Brief Review: Racial Disparities in the Presentation and Outcomes of Patients with Thoracic Aortic Aneurysms

Abstract

1. Introduction

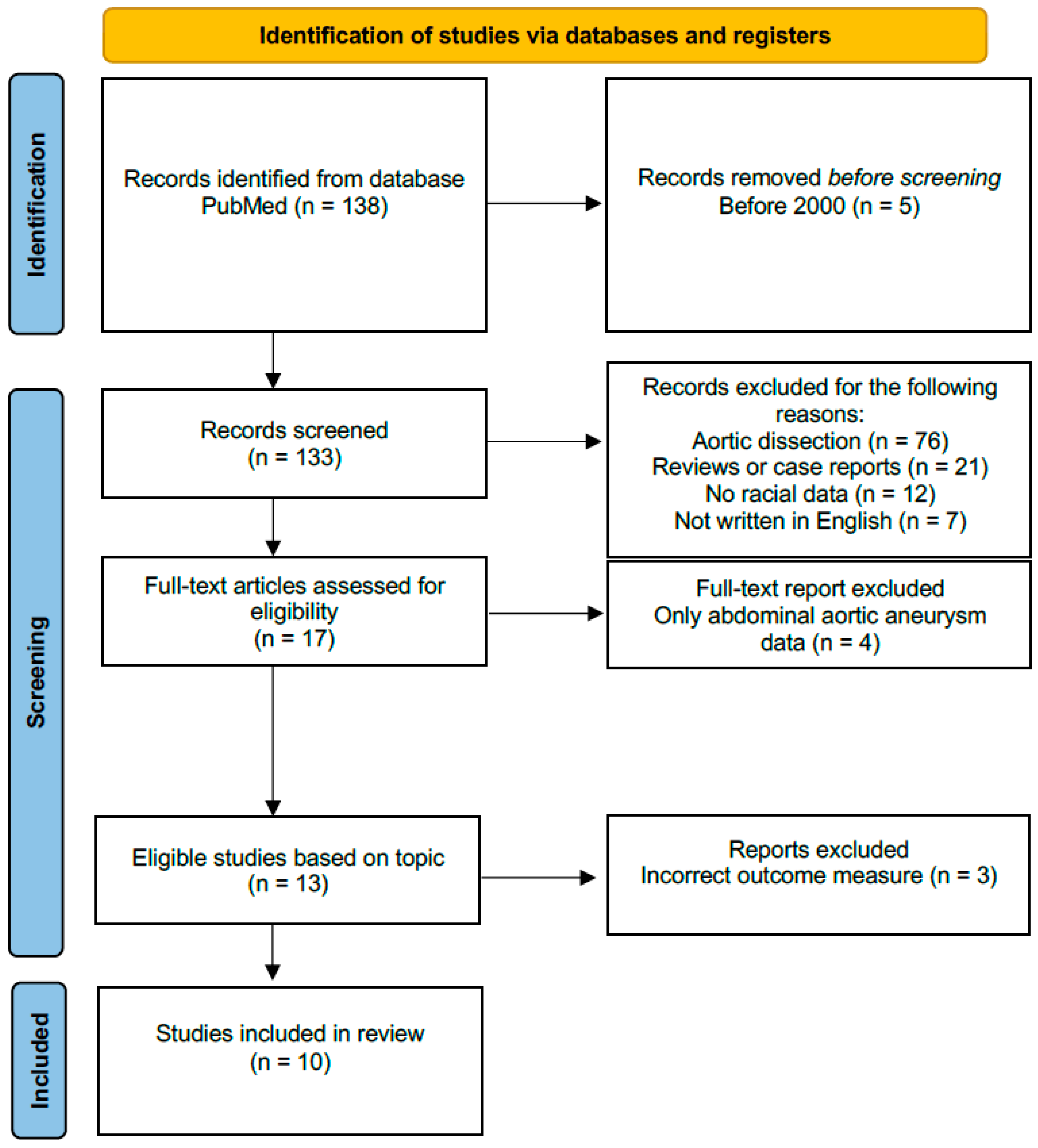

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Study Selection

2.2.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.2.2. Screening and Data Extraction

