A Multidimensional Perspective on Resilience in Later Life: A Systematic Literature Review of Protective Factors and Adaptive Processes in Ageing

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Research Methods

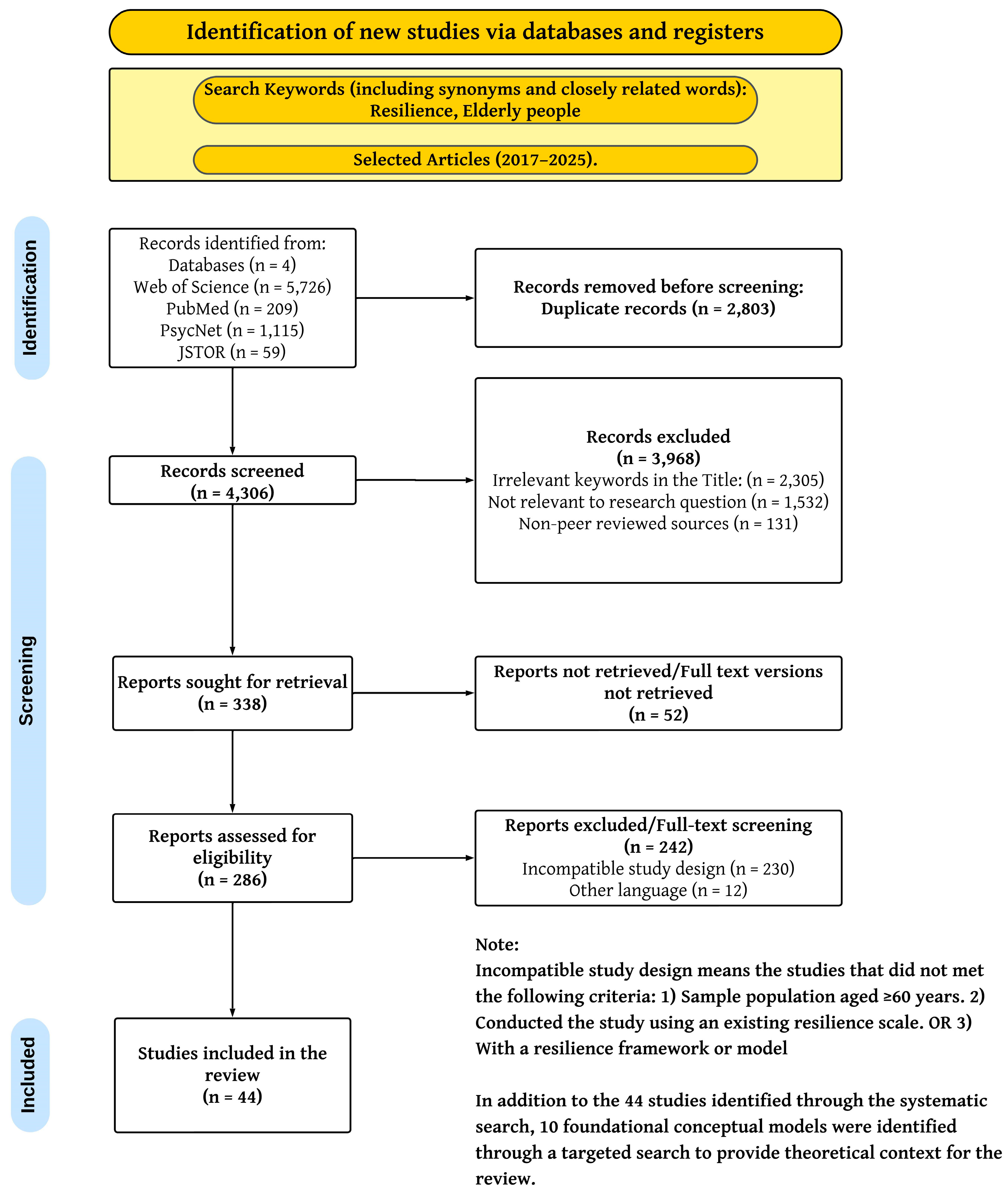

2.1. Literature Search

2.2. Screening and Inclusion Criteria

3. Results

3.1. Included Studies

3.2. Characteristics of Studies on Key Resilience Factors

3.3. Synthesis of Key Resilience Factors

3.3.1. Protective Factors

3.3.2. Risk Factors

3.4. Risk of Bias of Included Studies

| Study | Population Characteristics | Resilience Measurement Method | Key Protective Factors | Key Risk Factors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taylor A.M. et al., 2019 [49] | sample size = 655, age ~ 73–79, mean age = 76 | BRS | Cognitive ability, physical fitness, and wellbeing | - |

| Akkila S. et al., 2023 [71] | sample size = 79, age = 70–88, mean age = 75 | EORTCQLQ-C30 | Functional ability | - |

| Choi J.Y., 2024 [61] | Sample size = 57, age ≥ 65 | ACTH stimulation test, orthostatic blood pressure measurement, dual-task gait tests | Personal competence (Self-efficacy, purposefulness) | - |

| Costenoble A. et al., 2022 [36] | Sample size = 405, age = 80–97, mean age = 83 | CD-RISC | Activities of Daily Living (ADLs) | - |

| Costenoble A. et al., 2023 [37] | Sample size = 322, mean age 83.04 | CD-RISC | ADLs, social participation, and psychological resilience | - |

