Genetic–Geographic–Chemical Framework of Polyporus umbellatus Reveals Lineage-Specific Chemotypes for Elite Medicinal Line Breeding

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sampling and Genomic DNA Extraction

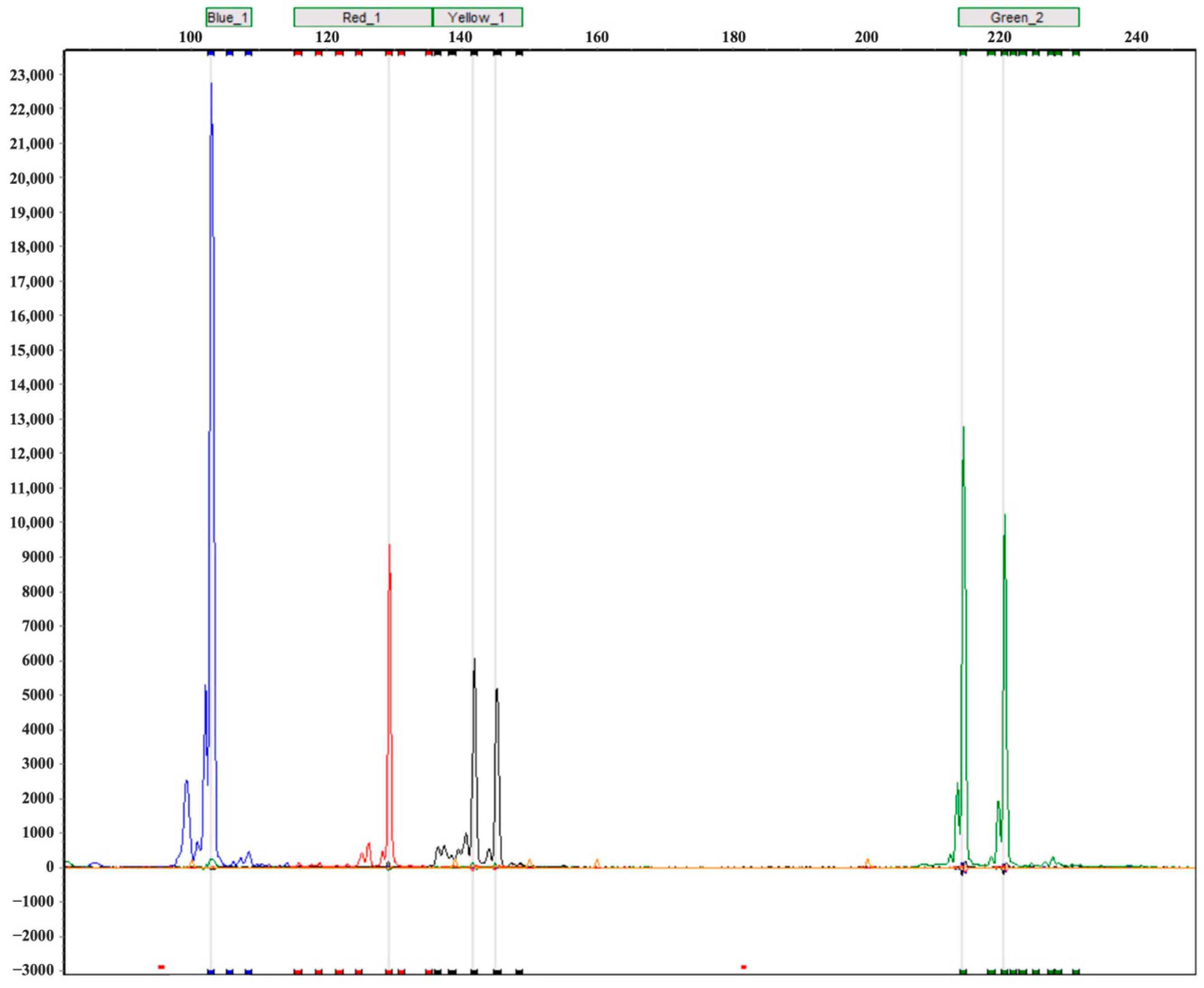

2.2. Genomic SSR Mining and Marker Development

2.3. SSR Genotyping and Diversity Analysis

2.4. SNP Identification and Population Genetic Structure Analysis

2.5. Phylogenetic Study of Chinese P. umbellatus Populations

2.6. Determination of P. umbellatus polysaccharide and Three Steroids

3. Results

3.1. Genomic SSR Characterization and Marker Screening

3.2. Genomic SNP Sequencing and Variant Identification

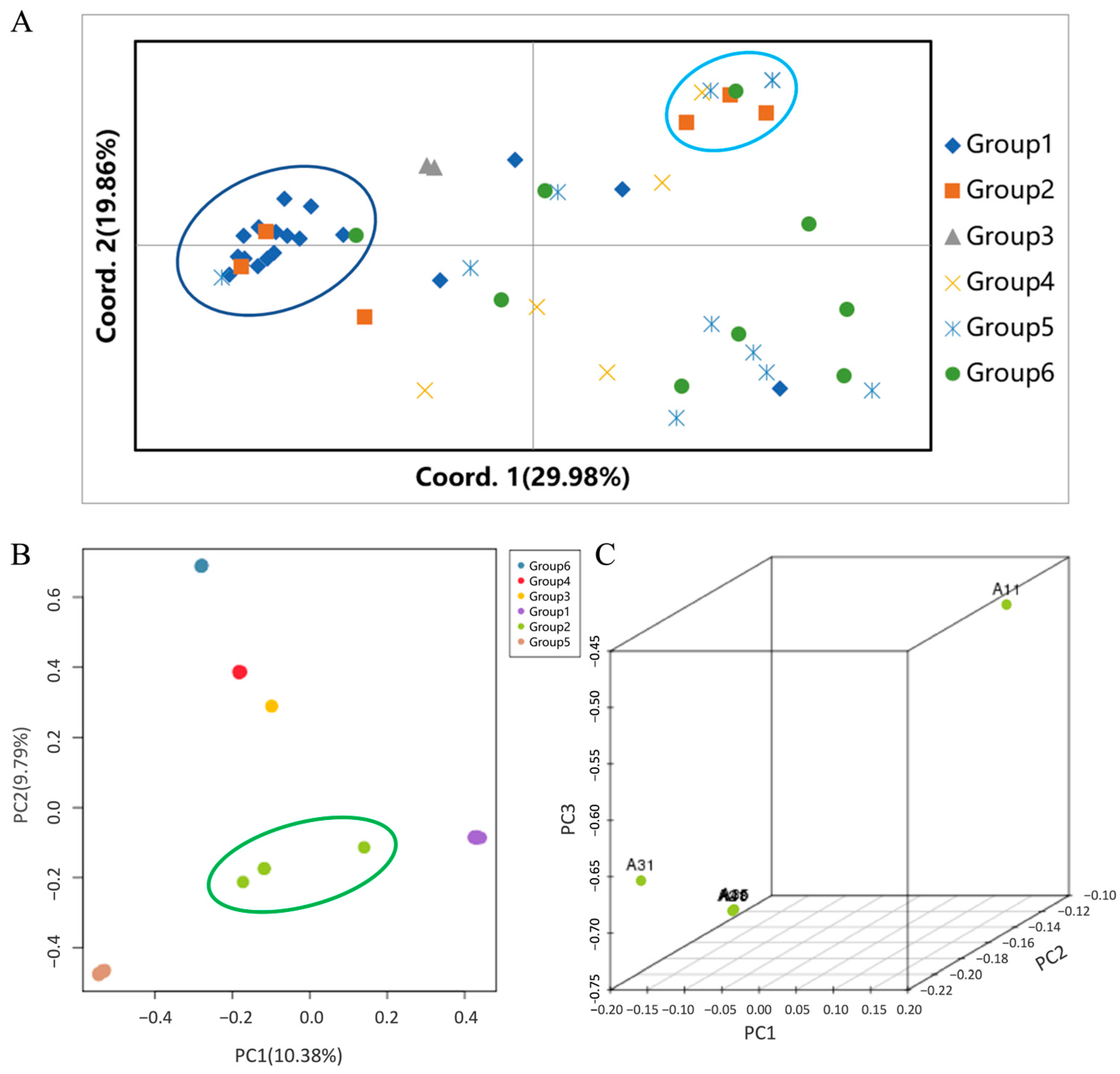

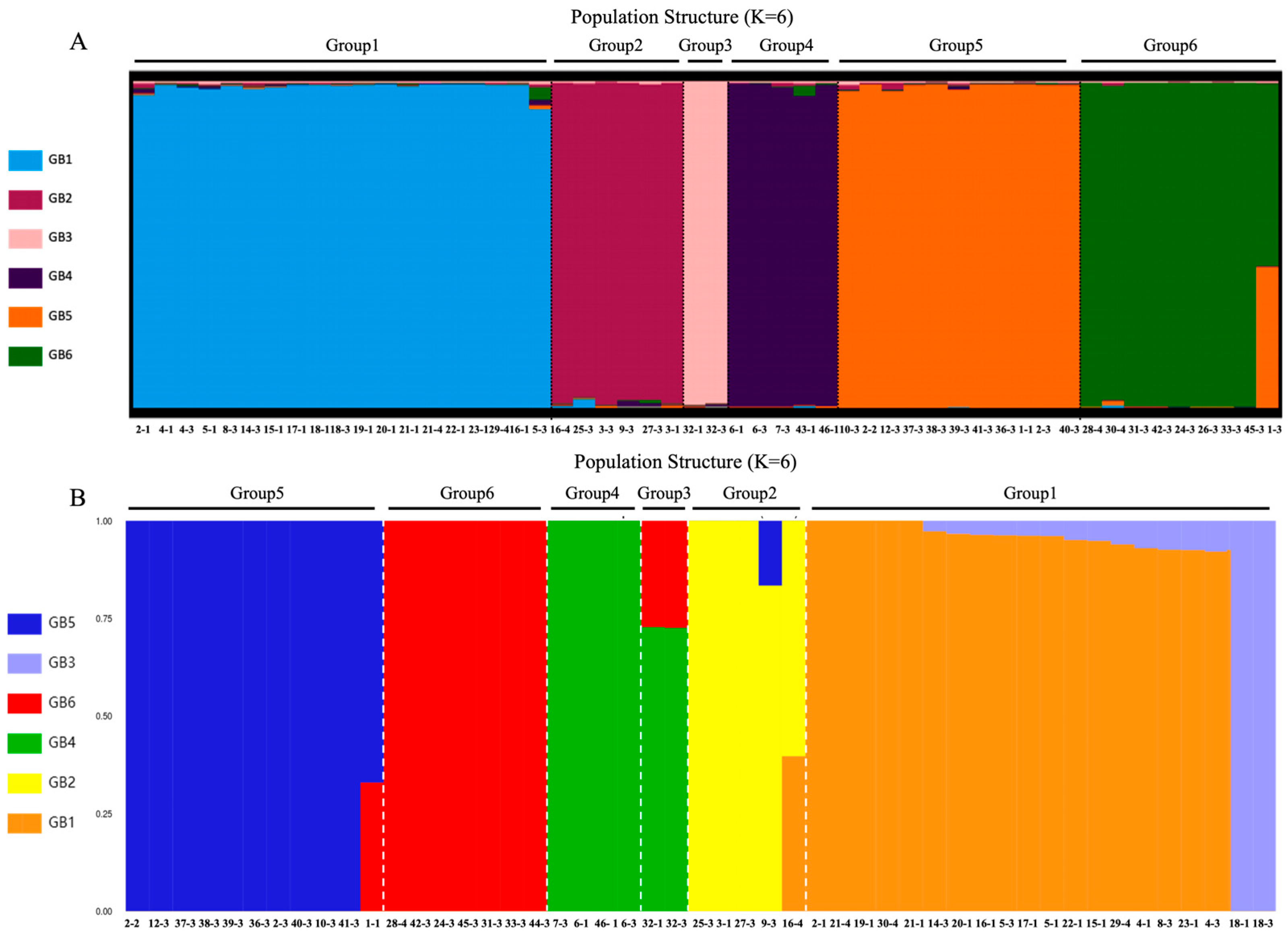

3.3. Population Clustering and Structural Congruence

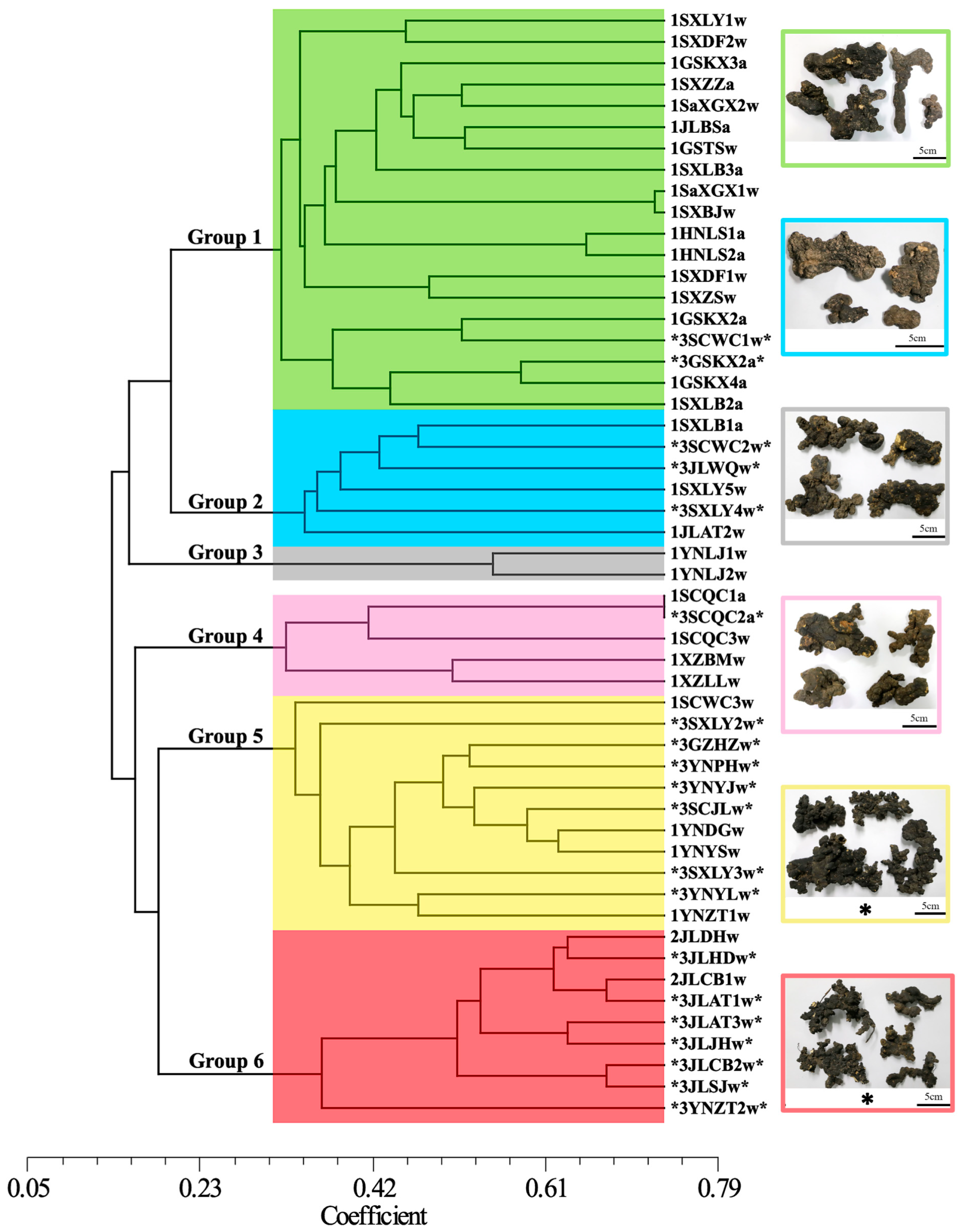

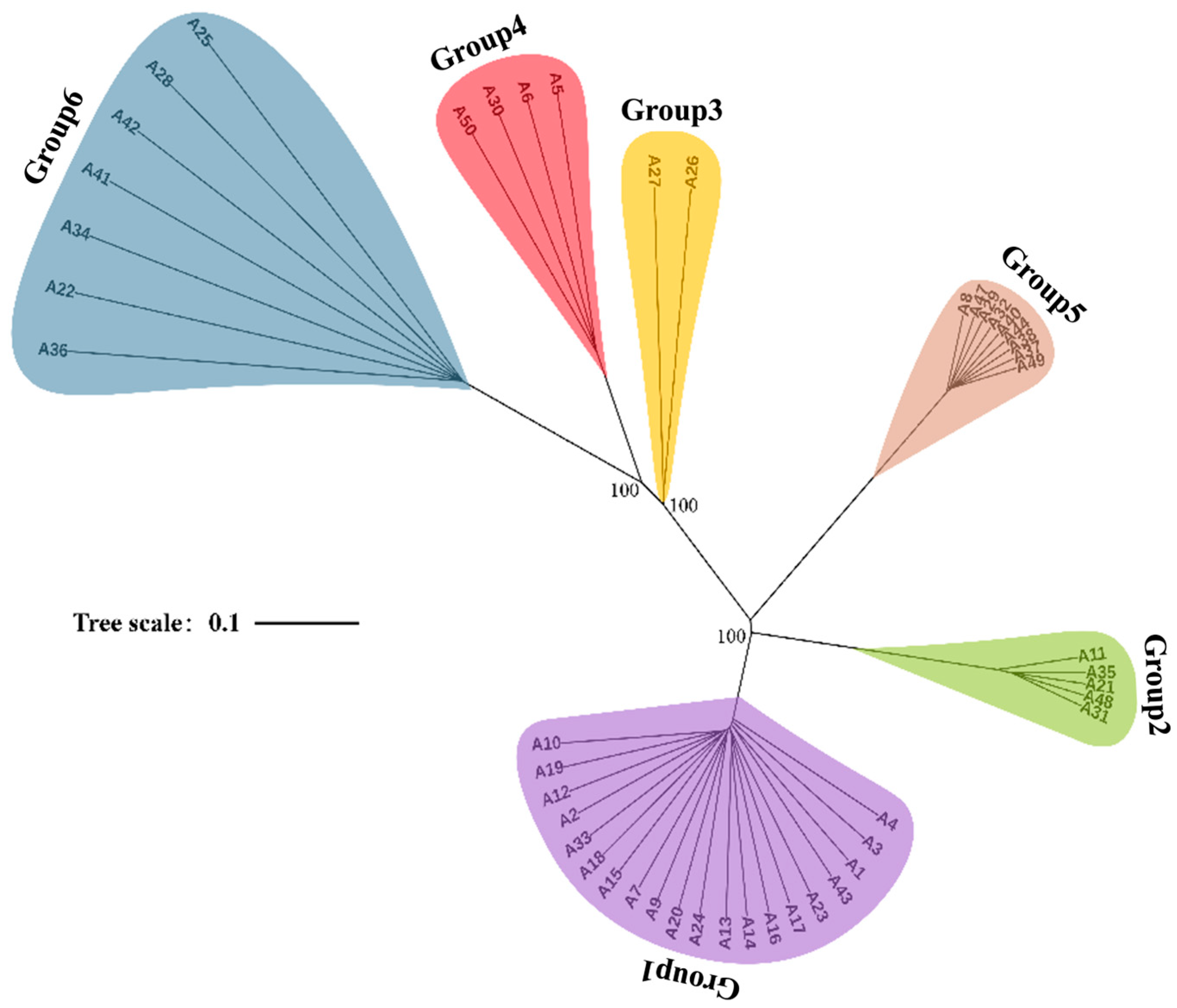

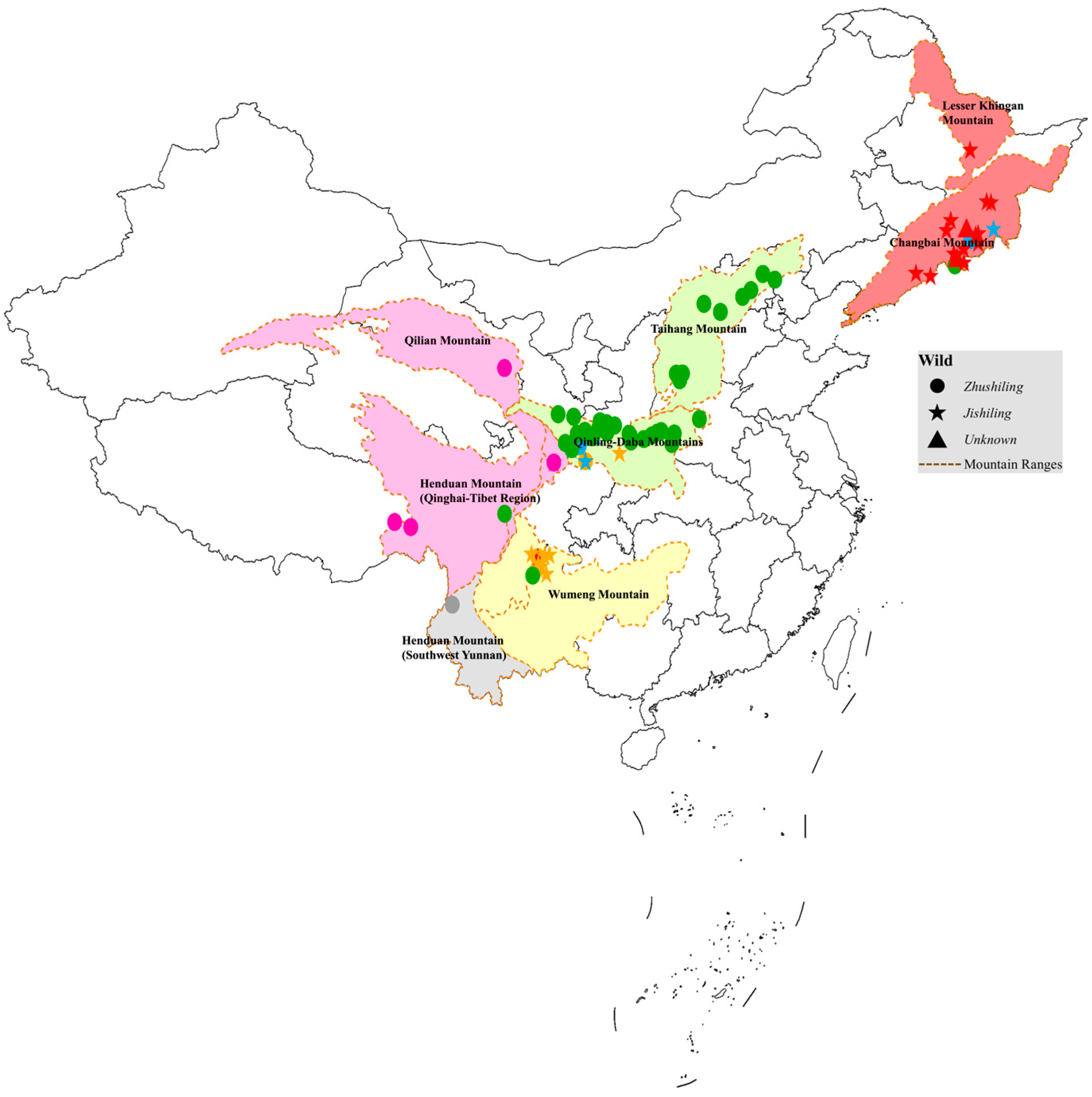

3.4. Characterization of Six Genetic Lineages

3.5. Genetic Diversity Analysis

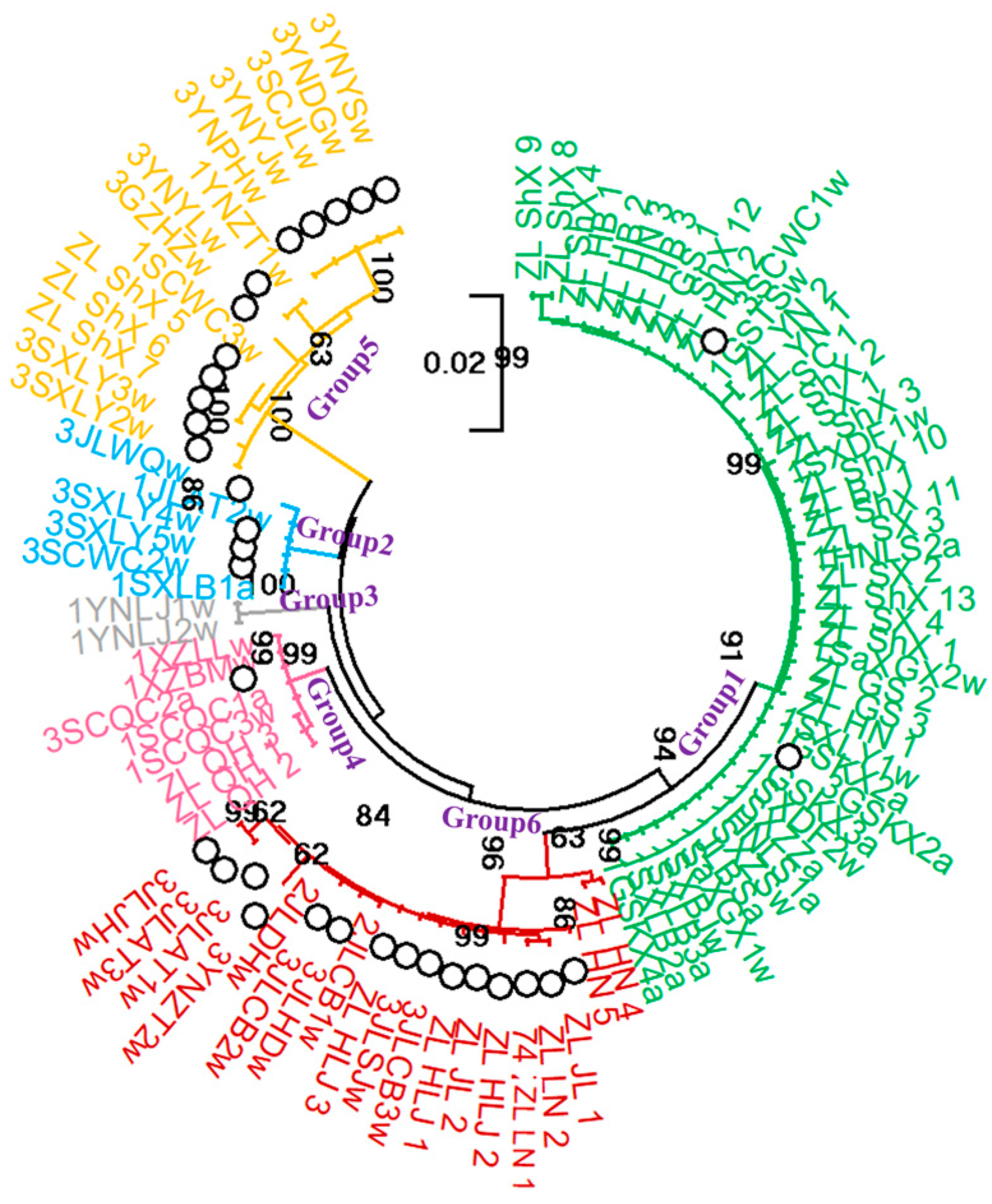

3.6. Phylogenetic Study of Chinese P. umbellatus Populations

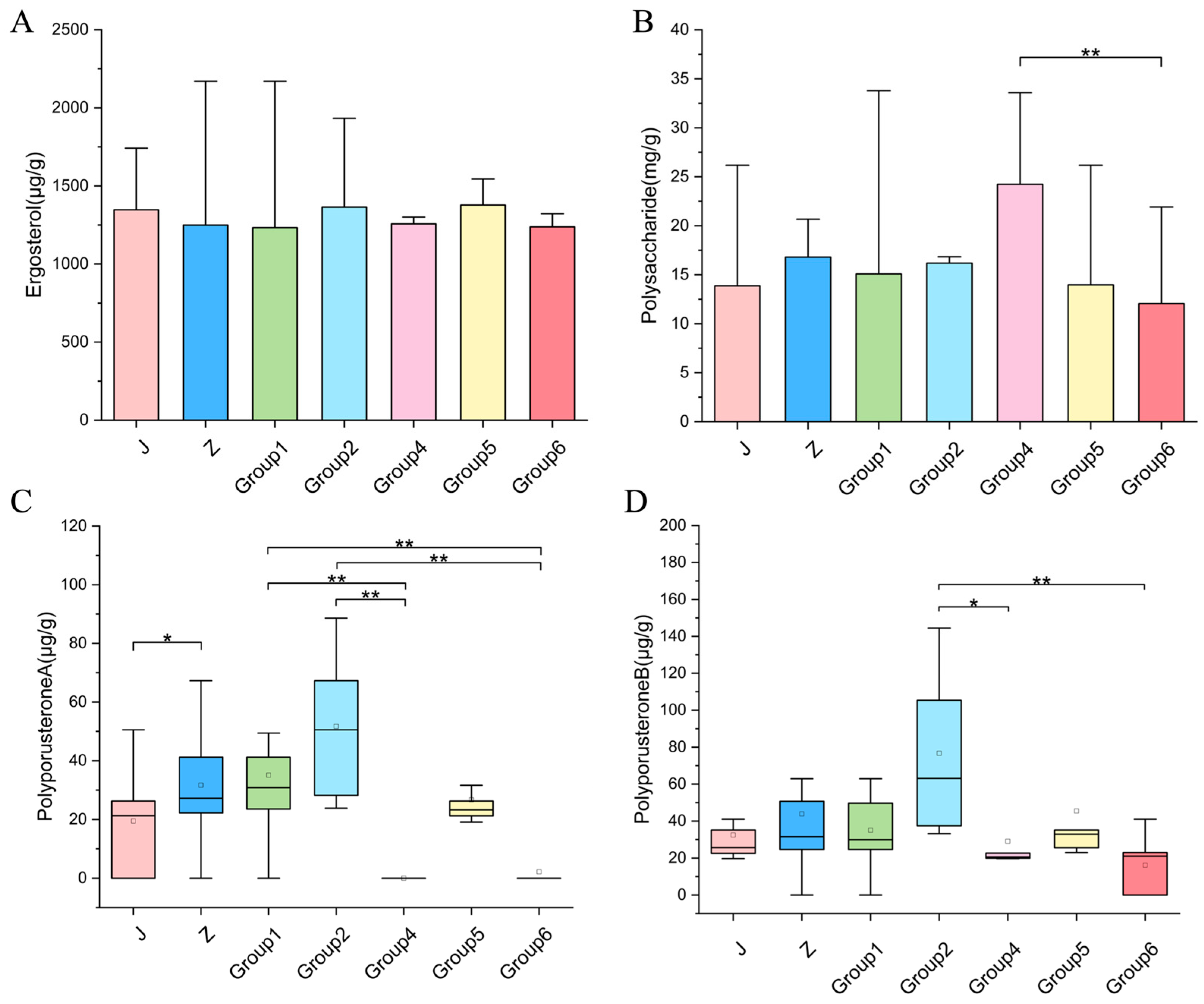

3.7. Quantitative Analysis and Variation in Target Components

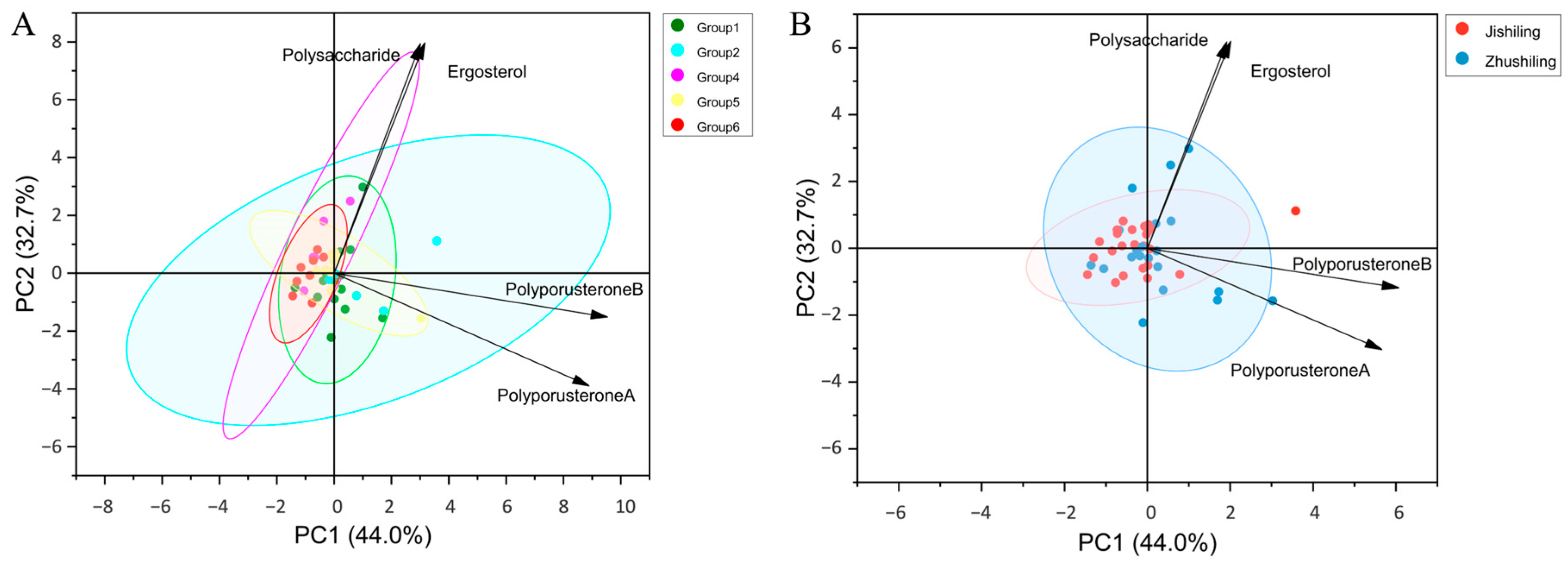

3.8. Multivariate Analysis Identifies Genetic Lineage as the Main Factor Influencing Component Variation

4. Discussion

4.1. High-Resolution Genetic Structure and the Putative Diversity Center of P. umbellatus

4.2. Validation of Six P. umbellatus Clades Through Extensive Sampling

4.3. Geographic Isolation Drives Genetic Divergence and Morphotype Differentiation

4.4. Genotype–Chemotype Coupling: Lineage-Specific Genetic Potential Amid Environmental Plasticity

4.5. Limited Predictive Value of Sclerotium Morphology and Future Perspectives

