Definitions of Ageing According to the Perspective of the Psychology of Ageing: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

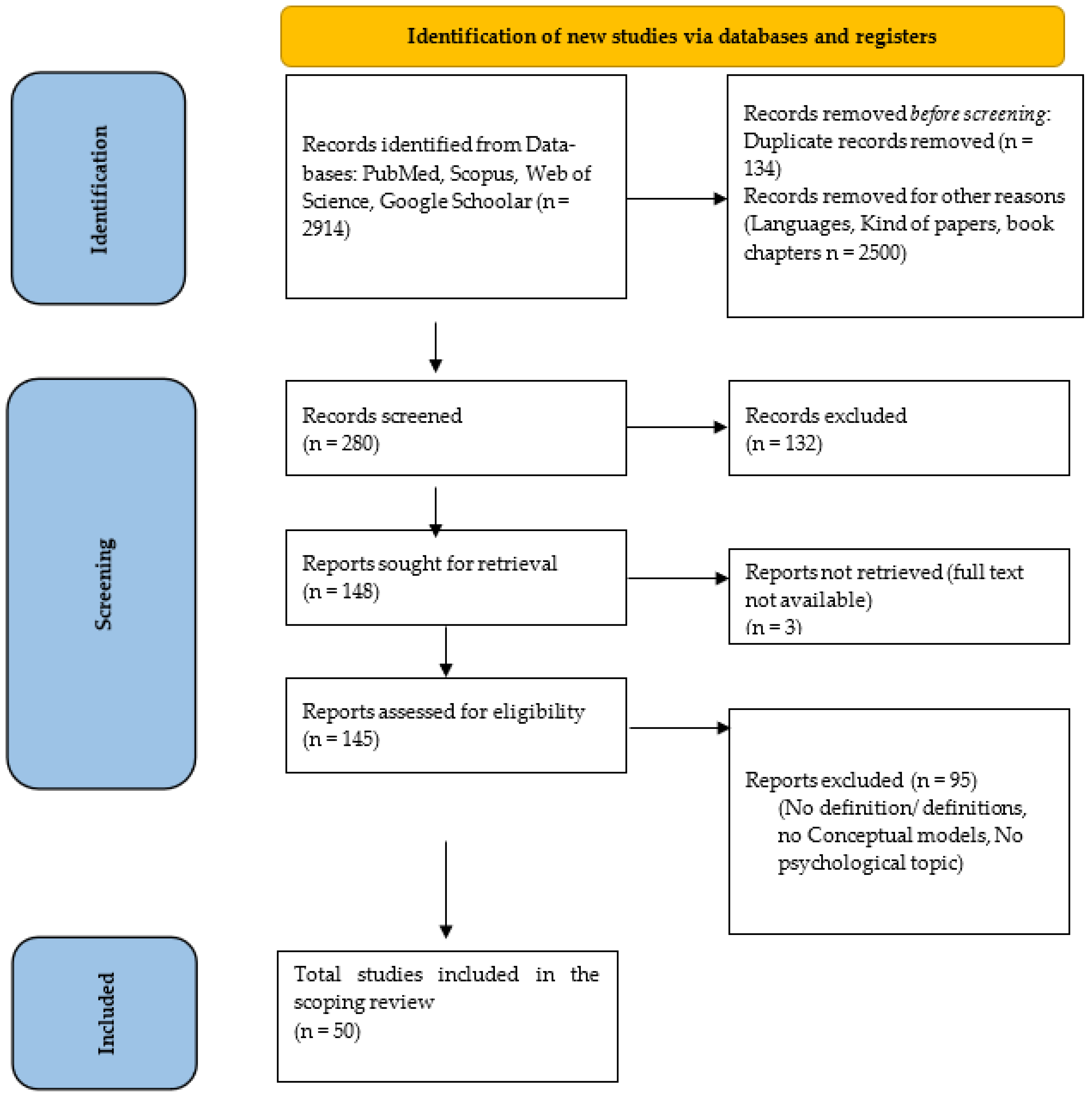

2. Methods

2.1. Protocol

2.2. Information Sources and Search Strategy

2.3. Methodological Quality Appraisal

3. Results

3.1. Successful Ageing

3.1.1. Successful Ageing Model by Havinghurst [68]

3.1.2. Successful Ageing Model by Rowe and Kahn [67,72]

3.1.3. The Communicative Ecology Model of Successful Ageing (CEMSA)

3.1.4. A Two-Factor Model of Successful Ageing

3.2. The Health, Positive and Successful Ageing

3.3. World Health Organization’s Models

3.3.1. Active Ageing

3.3.2. Healthy Ageing

3.4. Productive Ageing

3.5. Positive Ageing: The Life Span Diamond

3.6. The “Selection, Optimization, and Compensation” SOC Model

3.7. The Proactive Coping Model

3.8. Determinants and Predictors

3.9. Social–Demographic Characteristics

3.10. Education or Schooling

3.11. Physical Activity

3.12. Cognitive Functioning and Cognitive Stimulation/Remediation

3.13. Diet and Nutrition

3.14. Social/Community Engagement

3.15. Emotional Well-Being/Health

3.16. Resilience and Adaptation

3.17. Spirituality/Religiousness

3.18. Autonomy/Independence

3.19. Financial Security/Financial Independence

3.20. Engagement in Life

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pili, R.; Petretto, D.R. Genetics, lifestyles, environment and longevity: A look in a complex phenomenon. Open Access J. Gerontol. Geriatr. Med. 2017, 2, 555576. [Google Scholar]

- Dato, S.; Rose, G.; Crocco, P.; Monti, D.; Garagnani, P.; Franceschi, C.; Passarino, G. The genetics of human longevity: An intricacy of genes, environment, culture and microbiome. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2017, 165, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rothermund, K.; Englert, C.; Gerstorf, D. Explaining Variation in Individual Aging, Its Sources, and Consequences: A Comprehensive Conceptual Model of Human Aging. Gerontology 2023, 69, 1437–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Menassa, M.; Stronks, K.; Farnaz Khatami, F.; Díaz, Z.M.R.; Espinola, O.P.; Gamba, M.; Buttia, O.A.C.; Wehrli, F.; Minder, B.; Velarde, M.R.; et al. Concepts and definitions of healthy ageing: A systematic review and synthesis of theoretical models. eClinicalMedicine 2023, 56, 101821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balard, F. Old Age: Definitions, Theory and History of the Concept. In International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estebsari, F.; Dastoorpoor, M.; Khalifehkandi, Z.R.; Nouri, A.; Mostafaei, D.; Hosseini, M.; Esmaeili, R.; Aghababaeian, H. The Concept of Successful Aging: A Review Article. Curr. Aging Sci. 2020, 13, 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Petretto, D.R.; Gaviano, L.; Pili, L.; Carrogu, G.P.; Pili, R. Ageing and disability: The need of a bridge to promote wellbeing. J. Gerontol. Geriatr. Med. 2019, 4, 555648. [Google Scholar]