| Drazich B.F. et al., 2025 [72] | Sample size = 314, mean age = 82.74 | Physical Resilience Scale | Physical resilience | - |

| Gijzel S.M.W. et al., 2017 [67] | Sample size = 22, age ≥ 70, mean age = 84.0 | Self-Rated Health Monitoring | Physical, Mental, and Social Health | - |

| Gijzel S.M.W. et al., 2020 [64] | Sample size = 121, mean age = 84.3 | Dynamic Resilience Indicator | Health and life satisfaction. | Anxiety |

| Hao M. et al., 2024 [68] | Sample size = 1754, age = 70–84 | Physiological System Network model | Age, Gender, education, cognition, Functional status, physical, mental, and social health | Disease history |

| Hu F.W. et al., 2021 [69] | Sample size = 192, age = 65–97, mean age = 76.29 | PRIFOR | Gender, marital status, education, health, mental health, ADLs, quality of life | Depression, frailty |

| Hu F.W. et al., 2024 [73] | Sample size = 413, age ≥ 65, mean age = 76.34 | PRIFOR) | Physical and mental health | - |

| Jyväkorpi S.K. et al., 2018 [59] | Sample size = 394, age = 82–97, mean age = 88 | Finnish version of Resilience scale | Good nutrition, physical activity, and psychological health | - |

| Kim E. et al., 2024 [50] | Sample size = 1826, age = 70–84, mean age = 77.6 | BRS | - | Stress |

| Kolk D. et al., 2022 [74] | Sample size = 207, ag ≥ 70, mean age = 79.8 | Single Baseline Measurements scales | Pre-illness Functioning, Cognitive function | - |

| Lenti M.V. et al., 2022 [46] | Sample size = 143, median age = 69 | CD-RISC | Functional ability, cognitive ability, and education | - |

| Miller M.J. et al., 2024 [62] | Sample size = 3778, mean age = 75.4 | Modified Poisson regression analyses | Perceived control over one’s health | Depression |

| Kim S. et al., 2024 [75] | Sample size = 1397, age = 72–90, mean age = 82.2 | Parallel-serial mediation model using PROCESS macro | Cognitive function | Depression and stress |

| Olson K. et al., 2021 [51] | Sample size = 3199, mean age = 72.2 | BRS | Social support, physical activity | Depression |

| Rebagliati G.A. et al., 2017 [60] | Sample size = 81, age = 60–94 | RS | Functional status | Depression |

| Rodrigues F. and Tavares D., 2024 [48] | Sample size = 201, age ≥ 60 | CD-RISC- 25BRASIL | ADLs, self-perceived health | History and depression |

| Rolandi E. et al., 2024 [76] | Sample size = 404, age = 83–87 | Multidimensional Assessment | Executive functions (skills like planning, problem-solving, and mental flexibility), lifestyle | Depression and anxiety |

| Stenroth S.M. et al., 2023 [77] | Sample size = 681, age = 71–84 | Hardy-Gill resilience scale | - | Frailty |

| Sugawara I. et al., 2022 [54] | Sample size = 1064, age = 74–86 | RS-14 | Social engagement | - |

| Taylor M.G. and Carr D., 2021 [55] | Sample size = 11,050 to 12,823 | SRS | Mastery (control over one’s life) and high self-esteem | - |

| Yang Y. and Wen M., 2017 [24] | Sample size = 11,112, age = 65–84, mean age = 82.9 | Resilience Scale | Age | Disability |

| Ye B. et al., 2024 [38] | Sample size = 4033, mean age = 71.0 | CD-RISC | - | Frailty |

| Wang Y. et al., 2024 [47] | Sample size= 280, age= 60–95, mean age= 74.21 | CD-RISC | Social support | - |

| Jiang G.-q. et al., 2024 [70] | Sample size = 2495, age ≥ 60 | SRQS | Marital status, monthly income, sleep quality, ADLs, and physical exercise | Smoking, depression, and hypertension |

| Wister A.V. et al., 2021 [39] | Sample size = 13,064, age ≥ 65, mean age = 73.75 | CD-RISC | Social support, life satisfaction | - |

| Zafari M. et al., 2023 [40] | Sample size = 384, age ≥ 60, mean age = 67.41 | CD-RISC | Spiritual wellbeing | Depression |

| Angevaare M.J. et al., 2020 [17] | Sample size = 246, age ≥ 60 | interRAI-LTCF | Cognitive function, family support, social engagement, health, mental health | - |

| Remm S.E. et al., 2023 [53] | Sample size = 143, age ≥ 65, mean age= 79 | BRS | Self-efficacy, mobility difficulties, and physical activity | Depression |

| Kim J.R. et al., 2023 [41] | Sample size = 284, age ≥ 60, mean age= 68 | CD-RISC | Social participation | - |

| Li Y.T. et al., 2022 [65] | Sample size = 226, age ≥ 60 | RSOA | Life satisfaction | - |

| Silva R.C.M. et al., 2022 [42] | Sample size = 65, mean age ≥ 65, men age = 71.32 | CD-RISC | Happiness | - |

| Kunuroglu F. et al., 2021 [66] | Sample size = 264, age = 60–96, mean age = 70.29 | ARM | Physical and Psychological health, satisfaction, and engagement with life, self-compassion | - |

