Mural Endocarditis and Embolic Pneumonia Due to Trueperella pyogenes in an Adult Cow with Ventricular Septal Defect

Abstract

:1. Introduction

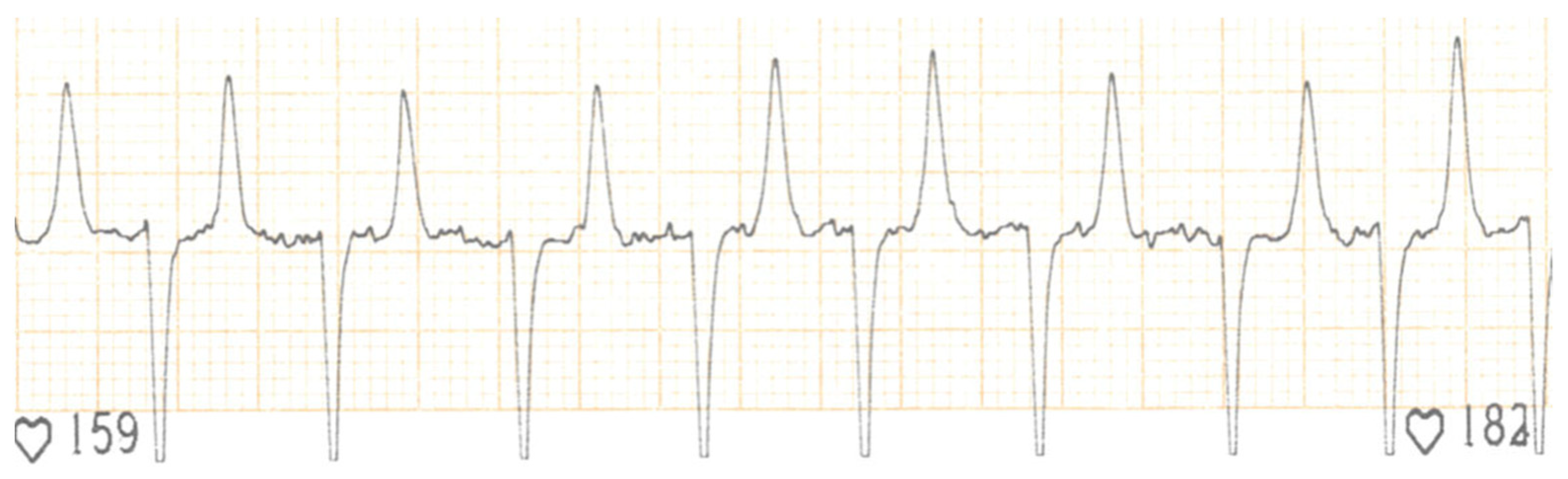

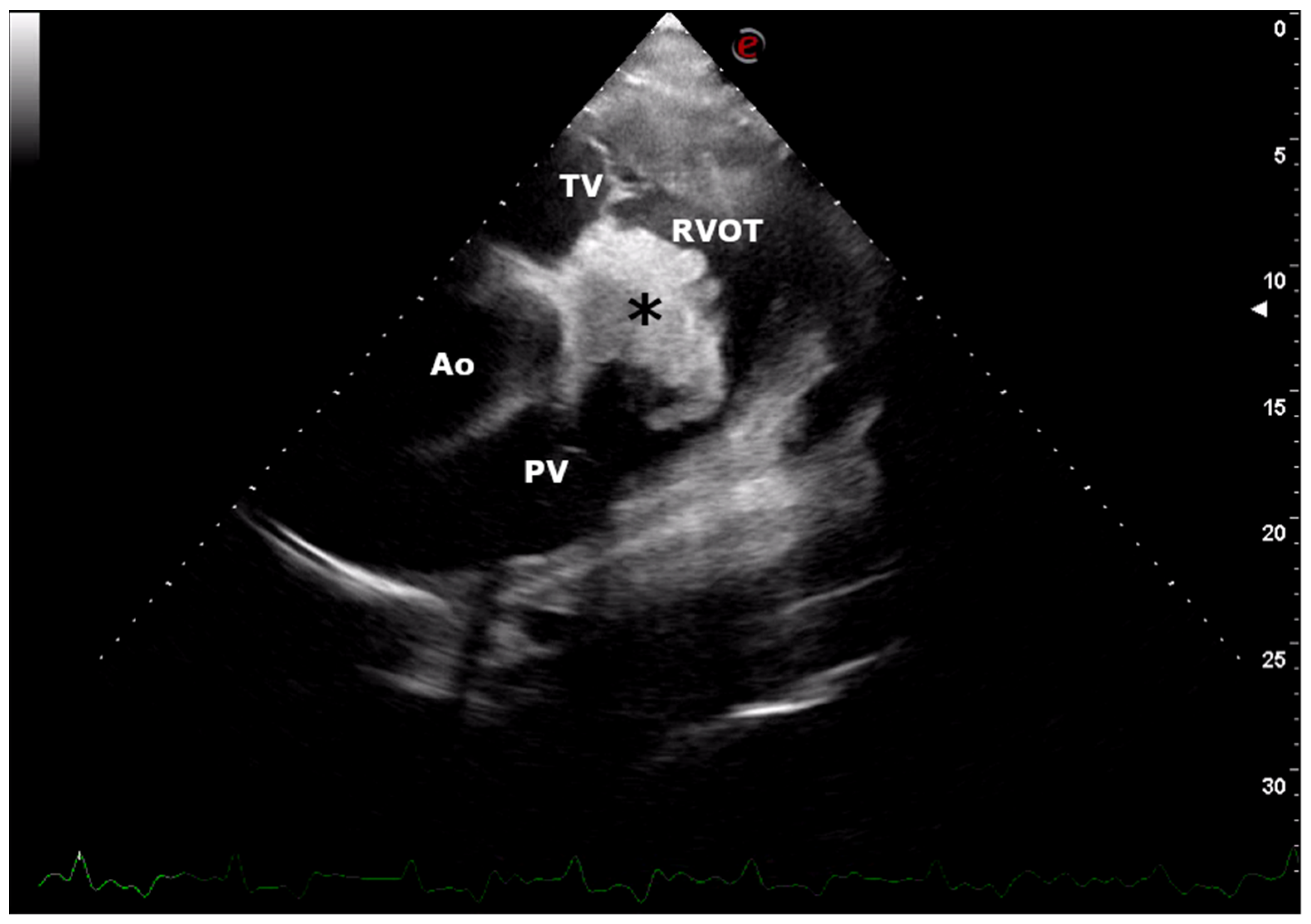

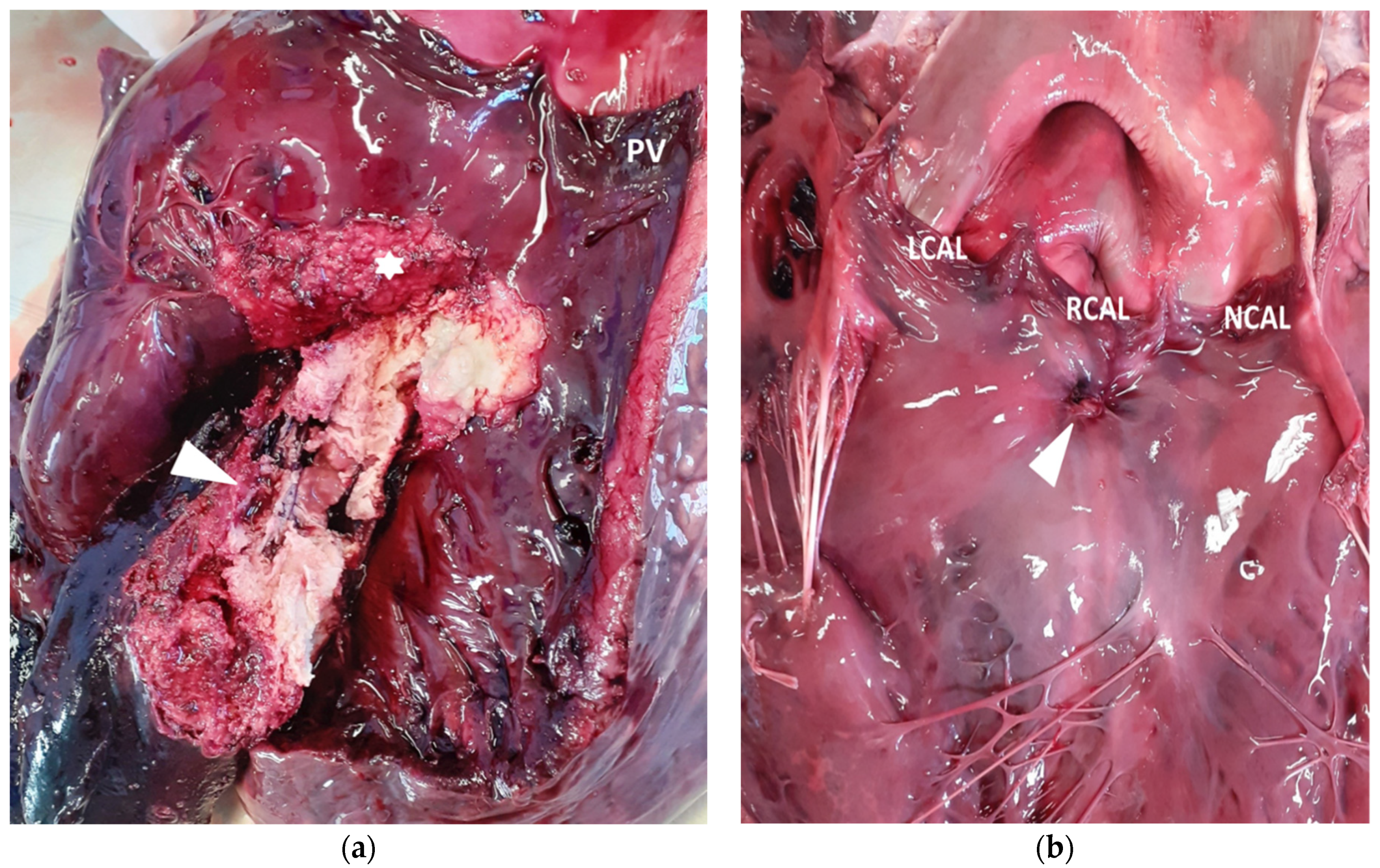

2. Case Presentation

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Andrews, A.H.; Williams, B.M. Bacterial conditions. In Bovine Medicine Diseases and Husbandry of Cattle, 2nd ed.; Andrews, A.H., Blowey, R.W., Boyd, H., Eddy, R.G., Eds.; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2004; pp. 726–782. [Google Scholar]

- Bexiga, R.; Mateus, A.; Philbey, A.W.; Ellis, K.; Barrett, D.C.; Mellor, D.J. Clinicopathological presentation of cardiac disease in cattle and its impact on decision making. Vet. Rec. 2008, 162, 575–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buczinski, S.; Francoz, D.; Fecteau, G.; Difruscia, R. A study of heart diseases without clinical signs of heart failure in 47 cattle. Can. Vet. J. 2010, 51, 1239–1246. