Exploring Frailty Status and Blood Biomarkers: A Multidimensional Approach to Alzheimer’s Diagnosis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Biological Samples Collection

2.4. Neuropsychological Assessment

2.5. Frailty Assessment

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Cohort Description

3.2. Associations Between Plasma Biomarkers, Frailty, and Clinical Variables

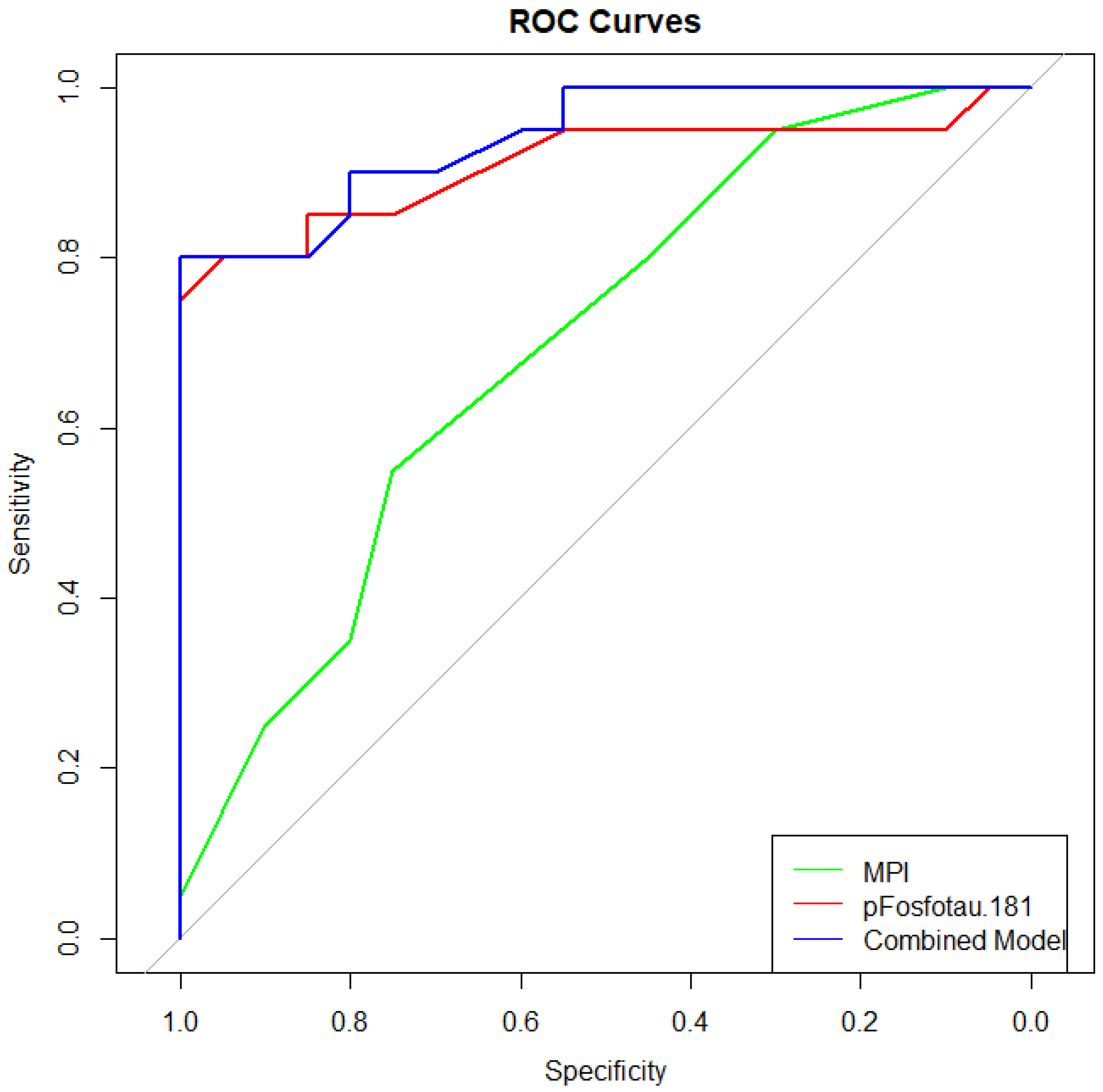

3.3. Diagnostic Performance

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AD | Alzheimer’s Disease |

| MPI | Multidimensional Prognostic Index |

| Aβ42 | Amyloid Beta 1–42 |

| Aβ40 | Amyloid Beta 1–40 |

| p-tau181 | Phosphorylated Tau 181 |

| tTau | Total Tau |

| NfL | Neurofilament light |

| CSF | Cerebrospinal Fluid |

| MMSE | Mini-Mental State Examination |

| MoCA | Montreal Cognitive Assessment |

| FAB | Frontal Assessment Battery |

| CDT | Clock Drawing Test |

| SPMSQ | Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire |

| ESS | Exton Smith Scale |

| MNA | Mini Nutritional Assessment |

| CIRS | Cumulative Illness Rating Scale |

| ADL | Activities of Daily Living |

| IADL | Instrumental Activities of Daily Living |

| FTD | Frontotemporal Dementia |

| DLB | Dementia with Lewy Bodies |

| VD | Vascular Dementia |

| ROC | Receiver Operating Characteristic |

| AUC | Area Under the Curve |

| CLEIA | Chemiluminescent Enzyme Immunoassay |

| APOE | Apolipoprotein E |

| PET | Positron Emission Tomography |

References

- Corral-Pérez, J.; Casals, C.; Ávila-Cabeza-de-Vaca, L.; González-Mariscal, A.; Martínez-Zaragoza, I.; Villa-Estrada, F.; Reina-Campos, R.; Vázquez-Sánchez, M.Á. Health factors associated with cognitive frailty in older adults living in the community. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2023, 15, 1232460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clegg, A.; Bates, C.; Young, J.; Ryan, R.; Nichols, L.; Teale, E.A.; Mohammed, M.A.; Parry, J.; Marshall, T. Development and validation of an electronic frailty index using routine primary care electronic health record data. Age Ageing 2016, 45, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fried, L.P.; Tangen, C.M.; Walston, J.; Newman, A.B.; Hirsch, C.; Gottdiener, J.; Seeman, T.; Tracy, R.; Kop, W.J.; Burke, G.; et al. Frailty in older adults: Evidence for a phenotype. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2001, 56, M146–M156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Li, Q.; Wang, S.; Huang, C.; Xue, Q.-L.; Szanton, S.L.; Liu, M. Sustained Frailty Remission and Dementia Risk in Older Adults: A Longitudinal Study. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2024, 20, 6268–6277. [Google Scholar]