| Asch R.H. et al., 2021 [63] | Sample size = 3001, age = 60–99, mean age = 73.2 | PRAPDI | Secure attachment style, mindfulness, and purpose in life | - |

| Bartholomaeus J.D. et al., 2019 [52] | Sample size = 110, mean age = 70.69 | BRS | Social participation | - |

| Lau S. et al., 2018 [56] | Sample size = 1506, age = 65–74, mean age = 69.5 | RS | Health | - |

| Morete M.C. et al., 2018 [43] | Sample size = 108, mean age = 79.9 | CD-RISC | Health, spiritual wellbeing | - |

| Kondabi F. et al., 2017 [44] | Sample size = 500, age = 60–69, mean age = 64.5 | CD-RISC | Self-esteem, marital status, income, age | - |

| Phillips S.P. et al., 2017 [57] | Sample size = 1724, age = 65–74, mean age = 69.5 | RS | Social engagement | - |

| Laird K.T. et al., 2019 [45] | Sample size = 337, age = 60–89, mean age = 70.45 | CD-RISC | Quality of Life, Mental Health, Vitality, Apathy, Social functioning, Emotional Wellbeing, General Health, Age | Depression, Anxiety |

| Resnick B. et al., 2019 [58] | Sample = 172, age = 65–96, mean age = 81.09 | RS | Genetics and Social Interaction | - |

3.5. Resilience Models

4. Discussion

4.1. Methodological Considerations in Resilience Measurement

4.2. Macro-Environmental Level Factors

4.3. Meso-Social Level Factors

4.4. Micro-Individual Level Factors

4.5. Bio-Physiological Level Factors

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| CD-RISC | Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale |

| BRS | Brief Resilience Scale |

| RS | Wagnild Resilience Scale |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| RNA | Ribonucleic acid |

| PRIFOR | Physical Resilience Instrument for Older Adults |

| SRS | Simplified Resilience Score |

| SRQS | Stress Resilience Quotient Scale |

| RSOA | Resilience scale for older adults |

| ARM | Adult Resilience Measure |

| PRAPDI | Psychological Resilience Against Physical Difficulties Index |

| EORTCQLQ-C30 | European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire |

Appendix A

References

- World Health Organization. World Report on Ageing and Health. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/186463 (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- Nations, U. Ageing. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/global-issues/ageing (accessed on 29 April 2025).

- World Population Prospects 2022: Summary of Results. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/sites/www.un.org.development.desa.pd/files/undesa_pd_2022_wpp_key-messages.pdf (accessed on 29 April 2025).

- UNFPA. Ageing. Available online: https://www.unfpa.org/ageing (accessed on 29 April 2025).

- Lv, Y.; Fan, L.; Zhou, J.; Ding, E.; Shen, J.; Tang, S.; He, Y.; Shi, X. Burden of non-communicable diseases due to population ageing in China: Challenges to healthcare delivery and long term care services. BMJ 2024, 387, e076529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pathak, N. Ageing in India and ASEAN: The relevance of social protection preparedness. The ASEAN Magazine, 8 July 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Solanki, G.; Kelly, G.; Cornell, J.; Daviaud, E.; Geffen, L. Population ageing in South Africa: Trends, impact, and challenges for the health sector. South. Afr. Health Rev. 2019, 2019, 175–182. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Ageing and Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health (accessed on 29 April 2025).

- Rowe, J.W.; Kahn, R.L. Successful aging. Gerontologist 1997, 37, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagnild, G. Resilience and successful aging. Comparison among low and high income older adults. J. Gerontol. Nurs. 2003, 29, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baltes, P.B.; Smith, J. New frontiers in the future of aging: From successful aging of the young old to the dilemmas of the fourth age. Gerontology 2003, 49, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behr, L.C.; Simm, A.; Kluttig, A.; Grosskopf Großkopf, A. 60 years of healthy aging: On definitions, biomarkers, scores and challenges. Ageing Res. Rev. 2023, 88, 101934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonfoh, B.; Koné, B.V.; Koffi, Y.D.; Miyama, T.; Fujimoto, Y.; Fokou, G.; Zinsstag, J.; Sugimura, R.; Makita, K. Healthy Aging: Comparative Analysis of Local Perception and Diet in Two Health Districts of Côte d’Ivoire and Japan. Front. Aging 2022, 3, 817371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Association, A.P. The Road to Resilience. Available online: https://www.apa.org/helpcenter/road-resilience (accessed on 29 April 2025).

