Extracts of the Algerian Fungus Phlegmacium herculeum: Chemical Analysis, Antioxidant, Antibacterial, and Cytotoxicity Evaluation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection and Identification

2.2. Preparation of Extracts of Phlegmacium herculeum

2.3. SPME–GC–MS Analysis of Volatile Compounds

2.4. NMR and GC–MS Characterization of Crude Extracts

2.5. Antioxidant Assay

2.6. Antibacterial Assay

2.7. Cytotoxicity Assay

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

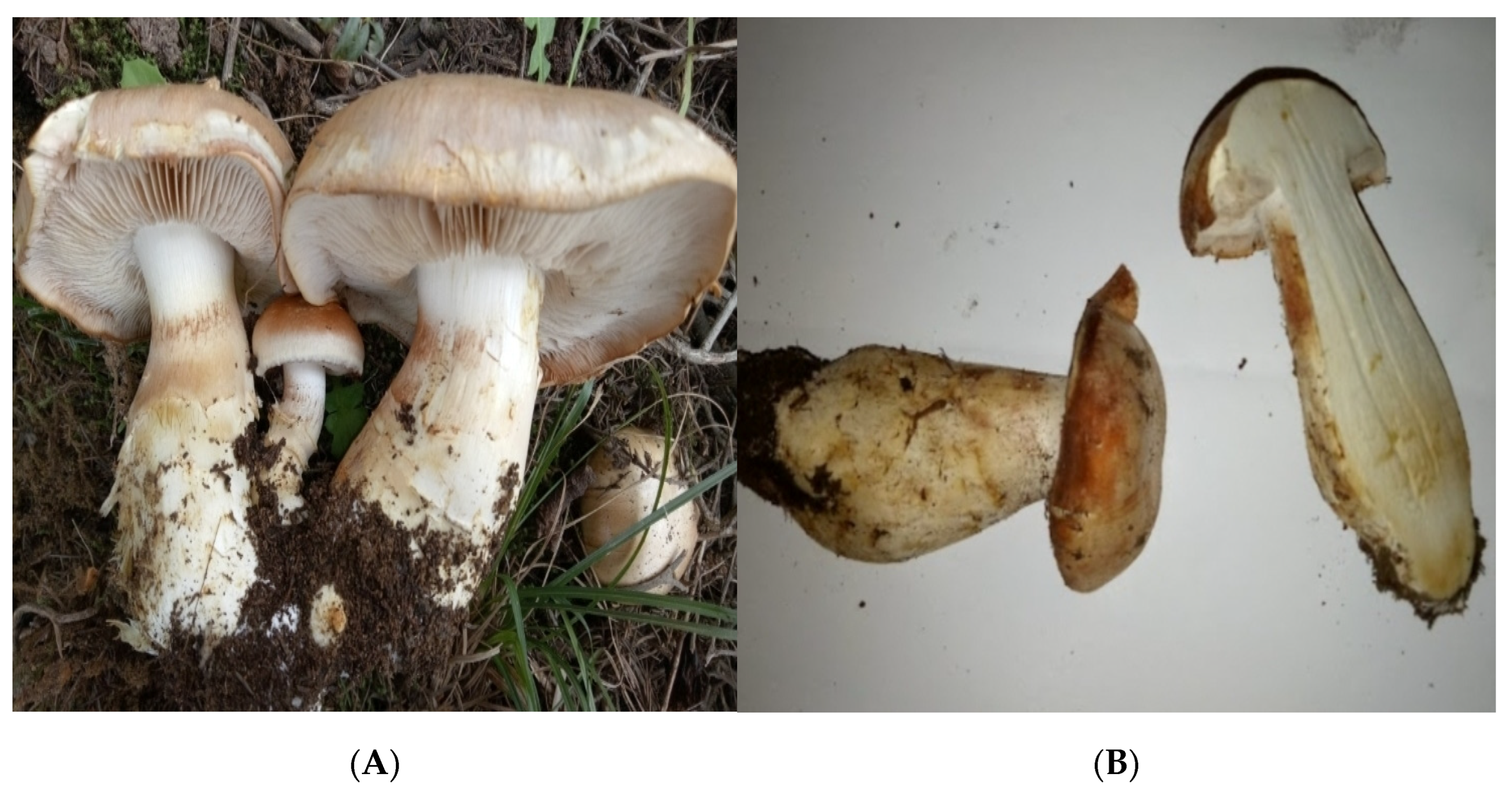

3.1. Morphological, Molecular, and Taxonomic Description of the Macrofungus

3.2. Analysis of Volatile Compounds by SPME–GC–MS

3.3. Characterization of the Crude Extracts

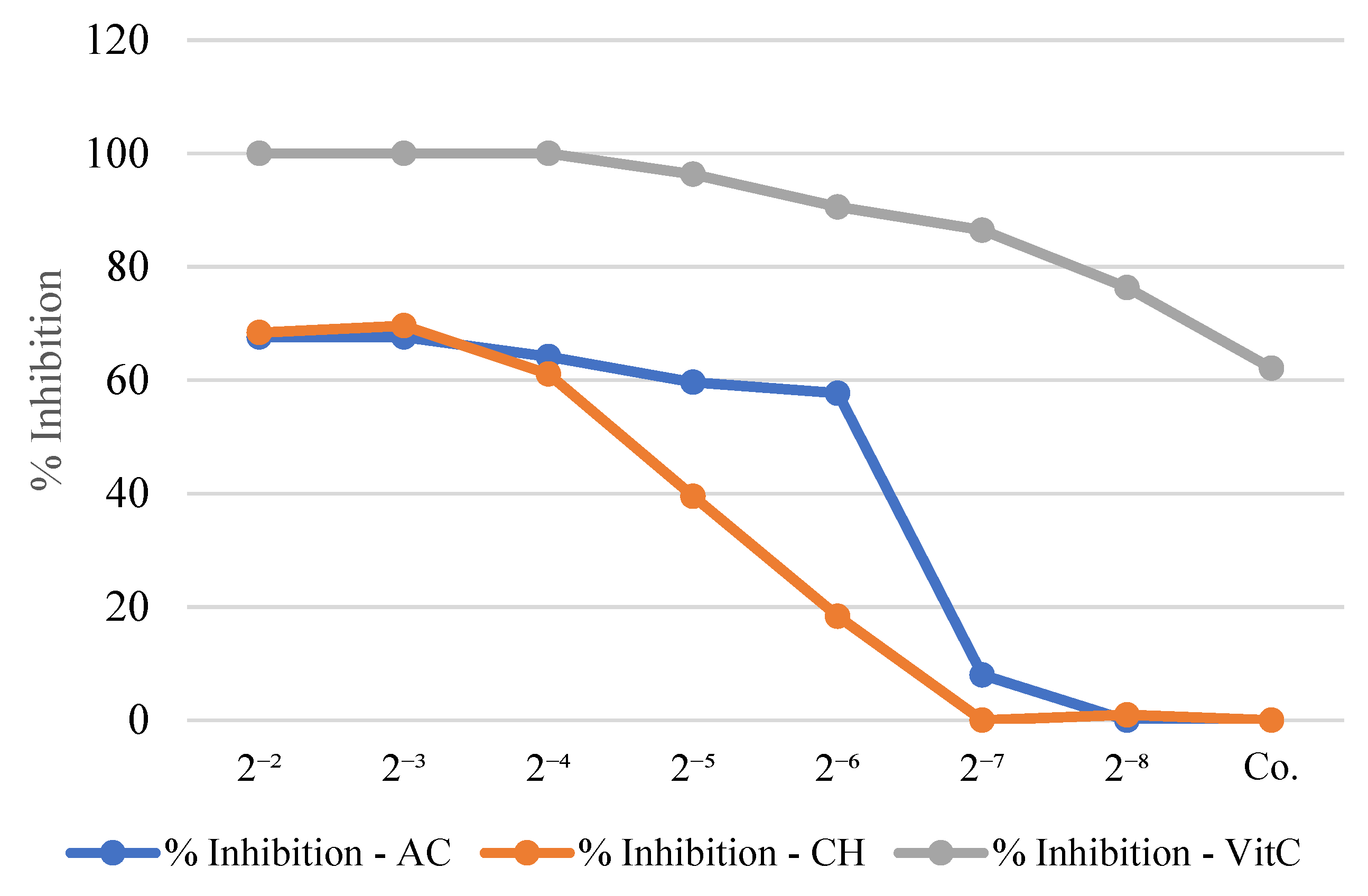

3.4. Antioxidant Activity

3.5. Antibacterial Activity

3.6. Cytotoxicity Activity

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| P.herculeum | Phlegmacium herculeum |

