Structural Features and Mechanical Properties of Hydrogels Based on PVP Copolymers, Obtained in the Presence of a Solvent

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

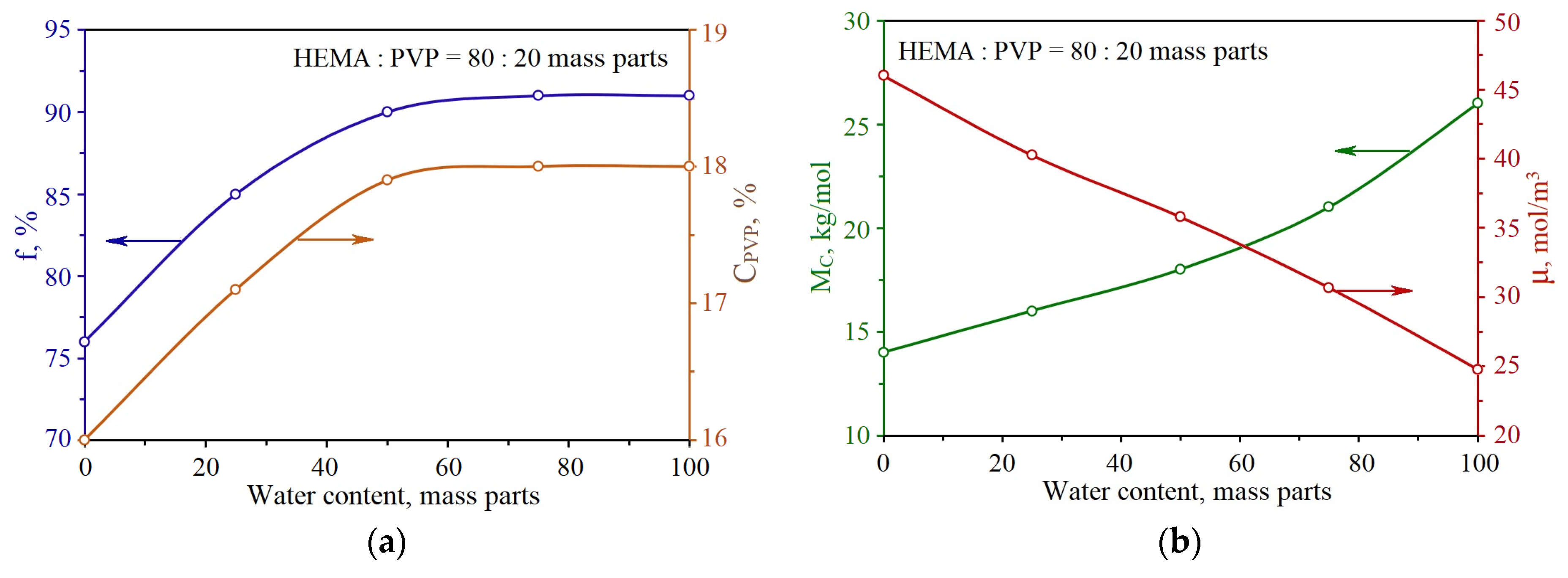

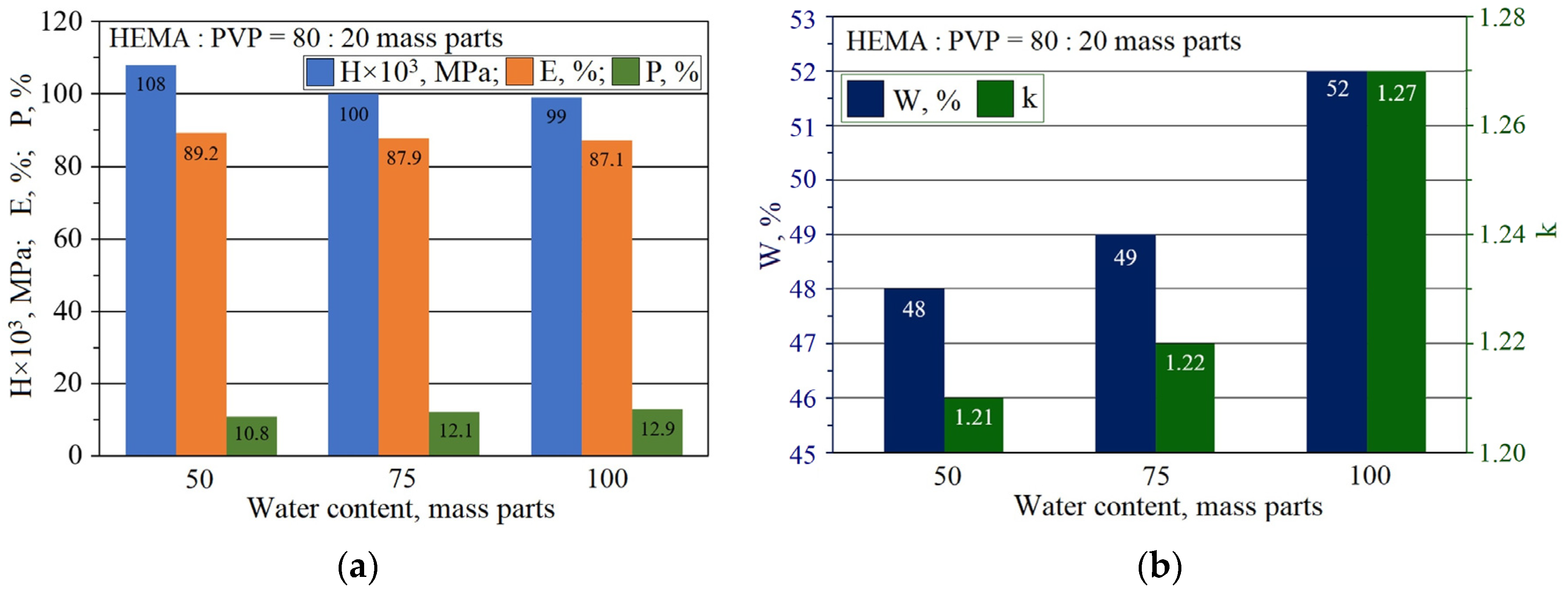

2.1. Research of the Structure and Formulation of HEMA with PVP Copolymers Obtained by Polymerization in the Presence of a Solvent

2.2. The Properties of pHEMA-gr-PVP Copolymers

3. Conclusions

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

- –

- 2-hydroxyethylmethacrylate (Sigma Chemical Co., Saint Louis, MO, USA) after purification via vacuum distillation was conducted at a residual pressure of 130 N/m2 and a boiling temperature of 351 K;

- –

- Polyvinylpyrrolidone (AppliChem GmbH, Darmstadt, Germany) with a molecular weight of 28,000 was dried under vacuum at 338 K for 2–3 h prior to its application;

- –

- Iron (II) sulfate (FeSO4) was employed as pro analysis (p.a.) grade reagent.

4.2. pHEMA-gr-PVP Copolymer Synthesis

4.3. Measurements and Characterization

4.3.1. Standard Methods of Instrumental Research

4.3.2. Measurement of the Dynamic Viscosity of Solutions

4.3.3. Efficiency of PVP Grafting

4.3.4. Structural Parameters of the Polymer Network

4.3.5. Physico-Mechanical Characteristics of pHEMA-gr-PVP Copolymers

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HEMA | 2-hydroxyethylmethacrylate |