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection and Characteristics

3.2. Baseline Characteristics

3.3. Surgical Outcome

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| First Author (Year) | Study Type (Method) | Study Population(s) (Controls and Patients) | Clinical Presentation | Surgical Outcome | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Black | Black | Non-Black | Black | |||

| Goodney (2013) [10] | Retrospective cohort study Intervention: Thoracic aneurysm repair Control: Mortality Data source: Medicare claims (1999–2007) | n = 722 black patients n = 14,583 non-black patients (97% white, 1.0% Native American, 0.9% Hispanic, 0.9% Asian American, 0.1% Pacific Islander, 0.1% missing) | Older presentation (74.5 vs. 73.7; p = 0.001); 4,4% ruptured TAA (7.3% vs. 4.4%; p = 0.001); non-black patients had a higher ratio of men (56.4% vs. 43.4%; p = 0.02) | Younger presentation (74.5 vs. 73.7; p = 0.001) 7.3% ruptured TAA (7.3% vs. 4.4%; p = 0.001) Black patients had a higher Charlson comorbidity score (1.51 vs. 0.92; p = 0.001). Black patients had a higher prevalence of diabetes, heart failure, renal failure and history of malignancy (p = 0.001). | Open surgical repair: lower perioperative mortality 6.8% non-black; p < 0.001; 5-year survival: 61% p < 0.001 | Open surgical repair: higher perioperative mortality 14.4% black; p < 0.001. Operative mortality: OR 2.0; 95% CI 1.5–2.5; p < 0.0001. 5-year survival: 71%; p < 0.001. |

| Yin (2021) [11] | Retrospective cohort study Intervention: Thoracic endovascular aneurysm repair Control: 30-day mortality Data source: VQI national data registry | n = 684 black patients n = 2021 non-black patients (100% white) | 1488 aneurysms (73.6%) | More likely to undergo emergent TEVAR (27.6% vs. 19.8%; p < 0.001). More likely symptomatic (52.3% vs. 36.4%; p < 0.001). More likely to receive blood transfusion (32.1% vs. 23.6%; p < 0.001). | 30-Day Mortality: No significant difference in 30-day mortality: (3.4% vs. 4.9%; p = 0.1) | 30-Day Mortality: Following correction for operative variables, comorbidities, and demographics, black race was independently associated with 56% decrease in risk after Tevar (OR 0.44; 95% CI 0.22–0.85; p = 0.01). Postoperative Complications: No independent association (OR 0.90; 95% CI 0.68–1.17; p = 0.42). 1-year overall survival: log-rank p = 0.024. 1-year mortality Hr:0.65; 95% CI, 0.47–0.91; p = 0.01. |

| Diaz-Castrillon (2022) [12] | Retrospective cohort study Intervention: Thoracic endovascular aneurysm repair Control: In-hospital mortality Data source: Nationwide inpatient sample (NIS) 2010–2017 | n = 4959 black n = 20,301 non-black (68.1% white, 5.7% Hispanic, 6.5% others) | CAD more prevalent (34.6% (white) vs. 24.1% (black) vs. 26.8% (Hispanic) vs. 24.7% (others); p < 0.001). COPD more prevalent (28.7% vs. 15.6% vs. 15.1% vs. 16.5%; p < 0.001). TEVAR often times elective (58.8% vs. 34% vs. 48.3% vs. 48.2%; p < 0.001) | Hypertension more frequent as a comorbidity (92% (black) vs. 83% (white) vs. 85% (Hispanic) vs. 84% (others); p < 0.001). | Racial disparities do not appear to be associated with in-hospital mortality | Racial disparities do not appear to be associated with in-hospital mortality. |

| Tanious (2019) [13] | Retrospective cohort study Intervention: Thoracic endovascular aneurysm repair Control: In-hospital mortality Data source: Florida State Agency for Health Care Administration 2000–2014 | n = 1630 black n = 34,119 non-black (47.7% white, 46.0% Hispanic, 1.8% other) | Older presentation 67.42 (black) vs. 73.87 (white) vs. 73.52 (Hispanic) vs. 72.06 (other); p < 0.001 | Higher prevalence of women 31.5% (black) vs. 16.1 (white) vs. 20.2 (Hispanic) vs. 21.8 (other); p < 0.001. | Chance of in-hospital mortality: 2.5% (white), 2.8% (Hispanic), 5.1% (other); p < 0.0001 | Chance of in-hospital mortality: 4.0%; p < 0.0001 |