| CHCl3, CH | Chloroform |

| EtOAc, AC | Ethyl acetate |

| VitC | Vitamin C |

| Co. | Concentration |

References

- Bills, G.F.; Gloer, J.B. Biologically active secondary metabolites from the fungi. Microbiol. Spectr. 2016, 4, 10–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zatout, R. Potential Bio-Control Substances Produced by Fungi and Plants of Different Mediterranean Basin Ecosystems. Doctoral Dissertation, Université Frères Mentouri-Constantine 1, Constantine, Algeria, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Salwan, R.; Katoch, S.; Sharma, V. Recent developments in shiitake mushrooms and their nutraceutical importance. In Fungi in Sustainable Food Production; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 165–180. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, X.; Shi, Y.; Shi, D.; Tu, Y.; Liu, L. Biological activities of secondary metabolites from the edible-medicinal macrofungi. J. Fungi 2024, 10, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diagne, N.; Ngom, M.; Djighaly, P.I.; Fall, D.; Hocher, V.; Svistoonoff, S. Roles of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi on plant growth and performance: Importance in biotic and abiotic stressed regulation. Diversity 2020, 12, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Cartabia, A.; Lalaymia, I.; Declerck, S. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and production of secondary metabolites in medicinal plants. Mycorrhiza 2022, 32, 221–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, Y.; Shah, S.; Tian, H. The roles of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in influencing plant nutrients, photosynthesis, and metabolites of cereal crops—A review. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liimatainen, K.; Niskanen, T.; Dima, B.; Kytövuori, I.; Ammirati, J.F.; Frøslev, T.G. The largest type study of Agaricales species to date: Bringing identification and nomenclature of Phlegmacium (Cortinarius) into the DNA era. Persoonia 2014, 33, 98–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mrak, T.; Brailey-Crane, P.A.; Šibanc, N.; Martinović, T.; Gričar, J.; Kraigher, H. Mycelial communities associated with Ostrya carpinifolia, Quercus pubescens and Pinus nigra in a patchy Sub-Mediterranean Karst woodland. Mycorrhiza 2025, 35, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesfek, F.; Fortas, Z.; Dib, S. Inventory and ecology of macrofungi and plants in a North-Western Algerian forest. J. Biodivers. Conserv. Bioresour. Manag. 2021, 7, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ait Hamadouche, Y.; Soulef, D.I.B.; Mechouet, O. Mycochemical contents of higher fungi and their in vitro effect on plant growth. Not. Bot. Horti Agrobot. Cluj-Napoca 2024, 52, 13358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zatout, R.; Cimmino, A.; Cherfia, R.; Chaouche, N.K. Isolation of tyrosol the main phytotoxic metabolite produced by the edible fungus Agaricus litoralis. Egypt. J. Chem. 2021, 64, 5741–5745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minerdi, D.; Maggini, V.; Fani, R. Volatile organic compounds: From figurants to leading actors in fungal symbiosis. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2021, 97, fiab067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Jaddaoui, I.; Rangel, D.E.; Bennett, J.W. Fungal volatiles have physiological properties. Fungal Biol. 2023, 127, 1231–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Effmert, U.; Kalderás, J.; Warnke, R.; Piechulla, B. Volatile mediated interactions between bacteria and fungi in the soil. J. Chem. Ecol. 2012, 38, 665–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, R.; Lee, S.; Bennett, J.W. Fungal volatile organic compounds and their role in ecosystems. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 99, 3395–3405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heleno, S.A.; Martins, A.; Queiroz, M.J.R.; Ferreira, I.C. Bioactivity of phenolic acids: Metabolites versus parent compounds: A review. Food Chem. 2015, 173, 501–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Peng, Q.; Xu, X.; Shi, B.; Qiao, Y. Antioxidant capacities and non-volatile metabolites changes after solid-state fermentation of soybean using oyster mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus) mycelium. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1509341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sureshkumar, S.; Merlin, I.; Prasai, J.R.; Rajapriya, P.; Pandi, M. Antioxidant, antibacterial, cytotoxicity, and phytochemical potentials of fungal bioactive secondary metabolites. J. Basic Microbiol. 2022, 62, 1379–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadhwa, K.; Kapoor, N.; Kaur, H.; Abu-Seer, E.A.; Tariq, M.; Siddiqui, S.; Alghamdi, S. A comprehensive review of the diversity of fungal secondary metabolites and their emerging applications in healthcare and environment. Mycobiology 2024, 52, 335–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattarai, K.; Kabir, M.E.; Bastola, R.; Baral, B. Fungal natural products galaxy: Biochemistry and molecular genetics toward blockbuster drugs discovery. Adv. Genet. 2021, 107, 193–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zatout, R.; Christopher, B.; Cherfia, R.; Chaoua, S.; Chaouche, N.K. A new record of Agaricus litoralis, a rare edible macro-fungus from Eastern Algeria. Mycopath 2023, 20, 51–56. [Google Scholar]