- Franceschi, C.; Campisi, J. Chronic inflammation (inflammaging) and its potential contribution to age-associated diseases. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2014, 69 (Suppl. 1), S4–S9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soysal, P.; Stubbs, B.; Lucato, P.; Luchini, C.; Solmi, M.; Peluso, R.; Sergi, G.; Isik, A.T.; Manzato, E.; Maggi, S.; et al. Inflammation and frailty in the elderly: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res. Rev. 2016, 31, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Li, Y.; Hu, N.; Gong, L.; Zhao, Q.; Guo, Q. Association of Frailty with Plasma Phosphorylated Tau in Community-Dwelling Older Adults. BMC Geriatr. 2022, 22, 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, L.M.K.; Theou, O.; Pena, F.; Rockwood, K. Frailty Trajectories in Three Cohorts of Community-Dwelling Older Adults: A Ten-Year Follow-Up Study. Aging Med. 2021, 4, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kocagoncu, E.; Nesbitt, D.; Emery, T.; Hughes, L.E.; Henson, R.N.; Rowe, J.B.; Cambridge Centre for Ageing and Neuroscience. Neurophysiological and brain structural markers of cognitive frailty differ from Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurosci. 2022, 42, 1362–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutiérrez-Zúñiga, R.; Davis, J.R.C.; Ruddy, K.; De Looze, C.; Carey, D.; Meaney, J.; Kenny, R.A.; Knight, S.P.; Romero-Ortuno, R. Structural brain signatures of frailty, defined as accumulation of self-reported health deficits in older adults. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2023, 15, 1065191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canevelli, M.; Jackson-Tarlton, C.; Rockwood, K. Frailty for neurologists: Perspectives on how frailty influences care planning. Lancet Neurol. 2024, 23, 1147–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheltens, P.; De Strooper, B.; Kivipelto, M.; Holstege, H.; Chételat, G.; Teunissen, C.E.; Cummings, J.; Van Der Flier, W.M. Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet 2021, 397, 1577–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jack, C.R.; Bennett, D.A., Jr.; Blennow, K.; Carrillo, M.C.; Dunn, B.; Haeberlein, S.B.; Holtzman, D.M.; Jagust, W.; Jessen, F.; Karlawish, J.; et al. NIA-AA Research Framework: Toward a biological definition of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Demen. 2018, 14, 535–562. [Google Scholar]

