Abstract

Objectives: Several conditions associated with type A aortic dissection may require preoperative invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV). The current literature lacks data on this subset of patients’ prevalence and postoperative outcomes. This study aims to investigate this unexplored issue in a multicenter European registry. Methods: Data from 3735 patients included in the European Registry of Type A Aortic Dissection (ERTAAD) were the subject of this analysis. Bootstrapped Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO) logistic regression was performed for variable selection to identify key predictors of hospital death. In the second step, a multilevel multivariable logistic regression (MMLR) was carried out, given the clustered structure of the data. Results: A total of 346 (9.3%) out of 3735 patients required preoperative IMV. Compared to the non-IMV patients, patients requiring IMV had a significantly higher rate of organ malperfusion (52% vs. 35%, p < 0.001) and a higher proportion of tears in the aortic root (p = 0.048). The in-hospital mortality rate among IMV patients was 38% vs. 15% in non-IMV patients (p < 0.001), without a difference in post-discharge survival (p = 0.84). At the MMLR, patients who required IMV had 135% higher odds of in-hospital death compared to the remaining patients. IMV yielded the second highest odds in the prediction model for in-hospital mortality (OR 2.13, CI 1.60 to 2.85, p < 0.001). Among IMV patients, the extension of surgery to the aortic arch was significantly associated with increased in-hospital mortality (p < 0.001, OR 2.98). In multivariable analysis, preoperative IMV was independently associated with increased odds of in-hospital mortality. Conclusions: The need for invasive mechanical ventilation before surgical repair for type A aortic dissection is not infrequent. In this subpopulation, the in-hospital mortality rate was twofold compared to patients who did not require IMV. The awareness of the preoperative risk profile and outcomes of this subset of patients should urge surgeons to tailor the surgical strategy more appropriately to improve the immediate postoperative results.

1. Introduction

Surgical repair of acute type A aortic dissection is still associated with significant mortality rates. In this regard, large registries report early mortality rates of about 18% [1,2,3]. Many conditions such as hemodynamic instability and malperfusion syndrome may require preoperative invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV). In this setting, only two single-center studies validating the GERAADA score reported general data on this subset of patients, including prevalence and mortality rates [4,5]; however, there is a lack of specific clinical data on baseline characteristics, complications, and late follow-up of this subgroup of patients.

Thus, the current study aims to investigate this unexplored issue in a large European multicenter registry.

2. Patients and Methods

2.1. Study Population

The present analysis is based on the data of 3735 consecutive patients from the European registry of type A aortic dissection (ERTAAD). This comprises data from a multicenter, retrospective cohort including consecutive patients who received an operation for acute TAAD at 17 centers of cardiac surgery located in eight European countries (Belgium, Czech Republic, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and the United Kingdom) from January 2005 to March 2021. One center was excluded due to non-compliance with the internal protocol regarding data collection and lack of approval for submission.

The Institutional Review Board and Ethics Committee of the University Hospital Muenster (18 June 2021, diary no. 2021-368-f-S) approved this retrospective study. According to the approval, individual informed consent was not required in this retrospective analysis and therefore waived. The ERTAAD was registered in ClinicalTrials.gov with the identifier NCT04831073 (https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04831073; accessed on 29 March 2021).

2.2. Definition of Preoperative Invasive Mechanical Ventilation

In this study, preoperative invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV) was defined as mechanical ventilation via orotracheal intubation initiated prior to arrival in the operating room for surgical repair. Patients were intubated in the pre-hospital setting, emergency department, or intensive care unit, based on clinical indications such as respiratory failure, hemodynamic instability, neurological compromise, or peri-arrest conditions. No patients classified as preoperative IMV were extubated before surgery; all remained intubated until surgical intervention. Data on the precise duration of preoperative IMV were not available due to registry limitations.

2.3. Data Preprocessing

Continuous variables are presented as medians and interquartile differences. Categorical variables are shown as counts and percentages. Differences between IMV and non-IMV patients were obtained using the Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous variables, whereas the Chi-square test was applied for categorical variables when all expected cell counts were ≥5, and Fisher’s test was used for categorical variables when any expected cell count was <5.

