Platelet-to-Lymphocyte and Glucose-to-Lymphocyte Ratios as Prognostic Markers in Hospitalized Patients with Acute Coronary Syndrome

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Sample and Ethics

2.2. Definitions and Study Endpoint

2.3. Follow-Up Procedures

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Roth, G.A.; Huffman, M.D.; Moran, A.E.; Feigin, V.; Mensah, G.A.; Naghavi, M.; Murray, C.J. Global and regional patterns in cardiovascular mortality from 1990 to 2013. Circulation 2015, 132, 1667–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikhgholami, S.; Ebadifardazar, F.; Rezapoor, A.; Tajdini, M.; Salarifar, M. Social and economic costs and health-related quality of life in patients with acute coronary syndrome: Results from a cohort study. Value Health Reg. Issues 2021, 24, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradshaw, P.J.; Ko, D.T.; Newman, A.M.; Donovan, L.R.; Tu, J.V. Validity of the GRACE (Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events) acute coronary syndrome prediction model for six month post-discharge death in an independent data set. Heart 2006, 92, 905–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrow, D.A.; Antman, E.M.; Charlesworth, A.; Cairns, R.; Murphy, S.A.; de Lemos, J.A.; Giugliano, R.P.; McCabe, C.H.; Braunwald, E. TIMI risk score for ST-elevation myocardial infarction: A convenient, bedside, clinical score for risk assessment at presentation: An Intravenous nPA for Treatment of Infarcting Myocardium Early II trial substudy. Circulation 2000, 102, 2031–2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Ma, G.; Tao, Z. The association of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio with cardiovascular and all-cause mortality among the metabolic syndrome population. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2024, 24, 594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gager, G.M.; Biesinger, B.; Hofer, F.; Winter, M.-P.; Hengstenberg, C.; Jilma, B.; Eyileten, C.; Postula, M.; Lang, I.M.; Siller-Matula, J.M. Interleukin-6 level is a powerful predictor of long-term cardiovascular mortality in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Vasc. Pharmacol. 2020, 135, 106806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, D.I.; Fu, R.; Freeman, M.; Rogers, K.; Helfand, M. C-reactive protein as a risk factor for coronary heart disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009, 150, 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvagno, G.L.; Pavan, C. Prognostic biomarkers in acute coronary syndrome. Ann. Transl. Med. 2016, 4, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, S.; Kannan, S.; Khanna, P.; Singh, A.K. Role of platelet-to-lymphocyte count ratio (PLR), as a prognostic indicator in COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Med. Virol. 2022, 94, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, J.; Zhang, H.; Wang, F.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, D.; Wang, H.; Shi, T.; Yang, S.; Yang, F.; Chen, L. The Glucose-to-Lymphocyte Ratio Predicts All-cause Mortality and Cardiovascular Mortality in ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction Patients: A Retrospective Study. Rev. Cardiovasc. Med. 2025, 26, 26065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afari, M.E.; Bhat, T. Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (NLR) and cardiovascular diseases: An update. Expert Rev. Cardiovasc. Ther. 2016, 14, 573–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heshmat-Ghahdarijani, K.; Sarmadi, V.; Heidari, A.; Marvasti, A.F.; Neshat, S.; Raeisi, S. The neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio as a new prognostic factor in cancers: A narrative review. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1228076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thygesen, K.; Alpert, J.S.; Jaffe, A.S.; Chaitman, B.R.; Bax, J.J.; Morrow, D.A.; White, H.D.; Executive Group on behalf of the Joint European Society of Cardiology (ESC)/American College of Cardiology (ACC)/American Heart Association (AHA)/World Heart Federation (WHF). Task Force for the Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction Fourth Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction. Circulation 2018, 138, e618–e651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Medical Association. WMA Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 2013, 310, 2191–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd Razali, N.; Bee Wah, Y. Power Comparisons of Shapiro-Wilk, Kolmogorov-Smirnov, Lilliefors and Anderson-Darling Tests. J. Stat. Model Anal. 2011, 2, 21–33. [Google Scholar]

- Dudley, W.N.; Wickham, P.R.; Coombs, N. An Introduction to Survival Statistics: Kaplan-Meier Analysis. J. Adv. Pr. Oncol. 2016, 7, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croxford, R. Restricted Cubic Spline Regression: A Brief Introduction. Available online: http://pages.cs.wisc.edu/~deboor/draftspline.html (accessed on 10 March 2025).