4.6. Genetic Erosion and Conservation Strategy: Balancing Inbreeding and Clonal Propagation

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AMOVA | Analysis of Molecular Variance |

| CTAB | Cetyl trimethylammonium bromide |

| df | Degrees of Freedom |

| Est. Var. | Estimated Variance |

| HCA | Hierarchical Clustering Analysis |

| He | Expected Heterozygosity |

| Ho | Observed Heterozygosity |

| HPLC | High-Performance Liquid Chromatography |

| I | Shannon’s Information Index |

| ITS | Internal Transcribed Spacers |

| K2P | Kimura 2-parameter |

| LSU | Large Subunit |

| MCMC | Markov chain Monte Carlo |

| ML | Maximum Likelihood |

| MS | Mean Square |

| Na | No. of Observed Allele |

| Ne | No. of Effective Alleles |

| PAGE | Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis |

| PCA | Principal Coordinates Analysis |

| PIC | Polymorphic Information Content |

| Indel | Insertion and Deletion |

| SNP | Single Nucleotide Polymorphism |

| SS | Sum of Squares |

| SSR | Simple Sequence Repeat |

| UPGMA | Unweighted Pair Group Method with Arithmetic Mean |

References

- Gao, W.; Xu, Y.B.; Chen, W.H.; Wu, J.J.; He, Y. A Systematic Review of Advances in Preparation, Structures, Bioactivities, Structural-Property Relationships, and Applications of Polyporus umbellatus Polysaccharides. Food Chem. X 2025, 25, 102161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.J.; Liu, Y.Y.; Liu, L.; Li, B.; Guo, S.X. Genome Sequencing Providing Molecular Evidence of Tetrapolar Mating System and Heterothallic Life Cycle for Edible and Medicinal Mushroom Polyporus umbellatus Fr. J. Fungi 2025, 11, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, D.; Ren, Y.F.; Hua, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, B.; Dong, J.; Efferth, T.; Ma, P.D. Phytochemistry