Challenges of Dementia Care in China

Abstract

:1. Introduction

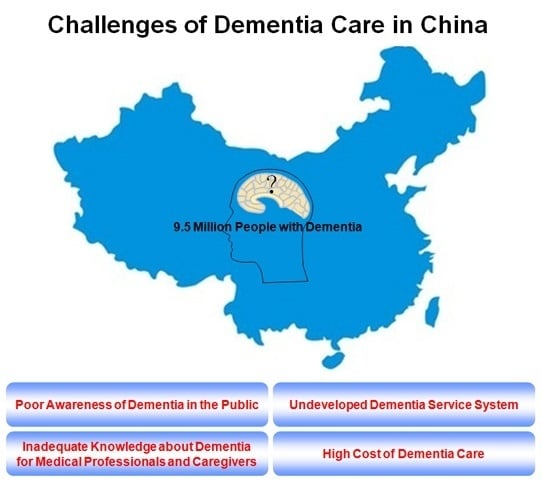

2. Dementia Prevalence in China

3. Current Challenges and Issues of Dementia Care in China

3.1. Poor Awareness of Dementia in the Public

3.2. Inadequate Knowledge about Dementia for Medical Professionals and Caregivers

3.3. Undeveloped Dementia Service System

3.4. High Cost of Dementia Care

4. Strategies to Improve Dementia Care in China

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dementia: A Public Health Priority. Available online: http://www.who.int/mental_health/publications/dementia_report_2012/en/ (accessed on 24 November 2016).

- World Alzheimer Report 2009: The Global Prevalence of Dementia. Available online: http://www.alz.co.uk/research/world-report-2009 (accessed on 24 November 2016).

- Yu, X.; Chen, S.; Chen, X.; Jia, J.; Li, C.; Liu, C.; Toumi, M.; Milea, D. Clinical management and associated costs for moderate and severe Alzheimer’s disease in urban China: A Delphi panel study. Transl. Neurodegener. 2015, 4, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boustani, M.; Schubert, C.; Sennour, Y. The challenge of supporting care for dementia in primary care. Clin. Interv. Aging 2007, 2, 631–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Alzheimer Report 2010: The Global Economic Impact of Dementia. Available online: http://www.alz.co.uk/research/world-report-2010 (accessed on 6 September 2016).

- World Alzheimer Report 2016: Improving Healthcare for People Living with Dementia. Available online: https://www.alz.co.uk/research/world-report-2016 (accessed on 24 November 2016).

- Song, Y.; Wang, J. Overview of Chinese research on senile dementia in mainland China. Ageing Res. Rev. 2010, 9 (Suppl. 1), S6–S12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.T.; Lee, H.Y.; Norton, S.; Chen, C.; Chen, H.; He, C.; Fleming, J.; Matthews, F.E.; Brayne, C. Prevalence studies of dementia in mainland china, Hong Kong and Taiwan: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e66252. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, F.; Zhang, Z.X. Epidemiological research status of dementia. Chin. J. Neurol. 2007, 40, 343–346. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Z.; Meng, C.; Dong, H.Q.; Wu, X.G.; Min, B.Q. Studies on the incidence of senile dementia in urban and rural areas of Beijing City. Chin. J. Gerontol. 2002, 22, 244–246. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.T.; Lee, H.Y.; Norton, S.; Prina, A.M.; Fleming, J.; Matthews, F.E.; Brayne, C. Period, birth cohort and prevalence of dementia in Mainland China, Hong Kong and Taiwan: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2014, 29, 1212–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.T.; Grant, W.B.; Prina, A.M.; Lee, H.Y.; Brayne, C. Nutrition and the prevalence of dementia in mainland China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan: An ecological study. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2015, 44, 1099–1106. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Albanese, E.; Li, S.; Huang, Y.; Ferri, C.P.; Yan, F.; Sousa, R.; Dang, W.; Prince, M. Chronic disease prevalence and care among the elderly in Urban and Rural Beijing, China—A 10/66 Dementia Research Group cross-sectional survey. BMC Public Health 2009, 9, 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, B.; Mao, Z.; Mei, J.; Levkoff, S.; Wang, H.; Pacheco, M.; Wu, B. Caregivers in China: Knowledge of mild cognitive impairment. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e53928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Fang, W.; Su, N.; Liu, Y.; Xiao, S.; Xiao, Z. Survey in Shanghai communities: The public awareness of and attitude towards dementia. Psychogeriatrics 2011, 11, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsiao, H.Y.; Liu, Z.; Xu, L.; Huang, Y.; Chi, I. Knowledge, Attitudes, and clinical practices for patients with dementia among mental health providers in China: City and town differences. Gerontol. Geriatr. Educ. 2015, 37, 342–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahoney, D.F.; Cloutterbuck, J.; Neary, S.; Zhan, L. African American, Chinese, and Latino family caregivers’ impressions of the onset and diagnosis of dementia: Cross-cultural similarities and differences. Gerontologist 2005, 45, 783–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, F. Caregiving stress and coping: A thematic analysis of Chinese family caregivers of persons with dementia. Dementia (Lond.) 2014, 13, 803–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, S.Y.; Lewis, F.M. Dementia friendly, dementia capable, and dementia positive: Concepts to prepare for the future. Gerontologist 2015, 55, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Country’s Mental Health Services Lacking. Available online: http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/cndy/2012-05/16/content_15302489.htm (accessed on 24 November 2016).