For the correct fitting of the multilevel multivariable linear model with grouping by center, we assessed missing data for each variable across centers. Variables with less than 75% non-missing data in any center were excluded to ensure sufficient information within each group. Additionally, to maintain the model’s validity, we excluded variables with insufficient variance in at least one center. Specifically, variables that showed zero variance per outcome in any center were removed. This approach ensured that each variable included in the model had adequate variability across all centers, supporting the robustness of the multilevel analysis. Redundant variables with a correlation coefficient close to 1 were also removed to prevent multicollinearity issues in the subsequent linear models. Missing values in numeric variables were imputed using the median of the respective variable within each center. Each non-ordinal categorical variable was decomposed into multiple binary variables for each level. The ‘Year’ variable was rescaled to the range of 0 to 1; all other continuous variables were standardized to have a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1, thereby enhancing the model’s interpretability. Furthermore, we performed a bootstrapped Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO) logistic regression for variable (feature) selection to identify key predictors of hospital death and remove non-predictive variables. LASSO works by applying a penalty lambda to the size of the coefficients of the variables, shrinking less important ones to zero [6]. The bootstrapping used stratified sampling by both center and in-hospital death outcomes to ensure the preservation of covariate distributions. A LASSO grid search for optimal lambda was performed to maximize the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) area under the curve (AUC). Variables with coefficients corresponding to odds ratios between 0.9 and 1.1 were excluded, retaining only those significantly associated with hospital death. After applying the variable exclusion criteria based on insufficient variance and missing values described in Section 2, the following variables were retained for analysis: hospital death, center, onset of symptoms to surgery hours, year, age, surgery during night-time (20:00–08:00), female, eGFR CKD-EPI, arterial lactate, hypertension, pulmonary disease, cardiogenic shock requiring inotropes, Penn classification, urgency of the procedure, any malperfusion, cerebral malperfusion, peripheral malperfusion, aortic valve insufficiency, common femoral artery cannulation, tear in aortic root, tear in ascending aorta, dissection of aortic root involving non-coronary cusp, number of segments of aortic root involved, supracoronary replacement, aortic root replacement, Bentall procedure, aortic valve replacement type, type of aortic arch repair, total or partial aortic arch repair, total aortic arch repair, myocardial ischemic time, total aortic arch replacement, deep to moderate hypothermic circulatory arrest, lowest temperature during hypothermic circulatory arrest, antegrade cerebral perfusion time, antegrade cerebral perfusion, left common carotid artery antegrade, and invasive mechanical ventilation.

The final step of our analysis consisted of the multilevel multivariable logistic regression (MMLR), which is advantageous for clustered data, such as patients nested within centers. This modeling approach allows for the inclusion of random effects, such as the random intercept for the center in this study, which accounts for variability between centers and controls for potential center-specific differences that might influence outcomes. By considering both the individual- and group-level variations, multilevel models provide more accurate and generalizable estimates of predictor effects, provided that non-relevant and highly collinear variables are dropped [7]. Hence, only the LASSO-selected variables in the precedent step were included for the fitting of MMLR.

A sub-analysis including only IMV patients was conducted using a logistic regression model to identify risk factors for in-hospital mortality.

Survival estimates were generated for the long-term cohort using Kaplan–Meier analysis. Cox regression analysis, including only discharged patients, was performed to explore differences in late survival between IMV and non-IMV patients after discharge. The statistical analyses were performed using the R programming language [8] with the tidyverse package for data preprocessing [9], glmnet packages for the tuned LASSO regression [10], and the lme4 package for fitting multilevel logistic regression models [11].