- Trică, A.; Golu, F.; Sava, N.I.; Licu, M.; Zanfirescu, Ș.A.; Adam, R.; David, I. Resilience and successful aging: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Psychol. 2024, 248, 104357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byun, J.; Jung, D. The influence of daily stress and resilience on successful ageing. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2016, 63, 482–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angevaare, M.J.; Roberts, J.; van Hout, H.P.J.; Joling, K.J.; Smalbrugge, M.; Schoonmade, L.J.; Windle, G.; Hertogh, C.M.P.M. Resilience in older persons: A systematic review of the conceptual literature. Ageing Res. Rev. 2020, 63, 101144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resnick, B. Resilience in Older Adults. Top. Geriatr. Rehabil. 2014, 30, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, K.M.; Reyes-Rodriguez, M.F.; Altamar, P.; Soulsby, L.K. Resilience amongst Older Colombians Living in Poverty: An Ecological Approach. J. Cross Cult. Gerontol. 2016, 31, 385–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Netuveli, G.; Wiggins, R.D.; Montgomery, S.M.; Hildon, Z.; Blane, D. Mental health and resilience at older ages: Bouncing back after adversity in the British Household Panel Survey. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2008, 62, 987–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Ma, S.; Chen, L.; Yang, L. Resilience measurement and analysis of intercity public transportation network. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2024, 131, 104202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tóth, G.; Kucséber, L.; Pollák, Z.; Jáki, E. Financial resilience and adaptation: Analyzing the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on businesses rated successful. Soc. Econ. 2024, 46, 342–367. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, W.J.; Chen, L.K.; Peng, L.N.; Chiou, S.T.; Chou, P. Personal mastery attenuates the adverse effect of frailty on declines in physical function of older people: A 6-year population-based cohort study. Medicine 2016, 95, e4661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Wen, M. Psychological Resilience and the Onset of Activity of Daily Living Disability Among Older Adults in China: A Nationwide Longitudinal Analysis. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2015, 70, 470–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosco, T.D.; Howse, K.; Brayne, C. Healthy ageing, resilience and wellbeing. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2017, 26, 579–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitson, H.E.; Duan-Porter, W.; Schmader, K.E.; Morey, M.C.; Cohen, H.J.; Colón-Emeric, C.S. Physical Resilience in Older Adults: Systematic Review and Development of an Emerging Construct. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2016, 71, 489–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Sun, C.; Zhang, X. Analyzing and forecasting China’s financial resilience: Measurement techniques and identification of key influencing factors. J. Financ. Stab. 2025, 76, 101372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLeod, S.; Musich, S.; Hawkins, K.; Alsgaard, K.; Wicker, E.R. The impact of resilience among older adults. Geriatr. Nurs. 2016, 37, 266–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Kessel, G. The ability of older people to overcome adversity: A review of the resilience concept. Geriatr. Nurs. 2013, 34, 122–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosco, T.D.; Kok, A.; Wister, A.; Howse, K. Conceptualising and operationalising resilience in older adults. Health Psychol. Behav. Med. 2019, 7, 90–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szanton, S.; Gill, J.; Thorpe, J.R. The Society-to-Cells Model of Resilience in Older Adults. Annu. Rev. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2010, 30, 5–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, T.H.; Habibi, N.; Aromataris, E.; Stone, J.C.; Leonardi-Bee, J.; Sears, K.; Hasanoff, S.; Klugar, M.; Tufanaru, C.; Moola, S.; et al. The revised JBI critical appraisal tool for the assessment of risk of bias for quasi-experimental studies. JBI Evid. Synth. 2024, 22, 378–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connor, K.M.; Davidson, J.R. Development of a new resilience scale: The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Depress. Anxiety 2003, 18, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.W.; Dalen, J.; Wiggins, K.; Tooley, E.; Christopher, P.; Bernard, J. The brief resilience scale: Assessing the ability to bounce back. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2008, 15, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagnild, G.M.; Young, H.M. Development and psychometric evaluation of the Resilience Scale. J. Nurs. Meas. 1993, 1, 165–178. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Costenoble, A.; Rossi, G.; Knoop, V.; Debain, A.; Smeys, C.; Bautmans, I.; Verté, D.; De Vriendt, P.; Gorus, E. Does psychological resilience mediate the relation between daily functioning and prefrailty status? Int. Psychogeriatr. 2022, 34, 253–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costenoble, A.; Knoop, V.; Debain, A.; Bautmans, I.; Van Laere, S.; Lieten, S.; Rossi, G.; Verté, D.; Gorus, E.; De Vriendt, P.; et al. Transitions in robust and prefrail octogenarians after 1 year: The influence of activities of daily living, social participation, and psychological resilience on the frailty state. BMC Geriatr. 2023, 23, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, B.; Li, Y.; Bao, Z.; Gao, J. Psychological Resilience and Frailty Progression in Older Adults. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2447605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrew, V.; Wister, T.D.C. (Eds.) Introduction: Perspectives of Resilience and Aging. In Resilience and Aging, 1st ed.; Risk, Systems and Decisions; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Zafari, M.; Sadeghipour Roudsari, M.; Yarmohammadi, S.; Jahangirimehr, A.; Marashi, T. Investigating the relationship between spiritual well-being, resilience, and depression: A cross-sectional study of the elderly. Psychogeriatrics 2023, 23, 442–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Kim, J.R.; Lee, C. Association of resilience with successful ageing and the mediating role of community participation. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2023, 19, e074099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, R.C.M.; Zambaldi, C.F.; Costa, S.P.G.A.; Urquiza, P.A.C.; Machado, L.; Cantilino, A. Are physicians aging well? Subjective successful aging, happiness, optimism, and resilience in a sample of Brazilian aging doctors. Eur. J. Psychiatry 2022, 36, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morete, M.C.; Solano, J.P.C.; Boff, M.S.; Filho, W.J.; Ashmawi, H.A. Resilience, depression, and quality of life in elderly individuals with chronic pain followed up in an outpatient clinic in the city of São Paulo, Brazil. J. Pain Res. 2018, 11, 2561–2566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izadi-Avanji, F.S.; Kondabi, F.; Afazel, M.; Akbari, H.; Zerati, M. Measurement and Predictors of Resilience Among Community-Dwelling Elderly in Kashan, Iran: A Cross-Sectional Study. Nurs. Midwifery Stud. 2016, 6, e36397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laird, K.T.; Lavretsky, H.; Paholpak, P.; Vlasova, R.M.; Roman, M.; St Cyr, N.; Siddarth, P. Clinical correlates of resilience factors in geriatric depression. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2019, 31, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenti, M.V.; Brera, A.S.; Ballesio, A.; Croce, G.; Padovini, L.; Bertolino, G.; Di Sabatino, A.; Klersy, C.; Corazza, G.R. Resilience is associated with frailty and older age in hospitalised patients. BMC Geriatr. 2022, 22, 569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, G.; Ding, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, C.; Sun, M. Correlation Between Resilience and Social Support in Elderly Ischemic Stroke Patients. World Neurosurg. 2024, 184, e518–e523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, F.; Tavares, D. Resilience and mortality in older adults: Structural equation analysis. Texto Contexto. Enfermagem. 