Comprehensive Strategies for Preventive Periodontal Care in Older Adults

Abstract

:1. Introduction

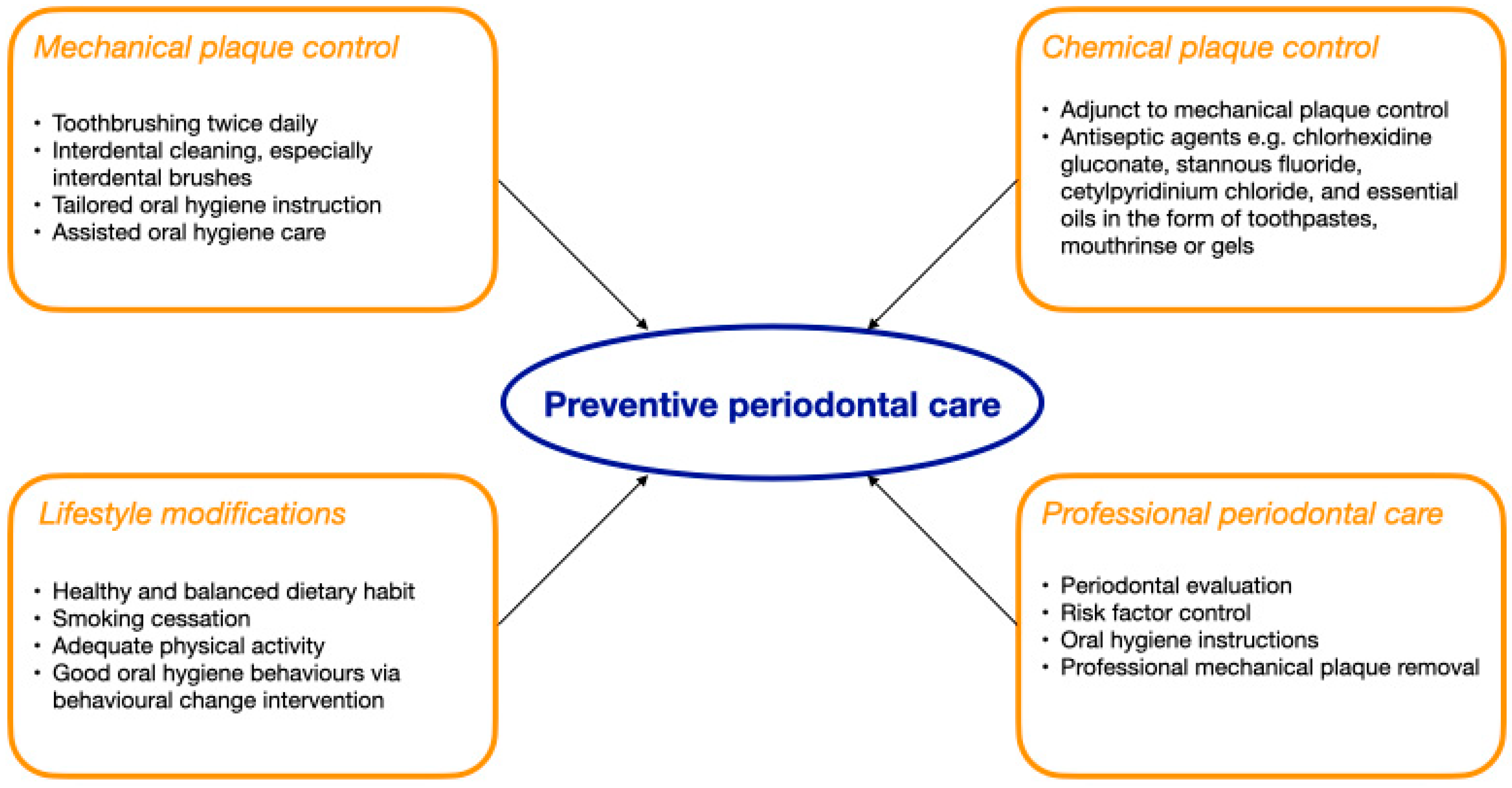

2. Preventive Periodontal Care for Older Adults

2.1. Mechanical Plaque Control

2.1.1. Toothbrushing

2.1.2. Interdental Cleaning

2.1.3. Tailored Oral Hygiene Instruction

2.1.4. Assisted Oral Hygiene Care

2.1.5. Professional Mechanical Plaque Control

2.2. Use of Chemotherapeutic Agents

2.2.1. Chlorhexidine Gluconate

2.2.2. Stannous Fluoride

2.2.3. Cetylpyridinium Chloride

2.2.4. Essential Oils

2.3. Lifestyle Modifications

2.3.1. Dietary Habit

2.3.2. Smoking

2.3.3. Physical Activity

2.3.4. Oral Hygiene Habits

2.3.4.1. The 5S Methodology

2.4. Regular Professional Periodontal Care

3. Public Health Initiatives for Preventive Periodontal Care

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Population Ageing 2019. United Nations Digital Library System. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/ageing/WorldPopulationAgeing2019-Report.pdf (accessed on 8 March 2025).

- Genco, R.J.; Sanz, M. Clinical and public health implications of periodontal and systemic diseases: An overview. Periodontol. 2000 2020, 83, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The World Health Organization. World Report on Ageing and Health. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/186463/9789240694811_eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 8 March 2025).

- Samietz, S.; Wöstmann, B.; Kuhr, K.; Jordan, A.R.; Stark, H.; Nitschke, I. Oral health in the elderly: Results of the 6th German Oral Health Study (DMS • 6). Quintessence Int. 2025, 56, S112–S119. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wang, X. The Fourth National Oral Health Epidemiological Survey Report; People’s Medical Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2018; pp. 13–14. [Google Scholar]

