Sleep Disturbances and Dementia in the UK South Asian Community: A Qualitative Study to Inform Future Adaptation of the DREAMS-START Intervention

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Ethics

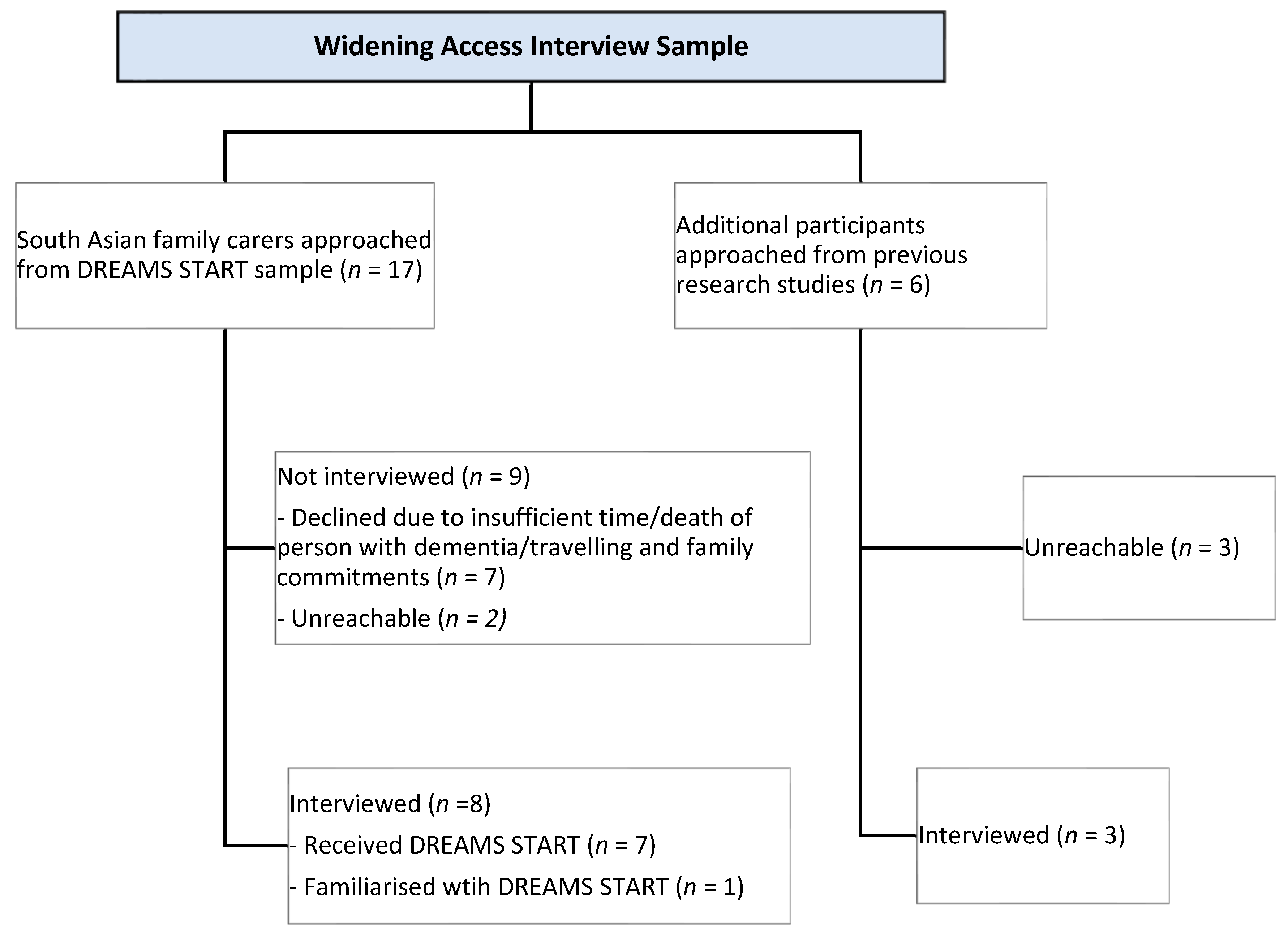

2.2. Procedures

2.2.1. Participants

2.2.2. Qualitative Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

2.4. Researcher Reflexivity

2.5. Translating DREAMS-START Manuals into Hindi

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

3.2. Qualitative Findings

- Theme 1: The impact of dementia-related sleep disturbance in South Asian familiesSub-theme 1: Sleep disturbances in South Asian multigenerational households