2024, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, A.M.; Ritchie, S.J.; Madden, C.; Deary, I.J. Associations between Brief Resilience Scale scores and ageing-related domains in the Lothian Birth Cohort 1936. Psychol. Aging 2020, 35, 329–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.; Lee, Y.; Kim, M.; Kim, S.; Shin, Y.; Han, J. Perceived stress as a mediator of the association between psychological resilience and functional declines. Innov. Aging 2024, 8, 856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, K.; Howard, M.; McCaffery, J.; Dutton, G.; Espeland, M.; Johnson, K.; Simpson, F.; Wing, R. Resilience among older adults with Type 2 Diabetes from the Look AHEAD trial. Innov. Aging 2021, 5, 903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartholomaeus, J.D.; Van Agteren, J.E.M.; Iasiello, M.P.; Jarden, A.; Kelly, D. Positive Aging: The Impact of a Community Wellbeing and Resilience Program. Clin. Gerontol. 2019, 42, 377–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remm, S.; Halcomb, E.; Peters, K.; Hatcher, D.; Frost, S. Self-efficacy, resilience and healthy ageing among older people who have an acute hospital admission: A cross-sectional study. Nurs. Open 2023, 10, 7168–7177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugawara, I.; Takayama, M.; Ishioka, Y. The protective effect of resilience on shrinkage of friendship in later life. Innov. Aging 2022, 6, 649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, M.G.; Carr, D. Psychological Resilience and Health Among Older Adults: A Comparison of Personal Resources. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2021, 76, 1241–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lau, S.; Fernandes, J.; Phillips, S. Impact of resilience on health in older adults: A cross-sectional analysis from the International Mobility in Aging Study (IMIAS). BMJ Open 2018, 8, e023779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, S.P.; Auais, M.; Belanger, E.; Alvarado, B.; Zunzunegui, M.V. Life-course social and economic circumstances, gender, and resilience in older adults: The longitudinal International Mobility in Aging Study (IMIAS). SSM Popul. Health 2016, 2, 708–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resnick, B.; Klinedinst, N.J.; Yerges-Armstrong, L.; Magaziner, J.; Orwig, D.; Hochberg, M.C.; Gruber-Baldini, A.L.; Dorsey, S.G. Genotype, resilience and function and physical activity post hip fracture. Int. J. Orthop. Trauma Nurs. 2019, 34, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jyväkorpi, S.K.; Urtamo, A.; Pitkälä, K.H.; Strandberg, T.E. Nutrition, Daily Walking and Resilience Are Associated with Physical Function in the Oldest Old Men. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2018, 22, 1176–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rebagliati, G.A.; Sciumè, L.; Iannello, P.; Mottini, A.; Antonietti, A.; Caserta, V.A.; Gattoronchieri, V.; Panella, L.; Callegari, C. Frailty and resilience in an older population. The role of resilience during rehabilitation after orthopedic surgery in geriatric patients with multiple comorbidities. Funct. Neurol. 2016, 31, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, J.Y.; Kim, K.I. Resilience components, postoperative complications, and quality of life deterioration after pancreatectomy. Innov. Aging 2024, 8, 1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.J.; Cenzer, I.; Covinsky, K.E.; Finlayson, E.; Raue, P.J.; Tang, V.L. Associations of Resilience, Perceived Control of Health, and Depression with Geriatric Outcomes after Surgery. Ann. Surg. 2024, 10–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asch, R.H.; Esterlis, I.; Southwick, S.M.; Pietrzak, R.H. Pietrzak. Risk and resilience factors associated with traumatic loss-related PTSD in U. S. military veterans: Results from the National Health and Resilience in Veterans Study. Psychiatry Res. 2021, 298, 113775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gijzel, S.M.W.; Rector, J.; van Meulen, F.B.; van der Loeff, R.S.; van de Leemput, I.A.; Scheffer, M.; Olde Rikkert, M.G.M.; Melis, R.J.F. Measurement of Dynamical Resilience Indicators Improves the Prediction of Recovery Following Hospitalization in Older Adults. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2020, 21, 525–530.e524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.T.; Ow, Y.S.Y. Development of resilience scale for older adults. Aging Ment. Health 2022, 26, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunuroglu, F.; Yuzbasi, D.V. Factors promoting successful aging in Turkish older adults: Self compassion, psychological resilience, and attitudes towards aging. J. Happiness Stud. Interdiscip. Forum Subj. Well Being 2021, 22, 3663–3678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gijzel, S.M.W.; van de Leemput, I.A.; Scheffer, M.; Roppolo, M.; Olde Rikkert, M.G.M.; Melis, R.J.F. Dynamical Resilience Indicators in Time Series of Self-Rated Health Correspond to Frailty Levels in Older Adults. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2017, 72, 991–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, M.; Zhang, H.; Li, Y.; Hu, X.; Hu, Z.; Jiang, X.; Wang, J.; Sun, X.; Liu, Z.; Davis, D.; et al. Using Physiological System Networks to Elaborate Resilience Across Frailty States. J. Gerontol. Ser. A 2024, 79, glad243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, F.W.; Lin, C.H.; Lai, P.H.; Lin, C.Y. Predictive Validity of the Physical Resilience Instrument for Older Adults (PRIFOR). J. Nutr. Health Aging 2021, 25, 1042–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, G.-q.; He, Y.-K.; Li, T.-F.; Qin, Q.-R.; Wang, D.-N.; Huang, F.; Sun, Y.-H.; Li, J. Association of psychological resilience and cognitive function in older adults: Based on the Ma’ anshan Healthy Aging Cohort Study. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2024, 116, 105166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akkila, S.; Mahal, S.; Dawdy, K.; Cao, X.; Szumacher, E. Functional decline and resilience in older adults over the age of 70 receiving radiotherapy for breast cancer: A pilot study. J. Geriatr. Oncol. 2023, 14, 101476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drazich, B.F.; Gurlu, M.; Kuzmik, A.; Galik, E.; Wells, C.L.; Boltz, M.; Resnick, B. The association of physical resilience and post-discharge adverse events among older adults with dementia. Aging Ment. Health 2025, 29, 973–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, F.W.; Yueh, F.R.; Fang, T.J.; Chang, C.M.; Lin, C.Y. Testing a Conceptual Model of Physiologic Reserve, Intrinsic Capacity, and Physical Resilience in Hospitalized Older Patients: A Structural Equation Modelling. Gerontology 2024, 70, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolk, D.; Melis, R.J.F.; MacNeil-Vroomen, J.L.; Buurman, B.M. Physical Resilience in Daily Functioning Among Acutely Ill Hospitalized Older Adults: The Hospital-ADL Study. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2022, 23, 903.e1–903.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Won, C.W.; Kim, S.; Park, J.H.; Kim, M.; Kim, B.; Ryu, J. The Effect of Psychological Resilience on Cognitive Decline in Community-Dwelling Older Adults: The Korean Frailty and Aging Cohort Study. Korean J. Fam. Med. 2024, 45, 331–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolandi, E.; Rossi, M.; Colombo, M.; Pettinato, L.; Del Signore, F.; Aglieri, V.; Bottini, G.; Guaita, A. Lifestyle, Cognitive, and Psychological Factors Associated with a Resilience Phenotype in Aging: A Multidimensional Approach on a Population-Based Sample of Oldest-Old (80+). J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2024, 79, gbae132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenroth, S.M.; Pynnönen, K.; Haapanen, M.J.; Vuoskoski, P.; Mikkola, T.M.; Eriksson, J.G.; von Bonsdorff, M.B. Association between resilience and frailty in older age: Findings from the Helsinki Birth Cohort Study. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2023, 115, 105119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldwin, C.; Igarashi, H. Chapter 6 An Ecological Model of Resilience in Late Life. Annu. Rev. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2012, 32, 115–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windle, G.; Bennett, K.M. Caring relationships: How to promote resilience in challenging times. In The Social Ecology of Resilience: A Handbook of Theory and Practice; Springer Science + Business Media: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 219–231. [Google Scholar]

