Mycobiomes of Six Lichen Species from the Russian Subarctic: A Culture-Independent Analysis and Cultivation Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Sites and Sample Collection

2.2. Preparing Samples for Inoculation onto Agarised Culture Media

2.3. Preparation of Samples, DNA Extraction, Amplification, and Sequencing

2.3.1. DNA Extraction from Lichen Thalli

2.3.2. DNA Extraction from Pure Cultures

2.3.3. Processing of Nephromopsis nivalis Thalli to Remove Epiphytic Propagules

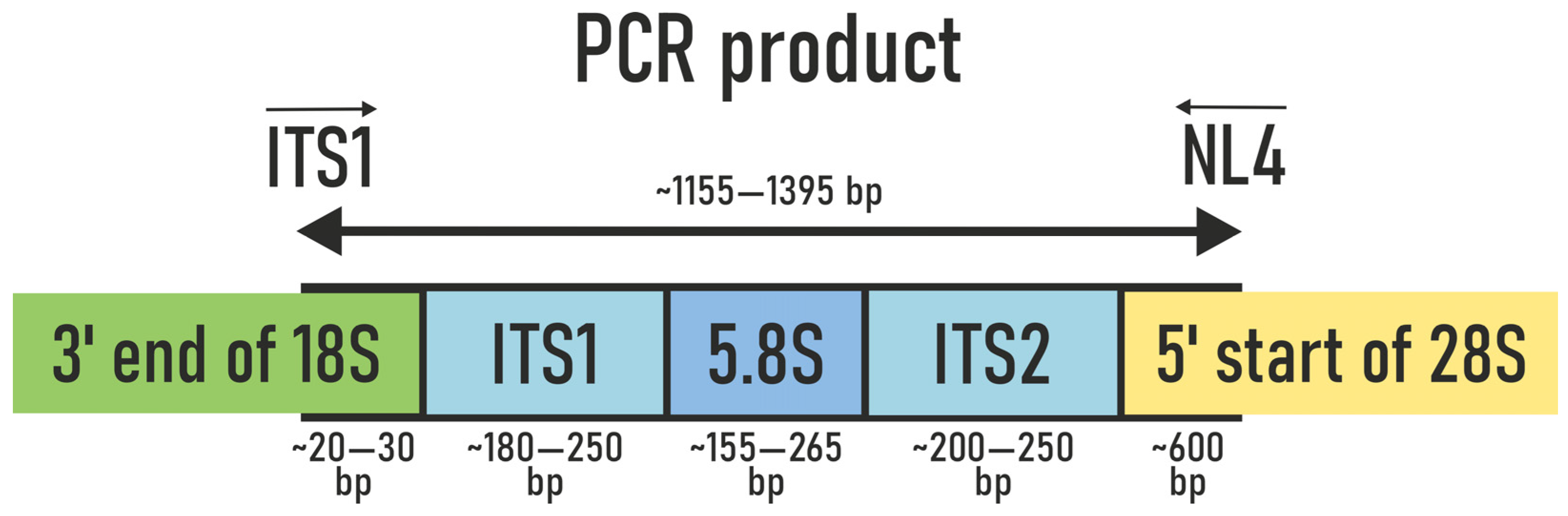

2.3.4. The Process of Obtaining Amplicons for the Analysis of Pure Fungal Cultures via PCR

2.3.5. Electrophoresis of Genomic DNA and PCR Products

2.3.6. Preparing PCR Products for Sanger Sequencing

2.3.7. Sanger Sequencing

2.3.8. NGS Sequencing and Identification of OTUs

2.4. Calculation of Colony-Forming Units (CFU) per Gram of Dry Sample

2.5. Determination of Alpha Diversity Indices