| Johnston (2013) [14] | Retrospective cohort study Intervention: Thoracic endovascular aneurysm repair Control: TEVAR performance based on race Data source: Nationwide inpatient sample (NIS) 2005–2008 | n = 4108 black n = 41,122 non-black (86% white, 6.2% Hispanic, 3.2% Asian or Pacific Islander, 0.8% Native American, 3.7% other) | NA | A total of 28.6% of black patients received TEVAR, whereas only 19.5% of white patients were treated with TEVAR (p < 0.001). | TEVAR performance: Odds ratio: Native American: 2.37 Black: 1.71 Hispanic: 1.70 Asian or Pacific Islander: 1.34 Other: 0.98 White (reference): 1 | Tevar performance: Odds: Black: 1.71 |

| Murphy (2013) [15] | Retrospective cohort study Intervention: Thoracic endovascular aneurysm repair Control: mortality Data source: Nationwide inpatient sample (NIS) 2001–2005 | n = 819 black n = 9738 non-black (88% white, 5.7% Hispanic, 6.8 other) | High prevalence of elective surgery: 48%; p < 0.001 | High prevalence of emergency surgery: 20%; p < 0.001. | Mortality rate: 9.8%; p < 0.001 | Mortality rate: 13.7%; p < 0.001 |

| Abdulameer (2019) [16] | Retrospective cohort study Intervention: Thoracic aneurysm rupture Control: Mortality per million Data source: U.S. National Vital Statistics System 1999–2016 | n = 104,458 total ruptures | NA | NA | Mortality/million: White women: 3.5; White men: 3.3; Asian men: 1.5; Asian women: 2.5 (p < 0.001) | Mortality/million Black women: 2.3 Black men: 2.6 (p < 0.001) |

| Vervoort (2021) [17] | Retrospective cohort study Intervention: Elective thoracic endovascular aneurysm repair Control: Reintervention and surgical outcome Data source: Vascular Quality Initiative 2009–2018 | n = 2140 black n = 40,431 Non-black (100% white) | Women sex 33.8% (23), p = 0.02; Aortic neck in mm 28.2 +/−15.8 p = 0.01; CHF: 6.0 (4) p = 0.01; Smoking history: 89.7 (61) p < 0.01 | Female sex 19.3% (212), p = 0.02; Aortic neck in mm 23.8+/−5.25 p = 0.01; CHF: 13.0 (143) p = 0.01; Smoking history: 83.1 (911) p < 0.01. | All-cause mortality: similar between groups (log-rank p = 0.25); Reintervention: white race statistically associated with reintervention; p = 0.01 | All-cause mortality: similar between groups (log-rank p = 0.25) Reintervention: Hr: 0.7; p = 0.01 |

| Ribieras (2023) [18] | Retrospective cohort study Intervention: thoracic endovascular aneurysm repair Control: All-cause mortality Data source: Global Registry for Endovascular Aortic Treatment (GREAT) 2010–2016 | n = 79 black n = 359 non-black | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: black 6.3% vs. white 20.1%; p = 0.003; Cardiac arrhythmia: black 10.1% vs. white 20.6%; p = 0.037 | Younger presentation: 62 years vs. 67 years); p < 0.001. Higher BMI 31.0 kg/m2 vs. 27.5 kg/m2); p < 0.001. Renal insufficiency: 35.4% vs. 17.8%; p = 0.001. Higher incidence of erectile dysfunction in black patients 6.3% vs. 2.0%; p = 0.047. Higher incidence of hypertension: common in black patients (100% vs. 86.5%; p = 0.034). Higher prevalence of diabetes mellitus: 18.8% vs. 4.5%; p = 0.021. | All-cause mortality: no significant difference | Complications: 34.3% vs. 17.4%; p = 0.014 Conversion to open repair: 2.9% vs. 0%; p = 0.011 Type II endoleaks: 5.7% vs. 1.0%; p = 0.040 All-cause mortality: no significant difference |