- Wister, A.; Klasa, K.; Linkov, I. A Unified Model of Resilience and Aging: Applications to COVID-19. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 865459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wister, A.V.; Coatta, K.L.; Schuurman, N.; Lear, S.A.; Rosin, M.; MacKey, D. A Lifecourse Model of Multimorbidity Resilience: Theoretical and Research Developments. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 2016, 82, 290–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.J.W.; Reed, M.; Girard, T.A. Advancing resilience: An integrative, multi-system model of resilience. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2017, 111, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klasa, K.; Galaitsi, S.; Wister, A.; Linkov, I. System models for resilience in gerontology: Application to the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Geriatr. 2021, 21, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lima, G.S.; Figueira, A.L.G.; Carvalho, E.C.; Kusumota, L.; Caldeira, S. Resilience in Older People: A Concept Analysis. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cárdenas, A.; López, L. Analysis Matrix of Resilience in the Face of Disability, Old Age and Poverty. Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. 2010, 57, 175–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, F. Strengthening Family Resilience; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus, S.; Folkman, S. Stress and Cognitive Processes; Springer Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Polk, L.V. Toward a middle-range theory of resilience. Adv. Nurs. Sci. 1997, 19, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, D.; Sarkar, M. Psychological resilience: A review and critique of definitions, concepts, and theory. Eur. Psychol. 2013, 18, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windle, G. What is resilience? A review and concept analysis. Rev. Clin. Gerontol. 2011, 21, 152–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, A.D.; Bergeman, C.S.; Boker, S.M. Resilience comes of age: Defining features in later adulthood. J. Personal. 2009, 77, 1777–1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seeman, T.E.; McEwen, B.S. Impact of social environment characteristics on neuroendocrine regulation. Psychosom. Med. 1996, 58, 459–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elder, G.H., Jr. The life course as developmental theory. Child Dev. 1998, 69, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hildon, Z.; Smith, G.; Netuveli, G.; Blane, D. Understanding adversity and resilience at older ages. Sociol. Health Illn. 2008, 30, 726–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George, L.K. Still Happy After All These Years: Research Frontiers on Subjective Well-being in Later Life. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 2010, 65B, 331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungar, M. Resilience across Cultures. Br. J. Soc. Work. 2008, 38, 218–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonucci, T.C.; Akiyama, H.; Takahashi, K. Attachment and close relationships across the life span. Attach. Hum. Dev. 2004, 6, 353–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungar, M. The social ecology of resilience: Addressing contextual and cultural ambiguity of a nascent construct. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2011, 81, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiles, J.L.; Wild, K.; Kerse, N.; Allen, R.E.S. Resilience from the point of view of older people: ‘There’s still life beyond a funny knee’. Soc. Sci. Med. 2012, 74, 416–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, F.; Sancheti, H.; Patil, I.; Cadenas, E. Energy metabolism and inflammation in brain aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2016, 100, 108–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillespie, B.M.; Chaboyer, W.; Wallis, M.; Grimbeek, P. Resilience in the operating room: Developing and testing of a resilience model. J. Adv. Nurs. 2007, 59, 427–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol. Rev. 1977, 84, 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, S.; Teixeira, L.; Esteves, R.; Ribeiro, F.; Pereira, F.; Teixeira, A.; Magalhães, C. Spirituality and quality of life in older adults: A path analysis model. BMC Geriatr. 2020, 20, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, S.; Singh, K.N.; Thomas, A.; Troise, C.; Bresciani, S. Does financial inclusion build the financial resilience of elderly women? Ventur. Cap. 2024, 27, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steptoe, A.; Zaninotto, P. Lower socioeconomic status and the acceleration of aging: An outcome-wide analysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 14911–14917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smeeth, D.; Beck, S.; Karam, E.G.; Pluess, M. The role of epigenetics in psychological resilience. Lancet Psychiatry 2021, 8, 620–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.; Guan, T.; Shafiq, K.; Yu, Q.; Jiao, X.; Na, D.; Li, M.; Zhang, G.; Kong, J. Mitochondrial dysfunction in aging. Ageing Res. Rev. 2023, 88, 101955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srivastava, S. The Mitochondrial Basis of Aging and Age-Related Disorders. Genes 2017, 8, 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Militello, R.; Luti, S.; Gamberi, T.; Pellegrino, A.; Modesti, A.; Modesti, P.A. Physical Activity and Oxidative Stress in Aging. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iakovou, E.; Kourti, M. A Comprehensive Overview of the Complex Role of Oxidative Stress in Aging, The Contributing Environmental Stressors and Emerging Antioxidant Therapeutic Interventions. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2022, 14, 827900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seong, H.; Lashley, H.; Bowers, K.; Holmes, S.; Fortinsky, R.H.; Zhu, S.; Corazzini, K.N. Resilience in relation to older adults with multimorbidity: A scoping review. Geriatr. Nurs. 2022, 48, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Criteria Domain | Inclusion Details | Exclusion Details |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Studies focused on adults aged 60 and above, or with a mean sample age of 60 or older. | Studies focused exclusively on younger or middle-aged adult populations. |

