Association Between Smoking Hookahs (Shishas) and Higher Risk of Obesity: A Systematic Review of Population-Based Studies

Abstract

1. Introduction

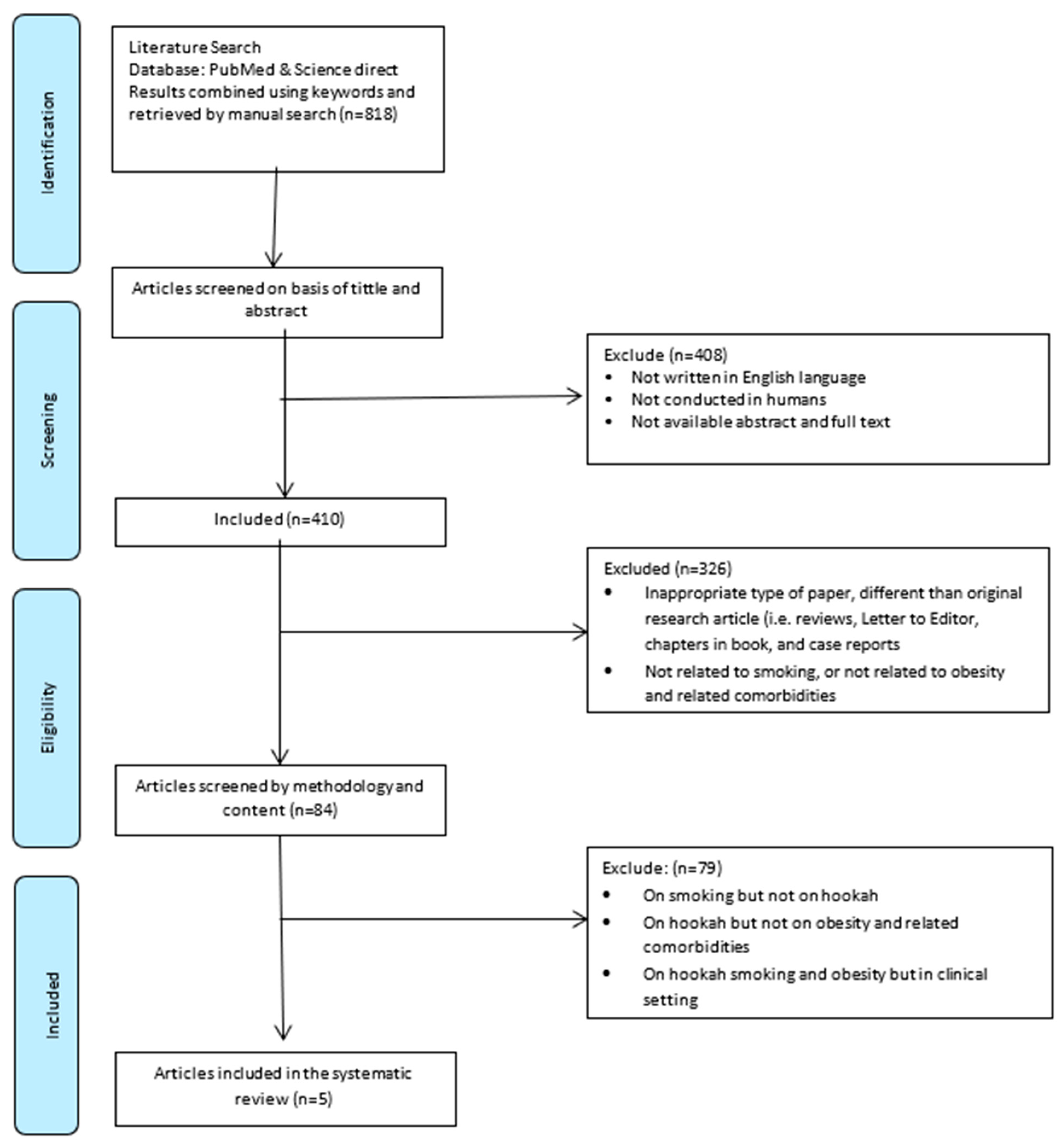

2. Methods

2.1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.2. Information Source and Search Strategy

