Pet Ownership and Quality of Life: A Systematic Review of the Literature

Abstract

:1. Introduction

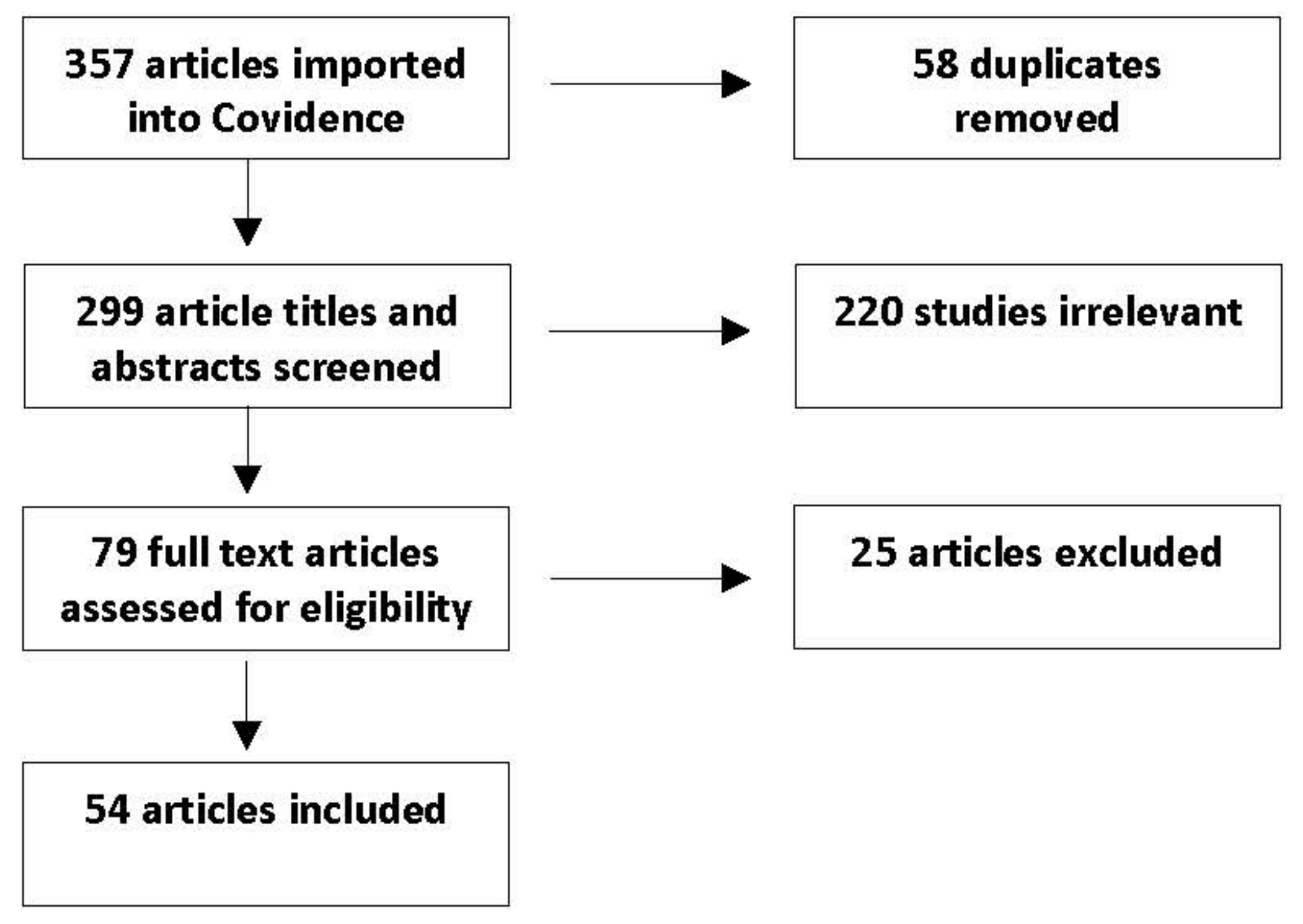

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Article Quality Index | |

| 1 | Was the study purpose reported? 1 = yes, 0 = no |

| 2 | Did the study design include a comparison group? 1 = yes, 0 = no |

| 3 | Was the recruitment method reported? 1 = yes, 0 = no |

| 4 | Was the sample size response rate over 50%? 1 = yes, 0 = no (or unreported) |

| 5 | Were sample demographics reported? (3 or more demographic categories reported)1 = yes, 0 = no |

| 6 | Was the sample representative (not self-selected)? 1 = yes, 0 = no (or not reported) |

| 7 | Did mental health diagnosis occur through standardized scale or mental health professionals? 1 = yes, 0 = no |

| 8 | Was the validity and/or reliability of scales reported? 1 = yes, 0 = no |

| 9 | Was there a study limitation section? 1 = yes, 0 = no |

Appendix B

| Author | Title | Year | Sample Size | Methods | Sample Population | Mental Health Measurement(s) | Findings | Article Quality Index Score (0–9) |

| Research with Positive Associations between Pet Ownership and Mental Health | ||||||||

| Serpell, J. [43] | Beneficial effects of pet ownership on some aspects of human health and behaviour | 1991 | 71 | -Prospective -Quantitative | General | -GHQ-30 | After acquiring a pet, dog-owners demonstrated significant improvement in their GHQ-30 scores during the first six months after acquiring a pet, and moderate at 10-month follow-up. Cat owners demonstrated small and non-statistically significant improvement at six months. | 3 |

| Budge, R.C. et al. [48] | Health correlates of compatibility and attachment in human-companion animal relationships | 1998 | 176 | -Cross-sectional -Quantitative | General | -AHCS -Pet Attachment Survey -ISEL -MHI | As compatibility in the human–pet relationship increased, so did the physical and mental health and wellbeing for the human. Human–pet compatibility was not associated with levels of social support. | 5 |

| Zimolag, U.; Krupa, T. [49] | Pet Ownership as a Meaningful Community Occupation for People With Serious Mental Illness | 2009 | 59 | -Cross-sectional -Quantitative | People receiving mental illness treatment | -GAF -EMAS -CIS-APP | Pet owners demonstrated better social community integration than non-pet owners. Pet owners may also engage in more meaningful activity and have higher psychological community integration than non-pet owners. | 6 |

