This study provided a scoping review of the published literature on viruses and their associated diseases in African ungulates. To our knowledge, it is the first of its kind on this topic, with the scientific community showing increased interest in this area.

Several recommendations are outlined below for future research opportunities based on the general characteristics of reported publications, viruses reported and diagnosed in African ungulates, specific ungulates affected by viruses, the geographical distribution of viruses and viruses that seem to be “under-studied”. The intention of this scoping review was to provide a foundation for more focused analyses to be performed in future research projects. This will allow current knowledge to be built upon and new knowledge bases to be developed.

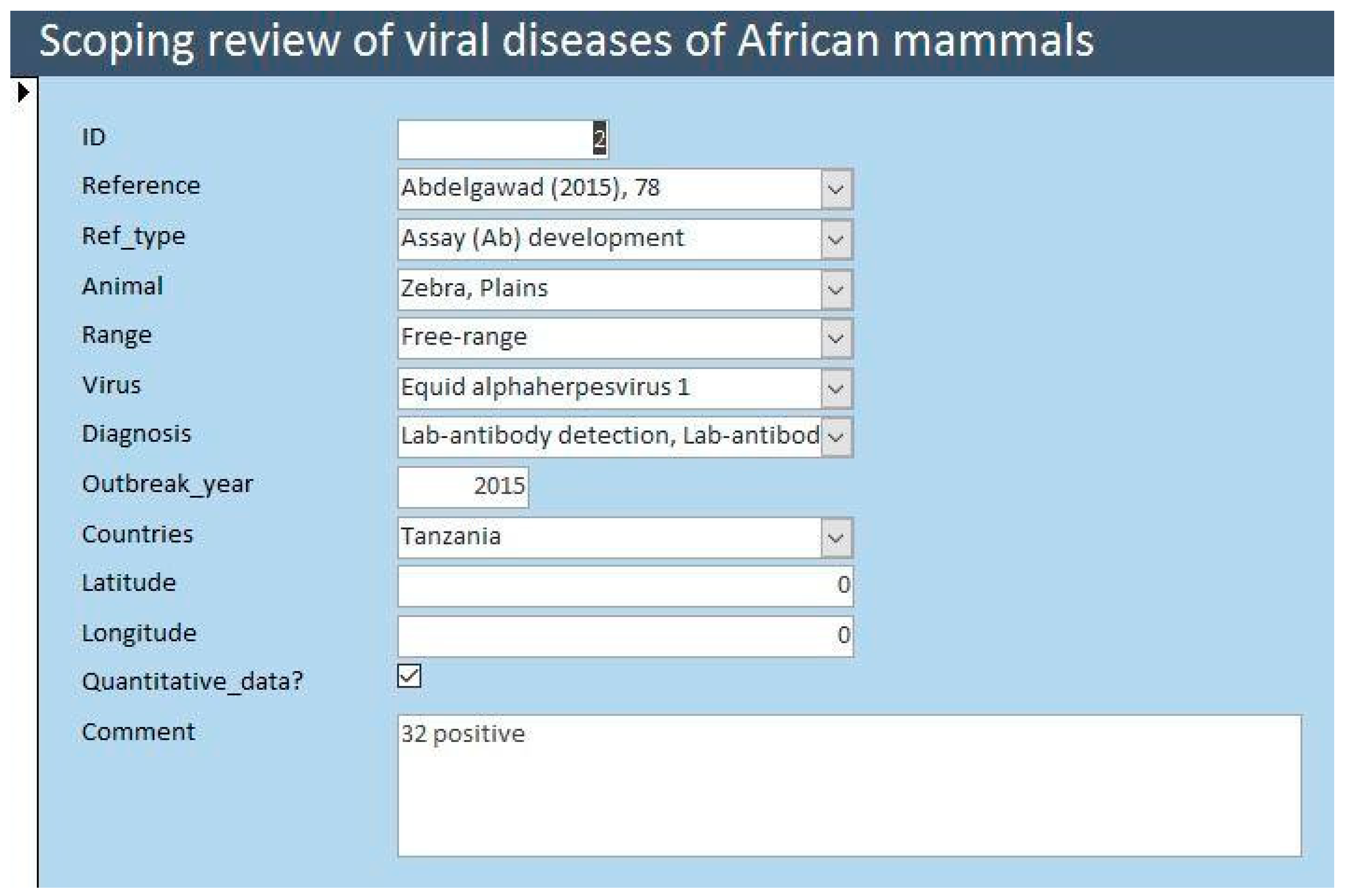

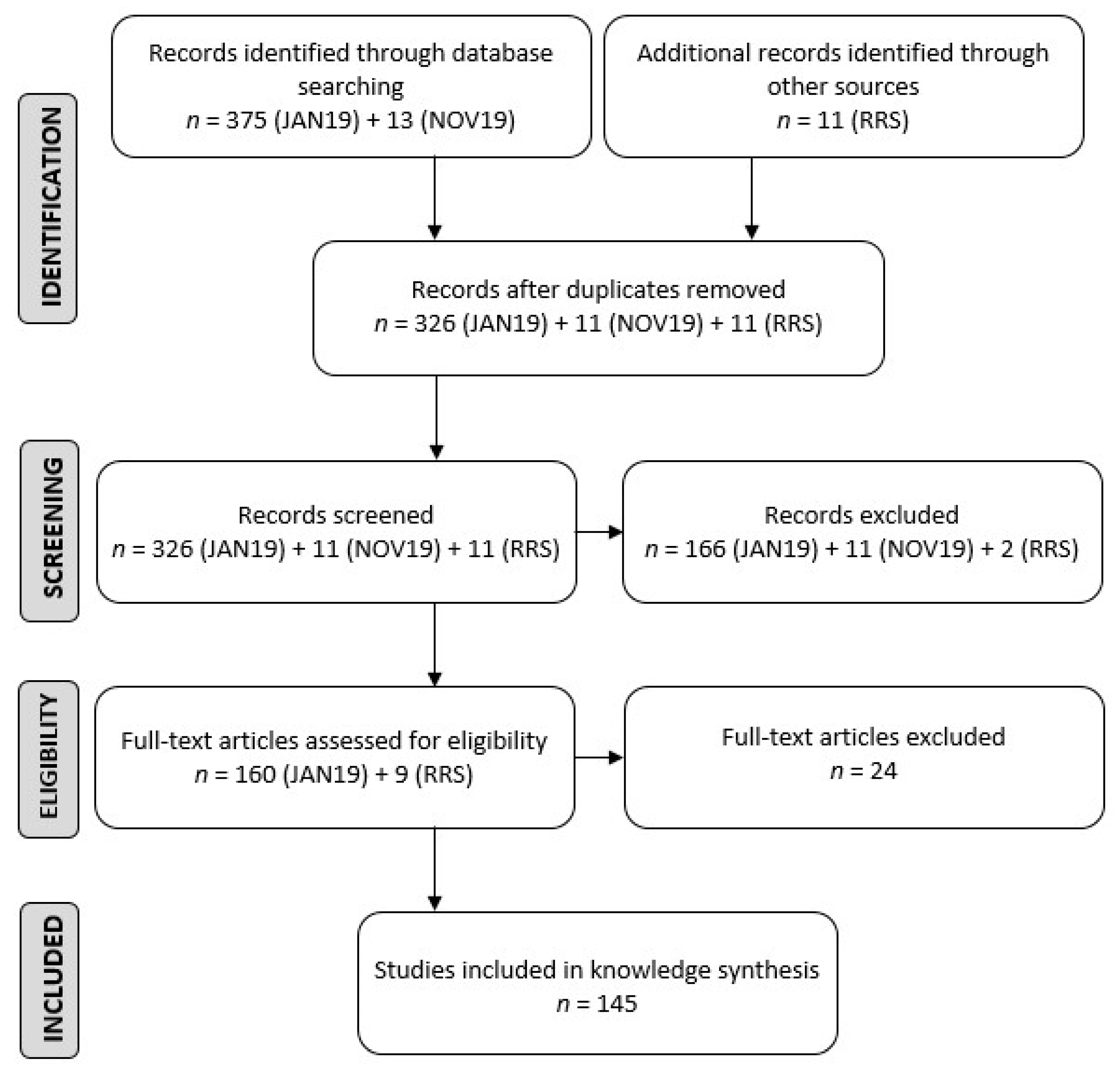

The search for publications to be included in this study was constructed so that it would be comprehensive but still practical as well as making efficient use of human and time resources. Publications reporting cases of viral disease or detection of viral antigens/antibodies or molecular viral isolation in African ungulates were relevant to this study. Consideration of the accuracy of the diagnosis made in the relevant publications broadly referring to viral disease in African ungulates was beyond the scope of this research study.

