Symbiosis Among Naematelia aurantialba, Stereum hirsutum, and Their Associated Microbiome in the Composition of a Cultivated Mushroom Complex JinEr

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection and Processing Methodology

2.2. DNA Extraction and PCR Amplification

2.3. Microbial Community Diversity Analysis and Functional Prediction

2.4. Isolation and Characterization of Culturable Endomycotic Bacteria

2.5. Antagonistic Assay Between Endomycotic Bacteria and Host

2.6. Statistical Analysis and Visualization

3. Results

3.1. Composition of Bacterial and Fungal Taxa

3.2. Community Diversity of the Endomycotic Microbiome

3.2.1. Bacterial Diversity Within Basidiomata and Substrate Compartments

3.2.2. Community Diversity of Endomycotic Fungi

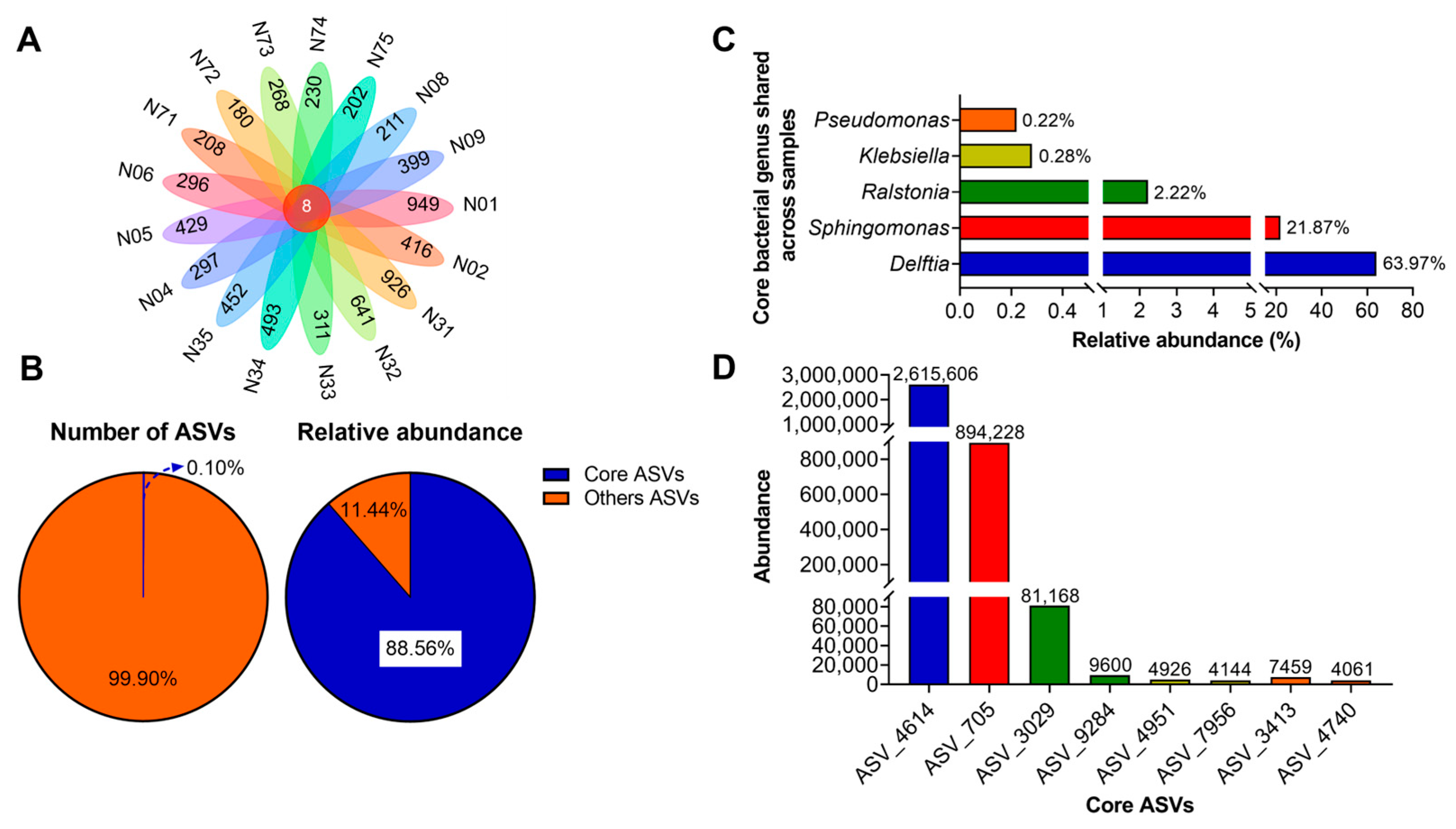

3.3. Core and Keystone Bacteria in the Samples

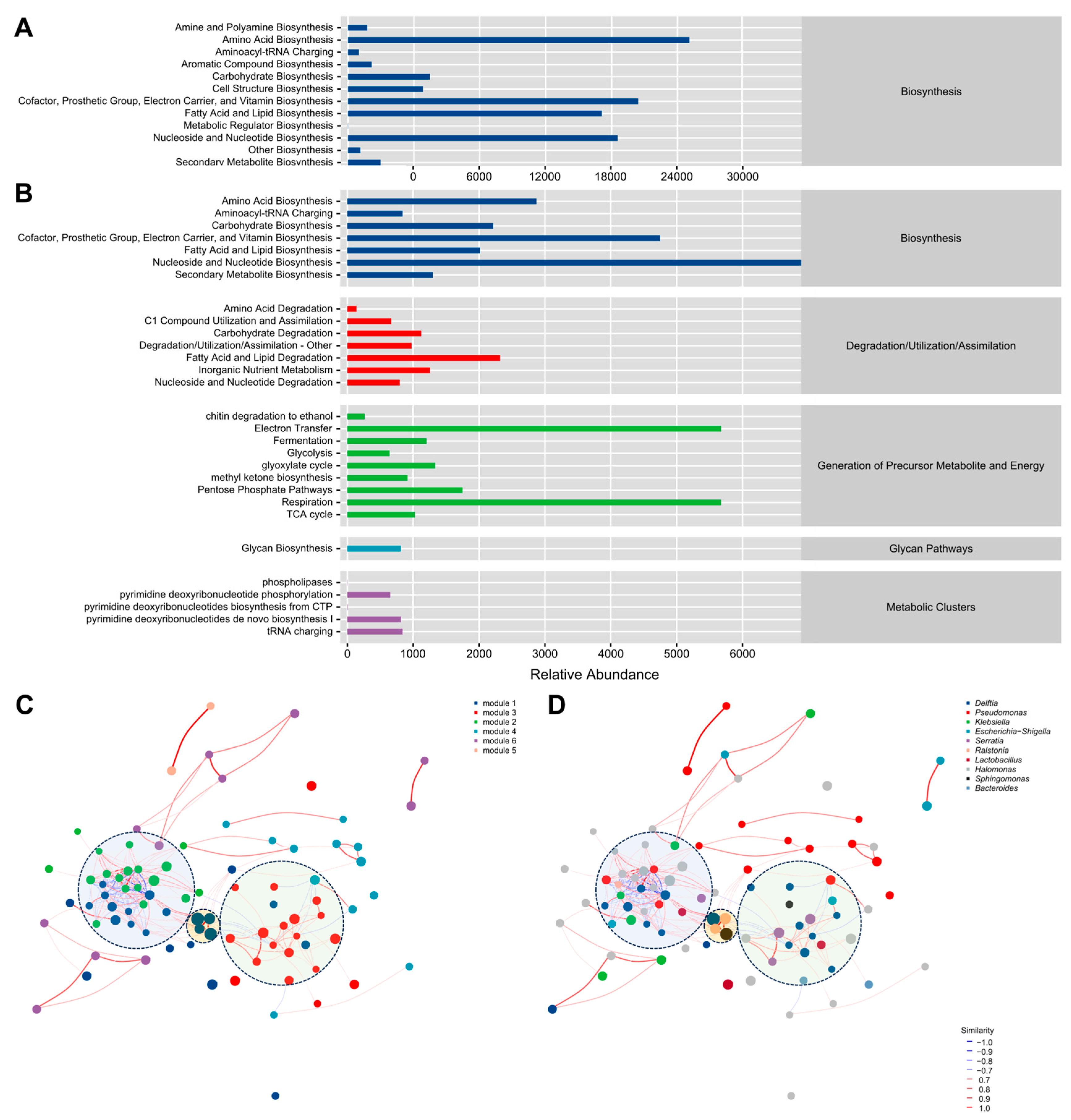

3.4. Functional Analysis of the Endomycotic Microbiome

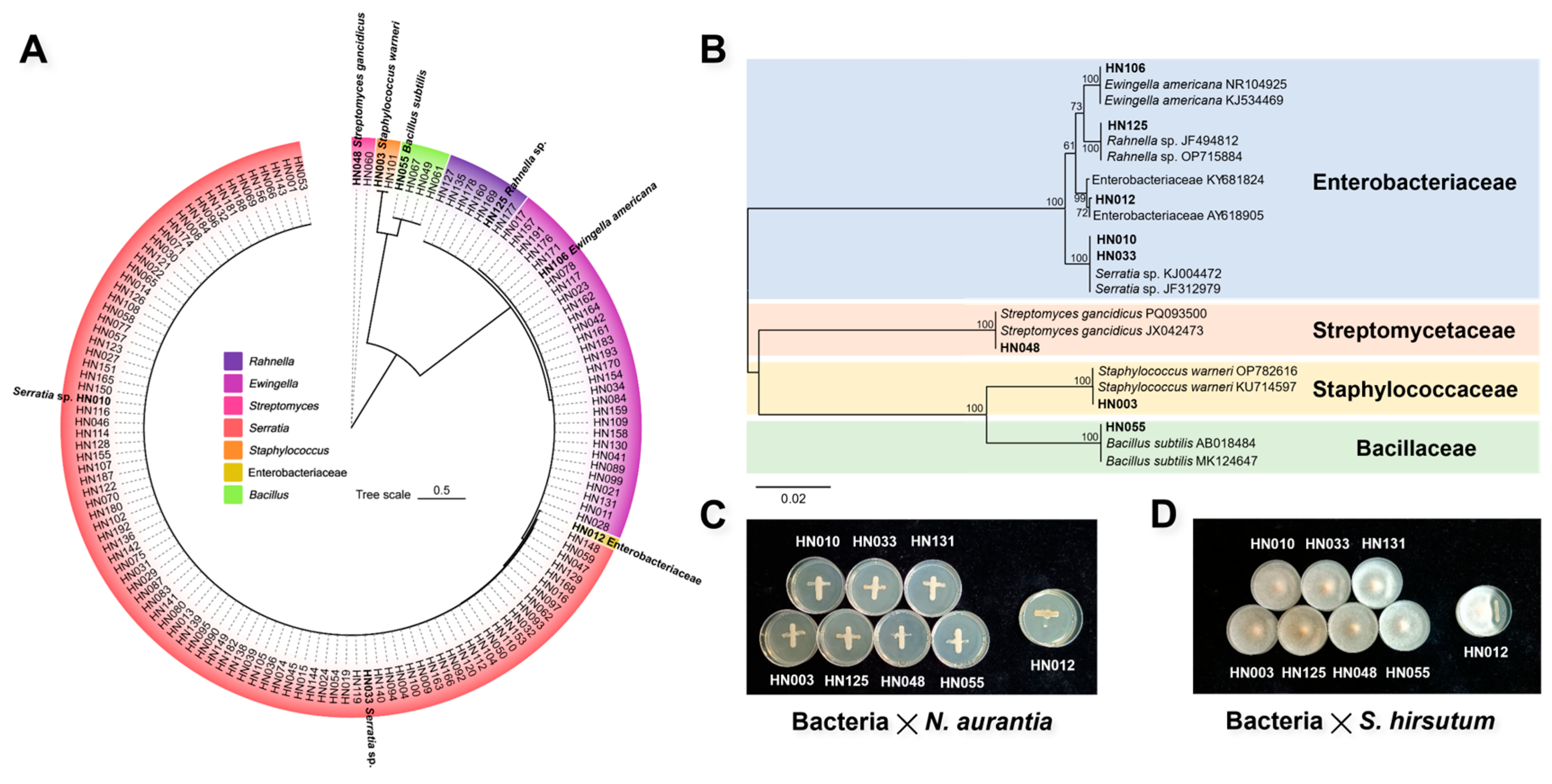