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Buczinski, S.; Francoz, D.; Fecteau, G.; Difruscia, R. Heart disease in cattle with clinical signs of heart failure: 59 cases. Can. Vet. J. 2010, 51, 1123–1129. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Buczinski, S.; Rezakhani, A.; Boerboom, D. Heart disease in cattle: Diagnosis, therapeutic approaches and prognosis. Vet. J. 2010, 184, 258–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayer, A.S.; Scheld, W.M. Endocarditis and intravascular infections. In Mandell, Douglas and Bennett’s. In Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases, 5th ed.; Mandell, G.L., Bennett, J.E., Dolin, R., Eds.; Churchill Livingstone: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2000; pp. 857–902. [Google Scholar]

- Button, C. Conditions of the pericardium, myocardium, and endocardium. In Current Veterinary Therapy, Food Animal Practice, 2nd ed.; Howard, J.L., Ed.; Saunders: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1986; pp. 692–699. [Google Scholar]

- Cabana, E.M.; Kelly, W.R.; Daniel, R.C.; O’boyle, D. A case of bovine valvular endocarditis caused by Corynebacterium pseudodiphtheriticum. Vet. Rec. 1990, 126, 41–42. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Radostits, O.M.; Gay, C.C.; Blood, D.C.; Hinchcliff, K.W. Diseases of the cardiovascular system. In Veterinary Medicine. A Textbook of the Diseases of Cattle, Sheep, Pigs, Goats and Horses, 10th ed.; Radostits, O., Gay, C., Hinchcliff, K., Constable, P., Eds.; Elsevier Saunders: London, UK, 2007; pp. 399–438. [Google Scholar]

- Healy, A.M. Endocarditis in cattle: A review of 22 cases. Ir. Vet. J. 1996, 49, 43–48. [Google Scholar]

- Reef, V.B.; Mcguirk, S.M. Diseases of the cardiovascular system. In Large Animal Internal Medicine, 3rd ed.; Smith, B.P., Ed.; Mosby: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2002; pp. 443–478. [Google Scholar]

- Rezakhani, A.; Zarifi, M. Auscultatory findings of cardiac murmurs in clinically healthy cattle. Onl. J. Vet. Res. 2007, 11, 62–66. [Google Scholar]

