Combined Transcriptomic and Metabolomic Analyses of the Response of Ganoderma lucidum to Elevated CO2

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Culture Conditions and Acquisition of the G. lucidum Samples

2.2. Metabolomic Analysis

2.2.1. Sample Preparation and LC-MS Analysis

2.2.2. Metabolite Identification and Quantification

2.3. Transcriptome Analysis

2.3.1. Transcriptome Sequencing

2.3.2. Transcriptome Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Comparison of Metabolomic Data

3.1.1. Quality Control of the Metabolome Data

3.1.2. Differential Metabolic Profile of G. lucidum Cultivated Under Elevated CO2 Conditions

3.1.3. Effects of Elevated CO2 Conditions on Bioactive Compounds in the G. lucidum Fruiting Body

3.2. Comparison of Transcriptomic Data

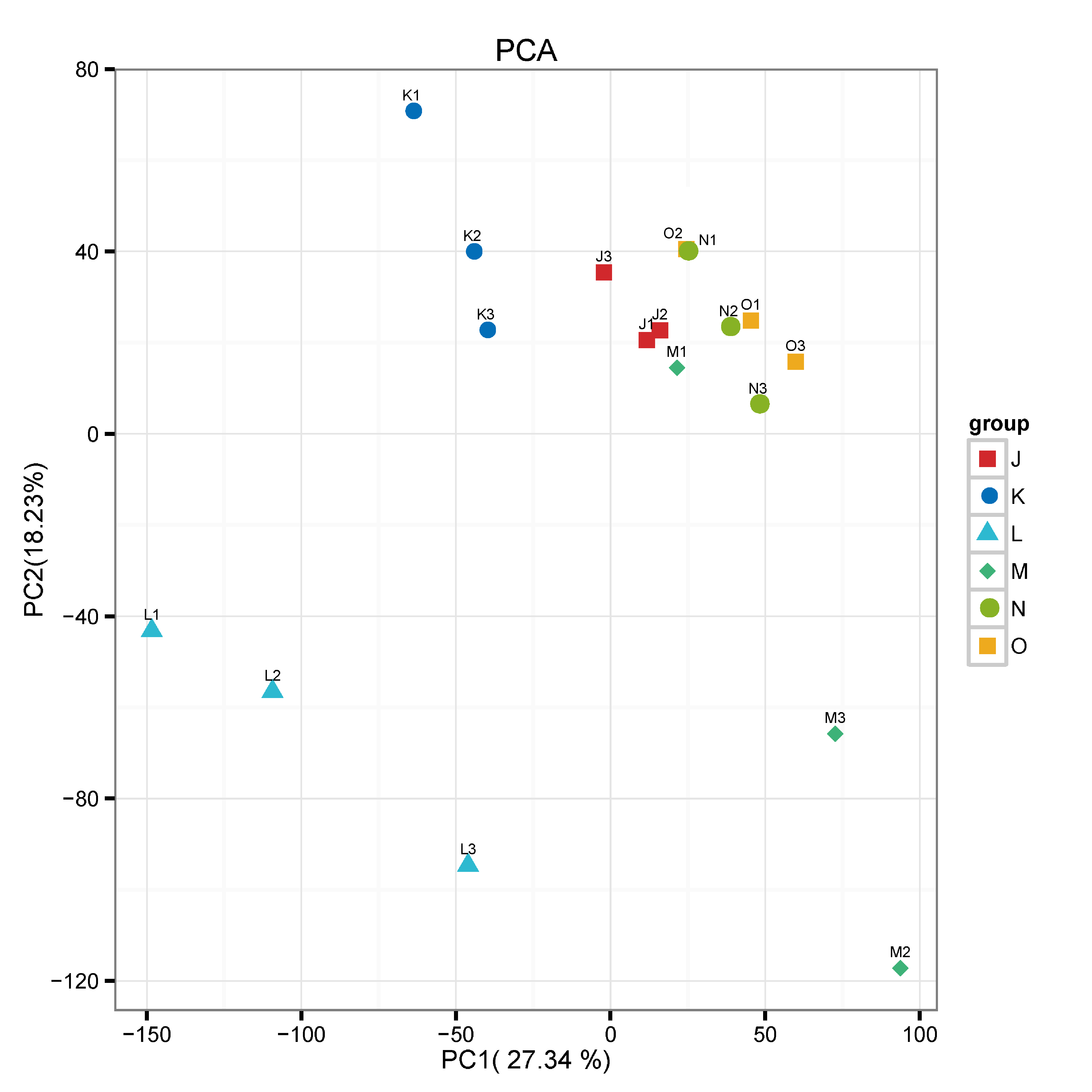

3.2.1. Quality Assessment of Transcriptome Data

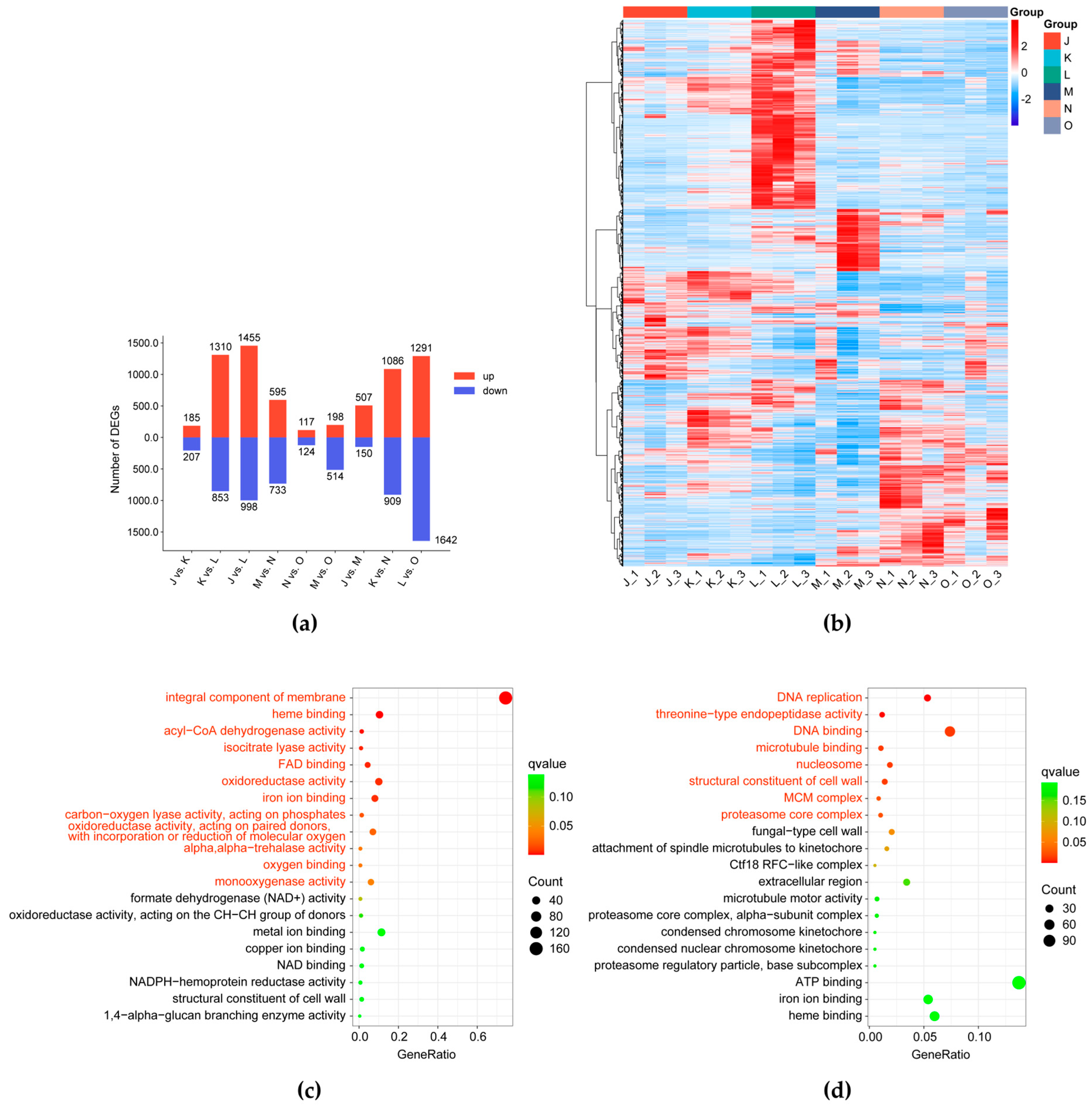

3.2.2. Differential Transcriptomic Profile of G. lucidum Cultivated Under Elevated CO2 Conditions

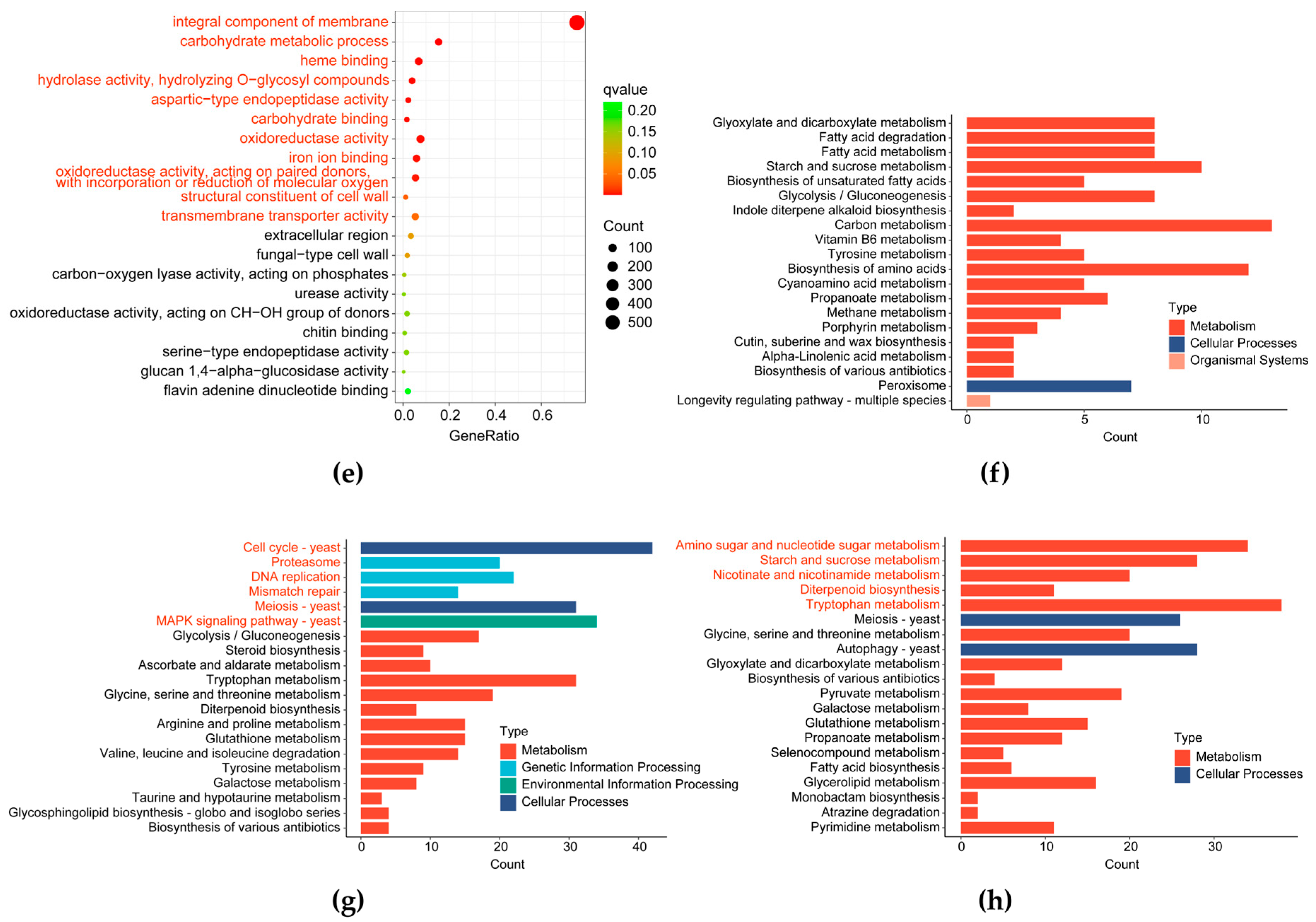

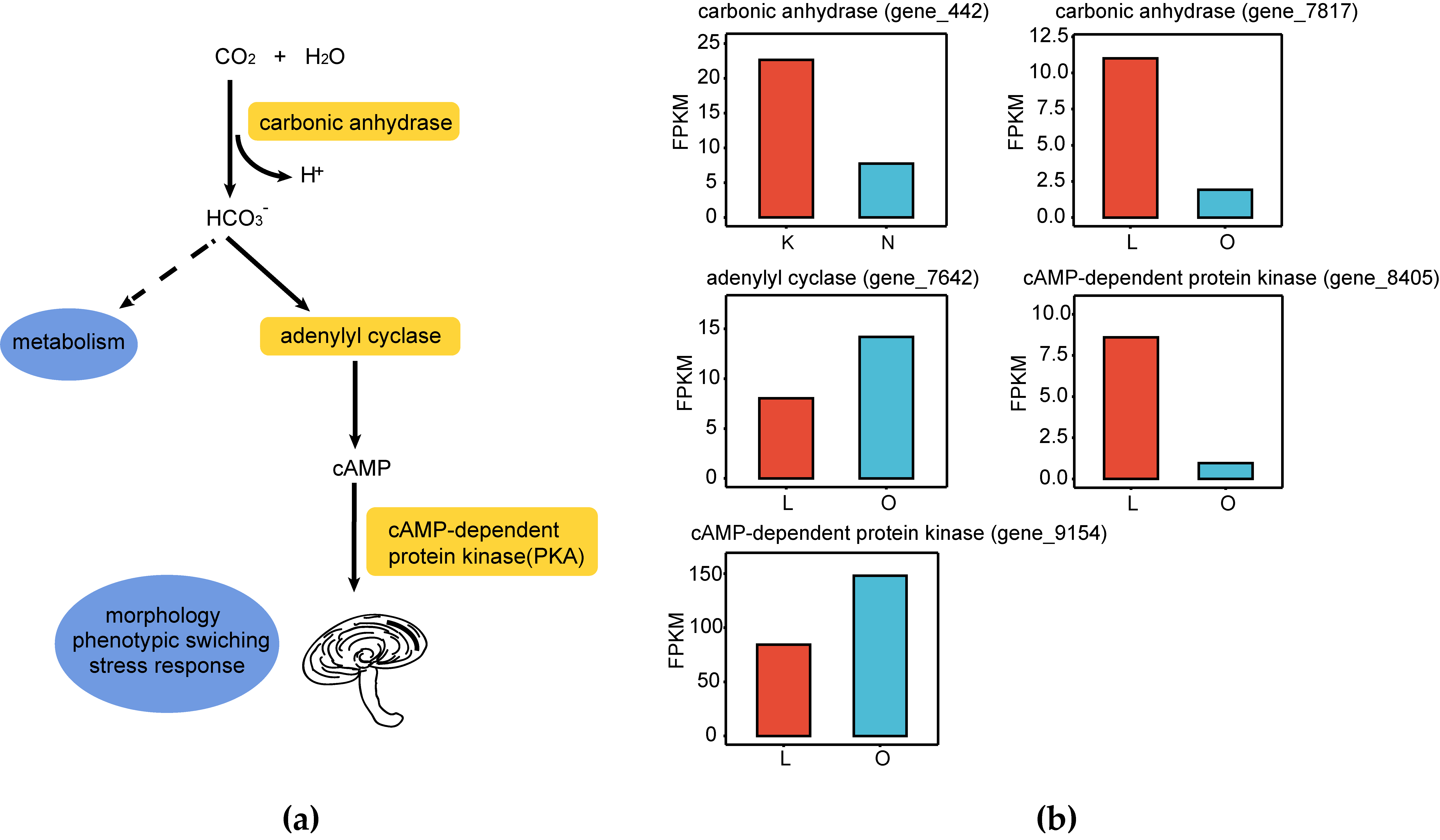

3.2.3. Analysis of Pathways Responding to CO2 Concentration

3.2.4. Analysis of Pathways Related to Cell Division and Proliferation

3.2.5. Analysis of Pathways Related to Cell Wall Components

3.3. Integrated Analysis of Transcriptomics and Metabolomics

4. Discussion

4.1. Energy Metabolic Remodeling of G. lucidum Under Elevated CO2

4.2. High CO2 Concentrations Inhibit Cell Division and Proliferation Pathways in G. lucidum

4.3. High CO2 Concentrations Regulate Cell Wall Synthesis and Remodeling in G. lucidum

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ahmad, R.; Riaz, M.; Khan, A.; Aljamea, A.; Algheryafi, M.; Sewaket, D.; Alqathama, A. Ganoderma lucidum (Reishi) an edible mushroom; a comprehensive and critical review of its nutritional, cosmeceutical, mycochemical, pharmacological, clinical, and toxicological properties. Phytother. Res. PTR 2021, 35, 6030–6062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Tian, L.; Wang, Y.; Li, Z.; Xu, Z. Chemodiversity, pharmacological activity, and biosynthesis of specialized metabolites from medicinal model fungi Ganoderma lucidum. Chin. Med. 2024, 19, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, R.