Sarcopenia in Hospitalized Older Adults: A Cross-Sectional Study Comparing Diagnostic Thresholds and Handgrip Strength Measurement Tools

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

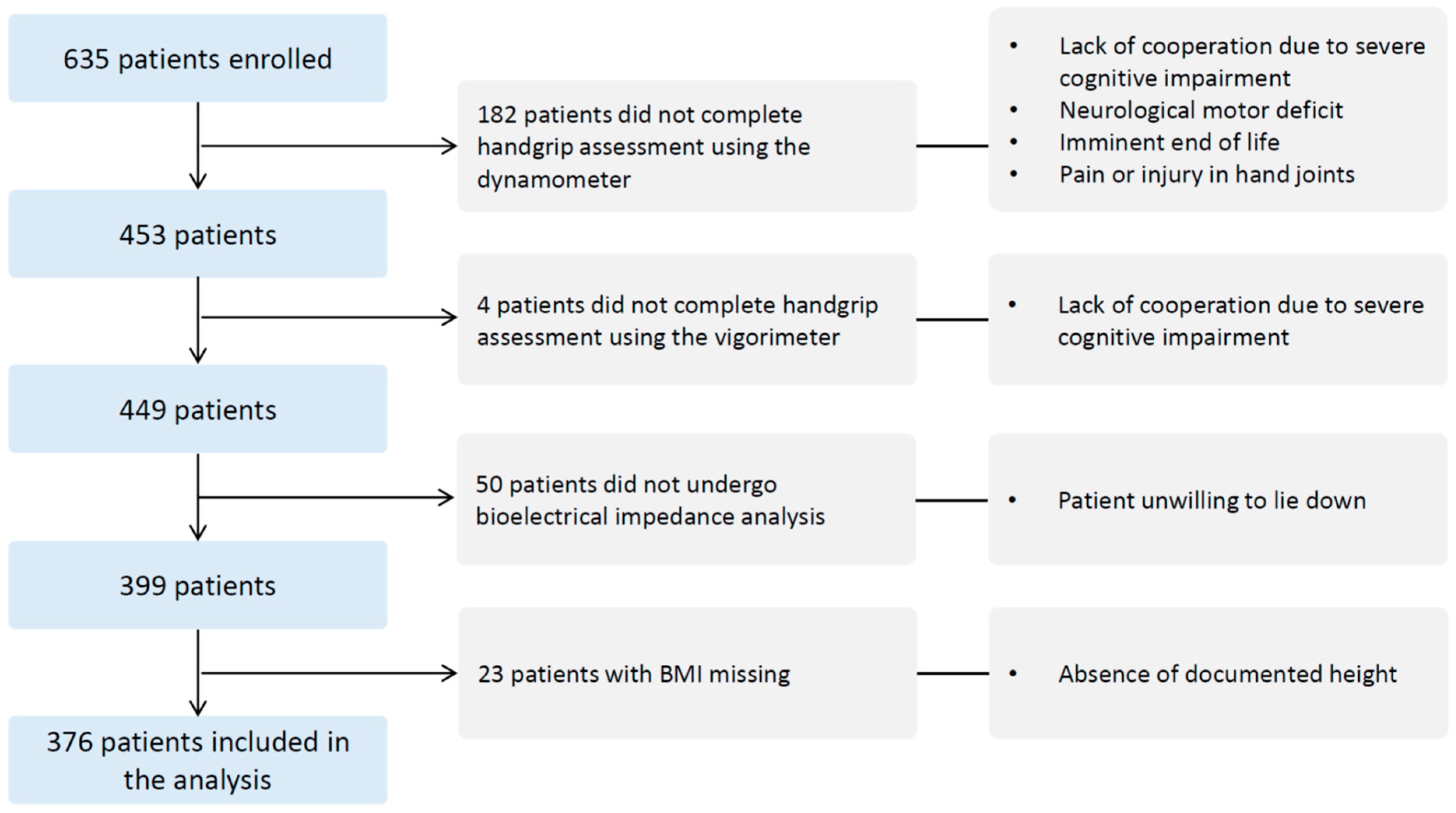

2.1. Design, Setting, and Population

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Handgrip Strength Assessment

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Population and Baseline Characteristic