| PVP | Polyvinylpyrrolidone |

| DMSO | Dimethyl sulfoxide |

| DEG | Diethylene glycol |

| HOCy | Cyclohexanol |

| MPC | Monomer–polymer composition |

References

- Ho, T.C.; Chang, C.C.; Chan, H.P.; Chung, T.W.; Shu, C.W.; Chuang, K.P.; Duh, T.H.; Yang, M.H.; Tyan, Y.C. Hydrogels: Properties and Applications in Biomedicine. Molecules 2022, 27, 2902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Cid, P.; Jiménez-Rosado, M.; Romero, A.; Pérez-Puyana, V. Novel Trends in Hydrogel Development for Biomedical Applications: A Review. Polymers 2022, 14, 3023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, L.; Huang, J. Recent Progress in Hydrogel Synthesis and Biomedical Applications. Gels 2025, 11, 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naahidi, S.; Jafari, M.; Logan, M.; Wang, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Bae, H.; Dixon, B.; Chen, P. Biocompatibility of hydrogel-based scaffolds for tissue engineering applications. Biotechnol. Adv. 2017, 35, 530–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Liu, M.; Zhang, Y.; Yin, J.; Pei, R. Nanocomposite hydrogels for tissue engineering applications. Nanoscale 2020, 12, 14976–14995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, P.; De Marco, I. Contact lenses as ophthalmic drug delivery systems: A review. Polymers 2021, 13, 1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchhof, S.; Goepferich, A.M.; Brandl, F.P. Hydrogels in ophthalmic applications. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2015, 95, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigata, M.; Meinert, C.; Hutmacher, D.W.; Bock, N. Hydrogels as drug delivery systems: A review of current characterization and evaluation techniques. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.; Choi, W.S.; Jeong, J.O. A Review of Advanced Hydrogel Applications for Tissue Engineering and Drug Delivery Systems as Biomaterials. Gels 2024, 10, 693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Yang, L.; Lv, D.; Sun, R.; Zhang, T.; Li, Y.; Bao, Q.; Zhang, M.; Wang, L.; et al. Towards Intelligent Wound Care: Hydrogel-Based Wearable Monitoring and Therapeutic Platforms. Polymers 2025, 17, 1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maikovych, O.; Pasetto, P.; Nosova, N.; Kudina, O.; Ostapiv, D.; Samaryk, V.; Varvarenko, S. Functional Properties of Gelatin–Alginate Hydrogels for Use in Chronic Wound Healing Applications. Gels 2025, 11, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gounden, V.; Singh, M. Hydrogels and Wound Healing: Current and Future Prospects. Gels 2024, 10, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, W.; Kim, J.; Kim, C.; Chang, H.; Ahn, Y.; Schaffer, D.; Baek, J. Hydrogel fabrication techniques for advanced artificial sensory systems. Int. J. Extrem. Manuf. 2025, 7, 062002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.; Yao, D.; Yang, L. Soft Bimodal Sensor Array Based on Conductive Hydrogel for Driving Status Monitoring. Sensors 2020, 20, 1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, X.; Huang, J.; A, Y.; Yuan, N.; Chen, C.; Lin, D. Research Advances in Mechanical Properties and Applications of Dual Network Hydrogels. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 15757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumon, M.M.H.; Rahman, M.S.; Akib, A.A.; Sohag, M.S.; Rakib, M.R.A.; Khan, M.A.R.; Yesmin, F.; Shakil, M.S.; Khan, M.M.R. Progress in hydrogel toughening: Addressing structural and crosslinking challenges for biomedical applications. Discov. Mater. 2025, 5, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maikovych, O.V.; Nosova, N.G.; Yakoviv, M.V.; Varvarenko, S.M.; Voronov, S.A. Composite materials based on polyacrylamide and gelatin reinforced with polypropylene microfiber. Vopr. Khimii Khimicheskoi Tekhnologii 2021, 1, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Li, J.; Luo, J.; Gao, Q.; Mao, A.; Li, J. Research progress on double-network hydrogels. Mater. Today Commun. 2021, 29, 102757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, H. Double-Network Tough Hydrogels: A Brief Review on Achievements and Challenges. Gels 2022, 8, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Shen, Z.; Wang, H.; Song, Z.; Yu, D.; Li, G.; Liu, X.; Liu, W. Progress in Research on Metal Ion Crosslinking Alginate-Based Gels. Gels 2025, 11, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samaryk, V.; Varvarenko, S.; Nosova, N.; Fihurka, N.; Musyanovych, A.; Landfester, K.; Popadyuk, N.; Voronov, S. Optical properties of hydrogels filled with dispersed nanoparticles. Chem. Chem. Technol. 2017, 11, 449–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suberlyak, O.; Grytsenko, O.; Hischak, K.; Hnatchuk, N. Research of influence the nature of metal on mechanism of synthesis polyvinilpyrrolidone metal copolymers. Chem. Chem. Technol. 2013, 7, 289–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grytsenko, O.; Pukach, P.; Suberlyak, O.; Shakhovska, N.; Karovič, V. Usage of mathematical modeling and optimization in development of hydrogel medical dressings production. Electronics 2021, 10, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanez, F.; Concheiro, A.; Alvarez-Lorenzo, C. Macromolecule release and smoothness of semiinterpenetrating PVP–pHEMA networks for comfortable soft contact lenses. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2008, 69, 1094–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamburini, G.; Canevali, C.; Ferrario, S.; Bianchi, A.; Sansonetti, A.; Simonutti, R. Optimized Semi-Interpenetrated p(HEMA)/PVP Hydrogels for Artistic Surface Cleaning. Materials 2022, 15, 6739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciardelli, G.; Cristallini, C.; Barbani, N.; Benedetti, G.; Crociani, A.; Travison, L.; Giusti, P. Bioartificial polymeric materials: -amylase, poly(2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate), poly(N-vinylpyrrolidone) system. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2002, 203, 1666–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frutos, P.; Diez-Peña, E.; Frutos, G.; Barrales-Rienda, J. Release of gentamicin sulphate from a modified commercial bone cement. Effect of (2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate) comonomer and poly(N-vinyl-2-pyrrolidone) additive on release mechanism and kinetics. Biomaterials 2002, 23, 3787–3797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grytsenko, O.; Dulebova, L.; Spišák, E.; Pukach, P. Metal-filled polyvinylpyrrolidone copolymers: Promising platforms for creating sensors. Polymers 2023, 15, 2259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashtyk, Y.; Fechan, A.; Grytsenko, O.; Hotra, Z.; Kremer, I.; Suberlyak, O.; Aksimentyeva, O.; Horbenko, Y.; Kotsarenko, M. Electrical elements of the optical systems based on hydrogel-electrochromic polymer composites. Mol. Cryst. Liq. Cryst. 2019, 672, 150–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saptaji, K.; Iza, N.R.; Widianingrum, S.; Mulia, V.K.; Setiawan, I. Poly(2-Hydroxyethyl Methacrylate) Hydrogels for Contact Lens Applications—A Review. Makara J. Sci. 2021, 25, 145−154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zare, M.; Bigham, A.; Zare, M.; Luo, H.; Rezvani Ghomi, E.; Ramakrishna, S. pHEMA: An Overview for Biomedical Applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipecka-Szymczyk, K.; Makowska-Janusik, M.; Marczak, W. Molecular Dynamics Simulations of HEMA-Based Hydrogels for Ophthalmological Applications. Molecules 2024, 29, 5784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, E.; Kumar, S.; Lee, J.; Jang, J.; Park, J.H.; Chang, M.C.; Kwon, I.; Lee, J.S.; Huh, Y.I. Modified hydrogels based on poly(2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate) (pHEMA) with higher surface wettability and mechanical properties. Macromol. Res. 2017, 25, 704–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suberlyak, O.; Skorokhoda, V. Hydrogels based on polyvinylpyrrolidone copolymers. In Hydrogels; Haider, S., Haider, A., Eds.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2018; pp. 136–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobczak-Kupiec, A.; Kudłacik-Kramarczyk, S.; Drabczyk, A.; Cylka, K.; Tyliszczak, B. Studies on PVP-based hydrogel polymers as dressing materials with prolonged anticancer drug delivery function. Materials 2023, 16, 2468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suberlyak, O.; Grytsenko, O.; Kochubei, V. The role of FeSO4 in the obtaining of polyvinylpirolidone copolymers. Chem. Chem. Technol. 2015, 9, 429–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grytsenko, O.; Dulebova, L.; Spišák, E.; Berezhnyy, B. New Materials Based on Polyvinylpyrrolidone-Containing Copolymers with Ferromagnetic Fillers. Materials 2022, 15, 5183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grytsenko, O.; Dulebova, L.; Suberlyak, O.; Skorokhoda, V.; Spišák, E.; Gajdos, I. Features of structure and properties of pHEMA-gr-PVP block copolymers, obtained in the presence of Fe2+. Materials 2020, 13, 4580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suberlyak, O.V.; Hrytsenko, O.M.; Hishchak, K.Y. Influence of the metal surface of powder filler om the structure and properties of composite materials based on the co-polymers of methacrylates with polyvinylpyrrolidone. Mater. Sci. 2016, 52, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roca-Arroyo, A.F.; Gutierrez-Rivera, J.A.; Morton, L.D.; Castilla-Casadiego, D.A. Hydrogel Network Architecture Design Space: Impact on Mechanical and Viscoelastic Properties. Gels 2025, 11, 588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, B.; Tang, D.; Wu, X.; Xu, Z.; Gu, J.; Han, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Qin, M.; Zou, X.; Wang, W.; et al. Engineering hydrogels with homogeneous mechanical properties for controlling stem cell lineage specification. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2110961118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, V.A.; Staunton, T.A.; Laaser, J.E. Effect of Cross-Link Homogeneity on the High-Strain Behavior of Elastic Polymer Networks. Macromolecules 2024, 57, 4670–4679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, D.J.; Satar, M.; Al-Hamzawi, A.K.; Shabbani, H.; Mutar, M.A.; Othman, M.R. Photopolymerization of hydrogel using three types of cross-linking agents: Effects of water content, mechanical and thermal properties. S. Afr. J. Chem. Eng. 2025, 53, 400–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, R.O.; Penott-Chang, E.K.; Gáscue, B.R.; Müller, A.J. The effect of the solvent employed in the synthesis of hydrogels of poly (acrylamide-co-methyl methacrylate) on their structure, properties and possible biomedical applications. Eur. Polym. J. 2017, 88, 148–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Halah, A.; González, N.; Contreras, J.; Francisco López-Carrasquero, F. Effect of the synthesis solvent in swelling ability of polyacrylamide hydrogels. J. Polym. Res. 2020, 27, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bühler, V. Polyvinylpyrrolidone Excipients for Pharmaceuticals: Povidone, Crospovidone and Copovidone; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; pp. 1–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes, W.E. Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, 95th ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2014; 2670p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichardt, C.; Welton, T. Solvents and Solvent Effects in Organic Chemistry; Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA: Weinheim, Germany, 2011; p. 718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 3219; Plastics—Polymers/Resins in the Liquid State or as Emulsions or Dispersions—Determination of Viscosity Using a Rotational Viscometer with Defined Shear Rate. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2021.