-W.; Gao, Y.-Q.; Xia, B.; Wang, J.-Y.; Liu, X.-N.; Tang, J.-J.; Yin, X.; Gao, J.-M. Ganoderterpene A, a new triterpenoid from Ganoderma lucidum, attenuates LPS-induced inflammation and apoptosis via suppressing MAPK and TLR-4/NF-κB pathways in BV-2 cells. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 12730–12740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, C.; Guo, D.; Fang, L.; Sang, T.; Wu, J.; Guo, C.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Chen, C.; Chen, J.; et al. Ganoderma lucidum polysaccharide modulates gut microbiota and immune cell function to inhibit inflammation and tumorigenesis in colon. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 267, 118231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abulizi, A.; Hu, L.; Ma, A.; Shao, F.-Y.; Zhu, H.-Z.; Lin, S.-M.; Shao, G.-Y.; Xu, Y.; Ran, J.-H.; Li, J.; et al. Ganoderic acid alleviates chemotherapy-induced fatigue in mice bearing colon tumor. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2021, 42, 1703–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.-Q.; Zhang, Y.-J.; Tian, Z.-K. Anti-Oxidant, Anti-Inflammatory and Anti-Fibrosis Effects of ganoderic acid a on carbon tetrachloride induced nephrotoxicity by regulating the Trx/TrxR and JAK/ROCK pathway. Chem.-Biol. Interact. 2021, 344, 109529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, J.; Yong, T.; Huang, L.; Chen, S.; Xiao, C.; Wu, Q.; Hu, H.; Xie, Y.; Li, X.; Liu, Y.; et al. A Ganoderma lucidum polysaccharide F31 alleviates hyperglycemia through kidney protection and adipocyte apoptosis. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 226, 1178–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.; Han, J.; Wang, K.; Han, H.; Hu, Y.; Li, H.; Wu, S.; Zhang, L. Research progress of Ganoderma lucidum polysaccharide in prevention and treatment of atherosclerosis. Heliyon 2024, 10, e33307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, X.