and Bioactivities of the Main Constituents of Polyporus umbellatus (Pers.) Fries. Phytomedicine 2022, 103, 154196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chinese Pharmacopoeia Commission. Pharmacopoeia of the People’s Republic of China; China Medical Science and Technology Press: Beijing, China, 2025; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.Y. Traditional Uses, Phytochemistry, Pharmacology, Pharmacokinetics and Quality Control of Polyporus umbellatus (Pers.) Fries: A Review. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2013, 149, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandara, A.R.; Rapior, S.; Bhat, D.J.; Kakumyan, P.; Chamyuang, S.; Xu, J.; Hyde, K.D. Polyporus umbellatus, an Edible-Medicinal Cultivated Mushroom with Multiple Developed Health-Care Products as Food, Medicine and Cosmetics: A Review. Cryptogam. Mycol. 2015, 36, 3–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.P.; Li, X.; Lai, G.N.; Li, J.H.; Jia, W.Y.; Cao, Y.Y.; Xu, W.X.; Tan, Q.L.; Zhou, C.Y.; Luo, M.; et al. Mechanisms of Macrophage Immunomodulatory Activity Induced by a New Polysaccharide Isolated from Polyporus umbellatus (Pers.) Fries. Front. Chem. 2020, 8, 581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Zhang, L.Z.; Wu, J.J.; Xu, Y.B.; Qi, S.L.; Liu, W.; Liu, P.; Shi, S.S.; Wang, H.J.; Zhang, Q.Y.; et al. Extraction, Characterization, and Anti-Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis Activity of a (1,3) (1,6)-β-D-Glucan from the Polyporus umbellatus (Pers.) Fries. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 230, 123252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, H.; Han, X.Q.; Gong, F.Y.; Dong, H.; Tu, P.F.; Gao, X.M. Structure Elucidation and Immunological Function Analysis of a Novel β-Glucan from the Fruit Bodies of Polyporus umbellatus (Pers.) Fries. Glycobiology 2012, 22, 1673–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, P.F.; Zhang, A.Q.; Zhang, F.M.; Linhardt, R.J.; Sun, P.L. Structure and Bioactivity of a Polysaccharide Containing Uronic Acid from Polyporus umbellatus Sclerotia. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 152, 222–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, C.F.; Hsieh, C.H.; Lin, W.Y. Proteomic Response of LAP-Activated RAW 264.7 Macrophages to the Anti-Inflammatory Property of Fungal Ergosterol. Food Chem. 2011, 126, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Yasukawa, K. New Anti-Inflammatory Ergostane-Type Ecdysteroids from the Sclerotium of Polyporus umbellatus. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2008, 18, 3417–3420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sekiya, N.; Hikiami, H.; Nakai, Y.; Sakakibara, I.; Nozaki, K.; Kouta, K.; Shimada, Y.; Terasawa, K. Inhibitory Effects of Triterpenes Isolated from Chuling (Polyporus umbellatus Fries) on Free Radical-Induced Lysis of Red Blood Cells. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2005, 28, 817–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, S.; Hernandez, M.; Kramer, J.K.G.; Rinker, D.L.; Tsao, R. Ergosterol Profiles, Fatty Acid Composition, and Antioxidant Activities of Button Mushrooms as Affected by Tissue Part and Developmental Stage. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 11616–11625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.Y.; Xie, R.M.; Chao, X.; Zhang, Y.M.; Lin, R.C.; Sun, W.J. Bioactivity-Directed Isolation, Identification of Diuretic Compounds from Polyporus umbellatus. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2009, 126, 184–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.Z.; Liu, H.; Sang, Q.; Sun, Y.F.; Li, L.; Chen, W.J. Polyporus umbellatus, a Precious Rare Fungus with Good Pharmaceutical and Food Value. Eng. Life Sci. 2025, 25, e202400048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Zhuang, S.Y.; Li, S.N.; Nong, Y.Y.; Zhang, Y.T.; Liang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, C. Rapid Screening, Isolation, and Activity Evaluation of Potential Xanthine Oxidase Inhibitors in Polyporus umbellatus and Mechanism of Action in the Treatment of Gout. Phytochem. Anal. 2024, 35, 116–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishida, H.; Inaoka, Y.; Shibatani, J.; Fukushima, M.; Tsuji, K. Studies of the Active Substances in Herbs Used for Hair Treatment. II. Isolation of Hair Regrowth Substances, Acetosyringone and Polyporusterone A and B, from Polyporus umbellatus Fries. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 1999, 22, 1189–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Gu, M.; Wang, Y.; Yu, R.; Weng, L.; Zhao, C.; Zhao, M. Comparative Study of Physicochemical Properties, Antioxidant Activity, Antitumor Activity and in Vitro Fermentation Prebiotic Properties of Polyporus umbellatus (Pers.) Fries Polysaccharides at Different Solvent Extractions. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 306, 141506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- State Council of the People’s Republic of China. Catalogue of National Key Protected Wild Medicinal Species. J. Pharm. Pract. Serv. 1988, 02, 82. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.C.; Yang, G. Current Problems and Countermeasures of Management of Valuable and Endangered Chinese Medicinal Materials. China J. Chin. Mater. Medica 2025, 50, 4081–4088. [Google Scholar]