A number of publications were not detected during the search process by interrogating the database using the search string and were found via a reverse reference search process. The reason for publications not being detected during the search process was most likely due to the manner in which the databases’ search algorithms work. For example, the publications not initially detected may not have had specific words in their titles, abstracts or keyword lists or the correct combination of words between the three categories for the database algorithm to include the publications in the search results.

4.1.2. Viruses Reported and Diagnosed in African Ungulates

Based on the results, it has been established that many viruses can infect and, in some cases, cause disease in African ungulates. In addition, many of these viruses infect and cause disease in livestock too [

28] and it has been shown that the exposure of wildlife to domestic animals and/or human-generated activities, such as deforestation, urbanisation and agricultural intensification, play a major role as drivers for the emergence of wildlife diseases [

29].

The viruses of significance, according to the number of publications that have reported on them, are

Foot and mouth disease virus,

African swine fever virus,

Alcelaphine gammaherpesvirus 1 and

Rift Valley fever phlebovirus (

Table 2). These four viruses account for more than 50% (92/145) of the published research and reports on viral diseases in African ungulates. Based on the number of reports of viral antibody/antigen detected in African ungulates,

Foot and mouth disease virus,

Bovine alphaherpesvirus 2,

Alcelaphine gammaherpesvirus 1,

Pestivirus A/B,

Bluetongue virus,

Bovine alphaherpesvirus 1,

Bovine respirovirus 3,

African swine fever virus and

Rift Valley fever phlebovirus featured amongst the viruses most detected in African ungulates (

Table 3 and

Figure 3). This is likely because several of the publications involved viral antigen/antibody surveillance of large numbers of wild African ungulates.

Foot and mouth disease and African swine fever are two of the diseases of high interest due to their economic importance but neither are zoonotic [

30,

31]. Zoonotic viral diseases, such as Rift Valley fever and rabies, are of high importance because of the disease they cause in humans [

32,

33]. These diseases of high interest generally stimulate public and political interest and will automatically attract funding for research. In comparison, some viral diseases exclusive to animals which are listed as being diseases of high impact, e.g., African horse sickness and peste des petits ruminants, have significantly less research associated with them, likely due to the fact that they are of low economic, political and zoonotic interest within the context of African wildlife [

34,

35]. In addition, most of the other diseases which have high numbers of reports of being detected by antigen/antibody testing in African ungulates do not cause serious clinical disease in free-ranging wildlife, at least not that has been documented [

30,

33,

36,

37].

Foot and mouth disease virus has the largest number of publications reporting on it and has been detected the most by antigen/antibody testing in African ungulates compared to the other 31 viruses (

Table 3 and

Figure 3). It is a virus of significance based on research and its impact on the global economy, but it does not cause clinically significant disease in free-ranging African ungulates [

31]. It will only cause significant morbidity on occasion, specifically when the animals are stressed—for example, when animals are held in a boma facility for research purposes or relocation. A likely reason for foot and mouth disease receiving so much attention is that it is a highly trade-sensitive disease. This reflects the fact that funding into disease research is often driven by economic and political agendas [

31,

38]. In contrast, a virus such as rabies has a significantly smaller number of publications reporting on it in African ungulates despite causing widespread mortality and significant clinical disease, even in ungulates. Additionally, rabies is one of the most notable zoonotic diseases present and carries a significant threat to the health and conservation of wild carnivores [

32,

39,

40].