-C.; Wu, Q.; Cao, Y.-J.; Lin, Y.-C.; Guo, W.-L.; Rao, P.-F.; Zhang, Y.-Y.; Chen, Y.-T.; Ai, L.-Z.; Ni, L. Ganoderic acid a from Ganoderma lucidum protects against alcoholic liver injury through ameliorating the lipid metabolism and modulating the intestinal microbial composition. Food Funct. 2022, 13, 5820–5837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; Shao, N.; Fang, Z.; Ouyang, Z.; Shen, Y.; Yang, R.; Liu, H.; Cai, B.; Wei, T. The anti-Alzheimer’s disease effects of ganoderic acid a by inhibiting ferroptosis-lipid peroxidation via activation of the NRF2/SLC7A11/GPX4 signaling pathway. Chem.-Biol. Interact. 2025, 412, 111459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eastwood, D.C.; Herman, B.; Noble, R.; Dobrovin-Pennington, A.; Sreenivasaprasad, S.; Burton, K.S. Environmental regulation of reproductive phase change in Agaricus bisporus by 1-Octen-3-Ol, temperature and CO2. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2013, 55, 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.-J.; Tong, Z.-J.; Liu, Y.-Y.; Li, Y.-N.; Zhao, C.; Mukhtar, I.; Tao, Y.-X.; Chen, B.-Z.; Deng, Y.-J.; Xie, B.-G. Comparative transcriptomics of Flammulina filiformis suggests a high CO2 concentration inhibits early pileus expansion by decreasing cell division control pathways. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 5923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Dong, Y.; Wang, P.; Zhu, P.; Li, Y.; Lai, Y.; Liu, J.; Liu, Q. Cauliflower-shaped Pleurotus ostreatus cultivated in an atmosphere with high environmental carbon dioxide concentration. Mycologia 2023, 115, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinugawa, K.; Suzuki, A.; Takamatsu, Y.; Kato, M.; Tanaka, K. Effects of concentrated carbon dioxide on the fruiting of several cultivated basidiomycetes (II). Mycoscience 1994, 35, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, K.