- Papapanou, P.N.; Sanz, M.; Buduneli, N.; Dietrich, T.; Feres, M.; Fine, D.H.; Flemmig, T.F.; Garcia, R.; Giannobile, W.V.; Graziani, F.; et al. Periodontitis: Consensus report of workgroup 2 of the 2017 World Workshop on the Classification of Periodontal and Peri-Implant Diseases and Conditions. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2018, 45 (Suppl. S20), S162–S170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, A.K.Y.; Tamrakar, M.; Jiang, C.M.; Lo, E.C.M.; Leung, K.C.M.; Chu, C.H. Common Medical and Dental Problems of Older Adults: A Narrative Review. Geriatrics 2021, 6, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, G.L.K.; Tan, M.N.; Wong, M.L.; Tay, C.M.; Allen, P.F. Functional Dentition, Chronic Periodontal Disease and Frailty in Older Adults—A Narrative Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2022, 20, 502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preshaw, P.M.; Alba, A.L.; Herrera, D.; Jepsen, S.; Konstantinidis, A.; Makrilakis, K.; Taylor, R. Periodontitis and diabetes: A two-way relationship. Diabetologia 2012, 55, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tonetti, M.S.; Bottenberg, P.; Conrads, G.; Eickholz, P.; Heasman, P.; Huysmans, M.C.; López, R.; Madianos, P.; Müller, F.; Needleman, I.; et al. Dental caries and periodontal diseases in the ageing population: Call to action to protect and enhance oral health and well-being as an essential component of healthy ageing—Consensus report of group 4 of the joint EFP/ORCA workshop on the boundaries between caries and periodontal diseases. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2017, 44 (Suppl. S18), S135–S144. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, C.C.K.; Chan, A.K.Y.; Chu, C.H.; Tsang, Y.C. Theory-based behavioral change interventions to improve periodontal health. Front. Oral Health 2023, 4, 1067092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonetti, M.S.; Eickholz, P.; Loos, B.G.; Papapanou, P.; van der Velden, U.; Armitage, G.; Bouchard, P.; Deinzer, R.; Dietrich, T.; Hughes, F.; et al. Principles in prevention of periodontal diseases: Consensus report of group 1 of the 11th European Workshop on Periodontology on effective prevention of periodontal and peri-implant diseases. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2015, 42 (Suppl. S16), S5–S11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz, M.; Herrera, D.; Kebschull, M.; Chapple, I.; Jepsen, S.; Beglundh, T.; Sculean, A.; Tonetti, M.S. Treatment of stage I-III periodontitis-The EFP S3 level clinical practice guideline. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2020, 47 (Suppl. 22), 4–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapple, I.L.; Van der Weijden, F.; Doerfer, C.; Herrera, D.; Shapira, L.; Polak, D.; Madianos, P.; Louropoulou, A.; Machtei, E.; Donos, N.; et al. Primary prevention of periodontitis: Managing gingivitis. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2015, 42 (Suppl. 16), S71–S76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Worthington, H.V.; MacDonald, L.; Poklepovic Pericic, T.; Sambunjak, D.; Johnson, T.M.; Imai, P.; Clarkson, J.E. Home use of interdental cleaning devices, in addition to toothbrushing, for preventing and controlling periodontal diseases and dental caries. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 4, Cd012018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ju, L.Y.; Weng, S.C.; Chung, Y.J.; Yang, S.H.; Huang, Y.H.; Huang, L.G.; Chin, C.S.; Hoogland, A.I.; Chang, P.H. Effects of the bass brushing method on dental plaque and pneumonia in older adults hospitalized with pneumonia after discharge: A randomized controlled trial. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2019, 46, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, C.H.; Lin, C.H.; Ma, T.L.; Peng, T.Y.; Vo, T.T.T.; Lin, W.N.; Chen, Y.H.; Lee, I.T. Comparison Between Powered and Manual Toothbrushes Effectiveness for Maintaining an Optimal Oral Health Status. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dent. 2024, 16, 381–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobre, C.V.C.; Gomes, A.M.M.; Gomes, A.P.M.; Gomes, A.A.; Nascimento, A.P.C. Assessment of the efficacy of the utilisation of conventional and electric toothbrushes by the older adults. Gerodontology 2020, 37, 297–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fjeld, K.G.; Eide, H.; Mowe, M.; Sandvik, L.; Willumsen, T. A 1-year follow-up of a randomized clinical trial with focus on manual and electric toothbrushes’ effect on dental hygiene in nursing homes. Acta Odontol. Scand. 2018, 76, 257–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, M.A.; Kellett, M.; Worthington, H.V.; Clerehugh, V. Comparison of interdental cleaning methods: A randomized controlled trial. J. Periodontol. 2006, 77, 1421–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotsakis, G.A.; Lian, Q.; Ioannou, A.L.; Michalowicz, B.S.; John, M.T.; Chu, H. A network meta-analysis of interproximal oral hygiene methods in the reduction of clinical indices of inflammation. J. Periodontol. 2018, 89, 558–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, C.R.; Lyle, D.M.; Qaqish, J.G.; Schuller, R. Evaluation of the plaque removal efficacy of a water flosser compared to string floss in adults after a single use. J. Clin. Dent. 2013, 24, 37–42. [Google Scholar]