3.5. Isolation and Identification of Culturable Endomycotic Bacteria

4. Discussion

4.1. Potential Origins of Endomycotic Bacteria in JinEr Mushrooms

4.2. Potential Functions of Endomycotic Bacteria in JinEr Mushrooms

4.3. Interaction Among S. hirsutum, N. aurantialba and Associated Microorganisms

4.4. Culturable Endomycotic Bacteria in JinEr Mushrooms

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yang, Y.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Dong, C. First report of bacterial brown rot disease caused by Ewingella americana on cultivated Naematelia aurantialba in China. Plant Dis. 2023, 107, 2513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Wang, M.; Chen, N.; Wang, X.; Fu, C.; Li, Y.; Gan, X.; Lv, P.; Zhang, Y. Isolation, structures, bioactivities, application and future prospective for polysaccharides from Tremella aurantialba: A review. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1091210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Huang, K.; Pu, K.; Li, L.; Jiang, W.; Wu, J.; Kawagishi, H.; Li, M.; Qi, J. Naematelia aurantialba: A comprehensive review of its medicinal, nutritional, and cultivation aspects. Food Med. Homol. 2024, 2, 9420072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Dong, C. Fruiting body heterogeneity, dimorphism and haustorium-like structure of Naematelia aurantialba (Jin Er mushroom). J. Fungi 2024, 10, 557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liddell, C.; Jefferies, P.; Young, T. Interfungal parasitic relationships. Mycologia 1997, 89, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, H.; Yang, K.; Wang, S.; Wang, R.; Li, S.; Lei, P.; Xu, H.; Qiu, Y.; et al. Whole genome sequencing and annotation of Naematelia aurantialba (Basidiomycota, edible-medicinal fungi). J. Fungi 2021, 8, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.J. Morphological and molecular studies in the genus Tremella. Bibl. Mycol. 1998, 174, 1–225. [Google Scholar]