-Y.; Jhune, C.-S.; Park, J.-S.; Cho, S.-M.; Weon, H.-Y.; Cheong, J.-C.; Choi, S.-G.; Sung, J.-M. Characterization of fruitbody morphology on various environmental conditions in Pleurotus ostreatus. Mycobiology 2003, 31, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzam, Z.S.; Sharabi, K.; Guetta, J.; Bank, E.M.; Gruenbaum, Y. The physiological and molecular effects of elevated CO2 levels. Cell Cycle 2010, 9, 1528–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Su, C.; Ray, S.; Yuan, Y.; Liu, H. CO2 signaling through the Ptc2-Ssn3 axis governs sustained hyphal development of Candida albicans by reducing Ume6 phosphorylation and degradation. mBio 2019, 10, e02320-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, R.; Zhang, L.; Yang, X.; Li, Q.; Zhang, C.; Guo, L.; Yu, H.; Yu, H. Responses of the mushroom Pleurotus ostreatus under different CO2 concentration by comparative proteomic analyses. J. Fungi 2022, 8, 652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.-W.; Park, C.-H.; Lee, S.-C.; Shin, J.-H.; Park, Y.-J. High carbon dioxide concentration inhibits pileus growth of Flammulina velutipes by downregulating cyclin gene expression. J. Fungi 2025, 11, 551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, B.S.; Nakamura, N.; Miyashiro, H.; Bae, K.W.; Hattori, M. Triterpenes from the spores of Ganoderma lucidum and their inhibitory activity against HIV-1 protease. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1998, 46, 1607–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mau, J.-L.; Lin, H.-C.; Chen, C.-C. Non-volatile components of several medicinal mushrooms. Food Res. Int. 2001, 34, 521–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, O.-C.; Lee, C.-S.; Park, Y.-J. SNP and SCAR markers for specific discrimination of antler-shaped Ganoderma lucidum. Microorganisms 2019, 7, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sudheer, S.; Taha, Z.; Manickam, S.; Ali, A.; Cheng, P.G. Development of antler-type fruiting bodies of Ganoderma lucidum and determination of its biochemical properties. Fungal Biol. 2018, 122, 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wijayawardene, N.N.; Boonyuen, N.; Ranaweera, C.B.; de Zoysa, H.K.S.; Padmathilake, R.E.; Nifla, F.; Dai, D.