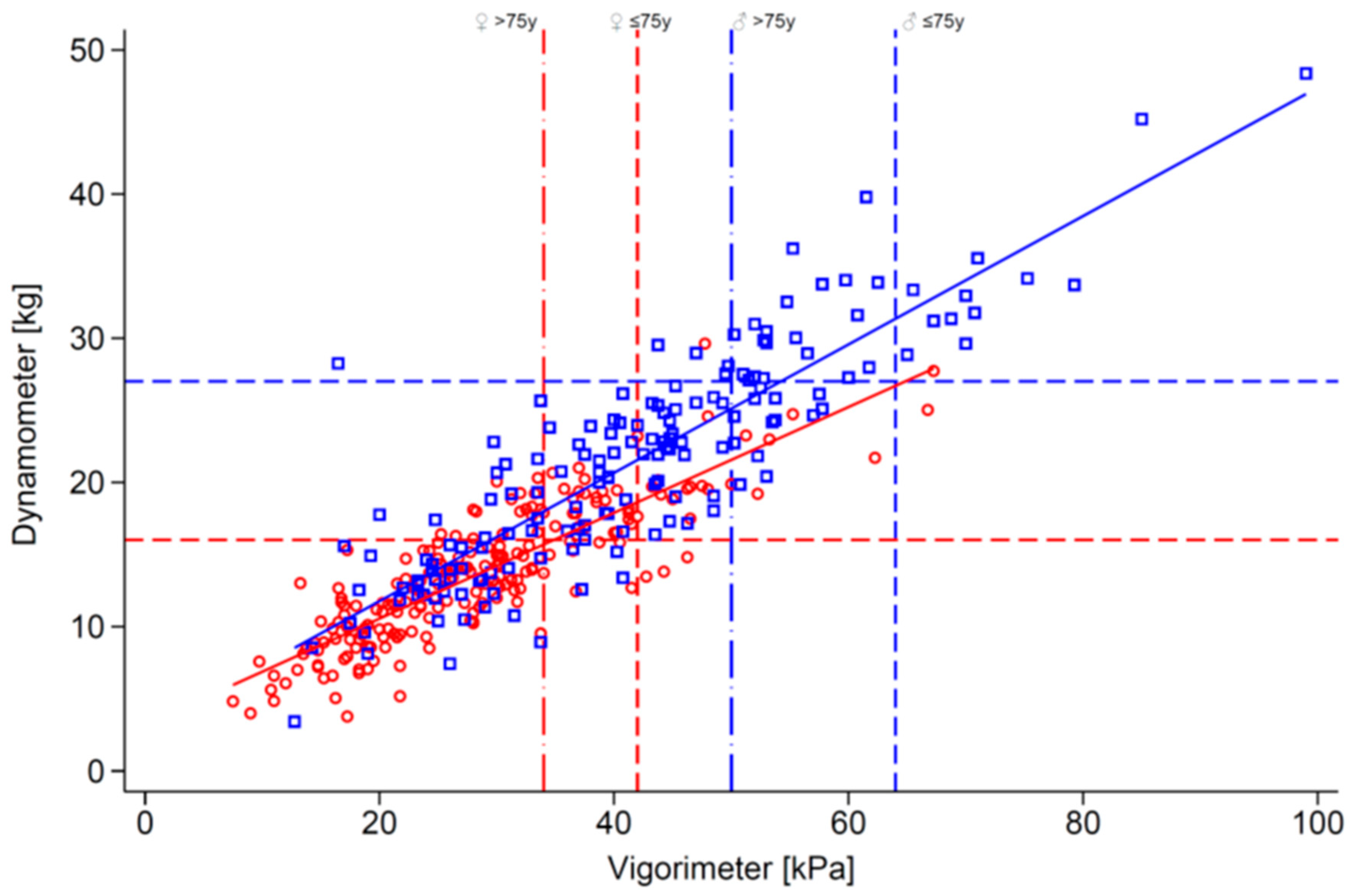

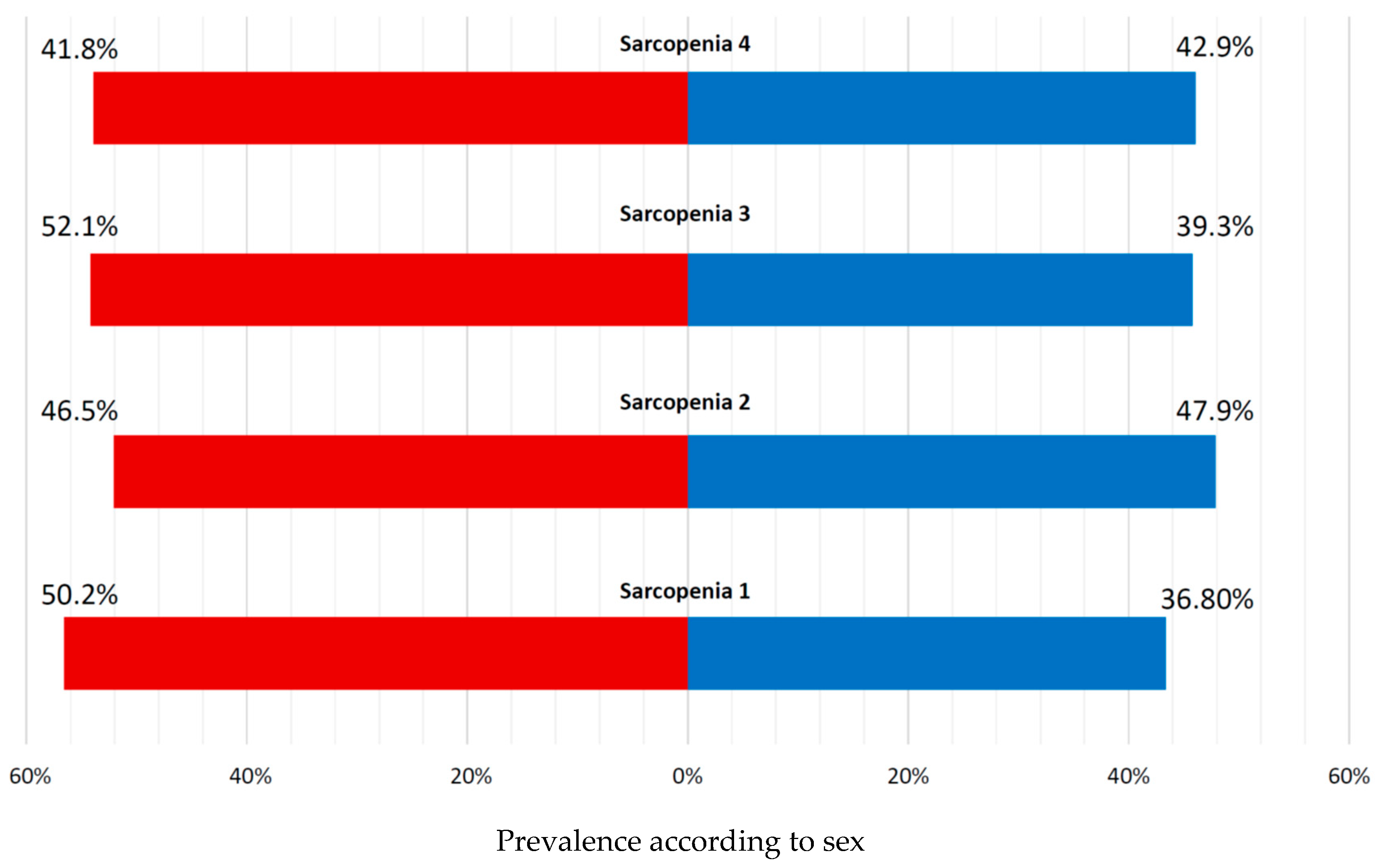

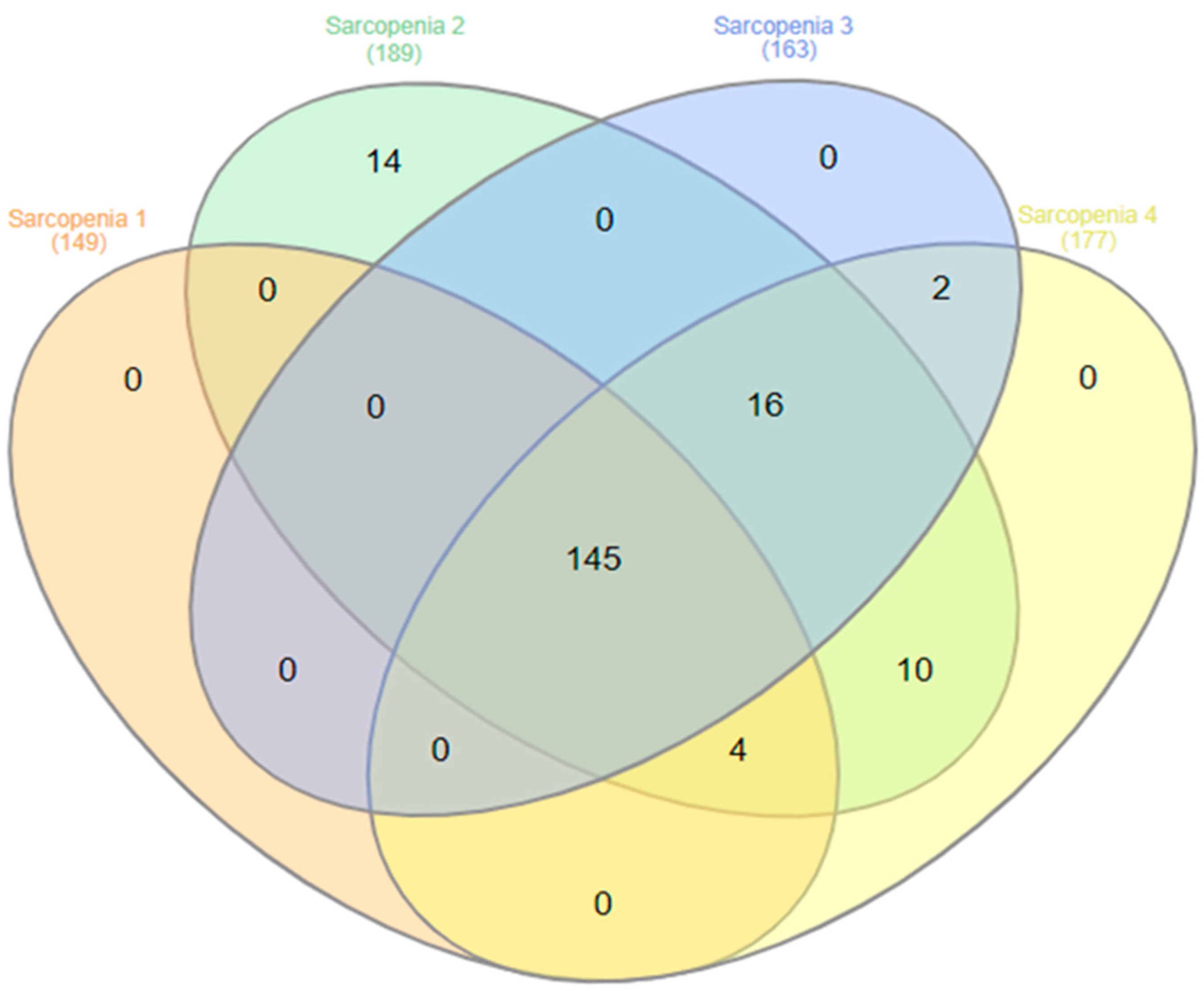

3.2. Muscle Strength Measures and Sarcopenia Prevalence According to Diagnostic Criteria

3.3. Clinical Correlates and Predictors of Sarcopenia

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bertschi, D.; Kiss, C.M.; Beerli, N.; Kressig, R.W. Sarcopenia in hospitalized geriatric patients: Insights into prevalence and associated parameters using new EWGSOP2 guidelines. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 75, 653–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachettini, N.P.; Bielemann, R.M.; Barbosa-Silva, T.G.; Menezes, A.M.B.; Tomasi, E.; Gonzalez, M.C. Sarcopenia as a mortality predictor in community-dwelling older adults: A comparison of the diagnostic criteria of the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 74, 573–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishikawa, T.; Taira, T.; Kakizawa, N.; Ohno, R.; Nagasaki, T. Negative impact of sarcopenia on survival in elderly patients with colorectal cancer receiving surgery: A propensity-score matched analysis. Oncol. Lett. 2024, 27, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, T.J.; Miksza, J.; Yates, T.; Lightfoot, C.J.; Baker, L.A.; Watson, E.L.; Zaccardi, F.; Smith, A.C. Association of sarcopenia with mortality and end-stage renal disease in those with chronic kidney disease: A UK Biobank study. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2021, 12, 586–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purnamasari, D.; Tetrasiwi, E.N.; Kartiko, G.J.; Astrella, C.; Husam, K.; Laksmi, P.W. Sarcopenia and Chronic Complications of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Rev. Diabet. Stud. 2022, 18, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepulveda-Loyola, W.; Osadnik, C.; Phu, S.; Morita, A.A.; Duque, G.; Probst, V.S. Diagnosis, prevalence, and clinical impact of sarcopenia in COPD: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2020, 11, 1164–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damluji, A.A.; Alfaraidhy, M.; AlHajri, N.; Rohant, N.N.; Kumar, M.; Al Malouf, C.; Bahrainy, S.; Ji Kwak, M.; Batchelor, W.B.; Forman, D.E.; et al. Sarcopenia and Cardiovascular Diseases. Circulation 2023, 147, 1534–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onoue, Y.; Izumiya, Y.; Hanatani, S.; Tanaka, T.; Yamamura, S.; Kimura, Y.; Araki, S.; Sakamoto, K.; Tsujita, K.; Yamamoto, E.; et al. A simple sarcopenia screening test predicts future adverse events in patients with heart failure. Int. J. Cardiol. 2016, 215, 301–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attaway, A.; Bellar, A.; Dieye, F.; Wajda, D.; Welch, N.; Dasarathy, S. Clinical impact of compound sarcopenia in hospitalized older adult patients with heart failure. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2021, 69, 1815–1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, S.L.; Quinlan, J.I.; Dhaliwal, A.; Armstrong, M.J.; Elsharkawy, A.M.; Greig, C.A.; Lord, J.M.; Lavery, G.G.; Breen, L. Sarcopenia in chronic liver disease: Mechanisms and countermeasures. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2021, 320, G241–G257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaudart, C.; Demonceau, C.; Reginster, J.Y.; Locquet, M.; Cesari, M.; Cruz Jentoft, A.J.; Bruyere, O. Sarcopenia and health-related quality of life: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2023, 14, 1228–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, A.S.; Guerra, R.S.; Fonseca, I.; Pichel, F.; Ferreira, S.; Amaral, T.F. Financial impact of sarcopenia on hospitalization costs. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 70, 1046–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, I.; Shepard, D.S.; Katzmarzyk, P.T.; Roubenoff, R. The healthcare costs of sarcopenia in the United States. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2004, 52, 80–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulou, S.K. Sarcopenia: A Contemporary Health Problem among Older Adult Populations. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Jentoft, A.J.; Bahat, G.; Bauer, J.; Boirie, Y.; Bruyere, O.; Cederholm, T.; Cooper, C.; Landi, F.; Rolland, Y.; Sayer, A.A.; et al. Sarcopenia: Revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age Ageing 2019, 48, 601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sipers, W.M.W.H.; de Blois, W.; Schols, J.M.G.A.; van Loon, L.J.C.; Verdijk, L.B. Sarcopenia Is Related to Mortality in the Acutely Hospitalized Geriatric Patient. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2019, 23, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Dobbeleer, L.; Theou, O.; Beyer, I.; Jones, G.R.; Jakobi, J.M.; Bautmans, I. Martin Vigorimeter assesses muscle fatigability in older adults better than the Jamar Dynamometer. Exp. Gerontol. 2018, 111, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sipers, W.M.; Verdijk, L.B.; Sipers, S.J.; Schols, J.M.; van Loon, L.J. The Martin Vigorimeter Represents a Reliable and More Practical Tool Than the Jamar Dynamometer to Assess Handgrip Strength in the Geriatric Patient. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2016, 17, 466.e1–466.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondrup, J.; Rasmussen, H.H.; Hamberg, O.; Stanga, Z. An ad hoc ESPEN Working Group. Nutritional risk screening (NRS 2002): A new method based on an analysis of controlled clinical trials. Clin. Nutr. 2003, 22, 321–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malmstrom, T.K.; Miller, D.K.; Simonsick, E.M.; Ferrucci, L.; Morley, J.E. SARC-F: A symptom score to predict persons with sarcopenia at risk for poor functional outcomes. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2016, 7, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagesch, M.; Wieczorek, M.; Abderhalden, L.A.; Lang, W.; Freystaetter, G.; Armbrecht, G.; Kressig, R.W.; Vellas, B.; Rizzoli, R.; Blauth, M.; et al. Grip strength cut-points from the Swiss DO-HEALTH population. Eur. Rev. Aging Phys. Act. 2023, 20, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graf, C.E.; Pichard, C.; Herrmann, F.R.; Sieber, C.C.; Zekry, D.; Genton, L. Prevalence of low muscle mass according to body mass index in older adults. Nutrition 2017, 34, 124–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cederholm, T.; Jensen, G.L.; Correia, M.I.T.D.; Gonzalez, M.C.; Fukushima, R.; Higashiguchi, T.; Baptista, G.; Barazzoni, R.; Blaauw, R.; Coats, A.J.S.; et al. GLIM criteria for the diagnosis of malnutrition—A consensus report from the global clinical nutrition community. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 10, 207–217. [Google Scholar]