2.6. Light Microscopy

2.7. Statistical Analysis and Visualisation

2.8. Deposition of Sequences of Pure Cultures and Illumina NGS Sequences

3. Results

3.1. Identification of Mycobionts

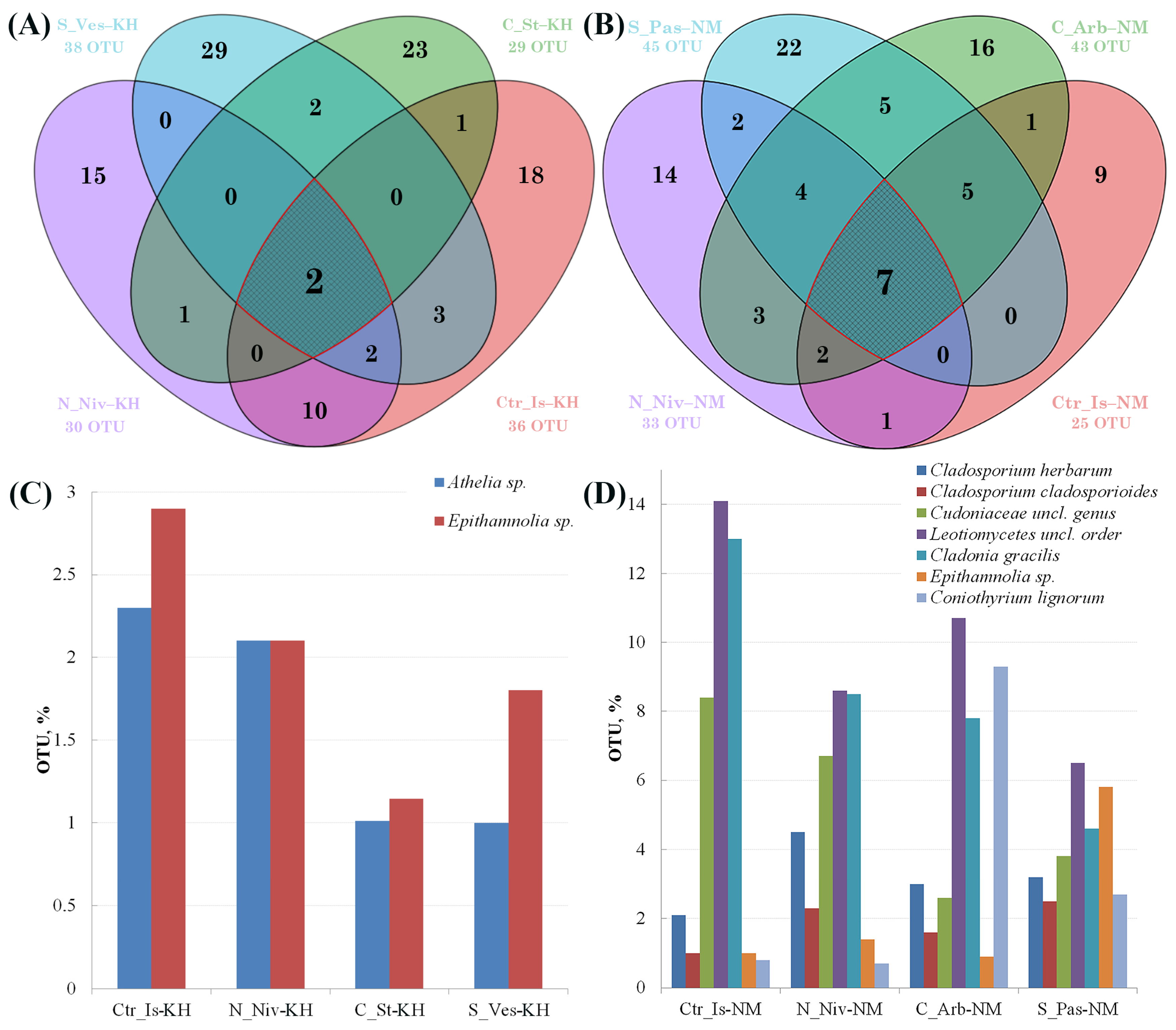

3.2. OTU Analysis

3.3. Analysis of Mycobiome Structure Using High-Throughput Sequencing

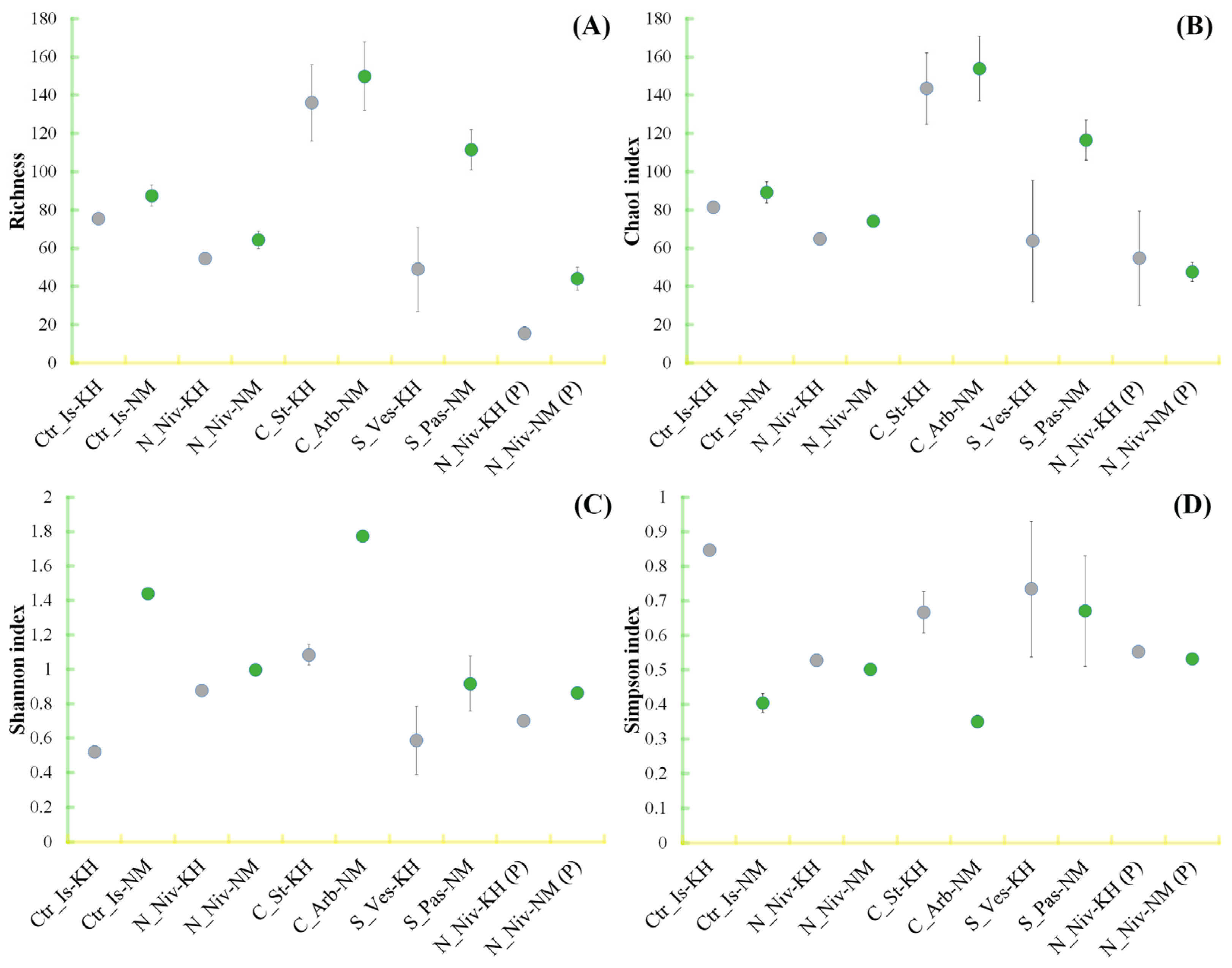

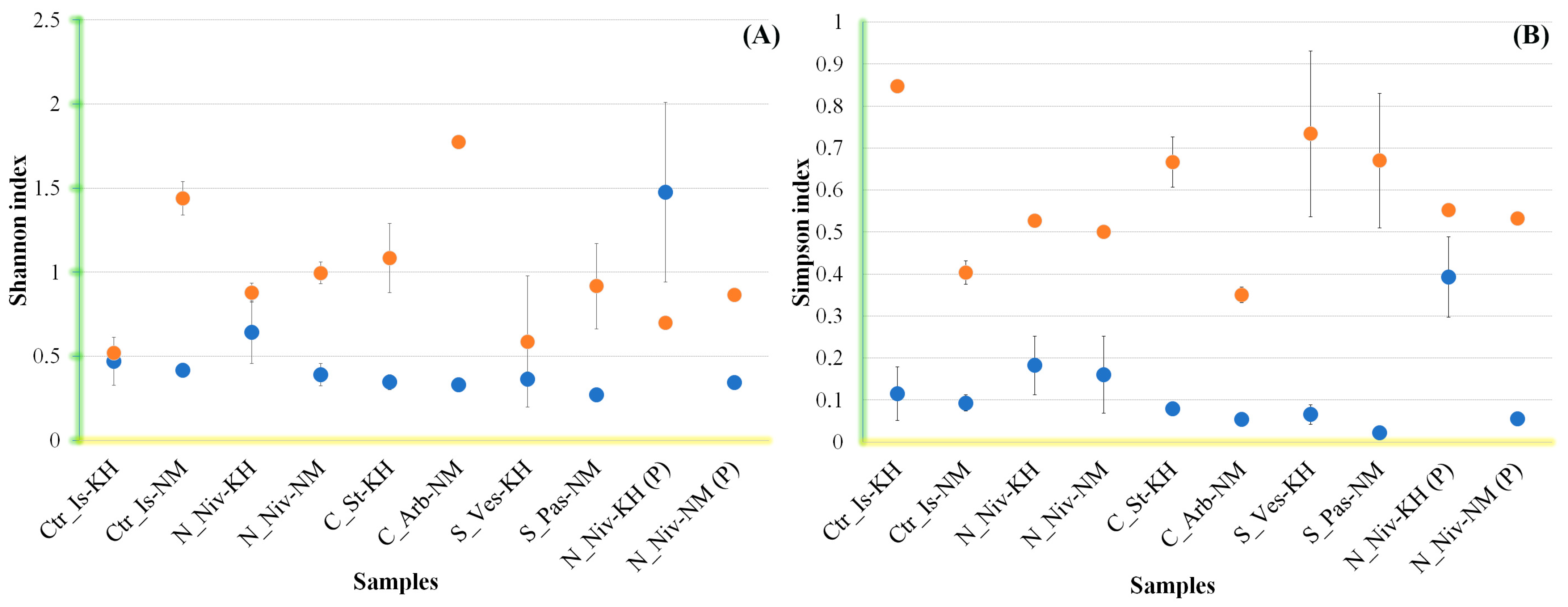

3.4. Alpha Diversity in Mycobiomes

3.5. Analysis of the Taxonomic Affiliation and Relative Contribution of the Dominant OTUs

3.6. The Relationship Between the Presence of Fungal Taxa and Lichen Species, and Their Geographical Location

3.7. Search for Epiphytic and Endophytic Fungal Groups in Nephromopsis nivalis

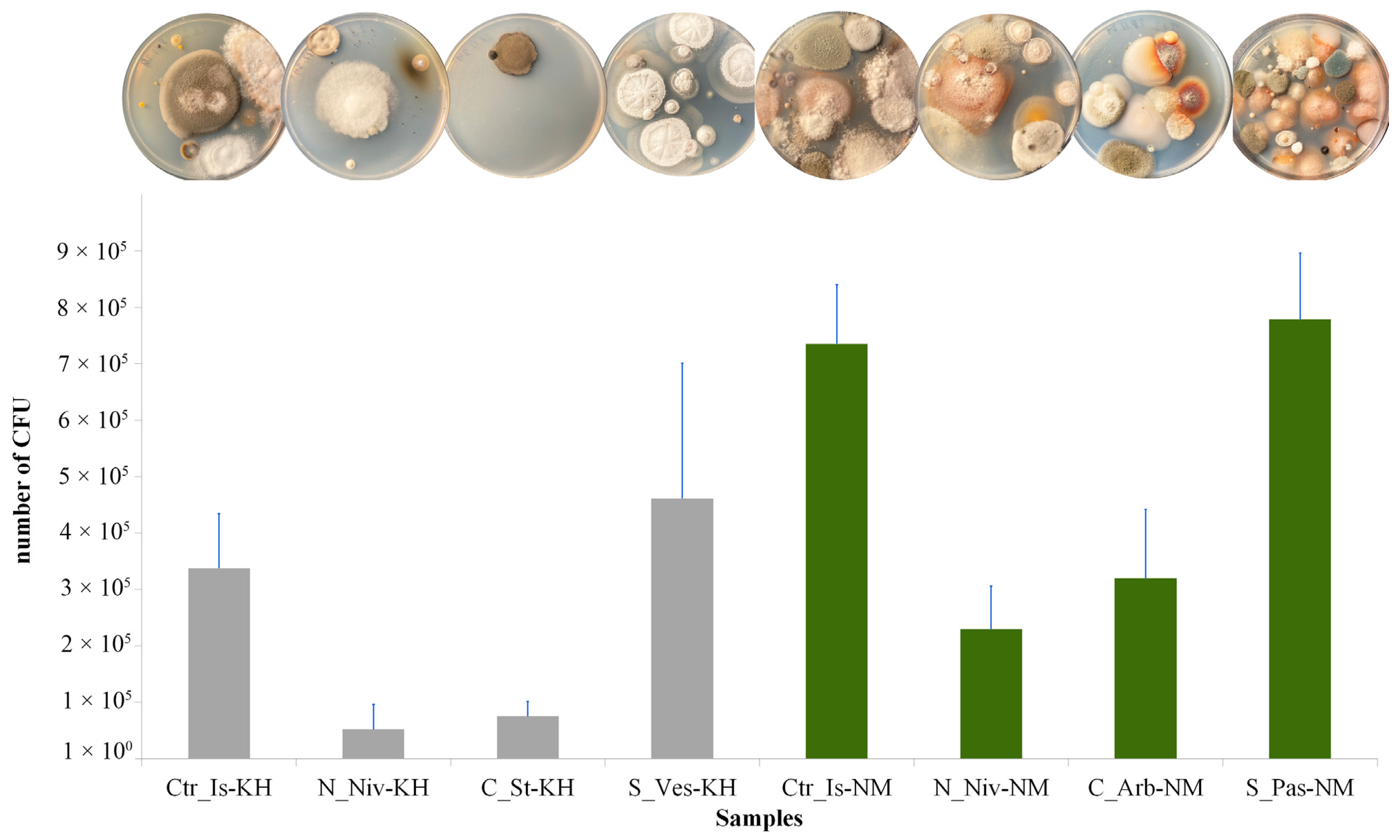

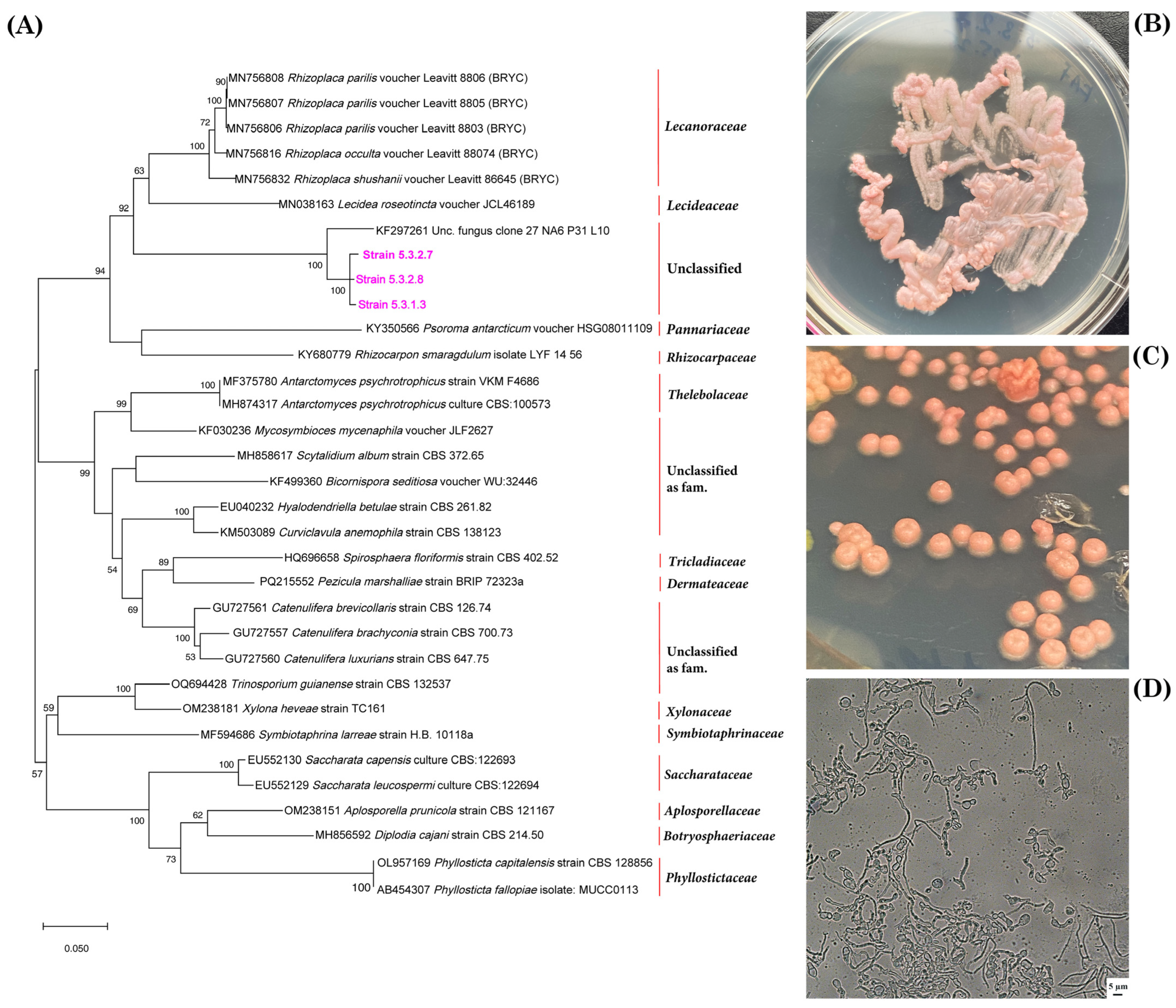

3.8. Analysis of the Diversity of Cultivated Fungi

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| OTU | Operational Taxonomic Unit |