- Schoutteten, N.; Begerow, D.; Verbeken, M. Mycoparasitism in Basidiomycota. Authorea 2024, Preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deveau, A.; Bonito, G.; Uehling, J.; Paoletti, M.; Becker, M.; Bindschedler, S.; Hacquard, S.; Herve, V.; Labbe, J.; Lastovetsky, O.A.; et al. Bacterial-fungal interactions: Ecology, mechanisms and challenges. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2018, 42, 335–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, A.J.; House, G.L.; Morales, D.P.; Kelliher, J.M.; Gallegos-Graves, L.V.; LeBrun, E.S.; Davenport, K.W.; Palmieri, F.; Lohberger, A.; Bregnard, D.; et al. Widespread bacterial diversity within the bacteriome of fungi. Commun. Biol. 2021, 4, 1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braat, N.; Koster, M.C.; Wösten, H.A.B. Beneficial interactions between bacteria and edible mushrooms. Fungal Biol. Rev. 2022, 39, 60–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasco, J.; Preston, G.M. Growing edible mushrooms: A conversation between bacteria and fungi. Environ. Microbiol. 2019, 22, 858–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gohar, D.; Pent, M.; Põldmaa, K.; Bahram, M. Bacterial community dynamics across developmental stages of fungal fruiting bodies. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2020, 96, fiaa175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Splivallo, R.; Deveau, A.; Valdez, N.; Kirchhoff, N.; Frey-Klett, P.; Karlovsky, P. Bacteria associated with truffle-fruiting bodies contribute to truffle aroma. Environ. Microbiol. 2014, 17, 2647–2660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napitupulu, T.P. Agricultural relevance of fungal mycelial growth-promoting bacteria: Mutual interaction and application. Microbiol. Res. 2025, 290, 127978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aslani, M.A.; Harighi, B.; Abdollahzadeh, J. Screening of endofungal bacteria isolated from wild growing mushrooms as potential biological control agents against brown blotch and internal stipe necrosis diseases of Agaricus bisporus. Biol. Control 2018, 119, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazir, R.; Zhang, M.; de Boer, W.; van Elsas, J.D. The capacity to comigrate with Lyophyllum sp. strain Karsten through different soils is spread among several phylogenetic groups within the genus Burkholderia. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2012, 50, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pent, M.; Põldmaa, K.; Bahram, M. Bacterial communities in boreal forest mushrooms are shaped both by soil parameters and host identity. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Chen, X.; Shi, X.; Yang, Z.; Yang, L.; Liu, D.; Yu, F. Endophytic bacterial community, core taxa, and functional variations within the fruiting bodies of Laccaria. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, B.; Liu, D.; Bai, H.; Jin, L.; Wang, B.; Ruan, H.; Mao, L.; Jin, F.; et al. Effects of nitrogen addition on rhizospheric soil microbial communities of poplar plantations at different ages. For. Ecol. Manag. 2021, 494, 119328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGee, C.F.; Byrne, H.; Irvine, A.; Wilson, J. Diversity and dynamics of the DNA- and cDNA-derived compost fungal communities throughout the commercial cultivation process for Agaricus bisporus. Mycologia 2017, 109, 475–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, T.; Wen, D.; Bates, C.T.; Wu, L.; Guo, X.; Liu, S.; Su, Y.; Lei, J.; Zhou, J.; Yang, Y. Nutrient supply controls the linkage between species abundance and ecological interactions in marine bacterial communities. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Dou, Y.; Wang, B.; Xue, Z.; Wang, Y.; An, S.; Chang, S.X. Deciphering factors driving soil microbial life-history strategies in restored grasslands. Imeta 2023, 2, e66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, D.; He, X.; Chater, C.C.C.; Perez-Moreno, J.; Yu, F. Microbiome community structure and functional gene partitioning in different micro-niches within a sporocarp-forming fungus. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 629352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nilsson, R.H.; Larsson, K.-H.; Taylor, A.F.S.; Bengtsson-Palme, J.; Jeppesen, T.S.; Schigel, D.; Kennedy, P.; Picard, K.; Glöckner, F.O.; Tedersoo, L.; et al. The UNITE database for molecular identification of fungi: Handling dark taxa and parallel taxonomic classifications. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, D259–D264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, E.H. Measurement of diversity. Nature 1949, 163, 688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, C.E. A mathematical theory of communication. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 1948, 27, 379–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olesen, J.M.; Bascompte, J.; Dupont, Y.L.; Jordano, P. The modularity of pollination networks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 19891–19896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Perez-Moreno, J.; He, X.; Garibay-Orijel, R.; Yu, F. Truffle microbiome is driven by fruit body compartmentalization rather than soils conditioned by different host trees. mSphere 2021, 6, e0003921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, J.; Zhang, Y.; Cai, Y.; Shi, X.; Zhang, K.; Huang, J.; Yang, C.; He, X.; Yu, F.; Liu, W. Spatial ratio of two fungal genotypes content of Naematelia aurantialba and Stereum hirsutum in nutritional growth substrate and fruiting bodies reveals their potential parasitic life cycle characteristics. J. Agric. Food. Res. 2025, 22, 102101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoyo, G. How plants recruit their microbiome? New insights into beneficial interactions. J. Adv. Res. 2022, 40, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Li, J.; Carvalhais, L.C.; Percy, C.D.; Prakash Verma, J.; Schenk, P.M.; Singh, B.K. Evidence for the plant recruitment of beneficial microbes to suppress soil-borne pathogens. New Phytol. 2020, 229, 2873–2885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosse, B. Honey-coloured, sessile Endogone spores: II. Changes in fine structure during spore development. Archiv. Mikrobiol. 1970, 74, 129–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohshima, S.; Sato, Y.; Fujimura, R.; Takashima, Y.; Hamada, M.; Nishizawa, T.; Narisawa, K.; Ohta, H. Mycoavidus cysteinexigens gen. nov., sp. nov., an endohyphal bacterium isolated from a soil isolate of the fungus Mortierella elongata. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2016, 66, 2052–2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, H.; Glaeser, S.P.; Alabid, I.; Imani, J.; Haghighi, H.; Kampfer, P.; Kogel, K.H. The abundance of endofungal bacterium Rhizobium radiobacter (syn. Agrobacterium tumefaciens) increases in its fungal host Piriformospora indica during the tripartite sebacinalean symbiosis with higher plants. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desirò, A.; Hao, Z.; Liber, J.A.; Benucci, G.M.N.; Lowry, D.; Roberson, R.; Bonito, G. Mycoplasma-related endobacteria within Mortierellomycotina fungi: Diversity, distribution and functional insights into their lifestyle. ISME J. 2018, 12, 1743–1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnolucci, M.; Battini, F.; Cristani, C.; Giovannetti, M. Diverse bacterial communities are recruited on spores of different arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal isolates. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2015, 51, 379–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desirò, A.; Naumann, M.; Epis, S.; Novero, M.; Bandi, C.; Genre, A.; Bonfante, P. Mollicutes-related endobacteria thrive inside liverwort-associated arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 15, 822–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrada-de los Santos, P.; Palmer, M.; Chávez-Ramírez, B.; Beukes, C.; Steenkamp, E.T.; Briscoe, L.; Khan, N.; Maluk, M.; Lafos, M.; Humm, E.; et al. Whole genome analyses suggests that Burkholderia sensu lato contains two additional novel genera (Mycetohabitans gen. nov., and Trinickia gen. nov.): Implications for the evolution of diazotrophy and nodulation in the Burkholderiaceae. Genes 2018, 9, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaffer, J.P.; U’Ren, J.M.; Gallery, R.E.; Baltrus, D.A.; Arnold, A.E. An endohyphal bacterium (Chitinophaga, Bacteroidetes) alters carbon source use by Fusarium keratoplasticum (F. solani species complex, Nectriaceae). Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, A.; Fegan, M.; Hayward, C.; Chakraborty, S.; Sly, L.I. Phylogenetic relationships among members of the Comamonadaceae, and description of Delftia acidovorans (den Dooren de Jong 1926 and Tamaoka et al. 1987) gen. nov., comb. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 1999, 49, 567–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, J.; Sun, L.; Dong, X.; Cai, Z.; Sun, X.; Yang, H.; Wang, Y.; Song, W. Characterization of a novel plant growth-promoting bacteria strain Delftia tsuruhatensis HR4 both as a diazotroph and a potential biocontrol agent against various plant pathogens. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 2005, 28, 66–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garavaglia, L.; Cerdeira, S.B.; Vullo, D.L. Chromium (VI) biotransformation by β- and γ-Proteobacteria from natural polluted environments: A combined biological and chemical treatment for industrial wastes. J. Hazard. Mater. 