| McConnell, A.R. et al. [50] | Friends with benefits: on the positive consequences of pet ownership | 2011 | 217 | Prospective, cross section -Quantitative | General | -CES-D -UCLA -RSES -SHS | Pets can serve as effective social resources for their owners and positive connections with pets are correlated with positive attachment styles, personality traits, and self-esteem generally and when facing social rejection. | 4 |

| Black, K. [51] | The Relationship Between Companion Animals and Loneliness Among Rural Adolescents | 2012 | 293 | -Cross-sectional -Quantitative | Adolescents | -ULS -CABS -SSQSR | Pet owning adolescents had significantly lower loneliness scores and there was an inverse relationship between level of bond with pet and levels of loneliness. | 8 |

| Stern, S.L. et al. [52] | Potential Benefits of Canine Companionship for Military Veterans with Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) | 2013 | 30 | -Cross-sectional -Quantitative | Military Veterans | -BDI -LAPS -PCL | Since adopting their dog, veterans self-reported feeling calmer, less lonely, less depressed, and less worried about their and their family’s safety. Veterans did not report less PTSD symptomatology since adopting their dog. | 6 |

| Wright, H. et al. [53] | Pet Dogs Improve Family Functioning and Reduce Anxiety in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder | 2015 | 70 | -Cross-sectional -Quantitative | Children with ASD and their families | -BFRS -SCAS | Family functioning improved and child anxiety decreased in the dog-owning group compared to the non-dog owning group. | 6 |

| Gadomski, A.M. et al. [54] | Pet Dogs and Children’s Health: Opportunities for Chronic Disease Prevention? | 2015 | 643 | -Cross-sectional -Quantitative | Children | -SCARED-5 -SDQ -PHQ-2 | Having a pet dog in the home was associated with a decreased probability of childhood anxiety. | 5 |

| Lem, M.; Coe et al. [55] | The Protective Association between Pet Ownership and Depression among Street-involved Youth: A Cross-sectional Study | 2016 | 190 | -Cross-sectional -Quantitative | Children and adolescents | -CES-D | Pet ownership among street youth was associated with lower levels of depression. | 7 |

| Bos, E.H. et al. [29] | Preserving Subjective Wellbeing in the Face of Psychopathology: Buffering Effects of Personal Strengths and Resources | 2016 | 2411 | -Cross-sectional -Quantitative | General | -MANSA -HI -PWB -SPF-IL -DASS -QIDS -PANAS -HSQ -EQ | Owning a pet and/or having a partner protected study participants’ wellbeing even when psychological distress symptoms were present. | 6 |

| Hall, S.S. et al. [56] | The long-term benefits of dog ownership in families with children with autism | 2016 | 37 | -Longitudinal -Mixed | Children with ASD and their families | -PSI-SF -LAPS | Families of autistic children who had acquired a pet dog demonstrated improved family functioning and reduced parental stress in comparison to control group families who did not acquire a pet dog. | 8 |

| Marsa-Sambola, F. et al. [57] | Quality of life and adolescents’ communication with their significant others (mother, father, and best friend): the mediating effect of attachment to pets | 2017 | 2262 | -Cross-sectional -Quantitative | Adolescents | -KIDSCREEN-10 Index -SAPS | Higher attachment to pet dog/cat was associated with better quality of life. Attachment to pets may also enhance communication with parents and best friends. | 6 |

| Muldoon, A.L. et al. [58] | A Web-Based Study of Dog Ownership and Depression Among People Living With HIV | 2017 | 199 | -Cross-sectional -Quantitative | People with a physical illness | -CES-D10 -RRC-ARM -CYRM-28 | Non-current dog ownership among research participants was significantly and positively associated with depression with non-current dog owners being three times more likely to report symptoms of depression compared with current dog owners. | 8 |

| Wu, C.S.T. et al. [59] | The Association of Pet Ownership and Attachment with Perceived Stress among Chinese Adults | 2018 | 288 | -Cross-sectional -Quantitative | General | -PSS -CABS | Higher levels of pet attachment are associated with lower levels of perceived stress among pet owners. Dog owners report being more attached to their pet than other types of pet owners. | 7 |

| Powell, L. et al. [60] | Companion dog acquisition and mental well-being: a community-based three-arm controlled study | 2019 | 71 | -Prospective -Quantitative | General | -ULS -PANAS -K-10 | Acquiring a dog was associated with lower levels of loneliness at three-month and eight-month follow up. | 6 |

| Carr, E.C.J. et al. [61] | Evaluating the Relationship between Well-Being and Living with a Dog for People with Chronic Low Back Pain: A Feasibility Study | 2019 | 56 | -Cross-sectional -Mixed methods | People with a physical illness | -HRQOL -WHO-5 -PROMIS anxiety SF4 -PROMIS depression SF4 -ULS -SSNS -PROMIS Companionship scale -PROMIS Emotional support scale -LAPS -HAB | Dog owners reported fewer depression and anxiety symptoms over the last week before the survey than the non-dog owners. | 5 |

| Yolken, R. et al. [28] | Exposure to household pet cats and dogs in childhood and risk of subsequent diagnosis of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder | 2019 | 1371 | -Cross-sectional -Qualitative | People receiving mental illness treatment | N/A | Exposure to a pet dog during the first 12 years of life was associated with a decreased hazard of having a subsequent diagnosis of schizophrenia. | 5 |

| Research with Mixed Associations between Pet Ownership and Mental Health | ||||||||

| Siegel, J.M. [62] | Stressful life events and use of physician services among the elderly: the moderating role of pet ownership | 1990 | 938 | -Prospective -Mixed | Elderly | -LNS -CES-D | Elderly respondents with stressful life events made fewer visits to the physician if they had a pet dog. The presence of a dog was not associated with lower levels of depression. | 6 |

| Gulick, E.E.; Krause-Parello, C. A. [63] | Factors related to type of companion pet owned by older women | 2012 | 159 | -Cross-sectional -Quantitative | Elderly (females) | -PGWB -ULS | Women with dogs reported higher general health, vitality, and total well-being but worse levels of depression than women with cats. | 6 |

| Fritz, C.L. et al. [64] | Companion animals and the psychological health of Alzheimer patients’ caregivers | 1996 | 244 | -Cross-sectional -Quantitative | Caregivers | -ZBI -LSI-Z -GDS -LAPS | Stress was less for pet owning younger male and female caregivers of cognitively impaired adults but not for older pet owning female caregivers. | 5 |