| PBS | Phosphate-Saline Buffer |

| CTAB | Cetyltrimethylammonium Bromide |

| BLAST | Basic Local Alignment Search Tool |

| KPABG | Kola Polar Alpine Botanical Garden |

| PABGI KSC RAS | Polar-Alpine Botanical Garden-Institute of the Kola Science Center of the Russian Academy of Sciences |

| CFU | Colony-Forming Units |

References

- Grube, M.; Berg, G. Microbial Consortia of Bacteria and Fungi with Focus on the Lichen Symbiosis. Fungal Biol. Rev. 2009, 23, 72–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, S.T.; Berg-Lyons, D.; Lauber, C.L.; Walters, W.A.; Knight, R.; Fierer, N. A Preliminary Survey of Lichen Associated Eukaryotes Using Pyrosequencing. Lichenologist 2012, 44, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrey, J.D.; Diederich, P. Lichenicolous Fungi: Interactions, Evolution, and Biodiversity. Bryologist 2003, 106, 80–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moya, P.; Molins, A.; Martínez-Alberola, F.; Muggia, L.; Barreno, E. Unexpected Associated Microalgal Diversity in the Lichen Ramalina farinacea Is Uncovered by Pyrosequencing Analyses. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0175091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lücking, R.; Leavitt, S.D.; Hawksworth, D.L. Species in Lichen-Forming Fungi: Balancing between Conceptual and Practical Considerations, and between Phenotype and Phylogenomics. Fungal Divers. 2021, 109, 99–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suryanarayanan, T.S.; Thirunavukkarasu, N.; Hariharan, G.N.; Balaj, P. Occurrence of Non-Obligate Microfungi inside Lichen Thalli. Sydowia 2005, 57, 120–130. [Google Scholar]

- Hafellner, J. Focus on Lichenicolous Fungi: Diversity and Taxonomy under the Principle “One Fungus—One Name”. Biosyst. Ecol. Ser. 2018, 34, 227–243. [Google Scholar]