2010, 175, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, S.; Wei, Z.; Shao, Z.; Friman, V.-P.; Cao, K.; Yang, T.; Kramer, J.; Wang, X.; Li, M.; Mei, X.; et al. Competition for iron drives phytopathogen control by natural rhizosphere microbiomes. Nat. Microbiol. 2020, 5, 1002–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavitha, P.; Ganesamoorthy, R.; Kasthuri, K.; Kalikkot, A.P.; Thirugnanasambandham, K.; Yazeedah; Gomathi, R.; Maruthavanan, T. Studies on production of proteins from Delftia MW172212 bacteria and their antibacterial and anticancer applications. J. Pure Appl. Microbiol. 2025, 19, 2322–2332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejman-Yarden, N.; Robinson, A.; Davidov, Y.; Shulman, A.; Varvak, A.; Reyes, F.; Rahav, G.; Nissan, I. Delftibactin-A, a non-ribosomal peptide with broad antimicrobial activity. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 2377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, D.; Chen, X.; Xu, M. Characteristics and functional analysis of the secondary chromosome and plasmids in sphingomonad. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2022, 171, 105402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanholme, R.; Demedts, B.; Morreel, K.; Ralph, J.; Boerjan, W. Lignin biosynthesis and structure. Plant Physiol. 2010, 153, 895–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, C.L.; Andrewes, A.G.; McQuade, T.J.; Starr, M.P.J.C.M. The pigment of Pseudomonas paucimobilis is a carotenoid (Nostoxanthin), rather than a brominated aryl-polyene (xanthomonadin). Curr. Microbiol. 1979, 3, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, C.; Cabral, J.M.S.; van Keulen, F. Isolation of a β-carotene over-producing soil bacterium, Sphingomonas sp. Biotechnol. Lett. 2004, 26, 257–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.; Zhou, Y.; Li, X.; Zhu, F.; Cheng, Y.; Liu, Y.; Deng, Z.; Liu, T. Genome mining of astaxanthin biosynthetic genes from Sphingomonas sp. ATCC 55669 for heterologous overproduction in Escherichia coli. Biotechnol. J. 2015, 11, 228–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asaf, S.; Numan, M.; Khan, A.L.; Al-Harrasi, A. Sphingomonas: From diversity and genomics to functional role in environmental remediation and plant growth. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2020, 40, 138–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.-J.; Park, J.Y.; Balusamy, S.R.; Huo, Y.; Nong, L.K.; Thi Le, H.; Yang, D.C.; Kim, D. Comprehensive genome analysis on the novel species Sphingomonas panacis DCY99T reveals insights into iron tolerance of ginseng. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eguchi, M.; Nishikawa, T.; Macdonald, K.; Cavicchioli, R.; Gottschal, J.C.; Kjelleberg, S. Responses to stress and nutrient availability by the marine ultramicrobacterium Sphingomonas sp. strain RB2256. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1996, 62, 1287–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Kawamura, Y.; Fujiwara, N.; Naka, T.; Liu, H.; Huang, X.; Kobayashi, K.; Ezaki, T. Sphingomonas yabuuchiae sp. nov. and Brevundimonas nasdae sp. nov., isolated from the Russian space laboratory Mir. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2004, 54, 819–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, M.D.; Neufeld, J.D. Ecology and exploration of the rare biosphere. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2015, 13, 217–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Perez-Moreno, J.; Zhang, P.; Wang, R.; Chater, C.C.C.; Yu, F. Distinct compartmentalization of microbial community and potential metabolic function in the fruiting body of Tricholoma matsutake. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, P.; Moran, N.A. The gut microbiota of insects—Diversity in structure and function. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2013, 37, 699–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldroyd, G.E. Speak, friend, and enter: Signalling systems that promote beneficial symbiotic associations in plants. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2013, 11, 252–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey-Klett, P.; Burlinson, P.; Deveau, A.; Barret, M.; Tarkka, M.; Sarniguet, A. Bacterial-fungal interactions: Hyphens between agricultural, clinical, environmental, and food microbiologists. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2011, 75, 583–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.; Schlaeppi, K.; van der Heijden, M.G.A. Keystone taxa as drivers of microbiome structure and functioning. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2018, 16, 567–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Wang, R.; Sun, D.; Li, S.; Xu, H.; Qiu, Y.; Lei, P.; Sun, L.; Xu, X.; Zhu, Y. High-efficiency production of Tremella aurantialba polysaccharide through basidiospore fermentation. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 318, 124268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, S.; Zhao, Y.; Peng, Y.; Shi, Y.; Xie, X.; Chai, A.; Li, B.; Li, L. Comparative genomics assisted functional characterization of Rahnella aceris ZF458 as a novel plant growth promoting rhizobacterium. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 850084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulkova, I.; Wróbel, B.; Dobrzyński, J. Serratia spp. as plant growth-promoting bacteria alleviating salinity, drought, and nutrient imbalance stresses. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1342331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, X.; Aborisade, M.A.; Wang, H.; He, P.; Lu, S.; Cui, N.; Wang, S.; Zhang, H.; Ding, H.; Liu, K. Effect of lignin and plant growth-promoting bacteria (Staphylococcus pasteuri) on microbe-plant Co-remediation: A PAHs-DDTs co-contaminated agricultural greenhouse study. Chemosphere 2020, 256, 127079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hover, T.; Maya, T.; Ron, S.; Sandovsky, H.; Shadkchan, Y.; Kijner, N.; Mitiagin, Y.; Fichtman, B.; Harel, A.; Shanks, R.M.; et al. Mechanisms of bacterial (Serratia marcescens) attachment to, migration along, and killing of fungal hyphae. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2016, 82, 2585–2594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendez-Santiago, E.W.; Gomez-Rodriguez, O.; Sanchez-Cruz, R.; Folch-Mallol, J.L.; Hernandez-Velazquez, V.M.; Villar-Luna, E.; Aguilar-Marcelino, L.; Wong-Villarreal, A. Serratia sp., an endophyte of Mimosa pudica nodules with nematicidal, antifungal activity and growth-promoting characteristics. Arch. Microbiol. 2021, 203, 549–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, W.; Wang, W.; Zuo, S.; Wu, X. Genome sequencing of Rahnella victoriana JZ-GX1 provides new insights into molecular and genetic mechanisms of plant growth promotion. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 828990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmieri, D.; Vitale, S.; Lima, G.; Di Pietro, A.; Turrà, D. A bacterial endophyte exploits chemotropism of a fungal pathogen for plant colonization. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šantrić, L.; Potočnik, I.; Radivojević, L.; Umiljendić, J.G.; Rekanović, E.; Duduk, B.; Milijašević-Marčić, S. Impact of a native Streptomyces flavovirens from mushroom compost on green mold control and yield of Agaricus bisporus. J. Environ. Sci. Health B 2018, 53, 677–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, N. Antimicrobial activity of Streptomyces species against mushroom blotch disease pathogen. J. Basic Microbiol. 2005, 45, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büchner, R.; Vörös, M.; Allaga, H.; Varga, A.; Bartal, A.; Szekeres, A.; Varga, S.; Bajzát, J.; Bakos-Barczi, N.; Misz, A.; et al. Selection and characterization of a Bacillus strain for potential application in industrial production of white button mushroom (Agaricus bisporus). Agronomy 2022, 12, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanojević, O.; Berić, T.; Potočnik, I.; Rekanović, E.; Stanković, S.; Milijašević-Marčić, S. Biological control of green mould and dry bubble diseases of cultivated mushroom (Agaricus bisporus L.) by Bacillus spp. Crop Prot. 2019, 126, 104944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamidizade, M.; Taghavi, S.M.; Moallem, M.; Aeini, M.; Fazliarab, A.; Abachi, H.; Herschlag, R.A.; Hockett, K.L.; Bull, C.T.; Osdaghi, E. Ewingella americana: An emerging multifaceted pathogen of edible mushrooms. Phytopathology 2023, 113, 150–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes, J.E.; Venturini, M.a.E.; Oria, R.; Blanco, D. Prevalence of Ewingella americana in retail fresh cultivated mushrooms (Agaricus bisporus, Lentinula edodes and Pleurotus ostreatus) in Zaragoza (Spain). FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2004, 47, 291–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhang, K.; Cai, Y.; Shi, X.; Yan, Z.; Huang, Q.; Perez-Moreno, J.; Liu, D.; Yang, Z.; Yang, C.; Yu, F.; et al. Symbiosis Among Naematelia aurantialba, Stereum hirsutum, and Their Associated Microbiome in the Composition of a Cultivated Mushroom Complex JinEr. J. Fungi 2026, 12, 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof12010041