- Muller, K. Identification and determination of polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) as well as determination of active substances in PVP-containing drug preparations. Pharm. Acta Helv. 1968, 43, 107–122. [Google Scholar]

- Flory, P.J.; Rehner, J. Statistical mechanics of cross-linked polymer networks. J. Chem. Phys. 1943, 11, 521–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D2240-15; Standard Test Method for Rubber Property–Durometer Hardness. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2015.

| № | HEMA | PVP | E, kgf/cm2 | MC, kg/mol | ρ, kg/m3 | μ, mol/m3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 100 | 0 | 5.41 | 12 | 1308 | 54.08 |

| 2 | 90 | 10 | 4.45 | 21 | 1295 | 30.86 |

| 3 | 80 | 20 | 3.65 | 26 | 1288 | 24.77 |

| 4 | 70 | 30 | 3.35 | 28 | 1260 | 22.50 |

| 5 | 60 | 40 | 2.80 | 34 | 1210 | 17.79 |

| 6 | 50 | 50 | 1.50 | 63 | 1135 | 9.00 |

| Solvent | Dynamic Viscosity, mPa⋅s | Polar Index | Solvent Type | Solvation Capacity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H2O | 0.89 | 10.2 | Protic | Strong donor and acceptor of H-bonds. |

| DMSO | 1.99 | 7.2 | Aprotic | Strong H-bond acceptor. Solvates cations and polar molecules. |

| DEG | 35.7 | 7.5 | Protic | Strong donor and acceptor of H-bonds. |

| HOCy | 41.1 | 4.0–5.0 | Protic | Less polar than H2O or DEG. Has a significant nonpolar fragment. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Grytsenko, O.; Pukach, P.; Vovk, M.; Baran, N. Structural Features and Mechanical Properties of Hydrogels Based on PVP Copolymers, Obtained in the Presence of a Solvent. Gels 2025, 11, 1008. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11121008

Grytsenko O, Pukach P, Vovk M, Baran N. Structural Features and Mechanical Properties of Hydrogels Based on PVP Copolymers, Obtained in the Presence of a Solvent. Gels. 2025; 11(12):1008. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11121008

Chicago/Turabian StyleGrytsenko, Oleksandr, Petro Pukach, Myroslava Vovk, and Nataliia Baran. 2025. "Structural Features and Mechanical Properties of Hydrogels Based on PVP Copolymers, Obtained in the Presence of a Solvent" Gels 11, no. 12: 1008. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11121008

APA StyleGrytsenko, O., Pukach, P., Vovk, M., & Baran, N. (2025). Structural Features and Mechanical Properties of Hydrogels Based on PVP Copolymers, Obtained in the Presence of a Solvent. Gels, 11(12), 1008. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11121008