- Diederich, P.; Lawrey, J.D.; Ertz, D. The 2018 Classification and Checklist of Lichenicolous Fungi, with 2000 Non-Lichenized, Obligately Lichenicolous Taxa. Bryologist 2018, 121, 340–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhurbenko, M. Lichenicolous Fungi from the Holarctic. Part III: New Reports and a Key to Species on Hypogymnia. Opusc. Philolichenum 2020, 19, 180–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhurbenko, M.P.; Diederich, P.; Gagarina, L.V. Lichenicolous Fungi from Vietnam, with the Description of Four New Species. Herzogia 2021, 33, 525–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhurbenko, M. Lichenicolous Fungi from the Holarctic. Part IV: New Reports and a Key to Species on Dermatocarpon. Opusc. Philolichenum 2021, 20, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, A.E.; Miadlikowska, J.; Higgins, K.L.; Sarvate, S.D.; Gugger, P.; Way, A.; Hofstetter, V.; Kauff, F.; Lutzoni, F. A Phylogenetic Estimation of Trophic Transition Networks for Ascomycetous Fungi: Are Lichens Cradles of Symbiotrophic Fungal Diversification? Syst. Biol. 2009, 58, 283–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muggia, L.; Fleischhacker, A.; Kopun, T.; Grube, M. Extremotolerant Fungi from Alpine Rock Lichens and Their Phylogenetic Relationships. Fungal Divers. 2016, 76, 119–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muggia, L.; Pérez-Ortega, S.; Ertz, D. Muellerella, a Lichenicolous Fungal Genus Recovered as Polyphyletic within Chaetothyriomycetidae (Eurotiomycetes, Ascomycota). Plant Fungal Syst. 2019, 64, 367–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muggia, L.; Quan, Y.; Gueidan, C.; Al-Hatmi, A.M.S.; Grube, M.; de Hoog, S. Sequence Data from Isolated Lichen-Associated Melanized Fungi Enhance Delimitation of Two New Lineages within Chaetothyriomycetidae. Mycol. Prog. 2021, 20, 911–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poelt, J. Über parasitische Flechten. II. Planta 1958, 51, 288–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moya, P.; Molins, A.; Chiva, S.; Bastida, J.; Barreno, E. Symbiotic Microalgal Diversity within Lichenicolous Lichens and Crustose Hosts on Iberian Peninsula Gypsum Biocrusts. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 14060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kachalkin, A.V.; Glushakova, A.M.; Pankratov, T.A. Yeast Population of the Kindo Peninsula Lichens. Microbiology 2017, 86, 786–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kachalkin, A.; Tomashevskaya, M.; Pankratov, T.; Yurkov, A. Endothallic Yeasts in the Terricolous Lichens Cladonia. Mycol. Prog. 2024, 23, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suryanarayanan, T.S.; Thirunavukkarasu, N. Endolichenic Fungi: The Lesser Known Fungal Associates of Lichens. Mycology 2017, 8, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleischhacker, A.; Grube, M.; Kopun, T.; Hafellner, J.; Muggia, L. Community Analyses Uncover High Diversity of Lichenicolous Fungi in Alpine Habitats. Microb. Ecol. 2015, 70, 348–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muggia, L.; Kopun, T.; Grube, M. Effects of Growth Media on the Diversity of Culturable Fungi from Lichens. Molecules 2017, 22, 824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kachalkin, A.V.; Tomashevskaya, M.A.; Pankratov, T.A. Heterocephalacria septentrionalis sp. nov. Fungal Planet Description Sheets: 1042–1111. Persoonia-Mol. Phylogeny Evol. Fungi 2020, 44, 301–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kachalkin, A.V.; Tomashevskaya, M.A.; Pankratov, T.A. Teunia lichenophila, sp. nov. Fungal Planet Description Sheets: 1182–1283. Persoonia-Mol. Phylogeny Evol. Fungi 2021, 46, 313–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cometto, A.; Leavitt, S.D.; Millanes, A.M.; Wedin, M.; Grube, M.; Muggia, L. The Yeast Lichenosphere: High Diversity of Basidiomycetes from the Lichens Tephromela atra and Rhizoplaca melanophthalma. Fungal Biol. 2022, 126, 587–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diederich, P.; Millanes, A.M.; Wedin, M.; Lawrey, J.D. Flora of Lichenicolous Fungi, Volume 1: Basidiomycota; National Museum of Natural History: Luxembourg, 2022; ISBN 978-2-919877-26-3. [Google Scholar]

