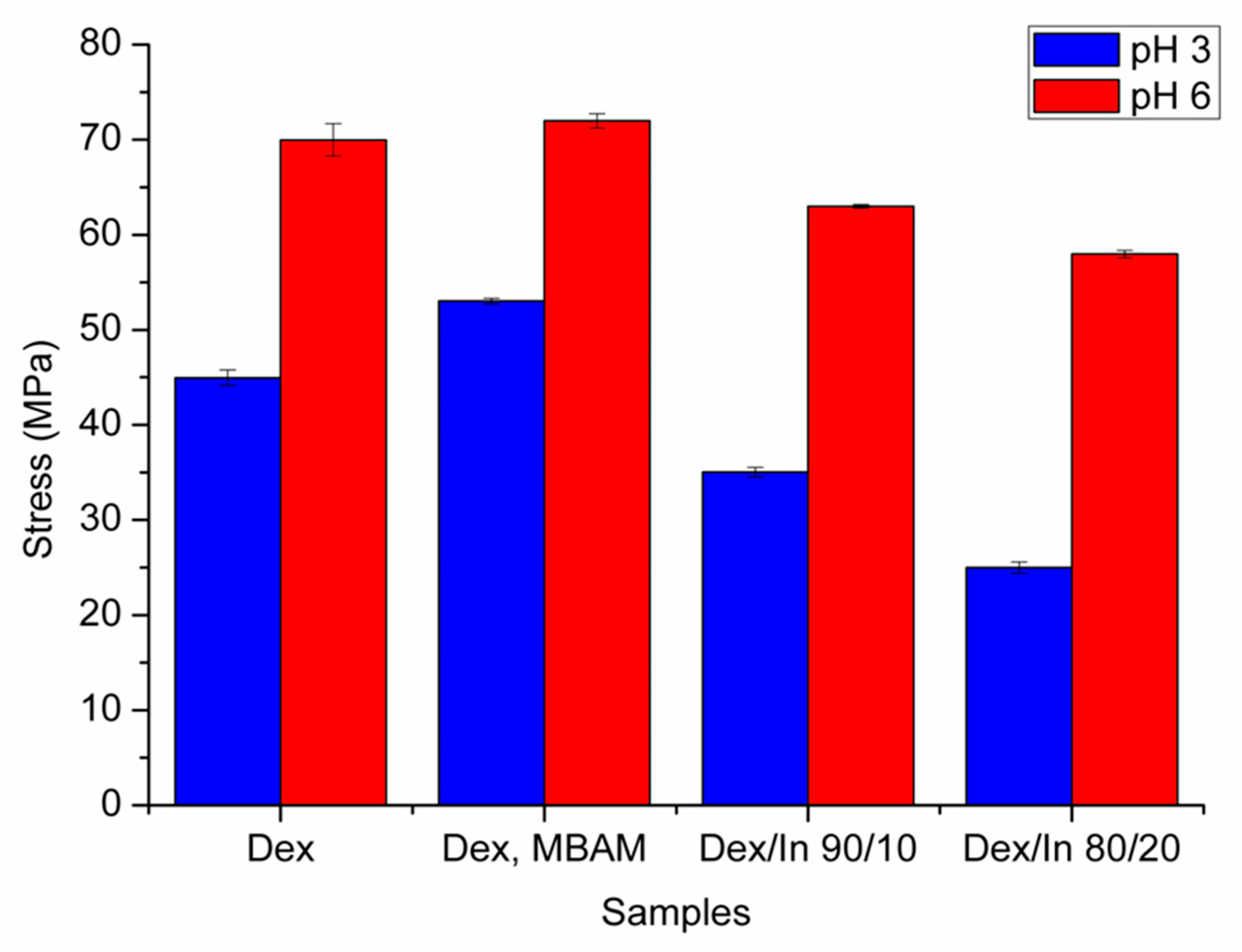

2.5. Results of Mechanical Analysis

2.6. Results of In Vitro Gastrointestinal Digestion (GID)

2.7. Results of Encapsulation Efficiency (EE) Determination

3. Conclusions

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

4.2. Preparation of Hydrogels

4.3. Infrared Spectroscopy with Fourier Transformation (FTIR) Analysis

4.4. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) Analysis

4.5. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) Analysis

4.6. Analysis of Swelling Properties

4.7. Analysis of Mechanical Properties

4.8. Simulated In Vitro Gastrointestinal Digestion (GID)

4.9. Determination of Uracil Concentration in Digestate by UV/VIS Spectrophotometry

4.10. Determination of Encapsulation Efficiency

4.11. Statistical Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DMF | Dimethylformamide |

| MA | Methacrylic acid |

| IN-MA | Inulin metahcrylate |

| BMAAB | bis(methacryloylamino)azobenzene |

| HEMA | 2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate |

| Dex–MA | Dextran-methacrylate |

| EPR | Enhanced permeability and retention |

| FTIR | Infrared spectroscopy with Fourier transformation |

| DSC | Differential scanning calorimetry |

| DMSO | Dimethyl sulfoxide |

| MBAM | N, N′-Methylenebis (acrylamide) |

| TEMED | N,N,N’,N’-Tetramethylethylenediamine |

| PPS | Potassium persulfate |

| SIF | Simulated intestinal fluid |

| SGF | Simulated gastric fluid |

| EE | Encapsulation efficiency |

References

- Prieložná, J.; Mikušová, V.; Mikuš, P. Advances in the Delivery of Anticancer Drugs by Nanoparticles and Chitosan-Based Nanoparticles. Int. J. Pharm. X 2024, 8, 100281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinde, V.R.; Revi, N.; Murugappan, S.; Singh, S.P.; Rengan, A.K. Enhanced Permeability and Retention Effect: A Key Facilitator for Solid Tumor Targeting by Nanoparticles. Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther. 2022, 39, 102915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behranvand, N.; Nasri, F.; Zolfaghari Emameh, R.; Khani, P.; Hosseini, A.; Garssen, J.; Falak, R. Chemotherapy: A Double-Edged Sword in Cancer Treatment. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2022, 71, 507–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.X.; Wong, H.L.; Xue, H.Y.; Eoh, J.Y.; Wu, X.Y. Nanomedicine of Synergistic Drug Combinations for Cancer Therapy—Strategies and Perspectives. J. Control. Release 2016, 240, 489–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baweja, R.; Ravi, R.; Baweja, R.; Gupta, S.; Sachan, A.; Pratyusha, V.; Warsi, M.K.; Purohit, S.D.; Mishra, A.; Ahmad, R. A Comprehensive Review of Hydrogels as Potential Drug Carriers for Anticancer Therapies: Properties, Development and Future Prospects. Next Mater. 