Quantitative Morphological Profiling and Isolate-Specific Insensitivity of Cacao Pathogens to Novel Bio-Based Phenolic Amides

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Biobased Compounds

2.2. Fungal Isolates and Culture Conditions

2.3. Antifungal Activity Assay

2.4. Image Acquisition and Quantitative Morphological Profiling

2.5. Statistical Analysis and Machine Learning

3. Results

3.1. Antifungal Effects on Pestalotiopsis sp. (CGH5)

3.2. C. gloeosporioides Isolate CGH17

3.3. Growth Inhibition and Altered Morphology of C. gloeosporioides Isolate CGH49

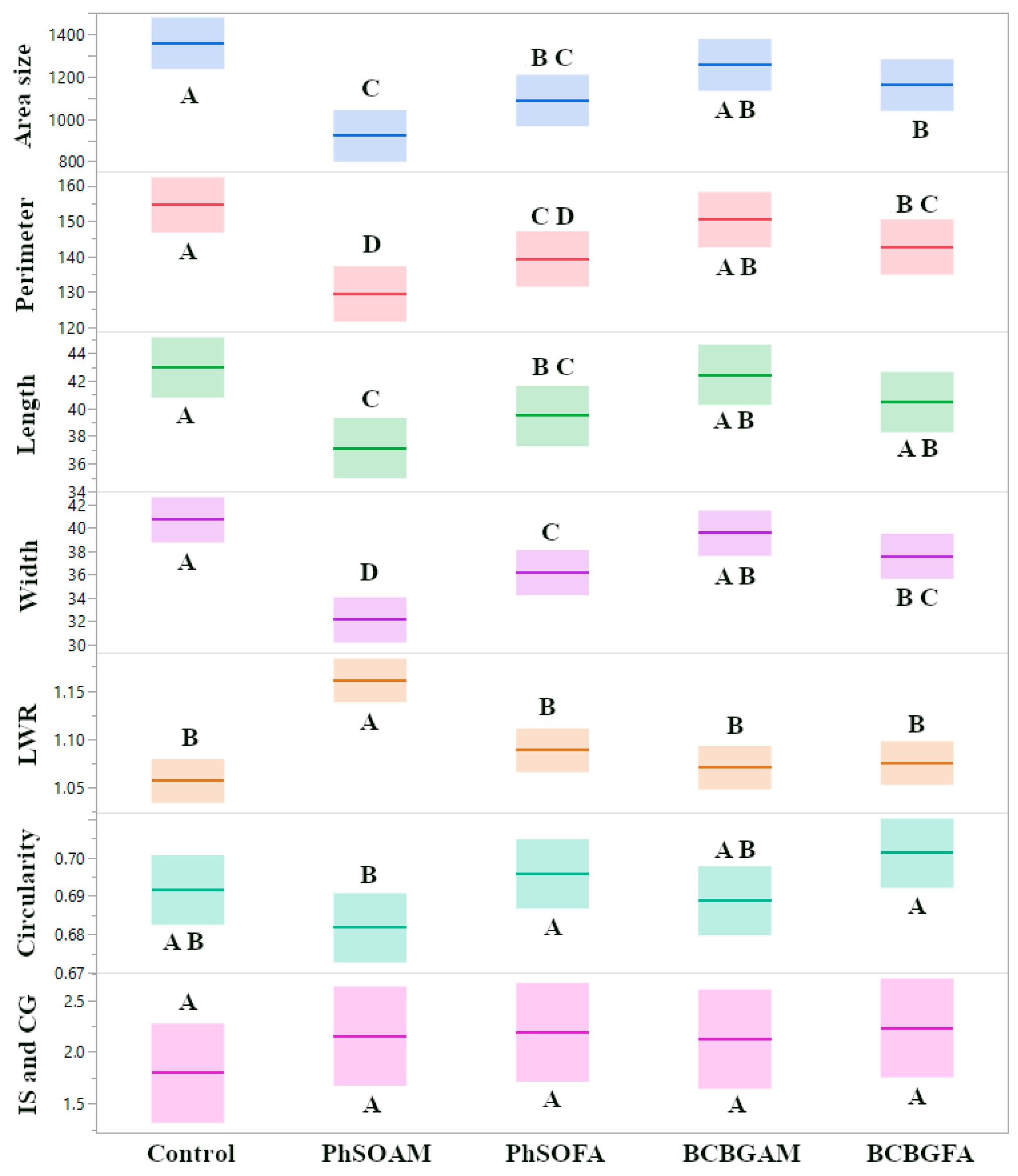

3.4. Comparative Antifungal Effects Across All Isolates

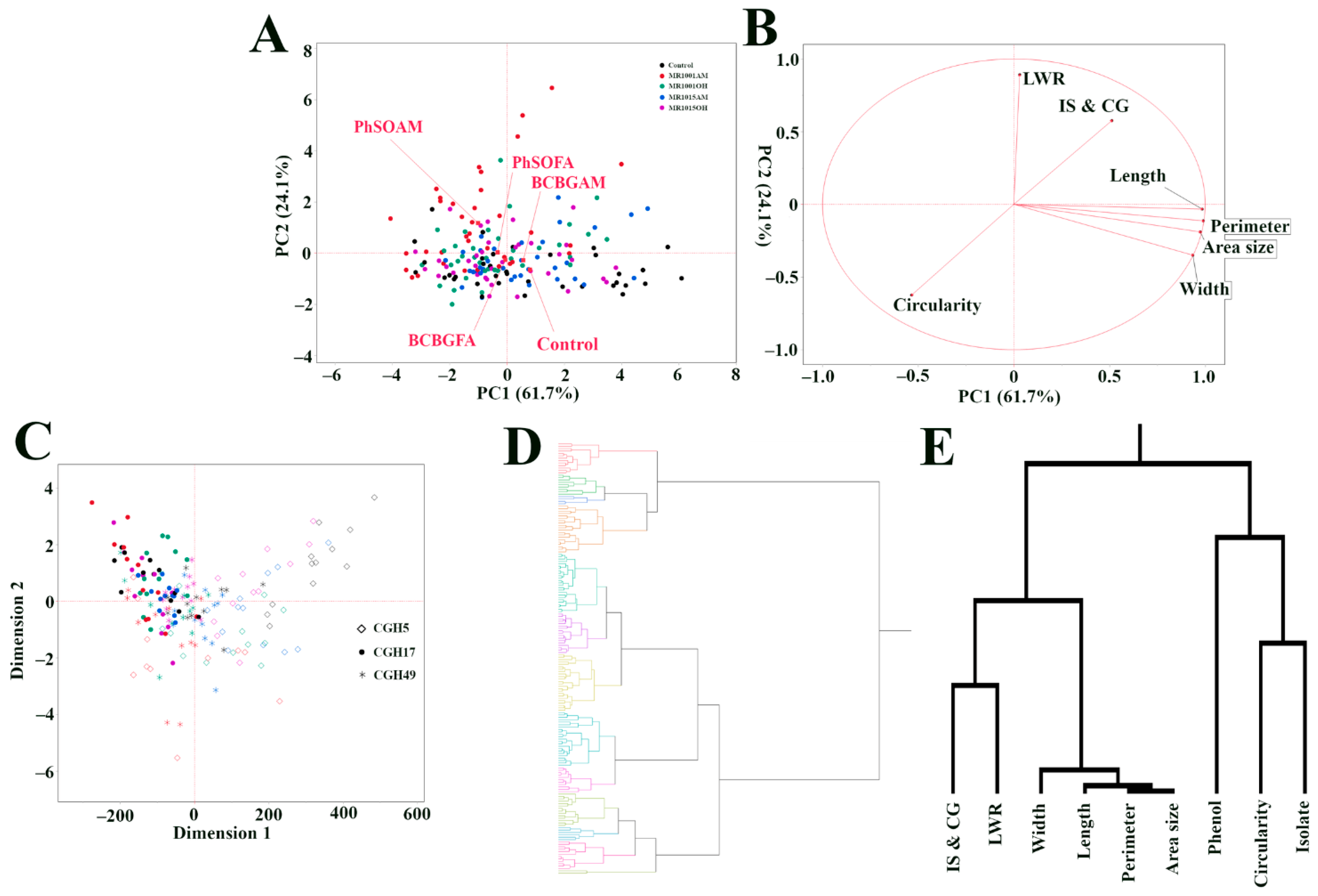

3.5. Multivariate Analyses Uncover Complex Interplay Between Fungal Isolate Identity, Phenolic Compound Treatment, and Colony Morphology