- Zhurbenko, M.P.; Brackel, W. von Checklist of Lichenicolous Fungi and Lichenicolous Lichens of Svalbard, Including New Species, New Records and Revisions. Herzogia 2013, 26, 323–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suija, A.; Zhurbenko, M.P.; Stepanchikova, I.S.S.; Himelbrant, D.E.; Kuznetsova, E.S.; Motiejūnaitė, J. Kukwaea pubescens gen. et sp. Nova (Helotiales, Incertae Sedis), a New Lichenicolous Fungus on Cetraria islandica, and a Key to the Lichenicolous Fungi Occurring on Cetraria S. Str. Phytotaxa 2020, 459, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardinale, M.; Steinová, J.; Rabensteiner, J.; Berg, G.; Grube, M. Age, Sun and Substrate: Triggers of Bacterial Communities in Lichens. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2012, 4, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klarenberg, I.J.; Keuschnig, C.; Warshan, D.; Jónsdóttir, I.S.; Vilhelmsson, O. The Total and Active Bacterial Community of the Chlorolichen Cetraria islandica and Its Response to Long-Term Warming in Sub-Arctic Tundra. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 540404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Wei, X.-L.; Zhang, Y.-Q.; Liu, H.-Y.; Yu, L.-Y. Diversity and Distribution of Lichen-Associated Fungi in the Ny-Ålesund Region (Svalbard, High Arctic) as Revealed by 454 Pyrosequencing. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 14850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shishido, T.K.; Wahlsten, M.; Laine, P.; Rikkinen, J.; Lundell, T.; Auvinen, P. Microbial Communities of Cladonia Lichens and Their Biosynthetic Gene Clusters Potentially Encoding Natural Products. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pino-Bodas, R.; Zhurbenko, M.P.; Stenroos, S. Phylogenetic Placement within Lecanoromycetes of Lichenicolous Fungi Associated with Cladonia and Some Other Genera. Persoonia 2017, 39, 91–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhurbenko, M.; Zhurbenko, M. Lichenicolous Fungi and Lichens Growing on Stereocaulon from the Holarctic, with a Key to the Known Species. Opusc. Philolichenum 2010, 8, 9–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhurbenko, M.; Zhurbenko, M.; Kukwa, M.; Oset, M. Roselliniella stereocaulorum (Sordariales, Ascomycota), a New Lichenicolous Fungus from the Holarctic. Mycotaxon 2009, 109, 323–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vančurová, L.; Muggia, L.; Peksa, O.; Řídká, T.; Škaloud, P. The Complexity of Symbiotic Interactions Influences the Ecological Amplitude of the Host: A Case Study in Stereocaulon (Lichenized Ascomycota). Mol. Ecol. 2018, 27, 3016–3033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Woo, J.-J.; Sesal, C.; Gökalsın, B.; Eldem, V.; Açıkgöz, B.; Başaran, T.I.; Kurtuluş, G.; Hur, J.-S. Continental Scale Comparison of Mycobiomes in Parmelia and Peltigera Lichens from Turkey and South Korea. BMC Microbiol. 2024, 24, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, A.; Hilton, B. The Lichens of Great Britain and Ireland. Edited by C. W. Smith, A. Aptroot, B.J. Coppins, A. Fletcher, O.L. Gilbert, P.W. James and P. A. Wolseley. London: The British Lichen Society, Department of Botany, The Natural History Museum, Cromwell Road, London SW7 5BD. Pp. x + 1046. ISBN 978 09540418 8 5 Hardback. Price £45 (plus £7 p & p) to BLS members; £65 (plus £7 p & p) to non-members. Orders and cheques to Richmond Publishing Co Ltd., P.O. Box 963, Slough, SL2 3RS. Lichenologist 2010, 42, 123–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westberg, M.; Moberg, R.; Myrdal, M.; Nordin, A.; Ekman, S. Santesson’s Checklist of Fennoscandian Lichen-Forming and Lichenicolous Fungi; Uppsala University Museum of Evolution: Uppsala, Sweden, 2021; p. 856. ISBN 978-91-519-9881-7. Available online: https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1577869/FULLTEXT01.pdf (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- O’Donnell, K.L. Fusarium and its near relatives. In The Fungal Holomorph: Mitotic, Meiotic and Pleomorphic Speciation in Fungal Systematics; Reynolds, D.R., Taylor, J.W., Eds.; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 1993; pp. 225–233. [Google Scholar]

- Nikitin, D.A.; Ivanova, E.A.; Zhelezova, A.D.; Semenov, M.V.; Gadzhiumarov, R.G.; Tkhakakhova, A.K.; Chernov, T.I.; Ksenofontova, N.A.; Kutovaya, O.V. Assessment of the Impact of No-Till and Conventional Tillage Technologies on the Microbiome of Southern Agrochernozems. Eurasian Soil Sci. 2020, 53, 1782–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Li, M.; Knyaz, C.; Tamura, K. MEGA X: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis across Computing Platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018, 35, 1547–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okonechnikov, K.; Golosova, O.; Fursov, M.; the UGENE team. Unipro UGENE: A Unified Bioinformatics Toolkit. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 1166–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BLAST: Basic Local Alignment Search Tool. Available online: https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi (accessed on 18 October 2025).

- Vu, D.; Groenewald, M.; de Vries, M.; Gehrmann, T.; Stielow, B.; Eberhardt, U.; Al-Hatmi, A.; Groenewald, J.Z.; Cardinali, G.; Houbraken, J.; et al. Large-Scale Generation and Analysis of Filamentous Fungal DNA Barcodes Boosts Coverage for Kingdom Fungi and Reveals Thresholds for Fungal Species and Higher Taxon Delimitation. Stud. Mycol. 2019, 92, 135–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellemain, E.; Carlsen, T.; Brochmann, C.; Coissac, E.; Taberlet, P.; Kauserud, H. ITS as an Environmental DNA Barcode for Fungi: An in Silico Approach Reveals Potential PCR Biases. BMC Microbiol. 2010, 10, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickman, M. Some Indices of Diversity. Ecology 1968, 49, 1191–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, E.H. Measurement of Diversity. Nature 1949, 163, 688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.D.M.; Richards, T.A.; Hawksworth, D.L.; Bass, D. Validation and Justification of the Phylum Name Cryptomycota Phyl. Nov. IMA Fungus 2011, 2, 173–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedersoo, L.; Bahram, M.; Puusepp, R.; Nilsson, R.H.; James, T.Y. Novel Soil-Inhabiting Clades Fill Gaps in the Fungal Tree of Life. Microbiome 2017, 5, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Mendoza, F.; Fleischhacker, A.; Kopun, T.; Grube, M.; Muggia, L. ITS1 Metabarcoding Highlights Low Specificity of Lichen Mycobiomes at a Local Scale. Mol. Ecol. 2017, 26, 4811–4830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhurbenko, M.P. Lichenicolous Fungi Growing on Thamnolia, Mainly from the Holarctic, with a Worldwide Key to the Known Species. Lichenologist 2012, 44, 147–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esslinger, T.L.; Esslinger, T.L. A Cumulative Checklist for the Lichen-Forming, Lichenicolous and Allied Fungi of the Continental United States and Canada, Version 21. Opusc. Philolichenum 2016, 15, 136–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Song, W.; Yu, D.; Kishan Sudini, H.; Kang, Y.; Lei, Y.; Huai, D.; Wang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Wang, X.; et al. Genetic, Phenotypic, and Pathogenic Variation Among Athelia rolfsii, the Causal Agent of Peanut Stem Rot in China. Plant Dis. 2022, 106, 2722–2729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, J.P.M.; Hughes, D.P. Chapter One—Diversity of Entomopathogenic Fungi: Which Groups Conquered the Insect Body? In Advances in Genetics; Lovett, B., St. Leger, R.J., Eds.; Genetics and Molecular Biology of Entomopathogenic Fungi; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016; Volume 94, pp. 1–39. [Google Scholar]