- Chau, R.C.W.; Thu, K.M.; Chaurasia, A.; Hsung, R.T.C.; Lam, W.Y. A Systematic Review of the Use of mHealth in Oral Health Education among Older Adults. Dent. J. 2023, 11, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buck, D.; Seong, J.; Daud, A.; Davies, M.; Newcombe, R.; West, N.X. A randomised controlled trial to evaluate the effectiveness of personalised oral hygiene advice delivered via video technology. J. Dent. 2024, 149, 105243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Nasser, L.; Lamster, I.B. Prevention and management of periodontal diseases and dental caries in the older adults. Periodontol. 2000 2020, 84, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, R.A.; Wang, J.; Plassman, B.L.; Nye, K.; Bunn, M.; Poole, P.; Drake, C.; Xu, H.; Ni, Z.; Wu, B. Working together to learn new oral hygiene techniques: Pilot of a carepartner-assisted intervention for persons with cognitive impairment. Geriatr. Nurs. 2019, 40, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, B.; Anderson, R.A.; Pei, Y.; Xu, H.; Nye, K.; Poole, P.; Bunn, M.; Lynn Downey, C.; Plassman, B.L. Care partner-assisted intervention to improve oral health for older adults with cognitive impairment: A feasibility study. Gerodontology 2021, 38, 308–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figuero, E.; Roldán, S.; Serrano, J.; Escribano, M.; Martín, C.; Preshaw, P.M. Efficacy of adjunctive therapies in patients with gingival inflammation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2020, 47 (Suppl. 22), 125–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brecx, M. Strategies and agents in supragingival chemical plaque control. Periodontol. 2000 1997, 15, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, P.; Worthington, H.V.; Parnell, C.; Harding, M.; Lamont, T.; Cheung, A.; Whelton, H.; Riley, P. Chlorhexidine mouthrinse as an adjunctive treatment for gingival health. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 3, Cd008676. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jenkins, S.; Addy, M.; Newcombe, R.G. Dose response of chlorhexidine against plaque and comparison with triclosan. J. Clin. Periodontol. 1994, 21, 250–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figuero, E.; Serrano, J.; Arweiler, N.B.; Auschill, T.M.; Gürkan, A.; Emingil, G. Supra and subgingival application of antiseptics or antibiotics during periodontal therapy. Periodontol. 2000, 2023; Online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Weijden, F.A.; Van der Sluijs, E.; Ciancio, S.G.; Slot, D.E. Can Chemical Mouthwash Agents Achieve Plaque/Gingivitis Control? Dent. Clin. N. Am. 2015, 59, 799–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haps, S.; Slot, D.E.; Berchier, C.E.; Van der Weijden, G.A. The effect of cetylpyridinium chloride-containing mouth rinses as adjuncts to toothbrushing on plaque and parameters of gingival inflammation: A systematic review. Int. J. Dent. Hyg. 2008, 6, 290–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Leeuwen, M.P.; Slot, D.E.; Van der Weijden, G.A. Essential oils compared to chlorhexidine with respect to plaque and parameters of gingival inflammation: A systematic review. J. Periodontol. 2011, 82, 174–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramseier, C.A.; Woelber, J.P.; Kitzmann, J.; Detzen, L.; Carra, M.C.; Bouchard, P. Impact of risk factor control interventions for smoking cessation and promotion of healthy lifestyles in patients with periodontitis: A systematic review. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2020, 47 (Suppl. 22), 90–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, A.K.Y.; Tsang, Y.C.; Jiang, C.M.; Leung, K.C.M.; Lo, E.C.M.; Chu, C.H. Diet, Nutrition, and Oral Health in Older Adults: A Review of the Literature. Dent. J. 2023, 11, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapple, I.L.; Bouchard, P.; Cagetti, M.G.; Campus, G.; Carra, M.C.; Cocco, F.; Nibali, L.; Hujoel, P.; Laine, M.L.; Lingstrom, P.; et al. Interaction of lifestyle, behaviour or systemic diseases with dental caries and periodontal diseases: Consensus report of group 2 of the joint EFP/ORCA workshop on the boundaries between caries and periodontal diseases. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2017, 44 (Suppl. S18), S39–S51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, J.P.; Milledge, K.L.; O’Leary, F.; Cumming, R.; Eberhard, J.; Hirani, V. Poor dietary intake of nutrients and food groups are associated with increased risk of periodontal disease among community-dwelling older adults: A systematic literature review. Nutr. Rev. 2020, 78, 175–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salmi, A.; Komulainen, K.; Nihtilä, A.; Tiihonen, M.; Nykänen, I.; Hartikainen, S.; Suominen, A.L. Eating problems among old home care clients. Clin. Exp. Dent. Res. 2022, 8, 959–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelig, R.; Goldstein, S.; Touger-Decker, R.; Firestone, E.; Golden, A.; Johnson, Z.; Kaseta, A.; Sackey, J.; Tomesko, J.; Parrott, J.S. Tooth loss and nutritional status in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JDR Clin. Trans. Res. 2022, 7, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sire, A.; Ferrillo, M.; Lippi, L.; Agostini, F.; de Sire, R.; Ferrara, P.E.; Raguso, G.; Riso, S.; Roccuzzo, A.; Ronconi, G.; et al. Sarcopenic dysphagia, malnutrition, and oral frailty in elderly: A comprehensive review. Nutrients 2022, 14, 982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nociti, F.H., Jr.; Casati, M.Z.; Duarte, P.M. Current perspective of the impact of smoking on the progression and treatment of periodontitis. Periodontol. 2000 2015, 67, 187–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO Monograph on Tobacco Cessation and Oral Health Integration. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/255692/9789241512671-eng.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 8 March 2025).