With African swine fever, years of funding and research have provided very limited effectiveness in reducing outbreaks of the disease and, at the time of writing, there were major outbreaks occurring across Europe and Asia, initiated and driven by increased and easier global travel, trade in pork (legal and illegal) and poor biosecurity measures, e.g., feeding of animal products to animals [

41]. Recently, there has been a change in research focus from wild suids to argasid ticks that are commonly found in warthog burrows and are responsible for the maintenance of

African swine fever virus and socioeconomic factors that drive the spread of the disease. This indicates that scientists are realising that these are the key issues requiring attention, rather than wild suids being the reservoir of African swine fever. For most viruses, the impact of infection, whether they cause clinical or subclinical infection in African ungulates, is limited [

42]. Transmission of African swine fever to domestic pigs at the wildlife/livestock interface in Africa is often suggested but a true interface is rarely documented [

41]. The spread of African swine fever to Europe and Asia was driven by trade in pork and poor biosecurity measures with minimal involvement of wild suids. However, African swine fever has now become well established in the wild boar population in parts of Europe, resulting in its spread across Europe [

41].

Alcelaphine gammaherpesvirus 1, causing malignant catarrhal fever, featured highly on the list of viruses when it came to the number of publications reporting on it and reports of its detection by antigen/antibody testing in African ungulates (

Table 3 and

Figure 3). This is interesting because, to date, very few clinical cases of malignant catarrhal fever have been reported in free-ranging African ungulates and a few cases have been reported in captive African buffalo [

43]. The reason for this finding is most likely due to the fact that malignant catarrhal fever is readily transmitted from blue and black wildebeest to cattle in conditions where they live in close proximity to each other [

43,

44]. This confirms that certain viruses are not of great significance in African wildlife but are of significance to livestock producers and hence will receive funding and interest from the agricultural sector. In addition, given that the only free-ranging African ungulate in which clinical disease of malignant catarrhal fever has been reported is the African buffalo, it is recommended that malignant catarrhal fever surveillance and research take place in buffalo in the future as it may be an emerging viral disease in this species or a reservoir species of

Alcelaphine gammaherpesvirus 1 may be identified from which spillover occurs to the buffalo [

43].

Rift Valley fever phlebovirus is a significant virus in the context of human, livestock and wildlife health; hence, it deserves to be listed as one of the viruses which had a high number of publications reporting on it and had a large number of reports of being detected by antigen/antibody testing in African ungulates (

Table 3 and

Figure 3). As an example, in 2010, there was an outbreak of Rift Valley fever in South Africa, with the first case being reported in January 2010 in the Free State province. By the end of the outbreak, the disease had been reported in eight of the nine provinces, KwaZulu-Natal being the only unaffected province [

45,

46]. It was also the first time in the history of Rift Valley fever outbreaks in South Africa that a winter rainfall area, i.e., the Western Cape, was affected [

46]. The government reported 237 confirmed human cases of Rift Valley fever, with 26 deaths and large numbers of animals affected, including sheep, goats, cattle and wildlife [

46,

47]. Based on this outbreak,

Rift Valley fever phlebovirus is evidently a pathogen of animal origin that has extended its host range and is able to infect humans. The outbreak seemed to be driven by climatic and ecological changes resulting in increased rainfall, as well as anthropogenic ecological changes (manmade dams and agricultural intensification) resulting in increased populations of mosquitoes. Despite ongoing research and the availability of vaccinations, this zoonotic disease, endemic to Africa’s tropical regions, is of significance as it has the potential to become a global emerging disease if a One Health management strategy is not implemented to manage it [

48,

49].

A noteworthy observation is that

Foot and mouth disease virus,

Bovine alphaherpesvirus 2,

Alcelaphine gammaherpesvirus 1,

Pestivirus A/B,

Bluetongue virus,

Bovine alphaherpesvirus 1,

Bovine respirovirus 3,

African swine fever virus and

Rift Valley fever phlebovirus are all viruses of great significance in domestic livestock agriculture, hence the reason for their surveillance in wildlife, but only a few of them cause significant clinical disease in free-ranging African ungulates. Additionally, there was some overlap but also some discrepancy between the number of publications reporting on viruses and the reports of viral antigen/antibody detected in African ungulates, i.e.,

African swine fever virus and

Rift Valley fever phlebovirus were lower on the ranking of viruses reported to be detected by antigen/antibody testing in African ungulates compared to the high ranking of viruses reported on by number of publications. A possible reason for this discrepancy with

African swine fever virus may be that the virus is very hard to detect in wild suids and a large number of publications focused on its detection in argasid ticks, which were outside the scope of this research study. Surveillance of

African swine fever virus in wild suids is very limited, resulting in a low ranking of viruses detected by viral antibody/antigen detection. In the case of

Rift Valley fever phlebovirus, the virus has a narrow region of infection, generally tropical areas with high rainfall, and has recently become an emerging disease and spread to new geographical areas. Surveillance for

Rift Valley fever phlebovirus has not been as significant as for some of the older viruses because it ranked lower on the list of viruses detected by viral antibody/antigen detection (

Table 3).