| Concept/Content | For empirical studies: Must investigate protective/risk factors associated with resilience AND quantitatively measure resilience using a validated or explicitly defined scale. For theoretical papers: Must primarily explore or present a conceptual model of resilience relevant to aging. | Studies where resilience was mentioned only in passing, without being a primary focus of the research. |

| Publication Type | Peer-reviewed journal articles (quantitative, qualitative, or mixed-methods). Book chapters or review articles presenting foundational conceptual models. | Dissertations, conference abstracts, editorials, book reviews, and other non-peer-reviewed “grey literature.” |

| Publication Date | For empirical studies on factors: Published between January 2017 and October 2025. For foundational conceptual models: No date restriction. | For empirical studies on factors: Published before 2017. |

| Language | Full-text article published in English. | Articles published in languages other than English. |

| Accessibility | Full text retrievable through university library subscriptions or inter-library loan. | Full text not accessible. |

| Model & Author(s) (Year) | Core Concept/Definition | Key Components/Levels | Key Contribution to Understanding Resilience in Aging |

|---|---|---|---|

| An Ecological Model of Resilience (Aldwin et al., 2012 [78]) | Resilience is an ecological process that depends on the interplay of resources across multiple levels. |

| Frames resilience as being dependent on a multilevel inventory of available resources. |

| The Society-to-cells Model of Resilience (Szanton et al., 2010 [31]) | Resilience is a dynamic, multilevel process with continuous, bidirectional influences from the macro-societal level down to the micro-cellular level. |

| Provides a comprehensive, integrated framework that links social determinants of health to biological outcomes. |

| An Ecological Model of Resilience (Bennett et al., 2016; Windle & Bennett, 2012 [19,79]) | Resilience is shaped by the interaction of resources across three core ecological domains. |

| Provides a focused, three-tiered ecological framework commonly used in European gerontology research. |