- Bon, M. Guía de Campo de los Hongos de Europa; Omega: Barcelona, Spain, 1987; 368p. [Google Scholar]

- Zatout, R.; Benslama, O.; Makhlouf, F.Z.; Cimmino, A.; Salvatore, M.M.; Andolfi, A.; Masi, M. Exploring the potential of Genista ulicina phytochemicals as natural biocontrol agents: A comparative in vitro and in silico analysis. Toxins 2025, 17, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zatout, R.; Kacem Chaouche, N. Antibacterial activity screening of an edible mushroom Agaricus litoralis. Int. J. Bot. Stud. 2023, 8, 49–52. [Google Scholar]

- Salvatore, M.M.; Pappalardo, C.; Suarez, E.G.P.; Salvatore, F.; Andolfi, A.; Gesuele, R.; Galdiero, E.; Libralato, G.; Guida, M.; Siciliano, A. Ecotoxicological and metabolomic investigation of chronic exposure of Daphnia magna (Straus, 1820) to yttrium environmental concentrations. Aquat. Toxicol. 2024, 276, 107117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blois, M.S. Antioxidant determinations by the use of a stable free radical. Nature 1958, 181, 1199–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand-Williams, W.; Cuvelier, M.E.; Berset, C.L.W.T. Use of a free radical method to evaluate antioxidant activity. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 1995, 28, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balouiri, M.; Sadiki, M.; Ibnsouda, S.K. Methods for in vitro evaluating antimicrobial activity: A review. J. Pharm. Anal. 2016, 6, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Amor, A.; Hemmami, H.; Gherbi, M.T.; Seghir, B.B.; Zeghoud, S.; Gharbi, A.H.; Barhoum, A. Synthesis of spherical carbon nanoparticles from orange peel and their surface modification with chitosan: Evaluation of optical properties, biocompatibility, antioxidant and anti-hemolytic activity. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 2025, 15, 11345–11358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liimatainen, K.; Kim, J.T.; Pokorny, L.; Kirk, P.M.; Dentinger, B.; Niskanen, T. Taming the beast: A revised classification of Cortinariaceae based on genomic data. Fungal Divers. 2022, 112, 89–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Høiland, K.; Danielsen, J.S.; Gulden, G.; Marthinsen, G.; Tjessem, I.V. Web caps Cortinarius and Phlegmacium (Agaricales, Cortinariaceae) in Svalbard and on Bear Island. AGARICA 2025, 45, 1–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, O.; Crespo, A.; Divakar, P.K.; Elix, J.A.; Lumbsch, H.T. Molecular phylogeny of parmotremoid lichens (Ascomycota, Parmeliaceae). Mycologia 2005, 97, 150–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, I.; Lavega González, R.; Tejedor-Calvo, E.; Pérez Clavijo, M.; Carrasco, J. Odor profile of four cultivated and freeze-dried edible mushrooms by using sensory panel, electronic nose and GC-MS. J. Fungi 2022, 8, 953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, G.; Li, J.; Liu, H.; Wang, Y. Volatile compounds and aroma characteristics of mushrooms: A review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 64, 13175–13192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, A.; Venâncio, A. The potential of fatty acids and their derivatives as antifungal agents: A review. Toxins 2022, 14, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, R.; Liang, Z.Q.; Wang, Y.; Zeng, N.K. Analysis of aromatic components of two edible mushrooms, Phlebopus portentosus and Cantharellus yunnanensis using HS-SPME/GC-MS. Results Chem. 2022, 4, 100282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitajima, S.; Maruyama, Y.; Kuroda, M. Volatile short-chain aliphatic aldehydes act as taste modulators through the orally expressed calcium-sensing receptor CaSR. Molecules 2023, 28, 4585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aisala, H.; Manninen, H.; Laaksonen, T.; Linderborg, K.M.; Myoda, T.; Hopia, A.; Sandell, M. Linking volatile and non-volatile compounds to sensory profiles and consumer liking of wild edible Nordic mushrooms. Food Chem. 2020, 304, 125403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ladygina, N.; Dedyukhina, E.G.; Vainshtein, M.B. A review on microbial synthesis of hydrocarbons. Process Biochem. 2006, 41, 1001–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farré-Armengol, G.; Filella, I.; Llusià, J.; Peñuelas, J. β-Ocimene, a key floral and foliar volatile involved in multiple interactions between plants and other organisms. Molecules 2017, 22, 1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, W.; Ji, X. Comparative analysis of volatile terpenes and terpenoids in the leaves of Pinus species—A potentially abundant renewable resource. Molecules 2021, 26, 5244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathna, J.; Bakkiyaraj, D.; Pandian, S.K. Anti-biofilm mechanisms of 3,5-di-tert-butylphenol against clinically relevant fungal pathogens. Biofouling 2016, 32, 979–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Wang, P.; Lucardi, R.D.; Su, Z.; Li, S. Natural sources and bioactivities of 2,4-di-tert-butylphenol and its analogs. Toxins 2020, 12, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duc, N.H.; Vo, H.T.; van Doan, C.; Hamow, K.A.; Le, K.H.; Posta, K. Volatile organic compounds shape belowground plant–fungi interactions. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1046685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rocco, M.; Kammer, J.; Santonja, M.; Temime-Roussel, B.; Saignol, C.; Lecareux, C.; Ormeño, E. Is litter biomass a driver of soil volatile organic compound fluxes in Mediterranean forest? Biogeosciences 2025, 22, 3661–3680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.; Lee, B.; Park, J.; Kim, H.J.; Cheong, H. Comparative antioxidant activity and structural feature of protocatechuic acid and phenolic acid derivatives by DPPH and intracellular ROS. Lett. Drug Des. Discov. 2018, 15, 612–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gülcin, I. Antioxidant activity of food constituents: An overview. Arch. Toxicol. 2012, 86, 345–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczepańska, P.; Rychlicka, M.; Groborz, S.; Kruszyńska, A.; Ledesma-Amaro, R.; Rapak, A.; Lazar, Z. Studies on the anticancer and antioxidant activities of resveratrol and long-chain fatty acid esters. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 7167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heer, A.; Guleria, S.; Razdan, V.K. Chemical composition, antioxidant and antimicrobial activities and characterization of bioactive compounds from essential oil of Cinnamomum tamala grown in north-western Himalaya. J. Plant Biochem. Biotechnol. 2017, 26, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemzadeh, A.; Jaafar, H.Z.; Rahmat, A. Antioxidant activities, total phenolics and flavonoids content in two varieties of Malaysia young ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe). Molecules 2010, 15, 4324–4333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zatout, R.; Benarbia, R.; Yalla, I. Phytochemical profiles and antimicrobial activities of Phellinus mushroom: Implications for agricultural health and crop protection. Agric. Res. J. 2024, 61, 340–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, I.C.; Barros, L.; Abreu, R. Antioxidants in wild mushrooms. Curr. Med. Chem. 2009, 16, 1543–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burt, S. Essential oils: Their antibacterial properties and potential applications in foods—A review. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2004, 94, 223–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stephane, F.F.Y. Terpenoids as Important Bioactive Constituents of Essential Oils. In Essential Oils: Bioactive Compounds, New Perspectives and Applications; Intechopen: London, UK, 2020; Volume 75. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, J.Y.; Moon, J.H.; Seong, K.Y.; Park, K.H. Antimicrobial activity of 4-hydroxybenzoic acid and trans 4-hydroxycinnamic acid isolated and identified from rice hull. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 1998, 62, 2273–2276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez–Maldonado, A.F.; Schieber, A.; Gänzle, M.G. Structure–function relationships of the antibacterial activity of phenolic acids and their metabolism by lactic acid bacteria. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2011, 111, 1176–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borges, A.; Ferreira, C.; Saavedra, M.J.; Simões, M. Antibacterial activity and mode of action of ferulic and gallic acids against pathogenic bacteria. Microb. Drug Resist. 2013, 19, 256–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, M.J.; Ferreira, I.C.; Dias, J.; Teixeira, V.; Martins, A.; Pintado, M. A review on antimicrobial activity of mushroom (Basidiomycetes) extracts and isolated compounds. Planta Medica 2012, 78, 1707–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, S.; Li, L.; Yu, C.; Peng, F. Natural products’ antiangiogenic roles in gynecological cancer. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1353056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oraibi, A.I.; Dawood, A.H.; Trabelsi, G.; Mahamat, O.B.; Chekir-Ghedira, L.; Kilani-Jaziri, S. Antioxidant activity and selective cytotoxicity in HCT-116 and WI-38 cell lines of LC-MS/MS profiled extract from Capparis spinosa L. Front. Chem. 2025, 13, 1540174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virtanen, S.S.; Kukkonen-Macchi, A.; Vainio, M.; Elima, K.; Härkönen, P.L.; Jalkanen, S.; Yegutkin, G.G. Adenosine inhibits tumor cell invasion via receptor-independent mechanisms. Mol. Cancer Res. 2014, 12, 1863–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J.; Zhao, Z.; Suo, H.; Paraghamian, S.E.; Hawkins, G.M.; Sun, W.; Bae-Jump, V. Linoleic acid exhibits anti-proliferative and anti-invasive activities in endometrial cancer cells and a transgenic model of endometrial cancer. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2024, 25, 2325130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dongdong, Z.; Jin, Y.; Yang, T.; Yang, Q.; Wu, B.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, F. Antiproliferative and immunoregulatory effects of azelaic acid against acute myeloid leukemia via the activation of notch signaling pathway. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| N. | Component 1 | LRIcalc 2 | LRIlit 3 | Area % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Butanal | 568 | 570 | 3.8 |

