Antifungal Susceptibility and Resistance-Associated Gene Expression in Nosocomial Candida Isolates

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Clinical Setting and Laboratory Assessment

2.3. Samples Collection Isolates

2.4. Strains Identification of Candida Species

2.5. Antifungal Susceptibility Testing (AFST)

2.6. Inducible Expression of Resistance-Related Genes Under Antifungal Exposure

2.7. RNA Extraction

2.8. Reverse Transcription Protocol

2.9. Primer Design for Antifungal Resistance Genes

2.10. Expression Analysis of Target Genes

2.11. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics

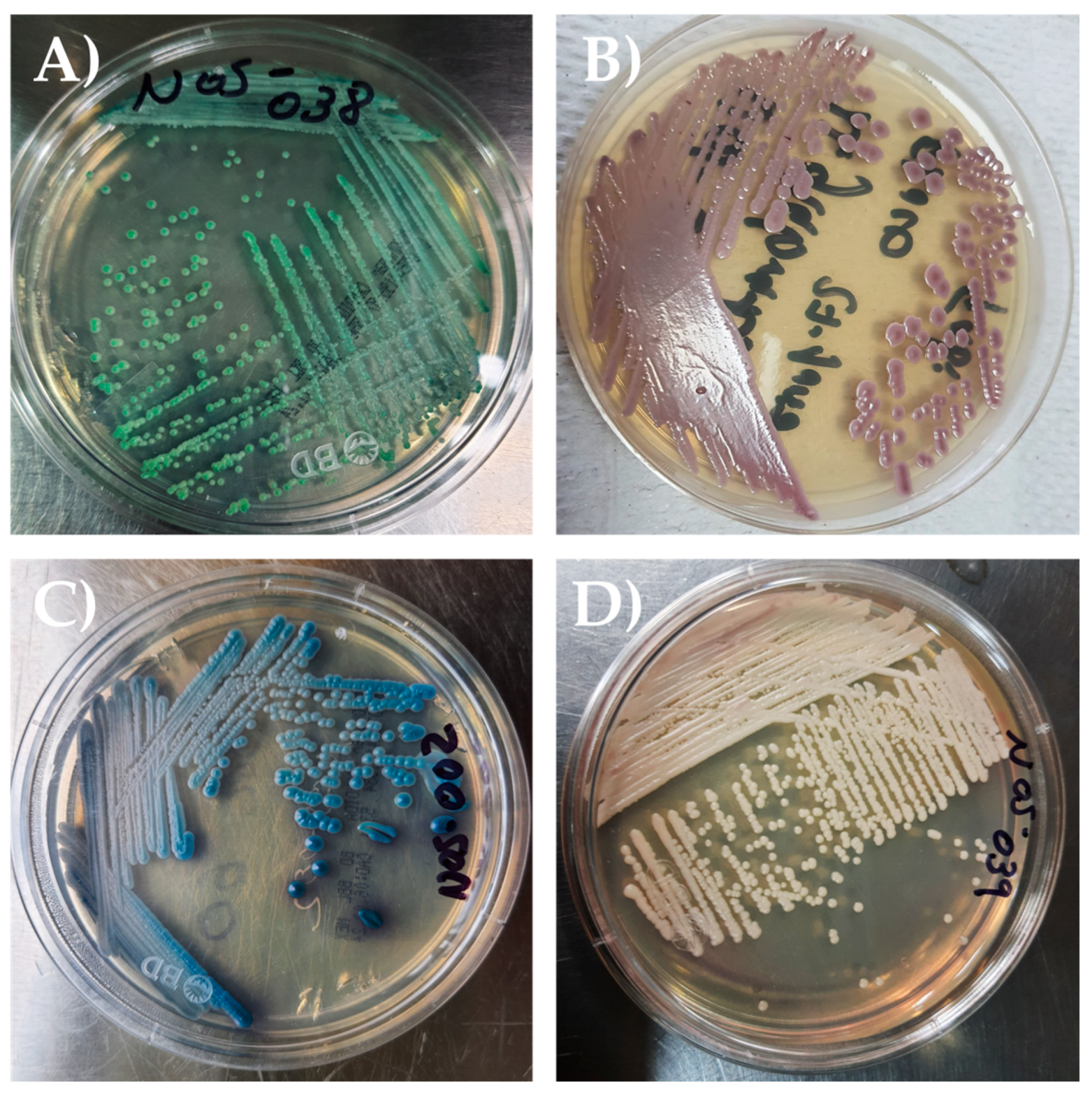

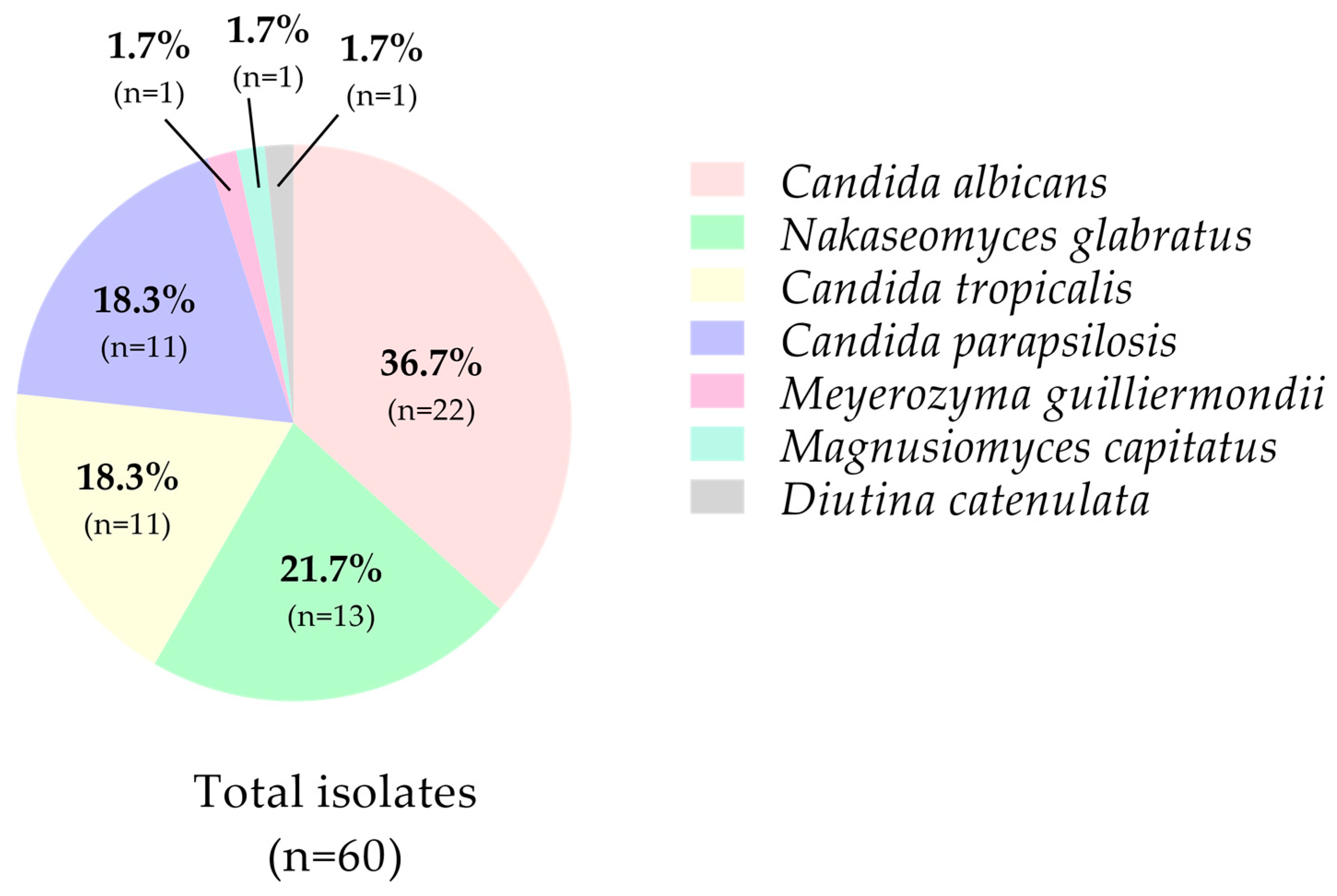

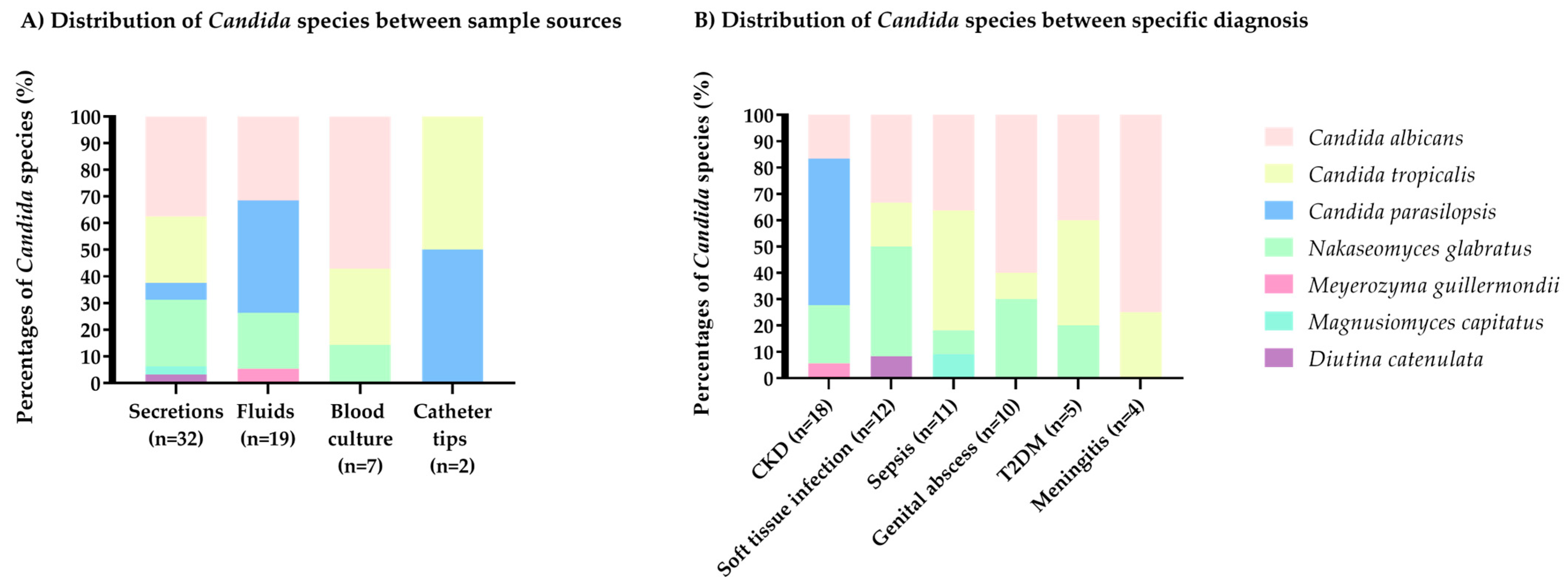

3.2. Phenotypic and Taxonomic Identification of Candida

3.3. Antifungal Susceptibility

3.4. Relative Expression Analysis of Target Genes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 5-FC | 5-fluorocytosine |

| ACT1 | β-actin |

| AMB | Amphotericin B |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| cDNA | Complementary DNA |

| CKD | Chronic Kidney Disease |

| CLSI | Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute |

| DM | Diabetes mellitus |

| DMSO | Dimethyl sulfoxide |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic Acid |

| ERG | Ergosterol |

| FCY1 | Cytosine deaminase |

| FCY2 | Cytosine permease |

| FKS | Fungal Kinetics of Synthesis |

| FLZ | Fluconazole |

| FUR | Phosphoribosyltransferase |

| GM | Geometric Mean |

| h | Hour |

| HCCA | α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid |

| HIV | Human Immunodeficiency Virus |

| I | Intermediate |

| ICU | Intensive Care Unit |

| IMSS | Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social |

| MALDI-TOF MS | Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization Time-Of-Flight Mass Spectrometry |