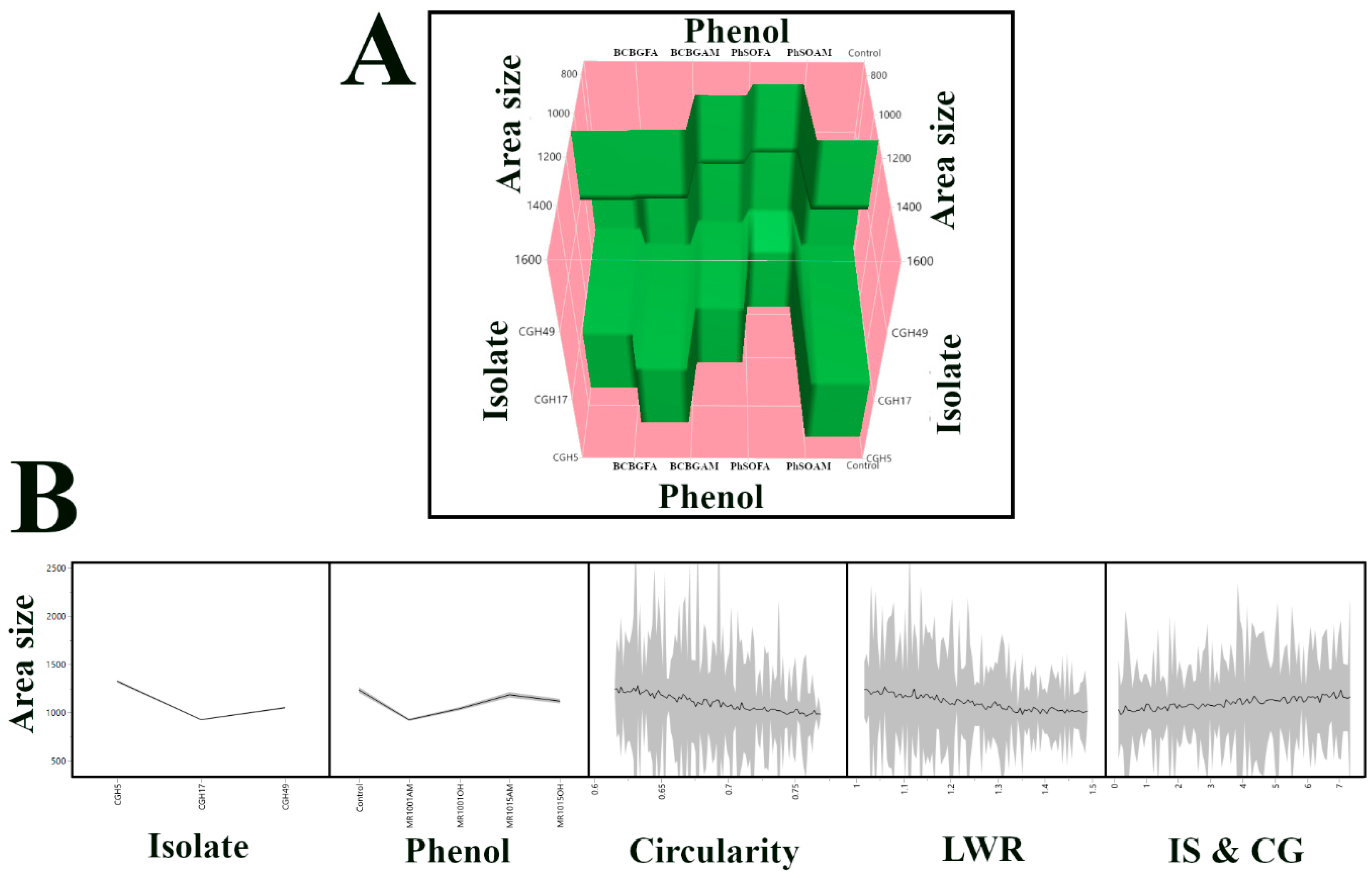

3.6. Machine Learning Model Selection and Feature Importance Analysis for Predicting Fungal Colony Area

4. Discussion

4.1. Structure–Activity Relationship and Sustainable Design

4.2. Morphological Disruption as a Key to Virulence Suppression

4.3. Resistance Mechanisms in C. gloeosporioides CGH17

4.4. A Morpho-Predictive Approach to Antifungal Screening

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Anand, G.; Rajeshkumar, K.C. Challenges and Threats Posed by Plant Pathogenic Fungi on Agricultural Productivity and Economy. In Fungal Diversity, Ecology and Control Management; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 483–493. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Montenegro, J. Livelihood Strategies and Risk Behavior of Cacao Producers in Ecuador: Effects of National Policies to Support Cacao Farmers and Specialty Cacao Landraces. Ph.D. Thesis, Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya, Barcelona, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, J.N. Applying a One Health Approach to Study the Livelihoods of Cocoa Farming Communities in Bougainville. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Akrofi, A.Y.; Amoako-Atta, I.; Acheampong, K.; Assuah, M.K.; Melnick, R.L. Fruit and Canopy Pathogens of Unknown Potential Risk. In Cacao Diseases: A History of Old Enemies and New Encounters; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 361–382. [Google Scholar]

- Asare, E.; Domfeh, O.; Avicor, S.; Pobee, P.; Bukari, Y.; Amoako-Attah, I. Colletotrichum Gloeosporioides Sl Causes an Outbreak of Anthracnose of Cacao in Ghana. S. Afr. J. Plant Soil 2021, 38, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drenth, A.; Guest, D.I. Fungal and Oomycete Diseases of Tropical Tree Fruit Crops. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2016, 54, 373–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sureshkumar, D.; Emmanuel, C.J.; De Costa, D.M. Anthracnose of Grapevines in Sri Lanka: Pathogen Identification, Epidemiological Insights, and In Vitro Evaluation of Bioactive Extracts. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2025, 139, 102771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceresini, P.C.; Silva, T.C.; Vicentini, S.N.C.; Júnior, R.P.L.; Moreira, S.I.; Castro-Ríos, K.; Garcés-Fiallos, F.R.; Krug, L.D.; de Moura, S.S.; da Silva, A.G. Strategies for Managing Fungicide Resistance in the Brazilian Tropical Agroecosystem: Safeguarding Food Safety, Health, and the Environmental Quality. Trop. Plant Pathol. 2024, 49, 36–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ons, L.; Bylemans, D.; Thevissen, K.; Cammue, B.P. Combining Biocontrol Agents with Chemical Fungicides for Integrated Plant Fungal Disease Control. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thind, T. Changing Trends in Discovery of New Fungicides: A Perspective. Indian Phytopathol. 2021, 74, 875–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbar, M.U.; Aqeel, M.; Shah, M.S.; Jeelani, G.; Iqbal, N.; Latif, A.; Elnour, R.O.; Hashem, M.; Alzoubi, O.M.; Habeeb, T. Molecular Regulation of Antioxidants and Secondary Metabolites Act in Conjunction to Defend Plants against Pathogenic Infection. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2023, 161, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Abedin, M.M.; Singh, A.K.; Das, S. Role of Phenolic Compounds in Plant-Defensive Mechanisms. Plant Phenolics Sustain. Agric. 2020, 1, 517–532. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz, J.M.; Romero, L. Bioactivity of the Phenolic Compounds in Higher Plants. Stud. Nat. Prod. Chem. 2001, 25, 651–681. [Google Scholar]