| 2 | 3-Methylbutanal | 631 | 629 | 7.2 |

| 3 | 2-Methylbutanal | 638 | 639 | 8.0 |

| 4 | Pentanal | 672 | 696 | 0.5 |

| 5 | 3-Methylbutanoic acid | 835 | 839 | 10.5 |

| 6 | 3,5-Dimethyloctane | 922 | 928 | 1.4 |

| 7 | 3-Methylpentanoic acid | 938 | 941 | 12.6 |

| 8 | Limonene | 1021 | 1029 | 1.6 |

| 9 | 1,8-Cineole | 1035 | 1033 | 1.2 |

| 10 | cis-β-Ocimene | 1040 | 1037 | 6.4 |

| 11 | 2-Methyldecane | 1062 | 1059 | 1.1 |

| 12 | Dodecane | 1210 | 1214 | 1.9 |

| 14 | Propanedioic acid, propyl- | 1259 | 1266 | 17.5 |

| 13 | 2,3,5,8-Tetramethyldecane | 1315 | 1318 | 3.3 |

| 16 | Farnesan | 1378 | 1381 | 1.9 |

| 15 | trans-1,10-Dimethyl-trans-9-decalinol | 1418 | 1423 | 5.1 |

| 17 | 2(4H)-Benzofuranone, 5,6,7,7a-tetrahydro-4,4,7a-trimethyl- | 1521 | 1525 | 2.6 |

| 18 | Elemol | 1537 | 1543 | 1.7 |

| 19 | Hexadecane | 1610 | 1612 | 1.6 |

| 20 | Nonadecane | 1907 | 1910 | 7.8 |

| 21 | 3,5-Di-tert-butylphenol | 2314 | 2310 | 2.3 |

| SUM | 100.0 | |||

| Monoterpenes | 8.0 | |||

| Monoterpenoids | 1.2 | |||

| Sesquiterpenes | 1.9 | |||

| Sesquiterpenoids | 6.8 | |||

| Aldehydes | 19.5 | |||

| Fatty acids | 23.1 | |||

| Hydrocarbons | 17.1 | |||

| Phenols | 2.3 | |||

| Others | 20.1 |

| Compound | LRI | Area % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CHCl3 Extract | EtOAc Extract | ||