We found that she was coming out of her room more and more and going down the stairs […] someone was always awake or going after her […] We had our door open, we had mum’s door open, and the kids would be up, so they’d listen out for mum, they might put her back into bed […] I mean there were times when none of us got any sleep.(Daughter-in-law)

I was getting very depressed myself. My whole family was suffering. I had a teenage daughter, she was feeling neglected […] you know, all the energy was going.(Daughter2)

We think her [relative with dementia] sleep has been affected, I mean, you need to know that we live on one floor… It is a four-bedroom flat… The problem is every bedroom door, […] is almost next to each other… If you touch one door, the person sleeping in the other room… will be affected. I think this is how it all started and then slowly it only got worse.(Son2)

- Sub-theme 2: The impact of family relationships and cultural expectations on sleep management

The fact that I’m saying, going against my Mum, right. So, for a child to start caring for the mum… a role reversal, it’s not gone down well. It’s hard for me being the son to tell my Mum or suggest things.(Son4)

My husband would then stay in her room and say Mum go to sleep, and I think she saw him an authoritative figure type of thing. She saw him as a brother, she forgot that he was her son, and she’d call him “bhaiyya”, meaning brother […] she would say yes bhaiyya, yes bhaiyya, I’ll do whatever you say Bhaiyya.(Daughter-in-law)

If it’s a woman [family carer], they usually don’t like carers coming in, they expect the families to help out—the daughter-in-law or the women in the house help out. So, … if things get really bad… I know some Asian families where they just struggle.(Daughter2)

Not outside people… So, blood relatives are fine, you know, brothers, his brothers, your sisters, you know, blood relatives know it, and that’s completely fine. Community people don’t need to know.(Son2)

I think understanding that… having a component, addressing that issue of how women in the South Asian community, that they’re seen as being carers anyway and that how do you help them understand that, that they can ask for support and help?(Daughter4)

With the Asian community when say somebody has dementia, they don’t take them out as much […] so maybe encouragement of having something more outside the house as well, different activities […] I don’t know how people would be encouraged to go outside, because I know lot of people with an Asian background, when somebody’s got dementia, they’re usually in the house.(Daughter2)

- Sub-theme 3: Working together to address sleep disturbance

I’d be saying to the family, let’s work together … you know, if there was a particularly noisy family member, saying you need to keep the noise down because grandmother needs to sleep or. So yeah, I think, it would be essential to pass on the information that you were getting onto other family members as well.(Daughter1)

It would be completely different if this was just me on my own caring, and my brother wasn’t around. I would have had to change my life completely […] we’d have to sort of reorganize the house and make sure the downstairs is secure and…for the showering and… downstairs and… it would have a big impact for… we were just lucky the way we were able to kind of organize things.(Daughter1)