| Tower, R.B.; Nokota, M. [19] | Pet companionship and depression: results from a United States Internet sample | 2006 | 2291 | -Cross-sectional -Quantitative | General | -CES-D | Unmarried women who live with a pet had the fewest depressive symptoms and unmarried men who live with a pet had the most. | 6 |

| Wisdom, J.P.; Saedi, G.A.; Green, C.A. [38] | Another Breed of “Service” Animals: STARS Study Findings About Pet Ownership and Recovery From Serious Mental Illness | 2009 | 177 | Prospective -Longitudinal -Mixed Methods | People with serious mental illness | -CSI -W-QLI | Pet owners were more likely to have affective versus psychotic diagnosis, were more likely to have a comorbid substance abuse disorder and were more likely to live with someone. They also had fewer hospitalizations. | 4 |

| Cline, K.M.C. [65] | Psychological Effects of Dog Ownership: Role Strain, Role Enhancement, and Depression | 2010 | 201 | -Cross-sectional -Quantitative | General | -CES-D | Dog ownership had no direct impact on depression. Dog ownership was associated with greater wellbeing for women and those who are unmarried. | 7 |

| Ramirez, M.T.G.; Hernandez, R.L. [66] | Benefits of dog ownership: Comparative study of equivalent samples | 2014 | 602 | Prospective- Cross-Sectional -Quantitative (Snowball sampling) | General | -SWLS -SHS -PHQ -PSS -SFHS | Dog owners’ scores were significantly lower for psychosomatic symptoms and stress and were higher for better mental health, however, there were no differences between groups for happiness and life satisfaction. | 5 |

| Bradley, L.; Bennett, P.C. [22] | Companion-Animals’ Effectiveness in Managing Chronic Pain in Adult Community Members | 2015 | 173 | -Cross-sectional -Mixed methods | People with physical illness | -DASS-21 | There was no relationship between companion animal ownership and stress or anxiety, however, owners had higher levels of depression than non-owners. Depression among those who perceived their animal as more friendly was lower and for those who perceived their animal as more disobedient stress was higher. | 5 |

| Girardi, A.; Pozzulo, J.D. [24] | Childhood Experiences with Family Pets and Internalizing Symptoms in Early Adulthood | 2015 | 318 | -Cross-sectional -Quantitative | General | -LAPS -CTQ -CEDV -STAI-T -BDI | Participants who were exposed to pet aggression in childhood and reported medium level bonds with animals also reported more depression and anxiety symptoms in early adulthood. Those who were not exposed to pet aggression reported fewer internalizing symptoms. | 7 |

| Bennett, P.C. et al. [67] | An Experience Sampling Approach to Investigating Associations between Pet Presence and Indicators of Psychological Wellbeing and Mood in Older Australians | 2015 | 68 | -Prospective Experience sampling over 7 days -Quantitative | Elderly | -DASS -SPS -ULS-R | There was not a difference between pet-owners and non-pet-owners in mental health outcomes, however, for pet owners, level of pet presence in daily activities was associated with better mental health outcomes. | 6 |

| Branson, S.M. et al [68]. | Depression, loneliness, and pet attachment in homebound older adult cat and dog owners | 2017 | 39 | -Cross-sectional -Quantitative | Elderly | -GDS-SF -ULS-R | Cat owners reported fewer depressive symptoms than dog owners, especially for men, but the differences in levels of depressive symptoms between dog and cat owners was small. | 6 |

| Mueller, M.K. et al. [69] | Human-animal interaction as a social determinant of health: descriptive findings from the health and retirement study | 2018 | 1657 | -Retrospective -Cross-sectional -Quantitative | Elderly | - Created measures | Pet ownership was positively correlated with reporting depression in lifetime, however, there was no difference in self-reported depression in the last week between pet owners and non-owners. | 6 |

| Carr, D.C. et al. [70] | Typologies of older adult companion animal owners and non-owners: moving beyond the dichotomy | 2019 | 1179 | -Cross-sectional -Quantitative Data was collected from the Health a Retirement Study | Elderly | -CES-D -BFI | Five clusters of owners and four clusters of non-owners were identified with varying mental health outcomes. Pet owners were higher in neuroticism and lower in extraversion. | 5 |

| Liu, S.X. et al. [30] | Is Dog Ownership Associated with Mental Health? A Population Study of 68,362 Adults Living in England | 2019 | 68,362 | -Repeated cross-sectional survey running in annual thematic cycles -Quantitative | General | -GHQ-12 | Single dog owners were more likely to demonstrate higher levels of short-term psychological distress. Dog owners with partners had lower levels of self-reported mental illness. | 7 |

| Ingram, K.M.; Cohen-Filipic, J. [20] | Benefits, challenges, and needs of people living with cancer and their companion dogs: An exploratory study | 2019 | 122 | -Cross-sectional -Mixed methods | People with physical illness | -CES-D -FACT-G -LAPS | The human–pet bond was not directly linked with well-being. Depressive symptoms depended on cancer treatment status and level of bond with those having completed treatment and had a stronger bond reported fewer depressive symptoms. For continuing treatment stronger bonds was positively correlated with depression. | 5 |

| Min, K.D. et al. [71] | Owners’ Attitudes toward Their Companion Dogs Are Associated with the Owners’ Depression Symptoms-An Exploratory Study in South Korea | 2019 | 654 | -Cross-sectional -Quantitative | General | -CES-D | Those respondents who had a negative view of their pets also were more likely to report the presence of depression. Those who had a more positive view of their pet were less likely to report depression. | 5 |

| Hajek, A.; Konig, H.H. [23] | How do cat owners, dog owners and individuals without pets differ in terms of psychosocial outcomes among individuals in old age without a partner? | 2020 | 1160 | -Longitudinal -Cross-sectional -Quantitative | Elderly | -CES-D -De Jong Gierveld Loneliness Scale | Dog owners were less socially isolated than non-pet owners, however this was not true for cat owners. Pet-owning women also reported less loneliness, whereas loneliness did not differ between pet-owning and non-pet-owning men. | 8 |

| Teo, J.T.; Thomas, S. J. [72] | Psychological Mechanisms Predicting Wellbeing in Pet Owners: Rogers’ Core Conditions versus Bowlby’s Attachment | 2019 | 298 | -Cross-sectional -Quantitative | General | -DASS-21 -BSI -WHO QOLBREF -OPRQ -PAQ -BLRI | Pet owners and non-pet owners did not significantly differ in terms of QOL or psychopathology. However, in pet owners, secure pet attachments were associated with lower psychological distress and psychopathology. Differences in wellbeing is related to qualities of individual human–pet relationships. | 7 |