- Liu, J.Y.; Lai, C.; Dai, D.; Ting, S.; Choi, K. Attitudes in the management of patients with dementia: Comparison in doctors with and without special training. East Asian Arch. Psychiatry 2013, 23, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jiang, R.; Shan, X.; Zhang, R.; Wang, X. Comparison between doctors and nurses cognition about the senile dementia. Chin. J. Clin. Healthc. 2009, 12, 194–195. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, C.; Gao, L.; Chen, S.; Dong, H. Care services for elderly people with dementia in rural China: A case study. Bull. World Health Organ. 2016, 94, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- China Alzheimer’s Project—Memory360. Available online: http://www.memory360.org/en/#1 (accessed on 24 November 2016).

- Chen, R.; Hu, Z.; Chen, R.L.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, D.; Wilson, K. Determinants for undetected dementia and late-life depression. Br. J. Psychiatry 2013, 203, 203–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Boyle, L.L.; Conwell, Y.; Chiu, H.; Li, L.; Xiao, S. Dementia care in rural China. Ment. Health Fam. Med. 2013, 10, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Xiao, L.D.; Li, X.; de Bellis, A.; Ullah, S. Caregiver distress and associated factors in dementia care in the community setting in China. Geriatr. Nurs. 2015, 36, 348–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, L.D.; Wang, J.; He, G.P.; De Bellis, A.; Verbeeck, J.; Kyriazopoulos, H. Family caregiver challenges in dementia care in Australia and China: A critical perspective. BMC Geriatr. 2014, 14, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, Y.; Fan, R.; Wang, Y.M.; Kaye, A.J.; Kaye, A.D.; Bueno, F.R.; Pei, J.M. A changing healthcare system model: The effectiveness of knowledge, attitude, and skill of nursing assistants who attend senile dementia patients in nursing homes in Xi’an, China—A Questionnaire Survey. Ochsner J. 2014, 14, 328–334. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.X.; Chen, X.; Liu, X.H.; Tang, M.N.; Zhao, H.H.; Jue, Q.M.; Wu, C.B.; Hong, Z.; Zhou, B. A caregiver survey in Beijing, Xi’an, Shanghai and Chengdu: Health services status for the elderly with dementia. Acta Acad. Med. Sin. 2004, 26, 116–121. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, L.; Chen, K. Rural-urban differences in the long-term care of the disabled elderly in China. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e79955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flaherty, J.H.; Liu, M.L.; Ding, L.; Dong, B.; Ding, Q.; Li, X.; Xiao, S. China: The aging giant. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2007, 55, 1295–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, D.; Wu, X.N.; Zhang, Y.X.; Li, H.P.; Wang, W.L.; Zhang, J.P.; Zhou, L.S. Depression and social support between China’ rural and urban empty-nest elderly. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2012, 55, 564–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y. The home resident, health and care arrangements of the aging population in China: The sixth census data analysis. Jiangsu Soc. Sci. 2013, 1, 57–65. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Z.; Liu, C.; Guan, X.; Mor, V. China’s rapidly aging population creates policy challenges in shaping a viable long-term care system. Health Aff. (Millwood) 2012, 31, 2764–2773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallagher-Thompson, D.; Tzuang, Y.; Au, A.; Wang, D.; Tsien, T.; Wang, P.; Catholic, F.; Huang, Y. Families dealing with dementia: Insights from China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan. In Aging Asia: The Economic and Social Implications of Rapid Demographic Change in China, Japan, and South Korea; Karen, E., Shripad, T., Eds.; The Walter H. Shorenstein Asia-Pacific Research Center: Stanford, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; Boyle, L.L.; Conwell, Y.; Xiao, S.; Chiu, H.F. The challenges of dementia care in rural China. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2014, 26, 1059–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, S.; Dong, B.; Ding, G.; Chen, J.; Pang, W. Status quo of reception and care for patients with senile dementia in pension agencies in Chengdu. Mod. Prev. Med. 2011, 38, 482–484. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, G.; Cheng, Q.; Zhang, S.; Bai, L.; Zeng, J.; Cui, P.J.; Zhang, T.; Sun, Z.K.; Ren, R.J.; Deng, Y.L.; et al. Economic impact of dementia in developing countries: An evaluation of Alzheimer-type dementia in Shanghai, China. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2008, 15, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Keogh-Brown, M.R.; Jensen, H.T.; Arrighi, H.M.; Smith, R.D. The impact of Alzheimer’s disease on the Chinese economy. EBioMedicine 2016, 4, 184–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, Q.; Fang, H.; Liu, X.; Yuan, B.; Xu, J. Consolidating the social health insurance schemes in China: Towards an equitable and efficient health system. Lancet 2015, 386, 1484–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Long March to Universal Coverage: Lessons from China. Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/13303 (accessed on 24 November 2016).