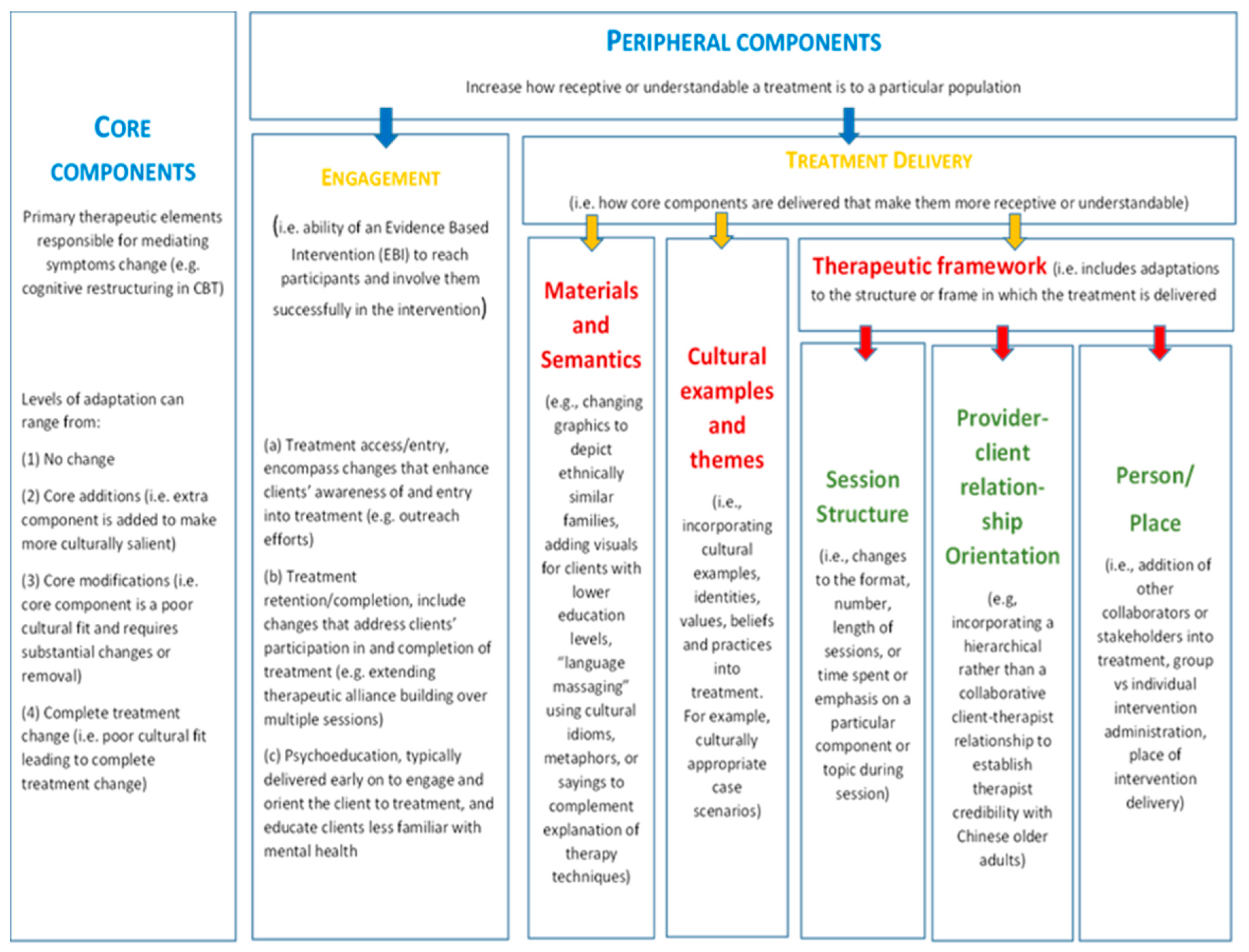

- Theme 2: Considerations for cultural adaptation of DREAMS-STARTSub-theme 1: Linguistic adaptation of DREAMS-START

It may help those where English isn’t their first language. Because you lose certain, certain nuances, don’t you?(Daughter3)

language is the main thing right. There are many things that we don’t understand as well in English as we would in our own language. There’s that difference, of course. Even for the sessions, I didn’t find any benefit […] I understood half, I didn’t understand half… it’s a waste of time.(Wife2)

it’s also best to give them the English version as well. So, you give them both. So at least if you can’t understand yourself in that Bengali language, you can ask your son or your daughter… and they can explain it to you.(Son2)

- Sub-theme 2: Cultural competence of DREAMS-START facilitators

It can work to the person’s advantage, if the person is also from the same culture or some similar culture…. Because there’s this kind of shared understanding of how families operate […] I don’t know whether the family would feel embarrassed to say to someone of the different culture. But […] it’s the attitude of the person doing the intervention to just be able to [unclear] and not be judgemental… and accepting of different ways of living.(Daughter1)

As long as they can communicate, like, I’m from an Indian background, I had a White male speaking to me, it didn’t matter that we had different cultures; it mattered that he could communicate well to me and understand my issues.(Daughter2)

- Sub-theme 3: Potential adaptations of DREAMS-START content

“it would probably reflect more the sorts of things that people from South Asian families might say…”.(Daughter1)

Most of [DREAMS START manuals] use examples about English people, so to speak. And if part of it is slightly changed to the culture of the individual, then that would be helpful.(Son3)