2025, 8, 100913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erceg, T.; Vukić, N. Architecture of Hydrogels. In Fundamentals to Advanced Energy Applications; Kumar, A., Gupta, R., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malfanti, A.; Catania, G.; Degros, Q.; Wang, M.; Bausart, M.; Préat, V. Design of Bio-Responsive Hyaluronic Acid–Doxorubicin Conjugates for the Local Treatment of Glioblastoma. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheng, Y.; Gao, J.; Yin, Z.-Z.; Kang, J.; Kong, Y. Dual-Drug Delivery System Based on the Hydrogels of Alginate and Sodium Carboxymethyl Cellulose for Colorectal Cancer Treatment. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 269, 118325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaganova, S.O.; Khalashevskaya, D.D.; Efremov, Y.M.; Timashev, P.S.; Burmistrov, I.A.; Puchkov, A.A.; Trushina, D.B. Properties of Sodium Alginate-Based Hydrogels Cross-Linked with Calcium and Iron Cations. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2025, 74, 1312–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udaipuria, N.; Bhattacharya, S. Novel Carbohydrate Polymer-Based Systems for Precise Drug Delivery in Colon Cancer: Improving Treatment Effectiveness with Intelligent Biodegradable Materials. Biopolymers 2024, 116, e23632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haeberlin, B.; Friend, D.R. Anatomy and Physiology of the Gastrointestinal Tract: Implications for Colonic Drug Delivery. In Oral Colon-Specific Drug Delivery; Friend, D.R., Ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, K.; Yang, X.; He, L.; Zheng, R.; Min, J.; Su, H.; Shan, S.; Jia, Q. Facile Preparation of pH/Reduction Dual-Stimuli Responsive Dextran Nanogel as Environment-Sensitive Carrier of Doxorubicin. Polymer 2020, 200, 122585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hovgaard, L.; Brøndsted, H. Dextran Hydrogels for Colon-Specific Drug Delivery. J. Control. Release 1995, 36, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonsen, L.; Hovgaard, L.; Mortensen, P.B.; Brøndsted, H. Dextran Hydrogels for Colon-Specific Drug Delivery. V. Degradation in Human Intestinal Incubation Models. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 1995, 3, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripodo, G.; Pitarresi, G.; Palumbo, F.S.; Craparo, E.F.; Giammona, G. UV-Photocrosslinking of Inulin Derivatives to Produce Hydrogels for Drug Delivery Application. Macromol. Biosci. 2005, 5, 1113–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afinjuomo, F.; Barclay, T.G.; Song, Y.; Parikh, A.; Petrovsky, N.; Garg, S. Synthesis and Characterization of a Novel Inulin Hydrogel Crosslinked with Pyromellitic Dianhydride. React. Funct. Polym. 