2.3. Study Selection

2.4. Data Collection Process and Data Items

2.5. Data Synthesis

3. Results

3.1. Narrative Synthesis

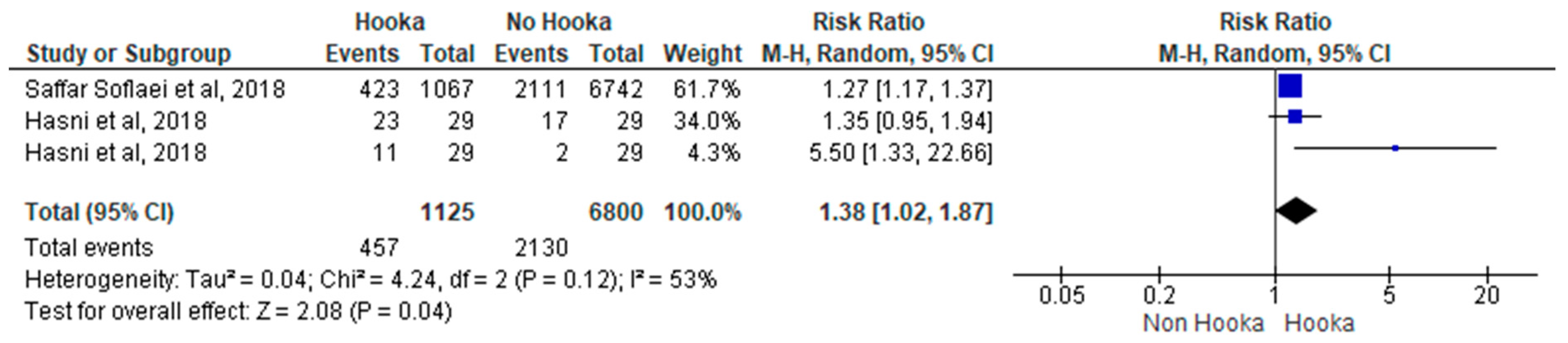

3.2. Meta-Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Clinical Implications

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ray, C. The hookah—The Indian waterpipe. Curr. Sci. 2009, 96, 1319–1323. [Google Scholar]

- Brockman, L.N.; Pumper, M.A.; Christakis, D.A.; Moreno, M.A. Hookah’s new popularity among US college students: A pilot study of the characteristics of hookah smokers and their Facebook displays. BMJ Open 2012, 2, e001709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maziak, W.; Taleb, Z.B.; Bahelah, R.; Islam, F.; Jaber, R.; Auf, R.; Salloum, R.G. The global epidemiology of waterpipe smoking. Tob. Control 2015, 24, i3–i12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soule, E.K.; Lipato, T.; Eissenberg, T. Waterpipe tobacco smoking: A new smoking epidemic among the young? Curr. Pulmonol. Rep. 2015, 4, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szyfter, A.; Giefing, M. Is waterpipe smoking a safe alterative for cigarette smoking? Przegl. Lek. 2012, 69, 1090–1094. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Awan, K.H.; Siddiqi, K.; Patil, S.; Hussain, Q.A. Assessing the Effect of Waterpipe Smoking on Cancer Outcome—A Systematic Review of Current Evidence. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2017, 18, 495–502. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, H.T.; Koriyama, C.; Tokudome, S.; Tran, H.H.; Tran, L.T.; Nandakumar, A.; Akiba, S.; Le, N.T. Waterpipe Tobacco Smoking and Gastric Cancer Risk among Vietnamese Men. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0165587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montazeri, Z.; Nyiraneza, C.; El-Katerji, H.; Little, J. Waterpipe smoking and cancer: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Tob. Control 2017, 26, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warnakulasuriya, S. Waterpipe smoking, oral cancer and other oral health effects. Evid. Based Dent. 2011, 12, 44–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meo, S.A.; AlShehri, K.A.; AlHarbi, B.B.; Barayyan, O.R.; Bawazir, A.S.; Alanazi, O.A.; Al-Zuhair, A.R. Effect of shisha (waterpipe) smoking on lung functions and fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) among Saudi young adult shisha smokers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2014, 11, 9638–9648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahtouee, M.; Maleki, N.; Nekouee, F. The prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in hookah smokers. Chron. Respir. Dis. 2018, 15, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- She, J.; Yang, P.; Wang, Y.; Qin, X.; Fan, J.; Wang, Y.; Gao, G.; Luo, G.; Ma, K.; Li, B.; et al. Chinese water-pipe smoking and the risk of COPD. Chest 2014, 146, 924–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aslam, H.M.; Saleem, S.; German, S.; Qureshi, W.A. Harmful effects of shisha: Literature review. Int. Arch. Med. 2014, 7, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, M.D.; Rezk-Hanna, M.; Rader, F.; Mason, O.R.; Tang, X.; Shidban, S.; Rosenberry, R.; Benowitz, N.L.; Tashkin, D.P.; Elashoff, R.M.; et al. Acute Effect of Hookah Smoking on the Human Coronary Microcirculation. Am. J. Cardiol. 2016, 117, 1747–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatnagar, A.; Maziak, W.; Eissenberg, T.; Ward, K.D.; Thurston, G.; King, B.A.; Sutfin, E.L.; Cobb, C.O.; Griffiths, M.; Goldstein, L.B.; et al. Water Pipe (Hookah) Smoking and Cardiovascular Disease Risk: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2019, 139, e917–e936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Ghoch, M.; Fakhoury, R. Challenges and New Directions in Obesity Management: Lifestyle modification programs, pharmacotherapy and Bariatric surgery. J. Popul. Ther. Clin. Pharmacol. 2019, 26, e1–e4. [Google Scholar]