- Petretto, D.R.; Carrogu, G.P.; Gaviano, L.; Berti, R.; Pinna, M.; Petretto, A.D.; Pili, R. Digital determinants of health as a way to address multilevel complex causal model in the promotion of Digital health equity and the prevention of digital health inequities: A scoping review. J. Public Health Res. 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petretto, D.R.; Pili, R. Ageing and Disability According to the Perspective of Clinical Psychology of Disability. Geriatrics 2022, 7, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shadyab, A.H.; LaCroix, A.Z. Genetic factors associated with longevity: A review of recent findings. Ageing Res. Rev. 2015, 19, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montesanto, A.; De Rango, F.; Pirazzini, C.; Guidarelli, G.; Domma, F.; Franceschi, C.; Passarino, G. Demographic, genetic and phenotypic characteristics of centenarians in Italy: Focus on gender differences. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2017, 165, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltes, P.B.; Baltes, M.M. (Eds.) Psychological perspectives on successful ageing: The model of selective optimization with compensation. In Successful Ageing: Perspectives from the Behavioral Sciences; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990; pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Lachman, M.E. Development in Midlife. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2004, 55, 305–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levy, B.R. Mind Matters: Cognitive and Physical Effects of Aging Self-Stereotypes. J. Gerontol. Ser. B: Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2003, 58, P203–P211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, T.M.; Blanchard-Fields, F. (Eds.) Social Cognition and Ageing; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Passarino, G.; De Rango, F.; Montesanto, A. Human longevity: Genetics or lifestyle? It takes two to tango. Immun. Ageing 2016, 13, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amin, I. Perceptions of Successful Ageing among Older Adults in Bangladesh: An Exploratory Study. J. Cross-Cult. Gerontol. 2017, 32, 191–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boruah, A.; Barua, N.K. Successful Ageing: A Study on the Senior Teachers of Dibrugarh University, Assam. Indian J. Posit. Psychol. 2021, 12, 362–366. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Ye, M.; Kahana, E. A Self-Reliant Umbrella: Defining Successful Ageing Among the Old-Old (80+) in Shanghai. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2020, 39, 242–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiao, C.Y.; Hsiao, C.Y. Comparison of personality traits and successful ageing in older Taiwanese. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2017, 17, 2239–2246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.-N.; Choi, Y.-J.; Kim, D.-H. Association of socioeconomic status with successful ageing: Differences in the components of successful ageing. J. Biosoc. Sci. 2009, 41, 207–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Wu, W.; Jin, H.; Zhang, X.; Xue, H.; He, Y.; Xiao, S.; Jeste, D.V.; Zhang, M. Successful ageing in Shanghai, China: Definition, distribution, and related factors. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2006, 18, 551–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, S.K.; Cheng, M.Y.; Pheh, K.S. A thematic analysis of older adult’s perspective of successful ageing. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 42, 10999–11008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagalingam, J. Understanding successful ageing: A study of older Indian adults in Singapore. Care Manag. J. 2007, 8, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, T.P.; Broekman, B.F.P.; Niti, M.; Gwee, X.; Kua, E.H. Determinants of successful ageing using a multidimensional definition among Chinese elderly in Singapore. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2009, 17, 407–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanjari, N.; Sharifian Sani, M.; Hosseini Chavoshi, M.; Rafiey, H.; Mohammadi Shahboulaghi, F. Perceptions of successful ageing among Iranian elders: Insights from a qualitative study. Int. J. Ageing Hum. Dev. 2016, 83, 381–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosnes, I.; Bosnes, O.; Stordal, E.; Nordahl, H.M.; Myklebust, T.A.; Almkvist, O. Processing speed and working memory are predicted by components of successful ageing: A HUNT study. BMC Psychol. 2022, 10, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowling, A. Enhancing later life: How older people perceive active ageing? Ageing Ment. Health 2008, 12, 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowling, A.; Iliffe, S. Which model of successful ageing should be used? Baseline findings from a British longitudinal survey of ageing. Age Ageing 2006, 35, 607–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosco, T.D.; Stephan, B.C.M.; Brayne, C. Validation of an a priori, index model of successful ageing in a population-based cohort study: The successful ageing index. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2015, 27, 1971–1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domènech-Abella, J.; Perales, J.; Lara, E.; Moneta, M.V.; Izquierdo, A.; Rico-Uribe, L.A.; Mundó, J.; Haro, J.M. Sociodemographic Factors Associated with Changes in Successful Ageing in Spain: A Follow-Up Study. J. Ageing Health 2018, 30, 1244–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hörder, H.M.; Frändin, K.; Larsson, M.E.H. Self-respect through ability to keep fear of frailty at a distance: Successful ageing from the perspective of community-dwelling older people. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-Being 2013, 8, 20194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jopp, D.S.; Wozniak, D.; Damarin, A.K.; De Feo, M.; Jung, S.; Jeswani, S. How could lay perspectives on successful ageing complement scientific theory? Findings from a U.S. and a German life-span sample. Gerontologist 2015, 55, 91–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleineidam, L.; Thoma, M.V.; Maercker, A.; Bickel, H.; Mösch, E.; Hajek, A.; König, H.H.; Eisele, M.; Mallon, T.; Luck, T.; et al. What Is Successful Ageing? A Psychometric Validation Study of Different Construct Definitions. Gerontologist 2019, 59, 738–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozerska, A. The Concept of Successful Ageing from the Perspectives of Older Adults: An Empirical Typology. Kult. Eduk. 2022, 136, 215–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosraty, L.; Jylhä, M.; Raittila, T.; Lumme-Sandt, K. Perceptions by the oldest old of successful ageing, Vitality 90+ Study. J. Ageing Stud. 2015, 32, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pac, A.; Tobiasz-Adamczyk, B.; Błędowski, P.; Skalska, A.; Szybalska, A.; Zdrojewski, T.; Więcek, A.; Chudek, J.; Michel, J.-P.; Grodzicki, T. Influence of Sociodemographic, Behavioral and Other Health-Related Factors on Healthy Ageing Based on Three Operative Definitions. J. Nutr. Health Ageing 2019, 23, 862–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paúl, C.; Ribeiro, O.; Teixeira, L. Active ageing: An empirical approach to the WHO model. Curr. Gerontol. Geriatr. Res. 2012, 2012, 382972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perales, J.; Martin, S.; Ayuso-Mateos, J.L.; Chatterji, S.; Garin, N.; Koskinen, S.; Leonardi, M.; Miret, M.; Moneta, V.; Olaya, B.; et al. Factors associated with active ageing in Finland, Poland, and Spain. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2014, 26, 1363–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plugge, M. Successful ageing in the oldest old: Objectively and subjectively measured evidence from a population-based survey in Germany. Eur. J. Ageing 2021, 18, 537–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyrovolas, S.; Haro, J.M.; Mariolis, A.; Piscopo, S.; Valacchi, G.; Tsakountakis, N.; Zeimbekis, A.; Tyrovola, D.; Bountziouka, V.; Gotsis, E.; et al. Successful ageing, dietary habits and health status of elderly individuals: A k-dimensional approach within the multi-national MEDIS study. Exp. Gerontol. 2014, 60, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, A. A strategy for active ageing. Int. Soc. Secur. Rev. 2002, 55, 121–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitley, E.; Benzeval, M.; Popham, F. Population Priorities for Successful Ageing: A Randomized Vignette Experiment. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2020, 75, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernhold, Q.S. Older Parents’ and Middle-Aged Children’s Communication as Predictors of Children’s Successful Ageing. J. Lang. Soc. Psychol. 2019, 38, 305–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallardo-Peralta, L.P.; Sánchez-Moreno, E. Successful ageing in older persons belonging to the Aymara native community: Exploring the protective role of psychosocial resources. Health Psychol. Behav. Med. 2019, 7, 396–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffith, D.M.; Cornish, E.K.; Bergner, E.M.; Bruce, M.A.; Beech, B.M. “Health is the Ability to Manage Yourself Without Help”: How Older African American Men Define Health and Successful Ageing. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2018, 73, 240–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee-Bravatti, M.A.; O’Neill, H.J.; Wurth, R.C.; Sotos-Prieto, M.; Gao, X.; Falcon, L.M.; Tucker, K.L.; Mattei, J. Life style behavioral factors and integrative successful ageing among puertoricans living in the Mainland United States. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2021, 76, 1108–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, J.P. Successful ageing through the eyes of Alaska Native elders. What it means to be an elder in Bristol Bay, AK. Gerontologist 2011, 51, 540–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, S.J.; Connell, C.M.; Heeringa, S.G.; Li, L.W.; Roberts, J.S. Successful ageing in the United States: Prevalence estimates from a national sample of older adults. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2010, 65, 216–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molton, I.R.; Yorkston, K.M. Growing Older with a Physical Disability: A Special Application of the Successful Ageing Paradigm. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2017, 72, 290–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negash, S.; Smith, G.E.; Pankratz, S.; Aakre, J.; Geda, Y.E.; Roberts, R.O.; Knopman, D.S.; Boeve, B.F.; Ivnik, R.J.; Petersen, R.C. Successful ageing: Definitions and prediction of longevity and conversion to mild cognitive impairment. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2011, 19, 581–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, A.L.; Seal, D.W. Cross-Cultural Comparison of Successful Ageing Definitions between Chinese and Hmong Elders in the United States. J. Cross-Cult. Gerontol. 2014, 29, 153–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, J.R.; Baumgartner, D.A.; Austin, S.L. Healthy ageing in the far North: Perspectives and prescriptions. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2020, 79, 1735036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phelan, E.A.; Anderson, L.A.; Lacroix, A.Z.; Larson, E.B. Older Adults’ Views of “Successful Ageing”—How Do They Comparewith Researchers’ Definitions? J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2004, 52, 211–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, J.M.; Auais, M.; Belanger, E.; Phillips, S.P. Comparison of self-rated and objective successful ageing in an international cohort. Ageing Soc. 2019, 39, 1317–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tate, R.B.; Lah, L.; Cuddy, T.E. Definition of successful ageing by elderly Canadian males: The Manitoba Follow-up Study. Gerontologist 2003, 43, 735–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tate, R.B.; Loewen, B.L.; Bayomi, D.J.; Payne, B.J. The consistency of definitions of successful ageing provided by older men: The Manitoba follow-up study. Can. J. Ageing Rev. Can. Vieil. 2009, 28, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tate, R.B.; Swift, A.U.; Bayomi, D.J. Older men’s lay definitions of successful ageing over time: The Manitoba follow-up study. Int. J. Ageing Hum. Dev. 2013, 76, 297–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teater, B.; Chonody, J.M. What attributes of successful aging are important to older adults? The development of a multidimensional definition of successful aging. Soc. Work. Health Care 2020, 59, 161–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vahia, I.V.; Thompson, W.K.; Depp, C.A.; Allison, M.; Jeste, D.V. Developing a dimensional model for successful cognitive and emotional ageing. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2012, 24, 515–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, L.J.; Bond, M.J. Comparisons of the utility of researcher-defined and participant-defined successful ageing. Australas. J. Ageing 2016, 35, E7–E12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, T.; Ricciardelli, L. Successful ageing: Perceptions of adults aged between 70 and 101 years. Int. J. Ageing Hum. Dev. 2003, 56, 223–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCann Mortimer, P.; Ward, L.; Winefield, H. Successful ageing by whose definition? Views of older, spiritually affiliated women. Australas. J. Ageing 2008, 27, 200–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Ward, L.; Ziaian, T. Experiences of Chinese immigrants and Anglo-Australians ageing in Australia: A cross-cultural perspective on successful ageing. J. Health Psychol. 2010, 15, 697–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, J.; Ward, L.; Ziaian, T. Comparing definitions of successful ageing: The case of Anglo-and Chinese-Australians. E-J. Appl. Psychol. 2011, 7, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rowe, J.W.; Kahn, R.L. Human aging: Usual and successful. Science 1987, 237, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havighurst, R.J. Successful aging. Gerontologist 1961, 1, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumming, E.; Henry, W.E. Growing Old, the Process of Disengagement; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Fowler, C.; Gasiorek, J.; Giles, H. The Role of Communication in Aging Well: Introducing the Communicative Ecology Model of Successful Aging. Commun. Monogr. 2015, 82, 431–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Active Ageing: A Policy Framework. World Health Organization. 2002. Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/67215 (accessed on 12 August 2024).