| Endo, K. et al. [73] | Dog and Cat Ownership Predicts Adolescents’ Mental Well-Being: A Population-Based Longitudinal Study | 2020 | 2584 | -Prospective cohort study -Quantitative and qualitative | Adolescents | -WHO-5 | Dog ownership at age 10 predicted better well-being at age 12 compared to no dog ownership. Cat ownership at age 10 predicted worse well-being at age 12 compared to no cat ownership. | 4 |

| Research with Negative Associations between Pet Ownership and Mental Health | ||||||||

| Parslow, R.A. et al. [74] | Pet ownership and health in older adults: Findings from a survey of 2551 community-based Australians aged 60–64 | 2005 | 2551 | -Cross-sectional -Quantitative | Elderly | -SF-12 -GADS -PANAS -EPQ-R | Those with pets have poorer mental and physical health and use more pain relief medication than those without pets. Further, our study suggests that those with pets are less conforming to social norms as indicated by their higher levels of psychoticism. | 6 |

| Mullersdorf, M. et al. [40] | Aspects of health, physical/leisure activities, work and socio-demographics associated with pet ownership in Sweden | 2010 | 39,995 | Retrospective- Cross-sectional -Quantitative | General | -Aspects of health and mental health on a five-point Likert scale | “Pet owners in this study reported poorer mental health than non-pet owners. However, the authors suggest that the increase in depression or feelings of loneliness might predispose people to buying a pet.” | 7 |

| Antonacopoulos, N.M.D.; Pychyl, T.A. [13] | An Examination of the Potential Role of Pet Ownership, Human Social Support and Pet Attachment in the Psychological Health of Individuals Living Alone | 2010 | 132 | -Cross-sectional -Mixed Methods | General (adults living alone) | -MSPSS -LAPS -CES-D -ULS | “High attachment to pets predicted significantly higher scores on loneliness and depression. Our findings emphasize the complexity of the relationship between pet ownership and psychological health and suggest that pet ownership may not be beneficial for the psychological health of all individuals living alone.” | 7 |

| Peacock, J. et al. [12] | Mental health implications of human attachment to companion animals | 2012 | 150 | -Cross-sectional -Quantitative | General | -BSI-18 -MDSS -CEN SHARE PAS -OPRQ | “Human–animal relationships are associated with increased reports of psychological symptomatology. This study adds to the body of evidence that suggests that to understand human-animal relationships and their impact on well-being, it is pivotal to assess what the relationship symbolizes for an individual.” | 6 |

| Sharpley, C.et al. [75] | Pet ownership and symptoms of depression: A prospective study of older adults | 2019 | 5334 | -Longitudinal -Cross-sectional -Quantitative | Elderly | -CES-D | “In conclusion, the present results indicate that an increase in depressive symptoms is associated with higher odds of dog ownership in community-dwelling older people, but provide no evidence of a protective effect of pet ownership on changes in depressive symptoms over time.” | 6 |

| Research with No Associations between Pet Ownership and Mental Health | ||||||||

| Raina, P. et al. [76] | Influence of companion animals on the physical and psychological health of older people: an analysis of a one-year longitudinal study | 1999 | 995 | -Longitudinal -Cross-Sectional | Elderly | -LAPS -Reported levels of satisfaction regarding mental health, happiness, and relationships | “No statistically significant direct association was observed between pet ownership and change in psychological wellbeing However, pet ownership significantly modified the relationship between social support and the change in psychological well-being over a 1-year period.” | 4 |

| El-Alayli, A. et al. [77] | Reigning cats and dogs: A pet-enhancement bias and its link to pet attachment, pet-self similarity, self-enhancement, and well-being | 2006 | 70 | Prospective -Quantitative | General | -PAS -CABS -SWLS -PANAS -SHS | “A secondary objective of this research was to examine whether psychological well-being was related to pet enhancement, pet attachment, and pet–self similarity. We found no evidence suggesting a linear relationship between pet attachment and psychological well-being.” | 6 |

| Wells, D.L. [78] | Associations between pet ownership and self-reported health status in people suffering from chronic fatigue syndrome | 2009 | 193 | Cross-sectional | People with physical illness | -GHQ-12 -SF36 | Overall, findings suggest no statistically significant association between pet ownership and self-reported health in people with CFS. Nonetheless, people suffering from this condition believe that their pets have the potential to enhance quality of life. | 6 |

| Nagasawa, M.; Ohta, M [79]. | The influence of dog ownership in childhood on the sociality of elderly Japanese men | 2010 | 220 | -Cross-sectional -Quantitative | Elderly | -IKIGAI -ULS-R -JMS-SSS | The effect of dog ownership on the mental condition of an elderly Japanese male may or may not be related to the early childhood dog ownership. | 6 |

| Rijken, M.; Van Beek, S. [80] | About Cats and Dogs Reconsidering the Relationship Between Pet Ownership and Health Related Outcomes in Community-Dwelling Elderly | 2011 | 1410 | -Prospective -Cross-sectional -Quantitative | Elderly | -GHQ-12 -ULS | Associations between pet ownership and the frequency of social contacts or feelings of loneliness were not found. Having a dog increased the likelihood of being healthy/active, whereas having a cat showed the opposite. | 8 |

| Ramirez, M.T.G., et al. [66] | Benefits of dog ownership: Comparative study of equivalent samples | 2014 | 602 | -Prospective survey -Quantitative | general | -SWLS -SHS -PHQ -PSS -SF-36 | Dog owners had lower stress than non-dog owners, but there was no difference in overall mental health or happiness. | 5 |

| Enmarker, I. et al. [81] | Depression in older cat and dog owners: the Nord-Trondelag Health Study (HUNT)-3 | 2015 | 12,093 | -Cross-sectional -Mixed methods | Elderly | -HADS-d | When comparing pet owners and non-pet owners, self-reported symptoms of depression in older women do not change based on ownership. | 7 |

| Bao, K.J.; Schreer, G. [82] | Pets and Happiness: Examining the Association between Pet Ownership and Wellbeing | 2016 | 262 | -Cross-sectional -Quantitative | general | -SHS -SWLS -mDES -ERQ -BMPN -BFI | Participants who owned pets and those who did not own pets did not appear to be very different in terms of wellbeing, personality, happiness, positive emotions, or negative emotions. Dog owners were happier than cat owners. | 7 |