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Findings

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

4.3. Recommendations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Koren, T.; Fisher, E.; Webster, L.; Livingston, G.; Rapaport, P. Prevalence of sleep disturbances in people with dementia living in the community: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res. Rev. 2023, 83, 101782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, M.; Lynch, C.; Walsh, C.; Coen, R.; Coakley, D.; Lawlor, B. Sleep disturbance in mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease. Sleep Med. 2005, 6, 347–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wennberg, A.M.; Wu, M.N.; Rosenberg, P.B.; Spira, A.P. Sleep disturbance, cognitive decline, and dementia: A review. In Seminars in Neurology; Thieme Medical Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wimo, A.; Gauthier, S.; Prince, M. Global Estimates of Informal Care; Alzheimer’s Disease International: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Gehrman, P.; Gooneratne, N.S.; Brewster, G.S.; Richards, K.C.; Karlawish, J. Impact of Alzheimer disease patients’ sleep disturbances on their caregivers. Geriatr. Nurs. 2018, 39, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Creese, J.; Bédard, M.; Brazil, K.; Chambers, L. Sleep disturbances in spousal caregivers of individuals with Alzheimer’s disease. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2008, 20, 149–161. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Reinhard, S.C.; Given, B.; Petlick, N.H.; Bemis, A. Supporting family caregivers in providing care. In Patient Safety and Quality: An Evidence-Based Handbook for Nurses; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Rockville, MD, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Brewster, G.S.; Wang, D.; McPhillips, M.V.; Epps, F.; Yang, I. Correlates of Sleep Disturbance Experienced by Informal Caregivers of Persons Living with Dementia: A Systematic Review. Clin. Gerontol. 2024, 47, 380–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilfling, D.; Hylla, J.; Berg, A.; Meyer, G.; Köpke, S.; Halek, M.; Möhler, R.; Dichter, M.N. Characteristics of multicomponent, nonpharmacological interventions to reduce or avoid sleep disturbances in nursing home residents: A systematic review. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2021, 33, 245–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NICE. Dementia: Assessment, Management and Support for People Living with Dementia and Their Carers; NICE: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Dichter, M.N.; Dörner, J.; Wilfling, D.; Berg, A.; Klatt, T.; Möhler, R.; Haastert, B.; Meyer, G.; Halek, M.; Köpke, S. Intervention for sleep problems in nursing home residents with dementia: A cluster-randomized study. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2024, 36, 965–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rapaport, P.; Amador, S.; Adeleke, M.O.; Barber, J.A.; Banerjee, S.; Charlesworth, G.; Clarke, C.; Espie, C.A.; Gonzalez, L.; Horsley, R.; et al. Clinical effectiveness of DREAMS START (Dementia Related Manual for Sleep; Strategies for Relatives) versus usual care for people with dementia and their carers: A single-masked, phase 3, parallel-arm, superiority randomised controlled trial. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2024, 5, 100635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amador, S.; Livingston, G.; Adeleke, M.; Barber, J.; Webster, L.; Yuan, H.; Banerjee, S.; Bhojwani, A.; Charlesworth, G.; Clarke, C.; et al. Process evaluation in a randomised controlled trial of DREAMS-START (dementia related manual for sleep; strategies for relatives) for sleep disturbance in people with dementia and their carers. Age Ageing 2025, 54, afaf053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, A.R.; Perales-Puchalt, J.; Johnson, E.; Espinoza-Kissell, P.; Acosta-Rullan, M.; Frederick, S.; Lewis, A.; Chang, H.; Mahnken, J.; Vidoni, E.D. Representation of racial and ethnic minority populations in dementia prevention trials: A systematic review. J. Prev. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2022, 9, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waheed, W.; Mirza, N.; Waheed, M.W.; Blakemore, A.; Kenning, C.; Masood, Y.; Matthews, F.; Bower, P. Recruitment and methodological issues in conducting dementia research in British ethnic minorities: A qualitative systematic review. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 2020, 29, e1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, R.; Amano, T.; Lin, S.-Y.; Zhou, Y.; Morrow-Howell, N. Strategies for the recruitment and retention of racial/ethnic minorities in Alzheimer disease and dementia clinical research. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2019, 16, 458–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, S.G.; Al-Jaishi, A.A.; Niznick, H.; Carroll, K.; Madani, M.T.; Peak, K.D.; Madani, L.; Nevins, P.; Adisso, L.; Li, F.; et al. Health equity considerations in pragmatic trials in Alzheimer’s and dementia disease: Results from a methodological review. Alzheimer’s Dement. Diagn. Assess. Dis. Monit. 2023, 15, e12392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukadam, N.; Marston, L.; Lewis, G.; Mathur, R.; Rait, G.; Livingston, G. Incidence, age at diagnosis and survival with dementia across ethnic groups in England: A longitudinal study using electronic health records. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2023, 19, 1300–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ownby, R.L.; Saeed, M.; Wohlgemuth, W.; Capasso, R.; Acevedo, A.; Peruyera, G.; Sevush, S. Caregiver reports of sleep problems in non-Hispanic white, Hispanic, and African American patients with Alzheimer dementia. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2010, 6, 281–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallagher, V.T.; Reilly, S.E.; Williams, I.C.; Mattos, M.; Manning, C. Patterns of sleep disturbances across stages of cognitive decline. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2023, 38, e5865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NIHR. Improving Inclusion of Under-Served Groups in Clinical Research: Guidance from the NIHR-INCLUDE Project; NIHR: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lillekroken, D.; Halvorsrud, L.; Gulestø, R.; Bjørge, H. Family caregivers’ experiences of providing care for family members from minority ethnic groups living with dementia: A qualitative systematic review. J. Clin. Nurs. 2023, 32, 1625–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukadam, N.; Cooper, C.; Basit, B.; Livingston, G. Why do ethnic elders present later to UK dementia services? A qualitative study. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2011, 23, 1070–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukadam, N.; Waugh, A.; Cooper, C.; Livingston, G. What would encourage help-seeking for memory problems among UK-based South Asians? A qualitative study. BMJ Open 2015, 5, e007990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giebel, C.M.; Zubair, M.; Jolley, D.; Bhui, K.S.; Purandare, N.; Worden, A.; Challis, D. South Asian older adults with memory impairment: Improving assessment and access to dementia care. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2015, 30, 345–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, T.; Mukadam, N.; Sommerlad, A.; Barrera-Caballero, S.; Livingston, G. Equity in care and support provision for people affected by dementia: Experiences of people from UK South Asian and White British backgrounds. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2023, 36, 564–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, L.; Amador, S.; Rapaport, P.; Mukadam, N.; Sommerlad, A.; James, T.; Javed, S.; Roche, M.; Lord, K.; Bharadia, T. Tailoring STrAtegies for RelaTives for Black and South Asian dementia family carers in the United Kingdom: A mixed methods study. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2023, 38, e5868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 2019, 11, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, J.; Leino, A. Advancement in the maturing science of cultural adaptations of evidence-based interventions. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2017, 85, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, B.; Basnet, M.; Rimal, P.; Citrin, D.; Hirachan, S.; Swar, S.; Thapa, P.; Pandit, J.; Pokharel, R.; Kohrt, B. Translating mental health diagnostic and symptom terminology to train health workers and engage patients in cross-cultural, non-English speaking populations. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 2017, 11, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maríñez-Lora, A.M.; Boustani, M.; Del Busto, C.T.; Leone, C. A framework for translating an evidence-based intervention from English to Spanish. Hisp. J. Behav. Sci. 2016, 38, 117–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, S.P.; Dev, R.; Shrestha, J.N.R. Cross-cultural adaptation, validity, and reliability of the Nepali version of the Exercise Adherence Rating Scale: A methodological study. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2020, 18, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jutlla, K.; Kaur, H. The Experience of Dementia in UK South Asian Communities. In Supporting People Living with Dementia in Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic Communities: Key Issues and Strategies for Change; Jessica Kingsley Publishers: London, UK, 2019; p. 55. [Google Scholar]