| Murphy (2010) [19] | Retrospective cohort study Intervention: Thoracic aneurysm rupture Control: Mortality Data source: U.S. National Vital Statistics System 2001–2005 | n = 104 black n = 699 non-black (93% white, 7% Hispanic) | Men: 450/650 (white), 32/49 (Hispanic); p < 0.001 | Men: 54/104 p < 0.001. | Overall mortality: 13.3% (n = 117), no differences between patients of varied ethnicity; Mortality: 12% (white), 10% (Hispanic), 19% (other); p = 303 | Overall mortality: 13.3% (n = 117), no differences between patients of varied ethnicity Mortality: 12% died; p = 0.303 |

References

- Harky, A.; Sokal, P.A.; Hasan, K.; Papaleontiou, A. The Aortic Pathologies: How Far We Understand It and Its Implications on Thoracic Aortic Surgery. Braz. J. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2021, 36, 535–549. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gouveia, E.M.R.; Silva Duarte, G.; Lopes, A.; Alves, M.; Caldeira, D.; Fernandes, E.F.R.; Pedro, L.M. Incidence and Prevalence of Thoracic Aortic Aneurysms: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Population-Based Studies. Semin. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2022, 34, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Hiratzka, L.F.; Bakris, G.L.; Beckman, J.A.; Bersin, R.M.; Carr, V.F.; Casey, D.E., Jr.; Eagle, K.A.; Hermann, L.K.; Isselbacher, E.M.; Kazerooni, E.A.; et al. 2010 ACCF/AHA/AATS/ACR/ASA/SCA/SCAI/SIR/STS/SVM guidelines for the diagnosis and management of patients with Thoracic Aortic Disease: A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines, American Association for Thoracic Surgery, American College of Radiology, American Stroke Association, Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Interventional Radiology, Society of Thoracic Surgeons, and Society for Vascular Medicine. Circulation 2010, 121, e266–e369. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Erbel, R.; Aboyans, V.; Boileau, C.; Bossone, E.; Bartolomeo, R.D.; Eggebrecht, H.; Evangelista, A.; Falk, V.; Frank, H.; Gaemperli, O.; et al. 2014 ESC Guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of aortic diseases: Document covering acute and chronic aortic diseases of the thoracic and abdominal aorta of the adult. The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Aortic Diseases of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur. Heart J. 2014, 35, 2873–2926. [Google Scholar]

- Grewal, N.; Klautz, R.J.M.; Poelmann, R.E. Intrinsic histological and morphological abnormalities of the pediatric thoracic aorta in bicuspid aortic valve patients are predictive for future aortopathy. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2023, 248, 154620. [Google Scholar]

- Grewal, N.; Gittenberger-de Groot, A.C.; Poelmann, R.E.; Klautz, R.J.; Lindeman, J.H.; Goumans, M.J.; Palmen, M.; Mohamed, S.A.; Sievers, H.-H.; Bogers, A.J.; et al. Ascending aorta dilation in association with bicuspid aortic valve: A maturation defect of the aortic wall. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2014, 148, 1583–1590. [Google Scholar]

- Grewal, N.; Gittenberger-de Groot, A.C.; Lindeman, J.H.; Klautz, A.; Driessen, A.; Klautz, R.J.M.; Poelmann, R.E. Normal and abnormal development of the aortic valve and ascending aortic wall: A comprehensive overview of the embryology and pathology of the bicuspid aortic valve. Ann. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2022, 11, 380–388. [Google Scholar]