-Q.; Liu, Y.; Suwannarach, N.; Kumla, J.; et al. OMICS and other advanced technologies in mycological applications. J. Fungi 2023, 9, 688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arshadi, N.; Nouri, H.; Moghimi, H. Increasing the production of the bioactive compounds in medicinal mushrooms: An omics perspective. Microb. Cell Fact. 2023, 22, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahn, Y.-S.; Mühlschlegel, F.A. CO2 sensing in fungi and beyond. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2006, 9, 572–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, R.; Pohlers, S.; Mühlschlegel, F.A.; Kurzai, O. CO2 sensing in fungi: At the heart of metabolic signaling. Curr. Genet. 2017, 63, 965–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.-Y.; Tong, Z.-J.; Li, Y.-N.; Yan, J.-J.; Zhao, C.; Yao, S.; Li, B.-Y.; Xie, B.-G. CA gene superfamily and its expressions in response to CO2 in Flammulina filiformis. Mycosystema 2020, 38, 2249–2257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gow, N.A.R.; Latge, J.-P.; Munro, C.A. The fungal cell wall: Structure, biosynthesis, and function. Microbiol. Spectr. 2017, 5, 10–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niederpruem, D.J. Role of carbon dioxide in the control of fruiting of Schizophyllum commune. J. Bacteriol. 1963, 85, 1300–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, E.M. Development of excised sporocarps of Agaricus bisporus and its control by CO2. Trans. Br. Mycol. Soc. 1977, 69, 183–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Roux, P. The effect of carbon dioxide on the metabolism of the Agaricus bisporus sporophore. I. Organic and Free Amino Acids. Mushroom Sci. 1969, 7, 31–36. Available online: https://eurekamag.com/research/014/730/014730333.php (accessed on 7 October 2025).

