Effect of a Physio-Feedback Exercise Intervention Program on the Static Balance of Community-Dwelling Older Adults: A Clustered Randomized Controlled Trial

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Sample Size Calculation

2.3. Participants

2.3.1. Intervention Group

2.3.2. Control Group

2.4. Demographic Information

2.5. Static Balance Assessment

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

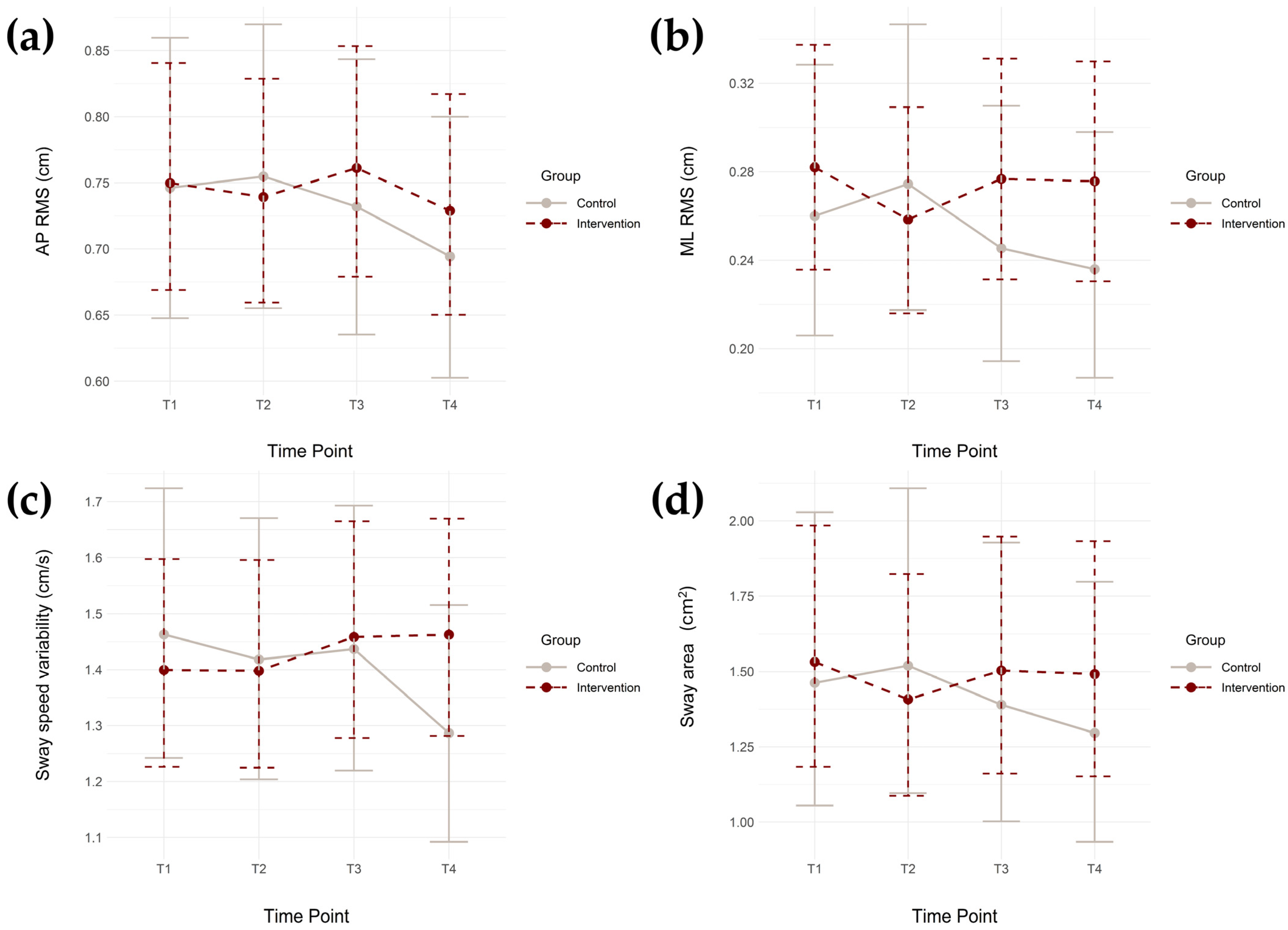

3.1. Linear Mixed Effects Models for All Static Balance Metrics

3.2. Number of Falls Among Groups

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AP | Anterior–posterior |

| COP | Center of pressure |

| ML | Medial-lateral |

| PEER | Physio-feedback Exercise Program |

| RMS | Root mean square |

References

- Florence, C.S.; Bergen, G.; Atherly, A.; Burns, E.; Stevens, J.; Drake, C. Medical costs of fatal and nonfatal falls in older adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2018, 66, 693–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunn, J.E.; Rudberg, M.A.; Furner, S.E.; Cassel, C.K. Mortality, disability, and falls in older persons: The role of underlying disease and disability. Am. J. Public Health 1992, 82, 395–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinetti, M.E.; Speechley, M.; Ginter, S.F. Risk factors for falls among elderly persons living in the community. N. Engl. J. Med. 1988, 319, 1701–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houry, D.; Florence, C.; Baldwin, G.; Stevens, J.; McClure, R. The CDC Injury Center’s response to the growing public health problem of falls among older adults. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 2016, 10, 74–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.T.; Morton, S.C.; Rubenstein, L.Z.; Mojica, W.A.; Maglione, M.; Suttorp, M.J.; Roth, E.A.; Shekelle, P.G. Interventions for the prevention of falls in older adults: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised clinical trials. Br. Med. J. 2004, 328, 680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, S.; Leland, N.E. Occupational therapy fall prevention interventions for community-dwelling older adults: A systematic review. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2018, 72, 7204190040p1–7204190040p11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, A.; Smith, B.; Lord, S.R.; Williams, M.; Baumand, A. Community-based group exercise improves balance and reduces falls in at-risk older people: A randomised controlled trial. Age Ageing 2003, 32, 407–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiamwong, L.; Xie, R.; Park, J.H.; Lighthall, N.; Loerzel, V.; Stout, J. Optimizing a technology-based body and mind intervention to prevent falls and reduce health disparities in low-income populations: Protocol for a clustered randomized controlled trial. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2023, 12, e51899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latham, N.K.; Anderson, C.S.; Lee, A.; Bennett, D.A.; Moseley, A.; Cameron, I.D. A randomized, controlled trial of quadriceps resistance exercise and vitamin D in frail older people: The Frailty Interventions Trial in Elderly Subjects (FITNESS). J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2003, 51, 291–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serra-Rexach, J.A.; Bustamante-Ara, N.; Hierro Villarán, M.; González Gil, P.; Sanz Ibáñez, M.J.; Blanco Sanz, N.; Santamaría, V.O.; Gutiérrez Sanz, N.; Marín Prada, A.B.; Gallardo, C.; et al. Short-term, light- to moderate-intensity exercise training improves leg muscle strength in the oldest old: A randomized controlled trial. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2011, 59, 594–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, C.; Ebeling, P.R.; Scott, D. Body composition and falls risk in older adults. Curr. Geriatr. Rep. 2019, 8, 210–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, V.-A.T.; Nguyen, T.N.; Nguyen, T.X.; Nguyen, H.T.T.; Nguyen, T.T.H.; Nguyen, A.T.; Pham, T.; Vu, H.T.T. Prevalence and factors associated with falls among older outpatients. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mancini, M.; Salarian, A.; Carlson-Kuhta, P.; Zampieri, C.; King, L.; Chiari, L.; Horak, F.B. ISway: A sensitive, valid and reliable measure of postural control. J. NeuroEng. Rehabil. 2012, 9, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greve, J.; Alonso, A.; Bordini, A.C.P.G.; Camanho, G.L. Correlation between body mass index and postural balance. Clinics 2007, 62, 717–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, C.A.; Ricci, N.A.; Nogueira, E.C.; Perracini, M.R. The Berg Balance Scale as a clinical screening tool to predict fall risk in older adults: A systematic review. Physiotherapy 2018, 104, 383–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omaña, H.; Bezaire, K.; Brady, K.; Davies, J.; Louwagie, N.; Power, S.; Santin, S.; Hunter, S.W. Functional Reach Test, Single-Leg Stance Test, and Tinetti Performance-Oriented Mobility Assessment for the prediction of falls in older adults: A systematic review. Phys. Ther. 2021, 101, pzab173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, W.; Ferguson, S.; Brault, S.; Craig, C. Assessing and training standing balance in older adults: A novel approach using the ‘Nintendo Wii’ Balance Board. Gait Posture 2011, 33, 303–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marques, L.T.; Rodrigues, N.C.; Angeluni, E.O.; dos Santos Pessanha, F.P.A.; da Cruz Alves, N.M.; Freire Júnior, R.C.; Ferriolli, E.; de Abreu, D.C.C. Balance evaluation of prefrail and frail community-dwelling older adults. J. Geriatr. Phys. Ther. 2019, 42, 176–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazumder, O.; Tripathy, S.; Roy, S.; Chakravarty, K.; Chatterjee, D.; Sinha, A. Postural sway based geriatric fall risk assessment using kinect. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE SENSORS, Glasgow, UK, 29 October–1 November 2017; Volume 2017, pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Johansson, J.; Jarocka, E.; Westling, G.; Nordström, A.; Nordström, P. Predicting incident falls: Relationship between postural sway and limits of stability in older adults. Hum. Mov. Sci. 2019, 66, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suarez, J.R.M.; Park, J.-H.; Thiamwong, L. Assessment of static balance metrics in community-dwelling older adults categorized using the fall risk appraisal matrix. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suarez, J.R.M.; Decker, V.B.; Park, J.-H.; Lighthall, N.R.; Dino, M.J.S.; Thiamwong, L. Directional postural sway tendencies and static balance among community-dwelling older adults with depression and without cognitive impairment. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2025, 37, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, C.; Ni, L.; Zhang, W.; Chen, C.; Lopez, J.; Zheng, H.; Thiamwong, L.; Xie, R. Effectiveness of PEER intervention on older adults’ physical activity time series using smoothing spline ANOVA. Mathematics 2025, 13, 516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suarez, J.R.; Park, J.-H.; Xie, R.; Lafontant, K.; Thiamwong, L. Effects of physio-feedback exercise program (PEER) on physical activity levels in older adults. Innov. Aging 2024, 8, 1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiamwong, L.; Stout, J.R.; Sole, M.L.; Ng, B.P.; Yan, X.; Talbert, S. Physio-Feedback and Exercise Program (PEER) improves balance, muscle strength, and fall risk in older adults. Res. Gerontol. Nurs. 2020, 13, 289–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Census Bureau. Historical Poverty Thresholds. 2022. Available online: https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/income-poverty/historical-poverty-thresholds.html (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Minor, B.L.; Elliott, V.; Fernandez, M.; O’Neal, L.; McLeod, L.; Delacqua, G.; Delacqua, F.; Kirby, J.; et al. The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners. J. Biomed. Inform. 2019, 95, 103208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Thielke, R.; Payne, J.; Gonzalez, N.; Conde, J.G. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J. Biomed. Inform. 2009, 42, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, S.S.; Thralls, K.J.; Kviatkovsky, S.A. Validity and reliability of a portable Balance Tracking System, BTrackS, in older adults. J. Geriatr. Phys. Ther. 2018, 41, 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Comprehensive R Archive Network. lme4: Linear Mixed-Effects Models Using ‘Eigen’ and S4. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/lme4/index.html (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Schielzeth, H.; Dingemanse, N.J.; Nakagawa, S.; Westneat, D.F.; Allegue, H.; Teplitsky, C.; Réale, D.; Dochtermann, N.A.; Garamszegi, L.Z.; Araya-Ajoy, Y.G. Robustness of linear mixed-effects models to violations of distributional assumptions. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2020, 11, 1141–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caronni, A.; Picardi, M.; Scarano, S.; Rota, V.; Guidali, G.; Bolognini, N.; Corbo, M. Minimal detectable change of gait and balance measures in older neurological patients: Estimating the standard error of the measurement from before-after rehabilitation data thanks to the linear mixed-effects models. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2024, 21, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, S.A.E.; Bots, M.L.; den Ruijter, H.M.; Palmer, M.K.; Grobbee, D.E.; Crouse, J.R.; O’Leary, D.H.; Evans, G.W.; Raichlen, J.S.; Moons, K.G.M.; et al. Multiple imputation of missing repeated outcome measurements did not add to linear mixed-effects models. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2012, 65, 686–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehdizadeh, H.; Khalaf, K.; Ghomashchi, H.; Taghizadeh, G.; Ebrahimi, I.; Sharabiani, P.T.A.; Sharabiani, P.T.A.; Mousavi, S.J.; Parnianpour, M. Effects of cognitive load on the amount and temporal structure of postural sway variability in stroke survivors. Exp. Brain Res. 2018, 236, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y.-R.; Chiu, W.-C.; Ting, C.-P.; Chiang, Y.-F.; Lin, T.-Y.; Chiang, H.-C.; Huang, C.