- Jack, C.R.; Jr Andrews, J.S.; Beach, T.G.; Buracchio, T.; Dunn, B.; Graf, A.; Hansson, O.; Ho, C.; Jagust, W.; McDade, E.; et al. Revised criteria for diagnosis and staging of Alzheimer’s disease: Alzheimer’s Association Workgroup. Alzheimers Demen. 2024, 20, 5143–5169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisoni, G.B.; Festari, C.; Massa, F.; Cotta Ramusino, M.; Orini, S.; Aarsland, D.; Agosta, F.; Babiloni, C.; Borroni, B.; Cappa, S.F.; et al. European intersocietal recommendations for the biomarker-based diagnosis of neurocognitive disorders. Lancet Neurol. 2024, 23, 302–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauchet, O.; Matskiv, J.; Gaudreau, P.; Allali, G.; Vaillant-Ciszewicz, A.-J.; Guerin, O.; Grose, A. Frailty, Cognitive Impairment, and Incident Major Neurocognitive Disorders: Results of the NuAge Cohort Study. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2023, 94, 1079–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ward, D.D.; Ranson, J.M.; Wallace, L.M.K.; Llewellyn, D.J.; Rockwood, K. Frailty, lifestyle, genetics and dementia risk. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2022, 93, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Jentoft, A.J.; Daragjati, J.; Fratiglioni, L.; Maggi, S.; Mangoni, A.A.; Mattace-Raso, F.; Paccalin, M.; Polidori, M.C.; Topinkova, E.; Ferrucci, L.; et al. Using the Multidimensional Prognostic Index (MPI) to improve cost-effectiveness of interventions in multimorbid frail older persons: Results and final recommendations from the MPI_AGE European Project. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2020, 32, 861–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Overbeek, F.C.M.S.; Goudzwaard, J.A.; van Hemmen, J.; van Bruchem-Visser, R.L.; Papma, J.M.; Polinder-Bos, H.A.; Mattace-Raso, F.U.S. The Multidimensional Prognostic Index Predicts Mortality in Older Outpatients with Cognitive Decline. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 2369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilotto, A.; Ferrucci, L.; Franceschi, M.; D’Ambrosio, L.P.; Scarcelli, C.; Cascavilla, L.; Paris, F.; Placentino, G.; Seripa, D.; Dallapiccola, B.; et al. Development and validation of a multidimensional prognostic index for one-year mortality from comprehensive geriatric assessment in hospitalized older patients. Rejuvenation Res. 2008, 11, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veronese, N.; Custodero, C.; Cella, A.; Demurtas, J.; Zora, S.; Maggi, S.; Barbagallo, M.; Sabbà, C.; Ferrucci, L.; Pilotto, A. Prevalence of multidimensional frailty and pre-frailty in older people in different settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res. Rev. 2021, 72, 101543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buscarnera, S.; Canevelli, M.; Bruno, G.; Garibotto, V.; Frisoni, G.B.; Ribaldi, F. Unraveling the link between frailty and Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers in patients with mild cognitive impairment. GeroScience 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sourdet, S.; Soriano, G.; Delrieu, J.; Steinmeyer, Z.; Guyonnet, S.; Saint-Aubert, L.; Payoux, P.; Ousset, P.J.; Ghisolfi, A.; Chicoulaa, B.; et al. Cognitive Function and Amyloid Marker in Frail Older Adults: The COGFRAIL Cohort Study. J. Frailty Aging 2021, 10, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngandu, T.; Lehtisalo, J.; Solomon, A.; Levälahti, E.; Ahtiluoto, S.; Antikainen, R.; Bäckman, L.; Hänninen, T.; Jula, A.; Laatikainen, T.; et al. A 2 Year Multidomain Intervention of Diet, Exercise, Cognitive Training, and Vascular Risk Monitoring versus Control to Prevent Cognitive Decline in At-Risk Elderly People (FINGER): A Randomised Controlled Trial. Lancet 2015, 385, 2255–2263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rascovsky, K.; Hodges, J.R.; Knopman, D.; Mendez, M.F.; Kramer, J.H.; Neuhaus, J.; van Swieten, J.C.; Seelaar, H.; Dopper, E.G.; Onyike, C.U.; et al. Sensitivity of revised diagnostic criteria for the behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia. Brain 2011, 134, 2456–2477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKeith, I.G.; Boeve, B.F.; Dickson, D.W.; Halliday, G.; Taylor, J.P.; Weintraub, D.; Aarsland, D.; Galvin, J.; Attems, J.; Ballard, C.G.; et al. Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: Fourth consensus report of the DLB Consortium. Neurology 2017, 89, 88–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachdev, P.; Kalaria, R.; O’Brien, J.; Skoog, I.; Alladi, S.; Black, S.E.; Blacker, D.; Blazer, D.G.; Chen, C.; Chui, H.; et al. Diagnostic criteria for vascular cognitive disorders: A VASCOG statement. Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord. 2014, 28, 206–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, S.M.; Galantucci, S.; Tartaglia, M.C.; Gorno-Tempini, M.L. The neural basis of syntactic deficits in primary progressive aphasia. Brain Lang. 2012, 122, 190–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansson, O.; Batrla, R.; Brix, B.; Carrillo, M.C.; Corradini, V.; Edelmayer, R.M.; Esquivel, R.N.; Hall, C.; Lawson, J.; Bastard, N.L.; et al. The Alzheimer’s Association international guidelines for handling of cerebrospinal fluid for routine clinical measurements of amyloid β and tau. Alzheimers Dement. 2021, 17, 1575–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Bryant, S.E.; Gupta, V.; Henriksen, K.; Edwards, M.; Jeromin, A.; Lista, S.; Bazenet, C.; Soares, H.; Lovestone, S.; Hampel, H.; et al. Guidelines for the standardization of preanalytic variables for blood-based biomarker studies in Alzheimer’s disease research. Alzheimers Dement. 2015, 11, 549–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roveta, F.; Rubino, E.; Marcinnò, A.; Grassini, A.; Piella, E.M.; Ferrandes, F.; Bonino, L.; Giaracuni, G.; Boschi, S.; Gioiello, G.; et al. Diagnostic performance of plasma biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease using a fully automated platform: A real-world clinical study. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2025, 13872877241313145, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folstein, M.F.; Robins, L.N.; Helzer, J.E. The Mini-Mental State Examination. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1983, 40, 812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasreddine, Z.S.; Phillips, N.A.; Bédirian, V.; Charbonneau, S.; Whitehead, V.; Collin, I.; Cummings, J.L.; Chertkow, H. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: A brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2005, 53, 695–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sunderland, T.; Hill, J.L.; Mellow, A.M.; Lawlor, B.A.; Gundersheimer, J.; Newhouse, P.A.; Grafman, J.H. Clock drawing in Alzheimer’s disease. A novel measure of dementia severity. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 1989, 37, 725–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, B.; Slachevsky, A.; Litvan, I.; Pillon, B. The FAB: A Frontal Assessment Battery at bedside. Neurology 2000, 55, 1621–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, S.; Ford, A.B.; Moskowitz, R.W.; Jackson, B.A.; Jaffe, M.W. studies of illness in the aged. the index of ADL: A standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. JAMA 1963, 185, 914–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawton, M.P.; Brody, E.M. Assessment of older people: Self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist 1969, 9, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfeiffer, E. A short portable mental status questionnaire for the assessment of organic brain deficit in elderly patients. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 1975, 23, 433–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Exton-Smith, A.N.; Sherwin, R.W. The prevention of pressure sores. Significance of spontaneous bodily movements. Lancet 1961, 2, 1124–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vellas, B.; Guigoz, Y.; Garry, P.J.; Nourhashemi, F.; Bennahum, D.; Lauque, S.; Albarede, J.L. The Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA) and its use in grading the nutritional state of elderly patients. Nutrition 1999, 15, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linn, B.S.; Linn, M.W.; Gurel, L. Cumulative illness rating scale. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 1968, 16, 622–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilotto, A.; Sancarlo, D.; Pellegrini, F.; Rengo, F.; Marchionni, N.; Volpato, S.; Ferrucci, L.; FIRI-SIGG Study Group. The Multidimensional Prognostic Index predicts in-hospital length of stay in older patients: A multicentre prospective study. Age Ageing 2016, 45, 90–96. [Google Scholar]