In summary, variable selection for multivariable modeling was performed using bootstrapped Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO) logistic regression, with stratified sampling by center and in-hospital outcomes. This approach allowed us to identify the most relevant predictors and reduce the risk of overfitting or collinearity. Subsequently, a multilevel multivariable logistic regression (MMLR) model was constructed to account for the hierarchical, multicenter data structure and adjust for potential center-level effects. Variance inflation factors (VIFs) were calculated to confirm the absence of problematic multicollinearity among the included variables (see Supplementary Material).

3. Results

3.1. Patients’ Characteristics

A total of 346 (9.3%) out of 3735 patients required preoperative IMV. A detailed flowchart depicting inclusion and exclusion criteria and the final study population is provided in the Supplementary Material. Compared to the non-IMV patients, patients requiring IMV were older (67 vs. 64 years, p = 0.02) and had a significantly worse renal function (eGFR—CKD-EPI, 70 vs. 66 mL/min, p = 0.038) and higher preoperative arterial lactate values (p < 0.001). Patients requiring IMV had significantly higher rates of preoperative cardiac massage (20% vs. 3%, p < 0.001) and cardiogenic shock requiring inotropes (50% vs. 14%, p < 0.001). IMV patients had a significantly higher rate of organ malperfusion (52% vs. 35%, p < 0.001). Specifically, the rate of cerebral malperfusion in IMV patients was almost double that in non-IMV patients (39% vs. 20%, p < 0.001). Table 1 shows the differences at baseline between the study groups. IMV patients had a significantly higher proportion of tears in the aortic root (p = 0.048). However, root replacement was performed in those patients less frequently (25% vs. 29%, p = 0.082). Table 2 shows the intraoperative differences between the study groups.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study cohorts.

Table 2.

Operative data.

3.2. Postoperative Complications and Prediction of Mortality

IMV patients experienced significantly higher rates of global brain ischemia and hemorrhagic stroke (p < 0.001), whilst the rate of postoperative ischemic stroke was comparable (p = 0.8) between the study groups. Mesenteric ischemia and temporary dialysis were significantly higher in IMV patients (p = 0.01 and p < 0.001, respectively). Moreover, IMV patients had about a 4-fold higher incidence of venoarterial ECMO postoperatively (8.1% vs. 2.4%, p < 0.001) compared to non-IMV patients.

The mortality rate among IMV patients was 38% vs. 15% in non-IMV patients (p < 0.001). Data on postoperative outcomes are displayed in Table 3. Baseline differences between survivors and in-hospital deaths are provided in Table 4.

Table 3.

Postoperative outcomes.

Table 4.

Baseline differences between survivors and in-hospital deaths.

The bootstrapped LASSO, which maintains the original center–outcome ratio, with a lambda penalty of 0.00625, showed an ROC AUC of 0.761 ± 0.014. Patients who received invasive mechanical ventilation had 135% higher odds of in-hospital death compared to patients who were not intubated (p < 0.001, OR = 2.13, CI 1.60 to 2.85). In the prediction model, the presence of IMV yielded the highest odds for in-hospital mortality. The following further LASSO variables were identified as risk factors for in-hospital mortality: peripheral malperfusion (OR 1.40, CI 1.09 to 1.80), coronary artery bypass grafting (OR 2.54, CI 1.93 to 3.35), and urgency of the procedure (OR 1.77, CI 1.56 to 2.00) (validated definitions for the urgency of the procedure are given in Table 5 according to the study protocol [12,13]). The latter odds ratio indicates that for each one-level increase in the urgency of the procedure, the odds of in-hospital death increase by 63%. In contrast, the year of operation (OR 0.52, CI 0.37 to 0.74; for each year, the in-hospital mortality decreased by ≈3.9%) and eGFR CKD-EPI (OR 0.63, CI 0.57 to 0.69) were found to be protective. Table 6 shows the results of the LASSO and the MMLR models in detail.

Table 5.

The urgency of the procedure.

Table 6.

Results of regression analysis.