- Rowe, J.W.; Kahn, R.L. Successful ageing. Gerontologist 1997, 37, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, J.W.; Kahn, R.L. Successful Ageing; Pantheon: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ryff, C.D. Beyond Ponce de Leon and life satisfaction: New directions in quest of successful ageing. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 1989, 12, 35–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depp, C.A.; Jeste, D.V. Definitions and predictors of successful aging: A comprehensive review of larger quantitative studies. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2006, 14, 6–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Havighurst, R.J.; Neugarten, B.L.; Tobin, S.S. Disengagement and Patterns of Aging. In Middle Age and Aging: A Reader in Social Psychology; Neugarten, B.L., Ed.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, CA, USA, 1968; pp. 161–172. [Google Scholar]

- Maddox, G.L. Persistence of life style among the elderly: A longitudinal study of patterns of social activity in relation to life satisfaction. Middle Age Aging Read. Soc. Psychol. 1968, 181–183. [Google Scholar]

- Baltes, M.M.; Carstensen, L.L. The Process of Successful Ageing. Ageing Soc. 1996, 16, 397–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowling, A.; Dieppe, P. What is successful ageing and who should define it? BMJ 2005, 331, 1548–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahana, E.; Kahana, B.; Kercher, K. Evaluating a model of successful aging for urban African American and white elderly. In Serving Minority Elders in the 21st Century; Wykle, M.L., Ford, A.B., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1999; pp. 287–317. [Google Scholar]