| MFS | Major Facilitator Superfamily |

| max | maximum |

| MDR | Multidrug resistance |

| MIC | Minimum Inhibitory Concentration |

| min | minimum |

| min. | Minutes |

| MOPS | 3-(N-morpholino)propanesulfonic acid |

| PCR | Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| R | Resistant |

| RNA | Ribonucleic Acid |

| rpm | revolutions per minute |

| RPMI | Roswell Park Memorial Institute |

| S | Susceptible |

| SDB | Sabouraud Dextrose Broth |

| SDD | Susceptible dose-dependent |

| T2DM | Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus |

| URA | Uracil biosynthesis gene |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- El-Ganiny, A.M.; Yossef, N.E.; Kamel, H.A. Prevalence and antifungal drug resistance of nosocomial Candida species isolated from two university hospitals in Egypt. Curr. Med. Mycol. 2021, 7, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Suleyman, G.; Alangaden, G.J. Nosocomial Fungal Infections: Epidemiology, Infection Control, and Prevention. Infect. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 2021, 35, 1027–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poulain, D. Candida albicans, plasticity and pathogenesis. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2015, 41, 208–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horton, M.V.; Holt, A.M.; ENett, J. Mechanisms of pathogenicity for the emerging fungus Candida auris. PLoS Pathog. 2023, 19, e1011843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dadar, M.; Tiwari, R.; Karthik, K.; Chakraborty, S.; Shahali, Y.; Dhama, K. Candida albicans—Biology, molecular characterization, pathogenicity, and advances in diagnosis and control—An update. Microb. Pathog. 2018, 117, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Douglas, A.P.; Stewart, A.G.; Halliday, C.L.; Chen, S.C.-A. Outbreaks of Fungal Infections in Hospitals: Epidemiology, Detection, and Management. J. Fungi 2023, 9, 1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Otto, W.R.; Arendrup, M.C.; Fisher, B.T. A Practical Guide to Antifungal Susceptibility Testing. J. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. Soc. 2023, 12, 214–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pappas, P.G.; Kauffman, C.A.; Andes, D.R.; Clancy, C.J.; Marr, K.A.; Ostrosky-Zeichner, L.; Reboli, A.C.; Schuster, M.G.; Vazquez, J.A.; Walsh, T.J.; et al. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Candidiasis: 2016 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2016, 62, e1–e50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lee, Y.; Puumala, E.; Robbins, N.; Cowen, L.E. Antifungal Drug Resistance: Molecular Mechanisms in Candida albicans and Beyond. Chem. Rev. 2020, 121, 3390–3411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ahmad, S.; Joseph, L.; Parker, J.E.; Asadzadeh, M.; Kelly, S.L.; Meis, J.F.; Khan, Z. ERG6 and ERG2 Are Major Targets Conferring Reduced Susceptibility to Amphotericin B in Clinical Candida glabrata Isolates in Kuwait. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2019, 63, e01900-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Berkow, E.L.; Lockhart, S.R. Fluconazole resistance in Candida species: A current perspective. Infect. Drug Resist. 2017, 10, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sigera, L.S.M.; Denning, D.W. Flucytosine and its clinical usage. Ther. Adv. Infect. Dis. 2023, 10, 20499361231161387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Paul, S.; Singh, S.; Chakrabarti, A.; Rudramurthy, S.M.; Ghosh, A.K. Selection and evaluation of appropriate reference genes for RT-qPCR based expression analysis in Candida tropicalis following azole treatment. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- World Health Organization. WHO Fungal Priority Pathogens List to Guide Research, Development and Public Health Action; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022; 48p. [Google Scholar]