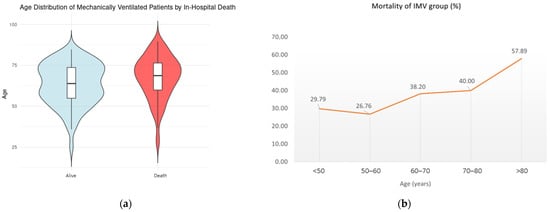

Among IMV patients, age (p = 0.028, OR 1.02, CI 1.00 to 1.05), the urgency of the procedure (p = 0.01, OR 1.65, CI 1.13 to 2.43), the intraoperative need for CABG (p = 0.007, OR 3.05, CI 1.37 to 6.95), and the extension of the surgery to the aortic arch (p < 0.001, OR 2.98, CI 1.60 to 5.62) were found to significantly increase in-hospital mortality, whereas eGFR CKD-EPI (p < 0.001, OR 0.93, CI 0.97 to 0.99) had a protective effect. Figure 1 shows the age distribution between survivors (A) and non-survivors and the trend of mortality according to increasing age among IMV patients (B).

Figure 1.

(a) Age distribution between survivors and non-survivors (violin diagram); (b) trend of mortality according to the increasing age among IMV patients.

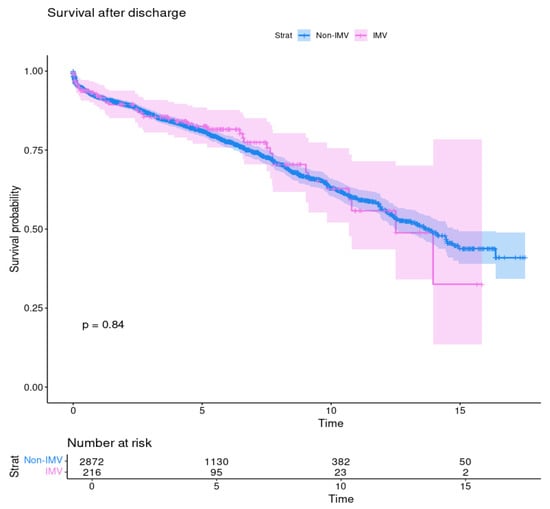

After discharge, IMV patients’ survival estimates were 92.2%, 82.5%, and 62.8% vs. 92.9%, 91.7%, and 63.1% from non-IMV patients at 1, 5, and 10 years, respectively. These rates did not differ between the study groups (p = 0.84) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Survival after discharge of patients with preoperative invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV) and without (no-IMV); p = 0.84.

Sensitivity analysis revealed variability in preoperative IMV utilization rates among different centers. Multilevel logistic regression was employed to control for these center-level variations.

4. Discussion

Patients who received preoperative IMV had 135% higher odds of in-hospital death compared to patients who did not need to be intubated. This was the highest odds reported in the prediction model for in-hospital mortality. Given this result, it is of utmost importance to consider this condition before patient referral. Hence, IMV is associated with a higher probability of root dissection and a higher rate of malperfusion, which surgeons should consider for proper tailoring of the surgical strategy. In this regard, the first difference between both groups was that there was a significantly lower rate of David procedures in the IMV group (0.6% vs. 4.3%) and the same proportion of Bentall procedures (23% in both groups) despite a significantly higher rate of tears in the aortic root (21% vs. 16%). This supports the thesis that surgeons were less aggressive in sicker patients opting for a less demanding procedure.

Another interesting finding of this study is the significantly higher mortality rate of IMV patients who received an extension of surgery to the arch (25% vs. 17%, p < 0.001, OR 2.98). This important finding should lead surgeons to be more conservative in performing distal procedures in view of the threefold increased odds of in-hospital mortality.

Regarding the incidence of IMV and the mortality rate among those patients, in the single-center study of Berezowski including 689 consecutive patients, the incidence was 6.4% and the mortality rate was 34.1%. In the study of Luehr et al. including 371 consecutive patients, the incidence of IMV was 15.1% and the mortality rate was similar to that in our cohort (37.1%). In the present study, we reported an incidence of IMV of 9.3% with a mortality of 38%. Although our mortality rates are in line with the two aforementioned studies, discrepancies regarding the incidence of IMV are likely due to many factors related to the inherent limitations of single-center observations. Those factors may include the lower number of patients and the differences in acceptance and referral of this high-risk subpopulation. Thus, given those limitations, our multicenter report offers a better overview of this subpopulation.