- von Faber, M.; Bootsma-van der Wiel, A.; van Exel, E.; Gussekloo, J.; Lagaay, A.M.; van Dongen, E.; Knook, D.L.; van der Geest, S.; Westendorp, R.G. Successful aging in the oldest old: Who can be characterized as successfully aged? Arch. Intern. Med. 2001, 161, 2694–2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. World Report on Ageing and Health; WHO Press: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Decision no 940/2011/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 September 2011 on the European Year for Active Ageing and Solidarity between Generations; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kerschner, H.; Pegues, J.A.M. Productive Ageing: A Quality of Life Agenda. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 1998, 98, 1445–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowling, A. The concepts of successful and positive ageing. Fam. Pract. 1993, 10, 449–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandtstädter, J.; Renner, G. Tenacious goal pursuit and flexible goal adjustment: Explication and age-related analysis of assimilative and accommodative strategies of coping. Psychol. Aging 1990, 5, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C.D. Self-perceived personality change in adulthood and aging. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1982, 42, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendricks, J.; Hendricks, C.D. Ageing in Mass Society: Myths and Realities, 3rd ed.; Little, Brown & Co.: Boston, MA, USA; Toronto, ON, Canada, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Mathewson, F.A.; Manfreda, J.; Tate, R.B.; Cuddy, T.E. The University of Manitoba Follow-up Study—An investigation of cardiovascular disease with 35 years of follow-up (1948-1983). Can. J. Cardiol. 1987, 3, 378–382. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pruchno, R.A.; Wilson-Gerderson, M.; Cartwrigh, F. A Two-Model of Successful Ageing. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2010, 65, 671–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caro, F.G.; Bass, S.A.; Chen, Y.P. Achieving a Productive Aging Society; Auburn House: Westport, Ireland, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Ballesteros, R. Positive ageing: Objective, subjective, and combined outcomes. E-J. Appl. Psychol. 2011, 7, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, R.N. Age-ism: Another Form of Bigotry. Gerontologist 1969, 9, 243–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, G.L. The need for a new medical model: A challenge for biomedicine. Science 1977, 196, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, G.E. Testing the biopsychosocial model: The ultimate challenge facing behavioral medicine? J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1982, 50, 1040–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petretto, D.R.; Pili, R.; Gaviano, L.; Matos Lòpez, C.; Zuddas, C. Active ageing and success: A brief history of conceptual models. Prev. Esp. Geriatr. Gerontol. 2016, 51, 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global Strategy and Action Plan on Ageing and Health; WHO Press: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, R.N.; Gleason, H.P. (Eds.) Productive Aging: Enhancing Vitality in Later Life; Springer Pub. Co.: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Gergen, M.M.; Gergen, K.J. Positive Ageing: Reconstructing the Life Course. In Handbook of Girl’s and Women’s Psychological Health; Academia Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2006; pp. 416–426. [Google Scholar]

- Kahana, E.; Kahana, B. Conceptual and empirical advances in understanding aging well through proactive adaptation. In Adulthood and Aging: Research on Continuities and Discontinuities; Bengtson, V.L., Ed.; Springer Publishing Company: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1996; pp. 18–40. [Google Scholar]

- Kahana, E.; Kahana, B. Successful aging among people with HIV/AIDS. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2001, 54 (Suppl. S1), S53–S56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carstensen, L.L. Social and emotional patterns in adulthood: Support for socioemotional selectivity theory. Psychol. Ageing 1992, 7, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, M.; Knoefel, J. (Eds.) Clinical Neurology of Aging; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Albert, M.S. How does education affect cognitive function? Ann. Epidemiol. 1995, 5, 76–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chodzko-Zajko, W.J.; Proctor, D.N.; Singh, M.A.; Minson, C.T.; Nigg, C.R.; Salem, G.J.; Skinner, J.S. American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Exercise and physical activity for older adults. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2009, 41, 1510–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geda, Y.E.; Roberts, R.O.; Cerhan, J.R.; Knopman, D.S.; Cha, R.H.; Christianson, T.J.; Pankratz, V.S.; Ivnik, R.J.; Boeve, B.F.; O’Connor, H.M.; et al. Physical exercise, ageing, and mild cognitive impairment: A population-based study. Arch. Neurol. 2010, 67, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petretto, D.R.; Pili, R. Longevity. In Lifestyles and Eating: The Importance of Education; Unica Press: Cagliari, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Crowther, M.R.; Parker, M.R.; Achenbaum, W.A.; Larimore, W.L.; Koenig, H.G. Rowe and Kahn’s Model of Successful Aging Revisited: Positive Spirituality—The Forgotten Factor. Gerontologist 2002, 42, 613–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, M.W. Successful aging. Gerontologist 1998, 38, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahana, E.; Kahana, B.; Kercher, K. Emerging lifestyles and proactive options for successful ageing. In Emerging Lifestyles and Proactive Options for Successful Ageing; Springer Publishing Company: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2003; pp. 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, R.N. The life review: An interpretation of reminiscence in the aged. Generations 1980, 4, 8–13. [Google Scholar]

- Birren, J.E.; Schaie, K.W. (Eds.) Handbook of the Psychology of Ageing; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Birren, J.E.; Cunningham, W.R. Research on the psychology of ageing: Principles, concepts, and theory. In Handbook of the Psychology of Ageing, 2nd ed.; Birren, J.E., Schaie, K.W., Eds.; Van Nostrand Reinhold: New York, NY, USA, 1985; pp. 3–34. [Google Scholar]

- Kalache, A.; Keller, I. (Eds.) The International Handbook on Ageing: Current Research and Developments, 2nd ed.; Greenwood Publishing Group: Westport, CT, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kalache, A.; Kickbusch, I. (Eds.) A Global Strategy for Healthy Ageing; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen, L.L.; Mikels, J.A. At the intersection of emotion and cognition: Ageing and the positivity effect. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2005, 14, 117–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pocnet, C.; Popp, J.; Jopp, D. The power of personality in successful ageing: A comprehensive review of larger quantitative studies. Eur. J. Ageing 2020, 18, 269–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, W.J.; Peng, L.N.; Lin, M.H.; Loh, C.H.; Chen, L.K. Determinants and indicators of successful ageing associated with mortality: A 4-year population-based study. Ageing 2020, 12, 2670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, J.D. Understanding and promoting AIDS-preventive behavior: Insights from the theory of reasoned action. Health Psychol. 1992, 11, 173–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, A. A European perspective on quality of life in old age. Eur. J. Ageing 2005, 2, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montross, L.P.; Depp, C.; Daly, J.; Reichstadt, J.; Golshan, S.; Moore, D.; Sitzer, D.; Jeste, D.V. Correlates of self-rated successful aging among community-dwelling older adults. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2006, 14, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strawbridge, W.J.; Wallhagen, M.I.; Cohen, R.D. Successful aging and well-being: Self-rated compared with Rowe and Kahn. Gerontologist 2002, 42, 727–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Victor, C.R.; Bowling, A.; Bond, J.; Scambler, S.J. Loneliness, social isolation and living alone in later life. Econ. Soc. Res. Counc. 2005, 123, 1–127. [Google Scholar]

- Victor, C.; Scambler, S.; Bond, J. The Social World of Older People: Understanding Loneliness and Social Isolation in Later Life; McGraw-Hill Education: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J.; Baltes, P.B.; Freund, A.M. The measurement of personal wisdom: Development and application of a new instrument. J. Gerontol. Psychol. Sci. 2010, 65, 163–172. [Google Scholar]

- Pili, R.; Petretto, D.R. Longevità, invecchiamento e benessere. In Sfide Presenti e Future; Edizioni Aracne: Roma, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Baltes, P.B.; Smith, J. New frontiers in the future of ageing: From successful ageing of the young old to the dilemmas of the fourth age. Gerontology 2003, 49, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fries, J.F.; Crimmins, E.M. The compression of morbidity hypothesis: A review of research and prospects for the future. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2011, 39, 203–220. [Google Scholar]