- Feng, Z.; Zhan, H.J.; Feng, X.; Liu, C.; Sun, M.; Mor, V. An industry in the making: The emergence of institutional elder care in Urban China. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2011, 59, 738–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mould-Quevedo, J.F.; Tang, B.; Harary, E.; Kurzman, R.; Pan, S.; Yang, J.; Qiao, J. The burden of caring for dementia patients: Caregiver reports from a cross-sectional hospital-based study in China. Expert Rev. Pharmacoecon. Outcomes Res. 2013, 13, 663–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- China Statistical Yearbook 2010. Available online: http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/ndsj/2010/indexeh.htm (accessed on 24 November 2016).

- The National Five-Year Plan for Mental Health (2015–2020). Available online: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2015-06/18/content_9860.htm (accessed on 24 November 2016).

- Deepening Health Reform in China: Building High-Quality and Value-Based Service Delivery. Available online: http://www.indiaenvironmentportal.org.in/content/433080/deepening-health-reform-in-china-building-high-quality-and-value-based-service-delivery/ (accessed on 24 November 2016).

- Wu, D.; Lam, T.P. Underuse of primary care in China: The scale, causes, and solutions. J. Am. Board Fam. Med. 2016, 29, 240–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2017 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, Z.; Yang, X.; Song, Y.; Song, B.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, J.; Wang, Q.; Yu, J. Challenges of Dementia Care in China. Geriatrics 2017, 2, 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics2010007

Chen Z, Yang X, Song Y, Song B, Zhang Y, Liu J, Wang Q, Yu J. Challenges of Dementia Care in China. Geriatrics. 2017; 2(1):7. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics2010007

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Zheng, Xuan Yang, Yuetao Song, Binbin Song, Yi Zhang, Jiawen Liu, Qing Wang, and Jia Yu. 2017. "Challenges of Dementia Care in China" Geriatrics 2, no. 1: 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics2010007

APA StyleChen, Z., Yang, X., Song, Y., Song, B., Zhang, Y., Liu, J., Wang, Q., & Yu, J. (2017). Challenges of Dementia Care in China. Geriatrics, 2(1), 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics2010007