- Lin, Q.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Liu, W.; Guan, W.; Wang, Z. Effects of high CO2 in-package treatment on flavor, quality and antioxidant activity of button mushroom (Agaricus bisporus) during postharvest storage. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2017, 123, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, L.; Zheng, Y.; Lian, D.; Zhong, X.; Liu, X. Production of triterpenoids from Ganoderma lucidum: Elicitation strategy and signal transduction. Process Biochem. 2018, 69, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.-N.; Chen, Y.-L.; Zhang, Z.-J.; Wu, F.-Y.; Wang, H.-J.; Wang, X.-L.; Liu, G.-Q. Phosphatidic acid directly activates mTOR and then regulates SREBP to promote ganoderic acid biosynthesis under heat stress in Ganoderma lingzhi. Commun. Biol. 2024, 7, 1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Zhu, F.; Zhu, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhou, H.; Chen, S.; Ruan, J. Transcriptome profiling of transcription factors in Ganoderma lucidum in response to methyl jasmonate. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 1052377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, C.E.; Ahmad, R.; Goh, Y.K.; Azizan, K.A.; Baharum, S.N.; Goh, K.J. Growth modulation and metabolic responses of Ganoderma boninense to salicylic acid stress. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0262029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, J.; Wang, L.; Tang, X.; Liu, R.; Shi, L.; Zhu, J.; Zhao, M. Glsirt1-mediated deacetylation of GlCAT regulates intracellular ROS levels, affecting ganoderic acid biosynthesis in Ganoderma lucidum. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2024, 216, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, T.; Shi, L.; Zhang, T.; Ren, A.; Jiang, A.; Yu, H.; Zhao, M. Cross talk between calcium and reactive oxygen species regulates hyphal branching and ganoderic acid biosynthesis in Ganoderma lucidum under copper stress. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2018, 84, e00438-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.-L.; Ren, A.; Wang, T.; Zhu, J.; Hu, Y.-R.; Shi, L.; Yu, H.-S.; Zhao, M.-W. Hydrogen Sulfide, a novel small molecule signalling agent, participates in the regulation of ganoderic acids biosynthesis induced by heat stress in Ganoderma lucidum. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2019, 130, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Yue, S.; Gao, T.; Zhu, J.; Ren, A.; Yu, H.; Wang, H.; Zhao, M. Nitrate reductase-dependent nitric oxide plays a key role on MeJA-induced ganoderic acid biosynthesis in Ganoderma lucidum. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020, 104, 10737–10753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, A.M.; Wilken, P.M.; van der Nest, M.A.; Wingfield, M.J.; Wingfield, B.D. It’s All in the Genes: The regulatory pathways of sexual reproduction in filamentous ascomycetes. Genes 2019, 10, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sørensen, J.G.; Kristensen, T.N.; Loeschcke, V. The evolutionary and ecological role of heat shock proteins. Ecol. Lett. 2003, 6, 1025–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Yang, J.; Qi, Z.; Wu, H.; Wang, B.; Zou, F.; Mei, H.; Liu, J.; Wang, W.; Liu, Q. Heat shock proteins: Biological functions, pathological roles, and therapeutic opportunities. MedComm 2022, 3, e161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiwari, S.; Thakur, R.; Shankar, J. Role of heat-shock proteins in cellular function and in the biology of fungi. Biotechnol. Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 132635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, G.; Duan, J.; Fick, W.; Candau, J.-N. Molecular characterization of eight ATP-dependent heat shock protein transcripts and their expression profiles in response to stresses in the spruce budworm, Choristoneura fumiferana (L.). J. Therm. Biol. 2020, 88, 102493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kregel, K.C. Heat shock proteins: Modifying factors in physiological stress responses and acquired thermotolerance. J. Appl. Physiol. 2002, 92, 2177–2186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.-Y.; Chang, M.-C.; Meng, J.-L.; Feng, C.-P.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, M.