- Jamal, W.; Ahmad, S.; Khan, Z.; Rotimi, V. Comparative evaluation of two matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) systems for the identification of clinically significant yeasts. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2014, 26, 167–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Performance Standards for Antifungal Susceptibility Testing of Yeasts, 3rd ed.; CLSI supplement M27M44S; CLSI: Wayne, PA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Espinel-Ingroff, A.; Cantón, E.; Pemán, J. Antifungal Resistance among Less Prevalent Candida Non-albicans and Other Yeasts versus Established and under Development Agents: A Literature Review. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Performance Standards for Antifungal Susceptibility Testing, 2nd ed.; CLSI document M60; CLSI: Wayne, PA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, S.; Shaw, D.; Joshi, H.; Singh, S.; Chakrabarti, A.; Rudramurthy, S.M.; Ghosh, A.K. Mechanisms of azole antifungal resistance in clinical isolates of Candida tropicalis. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0269721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chomczynski, P. A reagent for the single-step simultaneous isolation of RNA, DNA and proteins from cell and tissue samples. Biotechniques 1993, 15, 532–534, 536–537. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Honey, S.; Futcher, B. A Trizol-Beadbeater RNA extraction method for yeast, and comparison to Novogene RNA extraction. bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Roth, R.; Madhani, H.D.; Garcia, J.F. Total RNA Isolation and Quantification of Specific RNAs in Fission Yeast. Methods Mol. Biol. 2018, 1721, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turan, D.; Habip, Z.; Odabaşı, H.; Dömbekçi, E.; Gündoğuş, N.; Özmen, M.; Aksaray, S. Antifungal Susceptibilities of Rare Yeast Isolates. J. Fungi 2025, 11, 645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- A Pfaller, M.; Diekema, D.J.; Turnidge, J.D.; Castanheira, M.; Jones, R.N. Twenty Years of the SENTRY Antifungal Surveillance Program: Results for Candida Species from 1997–2016. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2019, 6, S79–S94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ourives, A.P.J.; Gonçalves, S.S.; Siqueira, R.A.; Souza, A.C.R.; Canziani, M.E.F.; Manfredi, S.R.; Correa, L.; Colombo, A.L. High rate of Candida deep-seated infection in patients under chronic hemodialysis with extended central venous catheter use. Rev. Iberoam. Micol. 2016, 33, 100–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brescini, L.; Mazzanti, S.; Orsetti, E.; Morroni, G.; Masucci, A.; Pocognoli, A.; Barchiesi, F. Species distribution and antifungal susceptibilities of bloodstream Candida isolates: A nine-years single center survey. J. Chemother. 2020, 32, 244–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pappas, P.G.; Lionakis, M.S.; Arendrup, M.C.; Ostrosky-Zeichner, L.; Kullberg, B.J. Invasive Candidiasis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2018, 4, 18026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kullberg, B.J.; Arendrup, M.C. Invasive Candidiasis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 1445–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lao, M.; Li, C.; Li, J.; Chen, D.; Ding, M.; Gong, Y. Opportunistic invasive fungal disease in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus from Southern China: Clinical features and associated factors. J. Diabetes Investig. 2019, 11, 731–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bays, D.J.; Jenkins, E.N.; Lyman, M.; Chiller, T.; Strong, N.; Ostrosky-Zeichner, L.; Hoenigl, M.; Pappas, P.G.; Thompson, G. Epidemiology of Invasive Candidiasis. Clin. Epidemiol. 2024, 16, 549–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pfaller, M.A.; Diekema, D.J.; Gibbs, D.L.; Newell, V.A.; Ellis, D.J.; Tullio, V.; Rodloff, A.C.; Fu, W.; Ling, T.A. Global Antifungal Surveillance Group. Results from the ARTEMIS DISK Global Antifungal Surveillance Study, 1997 to 2007: A 10.5-Year Analysis of Susceptibilities of Candida Species to Fluconazole and Voriconazole as Determined by CLSI Standardized Disk Diffusion. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2010, 48, 1366–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Nucci, M.; Queiroz-Telles, F.; Tobón, A.M.; Restrepo, A.; Colombo, A.L. Epidemiology of Opportunistic Fungal Infections in Latin America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2010, 51, 561–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corzo-Leon, D.E.; Alvarado-Matute, T.; Colombo, A.L.; Cornejo-Juarez, P.; Cortes, J.; Echevarria, J.I.; Guzman-Blanco, M.; Macias, A.E.; Nucci, M.; Ostrosky-Zeichner, L.; et al. Surveillance of Candida spp Bloodstream Infections: Epidemiological Trends and Risk Factors of Death in Two Mexican Tertiary Care Hospitals. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e97325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Reyes-Montes, M.d.R.; Duarte-Escalante, E.; Martínez-Herrera, E.; Acosta-Altamirano, G.; León, M.G.F.-D. Current status of the etiology of candidiasis in Mexico. Rev. Iberoam. Micol. 2017, 34, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinho, S.; Miranda, I.M.; Costa-De-Oliveira, S. Global Epidemiology of Invasive Infections by Uncommon Candida Species: A Systematic Review. J. Fungi 2024, 10, 558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Siller-Ruiz, M.; Hernández-Egido, S.; Sánchez-Juanes, F.; González-Buitrago, J.M.; Muñoz-Bellido, J.L. Fast methods of fungal and bacterial identification. MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry, chromogenic media. Enferm. Infecc. Microbiol. Clin. 2017, 35, 303–313, (In English and Spanish). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pristov, K.E.; Ghannoum, M.A. Resistance of Candida to azoles and echinocandins worldwide. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2019, 25, 792–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, H.; Zhao, R.; Han, S.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Jia, Z.; Cui, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X. Research progress on the drug resistance mechanisms of Candida tropicalis and future solutions. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1594226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lima, R.; Ribeiro, F.C.; Colombo, A.L.; de Almeida, J.N. The emerging threat antifungal-resistant Candida tropicalis in humans, animals, and environment. Front. Fungal Biol. 2022, 3, 957021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- GonzálEz, G.M.; Elizondo, M.; Ayala, J. Trends in Species Distribution and Susceptibility of Bloodstream Isolates of Candida Collected in Monterrey, Mexico, to Seven Antifungal Agents: Results of a 3-Year (2004 to 2007) Surveillance Study. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2008, 46, 2902–2905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Teixeira, M.V.S.; Aldana-Mejía, J.A.; Ferreira, M.E.d.S.; Furtado, N.A.J.C. Lower Concentrations of Amphotericin B Combined with Ent-Hardwickiic Acid Are Effective against Candida Strains. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- de Almeida, A.A.; Nakamura, S.S.; Fiorini, A.; Grisolia, A.B.; Svidzinski, T.I.E.; de Oliveira, K.M.P. Genotypic variability and antifungal susceptibility of Candida tropicalis isolated from patients with candiduria. Rev. Iberoam. Micol. 2015, 32, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.; Robbins, N.; Cowen, L.E. Molecular mechanisms governing antifungal drug resistance. npj Antimicrob. Resist. 2023, 1, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.T.; Lee, R.E.B.; Barker, K.S.; Lee, R.E.; Wei, L.; Homayouni, R.; Rogers, P.D. Genome-Wide Expression Profiling of the Response to Azole, Polyene, Echinocandin, and Pyrimidine Antifungal Agents in Candida albicans. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2005, 49, 2226–2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, S.; Rong, C.; Li, H.; Wu, Y.; Wu, N.; Chu, Y.; Jiang, N.; Zhang, J.; Shang, H. Genetic microevolution of clinical Candida auris with reduced Amphotericin B sensitivity in China. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2024, 13, 2398596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hull, C.M.; Bader, O.; Parker, J.E.; Weig, M.; Gross, U.; Warrilow, A.G.S.; Kelly, D.E.; Kelly, S.L. Two Clinical Isolates of Candida glabrata Exhibiting Reduced Sensitivity to Amphotericin B Both Harbor Mutations in ERG2. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012, 56, 6417–6421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Liu, Y.; Shu, L.; Zhou, D.; Xie, Y.; Ma, Y.; Kang, M. The prevalence, patterns, and antifungal drug resistance of bloodstream infection-causing fungi in Sichuan Province, China (2019–2023): A retrospective observational study using national monitoring data. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1616013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceballos-Garzon, A.; Peñuela, A.; Valderrama-Beltrán, S.; Vargas-Casanova, Y.; Ariza, B.; Parra-Giraldo, C.M. Emergence and circulation of azole-resistant C. albicans, C. auris and C. parapsilosis bloodstream isolates carrying Y132F, K143R or T220L Erg11p substitutions in Colombia. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1136217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Castanheira, M.; Deshpande, L.M.; Davis, A.P.; Carvalhaes, C.G.; Pfaller, M.A. Azole resistance in Candida glabrata clinical isolates from global surveillance is associated with efflux overexpression. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2022, 29, 371–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czajka, K.M.; Venkataraman, K.; Brabant-Kirwan, D.; Santi, S.A.; Verschoor, C.; Appanna, V.D.; Singh, R.; Saunders, D.P.; Tharmalingam, S. Molecular Mechanisms Associated with Antifungal Resistance in Pathogenic Candida Species. Cells 2023, 12, 2655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yamin, D.; Akanmu, M.H.; Al Mutair, A.; Alhumaid, S.; Rabaan, A.A.; Hajissa, K. Global Prevalence of Antifungal-Resistant Candida parapsilosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2022, 7, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Siqueira, A.C.; Bernardi, G.A.; Arend, L.N.V.S.; Cordeiro, G.T.; Rosolen, D.; Berti, F.C.B.; Ferreira, A.M.M.; Vasconcelos, T.M.; Neves, B.C.; Rodrigues, L.S.; et al. Azole Resistance and ERG11 Mutation in Clinical Isolates of Candida tropicalis. J. Fungi 2025, 11, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Kholy, M.A.; Helaly, G.F.; El Ghazzawi, E.F.; El-Sawaf, G.; Shawky, S.M. Analysis of CDR1 and MDR1 Gene Expression and ERG11 Substitutions in Clinical Candida tropicalis Isolates from Alexandria, Egypt. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2023, 54, 2609–2615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- E Corzo-Leon, D.; Peacock, M.; Rodriguez-Zulueta, P.; Salazar-Tamayo, G.J.; MacCallum, D.M. General hospital outbreak of invasive candidiasis due to azole-resistant Candida parapsilosis associated with an Erg11 Y132F mutation. Med. Mycol. 2020, 59, 664–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wiederhold, N.P. Antifungal Susceptibility Testing: A Primer for Clinicians. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2021, 8, ofab444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Costa, C.; Dias, P.J.; Sá-Correia, I.; Teixeira, M.C. MFS multidrug transporters in pathogenic fungi: Do they have real clinical impact? Front. Physiol. 2014, 5, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pais, P.; Pires, C.; Costa, C.; Okamoto, M.; Chibana, H.; Teixeira, M.C. Membrane Proteomics Analysis of the Candida glabrata Response to 5-Flucytosine: Unveiling the Role and Regulation of the Drug Efflux Transporters CgFlr1 and CgFlr2. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Whaley, S.G.; Berkow, E.L.; Rybak, J.M.; Nishimoto, A.T.; Barker, K.S.; Rogers, P.D. Azole Antifungal Resistance in Candida albicans and Emerging Non-albicans Candida Species. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 2173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ngo, T.M.C.; Santona, A.; Fiamma, M.; Nu, P.A.T.; Do, T.B.T.; Cappuccinelli, P.; Paglietti, B. Azole non-susceptible C. tropicalis and polyclonal spread of C. albicans in Central Vietnam hospitals. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2023, 17, 550–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tosrisawatkasem, O.; Thairat, S.; Tonput, P.; Tantivitayakul, P. Variations in virulence factors, antifungal susceptibility and extracellular polymeric substance compositions of cryptic and uncommon Candida species from oral candidiasis. BMC Oral Health 2025, 25, 1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Delma, F.Z.; Spruijtenburg, B.; Meis, J.F.; de Jong, A.W.; Groot, J.; Rhodes, J.; Melchers, W.J.; Verweij, P.E.; de Groot, T.; Meijer, E.F.; et al. Emergence of Flucytosine-Resistant Candida tropicalis Clade, the Netherlands. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2025, 31, 1354–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dodgson, A.R.; Dodgson, K.J.; Pujol, C.; Pfaller, M.A.; Soll, D.R. Clade-Specific Flucytosine Resistance Is Due to a Single Nucleotide Change in the FUR1 Gene of Candida albicans. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2004, 48, 2223–2227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| n = 55 | |