- Clinical Practice Guideline Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence 2008 Update Panel, Liaisons, and Staff. A clinical practice guideline for treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update: A US public health service report. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2008, 35, 158–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, A.K.Y.; Tsang, Y.C.; Jiang, C.M.; Leung, K.C.M.; Lo, E.C.M.; Chu, C.H. Integration of Oral Health into General Health Services for Older Adults. Geriatrics 2023, 8, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tackling NCDs: Best Buys and Other Recommended Interventions for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/259232/WHO-NMH-NVI-17.9-eng.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 8 March 2025).

- Chan, C.C.K.; Chan, A.K.Y.; Chu, C.H.; Tsang, Y.C. Physical activity as a modifiable risk factor for periodontal disease. Front. Oral Health 2023, 4, 1266462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, S.J.; Bae, K.H.; Lee, H.J.; Kim, S.J.; Cho, H.J. Association between regular walking and periodontitis according to socioeconomic status: A cross-sectional study. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 12969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grönbeck Lindén, I.; Hägglin, C.; Gahnberg, L.; Andersson, P. Factors Affecting Older Persons’ Ability to Manage Oral Hygiene: A Qualitative Study. JDR Clin. Trans. Res. 2017, 2, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.S.; Chu, C.H.; Young, F.Y.F. Integrating 5S Methodology into Oral Hygiene Practice for Elderly with Alzheimer’s Disease. Dent. J. 2020, 8, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirano, H. 5 Pillars of the Visual Workplace, 1st ed.; Productivity Press: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, A.K.Y.; Chu, C.H.; Ogawa, H.; Lai, E.H. Improving oral health of older adults for healthy ageing. J. Dent. Sci. 2024, 19, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, D.; Meyle, J.; Renvert, S.; Jin, L. White Paper on Prevention and Management of Periodontal Diseases for Oral Health and General Health; FDI World Dental Federation: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lang, N.P.; Tonetti, M.S. Periodontal risk assessment (PRA) for patients in supportive periodontal therapy (SPT). Oral Health Prev. Dent. 2003, 1, 7–16. [Google Scholar]