-L. Comparative proteome reveals metabolic changes during the fruiting process in Flammulina velutipes. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 65, 5091–5100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Lin, R.; Xu, K.; Guo, L.; Yu, H. Comparative proteomic analysis within the developmental stages of the mushroom white Hypsizygus marmoreus. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, H.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Q.; Huang, J.; Juan, J.; Kuai, B.; Feng, Z.; Chen, H. Transcriptome and differentially expressed gene profiles in mycelium, primordium and fruiting body development in Stropharia rugosoannulata. Genes 2022, 13, 1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.-Y.; Kim, D.-H.; Kim, J.-M. Comparative transcriptome analysis of dikaryotic mycelia and mature fruiting bodies in the edible mushroom Lentinula edodes. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 8983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodenburg, S.Y.A.; Terhem, R.B.; Veloso, J.; Stassen, J.H.M.; van Kan, J.A.L. Functional analysis of mating type genes and transcriptome analysis during fruiting body development of Botrytis cinerea. Mbio 2018, 9, e01939-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genschik, P.; Marrocco, K.; Bach, L.; Noir, S.; Criqui, M.-C. Selective protein degradation: A rheostat to modulate cell-cycle phase transitions. J. Exp. Bot. 2014, 65, 2603–2615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marshall, R.S.; Vierstra, R.D. Dynamic regulation of the 26S proteasome: From synthesis to degradation. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2019, 6, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, S.; Veri, A.O.; Cowen, L.E. The Proteasome Governs Fungal Morphogenesis via Functional Connections with Hsp90 and cAMP-Protein Kinase a Signaling. Mbio 2020, 11, e00290-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, J.; Jung, W.H.; Kronstad, J.W. The cAMP/protein kinase A signaling pathway in pathogenic basidiomycete fungi: Connections with iron homeostasis. J. Microbiol. 2015, 53, 579–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Liu, J.; Hou, Z.; Luo, X.; Lin, J.; Jiang, N.; Hou, L.; Ma, L.; Li, C.; Qu, S. Activation of mycelial defense mechanisms in the oyster mushroom Pleurotus ostreatus induced by Tyrophagus putrescentiae. Food Res. Int. 2022, 160, 111708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Xie, W.; Zhang, R.; Wang, F.; Wen, Q.; Hu, Y.; Liu, Q.; Shen, J. Transcription factor Pofst3 regulates Pleurotus ostreatus development by targeting multiple biological pathways. Fungal Biol. 2024, 128, 2295–2304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemos Junior, W.J.F.; Viel, A.; Bovo, B.; Carlot, M.; Giacomini, A.; Corich, V. Saccharomyces cerevisiae vineyard strains have different nitrogen requirements that affect their fermentation performances. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2017, 65, 381–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lengeler, K.B.; Davidson, R.C.; D’souza, C.; Harashima, T.; Shen, W.C.; Wang, P.; Pan, X.; Waugh, M.; Heitman, J. Signal transduction cascades regulating fungal development and virulence. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2000, 64, 746–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmer, G.E.; Horton, J.S. Mushrooms by magic: Making connections between signal transduction and fruiting body development in the basidiomycete fungus Schizophyllum commune. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2006, 262, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickwella Widanage, M.C.; Gautam, I.; Sarkar, D.; Mentink-Vigier, F.; Vermaas, J.V.; Ding, S.-Y.; Lipton, A.S.; Fontaine, T.; Latgé, J.-P.; Wang, P.; et al. Adaptative survival of Aspergillus fumigatus to echinocandins arises from cell wall remodeling beyond β-1,3-glucan synthesis inhibition. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 6382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gow, N.A.R.; Lenardon, M.D. Architecture of the dynamic fungal cell wall. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2023, 21, 248–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.-H.; Huang, Z.-X.; Luo, X.-H.; Chen, H.; Weng, B.-Q.; Wang, Y.-X.; Chen, L.