- Kreidieh, D.; Itani, L.; El Masri, D.; Tannir, H.; Citarella, R.; El Ghoch, M. Association between Sarcopenic Obesity, Type 2 Diabetes, and Hypertension in Overweight and Obese Treatment-Seeking Adult Women. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2018, 5, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khazem, S.; Itani, L.; Kreidieh, D.; El Masri, D.; Tannir, H.; Citarella, R.; El Ghoch, M. Reduced Lean Body Mass and Cardiometabolic Diseases in Adult Males with Overweight and Obesity: A Pilot Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreidieh, D.; Itani, L.; El Kassas, G.; El Masri, D.; Calugi, S.; Grave, R.D.; El Ghoch, M. Long-term Lifestyle-modification Programs for Overweight and Obesity Management in the Arab States: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Curr. Diabetes Rev. 2018, 14, 550–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itani, L.; Calugi, S.; Dalle Grave, R.; Kreidieh, D.; El Kassas, G.; El Masri, D.; Tannir, H.; Harfoush, A.; El Ghoch, M. The Association between Body Mass Index and Health-Related Quality of Life in Treatment-Seeking Arab Adults with Obesity. Med. Sci. 2018, 6, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, J.L.; Jones, J.; Bolleddu, S.I.; Vanthenapalli, S.; Rodgers, L.E.; Shah, K.; Karia, K.; Panguluri, S.K. Cardiovascular Risks Associated with Gender and Aging. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2019, 6, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lowe, Y. Smoking Shisha Linked to Diabetes and Obesity, Study Finds; The Telegraph: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, W.S.; Wilson, M.C.; Nishikawa, J.; Hayward, R.S. The well-built clinical question: A key to evidence-based decisions. ACP J. Club 1995, 123, A12–A13. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sawyer, S.M.; Azzopardi, P.S.; Wickremarathne, D.; Patton, G.C. The age of adolescence. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2018, 2, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gotzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. Ann. Int. Med. 2009, 151, W65–W94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gotzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. PLOS Med. 2009, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, S. The importance of PROSPERO to the National Institute for Health Research. Syst Rev. 2012, 1, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoy, D.; Brooks, P.; Woolf, A.; Blyth, F.; March, L.; Bain, C.; Baker, P.; Smith, E.; Buchbinder, R. Assessing risk of bias in prevalence studies: Modification of an existing tool and evidence of interrater agreement. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2012, 65, 934–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popay, J.; Roberts, H.; Sowden, A.; Petticrew, M.; Britten, N.; Arai, L.; Rodgers, M.; Britten, N.; Roen, K.; Duffy, S. Developing guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2005, 59, A7. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, M.; Katikireddi, S.V.; Sowden, A.; Thomson, H. Lack of transparency in reporting narrative synthesis of quantitative data: A methodological assessment of systematic reviews. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2019, 105, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Review Manager (RevMan); Version 5.3; The Nordic Cochrane Centre: Copenhagen, Denmark; The Cochrane: London, UK, 2014.