| Miles, J.N.V. et al. [83] | A Propensity-Score-Weighted Population-Based Study of the Health Benefits of Dogs and Cats for Children | 2017 | 5191 | -Retrospective -Cross-sectional | Children | -GHQ-12 -SF-36 | When variables related to child development were controlled for, there was no evidence of a positive impact of pet ownership on child mental health. | 4 |

| Batty, G.D. et al. [84] | Associations of pet ownership with biomarkers of ageing: population based cohort study | 2017 | 8785 | -Prospective -Quantitative | Elderly | -CES-D | There was no evidence of a clear association of any type of pet ownership with depressive symptoms | 6 |

| Dunn, S.L. et al. [85] | Dog Ownership and Dog Walking The Relationship With Exercise, Depression, and Hopelessness in Patients With lschemic Heart Disease | 2018 | 122 | -Prospective -Quantitative | Physical illness | -PHQ-9 -STHS | No differences in levels of hopelessness between the groups. Dog owners were more depressed until adjusting for age and sex, then no significant differences between dog owners and non-dog owners. | 8 |

| Zijlema, W.L. et al. [86] | Dog ownership, the natural outdoor environment and health: a cross-sectional study | 2019 | 3586 | -Cross-sectional -Quantitative | General | -SF-36 | There was no indication for an association between dog ownership and mental health in groups with high or low access to natural outdoor environment (NOE) and with high or low residential surrounding greenness on the whole. | 6 |

| Branson, S.M. et al. [87] | Biopsychosocial Factors and Cognitive Function in Cat Ownership and Attachment in Community-dwelling Older Adults | 2019 | 96 | -Cross-sectional -Quantitative | Elderly | -LAPS -PSS -ULS -GDS-SF -Stress Salivary Biomarker | No associations with the biopsychosocial and cognitive measures. No link between the level of pet attachment and loneliness and depression. | 7 |

References

- American Pet Products Association. 2019–2020 APPA National Pet Owners Survey; American Pet Products Association: Stamford, CT, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, F. Human-animal bonds II: The role of pets in family systems and family therapy. Fam. Process. 2009, 48, 481–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassels, M.T.; White, N.; Gee, N.; Hughes, C. One of the family? Measuring young adolescents’ relationships with pets and siblings. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2017, 49, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedmann, E.; Thomas, S.A. Health benefits of pets for families. In Pets and the Family; Sussman, M.B., Ed.; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 1985; pp. 191–204. [Google Scholar]

- Wollrab, T.I. Human-animal bond issues. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 1998, 212, 1675. [Google Scholar]

- Friedmann, E.; Son, H. The human-companion animal bond: How humans benefit. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Small Anim. Pract. 2009, 39, 293–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, E.K.; Worsham, N.L.; Swinehart, E.R. Benefits derived from companion animals, and the use of the term “attachment”. Anthrozoös 2006, 19, 98–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodsworth, W.; Coleman, G.J. Child-companion animal attachment bonds in single and two-parent families. Anthrozoös 2001, 14, 216–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westgarth, C.; Christley, R.M.; Marvin, G.; Perkins, E.I. Walk my dog because it makes me happy: A qualitative study to understand why dogs motivate walking and improved health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Carr, E.C.J.; Wallace, J.E.; Onyewuchi, C.; Hellyer, P.W.; Kogan, L. Exploring the meaning and experience of chronic pain with people who live with a dog: A qualitative study. Anthrozoös 2018, 31, 551–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, D.L. The effects of animals on human health and well-being. J. Soc. Issues 2009, 65, 523–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peacock, J.; Chur-Hansen, A.; Winefield, H. Mental health implications of human attachment to companion animals. J. Clin. Psychol. 2012, 68, 292–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonacopoulos, N.M.D.; Pychyl, T.A. An examination of the potential role of pet ownership, human social support and pet attachment in the psychological health of individuals living alone. Anthrozoös 2010, 23, 37–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hepper, P.G.; Wells, D.L. Pet ownership and adults’ views on the use of animals. Soc. Anim. 1997, 5, 45–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzog, H. The impact of pets on human health and psychological well-being: Fact, fiction, or hypothesis? Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2011, 20, 236–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, A.; Towell, T. Cat and dog companionship and well-being: A systematic review. Int. J. Appl. Psychol. 2013, 3, 149–155. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, H.L.; Rushton, K.; Lovell, K.; Bee, P.; Walker, L.; Grant, L.; Rogers, A. The power of support from companion animals for people living with mental health problems: A systematic review and narrative synthesis of the evidence. BMC Psychiatry 2018, 18, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Platt, B.; Hawton, K.; Simkin, S.; Mellanby, R.J. Suicidal behaviour and psychosocial problems in veterinary surgeons: A systematic review. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2012, 47, 223–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tower, R.B.; Nokota, M. Pet companionship and depression: Results from a United States internet sample. Anthrozoös 2006, 19, 50–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingram, K.M.; Cohen-Filipic, J. Benefits, challenges, and needs of people living with cancer and their companion dogs: An exploratory study. J. Psychosoc. Oncol. 2019, 37, 110–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, C.L.; Farver, T.B.; Hart, L.A.; Kass, P.H. Companion animals and the psychological health of Alzheimer patients’ caregivers. Psychol. Rep. 1996, 78, 467–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradley, L.; Bennett, P.C. Companion-animals’ effectiveness in managing chronic pain in adult community members. Anthrozoös 2015, 28, 635–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajek, A.; König, H.-H. How do cat owners, dog owners and individuals without pets differ in terms of psychosocial outcomes among individuals in old age without a partner? Aging Ment. Health 2020, 24, 1613–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Girardi, A.; Pozzulo, J.D. Childhood experiences with family pets and internalizing symptoms in early adulthood. Anthrozoös 2015, 28, 421–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deas, G.W. Keeping mamma around: House calls. New York Amsterdam News (1962–1993), 9 May 1992; 14–16. [Google Scholar]

- Behravesh, C.B. Power of the Pet: Pets Enrich Our Lives. Available online: https://www.huffpost.com/entry/power-of-the-pet-pets-enrich-our-lives_b_5908a7abe4b084f59b49fcf4 (accessed on 7 December 2021).

- Reigning Cats and Dogs. 2019. Available online: https://www.economist.com/leaders/2019/06/22/pets-have-gained-the-upper-paw-over-their-so-called-owners (accessed on 7 December 2021).