- Herat-Gunaratne, R.; Cooper, C.; Mukadam, N.; Rapaport, P.; Leverton, M.; Higgs, P.; Samus, Q.; Burton, A. “In the Bengali vocabulary, there is no such word as care home”: Caring experiences of UK Bangladeshi and Indian family carers of people living with dementia at home. Gerontologist 2020, 60, 331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katbamna, S.; Ahmad, W.; Bhakta, P.; Baker, R.; Parker, G. Do they look after their own? Informal support for South Asian carers. Health Soc. Care Community 2004, 12, 398–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Pillai, V.K. Elder caregiving in South-Asian families in the United States and India. Soc. Work. Soc. 2012, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborti, R.D. The Greying of India: Population Ageing in the Context of Asia; Sage: Singapore, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, L.J.; Marx, K.A.; Nkimbeng, M.; Johnson, E.; Koeuth, S.; Gaugler, J.E.; Gitlin, L.N. It’s more than language: Cultural adaptation of a proven dementia care intervention for Hispanic/Latino caregivers. Gerontologist 2023, 63, 558–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resnicow, K.; Baranowski, T.; Ahluwalia, J.S.; Braithwaite, R.L. Cultural sensitivity in public health: Defined and demystified. Ethn. Dis. 1999, 9, 10–21. [Google Scholar]