2019, 134, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vervoort, L.; Van den Mooter, G.; Augustijns, P.; Busson, R.; Toppet, S.; Kinget, R. Inulin Hydrogels as Carriers for Colonic Drug Targeting: I. Synthesis and Characterization of Methacrylated Inulin and Hydrogel Formation. Pharm. Res. 1997, 14, 1730–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Mooter, G.; Vervoort, L.; Kinget, R. Characterization of Methacrylated Inulin Hydrogels Designed for Colon Targeting: In Vitro Release of BSA. Pharm. Res. 2003, 20, 303–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maris, B.; Verheyden, L.; Van Reeth, K.; Samyn, C.; Augustijns, P.; Kinget, R.; Van den Mooter, G. Synthesis and Characterisation of Inulin-Azo Hydrogels Designed for Colon Targeting. Int. J. Pharm. 2001, 213, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vettori, M.H.P.B.; Franchetti, S.M.M.; Contiero, J. Structural characterization of a new dextran with a low degree of branching produced by Leuconostoc mesenteroides FT045B dextransucrase. Carbohydr. Polym. 2012, 88, 1440–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ağagündüz, D.; Özata-Uyar, G.; Kocaadam-Bozkurt, B.; Özturan-Şirin, A.; Capasso, R.; Al-Assaf, S.; Özoğul, F. A comprehensive review on food hydrocolloids as gut modulators in the food matrix and nutrition: The hydrocolloid-gut-health axis. Food Hydrocoll. 2023, 145, 109068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensink, M.A.; Frijlink, H.W.; van der Voort Maarschalk, K.; Hinrichs, W.L.J. Inulin, a Flexible Oligosaccharide I: Review of Its Physicochemical Characteristics. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015, 130, 405–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, W.A.; Piazentin, A.C.M.; da Silva, T.M.S.; Mendonça, C.M.N.; Figueroa Villalobos, E.; Converti, A.; Oliveira, R.P.S. Alternative Fermented Soy-Based Beverage: Impact of Inulin on the Growth of Probiotic Strains and Starter Culture. Fermentation 2023, 9, 961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul Khalil, H.P.S.; Yahya, E.B.; Tajarudin, H.A.; Balakrishnan, V.; Nasution, H. Insights into the Role of Biopolymer-Based Xerogels in Biomedical Applications. Gels 2022, 8, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paoletti, L.; Ferrigno, G.; Zoratto, N.; Secci, D.; Di Meo, C.; Matricardi, P. Reinforcement of Dextran Methacrylate-Based Hydrogel, Semi-IPN, and IPN with Multivalent Crosslinkers. Gels 2024, 10, 773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, I.Y.; Bala, S.; Škalko-Basnet, N.; di Cagno, M.P. Interpreting non-linear drug diffusion data: Utilizing Korsmeyer–Peppas model to study drug release from liposomes. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2019, 138, 105026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Smedt, S.C.; Lauwers, A.; Demeester, J.; Van Steenbergen, M.J.; Hennink, W.E.; Roefs, S.P.F.M. Characterization of the Network Structure of Dextran Glycidyl Methacrylate Hydrogels by Studying the Rheological and Swelling Behavior. Macromolecules 1995, 28, 5082–5088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D3644-15(2022); Standard Test Method for Acid Number of Styrene-Maleic Anhydride Resins. ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2022. [CrossRef]