Considering other multicenter reports such as the GERAADA registry, in which a total of 2.137 patients were included, the need for preoperative invasive mechanical ventilation was not retained in the multivariable model for in-hospital mortality (p = 0.112) [2]. However, a later publication from the same registry with a higher number of patients (n = 2.537) integrated this variable within the GERAADA score [14]. In the report of Pollari et al. [15], in which four different scores were employed for the prediction of in-hospital mortality, the GERAADA score yielded better performance in the prediction of in-hospital mortality than the IRAD score [16]. Interestingly, the latter does not consider the preoperative need for mechanical ventilation in its calculation. Without speculating that the absence of this variable could have lowered the prediction performance of the IRAD score, we are confident that due to its important contribution to postoperative mortality, IMV should be considered in the development of future risk scoring method scores.

Interestingly, the odds ratio for the 30-day mortality in the GERAADA score was 1.95, and this was similar to our risk estimate (OR 2.20). In this regard, the current study addressed the impact on mortality through very robust statistical methods: the LASSO and the MMLR. The OR differences between the models were relatively small because the LASSO was fitted on bootstrapped data samples that maintained the same mortality ratio per center as in the non-sampled data. This approach ensured that the center-specific differences in associations between covariates and in-hospital mortality were preserved in the LASSO model, contributing to its similar baseline and effect estimates despite not explicitly modeling the hierarchical structure like the MMLR. The slightly higher intercept in the MMLR reflects the model’s adjustment for center-level clustering, which tends to moderate extreme values and capture variations across different centers. In contrast, the LASSO model does not account for this clustering, leading to a slightly lower baseline OR. These differences reflect the role of including random effects in the MMLR, which models the underlying variability between centers, while LASSO provides a more generalized estimation across the entire dataset.

Differences in the observed odds ratios for IMV between this and our previous publications can be explained by variations in statistical methodology, population inclusion criteria, and extent of risk adjustment. The present study utilized a larger multicenter cohort, bootstrapped LASSO variable selection, and multilevel modeling with center-level adjustment, which may have contributed to differences in effect estimates.

Importantly, our findings should not be interpreted as evidence that preoperative invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV) is a direct causal factor for adverse outcomes. Rather, IMV predominantly serves as a marker of increased clinical severity, reflecting profound hemodynamic instability, advanced malperfusion, or neurological compromise. This association is well-recognized in acute cardiovascular emergencies, and our results reinforce the importance of recognizing IMV as an epiphenomenon of underlying disease severity, not an independent risk modifier. Future prospective studies are needed to further elucidate the causal pathways and potential modifiable factors within this high-risk subgroup.

Furthermore, while our multicenter, adjusted analysis provides robust risk stratification, we acknowledge the potential for residual confounding inherent to observational registry studies. The associations identified should therefore be interpreted in the context of these methodological limitations.

To account for between-center variability in IMV utilization and care processes, we employed multilevel logistic regression with random intercepts for center and conducted sensitivity analyses examining center-level IMV rates. Despite these adjustments, residual selection bias may remain and should be considered when interpreting the results.

Although the association between critical illness and worse outcomes is well-recognized, our study is, to our knowledge, the first to provide multicenter, risk-adjusted quantification of mortality risk associated with preoperative IMV in acute type A aortic dissection. IMV emerged as one of the strongest independent predictors of in-hospital mortality in robust multivariable modeling. This quantitative risk stratification may support preoperative counseling, surgical planning, and the refinement of future prognostic scores for TAAD.

These findings suggest that awareness of the significantly increased mortality risk associated with preoperative IMV could assist surgeons in better tailoring surgical strategies, potentially opting for less complex and more conservative operative procedures when clinically feasible.