- Buckinx, F.; Reginster, J.-Y.; Brunois, T.; Lenaerts, C.; Beaudart, C.; Croisier, J.-L.; Petermans, J.; Bruyère, O. Prevalence of sarcopenia in a population of nursing home residents according to their frailty status: Results of the SENIOR cohort. J. Musculoskelet. Neuronal Interact 2017, 17, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shafiee, G.; Keshtkar, A.; Soltani, A.; Ahadi, Z.; Larijani, B.; Heshmat, R. Prevalence of sarcopenia in the world: A systematic review and meta- analysis of general population studies. J. Diabetes Metab. Disord. 2017, 16, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ha, Y.-C.; Won, C.W.; Kim, M.; Chun, K.-J.; Yoo, J.-I. SARC-Fas a Useful Tool for Screening Sarcopenia in Elderly Patients with Hip Fractures. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2020, 24, 78–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayhew, A.J.; Amog, K.; Phillips, S.; Parise, G.; McNicholas, P.D.; de Souza, R.J.; Thabane, L.; Raina, P. The prevalence of sarcopenia in community-dwelling older adults, an exploration of differences between studies and within definitions: A systematic review and meta-analyses. Age Ageing 2019, 48, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, K.; Mullee, M.A.; Cox, N.; Russell, C.; Baxter, M.; Tilley, S.; Yao, G.L.; Zhu, S.; Roberts, H.C. The feasibility and acceptability of assessing and managing sarcopenia and frailty among older people with upper limb fracture. Age Ageing 2022, 51, afab252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodds, R.M.; Heslop, P.; Jaffar, J.; Davies, K.; Noble, J.M.; Shaw, F.E.; Witham, M.D.; Sayer, A.A. The assessment of sarcopenia and the frailty phenotype in the outpatient care of older people: Implementation and typical values obtained from the Newcastle SarcScreen project. Eur. Geriatr. Med. 2022, 13, 763–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, K.; Howson, F.F.A.; Culliford, D.J.; Sayer, A.A.; Roberts, H.C. The feasibility of assessing frailty and sarcopenia in hospitalised older people: A comparison of commonly used tools. BMC Geriatr. 2019, 19, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damanti, S.; Senini, E.; De Lorenzo, R.; Merolla, A.; Santoro, S.; Festorazzi, C.; Messina, M.; Vitali, G.; Sciorati, C.; Rovere-Querini, P. Acute Sarcopenia: Mechanisms and Management. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grima-Terrén, M.; Campanario, S.; Ramírez-Pardo, I.; Cisneros, A.; Hong, X.; Perdiguero, E.; Serrano, A.L.; Isern, J.; Muñoz-Cánoves, P. Muscle aging and sarcopenia: The pathology, etiology, and most promising therapeutic targets. Mol. Asp. Med. 2024, 100, 101319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tribolet, P.; Wunderle, C.; Kaegi-Braun, N.; Buchmueller, L.; Laager, R.; Stanga, Z.; Mueller, B.; Wagner, K.H.; Schuetz, P. Evaluating repeated handgrip strength measurements as predictors of mortality in malnourished hospitalized patients. Secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2025, 79, 897–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna Deschamps, E.; Herrmann, F.R.; De Macedo Ferreira, D.; Silva, M.; Graf, C.E.; Mendes, A. Two Methods of Handgrip Strength Assessment in Sarcopenia Evaluation: Associations with in-Hospital Mortality in Older Adults. Clin. Interv. Aging 2025, 20, 1619–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neumann, S.; Kwisda, S.; Krettek, C.; Gaulke, R. Comparison of the Grip Strength Using the Martin-Vigorimeter and the JAMAR-Dynamometer: Establishment of Normal Values. In Vivo 2017, 31, 917–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gränicher, P.; Maurer, Y.; Spörri, J.; Haller, B.; Swanenburg, J.; de Bie, R.A.; Lenssen, T.A.F.; Scherr, J. Accuracy and Reliability of Grip Strength Measurements: A Comparative Device Analysis. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2024, 9, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Male

Male  Female.

Female.

Male

Male  Female.

Female.

| Characteristics | Female | Male | Total | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 213 (56.6%) | 163 (43.4%) | 376 (100.0%) | |

| Age, y | 83.9 (10.8) | 81.1 (10.9) | 82.7 (10.9) | 0.0122 |

| Age category, n (%) | ||||

| <70 | 21 (9.9%) | 25 (15.3%) | 46 (12.2%) | 0.0763 |

| 70–79.9 | 40 (18.8%) | 38 (23.3%) | 78 (20.7%) | |

| 80–89.9 | 84 (39.4%) | 65 (39.9%) | 149 (39.6%) | |

| 90+ | 68 (31.9%) | 35 (21.5%) | 103 (27.4%) | |

| Level of care, n (%) | ||||

| Long-term | 31 (14.6%) | 31 (19.0%) | 62 (16.5%) | 0.4620 |

| Rehabilitation | 104 (48.8%) | 72 (44.2%) | 176 (46.8%) | |

| Acute | 78 (36.6%) | 60 (36.8%) | 138 (36.7%) | |

| Length of stay, day | 56.9 (79.9) | 72.7 (119.1) | 63.7 (98.9) | 0.1259 |

| Weight, kg | 60.2 (14.9) | 70.2 (12.3) | 64.6 (14.7) | <0.0010 |

| Height, cm | 158.4 (7.2) | 171.1 (6.8) | 163.9 (9.5) | <0.0010 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 24.0 (5.7) | 24.0 (3.8) | 24.0 (5.0) | 0.9340 |