|---|---|

| Male gender, n (%) | 34 (61.8) |

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 59 ± 14 |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean ± SD | 27.6 ± 5.0 |

| Comorbidities | |

| T2DM, n (%) | 22 (40.0) |

| CKD, n (%) | 14 (25.5) |

| CKD + T2DM, n (%) | 8 (14.5) |

| Negative, n (%) | 11 (20.0) |

| Hospital service requesting culture | |

| Internal Medicine, n (%) | 25 (45.5) |

| Nephrology, n (%) | 17 (30.9) |

| General Surgery, n (%) | 9 (16.4) |

| Gynecology, n (%) | 4 (7.3) |

| Sample source | |

| Secretions 1, n (%) | 27 (49.1) |

| Fluids 2, n (%) | 19 (34.5) |

| Blood culture, n (%) | 7 (12.7) |

| Catheter tips, n (%) | 2 (3.6) |

| Specific diagnosis | |

| CKD, n (%) | 18 (32.7) |

| Soft tissue infection, n (%) | 10 (18.2) |

| Sepsis, n (%) | 10 (18.2) |

| Genital abscess, n (%) | 8 (14.5) |

| T2DM, n (%) | 5 (9.1) |

| Meningitis, n (%) | 4 (7.3) |

| Antifungal Agent | Range (Min–Max) | GM MIC (µg/mL) | MIC50 | MIC90 | Resistant Isolates (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S | SSD | I | R | |||||