-C.; Lu, C.-H. Postural sway serves as a predictive biomarker in balance and gait assessments for diabetic peripheral neuropathy screening: A community-based study. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2025, 22, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarabon, N.; Löfler, S.; Cvecka, J.; Sedliak, M.; Kern, H. Strength training in elderly people improves static balance: A randomized controlled trial. Eur. J. Transl. Myol. 2013, 23, 85–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iakovidis, P.; Nikolaos, M.; Stavros, K.; Savvas, M.; Apostolou, T.; Ilias, K.; Takidis, I. The effect of physiotherapeutic intervention on the static balance of elderly for secondary prevention of falls. Phys. Ther. Rehabil. J. 2017, 4, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Robitaille, Y.; Laforest, S.; Fournier, M.; Gauvin, L.; Parisien, M.; Corriveau, H.; Trickey, F.; Damestoy, N. Moving forward in fall prevention: An intervention to improve balance among older adults in real-world settings. Am. J. Public Health 2005, 95, 2049–2056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, Y.; Li, S.; Lv, X.; Wang, Y.; Xu, L.; Xi, Y.; Sun, Y.; Bao, J.; Liao, S.; Li, Y. Efficacy of sensory-based static balance training on the balance ability, aging attitude, and perceived stress of older adults in the community: A randomized controlled trial. BMC Geriatr. 2024, 24, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adcock, M.; Fankhauser, M.; Post, J.; Lutz, K.; Zizlsperger, L.; Luft, A.R.; Guimarães, V.; Schättin, A.; de Bruin, E.D. Effects of an in-home multicomponent exergame training on physical functions, cognition, and brain volume of older adults: A randomized controlled trial. Front. Med. 2020, 6, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motalebi, S.A.; Cheong, L.S.; Iranagh, J.A.; Mohammadi, F. Effect of low-cost resistance training on lower-limb strength and balance in institutionalized seniors. Exp. Aging Res. 2018, 44, 48–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubenstein, L.Z. Falls in older people: Epidemiology, risk factors and strategies for prevention. Age Ageing 2006, 35, ii37–ii41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orr, R. Contribution of muscle weakness to postural instability in the elderly. A systematic review. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2010, 46, 183–220. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Winter, D.A. Human balance and posture control during standing and walking. Gait Posture 1995, 3, 193–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrysomallis, C. Balance ability and athletic performance. Sports Med. 2011, 41, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillespie, L.D.; Robertson, M.C.; Gillespie, W.J.; Sherrington, C.; Gates, S.; Clemson, L.M.; Lamb, S.E. Interventions for preventing falls in older people living in the community. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2012, 2012, Cd007146. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lesinski, M.; Hortobágyi, T.; Muehlbauer, T.; Gollhofer, A.; Granacher, U. Effects of balance training on balance performance in healthy older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2015, 45, 1721–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Baseline | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | Category | Total (n = 373) | Intervention (n = 254) | Control (n = 119) | p |