- Werdan, K.; Dietz, S.; Löffler, B.; Niemann, S.; Bushnaq, H.; Silber, R.E.; Peters, G.; Müller-Werdan, U. Mechanisms of infective endocarditis: Pathogen-host interaction and risk states. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2014, 11, 35–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, H.M.; Heger, M.; Innerhofer, P.; Zehetgruber, M.; Mundigler, G.; Wimmer, M.; Maurer, G.; Baumgartner, H. Long-term outcome of patients with ventricular septal defect considered not to require surgical closure during childhood. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2002, 39, 1066–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Roehlich, W.F.; Wlaschitz, S.; Riedelberger, K.; Reef, V.B. Tricuspid valve endocarditis in a horse with a ventricular septal defect. Equine Vet. Educ. 2006, 18, 172–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, R.L.; Gordon, S.G.; Zhang, S.; Hariu, C.D.; Miller, M.W. Mural endocarditis caused by Corynebacterium mustelae in a dog with a VSD. J. Am. Anim. Hosp. Assoc. 2014, 50, 366–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherwin, V.; Baiker, K.; Wapenaar, W. Consequences of endocarditis in an adult cow with a ventricular septal defect. Vet. Rec. Case Rep. 2015, 3, e000234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Nie, C.J. Congenital malformations of the heart in cattle and swine. A survey of a collection. Acta Morphol. Neerl. Scand. 1966, 6, 387–393. [Google Scholar]

- Hagio, M.; Murakami, T.; Tateyama, S.; Otsuka, H.; Hamana, K.; Shimobepu, I. Congenital heart in disease in cattle. Bull. Fac. Agric. Miyazaki Univ. 1985, 32, 233–249. [Google Scholar]

- Gopal, T.; Leipold, H.W.; Dennis, S.M. Congenital cardiac defects in calves. Am. J. Vet. Res. 1986, 47, 1120–1121. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ohwada, K.; Murakami, T. Morphologies of 469 cases of congenital heart diseases in cattle. J. Jap. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2000, 53, 205–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- West, H.J. Congenital anomalies of the bovine heart. Br. Vet. J. 1988, 144, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandusky, G.E.; Smith, C.W. Congenital cardiac anomalies in calves. Vet. Rec. 1981, 108, 163–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caivano, D.; Marchesi, M.C.; Boni, P.; Venanzi, N.; Angeli, G.; Porciello, F.; Lepri, E. Double-Outlet Right Ventricle in a Chianina Calf. Animals 2021, 11, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buczinski, S.; Fecteau, G.; DiFruscia, R. Ventricular septal defects in cattle: A retrospective study of 25 cases. Can. Vet. J. 2006, 47, 246–252. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, K.J.; Schwarzwald, C.C. Echocardiography for the Assessment of Congenital Heart Defects in Calves. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Food Anim. Pract. 2016, 32, 37–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, K.; Uchida, E.; Schober, K.E.; Niehaus, A.; Rings, M.D.; Lakritz, J. Cardiac troponin I in calves with congenital heart disease. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2012, 26, 1056–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Post, K.W.; Rushton, S.D.; Billington, S.J. Valvular endocarditis associated with Helcococcus ovis infection in a bovine. J. Vet. Diagn. Invest. 2003, 15, 473–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Power, H.T.; Rebhun, W.C. Bacterial endocarditis in adult dairy cattle. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 1983, 182, 806–808. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Buczinski, S.; Tsuka, T.; Tharwat, M. The diagnostic criteria used in bovine bacterial endocarditis: A meta-analysis of 460 published cases from 1973 to 2011. Vet. J. 2012, 193, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brightling, P.; Townsend, H.G.G. Atrial fibrillation in ten cows. Can. Vet. J. 1983, 24, 331–334. [Google Scholar]

- Levy, M.; Deroth, L. Atrial fibrillation in cattle. Agri. Pract. 1983, 4, 25–33. [Google Scholar]

- Surborg, H. Elektrokardiographischer Beitrag zu den Herzrhythmusstörungen des Rindes. Dtsch. Tierärztl. Wochenschr. 1979, 86, 343–348. (In German) [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Caivano, D.; Marchesi, M.C.; Boni, P.; Passamonti, F.; Venanzi, N.; Lepri, E. Mural Endocarditis and Embolic Pneumonia Due to Trueperella pyogenes in an Adult Cow with Ventricular Septal Defect. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 318. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci8120318

Caivano D, Marchesi MC, Boni P, Passamonti F, Venanzi N, Lepri E. Mural Endocarditis and Embolic Pneumonia Due to Trueperella pyogenes in an Adult Cow with Ventricular Septal Defect. Veterinary Sciences. 2021; 8(12):318. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci8120318

Chicago/Turabian StyleCaivano, Domenico, Maria Chiara Marchesi, Piero Boni, Fabrizio Passamonti, Noemi Venanzi, and Elvio Lepri. 2021. "Mural Endocarditis and Embolic Pneumonia Due to Trueperella pyogenes in an Adult Cow with Ventricular Septal Defect" Veterinary Sciences 8, no. 12: 318. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci8120318

APA StyleCaivano, D., Marchesi, M. C., Boni, P., Passamonti, F., Venanzi, N., & Lepri, E. (2021). Mural Endocarditis and Embolic Pneumonia Due to Trueperella pyogenes in an Adult Cow with Ventricular Septal Defect. Veterinary Sciences, 8(12), 318. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci8120318