- Yolken, R.; Stallings, C.; Origoni, A.; Katsafanas, E.; Sweeney, K.; Squire, A.; Dickerson, F. Exposure to household pet cats and dogs in childhood and risk of subsequent diagnosis of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0225320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bos, E.H.; Snippe, E.; de Jonge, P.; Jeronimus, B. Preserving subjective wellbeing in the face of psychopathology: Buffering effects of personal strengths and resources. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0150867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Powell, L.; Chia, D.; Russ, T.C.; McGreevy, P.D.; Bauman, A.E.; Edwards, K.M.; Stamatakis, E. Is dog ownership as-sociated with mental health? A population study of 68,362 adults living in England. Anthrozoös 2019, 32, 729–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strand, E.B.; Faver, C.A. Battered women’s concern for their pets: A closer look. J. Fam. Soc. Work 2005, 9, 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, H.; Rushton, K.; Walker, S.; Lovell, K.; Rogers, A. Ontological security and connectivity provided by pets: A study in the self-management of the everyday lives of people diagnosed with a long-term mental health condition. BMC Psychiatry 2016, 16, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Katz, J. The New Work of Dogs: Tending to Life, Love, and Family; Random House Trade Paperbacks: New York, NY, USA, 2004; p. 272. [Google Scholar]

- Serpell, J. How happy is your pet? The Problem of subjectivity in the assessment of companion animal welfare. Anim. Welf. 2019, 28, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundman, A.-S.; Van Poucke, E.; Holm, A.-C.S.; Faresjö, Å.; Theodorsson, E.; Jensen, P.; Roth, L.S.V. Long-term stress levels are synchronized in dogs and their owners. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 7391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Morgan, L.; Protopopova, A.; Birkler, R.I.D.; Itin-Shwartz, B.; Sutton, G.A.; Gamliel, A.; Yakobson, B.; Raz, T. Human-dog relationships during the COVID-19 pandemic: Booming dog adoption during social isolation. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2020, 7, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratschen, E.; Shoesmith, E.; Hawkins, R. Pets and the Pandemic: The Impact our Animals Had on Our Mental Health and Wellbeing. 2021. Available online: http://theconversation.com/pets-and-the-pandemic-the-impact-our-animals-had-on-our-mental-health-and-wellbeing-153393 (accessed on 7 December 2021).

- Wisdom, J.P.; Saedi, G.A.; Green, C.A. Another breed of “service” animals: STARS study findings about pet ownership and recovery from serious mental illness. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2009, 79, 430–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Levine, G.N.; Allen, K.; Braun, L.T.; Christian, H.E.; Friedmann, E.; Taubert, K.A.; Thomas, S.A.; Wells, D.L.; Lange, R.A. Pet ownership and cardiovascular risk: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2013, 127, 2353–2363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Müllersdorf, M.; Granström, F.; Sahlqvist, L.; Tillgren, P. Aspects of health, physical/leisure activities, work and socio-demographics associated with pet ownership in Sweden. Scand. J. Public Health 2010, 38, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chur-Hansen, A.; Stern, C.; Winefield, H. Commentary: Gaps in the evidence about companion animals and human health: Some suggestions for progress. Int. J. Evid.-Based Healthc. 2010, 8, 140–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pachana, N.A.; Ford, J.H.; Andrew, B.; Dobson, A.J. Relations between companion animals and self-reported health in older women: Cause, effect or artifact? Int. J. Behav. Med. 2005, 12, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Serpell, J. Beneficial effects of pet ownership on some aspects of human health and behaviour. J. R. Soc. Med. 1991, 84, 717–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Radloff, L.S. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 1977, 1, 385–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Survey Data; Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Atlanta, GA, USA. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/questionnaires/index.htm (accessed on 7 December 2021).

- NORC at the University of Chicago. GSS Data Explorer. Sponsored by National Science Foundation; NORC at the University of Chicago: Chicago, IL, USA. Available online: https://gssdataexplorer.norc.org/ (accessed on 7 December 2021).