- Crousillat, D.; Briller, J.; Aggarwal, N.; Cho, L.; Coutinho, T.; Harrington, C.; Isselbacher, E.; Lindley, K.; Ouzounian, M.; Preventza, O.; et al. Sex Differences in Thoracic Aortic Disease and Dissection: JACC Review Topic of the Week. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2023, 82, 817–827. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, J.; Coutinho, T.; Chu, M.W.A.; Ouzounian, M. Sex differences in thoracic aortic disease: A review of the literature and a call to action. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2020, 160, 656–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodney, P.P.; Brooke, B.S.; Wallaert, J.; Travis, L.; Lucas, F.L.; Goodman, D.C.; Cronenwett, J.L.; Stone, D.H. Thoracic endovascular aneurysm repair, race, and volume in thoracic aneurysm repair. J. Vasc. Surg. 2013, 57, 56–63.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, K.; AlHajri, N.; Rizwan, M.; Locham, S.; Dakour-Aridi, H.; Malas, M.B. Black patients have a higher burden of comorbidities but a lower risk of 30-day and 1-year mortality after thoracic endovascular aortic repair. J. Vasc. Surg. 2021, 73, 2071–2080.e2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Diaz-Castrillon, C.E.; Serna-Gallegos, D.; Aranda-Michel, E.; Brown, J.A.; Yousef, S.; Thoma, F.; Wang, Y.; Sultan, I. Impact of ethnicity and race on outcomes after thoracic endovascular aortic repair. J. Card. Surg. 2022, 37, 2317–2323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanious, A.; Karunathilake, N.; Toro, J.; Abu-Hanna, A.; Boitano, L.T.; Fawcett, T.; Graves, B.; Nelson, P. Racial Disparities in Endovascular Aortic Aneurysm Repair. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2019, 56, 46–51. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Johnston, W.F.; LaPar, D.J.; Newhook, T.E.; Stone, M.L.; Upchurch, G.R., Jr.; Ailawadi, G. Association of race and socioeconomic status with the use of endovascular repair to treat thoracic aortic diseases. J. Vasc. Surg. 2013, 58, 1476–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, E.H.; Stanley, G.A.; Arko, M.Z.; Davis, C.M., 3rd; Modrall, J.G.; Arko, F.R., 3rd. Effect of ethnicity and insurance type on the outcome of open thoracic aortic aneurysm repair. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2013, 27, 699–707. [Google Scholar]

- Abdulameer, H.; Al Taii, H.; Al-Kindi, S.G.; Milner, R. Epidemiology of fatal ruptured aortic aneurysms in the United States (1999–2016). J. Vasc. Surg. 2019, 69, 378–384.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vervoort, D.; Canner, J.K.; Haut, E.R.; Black, J.H.; Abularrage, C.J.; Zarkowsky, D.S.; Iannuzzi, J.C.; Hicks, C.W. Racial Disparities Associated with Reinterventions After Elective Endovascular Aortic Aneurysm Repair. J. Surg. Res. 2021, 268, 381–388. [Google Scholar]

- Ribieras, A.J.; Challa, A.S.; Kang, N.; Kenel-Pierre, S.; Rey, J.; Velazquez, O.C.; Milner, R.; Bornak, A. Race-based outcomes of thoracic aortic aneurysms and dissections in the Global Registry for Endovascular Aortic Treatment. J. Vasc. Surg. 2023, 78, 1190–1197.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, E.H.; Davis, C.M.; Modrall, J.G.; Clagett, G.P.; Arko, F.R. Effects of ethnicity and insurance status on outcomes after thoracic endoluminal aortic aneurysm repair (TEVAR). J. Vasc. Surg. 2010, 51 (Suppl. S4), 14s–20s. [Google Scholar]

- Deery, S.E.; O’Donnell, T.F.X.; Shean, K.E.; Darling, J.D.; Soden, P.A.; Hughes, K.; Wang, G.J.; Schermerhorn, M.L. Racial disparities in outcomes after intact abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. J. Vasc. Surg. 2018, 67, 1059–1067. [Google Scholar]

- Pandit, V.; Nelson, P.; Horst, V.; Hanna, K.; Jennings, W.; Kempe, K.; Kim, H. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Patients With Ruptured Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm. J. Vasc. Surg. 2020, 72, e85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asfaw, A.; Ning, Y.; Bergstein, A.; Takayama, H.; Kurlansky, P. Racial disparities in surgical treatment of type A acute aortic dissection. JTCVS Open 2023, 14, 46–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yammine, H.; Ballast, J.K.; Anderson, W.E.; Frederick, J.R.; Briggs, C.S.; Roush, T.; Madjarov, J.M.; Nussbaum, T.; Sibille, J.A.; Arko, F.R., III. Ethnic disparities in outcomes of patients with complicated type B aortic dissection. J. Vasc. Surg. 2018, 68, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diversity Data Collection in Scholarly Publishing. Available online: https://www.rsc.org/policy-evidence-campaigns/inclusion-diversity/joint-commitment-for-action-inclusion-and-diversity-in-publishing/diversity-data-collection-in-scholarly-publishing/ (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Lu, C.; Ahmed, R.; Lamri, A.; Anand, S.S. Use of race, ethnicity, and ancestry data in health research. PLoS Glob. Public Health 2022, 2, e0001060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Search | PubMed Queries—31 December 2023 | Results |