- Pretty, I.A.; Ellwood, R.P.; Lo, E.C.; MacEntee, M.I.; Müller, F.; Rooney, E.; Thomson, W.M.; Van der Putten, G.J.; Ghezzi, E.M.; Walls, A.; et al. The Seattle Care Pathway for securing oral health in older patients. Gerodontology 2014, 31 (Suppl. 1), 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peres, M.A.; Macpherson, L.M.D.; Weyant, R.J.; Daly, B.; Venturelli, R.; Mathur, M.R.; Listl, S.; Celeste, R.K.; Guarnizo-Herreño, C.C.; Kearns, C.; et al. Oral diseases: A global public health challenge. Lancet 2019, 394, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borg-Bartolo, R.; Amberg, H.; Bieri, O.; Schirrmann, E.; Essig, S. The provision of mobile dental services to dependent elderly people in Switzerland. Gerodontology 2020, 37, 395–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Omran, M.O.; Livinski, A.A.; Kopycka-Kedzierawski, D.T.; Boroumand, S.; Williams, D.; Weatherspoon, D.J.; Iafolla, T.J.; Fontelo, P.; Dye, B.A. The use of teledentistry in facilitating oral health for older adults: A scoping review. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2021, 152, 998–1011.e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Tantawi, M.; Lam, W.Y.H.; Giraudeau, N.; Virtanen, J.I.; Matanhire, C.; Chifamba, T.; Sabbah, W.; Gomaa, N.; Al-Maweri, S.A.; Uribe, S.E.; et al. Teledentistry from research to practice: A tale of nineteen countries. Front. Oral Health 2023, 4, 1188557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, A.K.Y.; Tamrakar, M.; Leung, K.C.M.; Jiang, C.M.; Lo, E.C.M.; Chu, C.H. Oral Health Care of Older Adults in Hong Kong. Geriatrics 2021, 6, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neumann, D.G.; Quiñonez, C. A Comparative Analysis of Oral Health Care Systems in the United States, United Kingdom, France, Canada, and Brazil; Network for Canadian Oral Health Research Working Papers Series; Network for Canadian Oral Health Research: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2014; Volume 1, pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Watt, R.G.; Daly, B.; Allison, P.; Macpherson, L.M.D.; Venturelli, R.; Listl, S.; Weyant, R.J.; Mathur, M.R.; Guarnizo-Herreño, C.C.; Celeste, R.K.; et al. Ending the neglect of global oral health: Time for radical action. Lancet 2019, 394, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Integrated Care for Older People: Realigning Primary Health Care to Respond to Population Ageing. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/326295/WHO-HIS-SDS-2018.44-eng.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 8 March 2025).

| Active Agent | Antimicrobial Mechanisms | Delivery Format | Side Effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chlorhexidine gluconate |

|

|

|

| Stannous fluoride |

|

|

|

| Cetylpyridinium chloride |

|

|

|

| Essential oils |

|

| - |

| Step | Objective | Scopes of Work | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sort | To Reduce confusion |

|

| 2 | Set in order | To Keep tools more accessible |

|

| 3 | Shine | To Ensure hygiene and safety |

|

| 4 | Standardize | To Enhance adherence |

|

| 5 | Sustain | To Maintain long-term oral behavior change |

|

| Objectives | Scopes of Work |

|---|---|

| Periodontal Evaluation | |

|

|

| Risk factor control | |

|

|

| Oral Hygiene Instructions | |

|

|

| Professional mechanical plaque removal | |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chan, A.K.Y.; Tsang, Y.C.; Chu, S.; Chu, C.H. Comprehensive Strategies for Preventive Periodontal Care in Older Adults. Geriatrics 2025, 10, 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics10030072

Chan AKY, Tsang YC, Chu S, Chu CH. Comprehensive Strategies for Preventive Periodontal Care in Older Adults. Geriatrics. 2025; 10(3):72. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics10030072

Chicago/Turabian StyleChan, Alice Kit Ying, Yiu Cheung Tsang, Stephanie Chu, and Chun Hung Chu. 2025. "Comprehensive Strategies for Preventive Periodontal Care in Older Adults" Geriatrics 10, no. 3: 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics10030072

APA StyleChan, A. K. Y., Tsang, Y. C., Chu, S., & Chu, C. H. (2025). Comprehensive Strategies for Preventive Periodontal Care in Older Adults. Geriatrics, 10(3), 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics10030072