-S. Comparative transcriptome analysis reveals candidate genes related to cadmium accumulation and tolerance in two almond mushroom (Agaricus brasiliensis) strains with contrasting cadmium tolerance. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0239617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, L.; Wang, L.; Liu, R.; Zhu, J.; Shi, L.; Ren, A.; Chen, H.; Zhao, M. The GCN4-Swi6B module mediates low nitrogen-induced cell wall remodeling in Ganoderma lucidum. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2025, 91, e0016425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, L.; Wang, J.; Li, T.; Zhang, B.; Yan, K.; Zhang, Z.; Geng, X.; Chang, M.; Meng, J. Transcriptome analysis revealed that cell wall regulatory pathways are involved in the tolerance of Pleurotus ostreatus mycelia to different heat stresses. J. Fungi 2025, 11, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sietsma, J.H.; Rast, D.; Wessels, J.G.H. The effect of carbon dioxide on fruiting and on the degradation of a cell-wall glucan in Schizophyllum commune. Microbiology 1977, 102, 385–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, M.; Sakuraba, S.; Shibata, K.; Inatomi, S.; Okazaki, M.; Shimosaka, M. Cloning and characterization of a gene coding for a hydrophobin, Fv-Hyd1, specifically expressed during fruiting body development in the basidiomycete Flammulina velutipes. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2005, 67, 240–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiao, J.; Liu, H.; Xue, P.; Hong, M.; Guo, X.; Xing, Z.; Zhao, M.; Zhu, J. Function of a hydrophobin in growth and development, nitrogen regulation, and abiotic stress resistance of Ganoderma lucidum. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2023, 370, fnad051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wessels, J.G.H. Gene expression during fruiting in Schizophyllum Commune. Mycol. Res. 1992, 96, 609–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugones, L.G.; Wösten, H.A.B.; Birkenkamp, K.U.; Sjollema, K.A.; Zagers, J.; Wessels, J.G.H. Hydrophobins line air channels in fruiting bodies of Schizophyllum commune and Agaricus bisporus. Mycol. Res. 1999, 103, 635–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Wetter, M.A.; Wösten, H.A.; Wessels, J.G. SC3 and SC4 hydrophobins have distinct roles in formation of aerial structures in dikaryons of Schizophyllum commune. Mol. Microbiol. 2000, 36, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagy, L.G.; Vonk, P.J.; Künzler, M.; Földi, C.; Virágh, M.; Ohm, R.A.; Hennicke, F.; Bálint, B.; Csernetics, Á.; Hegedüs, B.; et al. Lessons on fruiting body morphogenesis from genomes and transcriptomes of agaricomycetes. Stud. Mycol. 2023, 104, 1–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, D.; Gao, Q.; Rong, C.; Liu, Y.; Song, S.; Yu, Q.; Zhou, K.; Liao, Y. Comparative transcriptome analysis of abnormal cap and healthy fruiting bodies of the edible mushroom Lentinula edodes. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2021, 156, 103614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Bi, J.; Kang, L.; Zhou, J.; Liu, X.; Liu, Z.; Yuan, S. The molecular mechanism of stipe cell wall extension for mushroom stipe elongation growth. Fungal Biol. Rev. 2021, 35, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Fang, T.; Chen, L.; Yao, H.; Li, Y.; Liu, G.; Wu, S.; Lan, J.; Chen, X. Combined Transcriptomic and Metabolomic Analyses of the Response of Ganoderma lucidum to Elevated CO2. J. Fungi 2026, 12, 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof12010005

Fang T, Chen L, Yao H, Li Y, Liu G, Wu S, Lan J, Chen X. Combined Transcriptomic and Metabolomic Analyses of the Response of Ganoderma lucidum to Elevated CO2. Journal of Fungi. 2026; 12(1):5. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof12010005

Chicago/Turabian StyleFang, Tingting, Lu Chen, Hui Yao, Ye Li, Guohui Liu, Shaofeng Wu, Jin Lan, and Xiangdong Chen. 2026. "Combined Transcriptomic and Metabolomic Analyses of the Response of Ganoderma lucidum to Elevated CO2" Journal of Fungi 12, no. 1: 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof12010005

APA StyleFang, T., Chen, L., Yao, H., Li, Y., Liu, G., Wu, S., Lan, J., & Chen, X. (2026). Combined Transcriptomic and Metabolomic Analyses of the Response of Ganoderma lucidum to Elevated CO2. Journal of Fungi, 12(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof12010005