- Didukh, Y.P.; Akimov, I.A. Chervona Knyha Ukrainy. Roslynnyi Svit (Red Data Book of Ukraine; Vegetable Kingdom); Globalconsulting: Kyiv, Ukraine, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Pasailiuk, M. Growing of Polyporus umbellatus. Curr. Res. Environ. Appl. Mycol. 2020, 10, 457–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, G.; Liu, D.X. Preliminary report on the artificial cultivation of Polyporus umbellatus. Shaanxi Med. J. 1978, 65–66, 58. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Kang, Y.; Qin, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Lei, M.; Guo, H. Genetic Diversity of Endangered Polyporus umbellatus from China Assessed Using a Sequence-Related Amplified Polymorphism Technique. Genet. Mol. Res. 2012, 11, 4121–4129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.M.; Xing, Y.M.; Guo, S.X. Diversity Analysis of Polyporus umbellatus in China Using Inter-Simple Sequence Repeat (ISSR) Markers. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2015, 38, 1512–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.Y. Development of EST-SSR Markers for Polyporus umbellatus and Genetic Diveristy. Master’s Thesis, Northwest A&F University, Xianyang, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, M.M.; Xing, Y.M.; Zhang, D.W.; Guo, S.X. Novel Microsatellite Markers Suitable for Genetic Studies in Polyporus umbellatus (Polyporales, Basidiomycota). Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2015, 61, 450–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parthiban, S.; Govindaraj, P.; Senthilkumar, S. Comparison of Relative Efficiency of Genomic SSR and EST-SSR Markers in Estimating Genetic Diversity in Sugarcane. 3 Biotech 2018, 8, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, X.; Ma, X.; Hart, M.M.; Wang, A.; Guo, S. Genetic Diversity and Evolution of Chinese Traditional Medicinal Fungus Polyporus umbellatus (Polyporales, Basidiomycota). PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e58807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P. Study on the Biological Characteristics of Grefola umbellata. Master’s Thesis, Northwest A & F University, Xianyang, China, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.Y.; Li, S.J.; Li, B.; Guo, S.X. Comparative Research Progress of Zhushiling and Jishiling. Chin. Pharm. J. 2024, 59, 2199–2204. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, W.W. Studies on the Constituents of Sclerotia and Fermented Mycelia of Polyporus umbellatus and the Quality Analysis. Ph.D. Thesis, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, Beijing, China, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, Q.; Li, M.; Zhou, J.; Guo, D.; Ren, M.; Wei, H. Analysis of Ergosterol and Polysaccharide Content in Polyporus umbellatus from Different Origins, Commodity Specifications, and Growth Durations. J. Chin. Med. Mater. 2015, 38, 45–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeWoody, J.A.; Harder, A.M.; Mathur, S.; Willoughby, J.R. The Long-Standing Significance of Genetic Diversity in Conservation. Mol. Ecol. 2021, 30, 4147–4154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, H.; Sun, J.; Chen, M.Y.; Dong, Y.; Wang, P.; Xu, J.; Shao, Q.; Wang, Z. The Impact of Non-Environmental Factors on the Chemical Variation of Radix Scrophulariae. Heliyon 2024, 10, e24468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamm, T.P.; Nowicki, M.; Boggess, S.L.; Ranney, T.G.; Trigiano, R.N. A Set of SSR Markers to Characterize Genetic Diversity in All Viburnum Species. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 5343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nantongo, J.S.; Odoi, J.B.; Agaba, H.; Gwali, S. SilicoDArT and SNP Markers for Genetic Diversity and Population Structure Analysis of Trema Orientalis; a Fodder Species. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0267464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nan, X.; Li, A.; Deng, W. Data Set of “Digital Mountain Map of China” 2015; National Tibetan Plateau/Third Pole Environment Data Center: Beijing, China, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhuang, W.Y. Designing Primer Sets for Amplification of Partial Calmodulin Gene for Penicillia. Mycosystema 2004, 23, 466–473. [Google Scholar]

- Beier, S.; Thiel, T.; Münch, T.; Scholz, U.; Mascher, M. MISA-Web: A Web Server for Microsatellite Prediction. Bioinformatics 2017, 33, 2583–2585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, J.L. Informativeness of Human (dC-dA)n. (dG-dT)n Polymorphisms. Genomics 1990, 7, 524–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, W.J.; Hao, Z.X.; Liu, K.J. Development and identification of SSR molecular markers based on whole genomic sequences of Punica granatum. J. Beijing For. Univ. 2019, 41, 38–47. [Google Scholar]