| Age (years) | 74.3 ± 7.1 | 74.3 ± 6.9 | 74.3 ± 7.6 | 0.788 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 30.2 ± 6.2 | 29.7 ± 5.8 | 31.4 ± 6.9 | 0.022 1 | |

| Sex | Female | 327 | 225 | 102 | 0.538 |

| Male | 46 | 29 | 17 | ||

| Race/ethnicity | African American | 176 | 104 | 72 | 0.005 1 |

| Asian | 22 | 15 | 7 | ||

| Hispanic | 93 | 69 | 24 | ||

| White | 75 | 61 | 14 | ||

| Other | 7 | 5 | 2 | ||

| Self-reported health | Excellent | 22 | 13 | 9 | 0.651 |

| Very Good | 113 | 81 | 32 | ||

| Good | 172 | 117 | 55 | ||

| Fair | 57 | 36 | 21 | ||

| Poor | 9 | 7 | 2 | ||

| Financial status | Much more than adequate | 11 | 8 | 3 | 0.772 |

| More than adequate | 68 | 48 | 20 | ||

| Just enough | 217 | 149 | 68 | ||

| Less than adequate | 53 | 32 | 21 | ||

| Much less than adequate | 24 | 17 | 7 | ||

| Living status | Alone | 198 | 138 | 60 | 0.734 |

| Partner/ Spouse | 87 | 60 | 27 | ||

| Family/friend | 75 | 47 | 28 | ||

| Other | 13 | 9 | 4 | ||

| AP RMS (cm) | 0.84 ± 0.38 | 0.83 ± 0.37 | 0.86 ± 0.42 | 0.494 | |

| ML RMS (cm) | 0.32 ± 0.20 | 0.31 ± 0.21 | 0.33 ± 0.19 | 0.263 | |

| Sway speed variability (cm/s) | 1.56 ± 0.80 | 1.52 ± 0.75 | 1.66 ± 0.91 | 0.233 | |

| Sway area (cm2) | 2.19 ± 2.43 | 2.06 ± 2.13 | 2.50 ± 2.97 | 0.326 | |

| Variable | T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention | Control | Intervention | Control | Intervention | Control | Intervention | Control | |

| Participants with available data | 247 | 111 | 212 | 93 | 196 | 85 | 193 | 83 |

| AP RMS (cm) | 0.83 ± 0.37 | 0.86 ± 0.42 | 0.82 ± 0.36 | 0.89 ± 0.44 | 0.82 ± 0.33 | 0.88 ± 0.49 | 0.80 ± 0.34 | 0.79 ± 0.33 |

| ML RMS (cm) | 0.31 ± 0.21 | 0.33 ± 0.19 | 0.31 ± 0.23 | 0.35 ± 0.24 | 0.31 ± 0.21 | 0.35 ± 0.36 | 0.30 ± 0.18 | 0.27 ± 0.16 |

| Sway speed variability (cm/s) | 1.52 ± 0.75 | 1.66 ± 0.91 | 1.53 ± 0.76 | 1.68 ± 1.05 | 1.51 ± 0.66 | 1.73 ± 1.12 | 1.54 ± 0.72 | 1.41 ± 0.60 |

| Sway area (cm2) | 2.06 ± 2.13 | 2.50 ± 2.97 | 1.87 ± 1.95 | 2.86 ± 4.34 | 1.89 ± 1.70 | 3.53 ± 9.13 | 1.88 ± 1.56 | 1.78 ± 1.50 |