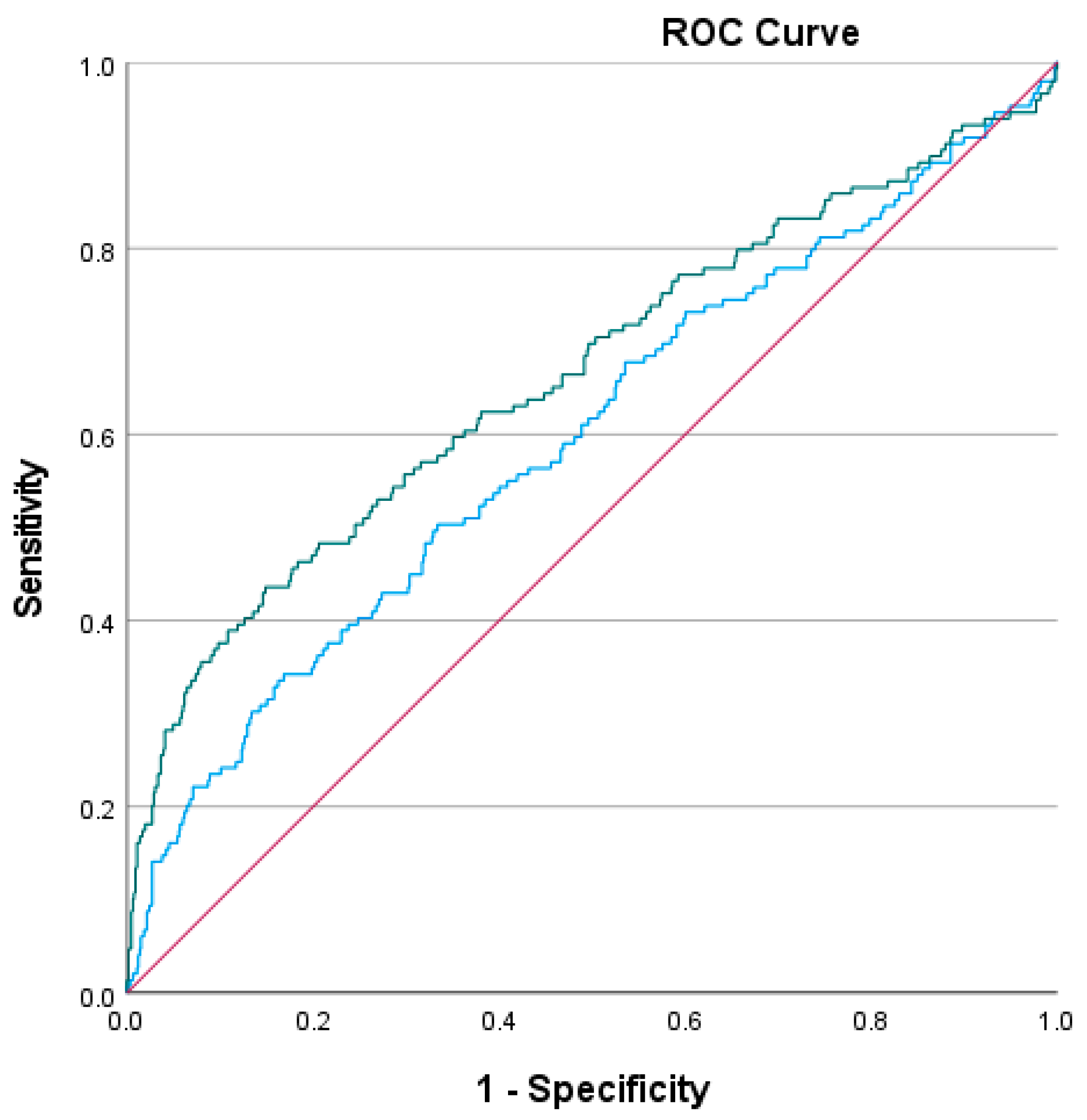

- Hanley, J.A.; McNeil, B.J. The Meaning and Use of the Area Under a Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) Curve. Radiology 1982, 143, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Wang, G.; Fan, Y.; Wan, Z.; Liu, X. Platelet to lymphocyte ratio is associated with the severity of coronary artery disease and clinical outcomes of percutaneous coronary intervention in the Chinese Han population. Exp. Ther. Med. 2017, 13, 731–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahyuni, I.; Wijaya, I.P.; Sukrisman, L.; Nasution, S.A.; Rumende, C.M. Diagnostic Accuracy of Platelet/Lymphocyte Ratio for Screening Complex Coronary Lesion in Different Age Group of Patients with Acute Coronary Syndrome. Acta Med. Indones. 2018, 50, 185–192. [Google Scholar]

- Pruc, M.; Peacock, F.W.; Rafique, Z.; Swieczkowski, D.; Kurek, K.; Tomaszewska, M.; Katipoglu, B.; Koselak, M.; Cander, B.; Szarpak, L. The Prognostic Role of Platelet-to-Lymphocyte Ratio in Acute Coronary Syndromes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 6903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oylumlu, M.; Oylumlu, M.; Arslan, B.; Polat, N.; Özbek, M.; Demir, M.; Yıldız, A.; Toprak, N. Platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio is a predictor of long-term mortality in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Adv. Interv. Cardiol. 2020, 16, 170–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, R.; Kaur, M.; Singh, J. Endothelial dysfunction and platelet hyperactivity in type 2 diabetes mellitus: Molecular insights and therapeutic strategies. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2018, 17, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paolisso, P.; Foà, A.; Bergamaschi, L.; Angeli, F.; Fabrizio, M.; Donati, F.; Toniolo, S.; Chiti, C.; Rinaldi, A.; Stefanizzi, A.; et al. Impact of admission hyperglycemia on short and long-term prognosis in acute myocardial infarction: MINOCA versus MIOCA. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2021, 20, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stalikas, N.; Papazoglou, A.S.; Karagiannidis, E.; Panteris, E.; Moysidis, D.; Daios, S.; Anastasiou, V.; Patsiou, V.; Koletsa, T.; Sofidis, G.; et al. Association of stress induced hyperglycemia with angiographic findings and clinical outcomes in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2022, 21, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Hu, X.; Elsahoryi, N.A. Association between glucose-to-lymphocyte ratio and in-hospital mortality in acute myocardial infarction patients. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0295602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serhatlioglu, F.; Cetinkaya, Z.; Yilmaz, Y. The Role of Glucose–Lymphocyte Ratio in Evaluating the Severity of Coronary Artery Disease. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 6711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Total Population (N = 853) | Elevated PLR (≥191.92) | Not-Elevated PLR (<191.92) | p-Value (PLR) | Elevated GLR (≥66.8) | Not-Elevated GLR (<66.8) | p-Value (GLR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 65 (56–75) | 67.50 (IQR 22) | 63.55 (IQR 18) | <0.001 | 68 (IQR 19) | 61 (IQR 18) | 0.003 |

| Male sex (%) | 72.3% | 17.7% | 82.3% | 0.003 | 68.5% | 22.7% | 0.003 |

| Diabetes Mellitus (%) | 27.2% | 34.3% | 24.2% | 0.006 | 40.0% | 15.7% | <0.001 |