- Gazis, R.; Skaltsas, D.; Chaverri, P. Novel Endophytic Lineages of Tolypocladium Provide New Insights into the Ecology and Evolution of Cordyceps-like Fungi. Mycologia 2014, 106, 1090–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.-H.; Yuan, F.-X.; Groenewald, M.; Bensch, K.; Yurkov, A.M.; Li, K.; Han, P.-J.; Guo, L.-D.; Aime, M.C.; Sampaio, J.P.; et al. Diversity and Phylogeny of Basidiomycetous Yeasts from Plant Leaves and Soil: Proposal of Two New Orders, Three New Families, Eight New Genera and One Hundred and Seven New Species. Stud. Mycol. 2020, 96, 17–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basavand, E.; Babaeizad, V.; Mirhosseini, H.A.; Dehghan Niri, M. Occurrence of Leaf Spot Disease Caused by Phoma herbarum on Oregano in Iran. J. Plant Pathol. 2020, 102, 575–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.C.; Henriques, J.; Diogo, E.; Ramos, A.P.; Bragança, H. First Report of Sydowia polyspora Causing Disease on Pinus pinea Shoots. For. Pathol. 2020, 50, e12570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imoulan, A.; Hussain, M.; Kirk, P.M.; El Meziane, A.; Yao, Y.-J. Entomopathogenic Fungus Beauveria: Host Specificity, Ecology and Significance of Morpho-Molecular Characterization in Accurate Taxonomic Classification. J. Asia Pac. Entomol. 2017, 20, 1204–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Z.; Tian, L.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, X.; Lei, Y.; Tang, F. Mycobiome Mediates the Interaction between Environmental Factors and Mycotoxin Contamination in Wheat Grains. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 928, 172494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierra, M.A.; Danko, D.C.; Sandoval, T.A.; Pishchany, G.; Moncada, B.; Kolter, R.; Mason, C.E.; Zambrano, M.M. The Microbiomes of Seven Lichen Genera Reveal Host Specificity, a Reduced Core Community and Potential as Source of Antimicrobials. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jóźwiak, M.A. Ectohydricity of Lichens and Role of Cortex Layer in Accumulation of Heavy Metals. Ecol. Chem. Eng. 2014, 20, 659–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masumoto, H.; Degawa, Y. The Effect of Surface Sterilization and the Type of Sterilizer on the Genus Composition of Lichen-Inhabiting Fungi with Notes on Some Frequently Isolated Genera. Mycoscience 2019, 60, 331–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.-Y.; Yang, J.H.; Woo, J.-J.; Oh, S.-O.; Hur, J.-S. Diversity and Distribution Patterns of Endolichenic Fungi in Jeju Island, South Korea. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maduranga, K.; Attanayake, R.N.; Santhirasegaram, S.; Weerakoon, G.; Paranagama, P.A. Molecular Phylogeny and Bioprospecting of Endolichenic Fungi (ELF) Inhabiting in the Lichens Collected from a Mangrove Ecosystem in Sri Lanka. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0200711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.H.; Kim, K.M.; Elvebakk, A.; Kim, O.-S.; Jeong, G.; Hong, S.G. Algal and Fungal Diversity in Antarctic Lichens. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 2015, 62, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, H.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, S.; Bose, T.; Chang, R. Fungal Diversity Associated with Thirty-Eight Lichen Species Revealed a New Genus of Endolichenic Fungi, Intumescentia Gen. Nov. (Teratosphaeriaceae). J. Fungi 2023, 9, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gueidan, C.; Hill, D.J.; Miadlikowska, J.; Lutzoni, F. 4 Pezizomycotina: Lecanoromycetes. In Systematics and Evolution: Part B; McLaughlin, D.J., Spatafora, J.W., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2015; pp. 89–120. ISBN 978-3-662-46011-5. [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto, K.; Sugawa, G.; Takeda, K.; Degawa, Y. Tolypocladium bacillisporum (Ophiocordycipitaceae): A New Parasite of Elaphomyces from Japan. Truffology 2022, 5, 15–21. [Google Scholar]

- Vilhelmsson, O.; Sigurbjörnsdóttir, A.; Grube, M.; Höfte, M. Are Lichens Potential Natural Reservoirs for Plant Pathogens? Mol. Plant Pathol. 2016, 17, 143–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crous, P.W.; Rossman, A.Y.; Aime, M.C.; Allen, W.C.; Burgess, T.; Groenewald, J.Z.; Castlebury, L.A. Names of Phytopathogenic Fungi: A Practical Guide. Phytopathology 2021, 111, 1500–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mawarda, P.C.; van der Kaaij, R.; Dini-Andreote, F.; Duijker, D.; Stech, M.; Speksnijder, A.G. Unveiling the Ecological Processes Driving Soil and Lichen Microbiome Assembly along an Urbanization Gradient. npj Biofilms Microbiomes 2025, 11, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sampling Places | Coordinates | Sample ID | Species |

|---|---|---|---|

| Massif Khibiny. Botanical Cirque. Slope of scree. Tundra belt. Boulder. Rock. ±0 cm below snow level | 67°38′46″ N 33°38′55″ E | Ctr_Is-KH | Cetraria islandica (L.) Ach. |

| 67°38′47″ N 33°38′55″ E | N_Niv-KH | Nephromopsis nivalis (L.) Divakar, A.Crespo & Lumbsch (syn. Flavocetraria nivalis (L.) Kärnefelt & A.Thell) | |

| Massif Khibiny. Botanical Cirque. Moraine slope. Border of birch forest. Soil. 20 cm below snow level | C_St-KH | Cladonia stellaris (Opiz) Pouzar & Vĕzda | |

| Massif Khibiny. Slope of Botanical Cirque. Tundra belt. Rock vertical wall in ice film. Above snow level ~100 cm | 67°38′31″ N 33°39′19″ E | S_Ves-KH | Stereocaulon vesuvianum Pers. |

| Nenets Autonomous Okrug, Iskateley settlement, Layavozhskaya road | 67°39′22″ N 53°8′25″ E | Ctr_Is-NM | Cetraria islandica (L.) Ach. |