- Pili, R.; Gaviano, L.; Pili, L.; Petretto, D.R. Ageing and Spinal cord injury: Some issues of analysis. Curr. Gerontol. Geriatr. Res. 2018, 2018, 4017858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berkman, L.F.; Glass, T.; Brissette, I.; Seeman, T.E. From social integration to health: Durkheim in the new millennium. Soc. Sci. Med. 2000, 51, 843–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lövdén, M.; Ghisletta, P.; Lindenberger, U. Social participation attenuates decline in perceptual speed in old and very old age. Psychol. Ageing 2005, 20, 423–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Continent | Number of Studies |

|---|---|

| America | 17 |

| Asia | 10 |

| Australia | 5 |

| Europe | 18 |

| Total | 50 |

| Authors and Years | Title | Definition/Definitions | Country | Nationality | Semantic/Terminology | Range/Sample Age | Sample Size | Analysed Variables Kind of Variables: Predictors (P) or Determinants (D) if Declared | People Perception 1/External Evaluation 2 | Gender % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Amin, 2017 [18] | Perceptions of Successful Aging (SA) among Older Adults in Bangladesh: An Exploratory Study | Successful Ageing (Rowe and Kahn, 1987) [67] | Bangladesh, Asia | Bangladeshi | Successful ageing, Aging well | 60–90 | 12 | Self-awareness; perception of themselves as old; Financial security; Family and intergenerational care; Social participation | 1 | 58.3% M 41.7% F |

| 2 | Balard, 2015 [5] | Old Age: Definitions, Theory and History of the Concept | Ageing Well (Havinghurst, 1961) [68]; Successful Ageing (Rowe and Kahn, 1987) [67]; The disengagement theory (Cumming and Henry, 1961) [69] | France, Europe | ND | Old Age, Ageing well, Successful ageing | ND | ND | Ageing: individual, biological, and social factors | 2 | ND |

| 3 | Bernhold, 2019 [45] | Older Parents’ and Middle-aged Children’s communication as predictors of children’ s successful aging | The communicative ecology model of successful aging (Fowler et al., 2015–2016) [70]; SOC Model (Baltes and Baltes, 1990) [12] | America | Different ethnicities: African America, Asian America, European, America Latina America, Multiethnic, Native America | Aging efficacy, Successful aging | 40–50 | 137 | Seven types of language and communication who predict aging efficacy and successful aging: expressing optimism, self-categorising, teasing others about their age, future caregiving preferences, remaining updated, managing being the recipient of ageism, resisting mediated images of ageism | 1 | 38% M 62% F |

| 4 | Boruah and Barua, 2021 [19] | Successful Ageing: A study on the senior Teachers of Dibrugarh University, Assam | Successful Ageing (Rowe and Kahn, 1987) [67]; Active Ageing (WHO, 1990) [71]; SOC Model (Baltes and Baltes, 1990) [12] | India, Asia | Indian | Successful Ageing | 42–66 Average 54 y | 43 | Successful Aging Scale | 1 | 81% M 19% F |

| 5 | Bosnes et al., 202 [28] | Processing speed and working memory are predicted by components of successful aging: a HUNT study | Successful Ageing (Rowe and Kahn, 1987–1997) [67,72] | Nord-Trondelag Norway, Europe | Norwegian | Successful aging, | 70–89 | 65 | Successful ageing: Age, Gender, Education, Absence of disease, High functioning, Engagement with life | 1 | 53.8% F 46.2% M |

| 6 | Bowling, 2008 [29] | Enhancing later life: How older people perceive active ageing? | Active Ageing (WHO, 2002) [71]; Successful ageing (Rowe and Kahn, 1987, 1997) [67,72] | Britain, Europe | English | Active Ageing, successful aging | 65–74 75+ | 152 127 | Definition of Active Ageing: Having/maintaining physical health and functioning, leisure and social activities, mental functioning and activity, social relationships and contacts psychological, Finances, Independence | 1 | 44% M 56% F |

| 7 | Bowling and Iliffe, 2006 [30] | Which model of successful ageing should be used? Baseline findings from a British longitudinal survey of ageing | Successful Ageing (Rowe and Kahn, 1997) [72] | London Britain, Europe | English | Successful ageing | 65–70 70–75 75–80 80+ | 341 281 207 168 | Construction of models of successful ageing based on literature: Biomedical model, Broader biomedical model, Social functionating model, Lay models | 1 | 48% F |

| 8 | Brown and Bond, 2016 [62] | Comparisons of the utility of researcher-defined and participant-defined successful ageing | Successful Ageing (Rowe and Kahn, 1987) [67] | Adelaide (Australia) | South Australian population | Successful ageing | 65–97 | 380 | Successful ageing: Absence of disease, Maintenance of physical and mental functioning, active engagement with life | 1 | 55.8% F |

| 9 | Chen et al., 2020 [20] | A self-Reliant Umbrella: Defining Successful ageing among the Old-old (80+) in Shanghai | Successful ageing (Rowe and Kahn, 1987) [67] | Shanghai, Asia | Chinese | Successful Ageing | 80–99 | 97 | Successful ageing: Self-reliance, Participating in Physical Activity, Maintaining Financial Security, Social connection, Willingly Accepting Reality | 1 | 56.7% F 43.3% M |

| 10 | Chiao and Hsiao, 2017 [21] | Comparison of personality traits and successful aging in older Taiwanese | Successful ageing (Rowe and Kahn, 1987–1997) [67,72] | Taiwan, Asia | Taiwanese | Successful ageing | 65–99 | 174 | Successful ageing indicators and personality trait | 1 | 62.1% F 37.9% M |

| 11 | Cosco et al., 2015 [31] | Validation of an a priori, index model of successful aging in a population-based cohort study: the successful aging index | Successful ageing (Rowe and Kahn, 1987) [67] | England, Wales, Europe | British, Welsh | Successful ageing | 65+ | 740 | Successful Aging Index: Engagement, Personal resources, Cognitive functioning, activities of daily living, Instrumental activities of daily living | 1 | 64.2% F |

| 12 | Domenèch-Abella et al., 2018 [32] | Socio-demographic factors associated with changes in successful aging in Spain: a follow-up study | Successful ageing (Rowe and Kahn, 1998) [73] | Spain, Europe | Spanish | Successful ageing | 50–99 | 3625 | Indicators of the distinct. SA model: Biomedical, psychosocial, Rowe e Kahn; complete model of SA that included all those indicators | 2 | 53.7% F 46.3% M |

| 13 | Gallardo-Peralta and Sanchez-Moreno, 2019 [46] | Successful ageing in older persons belonging to the Aymara native community: exploring the protective role of psychosocial resources | Successful ageing (Rowe and Kahn, 1987) [67] | Chile, America | Aymara ethnicity | Successful Ageing | 60+ | 232 | Successful Ageing variable: SAI Successful Ageing Inventory, Community support; Quality of life, Religiousness/spirituality, Mental health, Main health problems | 1 | 65% F 35% M |