Zhang K, Cai Y, Shi X, Yan Z, Huang Q, Perez-Moreno J, Liu D, Yang Z, Yang C, Yu F, et al. Symbiosis Among Naematelia aurantialba, Stereum hirsutum, and Their Associated Microbiome in the Composition of a Cultivated Mushroom Complex JinEr. Journal of Fungi. 2026; 12(1):41. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof12010041

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Kaixuan, Yingli Cai, Xiaofei Shi, Zhuyue Yan, Qiuchen Huang, Jesus Perez-Moreno, Dong Liu, Zhenyan Yang, Chengmo Yang, Fuqiang Yu, and et al. 2026. "Symbiosis Among Naematelia aurantialba, Stereum hirsutum, and Their Associated Microbiome in the Composition of a Cultivated Mushroom Complex JinEr" Journal of Fungi 12, no. 1: 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof12010041

APA StyleZhang, K., Cai, Y., Shi, X., Yan, Z., Huang, Q., Perez-Moreno, J., Liu, D., Yang, Z., Yang, C., Yu, F., & Liu, W. (2026). Symbiosis Among Naematelia aurantialba, Stereum hirsutum, and Their Associated Microbiome in the Composition of a Cultivated Mushroom Complex JinEr. Journal of Fungi, 12(1), 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof12010041