African elephant polyomavirus 1 is one of two viruses that was solely diagnosed in captive animals according to the published literature using antigen/antibody detection (

Figure 3). This is possibly because this is a new virus, diagnosed seven years ago, and there has not been much research published on it [

50]. The remainder of the viruses in

Figure 3 have either been diagnosed in a combination of free-ranging and captive animals, e.g.,

Foot and mouth disease virus,

African swine fever virus, or only in free-ranging ungulates, e.g.,

Akabane orthobunyavirus,

Bluetongue virus. It appeared that viruses that were diagnosed in both free-ranging and captive animals, e.g.,

Foot and mouth disease virus,

African swine fever virus, were the viruses that seemed to have the most publications reporting on them, likely because these viruses were the ones of major interest in the wildlife and livestock agricultural sectors. It is recommended that future research in this field be focused on

African elephant polyomavirus 1. However, currently, the virus does not seem to bear severe consequences or risks for the health of free-ranging elephants; therefore, passive or low-grade active surveillance can be performed in addition to other diseases being researched/surveyed to maximise resource use. An additional recommendation is to perform research dedicated to investigating

Akabane orthobunyavirus and its relationship with black and white rhinoceros as it may be of interest to the conservation of these endangered species.

4.1.5. Viruses which Seem to Be “Under-Studied”

Several of the 32 viruses reported to infect African ungulates are classified as high-impact viruses because they have a significant negative impact on the health and lives of animals and humans [

10,

25] and are listed as notifiable diseases to the OIE [

26]. The high-impact viral diseases diagnosed in African ungulates that are of significance in the African context are as follows:

Interestingly, a virus species that affects a wide range of African ungulates does not necessarily classify that particular virus as high-impact. For example, of the top five virus species affecting the widest ranges of African ungulates, Foot and mouth disease virus, Pestivirus A/B and Bovine alphaherpesvirus 1 represent some of the high-impact viruses and only Foot and mouth disease virus is of significance in the African context.

Certain diseases, such as peste des petits ruminants, which can have a significant impact on wildlife, do not seem to receive as much attention as they should. It would be helpful to have a “Wildlife disease and infection” category, similar to the other categories on the list, added to OIE-listed diseases. For example, Rift Valley fever and infection with

Elephant polyomavirus 1 could be listed under the new category. This is an important consideration, especially to allow future conservation efforts and campaigns to take diseases into account, as infectious diseases are becoming more prevalent in wildlife populations with the intensification of agriculture and the increased amount of wildlife/livestock/human interactions [

3]. The OIE-listed diseases pertain to the World Trade Organisation; if certain diseases are threatening the conservation and/or associated economy of a wildlife species, then, ideally, trade that may spread that disease should be halted.

A clear knowledge gap is highlighted in research focusing on Lumpy skin disease virus, Small ruminant morbillivirus and African horse sickness virus. The reason for the under-reporting of research on these three diseases may be due to the difficulty of testing and surveillance for disease in free-ranging African ungulates. For example, game rangers may come across a dead animal and if the carcass is fresh, samples may be collected. However, synthesising a case report from limited information is particularly challenging and unlikely to be published in a peer-reviewed scientific journal unless it is of great significance. Another reason for which these diseases may be under-reported is that lumpy skin disease and African horse sickness do not cause significant clinical disease in African ungulates. In addition, disease research focuses mainly on livestock, instead of wildlife, because agriculture and food production play a major role in the economies of countries across the globe. Therefore, many publications discussing diseases in wildlife is due to the disease being important in livestock. A good example of this is foot and mouth disease, which is a very important disease in livestock but much less so in wildlife. Nevertheless, these diseases are of great significance in the context of livestock health and, given that African ungulates may play a role in the epidemiology of these diseases, it is important that these diseases are strongly considered as research topics in the future.