| 14 | Griffith et al., 2017 [47] | Health is the ability to manage yourself without help: how older African American Men define health and successful aging | Successful ageing (Rowe and Kahn, 1997) [72] | Nashville, America | African Americans | Successful ageing | 55–76 | 22 | Rowe e Kahn variables of SA: Autonomy, Functional ability, Imperative to Health, Adherence to Self-care, Definition and social determinants of health | 1 | 100% M |

| 15 | Horder et al., 2013 [33] | Self-respect through ability to keep fear of frailty at a distance: Successful ageing from the perspective of community-dwelling older people | Successful Ageing (Rowe and Kahn, 1997) [72]; SOC Model (Baltes and Baltes, 1990 [12] | Western Sweden, Europe | Swedes | Successful ageing | 77–90 | 24 | Categories to analysed SA: Having sufficient bodily resources for security and opportunities, Structures that promote security and opportunity, Feeling valuable in relation to outside world, choosing gratitude instead of worries | 1 | 37.5% F 62.5% M |

| 16 | Jang et al., 2009 [22] | Association of socioeconomic status with successful ageing: differences in the components of successful ageing | Successful ageing (Rowe and Kahn, 1997) [72]; SOC Model (Baltes and Baltes, 1990) [12] | Seoul, Korea, Asia | Korean | Successful Ageing | 65–103 | 1825 | Four components of SA: Physical function, mental function, social function, subjective well-being | 2 | 64.6% F 35.4% M |

| 17 | Jopp et al., 2015 [34] | How could Lay Perspective on successful aging complement Scientific theory? Findings from a US and German life-span sample | Successful ageing (Rowe and Kahn, 1997); Ryff (1989) [74]; Baltes and Baltes, (1990) [12]; Depp and Jeste (2006) [75] | Germany Europe, America | American, German | Successful aging, Usual aging, Robust aging, Laypersons’ Perspectives on Successful Aging | 15–96 | 306 | Determinants of Successful Aging: Health, Social resources, Activities/interests, Virtues, Attitudes, Beliefs, Well-Being, Life management, Financial resources, Independence, Aging as topic, meaning in life | 2 | ND |

| 18 | Kleineidam et al., 2019 [35] | What is Successful Aging? A psychometric validation study of different construct definitions | Successful Ageing (Rowe and Kahn 1987–1997) [67,72] | Germany, Europe | German | Successful ageing, Subjective successful aging | 75+ | 2478 | SA operationalisation: Physiological health, well-being; social engagement SA as a multi-dimensional construct | 2 | 66% F |

| 19 | Knight and Ricciardelli, 2003 [63] | Successful aging: perceptions of adults aged between 70 and 101 years | Successful aging (Rowe and Kahn 1987–1997) [67,72]; Disengagement theory (Havighurst, Neugarten e Tobin, 1968) [76]; Theory of gerotrascendence (Maddox, 1968) [77]; Psychological well-being (Ryff, 1989) [74] | Australia | Australian | Successful Aging; Usual aging; | 70–101 | 60 | SA components: Health, Happiness, relationships, appreciation/Values of life, Activity, longevity, Independence, Personal growth | 2 | 30% M 70% F |

| 20 | Kozerska, 2022 [36] | The concept of Successful Ageing from the perspectives of older adults: an empirical typology | Successful ageing (Rowe and Kahn, 1997) [72] | Poland, Europe | Polish | Successful ageing | 60–87 | 224 | Three dimensions of SA: Engagement, Activities, religiousness. Perception of successful ageing, Integrity, spirituality and community | 2 | 61.1% F 38.8% M |

| 21 | Lee-Bravatti et al., 2020 [48] | Lifestyle behavioral factors and integrative successful aging among Puerto Ricans living in the mainland United States | Rowe and Kahn (1987, 1997) [67,72] | Massachusetts, America | Puerto Rican | Successful aging | 45–75 | 950 | Successful ageing: life satisfaction, social participation, social functioning, psychological resources | 2 | 71.4% F |

| 22 | Lewis, 2011 [49] | Successful aging through the eyes of Alaska native elders. What it means to be an elder in Bristol Bay, ak | Successful ageing (Rowe and Kahn, 1987–1997) [67,72] | Bristol Bay Alaska, America | Alaskan | Two different perspectives: successful aging as a state of being, a condition that can be objectively measured a certain moment, successful ageing as a process of continuous adaptation | 61–93 | 26 | Four elements of SA: Emotional well-being, Community engagement, spirituality, Psychical Activities | 2 | 61.6% F |

| 23 | Li et al., 2006, [23] | Successful aging in Shanghai China: definition, distribution, and related factors | Successful ageing (Rowe and Kahn, 1987) [67]; (Havighurst, 1961) [68] | Shanghai, Asia | Chinese | Successful aging, usual or normal aging | 65+ | 1640 | Li et al. criteria of SA: cognitive function, activities of daily living, mood status, and no disability | 2 | 52.9% F |

| 24 | Low et al., 2021 [24] | A thematic analysis of older adult’s perspective of successful ageing | Successful ageing (Rowe and Kahn, 1987) [67]; (Baltes and Carstensen, 1996) [78]. | Malaysia, Asia | Malay, Chinese, Indian | Successful aging | 60–80 | 12 | SA criteria: being healthy, family relationship, financial independent, social connectedness, Being positive | 1 | 58.3% F |

| 25 | McCann Mortimer, Winfield, 2008 [64] | Successful ageing by whose definition? Views of older, spiritually affiliated woman | Successful ageing (Rowe and Kahn, 1987, 1997) [67,72] | Adelaide, Australia | Australian | Successful Ageing | 60–89 | 14 | Rowe e Kahn approach of SA | 2 | 100% F |

| 26 | McLaughlin et al., 2010 [50] | Successful aging in the United States: Prevalence estimates from a national sample of older adults | Successful ageing (Rowe and Kahn, 1987, 1997) [67,72] | United State, America | American | Successful ageing, Healthy aging (Depp and Jeste, 2006) [75] | 65+ | 5177 in 1998 5038 in 2000 5183 in 2002 5414 in 2004 | Rowe and Kahn criteria of SA: Active engagement, High cognitive and physical functioning, no major disease | 2 | 59.9% F 40.1% M |

| 27 | Molton and Yorkston, 2016 [51] | Growing older with a physical disability: A special application of the successful aging paradigm | Successful ageing (Rowe and Kahn, 1987–1997) [67,72]; Psychosocial approaches of SA (Bowling and Dieppe, 2005) [79]; (Baltes and Baltes, 1990) [12] | United State, America | American | Successful ageing | 45–80 | 49 | Criteria SA: Resilience and adaptation, Autonomy, social connectedness, physical health | 1 | 40.9% M 59.1% F |

| 28 | Nagalingam, 2007 [25] | Understanding successful aging: a study of older Indian adults in Singapore | Successful ageing (Rowe and Kahn 1998) [72] Stress-theory based model of SA; proactive model (Kahana and Kercher, 1999) [80] | Singapore, Asia | Indian | Successful ageing | 60–85 | 32 | Successful ageing determinates in India: Be satisfied in life, high role of activity and educational status Criteria of SA analysed: health status, Life satisfaction, Religion, engagement with life, financial resources and emotional support, Intergenerational transfer and relationship | 1 | ND |