- Dembitsky, V.M. Microbiological Aspects of Unique, Rare, and Unusual Fatty Acids Derived from Natural Amides and Their Pharmacological Profile. Microbiol. Res. 2022, 13, 377–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roemer, T.; Xu, D.; Singh, S.B.; Parish, C.A.; Harris, G.; Wang, H.; Davies, J.E.; Bills, G.F. Confronting the Challenges of Natural Product-Based Antifungal Discovery. Chem. Biol. 2011, 18, 148–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanvir, R.; Javeed, A.; Rehman, Y. Fatty Acids and Their Amide Derivatives from Endophytes: New Therapeutic Possibilities from a Hidden Source. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2018, 365, fny114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.-W.; Zhong, X.-J.; Zhao, Y.-S.; Rajoka, M.S.R.; Hashmi, M.H.; Zhai, P.; Song, X. Antifungal Natural Products and Their Derivatives: A Review of Their Activity and Mechanism of Actions. Pharmacol. Res. Mod. Chin. Med. 2023, 7, 100262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Białecka-Florjańczyk, E.; Fabiszewska, A.; Zieniuk, B. Phenolic Acids Derivatives-Biotechnological Methods of Synthesis and Bioactivity. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2018, 19, 1098–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, R.; Kaur, R.; Singh, R.; Bhardwaj, U.; Sharma, P. Isolation and Derivatization of Bioactive Compounds from Saussurea Lappa Roots with Antifungal Efficacy against Plant Pathogenic Fungi. J. Biol. Act. Prod. Nat. 2024, 14, 551–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ōmura, S.; Katagiri, M.; Awaya, J.; Furukawa, T.; Umezawa, I.; Ōi, N.; Mizoguchi, M.; Aoki, B.; Shindo, M. Relationship between the Structures of Fatty Acid Amide Derivatives and Their Antimicrobial Activities. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1974, 6, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Sun, Y.; Li, H.; Lai, Y.; Zhao, T.; Meng, Y.; Pan, X.; Lin, R.; Song, L. Design, Synthesis and Antifungal Activities of Novel Cis-Enamides via Intermediate Derivatization Method. Adv. Agrochem 2023, 2, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Fan, X.; Ashby, R.; Ngo, H. Structure-Activity Relationship of Antibacterial Bio-Based Epoxy Polymers Made from Phenolic Branched Fatty Acids. Prog. Org. Coat. 2021, 155, 106228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazem-Rostami, M.; Ryu, V.; Wagner, K.; Jones, K.; Mullen, C.A.; Wyatt, V.; Wu, C.; Ashby, R.; Fan, X.; Ngo, H. Antibacterial Agents from Waste Grease: Arylation of Brown Grease Fatty Acids with Beechwood Creosote and Derivatization. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 17760–17768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, H.; Wagner, K.; Cermak, S.; Fan, X.; Kazem-Rostami, M.; Sarker, M.I.; Ryu, V.; Elkasabi, Y. Branched-Chain Fatty Acids Based On Biomass Fast Pyrolysis Phenolics. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2025, 127, e70002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mota Fernandes, C.; Del Poeta, M. Fungal Sphingolipids: Role in the Regulation of Virulence and Potential as Targets for Future Antifungal Therapies. Expert Rev. Anti-Infect. Ther. 2020, 18, 1083–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paluch, E.; Szperlik, J.; Czuj, T.; Cal, M.; Lamch, Ł.; Wilk, K.; Obłąk, E. Multifunctional Cationic Surfactants with a Labile Amide Linker as Efficient Antifungal Agents—Mechanisms of Action. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2021, 105, 1237–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camiletti, B.X.; Lichtemberg, P.S.; Paredes, J.A.; Carraro, T.A.; Velascos, J.; Michailides, T.J. Characterization, Pathogenicity, and Fungicide Sensitivity of Alternaria Isolates Associated with Preharvest Fruit Drop in California Citrus. Fungal Biol. 2022, 126, 277–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Z.; Wakade, R.S.; Ribeiro, A.A.; Hu, W.; Bittinger, K.; Simon-Soro, A.; Kim, D.; Li, J.; Krysan, D.J.; Liu, Y. Human Tooth as a Fungal Niche: Candida Albicans Traits in Dental Plaque Isolates. mBio 2023, 14, e02769-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, R.S.; Robbins, N.; Cowen, L.E. Regulatory Circuitry Governing Fungal Development, Drug Resistance, and Disease. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2011, 75, 213–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, I.; Bhatt, J.; Jang, J.H.; Lim, S.; Lovelace, A.; Cha, M.; Lakshman, D.; Kim, M.S.; Meinhardt, L.W.; Park, S.; et al. Dissecting Trichoderma Antagonism: Role of Strain Identity, Volatiles, Biomass, and Morphology in Suppressing Cacao Pathogens. Biol. Control 2025, 207, 105807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, I.; Lim, S.; Jang, J.H.; Hong, S.M.; Prom, L.K.; Kirubakaran, S.; Cohen, S.P.; Lakshman, D.; Kim, M.S.; Meinhardt, L.W. Pathogen-Specific Stomatal Responses in Cacao Leaves to Phytophthora Megakarya and Rhizoctonia Solani. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 10584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanabata, T.; Shibaya, T.; Hori, K.; Ebana, K.; Yano, M. SmartGrain: High-Throughput Phenotyping Software for Measuring Seed Shape through Image Analysis. Plant Physiol. 2012, 160, 1871–1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimberg, R. Fundamentals of Predictive Analytics with JMP; Sas Institute: Cary, NC, USA, 2023; ISBN 1-68580-001-7. [Google Scholar]