| BMI category, n (%) | ||||

| <18.5 | 38 (17.8%) | 10 (6.1%) | 48 (12.8%) | <0.0010 |

| 18.5–24.9 | 92 (43.2%) | 88 (54.0%) | 180 (47.9%) | |

| 25–29.9 | 53 (24.9%) | 55 (33.7%) | 108 (28.7%) | |

| ≥30 | 30 (14.1%) | 10 (6.1%) | 40 (10.6%) | |

| NRS 0–7 (N = 229) | 3.7 (1.2) | 3.7 (1.2) | 3.7 (1.2) | 0.8880 |

| NRS ≥ 3, n (%) | 108 (81.8%) | 80 (82.5%) | 188 (82.1%) | 0.8982 |

| Fall during hospitalization | 85 (39.9%) | 85 (52.1%) | 170 (45.2%) | 0.0181 |

| SARC-F, n (%) N = 200 | ||||

| Normal | 28 (26.7%) | 34 (35.8%) | 62 (31.0%) | 0.1636 |

| Sarcopenia risk | 77 (73.3%) | 61 (64.2%) | 138 (69.0%) | |

| Jamar dynamometer, kg | 13.7 (4.6) | 21.4 (7.6) | 17.0 (7.2) | <0.0010 |

| Martin vigorimeter, kPa | 28.6 (10.8) | 41.7 (14.8) | 34.3 (14.2) | <0.0010 |

| FFMI, kg/m2 | 15.0 (2.8) | 17.2 (2.4) | 15.9 (2.8) | <0.0010 |

| FMI, kg/m2 | 9.0 (3.7) | 6.7 (2.5) | 8.0 (3.5) | <0.0010 |

| FFMI | Female | Male | Total | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Below | 122 (57.3%) | 79 (48.5%) | 201 (53.5%) | 0.090 |

| Normal | 91 (42.7%) | 84 (51.5%) | 175 (46.5%) | |

| Jamar dynamometer (EWGSOP2) | ||||

| Below | 140 (65.7%) | 116 (71.2%) | 256 (68.1%) | 0.262 |

| Normal | 73 (34.3%) | 47 (28.8%) | 120 (31.9%) | |

| Jamar dynamometer (SDOC) | ||||

| Below | 181 (85.0%) | 155 (95.1%) | 336 (89.4%) | 0.002 |

| Normal | 32 (15.0%) | 8 (4.9%) | 40 (10.6%) | |

| Martin vigorimeter (DO-HEALTH1) | ||||

| Below | 153 (71.8%) | 120 (73.6%) | 273 (72.6%) | 0.700 |

| Normal | 60 (28.2%) | 43 (26.4%) | 103 (27.4%) | |

| Martin vigorimeter (DO-HEALTH2) | ||||

| Below | 178 (83.6%) | 138 (84.7%) | 316 (84.0%) | 0.774 |

| Normal | 35 (16.4%) | 25 (15.3%) | 60 (16.0%) |

| Characteristics | Sarcopenia 1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | Total | p Value | |

| N | 227 (60.4%) | 149 (39.6%) | 376 (100.0%) | |

| Age, y | 80.4 ± 11.0 | 86.1 ± 9.8 | 82.7 ± 10.9 | <0.0010 |

| Age category, n (%) | ||||

| <70 | 37 (16.3%) | 9 (6.0%) | 46 (12.2%) | <0.0010 |

| 70–79.9 | 56 (24.7%) | 22 (14.8%) | 78 (20.7%) | |

| 80–89.9 | 91 (40.1%) | 58 (38.9%) | 149 (39.6%) | |

| 90+ | 43 (18.9%) | 60 (40.3%) | 103 (27.4%) | |

| Female sex, n (%) | 124 (54.6%) | 89 (59.7%) | 213 (56.6%) | 0.3285 |

| Level of care, n (%) | ||||

| Long-term | 32 (14.1%) | 30 (20.1%) | 62 (16.5%) | 0.1424 |

| Rehabilitation | 104 (45.8%) | 72 (48.3%) | 176 (46.8%) | |

| Acute | 91 (40.1%) | 47 (31.5%) | 138 (36.7%) | |

| Length of stay, day | 56.5 ± 84.4 | 74.6 ± 117.0 | 63.7 ± 98.9 | 0.0843 |

| Weight, kg | 70.8 ± 13.8 | 55.0 ± 10.4 | 64.6 ± 14.7 | <0.0010 |

| Height, cm | 164.7 ± 9.0 | 162.7 ± 10.0 | 163.9 ± 9.5 | 0.0491 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.1 ± 4.8 | 20.7 ± 2.9 | 24.0 ± 5.0 | <0.0010 |