|---|---|---|

| #1 | 17,667 | |

| “Aortic Aneurysm, Thoracic” [MeSH Terms] OR “Thoracic Aortic Aneurysm *” [Title/Abstract] OR “Aneurysm, Thoracic Aortic” [Title/Abstract] OR “Aneurysm, Thoracic Aorta” [Title/Abstract] OR “Aorta Aneurysm *, Thoracic” [Title/Abstract] OR “Thoracic Aorta Aneurysm *” [Title/Abstract] OR “Thoracic Aortic Aneurysms” [Title/Abstract] OR “Thoracic Aortic Aneurysm *” [Title/Abstract] OR “Thoracic aneurysm *” [Title/Abstract] | ||

| #2 | 761,284 | |

| #3 | “ethnology” [MeSH Terms] OR “ethnicity” [MeSH Terms] OR “ethnic group *” [Title/Abstract] OR “population groups” [MeSH Terms] OR “racial groups” [MeSH Terms] OR “racial groups” [Title/Abstract] OR “ethnicity” [Title/Abstract] OR “race” [Title/Abstract] OR “Epidemiology” [MeSH Terms] OR “Epidemiology” [Title/Abstract] OR “Race-based” [Title/Abstract] OR “Inter-ethnic” [Title/Abstract] | 138 |

| ((“aortic aneurysm, thoracic ” [MeSH Terms] OR “thoracic aortic aneurysm *” [Title/Abstract] OR “aneurysm thoracic aortic” [Title/Abstract] OR “aneurysm thoracic aorta” [Title/Abstract] OR “aorta aneurysm * thoracic” [Title/Abstract] OR “thoracic aorta aneurysm *” [Title/Abstract] OR “Thoracic Aortic Aneurysms” [Title/Abstract] OR “thoracic aortic aneurysm *” [Title/Abstract] OR “thoracic aneurysm *” [Title/Abstract]) AND (“ethnology” [MeSH Terms] OR “ethnicity” [MeSH Terms] OR “ethnic group *” [Title/Abstract] OR “population groups” [MeSH Terms] OR “racial groups” [MeSH Terms] OR “racial groups” [Title/Abstract] OR “ethnicity” [Title/Abstract] OR “race” [Title/Abstract] OR “Epidemiology” [MeSH Terms] OR “Epidemiology” [Title/Abstract] OR “Race-based” [Title/Abstract] OR “Inter-ethnic” [Title/Abstract])) | ||

| Overall | 138 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bacour, N.; Theijsse, R.T.; Grewal, S.; Klautz, R.J.M.; Grewal, N. Brief Review: Racial Disparities in the Presentation and Outcomes of Patients with Thoracic Aortic Aneurysms. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2025, 12, 140. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcdd12040140

Bacour N, Theijsse RT, Grewal S, Klautz RJM, Grewal N. Brief Review: Racial Disparities in the Presentation and Outcomes of Patients with Thoracic Aortic Aneurysms. Journal of Cardiovascular Development and Disease. 2025; 12(4):140. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcdd12040140

Chicago/Turabian StyleBacour, Nora, Rutger T. Theijsse, Simran Grewal, Robert J. M. Klautz, and Nimrat Grewal. 2025. "Brief Review: Racial Disparities in the Presentation and Outcomes of Patients with Thoracic Aortic Aneurysms" Journal of Cardiovascular Development and Disease 12, no. 4: 140. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcdd12040140

APA StyleBacour, N., Theijsse, R. T., Grewal, S., Klautz, R. J. M., & Grewal, N. (2025). Brief Review: Racial Disparities in the Presentation and Outcomes of Patients with Thoracic Aortic Aneurysms. Journal of Cardiovascular Development and Disease, 12(4), 140. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcdd12040140