- Applebaum, J.W.; Peek, C.W.; Zsembik, B.A. Examining U.S. pet ownership using the General Social Survey. Soc. Sci. J. 2020, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, R.S.; Jones, B.; Spicer, J.; Budge, R.C. Health correlates of compatibility and attachment in human-companion animal relationships. Soc. Anim. 2008, 6, 219–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimolag, U.; Krupa, T. Pet ownership as a meaningful community occupation for people with serious mental illness. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2009, 63, 126–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McConnell, A.R.; Brown, C.M.; Shoda, T.M.; Stayton, L.E.; Martin, C.E. Friends with benefits: On the positive consequences of pet ownership. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 101, 1239–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Black, K. The relationship between companion animals and loneliness among rural adolescents. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2012, 27, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stern, S.L.; Donahue, D.A.; Allison, S.; Hatch, J.P.; Lancaster, C.L.; Benson, T.A.; Johnson, A.L.; Jeffreys, M.D.; Pride, D.; Moreno, C.; et al. Potential benefits of canine companionship for military veterans with Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). Soc. Anim. 2013, 21, 568–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wright, H.; Hall, S.; Hames, A.; Hardiman, J.; Mills, R.; PAWS Project Team; Mills, D. Pet dogs improve family functioning and reduce anxiety in children with autism spectrum disorder. Anthrozoös 2015, 28, 611–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gadomski, A.M.; Scribani, M.B.; Krupa, N.; Jenkins, P.; Nagykaldi, Z.; Olson, A.L. Pet dogs and children’s health: Opportunities for chronic disease prevention? Prev. Chronic Dis. 2015, 12, 150204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lem, M.; Coe, J.B.; Haley, D.B.; Stone, E.; O’Grady, W. The protective association between pet ownership and depression among street-involved youth: A cross-sectional study. Anthrozoös 2016, 29, 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, S.S.; Wright, H.F.; Hames, A.; Mills, D.S. The long-term benefits of dog ownership in families with children with autism. J. Vet. Behav. 2016, 13, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsa-Sambola, F.; Williams, J.; Muldoon, J.; Lawrence, A.; Connor, M.; Currie, C. Quality of life and adolescents’ communication with their significant others (mother, father, and best friend): The mediating effect of attachment to pets. Attach. Hum. Dev. 2017, 19, 278–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Muldoon, A.L.; Kuhns, L.M.; Supple, J.; Jacobson, K.C.; Garofalo, R.; Dentato, M.; Cirulli, F. A web-based study of dog ownership and depression among people living with HIV. JMIR Ment. Health 2017, 4, e53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wu, C.S.T.; Wong, R.S.M.; Chu, W.H. The association of pet ownership and attachment with perceived stress among Chinese adults. Anthrozoös 2018, 31, 577–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, L.; Edwards, K.M.; McGreevy, P.; Bauman, A.; Podberscek, A.; Neilly, B.; Sherrington, C.; Stamatakis, E. Companion dog acquisition and mental well-being: A community-based three-arm controlled study. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carr, E.C.J.; Wallace, J.E.; Pater, R.; Gross, D.P. Evaluating the relationship between well-being and living with a dog for people with chronic low back pain: A feasibility study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Siegel, J.M. Stressful life events and use of physician services among the older adult: The moderating role of pet ownership. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1990, 58, 1081–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulick, E.E.; Krause-Parello, C.A. Factors related to type of companion pet owned by older women. J. Psychosoc. Nurs. Ment. Health Serv. 2012, 50, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fritz, C.L.; Farver, T.B.; Kass, P.H.; Hart, L.A. Association with companion animals and the expression of noncognitive symptoms in Alzheimer’s patients. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 1995, 183, 459–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cline, K.M. Psychological effects of dog ownership: Role strain, role enhancement, and depression. J. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 150, 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Ramírez, M.; Hernández, R. Benefits of dog ownership: Comparative study of equivalent samples. J. Vet. Behav. Clin. Appl. Res. 2014, 9, 311–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, P.; Trigg, J.; Godber, T.; Brown, C. An experience sampling approach to investigating associations between pet presence and indicators of psychological wellbeing and mood in older Australians. Anthrozoös 2015, 28, 403–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branson, S.; Boss, L.; Cron, S.; Turner, D. Depression, loneliness, and pet attachment in homebound older adult cat and dog owners. J. Mind Med. Sci. 2017, 4, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, M.K.; Gee, N.R.; Bures, R.M. Human-animal interaction as a social determinant of health: Descriptive findings from the health and retirement study. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, D.C.; Taylor, M.G.; Gee, N.R.; Sachs-Ericsson, N.J. Typologies of older adult companion animal owners and non-owners: Moving beyond the dichotomy. Aging Ment. Health 2019, 23, 1452–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Min, K.D.; Kim, W.H.; Cho, S.; Cho, S.I. Owners’ attitudes toward their companion dogs are associated with the owners’ depression symptoms—An exploratory study in South Korea. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Teo, J.; Thomas, S. Psychological mechanisms predicting wellbeing in pet owners: Rogers’ core conditions versus Bowlby’s attachment. Anthrozoös 2019, 32, 399–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endo, K.; Yamasaki, S.; Ando, S.; Kikusui, T.; Mogi, K.; Nagasawa, M.; Kamimura, I.; Ishihara, J.; Nakanishi, M.; Usami, S.; et al. Dog and cat ownership predicts adolescents’ mental well-being: A population-based longitudinal study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Parslow, R.A.; Jorm, A.F.; Christensen, H.; Rodgers, B.; Jacomb, P. Pet ownership and health in older adults: Findings from a survey of 2551 community-based Australians aged 60–64. Gerontology 2005, 51, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharpley, C.; Veronese, N.; Smith, L.; López-Sánchez, G.F.; Bitsika, V.; Demurtas, J.; Celotto, S.; Noventa, V.; Soysa, P.; Isik, A.T.; et al. Pet ownership and symptoms of depression: A prospective study of older adults. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 264, 35–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raina, P.; Waltner-Toews, D.; Bonnett, B.; Woodward, C.; Abernathy, T. Influence of companion animals on the physical and psychological health of older people: An analysis of a one-year longitudinal study. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 1999, 47, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Alayli, A.; Lystad, A.L.; Webb, S.R.; Hollingsworth, S.L.; Ciolli, J.L. Reigning cats and dogs: A pet-enhancement bias and its link to pet attachment, pet-self similarity, self-enhancement, and well-being. Basic Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2006, 28, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, D.L. Associations between pet ownership and self-reported health status in people suffering from chronic fatigue syndrome. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2009, 15, 407–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nagasawa, M.; Ohta, M. The influence of dog ownership in childhood on the sociality of elderly Japanese men. Anim. Sci. J. 2010, 81, 377–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rijken, M.; van Beek, S. About cats and dogs… Reconsidering the relationship between pet ownership and health related outcomes in community-dwelling elderly. Soc. Indic. Res. 2011, 102, 373–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enmarker, I.; Hellzén, O.; Ekker, K.; Berg, A.G. Depression in older cat and dog owners: The Nord-Trøndelag health study (HUNT)-3. Aging Ment. Health 2015, 19, 347–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, K.J.; Schreer, G. Pets and happiness: Examining the association between pet ownership and wellbeing. Anthrozoös 2016, 29, 283–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, J.; Parast, L.; Babey, S.; Griffin, B.A.; Saunders, J. A propensity-score-weighted population-based study of the health benefits of dogs and cats for children. Anthrozoös 2017, 30, 429–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batty, G.D.; Zaninotto, P.; Watt, R.G.; Bell, S. Associations of pet ownership with biomarkers of ageing: Population based cohort study. BMJ 2017, 359, j5558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dunn, S.; Sit, M.; DeVon, H.; Makidon, D.; Tintle, N. Dog ownership and dog walking: The relationship with exercise, depression, and hopelessness in patients with ischemic heart disease. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2017, 33, E7–E14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zijlema, W.; Christian, H.; Triguero-Mas, M.; Cirach, M.; van den Berg, M.; Maas, J.; Gidlow, C.J.; Kruize, H.; Wendel-Vos, W.; Andrušaitytė, S.; et al. Dog ownership, the natural outdoor environment and health: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e023000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branson, S.; Gee, N.; Padhye, N.; Boss, L. Biopsychosocial factors and cognitive function in cat ownership and attachment in community-dwelling older adults. Anthrozoös 2019, 32, 267–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| Original research | Review article/not original research |

| Pet ownership (dog/cat) | Animal assisted intervention or therapy |

| Assessment of pet ownership on some classification of mental health | Working/service animal |