- ISO 3657:2023; Animal and Vegetable Fats and Oils—Determination of Saponification Value; Edition 6. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023.

- ASTM E11-20; Standard Specification for Woven Wire Test Sieve Cloth and Test Sieves. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2022.

- Brodkorb, A.; Egger, L.; Alminger, M.; Alvito, P.; Assunção, R.; Ballance, S.; Bohn, T.; Bourlieu-Lacanal, C.; Boutrou, R.; Carrière, F.; et al. INFOGEST Static In Vitro Simulation of Gastrointestinal Food Digestion. Nat. Protoc. 2019, 14, 991–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kostić, A.Ž.; Milinčić, D.D.; Stanisavljević, N.S.; Gašić, U.M.; Lević, S.; Kojić, M.O.; Tešić, Ž.L.; Nedović, V.; Barać, M.B.; Pešić, M.B. Polyphenol Bioaccessibility and Antioxidant Properties of In Vitro Digested Spray-Dried Thermally-Treated Skimmed Goat Milk Enriched with Pollen. Food Chem. 2021, 351, 129310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khajehsharifi, H.; Soleimanzadegan, S. Partial Least Squares Method for Simultaneous Spectrophotometric Determination of Uracil and 5-Fluorouracil in Spiked Biological Samples. Appl. Chem. Today 2013, 7, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Călina, I.; Demeter, M.; Scărișoreanu, A.; Sătulu, V.; Mitu, B. One Step e-Beam Radiation Cross-Linking of Quaternary Hydrogels Dressings Based on Chitosan-Poly(Vinyl-Pyrrolidone)-Poly(Ethylene Glycol)-Poly(Acrylic Acid). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 9236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omidian, H.; Gill, E.J.; Cubeddu, L.X. Lipid Nanoparticles in Lung Cancer Therapy. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Uracil-Loaded Hydrogels | Gastric Phase Release, µg/mL | Intestinal Phase Release, µg/mL | Gastric Phase Release, % | Intestinal Phase Release, % | Total Released Amount of Drug, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dex | 19.46 ±0.57 c | 80.21 ± 0.72 c | 16.57 ± 0.46 c | 64.17 ± 0.57 c | 80.74 ± 0.73 c |

| Dex, MBAM | 16.81 ± 0.28 b | 87.29 ± 0.51 d | 13.45 ± 0.23 b | 69.84 ± 2.07 d | 83.29 ± 2.08 c |

| Dex/In 90/10 | 0 ± 0.00 a | 75.47 ± 1.85 b | 0 ± 0.00 a | 60.37 ± 2.08 b | 60.37 ± 2.08 b |

| Dex/In 80/20 | 0 ± 0.00 a | 59.71 ± 1.85 a | 0 ± 0.00 a | 47.76 ± 2.49 a | 47.76 ± 2.49 a |