| A Unified Model of Resilience and Aging (UMRA) (Wister et al., 2018 [80]) | Resilience is an integrated, life-course process in which individual and socio-ecological resources are mobilized to navigate adversity, leading to different recovery trajectories. |

| Provides a system-level model that connects individual psychological processes with disaster response functions and a life course perspective. |

| A Life Course Model of Multimorbidity Resilience (Wister et al., 2016 [81]) | Resilience is a dynamic process of positive adaptation to the disruptions caused by multiple chronic illnesses, shaped by resources accumulated throughout the life course. |

| Specifically frames resilience within the critical geriatric context of multimorbidity and an individual’s life course. |

| An Integrative, Multi-System Model of Resilience (MSMR) (Liu et al., 2017 [82]) | Resilience is a multi-system construct composed of three interacting layers: a stable biological core, acquired interpersonal skills, and the external socio-ecological context. |

| Provides a tiered framework that distinguishes between stable, “trait-like” biological foundations and more malleable psychological and social factors. Advocates for including physiological markers. |

| System Models for Resilience in Gerontology (Klasa et al., 2021 [83]) | Adapts systems engineering and disaster resilience frameworks to aging, conceptualizing resilience as a quantifiable property of an older adult nested within a multilevel socio-ecological system. |

| Applies a complex systems perspective from disaster science to aging, with a strong focus on quantifying resilience to inform policy and interventions more effectively. |

| Resilience Model (Santos Lima et al., 2023 [84]) | Resilience is a process whereby an individual leverages available resources to produce positive, adaptive behaviors. |

| Presents resilience as a clear input-output process, distinguishing between the resources one has and the adaptive actions one takes. |

| Resilience Matrix (Cárdenas et al., 2010 [85]) | Based on Bronfenbrenner’s theory, resilience emerges from the interaction of various processes throughout an individual’s life. |

| Provides a process-centric view, emphasizing how diverse types of interactions contribute to resilience, rather than merely listing static factors [86,87,88,89]. |

| Feature | Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) | Brief Resilience Scale (BRS) | Wagnild & Young Resilience Scale (RS) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Concept Measured | A person’s capacity to cope with and bounce back from adversity. | A person’s ability to recover from stress. | The internal strengths and positive traits that enable positive adaptation. |

| Theoretical Basis | Trait-based: Measures enduring personal characteristics. | Outcome-based: Measures the process of “bouncing back.” | Trait-based: Measures existential strengths. |

| Typical Target Population | Universally used in both community and clinical populations, including PTSD and anxiety research. | Designed for the general population; ideal for tracking changes in recovery ability over time. | Originally developed with older women, focuses on positive adaptation and is widely used in aging research. |

| Key Components | Personal competence, control, secure relationships, and spiritual influence. | Directly measures the ability to recover from adversity. | Purpose, perseverance, equanimity, self-reliance, existential aloneness |

| Key Strength | Very well-validated, with multiple versions (25, 10, and 2-item) for different settings. | Short, easy to administer, and directly measures the concept of “bouncing back.” | Focuses on positive, existential strengths, such as purpose and perseverance, rather than stress recovery. |

| Limitation | The 25-item version may be too lengthy for some clinical settings. | Does not measure the underlying traits that contribute to resilience. | Can be less sensitive to changes after short-term interventions compared to the BRS. |

| Original Reliability (Cronbach’s α) | Excellent (α = 0.89) | Excellent (α = 0.80–0.91) | Excellent (α = 0.91) |

| Evidence of Validity | Strong: Demonstrated good convergent validity (correlated positively with hardiness, social support; correlated negatively with perceived stress, disability) and good discriminant validity (not correlated with sexual functioning). | Good: Supported by a clear one-factor structure. Demonstrated strong convergent validity (correlated positively with optimism, purpose, social support, active coping; correlated negatively with pessimism, alexithymia, negative coping styles, stress, anxiety, depression, physical symptoms). Test–retest reliability was acceptable. | Strong: Demonstrated good concurrent validity (correlated positively with life satisfaction, morale, self-reported health; correlated negatively with depression). |

| Original Validation Paper | Connor & Davidson (2003) [33] | Smith et al. (2008) [34] | Wagnild & Young (1993) [35] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jacob, B.A.; Walker, C.; O’Sullivan, M.; Rouse, P.; Parsons, M. A Multidimensional Perspective on Resilience in Later Life: A Systematic Literature Review of Protective Factors and Adaptive Processes in Ageing. Geriatrics 2025, 10, 154. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics10060154

Jacob BA, Walker C, O’Sullivan M, Rouse P, Parsons M. A Multidimensional Perspective on Resilience in Later Life: A Systematic Literature Review of Protective Factors and Adaptive Processes in Ageing. Geriatrics. 2025; 10(6):154. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics10060154

Chicago/Turabian StyleJacob, Benjamin A., Cameron Walker, Michael O’Sullivan, Paul Rouse, and Matthew Parsons. 2025. "A Multidimensional Perspective on Resilience in Later Life: A Systematic Literature Review of Protective Factors and Adaptive Processes in Ageing" Geriatrics 10, no. 6: 154. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics10060154

APA StyleJacob, B. A., Walker, C., O’Sullivan, M., Rouse, P., & Parsons, M. (2025). A Multidimensional Perspective on Resilience in Later Life: A Systematic Literature Review of Protective Factors and Adaptive Processes in Ageing. Geriatrics, 10(6), 154. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics10060154