- Schwenk, H.; Bengio, Y. Boosting Neural Networks. Neural Comput. 2000, 12, 1869–1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Chen, C.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, Z. Feature Selection for Support Vector Machines with RBF Kernel. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2011, 36, 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, L.E. K-Nearest Neighbor. Scholarpedia 2009, 4, 1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random Forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T. Introduction to Boosted Trees. Univ. Wash. Comput. Sci. 2014, 22, 14–40. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Y.-Y.; Ying, L. Decision Tree Methods: Applications for Classification and Prediction. Shanghai Arch. Psychiatry 2015, 27, 130. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hoerl, A.E.; Kennard, R.W. Ridge Regression: Biased Estimation for Nonorthogonal Problems. Technometrics 1970, 12, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar Sarangi, P.; Subudhi, S.; Bhatia, L.; Saha, K.; Mudgil, D.; Prasad Shadangi, K.; Srivastava, R.K.; Pattnaik, B.; Arya, R.K. Utilization of Agricultural Waste Biomass and Recycling toward Circular Bioeconomy. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 8526–8539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maina, S.; Kachrimanidou, V.; Koutinas, A. A Roadmap towards a Circular and Sustainable Bioeconomy through Waste Valorization. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2017, 8, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gow, N.A.; Brown, A.J.; Odds, F.C. Fungal Morphogenesis and Host Invasion. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2002, 5, 366–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virag, A.; Harris, S.D. The Spitzenkörper: A Molecular Perspective. Mycol. Res. 2006, 110, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz, A.B.; García, R.; Rodríguez-Peña, J.M.; Arroyo, J. The CWI Pathway: Regulation of the Transcriptional Adaptive Response to Cell Wall Stress in Yeast. J. Fungi 2018, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibe, C.; Munro, C.A. Fungal Cell Wall Proteins and Signaling Pathways Form a Cytoprotective Network to Combat Stresses. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geoghegan, I.; Steinberg, G.; Gurr, S. The Role of the Fungal Cell Wall in the Infection of Plants. Trends Microbiol. 2017, 25, 957–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuda, S.; Yamamoto, R.; Yanagisawa, N.; Takaya, N.; Sato, Y.; Riquelme, M.; Takeshita, N. Trade-off between Plasticity and Velocity in Mycelial Growth. mBio 2021, 12, e03196-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortaga, C.Q.; Cordez, B.W.P.; Dacones, L.S.; Balendres, M.A.O.; Dela Cueva, F.M. Mutations Associated with Fungicide Resistance in Colletotrichum Species: A Review. Phytoparasitica 2023, 51, 569–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Lu, D.; Tian, C. Analysis of Melanin Biosynthesis in the Plant Pathogenic Fungus Colletotrichum Gloeosporioides. Fungal Biol. 2021, 125, 679–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ikeda, R.; Sugita, T.; Jacobson, E.S.; Shinoda, T. Effects of Melanin upon Susceptibility of Cryptococcus to Antifungals. Microbiol. Immunol. 2003, 47, 271–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnabel, G.; Tan, Q.; Schneider, V.; Ishii, H. Inherent Tolerance of Colletotrichum Gloeosporioides to Fludioxonil. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2021, 172, 104767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, M.-C.; Rinker, D.C.; LaBella, A.L.; Opulente, D.A.; Wolters, J.F.; Zhou, X.; Shen, X.-X.; Groenewald, M.; Hittinger, C.T.; Rokas, A. Machine Learning Identifies Novel Signatures of Antifungal Drug Resistance in Saccharomycotina Yeasts. bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Trait | Number of Splits | Sum of Squares | Importance Score | Portion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isolate | 12 | 6,378,636.02 | 18 | 0.57 |