| Predictors | AP RMS (Log-Transformed) | ML RMS (Log-Transformed) | Sway Speed Variability (Log-Transformed) | Sway Area (Log-Transformed) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | 95% CI | p | Estimate | 95% CI | p | Estimate | 95% CI | p | Estimate | 95% CI | p | |

| (Intercept) | −1.17 | (−1.66, −0.67) | <0.001 1 | −2.71 | (−3.40, −2.03) | <0.001 1 | −0.91 | (−1.48, −0.34) | 0.002 1 | −2.07 | (−3.12, −1.02) | <0.001 1 |

| Group (intervention vs. control) | −0.02 | (−0.12, 0.08) | 0.667 | −0.03 | (−0.20, 0.14) | 0.729 | −0.04 | (−0.17, 0.09) | 0.531 | −0.07 | (−0.30, 0.15) | 0.522 |

| Time (T2) | 0.03 | (−0.05, 0.11) | 0.449 | 0.06 | (−0.05, 0.18) | 0.277 | 0.01 | (−0.08, 0.09) | 0.837 | 0.09 | (−0.03, 0.20) | 0.140 |

| Time (T3) | 0.00 | (−0.08, 0.08) | 0.975 | −0.06 | (−0.17, 0.06) | 0.355 | 0.02 | (−0.07, 0.10) | 0.727 | −0.01 | (−0.13, 0.11) | 0.833 |

| Time (T4) | −0.05 | (−0.14, 0.03) | 0.206 | −0.10 | (−0.22, 0.02) | 0.089 | −0.10 | (−0.19, −0.01) | 0.028 1 | −0.10 | (−0.21, 0.02) | 0.118 |

| Age | 0.01 | (0.00, 0.01) | 0.020 1 | 0.02 | (0.01, 0.02) | <0.001 1 | 0.01 | (0.00, 0.02) | 0.002 1 | 0.02 | (0.01, 0.04) | <0.001 1 |

| BMI | 0.01 | (0.00, 0.02) | <0.001 1 | 0.01 | (0.00, 0.02) | <0.006 1 | 0.01 | (0.01, 0.02) | <0.001 1 | 0.02 | (0.01, 0.03) | 0.001 1 |

| Sex (female vs. male) 2 | 0.08 | (−0.02, 0.19) | 0.126 | 0.06 | (−0.08, 0.21) | 0.398 | 0.13 | (0.01, 0.26) | 0.034 1 | 0.20 | (−0.02, 0.43) | 0.076 |

| Race/ethnicity (African American) 3 | 0.13 | (−0.13, 0.39) | 0.336 | −0.16 | (−0.52, 0.20) | 0.383 | 0.17 | (−0.13, 0.47) | 0.274 | −0.03 | (−0.58, 0.51) | 0.902 |

| Race/ethnicity (Asian) 3 | 0.26 | (−0.03, 0.55) | 0.085 | −0.02 | (−0.43, 0.38) | 0.910 | 0.36 | (0.02, 0.69) | 0.040 1 | 0.22 | (−0.40, 0.84) | 0.486 |

| Race/ethnicity (Hispanic) 3 | 0.10 | (−0.16, 0.36) | 0.450 | −0.16 | (−0.53, 0.21) | 0.388 | 0.13 | (−0.18, 0.43) | 0.405 | −0.09 | (−0.65, 0.47) | 0.754 |

| Race/ethnicity (White) 3 | 0.25 | (−0.02, 0.51) | 0.069 | −0.09 | (−0.46, 0.28) | 0.631 | 0.29 | (−0.01, 0.60) | 0.061 | 0.17 | (−0.39, 0.73) | 0.550 |

| Group * Time (T2) | −0.04 | (−0.14, 0.05) | 0.389 | −0.09 | (−0.23, 0.05) | 0.196 | −0.01 | (−0.11, 0.09) | 0.869 | −0.14 | (−0.28, 0.00) | 0.050 |