| Uracil-Loaded Hydrogels | n | k | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dex | 2.66 | 0.03 | 0.92 |

| Dex, MBAM | 1.59 | 0.09 | 0.91 |

| Uracil-Loaded Hydrogels | Encapsulation Efficiency (%) |

|---|---|

| Dex | 90.10 ± 1.45 a |

| Dex, MBAM | 91.63 ± 1.16 a |

| Dex/In 90/10 | 89.98 ± 0.45 a |

| Dex/In 80/20 | 88.89 ± 1.59 a |

| Samples | Dextran–MA 1, g | Inulin–MA 2, g |

|---|---|---|

| Dex | 1 | 0 |

| Dex, MBAM | 1 | 0 |

| Dex/In 90/10 | 0.9 | 0.1 |

| Dex/In 80/20 | 0.8 | 0.2 |

| SGF | SIF | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH 3.0 | pH 7.0 | |||

| Compound | Stock Conc. | Conc. in SGF | Conc. in SIF | |

| g/L | mol/L | mmol/L | mmol/L | |

| KCl | 37.3 | 0.5 | 6.9 | 6.8 |

| KH2PO4 | 68 | 0.5 | 0.9 | 0.8 |

| NaHCO3 | 84 | 1 | 25 | 85 |

| NaCl | 117 | 2 | 47.2 | 38.4 |

| MgCl2·6H2O | 30.5 | 0.15 | 0.1 | 0.33 |

| (NH4)2CO3 | 48 | 0.5 | 0.5 | - |

| NaOH | - | 1 | - | 8.4 |

| HCl | - | 6 | 15.6 | - |

| CaCl2 2H2O | 44.1 | 0.3 | 0.075 | 0.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Erceg, T.; Radosavljević, M.; Miljić, M.; Cvetanović Kljakić, A.; Baloš, S.; Špoljarić, K.M.; Ćorić, I.; Glavaš-Obrovac, L.; Torbica, A. The Influence of Synthesis Parameters on the Properties of Dextran-Based Hydrogels for Colon-Targeted Antitumor Drug Delivery Part I: Room Temperature Synthesis of Dextran/Inulin Hydrogels for Colon-Targeted Antitumor Drug Delivery. Gels 2025, 11, 1011. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11121011

Erceg T, Radosavljević M, Miljić M, Cvetanović Kljakić A, Baloš S, Špoljarić KM, Ćorić I, Glavaš-Obrovac L, Torbica A. The Influence of Synthesis Parameters on the Properties of Dextran-Based Hydrogels for Colon-Targeted Antitumor Drug Delivery Part I: Room Temperature Synthesis of Dextran/Inulin Hydrogels for Colon-Targeted Antitumor Drug Delivery. Gels. 2025; 11(12):1011. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11121011

Chicago/Turabian StyleErceg, Tamara, Miloš Radosavljević, Milorad Miljić, Aleksandra Cvetanović Kljakić, Sebastian Baloš, Katarina Mišković Špoljarić, Ivan Ćorić, Ljubica Glavaš-Obrovac, and Aleksandra Torbica. 2025. "The Influence of Synthesis Parameters on the Properties of Dextran-Based Hydrogels for Colon-Targeted Antitumor Drug Delivery Part I: Room Temperature Synthesis of Dextran/Inulin Hydrogels for Colon-Targeted Antitumor Drug Delivery" Gels 11, no. 12: 1011. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11121011

APA StyleErceg, T., Radosavljević, M., Miljić, M., Cvetanović Kljakić, A., Baloš, S., Špoljarić, K. M., Ćorić, I., Glavaš-Obrovac, L., & Torbica, A. (2025). The Influence of Synthesis Parameters on the Properties of Dextran-Based Hydrogels for Colon-Targeted Antitumor Drug Delivery Part I: Room Temperature Synthesis of Dextran/Inulin Hydrogels for Colon-Targeted Antitumor Drug Delivery. Gels, 11(12), 1011. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11121011