| Lactic Acid, 2TMS | 1066 | 4.61 | |

| β-Lactate 2TMS | 1157 | 0.66 | |

| 3-Hydroxyisobutyric acid, 2TMS | 1173 | 2.32 | |

| Benzoic Acid, TMS | 1252 | 0.87 | |

| Glycerol, 3TMS | 1281 | 2.25 | 19.37 |

| Phenylacetic acid, TMS | 1308 | 4.25 | 1.46 |

| Succinic acid, 2TMS | 1315 | 0.55 | 17.18 |

| Fumaric acid, 2TMS | 1353 | 4.50 | |

| Pimelic acid, 2TMS | 1604 | 1.20 | |

| 4-Hydroxybenzoic acid, 2TMS | 1635 | 3.29 | |

| 4-Hydroxyphenylacetic acid, 2TMS | 1646 | 1.41 | |

| Suberic acid, 2TMS | 1695 | 1.05 | 7.74 |

| Azelaic acid, 2TMS | 1799 | 17.72 | 18.82 |

| Protocatechoic acid, 3TMS | 1829 | 1.12 | |

| Sebacic acid, 2TMS | 1899 | 1.43 | |

| Palmitic acid, TMS | 2042 | 15.07 | |

| Linoleic acid, TMS | 2214 | 46.85 | |

| Uridine, 3TMS | 2487 | 3.29 | |

| 9,18-Dihydroxyoctadecanoic acid, 3TMS | 2533 | 2.12 | |

| 9,12,13-Trihydroxyoctadec-15-enoic acid, 4TMS | 2643 | 7.83 | |

| Adenosine, 4TMS | 2669 | 13.03 | |

| Inhibition Zones (mm) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Bacterial Strain | CHCl3 Extract | EtOAc Extract |

| Escherichia coli (NCTC 10538) | 10 ± 0.5 | 18 ± 0.7 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa (NCIMB 8626) | 9 ± 0.4 | 13 ± 0.6 |

| Bacillus spizizenii (ATCC 6633) | - | - |

| Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC 6538) | 18 ± 0.8 | 11 ± 0.5 |

| CHCl3 | EtOAc | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concentration (mg/mL) | Viability (%) | Mortality (%) | Viability (%) | Mortality (%) |

| 8 | 100% | 0% | 90% | 10% |

| 4 | 100% | 0% | 100% | 0% |

| 2 | 100% | 0% | 100% | 0% |

| 1 | 100% | 0% | 100% | 0% |

| 0.5 | 100% | 0% | 100% | 0% |

| 0.25 | 100% | 0% | 100% | 0% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zatout, R.; Garzoli, S.; Khodja, L.Y.; Abdelaziz, O.; Salvatore, M.M.; Andolfi, A.; Masi, M.; Cimmino, A. Extracts of the Algerian Fungus Phlegmacium herculeum: Chemical Analysis, Antioxidant, Antibacterial, and Cytotoxicity Evaluation. J. Fungi 2025, 11, 894. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof11120894

Zatout R, Garzoli S, Khodja LY, Abdelaziz O, Salvatore MM, Andolfi A, Masi M, Cimmino A. Extracts of the Algerian Fungus Phlegmacium herculeum: Chemical Analysis, Antioxidant, Antibacterial, and Cytotoxicity Evaluation. Journal of Fungi. 2025; 11(12):894. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof11120894

Chicago/Turabian StyleZatout, Roukia, Stefania Garzoli, Lounis Youcef Khodja, Ouided Abdelaziz, Maria Michela Salvatore, Anna Andolfi, Marco Masi, and Alessio Cimmino. 2025. "Extracts of the Algerian Fungus Phlegmacium herculeum: Chemical Analysis, Antioxidant, Antibacterial, and Cytotoxicity Evaluation" Journal of Fungi 11, no. 12: 894. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof11120894

APA StyleZatout, R., Garzoli, S., Khodja, L. Y., Abdelaziz, O., Salvatore, M. M., Andolfi, A., Masi, M., & Cimmino, A. (2025). Extracts of the Algerian Fungus Phlegmacium herculeum: Chemical Analysis, Antioxidant, Antibacterial, and Cytotoxicity Evaluation. Journal of Fungi, 11(12), 894. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof11120894