| Group * Time (T3) | −0.01 | (−0.10, 0.09) | 0.915 | 0.03 | (−0.11, 0.18) | 0.629 | 0.00 | (−0.11, 0.10) | 0.938 | −0.02 | (−0.16, 0.12) | 0.792 |

| Group * Time (T4) | 0.02 | (−0.08, 0.12) | 0.678 | 0.10 | (−0.04, 0.24) | 0.172 | 0.13 | (0.03, 0.24) | 0.014 1 | 0.08 | (−0.07, 0.22) | 0.293 |

| AP RMS (Log-Transformed) | ML RMS (Log-Transformed) | Sway Speed Variability (Log-Transformed) | Sway Area (Log-Transformed) | |||||||||

| Random effects | ||||||||||||

| Residual variance (σ2) | 0.08 | 0.16 | 0.09 | 0.16 | ||||||||

| Subject variance (τ00 studyID) | 0.08 | <0.001 1 | 0.15 | <0.001 1 | 0.11 | <0.001 1 | 0.44 | <0.001 1 | ||||

| Site variance (τ00 site) | 0.00 | 1.000 | 0.01 | 0.142 | 0.00 | 0.340 | 0.01 | 0.557 | ||||

| ICCsubjectID | 0.51 | 0.47 | 0.56 | 0.72 | ||||||||

| ICCsite | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.02 | ||||||||

| NstudyID | 373 | 373 | 373 | 373 | ||||||||

| Nsite | 17 | 17 | 17 | 17 | ||||||||

| Observations | 1220 | 1220 | 1220 | 1220 | ||||||||

| Marginal R2 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.09 | ||||||||

| Conditional R2 | 0.54 | 0.52 | 0.61 | 0.76 | ||||||||

| Predictors | AP RMS (Log-Transformed) | ML RMS (Log-Transformed) | Sway Speed Variability (Log-Transformed) | Sway Area (Log-Transformed) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Std β | 95% CI | p | Std β | 95% CI | p | Std β | 95% CI | p | Std β | 95% CI | p | |

| (Intercept) | 0.79 | (0.57, 1.01) | <0.001 1 | 0.78 | (0.54, 1.02) | <0.001 1 | 0.70 | (0.46, 0.94) | 0.002 1 | 0.43 | (0.21, 0.65) | <0.001 1 |

| Group (intervention vs. control) | −0.02 | (−0.10, 0.07) | 0.667 | −0.02 | (−0.13, 0.08) | 0.729 | −0.04 | (−0.14, 0.06) | 0.531 | −0.04 | (−0.13, 0.05) | 0.522 |

| Time (T2) | 0.03 | (−0.04, 0.10) | 0.449 | 0.05 | (−0.03, 0.12) | 0.277 | 0.00 | (−0.06, 0.07) | 0.837 | 0.04 | (−0.01, 0.09) | 0.140 |

| Time (T3) | 0.00 | (−0.07, 0.07) | 0.975 | −0.02 | (−0.10, 0.05) | 0.355 | 0.01 | (−0.05, 0.08) | 0.727 | 0.02 | (−0.03, 0.07) | 0.833 |

| Time (T4) | −0.05 | (−0.12, 0.02) | 0.206 | −0.07 | (−0.14, 0.01) | 0.089 | −0.08 | (−0.15, −0.01) | 0.028 1 | −0.04 | (−0.09, 0.01) | 0.118 |

| Age | 0.04 | (0.01, 0.07) | 0.020 1 | 0.07 | (0.04, 0.10) | <0.001 1 | 0.05 | (0.02, 0.08) | 0.002 1 | 0.07 | (0.04, 0.10) | <0.001 1 |

| BMI | 0.05 | (0.02, 0.09) | <0.001 1 | 0.04 | (0.01, 0.08) | <0.006 1 | 0.06 | (0.02, 0.09) | <0.001 1 | 0.05 | (0.01, 0.08) | 0.001 1 |