Given the richness of the ERTAAD dataset, future analyses should be planned to further investigate specific indications for IMV, the duration of preoperative ventilation, and time-dependent effects on outcomes, provided the necessary data granularity is available.

In conclusion, the need for IMV before surgery is the first risk factor for in-hospital mortality, and predictive scores should consider this baseline variable. Moreover, surgeons should consider this preoperative condition for proper tailoring of the surgical strategy to reduce the risk of early postoperative mortality.

5. Limitations

This study is limited by its retrospective observational design. Although we performed rigorous multivariable adjustment and utilized advanced statistical modeling to address confounding, residual confounding from unmeasured or incompletely characterized variables may still exist. In particular, the indication and precise timing of IMV initiation, as well as the severity of underlying comorbidities, were not available in all cases and thus could not be fully explored.

Additionally, the classification of patients as “preoperative IMV” may be subject to misclassification bias due to variations in documentation and practice patterns across centers.

Although preoperative pulmonary disease was uniformly defined as the use of bronchodilators and/or steroids according to the study protocol and equally distributed between both groups, the severity of pulmonary disease was not specified or captured, and therefore could not be included in the statistical analysis. Finally, data regarding the precise timing and duration of invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV) prior to surgery were not collected, which precluded a detailed analysis of its impact on outcomes and its inclusion in the regression model.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/jcdd12070239/s1: Figure S1: Patient inclusion flowchart; Table S1: Variance inflation factor (VIF) for variables included in the multivariable regression model.

Author Contributions

The first two authors contributed equally (A.M.D. and K.W.) and share the first authorship. A.M.D. and K.W.—conceptualization, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, data curation, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing. A.-I.G., G.S., F.O., T.J.D., A.R., S.P., C.R., J.B., A.F., A.P., A.G.P., J.R.L., M.P. (Marek Pol), P.K., E.M., G.G., I.V., D.P., L.F., M.R., E.Q., R.P.-G., D.D.P., Z.E.-D., H.S., G.M. (Giovanni Mariscalco), M.F., A.H., M.K., M.P. (Matteo Pettinari), S.R., T.M., L.C., G.M. (Giorgio Mastroiacovo) and T.J.—conceptualization, data curation, writing—review and editing. F.B.—conceptualization, data curation, investigation, methodology, project administration, supervision, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing. All authors reviewed the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Medical Association of Westphalia-Lippe, (18 June 2021, diary no. 2021-368-f-S). Trial Registration: ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04831073. Registered 29 March 2021.

Informed Consent Statement

According to the approval, individual informed consent was not required in this retrospective analysis and therefore waived.

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AUC | Area under the curve |

| CABG | Coronary artery bypass grafting |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| CKD | Chronic kidney disease |

| CKD-EPI | Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (formula for eGFR) |

| CPR | Cardiopulmonary resuscitation |

| ECMO | Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation |

| eGFR | Estimated glomerular filtration rate |

| ERTAAD | European registry of type A aortic dissection |

| GERAADA | German registry for acute aortic dissection type A |

| ICU | Intensive care unit |

| IMV | Invasive mechanical ventilation |

| IRAD | International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection |

| LASSO | Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator |

| MMLR | Multilevel multivariable logistic regression |

| OR | Odds ratio |

| ROC | Receiver operating characteristic |

| TAAD | Type A aortic dissection |

| V-A-ECMO | Venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation |

References

- Biancari, F.; Juvonen, T.; Fiore, A.; Perrotti, A.; Hervé, A.; Touma, J.; Pettinari, M.; Peterss, S.; Buech, J.; Dell’aquila, A.M.; et al. Current Outcome After Surgery for Type A Aortic Dissection. Ann. Surg. 2023, 278, e885–e892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conzelmann, L.O.; Weigang, E.; Mehlhorn, U.; Abugameh, A.; Hoffmann, I.; Blettner, M.; Etz, C.D.; Czerny, M.; Vahl, C.F. Mortality in patients with acute aortic dissection type A: Analysis of pre- and intraoperative risk factors from the German Registry for Acute Aortic Dissection Type A (GERAADA). Eur. J. Cardiothorac Surg. 2016, 49, e44–e52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evangelista, A.; Isselbacher, E.M.; Bossone, E.; Gleason, T.G.; Di Eusanio, M.; Sechtem, U.; Ehrlich, M.P.; Trimarchi, S.; Braverman, A.C.; Myrmel, T.; et al. Insights From the International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection: A 20-Year Experience of Collaborative Clinical Research. Circulation 2018, 137, 1846–1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luehr, M.; Merkle-Storms, J.; Gerfer, S.; Li, Y.; Krasivskyi, I.; Vehrenberg, J.; Rahmanian, P.; Kuhn-Régnier, F.; Mader, N.; Wahlers, T. Evaluation of the GERAADA score for prediction of 30-day mortality in patients with acute type A aortic dissection. Eur. J. Cardiothorac Surg. 2021, 59, 1109–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berezowski, M.; Kalva, S.; Bavaria, J.E.; Zhao, Y.; Patrick, W.L.; Kelly, J.J.; Szeto, W.Y.; Grimm, J.C.; Desai, N.D. Validation of the GERAADA score to predict 30-day mortality in acute type A aortic dissection in a single high-volume aortic centre. Eur. J. Cardiothorac Surg. 2024, 65, ezad412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tibshirani, R. Regression Shrinkage and Selection Via the Lasso. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Stat. Methodol. 1996, 58, 267–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, G. Multilevel Statistical Models; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wickham, H.; Averick, M.; Bryan, J.; Chang, W.; McGowan, L.D.A.; François, R.; Grolemund, G.; Hayes, A.; Henry, L.; Hester, J.; et al. Welcome to the Tidyverse. JOSS 2019, 4, 1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, J.; Hastie, T.; Tibshirani, R. Regularization Paths for Generalized Linear Models via Coordinate Descent. J. Stat. Softw. 2010, 33, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bates, D.; Mächler, M.; Bolker, B.; Walker, S. Fitting Linear Mixed-Effects Models Using lme4. J. Stat. Soft. 2015, 67, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biancari, F.; Dell’Aquila, A.M.; Onorati, F.; Rossetti, C.; Demal, T.; Rukosujew, A.; Peterss, S.; Buech, J.; Fiore, A.; Folliguet, T.; et al. Classification of the Urgency of the Procedure and Outcome of Acute Type A Aortic Dissection. Am. J. Cardiol. 2024, 217, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biancari, F.; Mariscalco, G.; Yusuff, H.; Tsang, G.; Luthra, S.; Onorati, F.; Francica, A.; Rossetti, C.; Perrotti, A.; Chocron, S.; et al. European registry of type A aortic dissection (ERTAAD)—rationale, design and definition criteria. J. Cardiothorac Surg. 2021, 16, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czerny, M.; Siepe, M.; Beyersdorf, F.; Feisst, M.; Gabel, M.; Pilz, M.; Pöling, J.; Dohle, D.-S.; Sarvanakis, K.; Luehr, M.; et al. Prediction of mortality rate in acute type A dissection: The German Registry for Acute Type A Aortic Dissection score. Eur. J. Cardiothorac Surg. 2020, 58, 700–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pollari, F.; Nardi, P.; Mikus, E.; Ferraro, F.; Gemelli, M.; Franzese, I.; Chirichilli, I.; Romagnoni, C.; Santarpino, G.; Nicolardi, S.; et al. Comparison of 4 mortality scores for surgical repair of type A aortic dissection: A multicentre external validation. Eur. J. Cardiothorac Surg. 2024, 65, ezae005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rampoldi, V.; Trimarchi, S.; Eagle, K.A.; Nienaber, C.A.; Oh, J.K.; Bossone, E.; Myrmel, T.; Sangiorgi, G.M.; De Vincentiis, C.; Cooper, J.V.; et al. Simple risk models to predict surgical mortality in acute type A aortic dissection: The International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection score. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2007, 83, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).