| N_Niv-NM | Nephromopsis nivalis (L.) Divakar, A.Crespo & Lumbsch | ||

| C_Arb-NM | Cladonia arbuscula (Wallr.) Flot. | ||

| S_Pas-NM | Stereocaulon paschale (L.) Hoffm. |

| Taxonomic Level of Identification | Percentage of Similarity |

|---|---|

| Species definitively identified | >98% |

| New species within a genus | 94.3–98% |

| New genus within a family | 88.5–94.2% |

| New family within an order | 81.2–88.4% |

| New order within a class | 80.9–81.1% |

| New class within a phylum | <80.9% |

| Sample ID | Otu Number | GenBank No. of Sequence | Otu Abundance (med.), % * | Query Cover, % | Identity, % | Genbank No. of a Nearest Sequence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ctr_Is_KH Ctr_Is_NM | Otu3 | PX502201 | 92 27 | 94 | 100 | MG250320 |

| Ctr_Is_KH Ctr_Is_NM | Otu17 | PX502207 | 1.5 57 | 92 | 99.57 | KY764999 |

| N_Niv_KH N_Niv_NM | Otu232 | PX502209 | 66.5 65 | 100 | 99.6 | GU067707 |

| N_Niv_KH N_Niv_NM | Otu1 | PX502199 | 30 30 | 94 | 100 | MG461626 |

| C_St_KH | Otu2 | PX502200 | 81.5 | 77 | 100 | MK812280 |

| C_Arb_NM | Otu6 | PX502203 | 27.6 | 98 | 99.59 | OL694693 |

| Otu7 | PX502204 | 27.5 | 91 | 99.56 | MK508932 | |

| Otu9 | PX502205 | 23.8 | 98 | 99.59 | KY119382 | |

| S_Ves_KH | Otu4 | PX502202 | 82.5 | 91 | 98.25 | LC742699 |

| S_Pas_NM | Otu25 | PX502208 | 57 | 94 | 100 | HQ650690 |

| Otu12 | PX502206 | 33 | 95 | 100 | MT925689 |

| Sample ID | Reads Initial | Reads in OTU | Richness | Mapped Percent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ctr_Is_KH | 15,353 ± 1394 | 13,938 ± 986 | 123 ± 0 | 90.95 ± 1.84 |

| N_Niv_KH | 28,561 ± 3294 | 27,264 ± 3091 | 120 ± 11 | 95.48 ± 0.19 |

| N_Niv_KH (processed) * | 28,698 ± 2102 | 27,614 ± 2086 | 40 ± 2.5 | 96.21 ± 0.22 |

| C_St_KH | 27,784 ± 3024 | 26,155 ± 2674 | 256 ± 24 | 94.21 ± 0.62 |

| S_Ves_KH | 15,340 ± 758 | 13,348 ± 746 | 77 ± 26 | 87.00 ± 0.56 |

| Ctr_Is_NM | 8766 ± 2936 | 7775 ± 2596 | 102 ± 9 | 88.72 ± 0.10 |

| N_Niv_NM | 28,933 ± 1806 | 27,368 ± 1820 | 139 ± 22 | 94.56 ± 0.38 |

| N_Niv_NM (processed) * | 19,160 ± 415 | 18,316 ± 406 | 80 ± 18 | 95.60 ± 0.05 |

| C_Arb_NM | 10,290 ± 1709 | 9053 ± 1540 | 186 ± 23 | 87.92 ± 0.36 |

| S_Pas_NM | 19,976 ± 216 | 13,770 ± 1020 | 172 ± 1 | 69.00 ± 5.86 |

| Sample ID | OTU, % Mycobiont | OTU, % Others |

|---|---|---|

| Ctr_Is_KH | 93.44 ± 0.86 | 6.56 ± 0.86 |

| N_Niv_KH | 95.84 ± 1.44 | 4.16 ± 1.44 |

| N_Niv_KH (processed) * | 98.98 ± 0.31 | 1.02 ± 0.31 |

| C_St_KH | 81.17 ± 3.6 | 18.83 ± 3.60 |

| S_Ves_KH | 96.18 ± 2.84 | 3.82 ± 2.84 |

| Ctr_Is_NM | 83.91 ± 1.06 | 16.09 ± 1.06 |

| N_Niv_NM | 94.68 ± 1.17 | 5.32 ± 1.17 |

| N_Niv_NM (processed) * | 96.35 ± 0.15 | 2.76 ± 0.68 |

| C_Arb_NM | 80.70 ± 0.12 | 19.31 ± 0.12 |

| S_Pas_NM | 91.96 ± 0.98 | 8.04 ± 0.98 |

| Sample ID | Richness | Shannon Index | Simpson Index |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ctr_Is_KH | 10 | 2.24 | 0.13 |

| Ctr_Is_NM | 15 | 2.82 | 0.29 |

| N_Niv_KH | 5 | 1.73 | 0.17 |

| N_Niv_NM | 2 | 0.87 | 0.50 |

| S_Ves_KH | 4 | 1.06 | 0.54 |

| S_Pas_NM | 5 | 1.67 | 0.21 |

| C_Arb_NM | 9 | 2.30 | 0.15 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hakobjanyan, A.; Melekhin, A.; Sukhacheva, M.; Beletsky, A.; Pankratov, T. Mycobiomes of Six Lichen Species from the Russian Subarctic: A Culture-Independent Analysis and Cultivation Study. J. Fungi 2025, 11, 848. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof11120848

Hakobjanyan A, Melekhin A, Sukhacheva M, Beletsky A, Pankratov T. Mycobiomes of Six Lichen Species from the Russian Subarctic: A Culture-Independent Analysis and Cultivation Study. Journal of Fungi. 2025; 11(12):848. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof11120848

Chicago/Turabian StyleHakobjanyan, Armen, Alexey Melekhin, Marina Sukhacheva, Alexey Beletsky, and Timofey Pankratov. 2025. "Mycobiomes of Six Lichen Species from the Russian Subarctic: A Culture-Independent Analysis and Cultivation Study" Journal of Fungi 11, no. 12: 848. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof11120848

APA StyleHakobjanyan, A., Melekhin, A., Sukhacheva, M., Beletsky, A., & Pankratov, T. (2025). Mycobiomes of Six Lichen Species from the Russian Subarctic: A Culture-Independent Analysis and Cultivation Study. Journal of Fungi, 11(12), 848. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof11120848