- Shafique, K.; Mirza, S.S.; Mughal, M.K.; Arain, Z.I.; Khan, N.A.; Tareen, M.F.; Ahmad, I. Water-pipe smoking and metabolic syndrome: A population-based study. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e39734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misra, A.; Vikram, N.K.; Gupta, R.; Pandey, R.M.; Wasir, J.S.; Gupta, V.P. Waist circumference cutoff points and action levels for Asian Indians for identification of abdominal obesity. Int. J. Obes. 2006, 30, 106–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ward, K.D.; Ahn, S.; Mzayek, F.; Al Ali, R.; Rastam, S.; Asfar, T.; Fouad, F.; Maziak, W. The relationship between waterpipe smoking and body weight: Population-based findings from Syria. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2015, 17, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Saffar Soflaei, S.; Darroudi, S.; Tayefi, M.; Nosrati Tirkani, A.; Moohebati, M.; Ebrahimi, M.; Esmaily, H.; Parizadeh, S.M.R.; Heidari-Bakavoli, A.R.; Ferns, G.A.; et al. Hookah smoking is strongly associated with diabetes mellitus, metabolic syndrome and obesity: A population-based study. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2018, 10, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alomari, M.A.; Al-Sheyab, N.A.; Ward, K.D. Adolescent Waterpipe Use is Associated with Greater Body Weight: The Irbid-TRY. Subst. Use Misuse 2018, 53, 1194–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasni, Y.; Bachrouch, S.; Mahjoub, M.; Maaroufi, A.; Rouatbi, S.; Ben Saad, H. Biochemical Data and Metabolic Profiles of Male Exclusive Narghile Smokers (ENSs) Compared with Apparently Healthy Nonsmokers (AHNSs). Am. J. Men’s Health 2019, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberti, K.G.; Zimmet, P.; Shaw, J. Metabolic syndrome—A new world-wide definition. A Consensus Statement from the International Diabetes Federation. Diabet. Med. 2006, 23, 469–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selim, G.M.; Fouad, H.; Ezzat, S. Impact of shisha smoking on the extent of coronary artery disease in patients referred for coronary angiography. Anadolu Kardiyol Derg 2013, 13, 647–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, R.; Starkey, F.; Holliday, J.; Audrey, S.; Bloor, M.; Parry-Langdon, N.; Hughes, R.; Moore, L. An informal school-based peer-led intervention for smoking prevention in adolescence (ASSIST): A cluster randomised trial. Lancet 2008, 371, 1595–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.; Michie, S.; Geraghty, A.W.; Yardley, L.; Gardner, B.; Shahab, L.; Stapleton, J.A.; West, R. Internet-based intervention for smoking cessation (StopAdvisor) in people with low and high socioeconomic status: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet Respir. Med. 2014, 2, 997–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koul, P.A.; Hajni, M.R.; Sheikh, M.A.; Khan, U.H.; Shah, A.; Khan, Y.; Ahangar, A.G.; Tasleem, R.A. Hookah smoking and lung cancer in the Kashmir valley of the Indian subcontinent. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2011, 12, 519–524. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kadhum, M.; Jaffery, A.; Haq, A.; Bacon, J.; Madden, B. Measuring the acute cardiovascular effects of shisha smoking: A cross-sectional study. JRSM Open 2014, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasat, V.; Ladda, R. Smoking and dental implants. J. Int. Soc. Prev. Commun. Dent. 2012, 2, 38–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Zaatari, Z.M.; Chami, H.A.; Zaatari, G.S. Health effects associated with waterpipe smoking. Tob. Control 2015, 24, i31–i43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, J.N.; Wang, B.; Jackson, K.J.; Donaldson, E.A.; Ryant, C.A. Characteristics of Hookah Tobacco Smoking Sessions and Correlates of Use Frequency Among US Adults: Findings from Wave 1 of the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Study. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2018, 20, 731–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Momenabadi, V.; Hossein Kaveh Ph, D.M.; Hashemi, S.Y.; Borhaninejad, V.R. Factors Affecting Hookah Smoking Trend in the Society: A Review Article. Addict. Health 2016, 8, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Abdollahifard, G.; Vakili, V.; Danaei, M.; Askarian, M.; Romito, L.; Palenik, C.J. Are the Predictors of Hookah Smoking Differ from Those of Cigarette Smoking? Report of a population-based study in Shiraz, Iran, 2010. Int. J. Prev. Med. 2013, 4, 459–466. [Google Scholar]