| Candida albicans, (n = 22) | ||||||||

| Amphotericin B (AMB) | 0.5–16.0 | 1.3 | 2.0 | 16.0 | 17 (77.3) | - | - | 5 (22.7) |

| Fluconazole (FLZ) | 2.0–64.0 | 33.0 | 64.0 | 64.0 | 1 (4.5) | 1 (4.5) | - | 20 (90.9) |

| 5-Flucytosine (5-FC) | 0.125–4.0 | 0.20 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 22 (100.0) | - | - | 0 (0) |

| Candida tropicalis, (n = 11) | ||||||||

| Amphotericin B (AMB) | 0.5–16.0 | 3.8 | 2.0 | 16.0 | 4 (36.4) | - | - | 7 (63.9) |

| Fluconazole (FLZ) | 0.5–64.0 | 26.5 | 64.0 | 64.0 | 1 (9.1) | 0 (0) | - | 10 (90.9) |

| 5-Flucytosine (5-FC) | 0.125–2.0 | 0.3 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 11 (100.0) | - | - | 0 (0) |

| Candida parapsilosis, (n = 11) | ||||||||

| Amphotericin B (AMB) | 1.0–4.0 | 1.7 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 4 (36.4) | - | - | 7 (63.9) |

| Fluconazole (FLZ) | 1.0–4.0 | 2.3 | 2.0 | 4.0 | 8 (72.7) | 3 (27.3) | - | 0 (0) |

| 5-Flucytosine (5-FC) | 0.125–0.5 | 0.2 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 11 (100.0) | - | - | 0 (0) |

| Nakaseomyces glabratus, (n = 13) | ||||||||

| Amphotericin B (AMB) | 1.0–8.0 | 1.8 | 1.0 | 8.0 | 7 (53.8) | - | - | 6 (46.2) |

| Fluconazole (FLZ) | 8.0–64.0 | 30.3 | 32.0 | 64.0 | 0 (0) | 7 (53.8) | - | 6 (46.2) |

| 5-Flucytosine (5-FC) | 0.125–0.5 | 0.1 | 0.125 | 0.125 | 13 (100.0) | - | - | 0 (0) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hernandez-Reyes, F.B.; Muñoz-Miranda, L.A.; Kirchmayr, M.R.; Ortiz-Lazareno, P.C.; Cortés-Zárate, R.; Iñiguez-Moreno, M.; Jacobo-Cuevas, H.; Nava-Valdivia, C.A. Antifungal Susceptibility and Resistance-Associated Gene Expression in Nosocomial Candida Isolates. J. Fungi 2025, 11, 895. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof11120895

Hernandez-Reyes FB, Muñoz-Miranda LA, Kirchmayr MR, Ortiz-Lazareno PC, Cortés-Zárate R, Iñiguez-Moreno M, Jacobo-Cuevas H, Nava-Valdivia CA. Antifungal Susceptibility and Resistance-Associated Gene Expression in Nosocomial Candida Isolates. Journal of Fungi. 2025; 11(12):895. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof11120895

Chicago/Turabian StyleHernandez-Reyes, Fabiola Berenice, Luis Alfonso Muñoz-Miranda, Manuel R. Kirchmayr, Pablo César Ortiz-Lazareno, Rafael Cortés-Zárate, Maricarmen Iñiguez-Moreno, Heriberto Jacobo-Cuevas, and Cesar Arturo Nava-Valdivia. 2025. "Antifungal Susceptibility and Resistance-Associated Gene Expression in Nosocomial Candida Isolates" Journal of Fungi 11, no. 12: 895. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof11120895

APA StyleHernandez-Reyes, F. B., Muñoz-Miranda, L. A., Kirchmayr, M. R., Ortiz-Lazareno, P. C., Cortés-Zárate, R., Iñiguez-Moreno, M., Jacobo-Cuevas, H., & Nava-Valdivia, C. A. (2025). Antifungal Susceptibility and Resistance-Associated Gene Expression in Nosocomial Candida Isolates. Journal of Fungi, 11(12), 895. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof11120895