| Accessible through library system | Pet ownership other than dog or cat |

| Quantitative data reported | Outcome only in animal |

| Written in English | Not accessible through library system |

| Only qualitative data reported | |

| Not written in English |

| Information Extracted from Articles |

|---|

| Study purpose |

| Type of research/Study design |

| Description of methods |

| Sample size |

| Demographics of sample |

| Type of pet (dog, cat, both) |

| How mental health diagnosis was obtained (self-report, scale, etc.) |

| Outcome variables |

| Mediating and moderating variables |

| Data analysis type |

| Main study findings |

| Type of impact on mental health (positive, mixed, none, negative) |

| Population Studied | Negative Impact | Mixed Impact | Positive Impact | No Impact | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Older adult | 2 | 7 | 5 | 14 (34%) | |

| Severely mentally ill | 1 | 2 | 3 (7%) | ||

| Children and adolescents | 1 | 4 | 1 | 6 (15%) | |

| General | 1 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 11 (27%) |

| Illness (cancer, back pain, etc.) | 1 | 2 | 2 | 5 (12%) | |

| Caregivers | 1 | 1 (2%) | |||

| Veterans | 1 | 1 (2%) | |||

| Totals | 3 (7%) | 15 (37%) | 12 (29%) | 11 (27%) | 41 |

| Population Studied | Negative Impact | Mixed Impact | Positive Impact | No Impact | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Older adult | 1 | 1 (8%) | |||

| Children and adolescents | 2 | 2 (15%) | |||

| General | 1 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 8 (61%) |

| Illness (cancer, back pain, etc.) | 1 | 1 (8%) | |||

| Adults living alone | 1 | 1 (8%) | |||

| Totals | 2 (15%) | 4 (31%) | 5 (38%) | 2 (15%) | 13 |

| Category of Mental Health | Measure Used |

|---|---|

| General mental health | General Mental Health Questionnaire (GHQ) (Versions 12; 30), Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI), Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF), Balanced Measure of Psychological Needs (BMPN), Patient Reported Outcomes (PROMIS), Mental Health Inventory (MHI), Colorado Symptom Inventory (CSI) |

| Well-being | Dimensions of Well-being (SPF-IL), Psychological Scale of Well-being (PWB), Psychological General Well-being Index (PGWB), Wisconsin Quality of Life Survey (W-QLI), Life Satisfaction Index Psychological Well-being for older adult (LSIA), Life Satisfaction Scale (SWLS), World Health Organization Five Well-being Index (WHO-5), Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT-G) |

| Loneliness | Lubben Social Isolation Scale for Older Adults (LNS-6), De Jong Gierveld Loneliness Scale, UCLA Loneliness Scale (ULS), UCLA Loneliness Revised (ULS-R) |

| Depression and anxiety | Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ), Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), Strait-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI-T), Screen for Child Anxiety Related Disorders (SCARED-5), Depression Anxiety Distress Scale (DASS), Kessler Psychological Distress (K-10), Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), Hospital Anxiety and Depression (HADS), Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI), Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale (SCAS), Geriatric Depression Scale Short Form (GDS-SF), Goldberg Anxiety and Depression Scale (GADS), Health Anxiety Inventory (HAI), Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (QIDS), PROMIS Depression, PROMIS Anxiety |

| Quality of life | Manchester Short Assessment of Quality of Life (MANSA), Health Related Quality of Life (HRQOL), KIDSCREEN-10, World Health Organization Quality of Life (WHOQOL-BREF), Short Form 36 Health Survey Questionnaire (SF-36) |

| Social support | Interpersonal support evaluation list (ISEL), Jichi Medical School Social Support Scale (JMS-SSS), Psychological Community Integration Scale (CIS-APP-34), Sarason Social Support Questionnaire (SSQSR), Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS), Brief Family Relationship Scale (BFRS), Barrett Lennard Relationship Inventory (BLRI), Networks for Support Scale (SSNS), PROMIS Companionship, PROMIS Emotional Support, Children’s Exposure to Domestic Violence Scale (CEDV), Social Provisions Scale (SPS), Multi-Dimensional Support Scale (MDSS) |

| Mood and self-regulation | Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS-SF), Emotional Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ), Modified Differential Emotions Scale (mDES) |

| Self-esteem, happiness, and life satisfaction | Subjective Fluctuating Happiness Scale (SFHS), Subjective Happiness Scale (SHS), Rosenberg Self Esteem Scale (RSES), Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS), Sense of Life Worth Living (IKIGAI), Happiness Index (HI), Life Satisfaction Index Z (LSI-Z), State Trait Hopelessness Scale (STHS) |

| Stress | Perceived Stress Scale (PSS), Parenting Stress Index (PSI-SF), Humor Stress Questionnaire (HSQ) |

| Other | Empathy Quotient Questionnaire (EQ), PTSD Checklist (PCL), Eysenck Personality Questionnaire-Revised (EPQ-R), Resilience Research Center Adult Resilience Measure (RRC-ARM), Child and Youth Resilience Measure (CRYM-28), Big Five Inventory (BFI), Personal Attributes Questionnaire (PAQ), Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ), Child Adolescent Bullying Scale (CABS), Alzheimer’s Caregiver Burden Interview (ZBI), Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ), Stress Salivary Biomarker |

| Attachment | Lexington Attachment to Pets Scale (LAPS), Short Attachment to Pets Scale (SAPS), Human Animal Bond (HAB), Owner-Pet Relationship Questionnaire (OPRQ), Pet Attachment Questionnaire (PAQ), Barrett-Lennard Relationship Inventory (BLR), CENSHARE Pet Attachment Survey (PAS) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Scoresby, K.J.; Strand, E.B.; Ng, Z.; Brown, K.C.; Stilz, C.R.; Strobel, K.; Barroso, C.S.; Souza, M. Pet Ownership and Quality of Life: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 332. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci8120332

Scoresby KJ, Strand EB, Ng Z, Brown KC, Stilz CR, Strobel K, Barroso CS, Souza M. Pet Ownership and Quality of Life: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Veterinary Sciences. 2021; 8(12):332. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci8120332

Chicago/Turabian StyleScoresby, Kristel J., Elizabeth B. Strand, Zenithson Ng, Kathleen C. Brown, Charles Robert Stilz, Kristen Strobel, Cristina S. Barroso, and Marcy Souza. 2021. "Pet Ownership and Quality of Life: A Systematic Review of the Literature" Veterinary Sciences 8, no. 12: 332. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci8120332

APA StyleScoresby, K. J., Strand, E. B., Ng, Z., Brown, K. C., Stilz, C. R., Strobel, K., Barroso, C. S., & Souza, M. (2021). Pet Ownership and Quality of Life: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Veterinary Sciences, 8(12), 332. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci8120332