- Rozen, S.; Skaletsky, H. Primer3 on the WWW for General Users and for Biologist Programmers. Methods Mol. Biol. Clifton NJ 2000, 132, 365–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peakall, R.; Smouse, P.E. GenAlEx 6.5: Genetic Analysis in Excel. Population Genetic Software for Teaching and Research-an Update. Bioinforma. Oxf. Engl. 2012, 28, 2537–2539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Muse, S.V. PowerMarker: An Integrated Analysis Environment for Genetic Marker Analysis. Bioinforma. Oxf. Engl. 2005, 21, 2128–2129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, M.J.; Li, W.X.; Luo, P.; He, J.J.; Zhang, H.L.; Yan, Q.; Ye, Y.N. Genetic Diversity Analysis and Core Germplasm Bank Construction in Cold Resistant Germplasm of Rubber Trees (Hevea brasiliensis). Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 14533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Durbin, R. Fast and Accurate Short Read Alignment with Burrows–Wheeler Transform. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1754–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danecek, P.; Bonfield, J.K.; Liddle, J.; Marshall, J.; Ohan, V.; Pollard, M.O.; Whitwham, A.; Keane, T.; McCarthy, S.A.; Davies, R.M.; et al. Twelve Years of SAMtools and BCFtools. GigaScience 2021, 10, giab008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenna, A.; Hanna, M.; Banks, E.; Sivachenko, A.; Cibulskis, K.; Kernytsky, A.; Garimella, K.; Altshuler, D.; Gabriel, S.; Daly, M.; et al. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: A MapReduce Framework for Analyzing next-Generation DNA Sequencing Data. Genome Res. 2010, 20, 1297–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cingolani, P.; Platts, A.; Wang, L.L.; Coon, M.; Nguyen, T.; Wang, L.; Land, S.J.; Lu, X.; Ruden, D.M. A Program for Annotating and Predicting the Effects of Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms. Fly 2012, 6, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, D.H.; Novembre, J.; Lange, K. Fast Model-Based Estimation of Ancestry in Unrelated Individuals. Genome Res. 2009, 19, 1655–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Tamura, K. MEGA7: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 7.0 for Bigger Datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2016, 33, 1870–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.H.; Xie, M.Y.; Wang, F.M.; Luo, Z.; Li, C.; Wang, X.R. Classification of Panax Quinquefolium. L Sample by Cluster Analysis. J. Instrum. Anal. 2006, 20–24, 28. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.H. Development of SSR Markers Based on the Whole Genome of Sichuan Salvia miltiorrhiza. Master’s Thesis, Sichuan Agricultural University, Ya’an, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Han, P.; Chen, J.; Chen, Z.; Che, X.; Peng, Z.; Ding, P. Exploring Genetic Diversity and Population Structure in Cinnamomum cassia (L.) J. Presl Germplasm in China through Phenotypic, Chemical Component, and Molecular Marker Analyses. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1374648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.T.; Yi, X.R.; Zhou, M.W. Analysis of genetic diversity and population structure of pear germplasm resources in Guangxi. J. Fruit Sci. 2024, 41, 379–391. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, J.; Dai, X.; Chen, J.; Shuang, H.; Yuan, C.; Luo, D. Study on the Characteristics of Genetic Diversity and Population Structure of a Rare and Endangered Species of Rhododendron nymphaeoides (Ericaceae) Based on Microsatellite Markers. BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.; Li, X.; Zhao, Z.; Nawaz, Z. Predicting the Impacts of Climate Change, Soils and Vegetation Types on the Geographic Distribution of Polyporus umbellatus in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 648, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, K.H.; Yao, J.Q.; Zhao, W.P.; Yang, S.W. Study of Taibai mountain natural Grifola’s chemical component medicinal value and ecology distribution. Chin. Wild Plant Resour. 2008, 03, 25–27. [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw, M.J.; Aime, M.C.; Rokas, A.; Maust, A.; Moparthi, S.; Jellings, K.; Pane, A.M.; Hendricks, D.; Pandey, B.; Li, Y.; et al. Extensive Intragenomic Variation in the Internal Transcribed Spacer Region of Fungi. iScience 2023, 26, 107317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paloi, S.; Luangsa-ard, J.J.; Mhuantong, W.; Stadler, M.; Kobmoo, N. Intragenomic Variation in Nuclear Ribosomal Markers and Its Implication in Species Delimitation, Identification and Barcoding in Fungi. Fungal Biol. Rev. 2022, 42, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhang, X.; Garcia, S.; Leitch, A.R.; Kovařík, A. Intragenomic rDNA Variation—The Product of Concerted Evolution, Mutation, or Something in Between? Heredity 2023, 131, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, F.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, D.; Tang, X.Z.; Wang, P.F.; He, X.X.; Zhang, Y.R.; Dong, J.Y.; Cao, Y.; Liu, C.L.; et al. Evidence for Inbreeding and Genetic Differentiation among Geographic Populations of the Saprophytic Mushroom Trogia venenata from Southwestern China. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0149507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branco, S.; Bi, K.; Liao, H.-L.; Gladieux, P.; Badouin, H.; Ellison, C.E.; Nguyen, N.H.; Vilgalys, R.; Peay, K.G.; Taylor, J.W.; et al. Continental-Level Population Differentiation and Environmental Adaptation in the Mushroom Suillus brevipes. Mol. Ecol. 2017, 26, 2063–2076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.L.; Zhang, L.J.; Shang, X.D.; Peng, B.; Li, Y.; Xiao, S.J.; Tan, Q.; Fu, Y.P. Chromosomal Genome and Population Genetic Analyses to Reveal Genetic Architecture, Breeding History and Genes Related to Cadmium Accumulation in Lentinula edodes. BMC Genom. 2022, 23, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.Q.; Ouyang, J.P.; Shao, J.; Xu, C.M.; Sun, Q.B.; Ji, X.H.; He, G. Quality evaluation of medicinal Polyporus umbellatus from online commerce. Edible Fungi China 2023, 42, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favre, A.; Päckert, M.; Pauls, S.U.; Jähnig, S.C.; Uhl, D.; Michalak, I.; Muellner-Riehl, A.N. The Role of the Uplift of the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau for the Evolution of Tibetan Biotas. Biol. Rev. 2015, 90, 236–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.; Tong, J.; Lee, C.W.; Ha, S.; Eom, S.H.; Im, Y.J. Structural Mechanism of Ergosterol Regulation by Fungal Sterol Transcription Factor Upc2. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 6129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bi, Y.P.; Miao, Y.; Han, Y.; Xu, J.; Wang, Q. Biological and Physicochemical Properties of Two Polysaccharides from the Mycelia of Grifola umbellate. Carbohydr. Polym. 2013, 95, 740–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billiard, S.; López-Villavicencio, M.; Devier, B.; Hood, M.E.; Fairhead, C.; Giraud, T. Having Sex, Yes, but with Whom? Inferences from Fungi on the Evolution of Anisogamy and Mating Types. Biol. Rev. 2011, 86, 421–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malloure, B.D.; James, T.Y. Inbreeding Depression in Urban Environments of the Bird’s Nest Fungus Cyathus stercoreus (Nidulariaceae: Basidiomycota). Heredity 2013, 110, 355–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tibayrenc, M.; Ayala, F.J. Reproductive Clonality of Pathogens: A Perspective on Pathogenic Viruses, Bacteria, Fungi, and Parasitic Protozoa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, E3305–E3313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holsinger, K.E. Reproductive Systems and Evolution in Vascular Plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 7037–7042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brejon Lamartinière, E.; Tremble, K.; Dentinger, B.T.M.; Dasmahapatra, K.K.; Hoffman, J.I. Runs of Homozygosity Reveal Contrasting Histories of Inbreeding across Global Lineages of the Edible Porcini Mushroom, Boletus edulis. Mol. Ecol. 2024, 33, e17470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodenburg, S.Y.A.; Terhem, R.B.; Veloso, J.; Stassen, J.H.M.; van Kan, J.A.L. Functional Analysis of Mating Type Genes and Transcriptome Analysis during Fruiting Body Development of Botrytis cinerea. mBio 2018, 9, e01939-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.J.; Li, B.; Xu, X.L.; Liu, Y.Y.; Xing, Y.M.; Guo, S.X. Insight into the Nuclear Distribution Patterns of Conidia and the Asexual Life Cycle of Polyporus umbellatus. Fungal Biol. 2024, 128, 2032–2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Xu, J.; Xiao, P. Research progress on the biological characteristics of Polyporus umbellatus. China J. Chin. Mater. Medica 1996, 9, 3–5. [Google Scholar]

| No. | Primer | Type | Direction | Sequence (5′–3′) | Repeat Motif | TA (°C) | Allelic Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | F1 | gSSR | F | CCCCGCGAAGACTTGTATGA | (AT)15 | 56 | 232 |