- Mackenzie, J. Stigma and dementia: East European and South Asian family carers negotiating stigma in the UK. Dementia 2006, 5, 233–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poole, C.; Harrison, J.; Hill, J. Understanding dementia in South Asian populations: An exploration of knowledge and awareness. Br. J. Neurosci. Nurs. 2021, 17, 156–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sousa, V.D.; Rojjanasrirat, W. Translation, adaptation and validation of instruments or scales for use in cross-cultural health care research: A clear and user-friendly guideline. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2011, 17, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sample Characteristic | Category | n (%) or Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 58.8 (10.64) | |

| Sex | Male | 4 (36%) |

| Female | 7 (64%) | |

| First language | English | 9 (82%) |

| Bengali/Sylheti | 1 (9%) | |

| Punjabi | 1(9%) | |

| Ethnicity | Asian/British Asian (Indian) | 9 (82%) |

| Asian/British Asian (Bangladeshi) | 1 (9%) | |

| Asian/British Asian (Sri Lankan) | 1 (9%) | |

| Relationship to person with dementia | Spouse | 2 (18%) |

| Child | 8 (73%) | |

| Daughter-in-law | 1 (9%) | |

| Carer cohabiting with relative when actively caring at home | Yes | 8 (73%) |

| Caregiving status at the time of interview | Caring for relative at home | 6 (55%) |

| Relative in care home | 3 (27%) | |

| Ex-carer (Relative died) | 2 (18%) | |

| Multigenerational household | Yes | 7 (64%) |

| Education | High-school diploma | 3 (27%) |

| Undergraduate degree | 5 (45%) | |

| Postgraduate degree | 3 (27%) | |

| Employment | Full-time | 3 (27%) |

| Part-time | 3 (27%) | |

| Unemployed | 4 (36%) | |

| Retired | 1 (9%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rapaport, P.; Muralidhar, M.; Amador, S.; Mukadam, N.; Bhojwani, A.; Beeson, C.; Livingston, G. Sleep Disturbances and Dementia in the UK South Asian Community: A Qualitative Study to Inform Future Adaptation of the DREAMS-START Intervention. Geriatrics 2025, 10, 121. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics10050121

Rapaport P, Muralidhar M, Amador S, Mukadam N, Bhojwani A, Beeson C, Livingston G. Sleep Disturbances and Dementia in the UK South Asian Community: A Qualitative Study to Inform Future Adaptation of the DREAMS-START Intervention. Geriatrics. 2025; 10(5):121. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics10050121

Chicago/Turabian StyleRapaport, Penny, Malvika Muralidhar, Sarah Amador, Naaheed Mukadam, Ankita Bhojwani, Charles Beeson, and Gill Livingston. 2025. "Sleep Disturbances and Dementia in the UK South Asian Community: A Qualitative Study to Inform Future Adaptation of the DREAMS-START Intervention" Geriatrics 10, no. 5: 121. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics10050121

APA StyleRapaport, P., Muralidhar, M., Amador, S., Mukadam, N., Bhojwani, A., Beeson, C., & Livingston, G. (2025). Sleep Disturbances and Dementia in the UK South Asian Community: A Qualitative Study to Inform Future Adaptation of the DREAMS-START Intervention. Geriatrics, 10(5), 121. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics10050121