| Treatment type | 32 | 3,552,597.75 | 10 | 0.32 |

| LWR | 17 | 527,857.844 | 1 | 0.047 |

| IS & CG | 25 | 442,316.736 | 1 | 0.039 |

| Circularity | 20 | 323,315.082 | 0 | 0.029 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ahn, E.; Kazem-Rostami, M.; Park, S.; Ashby, R.D.; Ngo, H.; Meinhardt, L.W. Quantitative Morphological Profiling and Isolate-Specific Insensitivity of Cacao Pathogens to Novel Bio-Based Phenolic Amides. J. Fungi 2026, 12, 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof12010033

Ahn E, Kazem-Rostami M, Park S, Ashby RD, Ngo H, Meinhardt LW. Quantitative Morphological Profiling and Isolate-Specific Insensitivity of Cacao Pathogens to Novel Bio-Based Phenolic Amides. Journal of Fungi. 2026; 12(1):33. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof12010033

Chicago/Turabian StyleAhn, Ezekiel, Masoud Kazem-Rostami, Sunchung Park, Richard D. Ashby, Helen Ngo, and Lyndel W. Meinhardt. 2026. "Quantitative Morphological Profiling and Isolate-Specific Insensitivity of Cacao Pathogens to Novel Bio-Based Phenolic Amides" Journal of Fungi 12, no. 1: 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof12010033

APA StyleAhn, E., Kazem-Rostami, M., Park, S., Ashby, R. D., Ngo, H., & Meinhardt, L. W. (2026). Quantitative Morphological Profiling and Isolate-Specific Insensitivity of Cacao Pathogens to Novel Bio-Based Phenolic Amides. Journal of Fungi, 12(1), 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof12010033