| BMI category, n (%) | ||||

| <18.5 | 12 (5.3%) | 36 (24.2%) | 48 (12.8%) | <0.0010 |

| 18.5–24.9 | 77 (33.9%) | 103 (69.1%) | 180 (47.9%) | |

| 25–29.9 | 98 (43.2%) | 10 (6.7%) | 108 (28.7%) | |

| ≥30 | 40 (17.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 40 (10.6%) | |

| NRS 0–7 (N = 229) | 3.4 ± 1.2 | 4.2 ± 1.1 | 3.7 ± 1.2 | <0.0010 |

| NRS ≥ 3, n (%) | 104 (76.5%) | 84 (90.3%) | 188 (82.1%) | 0.0072 |

| Fall during hospitalization | 92 (40.5%) | 78 (52.3%) | 170 (45.2%) | 0.0243 |

| SARC-F, n (%) N = 200 | ||||

| Normal | 40 (34.2%) | 22 (26.5%) | 62 (31.0%) | 0.2471 |

| Sarcopenia risk | 77 (65.8%) | 61 (73.5%) | 138 (69.0%) | |

| Characteristics | Sarcopenia 1 | Sarcopenia 2 | Sarcopenia 3 | Sarcopenia 4 | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR Adj | 95% CI | p-Value | R2 | OR Adj | 95% CI | p-Value | R2 | OR Adj | 95% CI | p-Value | R2 | OR Adj | 95% CI | p-Value | R2 | |

| Male sex | 1.05 | (0.61–1.80) | 0.870 | 32% | 0.89 | (0.50–1.58) | 0.692 | 42% | 0.80 | (0.47–1.35) | 0.399 | 32% | 0.74 | (0.43–1.28) | 0.276 | 37% |

| Age | 1.07 | (1.04–1.10) | <0.001 | 1.04 | (1.01–1.06) | 0.012 | 1.04 | (1.01–1.06) | 0.006 | 1.03 | (1.00–1.06) | 0.030 | ||||

| BMI | 0.68 | (0.63–0.74) | <0.001 | 0.59 | (0.52–0.65) | <0.001 | 0.67 | (0.62–0.73) | <0.001 | 0.64 | (0.58–0.70) | <0.001 | ||||

| In-hospital fall during | 1.39 | (0.81–2.36) | 0.229 | 1.62 | (0.90–2.91) | 0.107 | 1.48 | (0.87–2.52) | 0.144 | 1.63 | (0.94–2.84) | 0.083 | ||||

| Level of care | ||||||||||||||||

| Acute | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||

| Long-term | 2.70 | (1.23–5.96) | 0.014 | 1.86 | (0.81–4.29) | 0.144 | 1.95 | (0.90–4.22) | 0.088 | 2.28 | (1.03–5.05) | 0.043 | ||||

| Rehabilitation | 1.70 | (0.94–3.09) | 0.078 | 1.42 | (0.75–2.69) | 0.284 | 1.46 | (0.81–2.61) | 0.207 | 1.72 | (0.93–3.15) | 0.082 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Hanna-Deschamps, E.; Herrmann, F.R.; Chirouzes, D.; Claudepierre Buratti, L.; Luthy, C.; Frangos, E.; Pautex, S.; Genton, L.; Zekry, D.; Graf, C.E.; et al. Sarcopenia in Hospitalized Older Adults: A Cross-Sectional Study Comparing Diagnostic Thresholds and Handgrip Strength Measurement Tools. Geriatrics 2026, 11, 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics11010007

Hanna-Deschamps E, Herrmann FR, Chirouzes D, Claudepierre Buratti L, Luthy C, Frangos E, Pautex S, Genton L, Zekry D, Graf CE, et al. Sarcopenia in Hospitalized Older Adults: A Cross-Sectional Study Comparing Diagnostic Thresholds and Handgrip Strength Measurement Tools. Geriatrics. 2026; 11(1):7. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics11010007

Chicago/Turabian StyleHanna-Deschamps, Eliana, François R. Herrmann, Diana Chirouzes, Laurence Claudepierre Buratti, Christophe Luthy, Emilia Frangos, Sophie Pautex, Laurence Genton, Dina Zekry, Christophe E. Graf, and et al. 2026. "Sarcopenia in Hospitalized Older Adults: A Cross-Sectional Study Comparing Diagnostic Thresholds and Handgrip Strength Measurement Tools" Geriatrics 11, no. 1: 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics11010007

APA StyleHanna-Deschamps, E., Herrmann, F. R., Chirouzes, D., Claudepierre Buratti, L., Luthy, C., Frangos, E., Pautex, S., Genton, L., Zekry, D., Graf, C. E., & Mendes, A. (2026). Sarcopenia in Hospitalized Older Adults: A Cross-Sectional Study Comparing Diagnostic Thresholds and Handgrip Strength Measurement Tools. Geriatrics, 11(1), 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics11010007