| Sex (female vs. male) 2 | 0.07 | (−0.02, 0.16) | 0.126 | 0.04 | (−0.05, 0.13) | 0.398 | 0.11 | (0.02, 0.21) | 0.034 1 | 0.09 | (0.00, 0.18) | 0.076 |

| Race/ethnicity (African American) 3 | 0.10 | (−0.12, 0.32) | 0.336 | −0.08 | (−0.31, 0.14) | 0.383 | 0.12 | (−0.11, 0.35) | 0.274 | −0.01 | (−0.23, 0.21) | 0.902 |

| Race/ethnicity (Asian) 3 | 0.21 | (−0.04, 0.45) | 0.085 | 0.00 | (−0.25, 0.26) | 0.910 | 0.27 | (0.01, 0.54) | 0.040 1 | 0.10 | (−0.15, 0.34) | 0.486 |

| Race/ethnicity (Hispanic) 3 | 0.08 | (−0.14, 0.30) | 0.450 | −0.08 | (−0.31, 0.15) | 0.388 | 0.09 | (−0.14, 0.33) | 0.405 | −0.04 | (−0.26, 0.18) | 0.754 |

| Race/ethnicity (White) 3 | 0.20 | (−0.02, 0.42) | 0.069 | −0.04 | (−0.27, 0.19) | 0.631 | 0.22 | (−0.02, 0.46) | 0.061 | 0.07 | (−0.15, 0.30) | 0.550 |

| Group * Time (T2) | −0.04 | (−0.12, 0.04) | 0.389 | −0.06 | (−0.15, 0.03) | 0.196 | 0.00 | (−0.08, 0.07) | 0.869 | −0.07 | (−0.13, −0.01) | 0.050 |

| Group * Time (T3) | 0.00 | (−0.09, 0.08) | 0.915 | 0.01 | (−0.08, 0.10) | 0.629 | 0.00 | (−0.09, 0.07) | 0.938 | −0.04 | (−0.11, 0.02) | 0.792 |

| Group * Time (T4) | 0.02 | (−0.06, 0.10) | 0.678 | 0.06 | (−0.03, 0.15) | 0.172 | 0.10 | (0.02, 0.18) | 0.014 1 | 0.02 | (−0.04, 0.09) | 0.293 |

| Group | Experienced at Least One Fall | Experienced One Fall | Experienced More Than One Fall | Experienced No Fall |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 21 | 16 | 5 | 98 |

| Intervention | 34 | 30 | 4 | 220 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Suarez, J.R.M.; Lafontant, K.; Banarjee, C.; Xie, R.; Park, J.-H.; Thiamwong, L. Effect of a Physio-Feedback Exercise Intervention Program on the Static Balance of Community-Dwelling Older Adults: A Clustered Randomized Controlled Trial. Geriatrics 2026, 11, 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics11010006

Suarez JRM, Lafontant K, Banarjee C, Xie R, Park J-H, Thiamwong L. Effect of a Physio-Feedback Exercise Intervention Program on the Static Balance of Community-Dwelling Older Adults: A Clustered Randomized Controlled Trial. Geriatrics. 2026; 11(1):6. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics11010006

Chicago/Turabian StyleSuarez, Jethro Raphael M., Kworweinski Lafontant, Chitra Banarjee, Rui Xie, Joon-Hyuk Park, and Ladda Thiamwong. 2026. "Effect of a Physio-Feedback Exercise Intervention Program on the Static Balance of Community-Dwelling Older Adults: A Clustered Randomized Controlled Trial" Geriatrics 11, no. 1: 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics11010006

APA StyleSuarez, J. R. M., Lafontant, K., Banarjee, C., Xie, R., Park, J.-H., & Thiamwong, L. (2026). Effect of a Physio-Feedback Exercise Intervention Program on the Static Balance of Community-Dwelling Older Adults: A Clustered Randomized Controlled Trial. Geriatrics, 11(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics11010006