| 29 | Negash et al., 2011 [52] | Successful aging: definitions and prediction of longevity and conversion to mild cognitive impairment | Successful ageing (Rowe and Kahn, 1987) [67] | America | American | Successful and usual ageing, Productive aging, Healthy aging | 65+ | 560 | Neuropsychological evaluation of SA into 4 domains: memory, executive faction, language, and visuospatial skills, Age, Associated memory impairment | 2 | 65.7% F |

| 30 | Ng et al., 2009 [26] | Determinants of successful aging using a multidimensional definition among Chinese elderly in Singapore | Successful ageing (Rowe and Kahn, 1997) [72] | Hong Kong and Singapore, Asia | Chinese | Successful ageing, Active aging, healthy aging | 65+ | 1281 | SA defined by specific sociodemographic, psychosocial, and behavioural determinants | 2 | 60% F 40% M |

| 31 | Nguyen and Seal, 2014 [53] | Cross-Cultural Comparison of Successful aging definitions between Chinese of Hmong elders in the United States | Successful ageing (Rowe and Kahn, 1987–1997) [67,72] | Milwaukee, America | Hmong Chinese | Successful aging | 60–101 Chinese 61–95 | 44 (Hmong 21, Chinese 23) | SA domains: Health and wellness, Happiness in old age, financial stability, social engagement, religious faith | 2 | 38.6% M 61.4% F |

| 32 | Nosraty et al., 2015 [37] | Perceptions by the oldest old of successful aging, Vitality 90+ Study | (von Faber et al., 2001) [81], Successful aging from two perspective: 1 aging as a state a of being at a certain moment (Rowe and Kahn, 1997) [67,72]; 2 successful aging as a process (Baltes and Baltes, 1990) [12] | Finland, Europe | Finnish | Successful aging, good aging for Finnish | 90–91 | 45 | Components of SA: Continuity in the process of aging, Death, harmonious and balanced life, Independence, living circumstances, physical functioning, cognitive functioning and psychological components, social functioning | 1 | 25% F 20% M |

| 33 | Pac et al., 2019 [38] | Influence of socialdemographic, behavioral and other health-related factors on healthy ageing based on three operative definitions | Successful aging (Rowe and Kahn, 1997) [72]; Healthy aging (WHO, 2016) [82] | Poland, Europe | Polish | Healthy aging, successful ageing | 65+ | 4653 | Healthy aging model based to: functional ability, intrinsic capacity, subjective well-being, health characteristics, genetic inheritance, multimorbidity, need for service, environmental factors | 2 | 51.7% M 48.3% F |

| 34 | Paul et al., 2012 [39] | Active Ageing: An empirical approach to the WHO model. | Active Ageing (WHO, 1990s, 2002) [71]; (Bowling, 2008) [29]; Successful ageing (Rowe and Kahn, 1987–1997) [67,72] | Portugal, Europe | Portuguese | Active ageing, Successful ageing, ageing well, healthy ageing, positive ageing | 55–101 | 1322 | Active Ageing Model determinants: Personal factors, Behaviour determinants, social environment, health and social services, physical environment, economic determinants Six factors: health components, psychological components, cognitive performance, biological components, social relationship, personality components | 2 | 71.1% F |

| 35 | Perales et al., 2014 [40] | Factors associated with active aging in Finland, Poland, and Spain | Active Aging (WHO 2012) [83]; Successful aging (Rowe and Kahn, 1997); Productive aging (Kerschner and Pagues, 1998) [84]; Positive ageing (Bowling, 1993) [85] | Finland, Poland and Spain, Europe | Finnish, Polish and Spanish | Active Aging | 50+ | 10800 Finland 1976; Poland 4071; Spain 4753. Final sample size was 7987 | Components of Active Aging: biomedical variables, Psychosocial variables, Social Variables, and external variables | 2 | 57.5% F 42.5% M |

| 36 | Peterson et al., 2020 [54] | Healthy ageing in the far north: perspectives | Successful ageing (Rowe and Kahn, 1987, 1997) [67,72]; SOC model (Baltes and Baltes, 1990) [12] | Alaska, America | Alaskans | Successful aging, healthy aging | 60–87 | 30 | Components: attitude/perspective, socialisation, sense of community, purpose and staying active, independence, challenges to healthy ageing | 1 | 90% F |

| 37 | Phelan et al., 2004 [55] | Older Adults’ Views of Successful aging-How do they compare with researchers’ definitions? | Successful aging (Rowe and Kahn, 1987–1997) [67,72] | America | Japanese American | Successful Aging | 65+ | 1890 | Health, physical, functional, psychological and social | 1 | 52.5% F (Jap) 57.7% F (Amer) |

| 38 | Plugge, 2021 [41] | Successful ageing in the oldest old: objectively and subjectively measured evidence from a population-based survey in Germany | Successful ageing (Rowe and Kahn, 1997) [72]; SOC model (Baltes and Carstensen, 1996) [78]; two process model (Brandtstadter and Renner, 1990) [86] | North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany, Europe | German | Successful ageing, successful life, Successfulness | 80–102 | 1863 | Objective Variants or indicator of SA: absence of disease, physical functioning, cognitive functioning, interpersonal social engagement, productive social engagement Subjective variants of SA: overall life satisfaction, positive and negative aging experience, affective well-being, valuation of life | 2 for objective criteria; 1 for subjective criteria | 50% M |

| 39 | Stewart et al., 2019 [56] | Comparison of self-rated and objective successful ageing in an international cohort | Successful ageing (Rowe and Kahn, 1987) [67] | Canada, America | Canadian, Columbian, Brazilian, Albanian | Successful aging | 65–74 | 1735 | SA analysed variables: Physical health, depression, social connectedness, resilience, site | 1 | 53% F |

| 40 | Tan et al. 2010 [65] | Experiences of Chinese immigrants and Anglo Australian ageing in Australia | Successful ageing (Havinghurst, 1961) [68]; Successful ageing model (Rowe and Kahn, 1997) [72] | Australia | Anglo and Chinese Australian | Successful ageing | 55–78 | 11 Anglo-Australian; 10 Chinese-Australian | Who do you think it means to age well? What would you make you satisfied in old age? How would ageing in Australia be different to that of your country origin? | 1 | 57.1% F |

| 41 | Tan et al., 2011 [66] | Comparing definitions of successful ageing: the case of Anglo- and Chinese Australians | Successful ageing (Rowe and Kahn, 1997) [72] | Australia | Anglo and Chinese Australians | Successful ageing, ageing well, usual ageing, | ND | 152 Anglo-Australian; 116 Chinese-Australian | SA questionnaire [55] assesses the views of older people in relation to what they perceive successful ageing, (20 statements). Successful ageing also entailed other psychological and social dimension as adjustments to change, having family and friends | 1 | ND |

| 42 | Tate et al., 2003 [57] | Definition of Successful ageing by elderly Canadian males: The Manitoba follow-up study | Different theories of SA: Rowe and Kahn (1987, 1997) [67,72]; Cuming and Henry (1961) [69]; Ryff (1982) [87]; Hendricks and Hendricks (1986) [88]; Baltes and Baltes (1990) [12] | Manitoba, Canada, America | Canadian | Successful ageing, ageing well, usual ageing | Man age average 78 | 1821 | What is your definition of successful ageing? There are 20 components themes evolved from the respondents’ definitions of successful ageing | 1 | 100% M |