- González-Escalante, A.; Milà-Alomà, M.; Brum, W.S.; Ashton, N.J.; Ortiz-Romero, P.; Shekari, M.; Campo, M.D.; Anastasi, F.; Quijano-Rubio, C.; Kollmorgen, G.; et al. A plasma biomarker panel for detecting early amyloid-β accumulation and its changes in middle-aged cognitively unimpaired individuals at risk for Alzheimer’s disease. EBioMedicine 2025, 116, 105741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.M.; Wu, X.J.; Cao, J.; Jiao, J.; Chen, W. Association between Cognitive Frailty and Adverse Outcomes among Older Adults: A Meta-Analysis. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2022, 26, 817–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabbagh, M.N.; Lue, L.F.; Fayard, D.; Shi, J. Increasing Precision of Clinical Diagnosis of Alzheimer’s Disease Using a Combined Algorithm Incorporating Clinical and Novel Biomarker Data. Neurol. Ther. 2017, 6 (Suppl. 1), 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nader, M.M.; Cosarderelioglu, C.; Miao, E.; Whitson, H.; Xue, Q.L.; Grodstein, F.; Oh, E.; Ferrucci, L.; Bennett, D.A.; Walston, J.D.; et al. Navigating and Diagnosing Cognitive Frailty in Research and Clinical Domains. Nat. Aging 2023, 3, 1325–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallace, L.; Theou, O.; Rockwood, K.; Andrew, M.K. Relationship between Frailty and Alzheimer’s Disease Biomarkers: A Scoping Review. Alzheimers Dement. 2018, 10, 394–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Non-AD | AD | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 66.2 ± 9.60 | 69.8 ± 8.21 | 0.139 |