| R | TGTATGTGCTTACTGGCCCG | ||||||

| O | F15 | gSSR | F | CGACTACGGTCAGCCACTAC | (AG)12 | 58 | 151 |

| R | TCTCTCTCTCTGCGTCGTCA | ||||||

| P | F16 | gSSR | F | ACACGTGTGGGATTCAACGT | (AC)11 | 54 | 230 |

| R | ACGCATCCATGAACGTCTGA | ||||||

| R | F18 | gSSR | F | GCATTGTGTTGGGCCAAGAG | (AG)8 | 56 | 111 |

| R | ACCAGAACCTTCCTTGTGCC | ||||||

| S | F19 | gSSR | F | GTAGACCGTGCTAGTGGCTC | (TGTA)6 | 58 | 144 |

| R | GGGTGAGAGTGTGACTTGGG | ||||||

| U | F21 | gSSR | F | TCGTTGACCTTGCCTTGTCT | (GTAA)5 | 54 | 109 |

| R | GCGTCAGATTGACCACTCCA | ||||||

| W | F23 | gSSR | F | CATCCCCCTCGCATGATACC | (TGC)8 | 58 | 207 |

| R | GCGGGGTACTATTTGCCGTA | ||||||

| Z | F26 | gSSR | F | GTTGTGCTGCTGGGCTATTG | (ATT)6 | 56 | 221 |

| R | CAAGCCCTGCTGTGAAAACC | ||||||

| f | F32 | gSSR | F | TGTGCCTTTCGCCATCTCTT | (TC)9 | 54 | 109 |

| R | GAGAGGGAGGCTACTGACCA | ||||||

| r | F44 | gSSR | F | GGACCACCGCCAATTTGTTC | (TCA)8 | 56 | 148 |

| R | GGGTTCCCAGTCACAGGATG | ||||||

| s | F45 | gSSR | F | GGTGTACGAGGTGGAAGCAA | (GGC)8 | 56 | 103 |

| R | CGCGAAGAAAGCCCAGAATG | ||||||

| t | F46 | gSSR | F | TGGTGTGCCCAACTTTAGCA | (GAT)8 | 54 | 118 |

| R | GTGTCCGATCACTAGCCTCG | ||||||

| F | F6 | gSSR | F | TGGGAATGGGTAGTCCGAGT | (GGA)13 | 56 | 112 |

| R | AATGAGCGTCGTCATTTGCG | ||||||

| H | F8 | gSSR | F | TTGTTGGCGGTTGCAATCAG | (CCT)12 | 54 | 131 |

| R | TTGGTTCGTAGGACGTGGTG | ||||||

| β | PUF14 | EST-SSR | F | CTCGCATCTCCACCATCTCC | (CGC)5 | 58 | 250 |

| R | CCTCTCACTTTCCCTCGAGC | ||||||

| ε | PUF16 | EST-SSR | F | GTCCCTGTAGTCGCTTCTCG | (GAC)7 | 56 | 230 |

| R | AGTTGGAGAGACAAGCGTGG | ||||||

| ζ | PUF17 | EST-SSR | F | CCAGACATGCTCGACACTCA | (TCCA)5 | 56 | 130 |

| R | GTGATGGATGTGGGGAAGGG | ||||||

| η | PUF31 | EST-SSR | F | CCAAGACCCCGCAAACCTAT | (GGC)5 | 56 | 140 |

| R | GTTGGGTGTGGCGAATTTCC | ||||||

| γ | PUF33 | EST-SSR | F | ATCCTCAGAGTCACCCCCTC | (TCA)6 | 58 | 270 |

| R | CGACGCGAGGATGAGAATGA | ||||||

| δ | PUF35 | EST-SSR | F | CTTTCTTGCGTGCCCTTTCC | (GCT)6 | 58 | 300 |

| R | AAGGTCAGGAATGCTTCGGG |

| Primers | No. of Observed Allele | No. of Effective Alleles | Shannon’s Information Index | Observed Heterozygosity | Expected Heterozygosity | Polymorphic Information Content |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Na) | (Ne) | (I) | (Ho) | (He) | (PIC) | |

| F15 | 2 | 2 | 0.69 | 0.62 | 0.5 | 0.37 |

| F16 | 10 | 4.88 | 1.79 | 0.31 | 0.8 | 0.77 |

| F19 | 2 | 1.66 | 0.59 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.32 |

| F21 | 2 | 1.27 | 0.37 | 0.11 | 0.21 | 0.19 |

| F26 | 6 | 3.79 | 1.5 | 0.11 | 0.74 | 0.69 |

| F44 | 5 | 2.3 | 1.13 | 0.38 | 0.56 | 0.53 |

| F45 | 3 | 2.81 | 1.06 | 0.2 | 0.64 | 0.57 |

| F46 | 7 | 5.16 | 1.76 | 0.35 | 0.81 | 0.78 |

| F6 | 3 | 1.87 | 0.72 | 0.1 | 0.46 | 0.37 |

| PUF14 | 5 | 3.27 | 1.31 | 0.34 | 0.69 | 0.64 |

| PUF16 | 4 | 3.35 | 1.3 | 0.21 | 0.7 | 0.65 |

| PUF17 | 3 | 1.65 | 0.69 | 0 | 0.39 | 0.35 |

| PUF31 | 4 | 1.92 | 0.92 | 0.05 | 0.48 | 0.44 |

| PUF33 | 7 | 3.08 | 1.39 | 0.06 | 0.68 | 0.64 |

| PUF35 | 9 | 4.85 | 1.83 | 0.37 | 0.79 | 0.77 |

| Mean | 5 | 2.92 | 1.14 | 0.22 | 0.59 | 0.54 |

| Source of Variation | Degrees of Freedom (df) | Sum of Squares (SS) | Mean Square (MS) | Estimated Variance (Est. Var.) | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Among Populations | 5 | 101.139 | 20.228 | 0.803 | 15% |

| Among Individuals | 46 | 340.342 | 7.399 | 2.964 | 57% |

| Within Individuals | 52 | 76.500 | 1.471 | 1.471 | 28% |

| Total | 103 | 517.981 | 29.098 | 5.238 | 100% |

| Na | Ne | I | Ho | He | PIC | FIS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group1 | 4 | 2.28 | 0.86 | 0.32 | 0.46 | 0.28 | 0.30 |

| Group2 | 3 | 2.14 | 0.77 | 0.19 | 0.45 | 0.22 | 0.58 |

| Group4 | 2 | 2.17 | 0.78 | 0.09 | 0.50 | 0.13 | 0.82 |

| Group5 | 3 | 2.17 | 0.84 | 0.15 | 0.50 | 0.14 | 0.70 |

| Group6 | 3 | 2.06 | 0.81 | 0.17 | 0.47 | 0.10 | 0.64 |

| Mean | 3 | 2.16 | 0.81 | 0.18 | 0.48 | 0.17 | 0.61 |

| Na | Ne | I | Ho | He | PIC | FIS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qinba Mountain | 4 | 2.58 | 0.98 | 0.29 | 0.51 | 0.41 | 0.43 |

| Hengduan Mountain | 3 | 2.61 | 0.96 | 0.14 | 0.55 | 0.28 | 0.75 |

| Changbai Mountain | 3 | 2.16 | 0.86 | 0.18 | 0.51 | 0.32 | 0.65 |

| Wumeng Mountain | 3 | 2.08 | 0.80 | 0.14 | 0.49 | 0.17 | 0.71 |

| Mean | 3 | 2.35 | 0.90 | 0.19 | 0.52 | 0.30 | 0.63 |

| Na | Ne | I | Ho | He | PIC | FIS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zhushiling | 5 | 2.77 | 1.07 | 0.27 | 0.54 | 0.46 | 0.50 |

| Jishiling | 3 | 2.28 | 0.91 | 0.15 | 0.53 | 0.43 | 0.72 |

| Mean | 4 | 2.52 | 0.99 | 0.21 | 0.54 | 0.45 | 0.61 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Liu, Y.; Li, S.; Liu, L.; Li, B.; Guo, S. Genetic–Geographic–Chemical Framework of Polyporus umbellatus Reveals Lineage-Specific Chemotypes for Elite Medicinal Line Breeding. J. Fungi 2026, 12, 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof12010039

Liu Y, Li S, Liu L, Li B, Guo S. Genetic–Geographic–Chemical Framework of Polyporus umbellatus Reveals Lineage-Specific Chemotypes for Elite Medicinal Line Breeding. Journal of Fungi. 2026; 12(1):39. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof12010039

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Youyan, Shoujian Li, Liu Liu, Bing Li, and Shunxing Guo. 2026. "Genetic–Geographic–Chemical Framework of Polyporus umbellatus Reveals Lineage-Specific Chemotypes for Elite Medicinal Line Breeding" Journal of Fungi 12, no. 1: 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof12010039

APA StyleLiu, Y., Li, S., Liu, L., Li, B., & Guo, S. (2026). Genetic–Geographic–Chemical Framework of Polyporus umbellatus Reveals Lineage-Specific Chemotypes for Elite Medicinal Line Breeding. Journal of Fungi, 12(1), 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof12010039