| 43 | Tate et al., 2009 [58] | The consistency of definition of successful aging provided by older man: the Manitoba follow-up study | Biomedical or psycho-social models of SA [89] | Manitoba, Canada, America | Canadian | Successful ageing, ageing well | Age average 82 years | First mail 812/1254 questionnaire completed; second mail 870/1216 questionnaire completed | Coding system for definitions of successful ageing has nine main themes: health, health behaviour, having life, productivity, independence, spirituality, acceptance, social networks, life experience | 1 | 100% M |

| 44 | Tate et al., 2013 [59] | Older men’s lay definitions of successful aging over time: the Manitoba follow-up study | Two perspectives of definition of SA: clinical models (Rowe and Kahn, 1997) [72]; and psycho-social models (Baltes and Baltes, 1990) [12] | Manitoba, Canada, America | Canadian | Successful ageing, ageing well | Man average 82 years | 5898 | The SAQ question about physical, mental, and social functioning, living arrangements, retirement and successful ageing What is your definition of successful ageing? | 1 | 100% M |

| 45 | Teater and Chonody, 2020 [60] | What attributes of successful ageing are important to older adults? The development of a multidimensional definition of successful aging | Successful aging (Rowe and Kahn, 1987, 1997) [67,72] | America | ND | Successful ageing | 55–81 | 475 | SA multidimensional definition includes adapting and coping with life changes, being healthy, having a self-determinants, social relationship, mentally active, personal resources, extrinsic factors Six factors important: social, psychological, physical, financial, environmental, spiritual | 1 | 68.6% F 31.4% M |

| 46 | Tyrovolas et al., 2014 [42] | Successful aging, dietary habits and health status of elderly individuals: a k-dimensional approach within the multi-national Medis study | Biomedical models (Rowe and Kahn, 1997) [72]; and psycho-social and Lay models (Bowling and Dieppe, 2006 and Bowling and Iliffe, 2006) [30,79] | Mediterranean island, Europe | European: Italian, Sardinian, Spanish, Greek | Successful ageing | ND | 2663 | Variables of SA: biomedical, social functioning, subjective models and 10 more components as: education, financial, physical activities, BMI | 1 | ND |

| 47 | Vahia et al., 2011 [61] | Developing a dimensional model for successful cognitive and emotional aging | Successful aging (Rowe and Kahn, 1987) [67]; two factor model of SA, subjective and objective (Pruchno et al., 2010) [90] | San Diego, America | American, Caucasian. | Successful aging | 60–89 | 1948 | SA questionnaire; SA variables: Physical/general status, mental/emotional status, cognitive status, psychosocial protective factors, self-rated successful aging | 1 | 100% F |

| 48 | Walker, 2002 [43] | A Strategy for active ageing | Successful ageing (Rowe and Kahn, 1987) [67]; Theory of disengagement (Cumming and Henry, 1961) [69]; Productive ageing (Bass, Caro, Chen, 1993) [91]; Healthy ageing (WHO, 2001) [71] | European Country | European | Successful ageing, Productive ageing, Active ageing | ND | ND | Active ageing: promote public health, increase the social support, ensure social protection. Healthy lifestyles, lifelong learning, self-management | ND | ND |

| 49 | Whitley et al., 2018 [44] | Population Priorities for successful aging: a randomised vignette experiment | Successful ageing (Rowe and Kahn, 1987/1997) [67,72] | Great Britain, Europe | British | Successful ageing | Six ages groups from 35 to 75 | 2143 | Six dimensions of SA: Disease, disability, physical function, cognitive function, interpersonal engagement, productive engagement | 1 | ND |

| 50 | Zanjari et al., 2016 [27] | Perceptions of Successful ageing among Iranian Elders: insights from a qualitative study | Successful ageing (Rowe and Kahn, 1987/1997) [67,72]; SOC model (Baltes and Baltes, 1990) [12] | Iran, Asia | Iranian | Successful ageing | 60+ | 60 | Six determinants of SA: social and psychological well-being, Physical health, Spirituality, financial security, environmental and social context | 1 | 50% F |

| Age Minimum Considered | Age Sample AgeMin–AgeMax | Numbers of Papers | Sorted Papers |

|---|---|---|---|

| 15 | 15–96 | 1 | [34] |

| 35 | 35–75 | 1 | [44] |

| 40 | 40–66 | 2 | [19,45] |

| 45 | 45–80 | 2 | [48,51] |

| 50 | 50+ | 2 | [32,40] |

| 55 | 55–101 | 4 | [39,47,60,65] |

| 60 | 60–101 | 11 | [18,24,27,36,46,49,53,54,61,64] |

| 65 | 65–103 | 13 | [21,22,23,26,29,30,31,38,50,52,55,56,62] |

| 70 | 70–101 | 3 | [28,58,63] |

| 75 | 75–not specified | 1 | [35] |

| 77 | 77–90 | 1 | [33] |

| 80 | 80–not specified | 4 | [20,41,58,59] |

| 90 | 90–91 | 1 | [37] |

| ND | Not analysed | 4 | [5,42,43,66] |

| Stage of Life | Range of Years | Age Sample Age Min–Age Max | Number of Papers | Sorted Papers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adolescence to adulthood | 15–40 | 15–96 | 2 | [34,44] |

| Advanced Adulthood | 40–64 | 40–101 | 21 | [18,19,24,25,27,32,36,39,40,45,46,47,48,49,51,53,54,60,61,64,65] |

| Old Age/Elderhood | 65–79 | 65–103 | 18 | [21,22,23,26,28,29,30,31,33,35,38,50,52,55,56,58,62,63] |

| Oldest Old/Advanced Elderhood | 80+ | 80–91 | 5 | [20,37,41,58,59] |

| ND | Not analysed | 4 | [5,42,43,66] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gaviano, L.; Pili, R.; Petretto, A.D.; Berti, R.; Carrogu, G.P.; Pinna, M.; Petretto, D.R. Definitions of Ageing According to the Perspective of the Psychology of Ageing: A Scoping Review. Geriatrics 2024, 9, 107. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics9050107

Gaviano L, Pili R, Petretto AD, Berti R, Carrogu GP, Pinna M, Petretto DR. Definitions of Ageing According to the Perspective of the Psychology of Ageing: A Scoping Review. Geriatrics. 2024; 9(5):107. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics9050107

Chicago/Turabian StyleGaviano, Luca, Roberto Pili, Andrea Domenico Petretto, Roberta Berti, Gian Pietro Carrogu, Martina Pinna, and Donatella Rita Petretto. 2024. "Definitions of Ageing According to the Perspective of the Psychology of Ageing: A Scoping Review" Geriatrics 9, no. 5: 107. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics9050107

APA StyleGaviano, L., Pili, R., Petretto, A. D., Berti, R., Carrogu, G. P., Pinna, M., & Petretto, D. R. (2024). Definitions of Ageing According to the Perspective of the Psychology of Ageing: A Scoping Review. Geriatrics, 9(5), 107. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics9050107