| Sex | 7 (35%) | 10 (50%) | 0.343 |

| Education | 11.7 ± 3.39 | 11.3 ± 3.50 | 0.569 |

| CSF Aβ42 | 722 ± 312 | 340 ± 149 | <0.001 |

| CSF Aβ42/40 ratio | 0.0794 ± 0.0146 | 0.0417 ± 0.0116 | <0.001 |

| CSF Tau | 370 ± 149 | 644 ± 308 | 0.001 |

| CSF p-tau181 | 45.3 ± 29.3 | 113 ± 58 | <0.001 |

| LCS NfL | 2269 ± 2906 | 1107 ± 704 | 0.417 |

| plasma Aβ42 | 27.9 ± 7.41 | 22.8 ± 8.81 | 0.026 |

| plasma Aβ42/40 ratio | 0.0925 ± 0.0133 | 0.0765 ± 0.0107 | <0.001 |

| plasma p-tau181 | 0.927 ± 0.294 | 2.33 ± 1.15 | <0.001 |

| plasma NfL | 40.6 ± 35.6 | 30.5 ± 15.2 | 0.626 |

| MPI | 0.188, 0.0625–0.203 | 0.250, 0.188–0.328 | 0.031 |

| ADL | 6, 6–6 | 6, 6–6 | 0.668 |

| IADL | 8, 7–8 | 7, 4.75–8 | 0.090 |

| ESS | 20, 19,8–20 | 20, 19,8–20 | 0.921 |

| SPMSQ | 1, 1–2 | 2, 1–5 | 0.021 |

| MNA | 12, 11–14 | 12, 11–14 | 0.687 |

| CIRS-CI | 2, 0.75–2.25 | 2.50, 1–3 | 0.589 |

| NUMBER OF DRUGS | 2, 2–3 | 2.50, 2–5.25 | 0.205 |

| SOCIAL CONDITION | 0, 0–1 | 0, 0–0.5 | 0.478 |

| MMSE | 25.7 ± 4.71 | 21.6 ± 7.61 | 0.027 |

| MoCA | 19.4 ± 4.83 | 16.8 ± 5.70 | 0.204 |

| FAB | 13.1 ± 3.80 | 11.8 ± 3.56 | 0.269 |

| CLOCK | 10.6 ± 3.08 | 9.35 ± 4.53 | 0.420 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cermelli, A.; Crisafi, A.; Chiarandon, A.M.; Mirabelli, G.; Lombardo, C.; Batti, V.; Boschi, S.; Piella, E.M.; Roveta, F.; Rainero, I.; et al. Exploring Frailty Status and Blood Biomarkers: A Multidimensional Approach to Alzheimer’s Diagnosis. Geriatrics 2025, 10, 133. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics10050133

Cermelli A, Crisafi A, Chiarandon AM, Mirabelli G, Lombardo C, Batti V, Boschi S, Piella EM, Roveta F, Rainero I, et al. Exploring Frailty Status and Blood Biomarkers: A Multidimensional Approach to Alzheimer’s Diagnosis. Geriatrics. 2025; 10(5):133. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics10050133

Chicago/Turabian StyleCermelli, Aurora, Armando Crisafi, Alberto Mario Chiarandon, Giorgia Mirabelli, Chiara Lombardo, Virginia Batti, Silvia Boschi, Elisa Maria Piella, Fausto Roveta, Innocenzo Rainero, and et al. 2025. "Exploring Frailty Status and Blood Biomarkers: A Multidimensional Approach to Alzheimer’s Diagnosis" Geriatrics 10, no. 5: 133. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics10050133

APA StyleCermelli, A., Crisafi, A., Chiarandon, A. M., Mirabelli, G., Lombardo, C., Batti, V., Boschi, S., Piella, E. M., Roveta, F., Rainero, I., & Rubino, E. (2025). Exploring Frailty Status and Blood Biomarkers: A Multidimensional Approach to Alzheimer’s Diagnosis. Geriatrics, 10(5), 133. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics10050133