| Hypertension (%) | 49.2% | 49.7% | 49.2% | 0.893 | 54.8% | 45.1% | 0.004 |

| Dyslipidemia (%) | 24.7% | 26.6% | 25.4% | 0.759 | 27.8% | 24.0% | 0.208 |

| Serum Creatinine (mg/dL), median (IQR) | 0.98 (0.82–1.2) | 1.56 (IQR 0.63) | 1.11 (IQR 0.32) | <0.001 | 1.06 (IQR 0.49) | 0.93 (IQR 0.29) | 0.004 |

| Statin use | 48.8 | 47.4 | 50.6 | 0.509 | 47.9 | 47.9 | 1.000 |

| Anticoagulant use | 20.6 | 17.5 | 27.0 | 0.006 | 15.6 | 24.5 | 0.001 |

| Β-blockers use | 49.2 | 45.1 | 58.0 | 0.003 | 46.3 | 49.5 | 0.392 |

| Heart Failure | 3.2 | 1.7 | 8.0 | <0.001 | 1.5 | 4.8 | 0.010 |

| Chronic Kidney Disease | 7.4 | 5.2 | 15.3 | <0.001 | 3.7 | 12.3 | <0.001 |

| Smoking status | 43.7 | 48.4 | 34.3 | 0.001 | 52.3 | 36.8 | <0.001 |

| HS-Troponin T | 116.00 (13.00–1182.00) | 94.00 (11.50–1024.00) | 385.15 (42.50–2258.00) | <0.001 | 93.00 (11.00–809.40) | 256.00 (19.50–1836.00) | <0.001 |

| Atrial Fibrillation, n (%) | 8.6% | 12.3% | 8.2% | 0.103 | 13.7% | 5.4% | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kofos, C.; Papazoglou, A.S.; Fyntanidou, B.; Samaras, A.; Stachteas, P.; Nasoufidou, A.; Apostolopoulou, A.; Karakasis, P.; Arvanitaki, A.; Bantidos, M.G.; et al. Platelet-to-Lymphocyte and Glucose-to-Lymphocyte Ratios as Prognostic Markers in Hospitalized Patients with Acute Coronary Syndrome. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2025, 12, 334. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcdd12090334

Kofos C, Papazoglou AS, Fyntanidou B, Samaras A, Stachteas P, Nasoufidou A, Apostolopoulou A, Karakasis P, Arvanitaki A, Bantidos MG, et al. Platelet-to-Lymphocyte and Glucose-to-Lymphocyte Ratios as Prognostic Markers in Hospitalized Patients with Acute Coronary Syndrome. Journal of Cardiovascular Development and Disease. 2025; 12(9):334. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcdd12090334

Chicago/Turabian StyleKofos, Christos, Andreas S. Papazoglou, Barbara Fyntanidou, Athanasios Samaras, Panagiotis Stachteas, Athina Nasoufidou, Aikaterini Apostolopoulou, Paschalis Karakasis, Alexandra Arvanitaki, Marios G. Bantidos, and et al. 2025. "Platelet-to-Lymphocyte and Glucose-to-Lymphocyte Ratios as Prognostic Markers in Hospitalized Patients with Acute Coronary Syndrome" Journal of Cardiovascular Development and Disease 12, no. 9: 334. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcdd12090334

APA StyleKofos, C., Papazoglou, A. S., Fyntanidou, B., Samaras, A., Stachteas, P., Nasoufidou, A., Apostolopoulou, A., Karakasis, P., Arvanitaki, A., Bantidos, M. G., Moysidis, D. V., Stalikas, N., Patoulias, D., Tzikas, A., Kassimis, G., Fragakis, N., & Karagiannidis, E. (2025). Platelet-to-Lymphocyte and Glucose-to-Lymphocyte Ratios as Prognostic Markers in Hospitalized Patients with Acute Coronary Syndrome. Journal of Cardiovascular Development and Disease, 12(9), 334. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcdd12090334