- Solem, R.C. Limitation of a cross-sectional study. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2015, 148, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruana, E.J.; Roman, M.; Hernandez-Sanchez, J.; Solli, P. Longitudinal studies. J. Thorac. Dis. 2015, 7, E537–E540. [Google Scholar]

| Study | Design | Country | Sample | Age | Primary Outcome | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shafique et al. 2012 | Population-based study | Pakistan | Total = 2032 HS = 325 of both genders | 30–75 years | • Association between HS and metabolic syndrome and components | • Metabolic syndrome was significantly higher among HS (33.1%) compared to NS. • HS were 3 times more likely to have metabolic syndrome compared with NS. • HS have significantly more hypertriglyceridemia, hyperglycaemia, hypertension, and abdominal obesity with respect to non-HS. |

| Ward et al. 2015 | Population-based study | Syria | Total = 2536, NS = 2134, former HS = 116, 251 non-daily HS = 251, daily HS = 35 of both genders | ≥18 years | • Associations of HS use status with BMI and obesity status | • Daily HS have nearly 2 BMI units greater than NS and had nearly three times the risk of having obesity. |

| Saffar Soflaei et al. 2018 | Population-based study | Iran | Total = 9840, NS = 6742, Ex-smoker = 976 CS = 864, HS = 1067, MS = 41 of both genders | 35–65 years | Association between HS and obesity, cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, metabolic syndrome, and dyslipidemia | • A positive association between HS and metabolic syndrome, diabetes, obesity, and dyslipidemia was not established in CS. |

| Alomari et al. 2018 | Population-based study | Jordan | Total = 2313 of both genders | In grades 7–10 | • Associations of obesity with HS | • HS when compared to nonusers and who smoked hookah weekly had twofold greater odds of having obesity than nonsmokers. |

| Hasni et al. 2018 | Population-based study | Tunisia | Total = 58, HS = 29, NS = 29 only males | 25–45 years | • Comparison in the biochemical data and the metabolic profile between HS and nonsmokers | • The mean BMI in HS was significantly higher when compared with that of nonsmokers and had a higher prevalence of obesity and abdominal obesity. |

| Shafique 2012 | Ward 2015 | Saffar Soflaei 2018 | Alomari 2018 | Hasni 2018 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Was the study’s target population a close representation of the national population in relation to relevant variables, e.g., age, sex, occupation? | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Was the sampling frame a true or close representation of the target population? | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Was some form of random selection used to select the sample, OR was a census undertaken? | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Was the likelihood of nonresponse bias minimal? | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Were data collected directly from the subjects as opposed to a proxy? | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Was an acceptable case definition used in the study? | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Was the study instrument that measured the parameter of interest shown to have reliability and validity (if necessary)? | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Was the same mode of data collection used for all subjects? | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Were the numerator(s) and denominator(s) for the parameter of interest appropriate? | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Summary on the overall risk of study | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 4 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Baalbaki, R.; Itani, L.; El Kebbi, L.; Dehni, R.; Abbas, N.; Farsakouri, R.; Awad, D.; Tannir, H.; Kreidieh, D.; El Masri, D.; et al. Association Between Smoking Hookahs (Shishas) and Higher Risk of Obesity: A Systematic Review of Population-Based Studies. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2019, 6, 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcdd6020023

Baalbaki R, Itani L, El Kebbi L, Dehni R, Abbas N, Farsakouri R, Awad D, Tannir H, Kreidieh D, El Masri D, et al. Association Between Smoking Hookahs (Shishas) and Higher Risk of Obesity: A Systematic Review of Population-Based Studies. Journal of Cardiovascular Development and Disease. 2019; 6(2):23. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcdd6020023

Chicago/Turabian StyleBaalbaki, Reem, Leila Itani, Lara El Kebbi, Rawan Dehni, Nermine Abbas, Razan Farsakouri, Dana Awad, Hana Tannir, Dima Kreidieh, Dana El Masri, and et al. 2019. "Association Between Smoking Hookahs (Shishas) and Higher Risk of Obesity: A Systematic Review of Population-Based Studies" Journal of Cardiovascular Development and Disease 6, no. 2: 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcdd6020023

APA StyleBaalbaki, R., Itani, L., El Kebbi, L., Dehni, R., Abbas, N., Farsakouri, R., Awad, D., Tannir, H., Kreidieh, D., El Masri, D., & El Ghoch, M. (2019). Association Between Smoking Hookahs (Shishas) and Higher Risk of Obesity: A Systematic Review of Population-Based Studies. Journal of Cardiovascular Development and Disease, 6(2), 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcdd6020023